Difference between revisions of "Seat"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 118: | Line 118: | ||

| − | *Scott, Joseph, 1806, describing the Schuylkill River in Pennsylvania (1806: 53)<ref>Joseph Scott, ''A Geographical Description of Pennsylvania'' (Philadelphia: Printed by R. Cochran, 1806). [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/55XKIWPN/].</ref> | + | *Scott, Joseph, 1806, describing the Schuylkill River in Pennsylvania (1806: 53)<ref>Joseph Scott, ''A Geographical Description of Pennsylvania'' (Philadelphia: Printed by R. Cochran, 1806). [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/55XKIWPN/ view on Zotero].</ref> |

:“The banks of the river are, in many places, adorned with beautiful country '''seats''', belonging to the wealthy citizens of Philadelphia. To these their families usually retire, in the summer months, from the bustle, and noise of the city, and to enjoy the salubrity of the country air.” | :“The banks of the river are, in many places, adorned with beautiful country '''seats''', belonging to the wealthy citizens of Philadelphia. To these their families usually retire, in the summer months, from the bustle, and noise of the city, and to enjoy the salubrity of the country air.” | ||

Revision as of 20:56, January 23, 2020

History

In the discourse of landscape design, seat possessed two distinct yet equally prevalent meanings, as indicated by Thomas Sheridan’s 1789 dictionary entry. One sense referred to seat as a large estate, usually marked by a country house or mansion, for example, William Hamilton’s The Woodlands, near Philadelphia; or General Charles Ridgely’s Hampton, in Baltimore County, Maryland. A seat was also a garden structure for sitting.

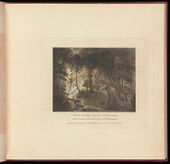

The meaning of seat as estate was exemplified in colonial America by William Byrd II’s Westover, on the James River, Virginia, and Henry Pratt’s Lemon Hill in Philadelphia. Such country houses were often featured in portraits that flattered the owner and signaled to the public that the colonies and new republic were home to a cultured elite rivaling that of Great Britain. These images typically located the house at the center of the property, with the landscape and various outbuildings extending beyond it. This placement, which communicated the importance of the house as the base of operations for the landowner, was a visual shorthand for the landowner’s affluence and power. Observers such as William Hugh Grove (1732) and Thomas Gwatkin (1770) often likened seats to small villages. By the mid 18th century, however, the community-like aspects of seats were downplayed in favor of their rural associations, which contrasted sharply with the increasingly crowded conditions of America’s cities. English emigré William Russell Birch, in his series The Country Seats of the United States of America (1808), depicted the homes of the mid-Atlantic elite situated in naturalistic landscapes in emulation of British tableaux [Fig. 1].[1]

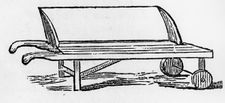

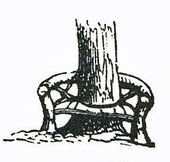

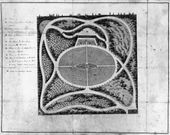

As a category of garden furniture, seat could refer to either the object upon which one sat [Fig. 2] or the structure housing such objects [Fig. 3]. Accounts found in foreign treatises available in America (such as those by Antoine-Joseph Dezallier D’Argenville, Isaac Ware, William Marshall, Humphry Repton, and John Abercrombie) focused on seats as places of rest, terminations to walks, or vantage points from which to contemplate views. Like other garden structures, such as pavilions or summerhouses, seats influenced the viewer’s experience of the garden by providing points of rest that framed vistas in the garden and views beyond. The use of seats to direct one’s route through a garden was demonstrated by A. J. Downing in his 1847 description of Montgomery Place, Dutchess County, New York. Downing noted the placement of various seats and related views that he encountered on the course of his walk through the grounds. Many other garden observers, including Henry Wansey (1794), John Cosens Ogden (1800), and Eliza Caroline Burgwin Clitherall (active 1801), also commented upon the interrelationships between seats, walks, and views. Popular gardening journals likewise recommended placing seats along walks. For example, in 1841 Alexander Walsh proposed a number of seats in a garden design published in the New England Farmer. Two seats were situated at cross-walks and another two were ensconced in an arched arbor, placed alongside the main axial walk.

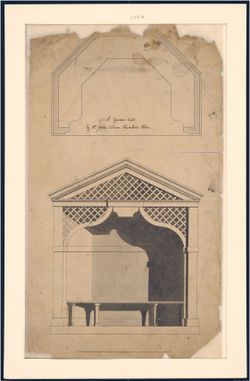

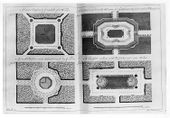

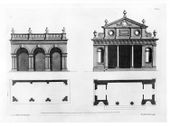

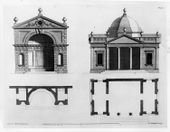

Garden seats took on a variety of forms. In the 18th century, European and British pattern books and design manuals such as James Gibbs’s A Book of Architecture (1728) were an important source for American seat designs [Fig. 4]. Drawings by Thomas Jefferson and by his granddaughter, Cornelia Jefferson Randolph [Fig. 5], demonstrate the influence of William Kent’s designs on garden furniture, which appeared in William Chambers’s Plans, Elevations, Sections and Perspective Views of the Gardens and Buildings at Kew in Surrey (1763), a volume that Jefferson owned.[2]

Seat designs could be differentiated by national and historical styles, as well as by placement and function. Batty and Thomas Langley, for instance, proposed a seat in keeping with the Gothic style in their 1747 text about Gothic architecture [Fig. 6]. J. C. Loudon, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), distinguished among seats found inside garden buildings, roofed seats that could be either fixed or portable, and those lacking any sort of roof. Loudon explained that in form, seats could be simple (like the trunk of a tree) or more complex (such as a cast-iron couch with decorative treatment). These distinctions were echoed by Jane Loudon in Gardening for Ladies (1845), a book that was co-edited by Downing in America.

In A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), Downing himself provided an extensive illustrated typology of seat styles, emphasizing the propriety of certain styles for different landscapes. For example, he believed that Grecian or Gothic seats were appropriate for elegant grounds, whereas rustic seats were more suited to the irregular aesthetic of the landscape garden. Such rustic seats were quite popular in the 19th century, as suggested by the discussion of them in horticultural journals, such as the Horticultural Register, and in descriptions by both treatise writers and observers of the American landscape. See, for example, Thomas Bridgeman (1832), Edward Sayers (1838), Anna Cora Ogden Mowatt Ritchie (1839), C. M. Hovey (1840), and Georges Jaques (1852).

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Anonymous, n.d., advertising design and construction services for parks and gardens (quoted in Chase 1973: 37–39)[3]

- “Designs all sorts of Buildings, well suited to both town and country, Pavilions, Summer-Rooms, Seats for Gardens. . . also Water-houses for Parks. . . Eye Traps to represent a Building terminating a walk, or to hide some disagreeable Object, Rotundas, Colonades, Arcades, Studies in Parks or Gardens, Green Houses for the Preservation of Herbs.”

- Strachey, William, 1612, describing the seats of Powhatan in Virginia (quoted in Wright and Freund 1967: 57)[4]

- “He hath divers seates or howses, his Chief when we came into the Country was upon Pamunky-River, on the North side which we call Pembrook-side, called Werowocomaco, which by interpretacion signifyes Kings-howse.”

- Byrd, William, II, c. June 25, 1729, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd II, on the James River, VA (quoted in Tinling 1977: 1:410)[5]

- “My habitation has the na[me of] the prettyest seat in this country.”

- Grove, William Hugh, 1732, describing Williamsburg, VA (quoted in Stiverson and Butler 1977: 26)[6]

- “I went by ship up the [York] river, which has pleasant Seats on the Bank which Shew Like little villages, for having Kitchins, Dayry houses, Barns, Stables, Store houses, and some of them 2 or 3 Negro Quarters all Seperate from Each other but near the mansion houses make a shew to the river of 7 or 8 distinct Tenements, tho all belong to one family.”

- Anonymous, August 17, 1747, describing property for sale in Somerset County, NJ (New York Gazette)

- “TO BE SOLD, A pleasant Country Seat, fitting for a Gentleman or Store-keeper. . . a good Orchard, containing about 200 Apple Trees, and may be extended at Pleasure.”

- Gwatkin, Prof. Thomas, 1770, describing the appearance of seats in Williamsburg, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “And the huts of the Negroes which are situated round about give the seat of a substantial planter something of the Air of a small village.”

- Rush, Dr. Benjamin, July 15, 1782, describing the country seat of John Dickinsen, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 87)[7]

- “The ground contiguous to this shed was cut into beautiful walks and divided with cedar and pine branches into artificial groves. The whole, both the buildings and walks, were accommodated with seats.”

- Shippen, Thomas Lee, December 31, 1783, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd III, on the James River, VA (1952: n.p.)[8]

- “I have markd some little crooked ugly figures for Gentlemen’s seats, which tho’ they do not beautify indeed the picture, add much to the prospect, about as many Seats are to be seen on the other side.” [Fig. 7]

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 13, 1787, describing The Hills (later Lemon Hill), estate of Robert Morris, Philadelphia, PA (1987: 1:256–57)[9]

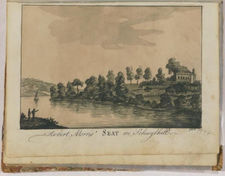

- “We continued our route, in view of the Schuylkill, and up the river several miles, and took a view of a number of Country-seats, one belonging to Mr. R. Morris, the American financier, and who is said to be possessed of the greatest fortune in America. His country-seat is not yet completed, but it will be superb. It is planned on a large scale, the gardens and walks are extensive, and the villa, situated on an eminence, has a commanding prospect down the Schuylkill to the Delaware.” [Fig. 8]

- G., L., June 15, [1788?], describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Madsen 1989: 19)[10]

- “[The walks were] planted on each side with the most beautiful & curious flowers & shrubs. They are in some parts enclosed with the Lombardy poplar except here & there openings are left to give you a view of some fine trees or beautiful prospect beyond, & in others, shaded by arbours of the wild grape, or clumps of large trees under which are placed seats where you may rest yourself & enjoy the cool air.”

- Constantia [Judith Sargent Murray], June 24, 1790, “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania” (Massachusetts Magazine 3: 415)[11]

- “At every turn shaded seats are artfully contrived, and the ground abounds with arbours, alcoves, and summer houses, which are handsomely adorned with odoriferous flowers.”

- L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, 1791, describing Washington, DC (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 136, 151)[7]

- “[March 11, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson]. . . The remainder part of that ground towards Georgetown is more broken. It may afford pleasant seats, but, although the bank of the river between the two creeks can command as grand a prospect as any of the other spots, it seems to be less commendable for the establishment of a city, not only because the level surface it presents is but small, but because the hights from beyond Georgetown absolutely command the whole. . .

- “[June 22, in a report to George Washington]. . . I next made the distribution regular with streets at right angle north-south and east west but afterwards I opened others on various directions as avenues to and from every principal places, wishing by this not merely to contrast with the general regularity nor to afford a greater variety of pleasant seats and prospect as will be obtained from the advantageous ground over the which the avenues are mostly directed but principally to connect each part of the city with more efficacy.”

- Wansey, Henry, 1794, describing Worcester, MA (1794; repr., 1970: 64)[12]

- “Most of the houses have a large court before them, full of lilacs and other shrubs, with a seat under them, and a paved walk up the middle.”

- Blandulus [pseud.], November 1794, describing Pleasant Hill, seat of Joseph Barrell, Charlestown, MA (quoted in Hammond 1982: 95)[13]

- “Whereonce the breastwork mark’d the scenes of

- blood,

- While Freedom’s sons inclosed the haughty foe,

- Rearing its head majestic from afar

- The venerable seat of Barrell stands

- Like some strong English Castle.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing mill seats in Massachusetts (1821: 2:352)[14]

- “Immediately below the bridge [over Miller’s River] is a fall, furnishing excellent mill-seats, which are occupied by several mills. These are uniformly supplied with an abundance of water, and wear the aspect of great activity, and business, particularly in the sawing of timber.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1799, describing New York, NY (1822: 3:481–82)[14]

- “the heights, and many of the lower grounds, contain a rich display of gentlemen’s country seats, connected with a great variety of handsome appendages.”

- La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, François-Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de, 1799, describing a house in Charleston, SC (1800: 2:437–38)[15]

- “Half a mile from Batavia. . . stands Middletonhouse, the property of Mrs. MIDDLETON, mother-in-law to young Mr. Isard, which is esteemed the most beautiful house in this part of the country. The out-buildings, such as kitchen, wash-house, and offices, are very capacious. The ensemble of these buildings calls to recollection the ancient English country-seats.”

- La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, François-Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de, 1799, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Madsen 1988: B3)[16]

- “You pass the Schuylkill at Gray’s-Ferry, the road to which runs below Woodlands, the seat of Mr. William Hamilton: it stands high, and is seen upon an eminence from the opposite side of the river.” [Fig. 9]

- Ogden, John Cosens, 1800, describing Bethlehem, PA (1800: 18, 27)[17]

- “Seats are placed for rest, and to enable the visitors to view the river at leisure. . .

- “The island is not large, but affords fine walks and an area for exercise, as well as seats and shelters for visitors.”

- Clitherall, Eliza Caroline Burgwin (Caroline Elizabeth Burgwin), active 1801, describing the Hermitage, seat of John Burgwin, Wilmington, NC (quoted in Flowers 1983: 126)[18]

- “These [gardens] were extensive and beautifully laid out. There was [sic] alcoves and summer houses at the termination of each walk, seats under trees in the more shady recesses of the Big Garden, as it was called, in distinction from the flower garden in front of the house.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1804, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (Massachusetts Historical Society, Jefferson Papers)

- “Temples or seats at those spots on the walks most interesting either for prospect or the immediate scenery.”

- Scott, Joseph, 1806, describing the Schuylkill River in Pennsylvania (1806: 53)[19]

- “The banks of the river are, in many places, adorned with beautiful country seats, belonging to the wealthy citizens of Philadelphia. To these their families usually retire, in the summer months, from the bustle, and noise of the city, and to enjoy the salubrity of the country air.”

- Martin, William Dickinson, 1809, describing the pleasure grounds at Salem Academy, Salem, NC (quoted in Bynum 1979: 29)[20]

- “Next, I visited a flower garden belonging to the female department. . . But it is situated on a hill, the East end of which is high & abrupt; some distance down this, they had dug down right in the earth, & drawing the dirt forward threw it on rock, etc., thereby forming a horizontal plane of about thirty feet in circumference; & on the back, rose a perpendicular terrace of some height, which was entirely covered over with a grass peculiar to that vicinage. At the bottom of this terrace were arranged circular seats, which, from the height of the hill in the rear were protected from the sun in an early hour in the afternoon.”

- Martin, William Dickinson, May 20, 1809, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Altho’ much has been done to beautify this delightful seat, much still remains to be done, for the perfecting it in all the capabilities which nature in her boundless profusion has bestowed.”

- Smith, Margaret Bayard, August 1, 1809, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1906: 73)[21]

- “Mr. J. explained to me all his plans for improvement, where the roads, the walks, the seats, the little temples were to be placed.”

- Foster, Sir Augustus John, 1812, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1954: 143)[22]

- “It is a very delightful ride of twenty-eight miles from Montpellier to the late President Mr. Jefferson’s seat at Monticello.”

- Lambert, John, 1816, describing Boston, MA (1816: 2:328)[23]

- “From an elevated part of the town the spectator enjoys a succession of the most beautiful views that imagination can conceive. Around him, as far as the eye can reach, are to be seen towns, villages, country seats, rich farms, and pleasure-grounds, seated upon the summits of small hills, hanging on the brows of gentle slopes, or reclining in the laps of spacious valleys, whose shores are watered by a beautiful river, across which are thrown several bridges and causeways.”

- Randolph, John, 1820s, describing an estate in Roanoke, VA (quoted in Martin 1991: 223n. 46)[24]

- “From my earliest childhood I have delighted in the groves and solitudes of poor old Matoax. I now recall several of my favorite seats where I used to ruminate, ‘chewing the cud of sweet and bitter fancies,’ all bitter now.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:381)[25]

- “He wanted a place to keep the garden seeds & Tools, and in a part of the Garden where a seat in the shade was often wanted, he built a shed or small room, and to hide that Salt-like-box, and to try his art of Painting, he made the front like [a] Gate Way with a step to form a seat, and above, steps painted as representing a passage through an Arch beyond which was represented a western sky, and to ornament the upper part over the arch, he painted several figures on boards cut to the outlines of said figures as representing statues in sculpture.”

- Sheldon, John P., December 10, 1825, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Gibson 1988: 5)[26]

- “Delightful seats, surrounded by various kinds of trees and shrubbery, with gardens containing summer houses, vistas, embowered walks, &c meet your view in almost every direction, woods sloping gently to the river’s edge, by the side of smooth lawns, add to the pleasing variety of the scene; and the Schuylkill, with its noble dam and bridges serves as a most beautiful finish to the foreground.” [Fig. 10]

- Connor, Juliana Margaret, 1827, describing the garden at the pottery (Lot 48) on Main Street, Salem, NC (quoted in Bynum 1979: 28)[20]

- “Afterwards walked into the garden belonging to the establishment where we saw what I conceived to be a curiosity and in itself extremely beautiful. It was a large summer house formed of eight cedar trees planted in a circle, the tops whilst young were chained together in the center forming a cone. The immense branches were all cut, so that there was not a leaf, the outside is beautifully trimmed perfectly even and very thick within, were seats placed around and doors or openings were cut, through the branches, it had been planted 40 years.”

- Bernhard, Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, 1828, describing the Bloomingdale Asylum for the Insane, New York, NY (quoted in Little 1972: 64)[27]

- “The Lunatic Asylum is five miles from the city [New York] on a hill, in a very healthy situation, the road leads between country seats and handsome gardens and is one of the most pleasant I have seen in America.”

- Wailes, Benjamin L. C., December 29, 1829, describing Lemon Hill, estate of Henry Pratt, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Moore 1954: 359)[28]

- “But the most enchanting prospect is towards the grand pleasure grove & green house of a Mr. Prat[t], a gentleman of fortune, and to this we next proceeded by a circutous [sic] rout, passing in view of the fish ponds, bowers, rustic retreats, summer houses, fountains, grotto, &c., &c. The grotto is dug in a bank [and] is of a circular form, the side built up of rock and arched over head, and a number of Shells [?]. A dog of natural size carved out of marble sits just within the entrance, the guardian of the place. A narrow aperture lined with a hedge of arbor vitae leads to it. Next is a round fish pond with a small fountain playing in the pond. An Oval & several oblong fish ponds of larger size follow, & between the two last is an artificial cascade. Several summer houses in rustic style are made by nailing bark on the outside & thaching the roof. There is also a rustic seat built in the branches of a tree, & to which a flight of steps ascend. In one of the summer houses is a Spring with seats arrond it. The houses are all embelished [sic] with marble busts of Venus, Appollo, Diana and a Bacanti. One sits on an Island on the fish pond. All the ponds filled with handsome coloured fish.”

- Trollope, Frances Milton, 1830, describing Philadelphia, PA (1832: 2:48–49; 152)[29]

- “Near this enclosure [at the State House] is another of much the same description, called Washington Square. Here there was an excellent crop of clover; but as the trees are numerous, and highly beautiful, and several commodious seats are placed beneath their shade, it is, spite of the long grass, a very agreeable retreat from heat and dust. It was rarely, however, that I saw any of these seats occupied; the Americans have either no leisure, or no inclination for those moments of delassement that all other people, I believe, indulge in. . . it is nevertheless the nearest approach to a London square that is to be found in Philadelphia. . . “The Delaware river, above Philadelphia, still flows through a landscape too level for beauty, but it is rendered interesting by a succession of gentlemen’s seats, which, if less elaborately finished in architecture, and garden grounds, than the lovely villas on the Thames, are still beautiful objects to gaze upon as you float rapidly past on the broad silvery stream that washes their lawns.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, January 1837, “Notices on the State and Progress of Horticulture in the United States,” describing Hyde Park, seat of David Hosack, on the Hudson, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 3: 5)[30]

- “The most distinguished amateur and patron of gardening, in every sense of the word, in this state, was the late Dr. Hosack. Hyde Park, on the Hudson, the seat of this gentleman, has been probably the best specimen of a highly improved residence in the United States.”

- Ritchie, Anna Cora Ogden Mowatt, 1839, describing Bonaparte’s Park at estate of Joseph Bonaparte (Count de Survilliers), Bordentown, NJ (quoted in Weber 1854: 186)[31]

- “Equally rustic seats are scattered beneath the shade of the tall trees on its banks, and upon its clear surface a flock of snow-white swans were floating about.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), September 1840, “Notes on Gardens and Gardening, in New Bedford, Mass.,” describing the estate of James Arnold, New Bedford, MA (Magazine of Horticulture 6: 364)[32]

- “Continuing through the winding walks, shady bowers, and umbrageous retreats, through which rustic seats were placed, we arrived at the shell grotto.”

- Adams, Nehemiah, 1842, describing Boston Common, Boston, MA (1842: 54)[33]

- “One of the next improvements in the Common we suspect will be a suitable supply of proper seats in the mall. As a defence against our American propensity to whittle, the city government caused some of the wooden seats to be sheathed with sheet iron. Vain defence against the knife of an American whittler! . . . The city government thought that they would ‘try what virtue there is in stones.’ Blocks of granite have been deposited there for seats. . . The stone seats are smooth only on the upper side, and their rough look is not strictly in Boston taste, though it is excusable, considering the penitentiary object which led to their substitution for wooden seats. . . The idea of sitting on a natural, rough rock, to enjoy the beauties of nature, is poetical and in good keeping, but we have tried in vain to make those stone seats on the mall seem poetical.”

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1842, describing Red Sulphur Springs, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “In the centre of the valley, is a triangular plot of grass, which has been enclosed with well-finished rails, painted white, and laid out in walks like a lawn, having also several large and fine trees, under which seats are placed for enjoying the shade.”

- Anonymous, December 6, 1842, “Letter from Ministry at New Lebanon to Ministry at Graveland” (Western Reserve Historical Society Library, Shaker Manuscript Collection)

- “And it is my will that your seats be prepared after the following order. Ye may take boards of sufficient width & thickness to form a seat. These may be planed. Place these upon square blocks of sufficient bigness to elevate the seat of a suitable height; and these are sufficient for seats, upon my holy ground. And if ye desire to build a shed, near by the meeting ground under which you can place these seats, at such parts of the year as they are not wanted, ye may freely do it; but if my feast ground is located near your dwellings, you had better carry them there to place under shelter.”

- Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth, c. 1845, describing the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Evans 1993: 41)[34]

- “Made the flower garden; laying it out in the form of a Lyre. Built also the rustic seat in the Old Apple tree. Set out the roses under the Library windows.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1847, describing Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (quoted in Haley 1988: 20, 47, 50)[35]

- “I forgot to beg you before you leave Montgomery Place to sketch the view from the bold rustic seat with rustic balustrade in front*on the high west river walk. It seems to me one of the very finest things I have seen anywhere.

- * that seat about half way between the steps & the south terminus. . .

- “A path on the left of the broad lawn leads one to the fanciful rustic-gabled seat, among a growth of locusts at the bottom of the slope. . . Half-way along this morning ramble, a rustic seat, placed on a bold little plateau, at the base of a large tree, eighty feet above the water, and fenced about with a rustic barrier, invites you to linger and gaze at the fascinating river landscape here presented. . .

- “A little farther on, we reach a flight of rocky steps, leading up to the border of the lawn. At the top of these is a rustic seat with a thatched canopy, curiously built round the trunk of an aged pine. . .

- “This part of the grounds [the lake] is seen to the most advantage, either toward evening, or in moonlight. Then the effect of contrast in light and shadow is most striking, and the seclusion and beauty of the spot are more fully enjoyable than at any hour. Then you will most certainly be tempted to leave the curious rustic seat, with its roof wrapped round with a rude entablature like Pluto’s crown.” [Fig. 11]

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., April 1848, describing the pleasure grounds and farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia (American Journal of Insanity 4: 349)[36]

- “The summer-houses, rustic-seats, exercising-swings &c., in this division are all in particularly pleasant positions. The cottage fronts the woods, and in every part this portion of the grounds is completely protected from intrusion and observation.” [Fig. 12]

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1850, describing the public gardens in Philadelphia, PA (1850: 332–33)

- “856. Public Gardens. . .

- “Promenade at Philadelphia. There is a very pretty enclosure before the walnut tree entrance to the state-house, with good well-kept gravel walks, and many beautiful flowering trees. It is laid down in grass, not in turf; which, indeed, Mrs. Trollope observes, ‘is a luxury she never saw in America. Near this enclosure is another of a similar description, called Washington Square, which has numerous trees, with commodious seats placed beneath their shade.’ (Ibid. [D. M. &c.] vol. ii. p. 48.) . . .

- “Waterworks at Fair Mount, near Philadelphia. ‘. . . On the farther side of the river is a gentleman’s seat, the beautiful lawn of which slopes down to the water’s edge; and groups of weeping willows and other trees throw their shadows on the stream.’ (Domestic Manners of the Americans, vol. ii. p. 44.)”

Citations

- Dezallier d’Argenville, Antoine-Joseph, 1712, The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712: 78)[37]

- “SEATS, or Benches, besides the Conveniency they constantly afford in great Gardens, where you can scarce ever have too many, there is such need of them in walking, look very well also in a Garden, when set in certain Places they are destin’d to, as in the Niches or Sinkings that face principal Walks and Vistas, and in the Halls and Galleries of Groves.”

- Ware, Isaac, 1756, A Complete Body of Architecture (1756: 636, 641)[38]

- “The first principle is here that there be space to walk, and seats to rest. These must be proportioned also to one another: it would be absurd to terminate a vast walk with a plain bench; nor less ridiculous to erect a pompous temple where there was not the extent of a hundred yards from the building. . .

- “He who would know where to place his pavilion, seat, or temple, in a garden, must first understand what the purpose of it is, and what the true beauty and excellence of the garden itself.”

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (1789: n.p.)[39]

- “SEAT, se’t. s. A chair, bench, or any thing on which one may sit; chair of state; tribunal; mansion, abode; situation, site.”

- Anonymous, 1798, Encyclopaedia (1798: 7:561)

- “‘V. SEATS have a two-fold use; they are useful as places of rest and conversation, and as guides to the points of view in which the beauties of the surrounding scene are disclosed. Every point of view should be marked with a seat; and speaking generally, no seat ought to appear but in some favourable point of view. This rule may not be invariable, but it ought seldom to be deviated from.

- “In the ruder scenes of neglected nature, the simple trunk, rough from the woodman’s hands, and the butts or stools of rooted trees, without any other marks of tools upon them than those of the saw which severed them from their stems, are seats in character; and in romantic or recluse situations, the cave or the grotto are admissible. But wherever human design has been executed upon the natural objects of the place, the seat and every other artificial accompaniment ought to be in unison; and whether the bench or the alcove be chosen, it ought to be formed and finished in such a manner as to unite with the wood, the lawn, and the walk, which lie around it.

- “The colour of seats should likewise be suited to situations: where uncultivated nature prevails, the natural brown of the wood itself ought not to be altered; but where the rural art presides, white or stone colour has a much better effect.’ Practical Treatise on Planting and Gardening p. 593 &c.”

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803: 69, 153)[40]

- “This would be a proper place for a covered seat, with a shed behind it for horses or open carriages; but it should be set so far back as to command the view under the branches of trees, which are very happily situated for the purpose. . .

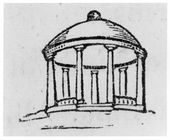

- “Yet the summit of a naked brow, commanding views in every direction, may require a covered seat or pavilion; for such a situation, where an architectural building is proper, a circular temple with a dome, such as the temple of the Sybils, or that of Tivoli, is best calculated.”

- Abercrombie, John, with James Mean, 1817, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener (1817: 465)[41]

- “Fine points of view claim, in the first place, to be distinguished by seats. Seats merely serving as places of rest might announce an intrinsic object by some difference in their construction; and if there be no distant prospect to engage attention, greater elegance in the accompaniments may create a pleasant resting-place. As to the manner of finishing a seat; where the house is in sight, a correct taste will expect the bench or alcove to correspond with the style of the house, so far at least as to be avowedly artificial, neat in the workmanship, and painted. In neglected or wild scenes, withdrawn from the polished lawn, pleasing illusions may be induced by a rough block of timber, the arms of a fantastic root, or forest fagots romantically interwoven, offering a seat under the canopy of a tree, or within a cave or grotto. This is admissible on principle, in proportion as every thing surrounding is in character. Not that it can be denied, that whimsical seats at variance with the situation sometimes afford a degree of amusement, and may do no harm in little gardens, or in a scene too tame to be spoiled: but the effect terminates with the oddity; a place destitute of character can excite no romantic interest.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 355, 357, 809)[42]

- “1805. Of convenient decorations the variety is almost endless, from the prospect-tower to the rustic seat; besides aquatic decorations, agreeable to the eye and convenient for the purposes of recreations or culture. Their emplacement, as in the former section, belongs to gardening, and their construction to architecture and engineering. . .

- “1816. Roofed seats, boat-houses, moss houses, flint houses, bark huts, and similar constructions, are different modes of forming resting-places containing seats, and sometimes other furniture or conveniences in or near them. . . [Fig. 13]

- “1817. Roofed seats of a more polished description are boarded structures generally semi-octagonal, and placed so as to be open to the south. Sometimes they are portable, moving on wheels, so as to be placed in different positions, according to the hour of the day, or season of the year, which, in confined spots, is a desirable circumstance. Sometimes they turn on rollers, or on a central pivot, for the same object, and this is very common in what are called barrel-seats. In general they are opaque, but occasionally their sides are glazed, to admit the sun to the interior in winter.

- “1818. Folding chairs. A sort of medium seat, between the roofed and the exposed, is formed by constructing the backs of chairs, benches, or sofas with hinges, so as they may fold down over the seat, and so protect it from rain. . .

- “1819. Elegant structures of the seat kind for summer use, may be constructed of iron rods and wires, and painted canvas; the iron forming the supporting skeleton, and the canvass the protecting tegument. . . [Fig. 14]

- “1820. Exposed seats include a great variety, rising in gradation from the turf bank to the carved couch. Intermediate forms are stone benches, root stools, sections of trunks of trees, wooden, stone, or cast-iron mushrooms painted or covered with moss, or mat, or heath; the Chinese barrel-seat, the rustic stool, chair, tripod, sofa, the cast-iron couch or sofa, the wheeling-chair, and many subvarieties. . .

- “6157. . . Light bowers formed of lattice-work, and covered with climbers, are in general most suitable to parterres; plain covered seats suit the general walks of the shrubbery.”

- Anonymous, April 26, 1826, “On Landscapes and Picturesque Gardens” (New England Farmer 4: 316)[43]

- “A few fabrics, rustic bridges, hermitages, a Temple, or a Chinese Kiosk or Pagoda, not expensive in their execution, would advantageously complete the embellishment of a country seat.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[44]

- “SEAT, n. [It. sedia; Sp. sede, sitio, from L. sedes, situs; Sw. sate; Dan. soede; G. sitz; D. zetel, zitplaats; W. sez; Ir. saidh; W. with a prefix, gosod, whence gosodi, to set. See Set and Sit. . .]

- “1. That on which one sits. . .

- “3. Mansion; residence; dwelling; abode; as Italy the seat of empire. The Greeks sent colonies to seek a new seat in Gaul.

- “In Alba he shall fix his royal seat. Dryden.

- “4. Site; situation. The seat of Eden has never been incontrovertibly ascertained. . .

- “8. The place where a thing is settled or established. London is the seat of business and opulence. So we say, the seat of the muses, the seat of arts, the seat of commerce.”

- Bridgeman, Thomas, 1832, The Young Gardener’s Assistant (1832: 111)[45]

- “In a retired part of the [flower] garden, a rustic seat may be formed, over and around which honey-suckles and other sweet and ornamental creepers and climbers may he [sic] trained on trellises, so as to afford a pleasant retirement.”

- Teschemacher, James E., August 1, 1835, “Extracts from Foreign Publications” (Horticultural Register 1: 308–9)[46]

- “From an article On the various form and character of Arbours as objects of use or ornament either in gardens or wild scenery [from Paxton’s Horticultural Register], we extract the following passages. . .

- “‘The closely shaven turf comes about ten feet inside the arches where its edge is cut, and between that and the basin is covered with a fine tawny sand, with an apparently confused but really symmetrical arrangement of marble pedestals, seats and vases with flowering plants placed upon them. During summer a vase with a rare flowering plant is placed under each of the external arches except four which serve as entrances. The entire effect is good, and his may be considered as one of the best specimens of the artificial bower of the present day.’”

- Sayers, Edward, 1838, The American Flower Garden Companion (1838: 14, 19, 131)[47]

- “At country residences, where a large extent is appropriated to this department [the flower garden], many convenient and pleasing appendages can be judiciously introduced; as rustic arbors, rustic seats, and rockery; and if water can be connected, it always gives a good effect. All such appendages, I recommend to be constructed in as natural a manner as possible. . .

- “In extensive pleasure grounds the rockery has a good effect when placed distinct from the flower garden, and near a rustic arbor or ornamental bridge, or seat; and if placed by the side of a retired walk, near the lawn or grass plot, it has an easy effect. . . .

- “the margin of the pond should be planted with drooping willows and trees of a pendulous habit for shade, under which rustic seat might be properly placed for the accommodation of those who desire to view the sporting fishes, and other interesting objects by which they are surrounded.”

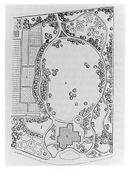

- Walsh, Alexander, March 31, 1841, “Remarks on Ornamental Gardening” (New England Farmer 19: 308–9)[48]

- “The garden and pleasure ground I would describe, is of an oblong form, 165 feet by 120 feet, with one end next the north side of the house. . .

- “X X two seats, each occupying 2 ft. . . T T two seats. . . surrounded by an arched arbor 10 ft. high, thrown over the walk, ornamented on one side with honeysuckle, on the other by climbing Boursaut rose.” [Fig. 15]

- Loudon, Jane, 1843, Gardening for Ladies (1843: 283–84)[49]

- “SEATS for gardens are either open or covered; the latter being in the form of root-houses, huts, pavilions, temples, grottoes, &c., and the former being either fixed, temporary, or portable. Fixed seats are commonly of stone, either plain stone benches without backs, or stone supports to wooden benches. Sometimes, also, wooden seats are fixed, as when they are placed round a tree, or when boards are nailed to posts, or when seats are formed in imitation of mushrooms, as in the grounds at Redleaf. Fixed seats are also sometimes formed of turf. Portable seats are formed of wood, sometimes contrived to have the back of the seat folded down when the seat is not in use; so as to exclude the weather, and avoid the dirt of birds which are apt to perch on them. Another kind of portable seat, which is frequently formed in iron, as shown in fig. 49, is readily wheeled from one part of the grounds to another; and the back of which also folds down to protect the seat from the weather. There is a kind of camp-stool which serves as a portable seat, imported from Norway, and sold at the low price of 2s. 6d. or 3s.; and there are also straw seats, like half beehives, which are, however, only used in garden-huts, or in any situation under cover, because in the open air they would be liable to be soaked with rain. There are a great variety of rustic seats formed of roots and crooked branches of trees, used both for the open garden and under cover; and there are also seats of cast and wrought iron, of great variety of form. There should always be some kind of analogy between the seat and the scene of which it forms a part; and for this reason rustic seats should be confined to rustic scenery; and the seats for a lawn or highly kept pleasure-ground ought to be of comparatively simple and architectural forms, and either of wood or stone, those of wood being frequently painted of a stone colour, and sprinkled over with silver sand before the paint is dry, to give them the appearance of stone. Iron seats, generally speaking, are not sufficiently massive for effect; and the metal conveys the idea of cold in winter and heat in summer. [Fig. 16]

- “When seats are placed along a walk, a gravelled recess ought to be formed to receive them; and there ought, generally, to be a footboard to keep the feet from the moist ground, whether the seat is on gravel or on al awn [sic]. In a garden where there are several seats, some ought to be in positions exposed to the sun, and others placed in the shade, and none ought to be put down in a situation where the back of the seat is seen by a person approaching it before the front. Indeed the backs of all fixed seats ought to be concealed by shrubs, or by some other means, unless they are circular seats placed round a tree. Seats ought not to be put down where there will be any temptation to the persons sitting on them to strain their eyes to the right or left, nor where the boundary of the garden forms a conspicuous object in the view. In general, all seats should be of a stone colour, as harmonizing best with vegetation. Noting can be more unartistical than seats painted a pea-green, and placed among the green of living plants.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849: 454–56, 473–74)[50]

- “Open and covered seats, of various descriptions, are among the most convenient and useful decorations for the pleasure-grounds of a country residence. Situated in portions of the lawn or park, somewhat distant from the house, they offer an agreeable place for rest or repose. If there are certain points from which are obtained agreeable prospects or extensive views of the surrounding country, a seat, by designating those points, and by affording us a convenient mode of enjoying them, has a double recommendation to our minds.

- “Open and covered seats are of two distinct kinds; one architectural, or formed after artist-like designs, of stone or wood, in Grecian, Gothic, or other forms; which may, if they are intended to produce an elegant effect, have vases on pedestals as accompaniments; the other, rustic, as they are called, which are formed out of trucks and branches of trees, roots, etc., in their natural forms. . .

- “We consider rustic seats and structures as likely to be much preferred in the villa and cottage residences of the country. They have the merit of being tasteful and picturesque in their appearance, and are easily constructed by the amateur, at comparatively little or no expense. There is scarcely a prettier or more pleasant object for the termination of a long walk in the pleasure-grounds or park, than a neatly thatched structure of rustic work, with its seat for repose, and a view of the landscape beyond. . . [Fig. 17]

- “Unity of expression is the maxim and guide in this department of the art, as in every other. . .

- “With regard to pavilions, summer-houses, rustic seats, and garden edifices of like character, they should, if possible, in all cases be introduced where they are manifestly appropriate or in harmony with the scene. Thus. . . a rustic covered seat may occupy a secluded, quiet portion of the grounds, where undisturbed meditation be enjoyed.”

- Ranlett, William H., 1849, The Architect (1849; repr., 1976: 1:19)[51]

- “Probably no portion of the globe, offers a greater variety of beautiful country seats than the vicinity of New-York. No man who has any taste for the retired tranquillity of a suburban retreat, or the lovely beauty of a picturesque scene, or the romantic grandeur of an enchanting landscape of cities, towns and country; rivers, bays and ocean, could fail to be suited with some of the numerous situations on the undulated shores, gentle declivities or towering heights of Staten Island, Long Island or the banks of the noble Hudson.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1850, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850; repr., 1968: 80–81)[52]

- “The little rustic arbors or covered seats on the outside of the bay window may be supposed to answer in some measure in the place of a veranda, and convey at the first glance, an impression of refinement and taste attained in that simple manner so appropriate to a small cottage.” [Fig. 18]

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, June 1850, “Our Country Villages” (Horticulturist 4: 540–41)[53]

- “The next step, after the possession of such public pleasure-grounds, would be the social and common enjoyment of them. Upon the well-mown glades of lawn, and beneath the shade of the forest trees, would be formed rustic seats. Little arbors would be placed near, where in midsummer evenings ices would be served to all who wished them.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, March 1851, “The Management of Large Country Places” (Horticulturist 6: 105–6)[54]

- “All our country residences may readily be divided into two classes. The first and largest class, is the suburban place of from five to twenty or thirty acres; the second is the country-seat, properly so called, which consists of from 30 to 500 or more acres. . .

- “But in the larger country places, there are ten instances of failure for one of success. This is not owing to the want of natural beauty, for the sites are picturesque, the surface varied, and the woods and plantations excellent. The failure consists, for the most part, in a certain incongruity and want of distinct character in the treatment of the place as a whole. They are too large to be kept in order as pleasure-grounds, while they are not laid out or treated as parks. The grass which stretches on all sides of the house, is partly mown for lawn, and partly for hay; the lines of the farm and the ornamental portion of the grounds, meet in a confused and unsatisfactory manner, and the result is a residence pretending to be much superior to a common farm, and not yet rising to the dignity of a really tasteful country seat.”

- Jaques, George, January 1852, “Landscape Gardening in New-England” (Horticulturist 7: 35)[55]

- “Let woodbine, honey-suckle and climbing roses, here entwine themselves around a column, and wreath themselves there over a window. Here place a rustic seat, half hid among the shrubbery; there lead a short walk, carelessly curving towards a little vine-clad arbor.”

Images

Inscribed

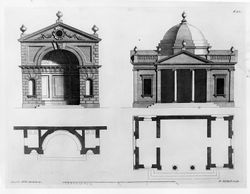

James Gibbs, “Two Seats for the ends of Walks,” in A Book of Architecture (1728), pl. 82.

James Gibbs, “Two other Seats for the same purpose [for the ends of walks],” in A Book of Architecture (1728), pl. 83.

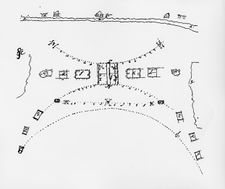

Samuel Vaughan, Plan of Bath (Berkeley Springs), VA, 1787, from the diary of Samuel Vaughan, June–September 1787.

Anonymous, A View of Mount Vernon, c. 1790.

Jeremiah Paul, “Robert Morris’ Seat on Schuylkill,” July 20, 1794.

Charles Fraser, Rice Hope: The Seat of Dr. William Read, Taken from One of the Rice Fields, c. 1800.

Alexander Robertson (artist), Francis Jukes (engraver), “Mount Vernon in Virginia,” 1800.

William Russell Birch, “Mount Vernon, Virginia, the Seat of the late Genl. G. Washington,” in The Country Seats of the United States (1808), pl. 7.

William Russell Birch, “Woodlands, the Seat of Mr. Wm. Hamilton, Pennsylva.,” in The Country Seats of the United States (1808), pl. 14.

William Russell Birch, “View from Belmont Pennsyla. the Seat of Judge Peters,” in The Country Seats of the United States (1808), pl.16.

Charles Willson Peale, Letter to Angelica Peale describing his garden at Belfield, November 22, 1815.

J. C. Loudon, Covered seats of the rustic kind, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed/ (1826), 357, fig. 336.

J. C. Loudon, Elegant structures of the seat kind, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 357, figs. 337 and 338.

J. C. Loudon, Rough bench in rustic hut decorated in shrubberies, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 809, fig. 561.

J. C. Loudon, “Seat formed of moss and hazel rods" and "Trellised arches for climbers,” in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, new ed. (1834), 1196, figs. 960–62.

J. C. Loudon, A rustic seat, in The Suburban Gardener (1838), 467, fig. 173.

J. C. Loudon, “Covered Seat, of grotesque and rustic Masonry,” Cheshunt Cottage, in The Gardener’s Magazine 15, no. 117 (December 1839): 656, fig. 168.

J. C. Loudon, Elevation of the Back Woodwork of a Rustic Covered Seat, Cheshunt Cottage, in The Gardener’s Magazine 15, no. 117 (December 1839): 660, fig. 168.

Alexander Walsh, Two seats surrounded by an arched arbor, in New England Farmer 19, no. 39 (March 31, 1841): 309, fig. 4.

Anonymous, “Moveable Garden Seat,” in Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden (1845), 369, fig. 49.

Rustic] Seat,” Montgomery Place, in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 2, no. 4 (October 1847): 157, fig. 26.

Anonymous, “Beaverwyck, the Seat of Wm. P. Van Rensselaer, Esq.,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), pl. opp. 51, fig. 7.

Anonymous, “The Seat of George Sheaff, Esq.,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), pl. between 58 and 59, fig. 12.

Anonymous, “Plan of a Suburban Villa Residence,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 118, fig. 26.

Anonymous, “A circular pavilion,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 456, fig. 81.

Anonymous, “Simple rustic seat,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 456, fig. 82.

Anonymous, Simple rustic seat made at the foot of a tree, in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 456, fig. 83.

Anonymous, “Covered seat or rustic arbor,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 457, fig. 84.

Anonymous, Covered Seat for a mineral, shell, or geological collection, in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 457, fig. 85.

Anonymous, “Rustic Covered Seat,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 458, fig. 86.

Anonymous, “Mount Fordham—the Country Seat of Lewis G. Morris, Esq.,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 6, no. 8 (August 1851): pl. opp. 345.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Shore Seat for Montgomery Place, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York (elevation and plan), 1870—79.]]

Associated

Anonymous, Plan of the Harvard Botanic Garden, early 19th century.

William Russell Birch, “Mendenhall Ferry, Schuylkill, Pennsylvania,” The Country Seats of the United States (1808), pl. 18.

William Strickland, “The Woodlands,” 1809, in Casket 5, no. 10 (October 1830): pl. opp. 432.

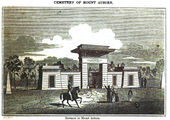

Anonymous, “Entrance to Mount Auburn,” in American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge 1, no. 1 (September 1834): 9.

John T. Bowen, A View of Fairmount Water-Works with Schuylkill in the distance, taken from the Mount, 1838.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Montgomery Place—Shore Seat, c. 1847.

Alexander Jackson Davis, “Montgomery Place,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 2, no. 4 (October 1847): pl. between 152 and 153.

Anonymous, “The Lake,” Montgomery Place, in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 2, no. 4 (October 1847): 158, fig. 27.

Thomas S. Sinclair, “Plan of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane at Philadelphia,” in Thomas S. Kirkbride, American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4 (April 1848): pl. opp. 280.

Anonymous, “View in the Meadow Park at Geneseo,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 3, no. 4 (October 1848): pl. opp. 153.

Alexander Jackson Davis, “View in the Grounds at Blithewood,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), frontispiece.

Anonymous, “View in the Grounds at Hyde Park,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), pl. opp. 45, fig. 1.

Anonymous, “View in the Grounds of James Arnold, Esp.,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), pl. opp. 57.

Anonymous, “Small Bracketed Cottage,” in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. 78, fig. 9.

Attributed

Charles Fraser, Rice Hope, Taken from One of the Rice Fields, c. 1803.

Anne-Marguerite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny Hyde de Neuville, attr., Tomb du grande Washington au Mount Vernon, 1818.

Alexander Jackson Davis, “View of the Battery and Castle Garden,” 1826–28.

Alexander Jackson Davis, “View of St. John’s Chapel, from the park,” 1829.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Ithiel Town, and James Dakin, New York University, Washington Square, 1833.

Anonymous, “Forest Pond,” in The Picturesque Pocket Companion, and Visitor’s Guide, through Mount Auburn (1839), 171.

W. Mason, “Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane,” c. 1841, in Thomas S. Kirkbride, Reports of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane: for the Year 1841 (1841), frontispiece.

James Smillie, “Mount Auburn Cemetery,” in Cornelia W. Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated (1847; repr., 1850), frontispiece.

Anonymous, “The Bracketed Mode,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 393, fig. 52.

Notes

- ↑ Emily Tyson Cooperman, “William Russell Birch (1755–1834) and the Beginnings of the American Picturesque” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1999), view on Zotero. See also Emily T. Cooperman, introduction to The Country Seats of the United States of North America, by William Russell Birch (1808; repr., Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2009), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bainter O’Neal, Jefferson’s Fine Arts Library: His Selections for the University of Virginia Together with His Own Architectural Books (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976), 57, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David B. Chase, “The Beginnings of the Landscape Tradition in America,” Historic Preservation 25 (1973): 34–41, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Louis B. Wright and Virginia Freund, eds., The Historie of Travell into Virginia Britania (1612) (Nendeln and Liechtenstein: Kraus, 1967), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Marion Tinling, ed., The Correspondence of the Three William Byrds of Westover, Virginia, 1684–1776, 2 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1977), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gregory A. Stiverson and Patrick H. Butler III, eds., “Virginia in 1732: The Travel Journal of William Hugh Grove,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 85 (1977): 18–44, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 H. Paul Caemmerer, The Life of Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, Planner of the City Beautiful, The City of Washington (Washington, DC: National Republic Publishing Company, 1950), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Lee Shippen, Westover Described in 1783: A Letter and Drawing Sent by Thomas Lee Shippen, Student of Law in Williamsburg, to His Parents in Philadelphia (Richmond, VA: William Byrd Press, 1952), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Parker Cutler, Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D. (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Karen Madsen, “To Make His Country Smile: William Hamilton’s Woodlands,” Arnoldia 49 (1989): 14–23, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constantia [Judith Sargent Murray], “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania,” Massachusetts Magazine, or, Monthly Museum of Knowledge and Rational Entertainment 7, no. 3 (July 1791): 413–17, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Henry Wansey, Henry Wansey and His American Journal, ed. David John Jeremy (1794; repr., Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1970), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Arthur Hammond, “‘Where the Arts and the Virtues Unite’: Country Life Near Boston, 1637–1864” ( PhD diss., Boston University, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Timothy Dwight, Travels; in New-England and New-York, 4 vols. (New Haven: The Author, 1821–22), view on Zotero.

- ↑ François-Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, Travels through the United States of North America, the Country of the Iroquois, and Upper Canada, in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797, ed. Brisson Dupont and Charles Ponges, trans. H. Newman, 2nd ed., 4 vols. (London: R. Philips, 1800), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Karen Madsen, “William Hamilton’s Woodlands,” (paper presented for seminar in American Landscape, 1790–1900, instructed by E. McPeck, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John C. Ogden, An Excursion into Bethlehem & Nazareth, in Pennsylvania, in the Year 1799 (Philadelphia: Charles Cist, 1800), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Flowers, “People and Plants: North Carolina’s Garden History Revisited,” Eighteenth Century Life 8 (1983): 117–29, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Scott, A Geographical Description of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Printed by R. Cochran, 1806). view on Zotero.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Flora Ann L. Bynum, Old Salem Garden Guide (Winston-Salem, NC: Old Salem, 1979), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, ed. Gaillard Hunt (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1906), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sir Augustus John Foster, Jeffersonian America: Notes on the United States of America Collected in the Years 1805–1806–1807 and 1811–1812, ed. Richard Beale Davis (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1954), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Lambert, Travels through Canada, and the United States of North America in the Years 1806, 1807, and 1808, 2 vols. (London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), [1].

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller and et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 5, The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Mork Gibson, “The Fairmount Waterworks,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 84 (1988): 5–40, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nina Fletcher Little, Early Years of the McLean Hospital, Recorded in the Journal of George William Folsom, Apothecary at the Asylum in Charlestown (Boston: Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, 1972), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Hebron Moore, “A View of Philadelphia in 1829: Selections from the Journal of B. L. C. Wailes of Natchez,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 78 (July 1954): 353–60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans, 3rd ed., 2 vols. (London: Wittaker, Treacher, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “Notices on the State and Progress of Horticulture in the United States,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 3, no. 1 (January 1837): 1–10, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constance Weber, “A Sketch of Joseph Bonaparte,” in Godey’s Lady’s Book (Philadelphia: L. A. Godey, 1854), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes on Gardens and Gardening, in New Bedford, Mass.,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 6, no. 9 (September 1840): 361–66, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Adams, Boston Common (Boston: William D. Ticknor and H. B. Williams, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Catherine Evans, Cultural Landscape Report for Longfellow National Historic Site, History and Existing Conditions (Boston: National Park Service, North Atlantic Region, 1993), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jacquetta M. Haley, ed., Pleasure Grounds: Andrew Jackson Downing and Montgomery Place (Tarrytown, NY: Sleepy Hollow Press, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, “Description of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, with Remarks,” American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4 (April 1848): 347–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A.-J. (Antoine Joseph) Dézallier d’Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening; Wherein Is Fully Handled All That Relates to Fine Gardens, . . . Containing Divers Plans, and General Dispositions of Gardens. . . , trans. John James (London: Geo. James, 1712), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Isaac Ware, A Complete Body of Architecture (London: T. Osborne and J. Shipton, 1756), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas A. Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews. . . , 5th ed. (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Abercrombie, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener Or, Improved System of Modern Horticulture (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1817), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826),view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “On Landscape and Picturesque Gardens,” New England Farmer 4, no. 40 (April 28, 1826): 316, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Bridgeman, The Young Gardener’s Assistant, 3rd ed. (New York: Geo. Robertson, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James E. Teschemacher, “Extracts from Foreign Publications,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 1 (August 1, 1835): 304–9, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Sayers, The American Flower Garden Companion, Adapted to the Northern States (Boston: Joseph Breck, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Walsh, “Remarks on Ornamental Gardening, With a Plan of a Fruit, Flower and Vegetable Garden,” New England Farmer, and Horticultural Register 19, no. 39 (March 31, 1841): 308–9, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; And Companion to the Flower-Garden, ed. A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1843), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America. . . , 4th ed. (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William H. Ranlett, The Architect, 2 vols. (1849–51; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses; Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-Houses, and Villas (1850; repr., New York: D. Appleton; Da Capo, 1968), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “Our Country Villages,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 4, no. 12 (June 1850): 537–41, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “The Management of Large Country Places,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 6, no. 3 (March 1851): 105–8, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Jacques, “Landscape Gardening in New-England,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 7, no. 1 (January 1852): 33–36, view on Zotero.