Difference between revisions of "Portico"

M-Westerby (talk | contribs) |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 311: | Line 311: | ||

Image:0739.jpg|William Russell Birch, “Landsdown,” before 1834. | Image:0739.jpg|William Russell Birch, “Landsdown,” before 1834. | ||

| − | File:0025.jpg|Robert P. Smith, “[[View]] of Washington,” c. 1850. | + | File:0025.jpg|Robert P. Smith, “''[[View]] of Washington'',” c. 1850. |

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Revision as of 13:25, July 9, 2020

History

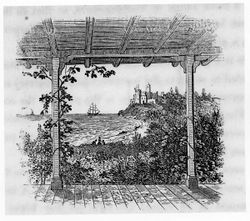

Portico is one of several words (including piazza, porch, and veranda) used to describe covered walks or spaces supported by columns or piers and attached to, or to part of, a building. This architectural feature spoke to the interrelatedness of architecture and gardens, a relationship that grew out of the romantic interest in landscape characterizing the aesthetics of the 18th and 19th centuries. Two images exemplify the importance of these structures in creating and framing views of the garden and landscape. The first is a drawing of York Island, Long Island, by William Russell Birch (1808), who explained that the view was taken from the piazza, a place from which one could see “innumerable seats, spreading over an extensive country which glittered as the sun arose” [Fig. 1].[1] The second is from A. J. Downing’s book on wooden picturesque houses, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850) [Fig. 2]. Both illustrate views from the bracketed piazza, or veranda, as Downing preferred to call it, out to the distant prospect.

Treatises often used these terms interchangeably, along with a few other less common words that were more or less synonymous. Downing and Alexander Jackson Davis used the term “umbrage” to refer to the same feature on a house, implying a place of shade; Downing used the term “pavilion” synonymously with “veranda”; and Mary Elizabeth Latrobe mentioned that in New Orleans the piazza was also known as the gallery.[2] Contrasting usage sometimes reveals distinctions. In his plan for a country house, Downing also used the term “porch” to identify the central area of the veranda leading to the entryway. The 19th-century architect William H. Ranlett sometimes distinguished between piazza and veranda, using “piazza” for a walk over which a projecting roof might be added, and “veranda” for a structure that included a roof (view text). Two points are important in the history of these terms: First, these architectural elements served to elide the boundaries of the garden and building by linking interior and exterior space both visually and physically. Second, the associative values of refinement and domesticity, and even national progress, were read into the forms.

The term “portico” was also used when referring to a covered space that was supported by columns or piers and was attached to a building. Semantic distinctions were made, however, using “portico” to identify the principal entrances to the house and “piazza” for the extended side porches. The higher status of the portico, as opposed to piazza, veranda, or porch, was emphasized by its frequent modification by adjectives such as “handsome,” “noble,” and “elegant.” The word “portico” seems not to have been used to refer to covered walkways that linked separate buildings, as is made clear in the distinction in 1777 regarding the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia (view text). Margaret Bayard Smith in 1828 said the portico at President James Madison’s plantation, Montpelier, commanded a view, “a beautiful scene,” of extensive lawns and forests, where viewers walked through the portico until twilight when the landscape was no longer visible (view text). John Mason recalled the portico at George Mason’s Gunston Hall, near Mason Neck, Virginia, from which “you descended directly into an extensive garden”(view text). Downing’s 1849 comments conveyed a similar meaning, suggesting that the portico served to connect the building, visually and also physically, “by gradual transition with the ground about it” ().

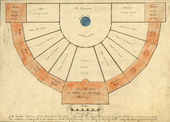

The portico served as a focal, as well as a viewing, point. Lewis Miller, for example, in 1849 wrote that at Mount Vernon the “lofty portico. . . has a pleasing effect when viewed from the water” (view text) [Fig. 3]. Often the portico was distinguished from the building it ornamented by its material, creating a distant focus for the spectator from the garden or surrounding landscape. A brick building was sometimes ornamented with a contrasting white stone or painted wood portico. As David Bailie Warden noted in 1816, such a feature made a house “admirably adapted to the American climate” (view text).

Porticoes generally were dressed in a classical style, meaning that classical columns supported the low-pitched roof and the front was finished with an entablature and pediment. Many descriptions specified Doric (e.g., Centre Square in Philadelphia), Tuscan (e.g., The Woodlands near Philadelphia), or Corinthian (e.g., Ranlett’s design for a house in Italian bracketed style). Two notable exceptions to the classical style, however, are well known. William Buckland’s fanciful octagonal porch at Gunston Hall (1755–58) had ogee arches and is thought to have been inspired by the writings of Batty Langley, who promoted Gothic and chinoiserie details for architectural decoration [Fig. 4]. Benjamin Henry Latrobe’s Gothic design for Sedgeley, near Philadelphia (1799) [Fig. 5], which is considered one of the earliest Gothic revival houses in America, had tall slender posts supporting the roof.

—Therese O’Malley

Texts

Usage

- Anonymous, 1737, describing in the St. Philip’s Parish Vestry Book St. Philip’s Parish, Charleston, SC (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 287)[3]

- “[Workmen recommended the constructions of] a large Cornish under ye eves & round ye Porticoes.”

- Carroll, Charles (the Barrister), July 2, 1767, describing Mount Clare, plantation of Charles and Margaret Tilghman Carroll, Baltimore, MD (quoted in Trostel 1981: 34)[4]

- “The Plan is for a Portico or Colonade to be Joined to the Front of a House and Project Eight Feet from it, An Arch at Both Ends, for a Passage through it, to Spring from Pilasters of Stone Joined to the End Pillars of the front of the Portico and the two three Quarter Round Columns, I think they Call them, that Run up Close to the wall of the House.”

- Anonymous, 1769, describing in the Georgia Gazette a proposed Presbyterian meetinghouse in Savannah, GA (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 287)[3]

- “[The meetinghouse was to be] 80 feet long by 47 feet wide. . . with a handsome light steeple in proportion to the frame, a portico at one end of 50 by 10 feet.”

- Fithian, Philip Vickers, March 18, 1774, describing Nomini Hall, Westmoreland County, VA (1943: 107)[5]

- “The North side [of Nomini Hall] I think is most beautiful of all; In the upper Story is a Row of seven Windows with eighteen Lights a piece; and below six windows, with the like number of lights; besides a large Portico in the middle, at the sides of which are two Windows each with eighteen Lights.”

- Hazard, Ebenezer, May 31, 1777, describing the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA (quoted in Shelley 1954: 405)[6]

- “The Wings are on the West Front, between them is a covered Parade, which reaches from the one to the other; the Portico is supported by Stone Pillars.” back up to History

- Clark, Jonathan, 1786, describing a farm in the Shenandoah Valley, VA (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 287)[3]

- “[There was a] fraimed dwelling house 26 by 20. . . and a portico the length of the fraimed house five feet wide.”

- Brissot de Warville, Jacques Pierre, 1792, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (quoted in Lockwood 1934: 2:61)[7]

- “I hastened to arrive at Mount Vernon. . . after having passed over two hills, you discover a country house of an elegant and majestic simplicity. . . This house overlooks the Potomack, enjoys an extensive prospect, has a vast and elegant portico on the front next to the river, and a convenient distribution of the apartments within.”

- Weld, Isaac, 1795, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1799: 2:207)[8]

- “In the center is another very spacious apartment, of an octagon form, reaching from the front to the rear of the house, the large folding glass doors of which, at each end, open under a portico.”

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, July 19 1796, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1977: 1:163)[9]

- “The House is connected with the Kitchen offices by arcades. . . Along the other front is a portico supported by 8 square pillars, of good proportions and effect.” [Fig. 6]

- Anonymous, 1803, describing in the Virginia Herald a property for rent in Fredericksburg, VA (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 286)[3]

- “. . . commodious close porch in front, and an open portico in the rear.”

- Anonymous, August 9, 1805, describing in the Virginia Herald a property for rent in Stafford County, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “FOR LEASE, A Lot of Land. . . On the above lot there is two convenient Dwelling houses, situate near each other, with two rooms on a floor and a portico to each, the whole length of the house, and convenient closets.”

- Scott, Joseph, 1806, describing Centre Square and Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (1806: 25)[10]

- “The water-works of Philadelphia are the most extensive of their kind of any in America. . . The water is discharged into a circular aqueduct, extending along Chestnut and Broad streets, into the middle of Market-street, in the centre square. . . The building in the centre square, is a square of sixty feet, with a Doric portico on the east and west fronts. From its centre rises a circular tower, forty feet in diameter. It is covered by a dome. The tower contains the engine and reservoir. . . large enough to contain 20,000 gallons, all the chimnies of the house, which form a marble pedestal, on the summit. The shafts of the columns of the porticos, consist each of one solid block of marble, 14 feet 9 inches in length, and two feet nine inches in diameter, at the base.”[Fig. 7]

- Drayton, Charles, November 2, 1806, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (Drayton 1806: 55)[11]

- “The walk is said to be a mile long—perhaps it is something less. One is led into the garden from the portico, to the east or lefthand.” [Fig. 8]

- Martin, William Dickinson, May 20, 1809, describing Philadelphia, PA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “The building in Centre Square, is Sixty feet in every direction; having a Doric portico in front, to the East & West.”

- Foster, Sir Augustus John, 1812, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1954: 144)[12]

- “The house has two porticoes of the Doric order, though one of them was not quite completed, and the pediment had in the meanwhile to be supported on the stems of four tulip trees, which are really, when well grown, as beautiful as the fluted shafts of Corinthian pillars. They front north and south.”

- Warden, David Bailie, 1816, describing Riversdale, estate of George and Rosalie Stier Calvert, Prince George’s County, MD (1816: 156)[13]

- “The establishment of George Calvert, Esq. at Bladensburg, attracts attention. His mansion, consisting of two stories, seventy feet in length, and thirty-six in breadth, is admirably adapted to the American climate. On each side there is a large portico, which shelters from the sun, rain, or snow.” back up to History

- Anonymous, September 30, 1820, describing in the Virginia Herald a property for rent in Culpeper County, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “I will sell my tavern establishment. . . consisting of. . . A large and commodious house with four rooms below stairs and eight above, with two large porticoes—a new smoke house, a new ice house.”

- Silliman, Benjamin, 1824, describing Monte Video, property of Daniel Wadsworth, Avon, CT (1824: 12)[14]

- “To the west, the lawn rises gradually from the water, until it reaches the portico of the house, near the brow of the mountain, beyond which, the western valley is again seen.”

- Ticknor, George, December 16, 1824, in a letter to William H. Prescott, describing Montpelier, plantation of James Madison, Montpelier Station, VA (quoted in Jones 1957: 7)[15]

- “We were received with a good deal of dignity and much cordiality, by Mr. and Mrs. Madison, in the portico, and immediately placed at ease.”

- Douglass, Frederick, 1825, describing Wye House, estate of Col. Edward Lloyd, Talbot County, MD (1855; repr., 1987: 47) [16]

- “The great house itself was a large, white, wooden building, with wings on three sides of it. In front, a large portico, extending the entire length of the building, and supported by a long range of columns, gave to the whole establishment an air of solemn grandeur.”

- Smith, Margaret Bayard, August 2, 1828, describing the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (1906: 226)[17]

- “The rotunda is in form and proportioned like the Pantheon at Rome. It has a noble portico,— the pillars, cornice, &c of the Corinthian.”

- Smith, Margaret Bayard, August 17, 1828, describing Montpelier, plantation of James Madison, Montpelier Station, VA (1906: 233, 235–36)[17]

- “We were at first conducted into the Drawing room, which opens on the back Portico and thus commands a view through the whole house, which is surrounded with an extensive lawn, as green as in spring; the lawn is enclosed with fine trees, chiefly forest, but interspersed with weeping willows and other ornamental trees, all of most luxuriant growth and vivid verdure. It was a beautiful scene! . . . After dinner, we all walked in the Portico, (or piazza, which is 60 feet long, supported on six lofty pillars) until twilight.” [Fig. 9] back up to History

- Anonymous, June 1829, describing Sedgeley, seat of James C. Fisher, near Philadelphia , PA (Casket 4: 265)[18]

- “The mansion was designed and erected under the superintendance of the late Mr. Latrobe, and has been much admired for its architectural beauty. The style is Gothic, with a portico front and rear, supported by eight columns each. It presents a length of seventy-five feet, and is well adapted in the arrangement of the interior for a gentleman’s residence.” [Fig. 10]

- Mason, General John, c. 1830, describing Gunston Hall, seat of George Mason, Mason Neck, VA (quoted in Rowland 1964: 1:98)[19]

- “The south front looked to the river; from an elevated little portico on this front you descended directly into an extensive garden, touching the house on one side.” back up to History

- Featherstonhaugh, George William, August 18 and 19 1837, describing Fort Hill, seat of John C. Calhoun, Clemson, SC (quoted in Jones 1957: 126)[15]

- “After partaking of an excellent dinner we adjourned for the evening to the portico, where with the aid of a guitar, accompanied by a pleasing voice, and some capital curds and cream, we prolonged a most agreeable conversazione until a late hour. . .

- “On our return to Fort Hill, the family again assembled in the portico to pass a most agreeable evening.”

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1842, describing Red Sulphur Springs, VA (Colonial Williamburg Foundation)

- “Behind the “Bachelor’s Row,” and on the upper part of the hill is an imposing edifice of brick, called “Society Hall.” It is built of two stories, with a fine portico of twelve feet wide, running the whole length of the front, and a terrace of twenty feet wide beyond this.”

- Anonymous, August 1848, describing Riversdale, estate of George and Rosalie Stier Calvert, Prince George’s County, MD (American Farmer 4: 53)[20]

- “The main building is 68 by about 50 feet, with an elegant Portico on its northern [front], and a Piaza [sic], running its entire length, on its southern front, each constructed with due regard to classic and architectural propriety.”

- Miller, Lewis, June 5, 1849, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (c. 1850: 108)[21]

- “The mansion house itself appears venerable and convenient[.] A lofty portico ninety-six feet in length, Supported by Eight pillars, has a pleasing effect when viewed from the water.” back up to History

Citations

- Dezallier d’Argenville, Antoine-Joseph, 1712, The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712; repr., 1969: 72)[22]

- “A PORTICO. . . being the Entrance in Front of a Summer-House, Salon, or Arbor of Latticework, and is generally adorn'd with a handsome Cornice and Frontispiece, supported by Pilasters or Peers; or else it is a long Decoration of Architecture placed against a Wall, or at the Entrance of a Wood, where the Advances and Returns are but inconsiderable.

- “ARBORS, Cabinets, and Porticos of Latticework, are commonly made use of to terminate a Garden in the City, and to shut out the Sight of Walls, and other disagreeable Objects; this Kind of Decoration making a handsome Sight, and serving very well to conclude the Prospect of a principal Walk.”

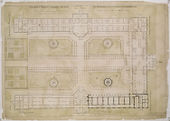

- Gibbs, James, 1728, A Book of Architecture (1728: n.p.)[23]

- “The Plan, Upright and Section of a Building of the Dorick Order in the form of a Temple, made for a Person of Quality, and proposed to have been placed in the Center of four Walks; so that a Portico might front each Walk.” [Fig. 11]

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1743, Cyclopaedia (1743: 2:n.p.)[24]

- “PIAZZA, in building, popularly called piache, an Italian name for a portico, or covered walk, supported by arches. See PORTICO.

- “The word literally signifies a broad open place or square; whence it also became applied to the walks or portico’s around them. . .

- “PORTICO, in architecture, a kind of gallery on the ground; or a piazza encompassed with arches supported by columns, where people walk under covert. See PIAZZA. . .

- “PORTICO. . .

- “The roof is usually vaulted, sometimes flat. The ancients called it lacunar. See LACUNAR, VAULT, &c.

- “Though the word portico be derived from porta, gate, door; yet it is applied to any disposition of columns which form a gallery, without any immediate relation to doors or gates.

- “The most celebrated portico’s of antiquity were those of Solomon’s temple, which formed the atrium or court, and encompassed the sanctuary: that of Athens, built for the people to divert themselves in, and wherein the philosophers held their disputes and conversations; which occasioned the disciples of Zeno to be called stoics. . . .

- “Among the modern portico’s, the most celebrated is the piazza of St. Peter of the Vatican.—That of Covent-Garden, London, the work of Inigo Jones, is also much admired.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 2:n.p.)[25]

- Ware, Isaac, 1756, Complete Body of Architecture (1756: 31)[26]

- “PORTICO.

- “A place for walking under shelter, raised with arches, in the manner of a gallery. The portico is usually vaulted, but it has sometimes a soffit, or ceiling. The portico is a piazza encompassed with arches raised upon columns, and covered over head in any manner. The word seems to refer to the gate or entrance of some place, porta in Latin signifying a gate; but it is appropriated to a disposition of columns, forming this kind of gallery, and has no relation to the openings.”

- Salmon, William, 1762, Palladio Londinensis (1762: n.p.)[27]

- “Piazza, in Architecture, commonly called Piache, an Italian Name for a Portico; it signifies a broad open Place or Square, whence it became applied to Walks or Porticos of Pillars around them, like those of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, &c.”

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (1789: n.p.)[28]

- Marshall, William, 1803, On Planting and Rural Ornament (1803: 1:266)[29]

- “IN extensive grounds, RETREATS, more especially in the remoter parts, are in a degree requisite; and, if they be seen, they ought to harmonize with the views in which they appear; and, of course, the more polished the scene, the more ornamental should be the Retreat,—whether it be the Room, the Portico, or the more simple Alcove.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[30]

- “PORTICO, n. [It. portico; L. porticus, from porta or portus.]

- “In architecture, a kind of gallery on the ground, or a piazza encompassed with arches supported by columns; a covered walk. The roof is sometimes flat; sometimes vaulted. Encyc.”

- Webster, Noah, 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1848: 848)[31]

- “POR'TI-CO, n. [It. portico; L. porticus, from porta or portus.]

- “In architecture, originally, a colonnade or covered ambulatory; but at present, a covered space, inclosed by columns at the entrance of a building. P. Cyc.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849: 376)[32]

- “In this country no architectural feature is more plainly expressive of purpose in our dwelling-houses than the veranda, or piazza. The unclouded splendor and fierce heat of our summer sun, render this very general appendage a source of real comfort and enjoyment; and the long veranda round many of our country residences stands instead of the paved terraces of the English mansions as the place for promenade; while during the warmer portions of the season, half of the days or evenings are there passed in the enjoyment of the cool breezes, secure under low roofs supported by the open colonnade, from the solar rays, or the dews of night. . .

- “The various projections and irregularities, caused by verandas, porticoes, etc., serve to connect the otherwise square masses of building, by gradual transition with the ground about it.” back up to History

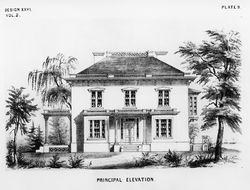

- Ranlett, William H., 1851, The Architect (1851; repr., 1976: 2:14)[33]

- “The design given in this part of the Architect, number XXVI., is the plan of a Villa in the Anglo-Italian style, now in process of erection on the south side of Lake Ontario, in the city of Oswego. . .

- “On the east side are two bay windows, one on each side of the principal entrance, which has a portico supported by fluted Corinthian columns. On the south is a flat-roofed piazza, with open balustrade railing, supported by Corinthian columns.” [Fig. 12] back up to History

Images

Inscribed

Michael van der Gucht, “Of Porticos, Bowers, and Cabinets of Arbor-work”, in Antoine-Joseph Dezallier d’Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712), pl. E opp. 71.

James Gibbs, “The Plan, Upright and Section of a Building of the Dorick Order in the form of a Temple,” in A Book of Architecture (1728), pl. 67.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Houses and a church. Garden plan with outbuildings, 1795–99. “Portico” is inscribed near the bottom of the plan.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, “View of Mount Vernon looking to the North,” July 17, 1796.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, “View of the East front of the President’s House, with the additions of the North & South Porticos,” 1807.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, “General Plan of a Marine Asylum and Hospital proposed to be built at Washington,” 1812. “Portico” is inscribed at the Western entrance.

Robert Mills, Plan of wings and courtyards, South Carolina Insane Asylum, 1821, in John M. Bryan, ed., Robert Mills, Architect (1989), pl. 10. “Portico” is inscribed near the bottom of the plan.

J. C. Loudon, “Porches and Porticoes,” in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 356, fig. 330.

Lewis Miller, “Mount Vernon” [detail], in Orbis Pictus (c. 1849), 108.

Associated

Thomas Jefferson, Monticello: 1st version (elevation), probably before March 1771.

James Peller Malcolm, The Woodlands From the Bridge at Gray’s Ferry, c. 1792, in Beth C. Wees and Medill H. Harvey, Early American Silver in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (2013), 259.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, “View of Mount Vernon looking towards the South,” 1796.

Francis Guy, Mount Deposit from the North, 1805.

William Strickland, “The Woodlands,” 1809, in Casket 5, no. 10 (October 1830): pl. opp. 432.

John Lewis Krimmel, Fourth of July in Centre Square, 1811–12.

Robert Mills, Front elevation, South Carolina Insane Asylum, c. 1820, in John M. Bryan, ed. Robert Mills, Architect (1989), pl. 7.

Jane Braddick, View of West Front of Monticello and Garden, 1825.

Victor De Grailly, Mount Vernon, c. 1840—50.

Frances Palmer, “Italian Bracketed Villa,” in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), vol. 2, pl. 7.

Frances Palmer, East Front Elevation of Italian Bracketed Villa, in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), vol. 2, pl. 9, top.

Attributed

Charles Willson Peale, Charles Carroll, c. 1770.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Houses and a church. Garden temple elevations and floor plan, c. 1795–99.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Houses and a church. Side elevation and basement floor plan, c. 1795–99.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Houses and a church. Lodge—Sections showing interior elevation, c. 1795–99.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Sedgeley, 1799.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, “Elevation of the South front of the President’s house, copied from the design as proposed to be altered in 1807,” January 1817.

Mdme. Janika de Feriet, The Hermitage, c. 1820.

Robert P. Smith, “View of Washington,” c. 1850.

Notes

- ↑ William Russell Birch, The Country Seats of the United States of North America: With Some Scenes Connected with Them (Springland, PA: W. Birch, 1808), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Pierson Jr. traces the origins of the feature, specifically found in Alexander Jackson Davis and A. J. Downing’s work, to the awning or canopy partaking of an oriental flavor. In general, its origin was a semi-enclosed outdoor space that was not at all architectural but was related to the ornamental canopy or tent. This connection might explain why the detail flourished during the high romantic period in American architecture. See Pierson, American Buildings and Their Architects: Technology and the Picturesque, the Corporate and the Early Gothic Styles, 2 vols. (New York: Doubleday, 1978), 2:300–4, view on Zotero. Also see Alexander Jackson Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses; Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-Houses, and Villas (1850; repr., New York: D. Appleton; Da Capo, 1968), 357, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Michael Trostel, Mount Clare, Being an Account of the Seat Built by Charles Carroll, Barrister, upon His Lands at Patapsco (Baltimore: National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the State of Maryland, 1981), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Philip Vickers Fithian, Journal & Letters of Philip Vickers Fithian, 1773–1774: A Plantation Tutor of the Old Dominion, ed. Hunter D. Farish (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg, 1943), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fred Shelley, “The Journal of Ebenezer Hazard in Virginia, 1777,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 62 (1954): 400–23, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alice B. Lockwood, ed., Gardens of Colony and State: Gardens and Gardeners of the American Colonies and of the Republic before 1840, 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s for the Garden Club of America, 1931–34), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Isaac Weld, Travels through the States of North America and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, during the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797, 2 vols. (London: John Stockdale, 1799), on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Henry Latrobe, The Virginia Journals of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1795-1798, ed. Edward C. Carter II, 2 vols. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph A. Scott, Geographical Description of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Printed by R. Cochran, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Drayton, “The Diary of Charles Drayton I, 1806,” Drayton Hall: A National Historic Trust Site, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sir Augustus John Foster, Jeffersonian America: Notes on the United States of America Collected in the Years 1805–1806–1807 and 1811–1812, ed. Richard Beale Davis (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1954) view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Bailie Warden, A Chronographical and Statistical Description of the District of Columbia (Paris: Printed and sold by Smith, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Silliman, Remarks Made on a Short Tour between Hartford and Quebec, in the Autumn of 1819 (New Haven, CT: S. Converse, 1824), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Katharine M. Jones, The Plantation South (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1957), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom, ed. William L. Andrews (1855; repr., Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, ed. Gaillard Hunt (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1906), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Sedgeley Park, the Seat of James C. Fisher, Esq.,” Casket, or Flowers of Literature, Wit & Sentiment 4, no. 6 (June 1829): 265, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kate Mason Rowland, The Life of George Mason: 1725–1792, 2 vols. (New York: Russell and Russell, 1964), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Visit to Riversdale,” American Farmer, and Spirit of Agricultural Journals of the Day 4, no. 2 (August 1848): 52–55, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lewis Miller, Orbis Pictus: A Picturesque Album to the Ladies of York, Pennsylvania (Williamsburg, VA: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, c. 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A.-J. (Antoine Joseph) Dézallier d’Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening. . . , trans. John James (London: Geo. James, 1712; repr., Farnborough, England: Gregg, 1969), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Gibbs, A Book of Architecture, Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments, (London: Printed for W. Innys et al., 1728), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741–43), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, Samuel, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Isaac Ware, A Complete Body of Architecture (London: T. Osborne and J. Shipton, 1756), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Salmon, Palladio Londinensis, or The London Art of Building: In Three Parts. . . with Fifty-Four Copper Plates, to Which Is Annexed, The Builder’s Dictionary, ed. E. Hoppus, 6th ed. (London: Printed for C. Hitch et al., 1762), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas A. Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews. . . , 5th ed. (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Marshall, On Planting and Rural Ornament: A Practical Treatise . . ., 2 vols. (London: G. and W. Nicol, G. and J. Robinson, T. Cadell, and W. Davies, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged by Chauncey A. Goodrich, (Springfield, MA: George and Charles Merriam, 1848), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Jackson Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America. . ., 4th ed. (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William H. Ranlett, The Architect, 2 vols. (1849–51; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1976), view on Zotero.