Arbor

(Arber, Arbour, Herber)

See also: Bower, Espalier

History

One of the earliest written descriptions of an arbor, as understood by Anglo-American travelers and settlers, comes from William Strachey’s statement in 1612 that the houses of indigenous peoples of Virginia were “like gardein arbours”: covered shelters made of tightly knit vegetation, large enough to accommodate several people (). In design, this structure corresponds with what John James’s translation (1712) of French treatise writer A.-J. Dézallier d’Argenville described as a “natural” arbor, made by manipulating existing vegetation with artificially introduced supports (as opposed to an “artificial” arbor, fabricated from introduced materials, such as lattices) (view text).

Despite Dezallier d’Argenville’s attempt to define arbor with great specificity, many pre-19th-century accounts of gardens in America describe arbors only vaguely, perhaps due to the overlap between arbor and bower, which were nearly interchangeable in dictionary definitions of this period. For example, Ephraim Chambers (1741–43), Samuel Johnson (1755), and Thomas Sheridan (1789) each defined an arbor as a bower.[1] Nevertheless, European treatise writers, such as Dezallier d’Argenville (1712), argued for differences between arbors and bowers, perhaps reflecting the arbor’s origins in distinct 17th-century garden structures built to provide shade, such as berceaux, cabinets, galleries, and salons. In the American context, lexicographer Noah Webster also attempted to maintain a distinction between arbors and bowers, using shape as the distinguishing factor: bowers were “round or square” whereas arbors were “long and arched” (view text).

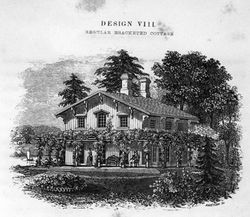

Webster’s 1828 definition of arbor—a lattice frame covered with vegetation—corresponds to the most common arbor form in 19th-century America. This frame could be composed of a variety of materials, from Thomas Jefferson’s forked locust limbs to the finished wood employed in the arbors attached to cottages designed by A. J. Downing [See Fig. 13]. Within this general form, designs of arbors could vary, typically in correspondence to their function, and they ranged from inverted, U-shaped structures, that often bridged garden walks [Figs. 1 and 2] to structures that resembled garden seats or summerhouses.[2] Most designs could support vegetation, which enhanced their use as shaded shelters. American arbors also frequently used grapes as support vegetation. Such arbors (also called graperies) served both material and aesthetic purposes, providing both growing spaces for grapes and also structural links between different spaces and features of the garden.

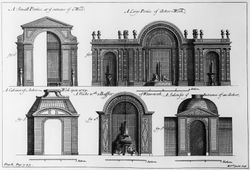

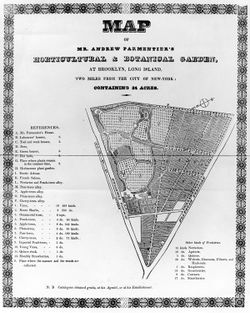

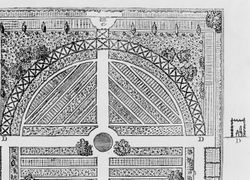

Aesthetically, arbors served to frame and punctuate garden walks and views. The “rustic” arbor at Parmentier’s Horticultural and Botanical Garden in Brooklyn, New York, for example, resembled a small, open house and served as a termination to a garden walk (it was also identified as a prospect tower) [See Fig. 11]. The arbor’s style, materials, and manner of construction were dictated by the overall style of the garden in which it was to appear. A. J. Downing, for example, adopted a “rustic style” for those arbors placed in rural or “picturesque” settings [See Fig. 6]. In several 19th-century treatises, in keeping with the developing tendency to assign stylistic forms to specific nation-states, writers (such as J. C. Loudon) distinguished between Italian and French arbor forms, which were differentiated from American forms by their greater use of elaborated decorative trellises or lattice work.

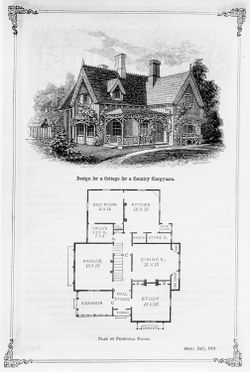

Arbors could be found in both private residential spaces, such as Father Rapp′s garden in Economy, Pennsylvania, and public gardens and grounds, such as Gray’s Tavern in Philadelphia. The shaded shelter provided by arbors led to their use as outdoor living spaces. In a design for a cottage for a country clergyman published in the Horticulturist, Downing proposed attaching an arbor to the house, near the front porches, entrance, and veranda, where it served as a shaded seating area [Fig. 3]. A number of 18th-century descriptions of arbors in America delineate their use for outdoor dining and entertainment.

Arbors could substitute for other forms of covered shelter, as in the case of the British army, which, according to Robert Honyman (1781), erected “temporary” arbors with “boughs of Trees, fence rails &c” (view text). Such comments also indicate that arbors could be either temporary structures for short-term usage or permanent additions to the designed landscape.

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Smith, John, 1612, describing Native American life in Virginia (quoted in Billings 1975: 214–15)[3]

- “Their buildings and habitations are for the most part by the rivers or not farre distant from some fresh spring. Their houses are built like our Arbors of small young springs bowed and tyed, and so close covered with mats or the barkes of trees very handsomely, that not withstanding either winde raine or weather, they are as warme as stoves.” [Fig. 4]

- Strachey, William, 1612, describing Native American settlements in Virginia (quoted in Wright and Freund, eds., 1967: 78)[4]

- “As for their [Indian] howses, who knoweth one of them knoweth them all, even the Chief kings house yt self, for they be all alike builded one to another, they are like gardein arbours, (at best like our sheppardes Cottages,) made yet handsomely enough, though without strength or gaynes; Gaynes: gain B, notches, or mortises, as in a timber, wall, etc. for a gorder or oint. of such young plants as they can pluck up, bow, and make the greene toppes meete togither in fashion of a rownd roofe, which they thatch with mattes, throwne over, the walls are made with barkes of trees.” back up to History

- Anonymous, February 9, 1734, describing a property for sale on Hog-Island, near Charleston, SC (South Carolina Gazette)

- “On the Island is a New Dwelling House [with]. . . A delightful Wilderness with shady Walks and Arbours, cool in the hottest Seasons. A piece of Garden-ground where all the best kinds of Fruits and Kitchen Greens are produced planted with Orange-, Apple-, Peach-, Nectarine-, and Plumb-trees.”

- Anonymous, October 28, 1736, describing a rental property in Wicaco, PA (Pennsylvania Gazette)

- “The House late of Philip Johns, deceased, near the Swede’s Church at Wicaco; with a Garden, a small Orchard, some Pasture Ground, Brewhouse, Stable, and Arbors convenient for entertaining Company; the House being very accustomed as a Tavern.”

- Anonymous, 1746, describing the celebration of the English victory at Culloden in Newcastle, VA (quoted in Lounsbury, ed., 1994: 7)[5]

- “ . . . where a handsome Dinner was provided; along Arbour was set up, in which 50 Gentlemen and Ladies din’d.”

- Honyman, Robert, 1781, describing Hanover County, VA (1939: 401)[6]

- “There was not one Tent in the British army, all of them lying under temporary sheds or arbours, made with boughs of Trees, fence rails &c., even officers of the highest rank.” back up to History

- Anonymous, 1784, describing a barbecue in Westmoreland County, VA (quoted in Lounsbury, ed., 1994: 8)[5]

- “We then dine[d] sumptuously under a large shady tree or an arbour made of green bushes.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 14, 1787, describing Gray’s Tavern, Philadelphia, PA (1888: 1:275)[7]

- “We then rambled over the Gardens, which are large—seemed to be in a number of detached areas, all different in size and form. The alleys were none of them straight, nor were there any two alike. At every end, side, and corner, there were summer-houses, arbors covered with vines or flowers, or shady bowers encircled with trees and flowering shrubs, each of which was formed in a different taste.”

- Constantia [Judith Sargent Murray], June 24, 1790, “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania” (Massachusetts Magazine 3: 415)[8]

- “At every turn shaded seats are artfully contrived, and the ground abounds with arbours, alcoves, and summer houses, which are handsomely adorned with odoriferous flowers.”

- Southgate, Eliza, July 6, 1802, describing Elias Hasket Derby Farm, Peabody, MA (quoted in Kimball 1940: 76)[9]

- “ . . . at the upper end of the garden there was a beautiful arbour formed of a mound of turf and ’twas surrounded by a thick row of poplar trees which branched out quite to the bottom and so close together that you could not see through.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, c. 1804, describing improvements for Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (quoted in Martin 1991: 157)[10]

- “Through the whole line [of temples] from 1. to 4. have the walk covered by an arbor, to wit, locust forks set in the group crossed by poles at top & lathes on these. Grape vines principally to cover the top. The sides quite open.”

- Anonymous, October 3, 1828, “Parmentier’s Horticultural Garden,” describing Parmentier’s Horticultural and Botanical Garden, Brooklyn, NY (New England Farmer 7: 85)[11]

- “To the left of the garden an avenue leads to a Rustic Arbor curiously constructed of the crooked limbs of trees, in their rough state, covered with bark and moss; from the top of this arbor a view of the whole garden, and the surrounding scenery is exhibited, extending to Staten Island, the bay, Governor’s Island, and the city; at some distance from the rustic arbor is the French saloon, a beautiful oval, skirted with privet.” [Fig. 5]

- Buckingham, James Silk, April 1840, describing the garden of Father George Rapp, Economy, PA (1842: 2:227)[12]

- “This [the garden] covered about an acre and half of ground, and was neatly laid out in lawns, arbours, and flower-beds, with two prettily ornamented open octagonal arcades, each supporting a circular dome over a fountain.”

- Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, September 1845, describing its annual exhibition in Philadelphia (quoted in Boyd 1929: 98)[13]

- “The arbor, the second in order, was a handsome design of a square form, with a circular table in the centre, and within each, angle seats, which were occasionally occupied with lady visitors, adding to its attractions and giving the finish to the object.”

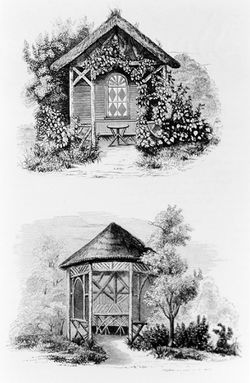

- Anonymous, January 1850, “A Few Words on Rustic Arbours” (Horticulturist 4: 320)[14]

- “The most useful and most agreeable of all these [rustic seats] is the simple rustic arbor, with projecting roof, covered with thatch or bark. I send you herewith (See FRONTISPIECE) sketches of two of these, copied from a French volume on garden decorations. I have had one of these executed in a secluded spot, and the effect is highly satisfactory, and a covered arbor like this is agreeable at all seasons of the year, when a walk in the garden is sought after. [Fig. 6]

- “Rustic work, made of branches of trees indiscriminately, and exposed to the full action of the weather, perishes very speedily. But if it is protected from the rains by being under the shelter of an overhanging roof, as for example, covered like these arbors, it will last from 10 to 15 years without repairs. But by far the best material, where it can be obtained, is the wood of red cedar, as it will endure for 20 years or more. The stems of young cedars are usually straight, and may be split in halves so as to form excellent pieces for forming the inlaying or panel-work of the insides of rustic arbors, as shown in the figures; and the larger limbs will form good pillars and lattice work for the open portions of the exterior. The frame of such arbors as these, is made by setting posts, cedar or other, with the bark on, at the corners, and then nailing rough boards between the posts, in those compartments that are to be worked close. Over these boards the halved or split rods, (those from one or two inches in diameter, are preferable), are nailed on so as to form any pleasing patterns which the taste or fancy may dictate.”

- Committee on the Capitol Square, Richmond City Council, July 26, 1851, describing John Notman’s plans for the Capitol Square, Richmond, VA (quoted in Greiff 1979: 162)[15]

- “The most beautiful feature of the contemplated alterations of the Square, however, will be found in the arrangement of the trees and shrubbery. Instead of planting these in parallel rows, like an ordinary orchard some attention will be paid to landscape gardening—groves, arbours, parterres, and fountains will combine to render the Square a place of delightful resort.”

Citations

- Parkinson, John, 1629, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629; repr., 1975: 5)[16]

- “Arbours also being both gracefull and necessary, may be appointed in such convenient places, as the corners, or elsewhere, as may be most fit, to serve both for shadow and rest after walking.”

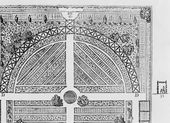

- Dezallier d’Argenville, Antoine-Joseph, 1712, The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712; repr., 1969: 71–72)

- “ARBORS are distinguish’d into two Sorts, Natural, and Artificial: Natural Arbors are formed only by the Branches of Trees artfully interwoven, and sustain’d by strong Lattice-work, Hoops, Poles, &c. which make Galleries, Porticos, Halls, and green Vistas, naturally cover’d. These Arbors are planted with Female-Elms or Dutch Lime-Trees with Horn-beam to fill up the Lower-part. . .

- “ARTIFICIAL-ARBORS and Cabinets are made wholly of Lattice-work, supported by Standards, Cross-rails, Circles and Arches of Iron. . .

- “An Arbor is distinguish’d from a Cabinet or Summer-House, in that the former is of a great Length, arched over Head in form of a Gallery; and the latter is of a Figure either square, circular, or in Cants, making a kind of Salon fit to be set at the two Ends, or in the Middle of a long Arbor. . .

- “ARBORS, Cabinets, and Porticos of Latticework, are commonly made use of to terminate a Garden in the City, and to shut out the Sight of Walls, and other disagreeable Objects; this Kind of Decoration making a handsome Sight, and serving very well to conclude the Prospect of a principal Walk.” [Fig. 7] back up to History

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741, Cyclopaedia (1741: 1:n.p.)[17]

- “ARBOUR, among gardeners, &c. a kind of shady bower or cabinet, contrived to take the air in; yet keep out the sun and rain. See GARDEN.

- “Arbours are now gone much into disuse; being apt to be damp, and unwholesome.—They are distinguished into natural and artificial.

- “Natural ARBOURS, are formed only of the branches of trees, interwoven artfully, and borne up by strong lattice-work, poles, hoops, &c. which make galleries, halls, porticoes, and green vista’s naturally covered.

- “The trees wherewith these arbours are formed, are usually the female elm, or Dutch lime-tree; in regard they easily yield, and by their great quantity of small boughs, form a thick brush-wood: the lower parts are filled up with horn-beam.

- “Artificial ARBOURS, and cabinets, are made of lattice-work, borne up by standards, cross-rails, circles and arches of iron. For which purpose they make use of small fillets of oak, which being planted and made strait, are wrought in checkers, and fastened with wire.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 1:n.p.)[18]

- “ARBOUR. n.s. [from arbor, Lat.] A bower; a place covered with green branches of trees.”

- Miller, Philip, 1759, The Gardeners Dictionary (1759: n.p.)[19]

- “These were formerly in great esteem with us than at present . . . covered seats or alcoves are everywhere at this time preferred to them. Arbours are generally made of lattice work, either in wood or in iron, and covered with Elms, Limes, Hornbeam; or with Creepers as Honeysuckles, Jasmin, or passion flowers.”

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (1789: n.p.)[20]

- “ARBOUR, a'r-bur. s. A bower.”

- Marshall, Charles, 1799, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening (1799: 1:126)[21]

- “Near some piece of water, as a cool retreat, it is desirable that there should be something of the summer-house kind, and why not the simple rustic arbour, embowered with the woodbine, the sweetbriar, the jasmine, and the rose?”

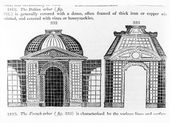

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 356)[22]

- “1811. Arbors are used as summer seats and resting-places: they may be shaded with fruit-trees, as the vine, currant, cherry; climbing ornamental shrubs, as ivy, clematis, &c.; or herbaceous, as everlasting pea, gourd, &c. They are generally formed of timber lattice-work, sometimes of woven rods, or wicker-work, and occasionally of wire.

- “1812. The Italian arbor. . . is generally covered with a dome, often framed of thick iron or copper wire painted, and covered with vines or honeysuckles.

- “1813. The French arbor. . . is characterised by the various lines and surfaces, which enter into the composition of the roof.” [Fig. 8]

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 1:n.p.)[23]

- “ARBOR, n. [The French express the sense by berceau, a cradle, an arbor, or bower; Sp. emparrade, from parra, a vine raised on stakes, and nailed to a wall. Qu. L. arbor, a tree, and the primary sense.]

- “1. A frame of lattice work, covered with vines, branches of trees or other plants, for shade; a bower.” back up to History

- Parmentier, André, 1828, “The Art of Landscape Gardening" (Fessenden, ed., 1828: 186)[24]

- “The judicious use of hermitages, arbours, cottages and rotundas will add to the effect, in picturesque gardens and ornamented farms. If you use these ornaments, place the hermitage in some retired spot. . . The rustic arbour and cottage may occupy a place less secluded.”

- James E. (James Englebert) Teschemacher, August 1, 1835, “Extracts from Foreign Publications” (Horticultural Register 1: 308–9)[25]

- “From an article on the various form and character of Arbours as objects of use or ornament either in gardens or wild scenery, we extract the following passages.

- “A singularly beautiful structure which may be classed with this kind of garden decoration has been made in Ireland.

- “A circular space of about sixty feet diameter, in the centre of dressed ground with scattered clumps of evergreen shrubs, surrounded by lofty trees, is wholly enclosed by a continued arcade of iron arches, each about five feet wide by ten feet high formed of 7–8 inch round wire to the summit of a pole in the center of the circle about thirty feet in height, so that as now described the whole presents the appearance of a skeleton circular pavilion of arches covered by a tent like roof of copper wire festoon. All the arches are thickly covered with climbing plants of strong rapid growth, which proceed along the wires to the top of the pole. Many of these are climbing roses, and the external appearance of the whole, covered with a profuse variety of luxuriant climbers interlacing and mingling their flowers and foliage is exceedingly imposing.

- “The interior is an arbor of great magnitude, not so closely covered as everywhere absolutely to exclude the sun, but yet so as to render is always shady and agreeable. In the centre a cooling fountain, where a group of nymphs support the pole, sends forth four jets d’eau, which drop with delicious murmurs into a marble basin.

- “The closely shaven turf comes about ten feet inside the arches where its edge is cut, and between that and the basin is covered with a fine tawny sand, with an apparently confused but really symmetrical arrangement of marble pedestals, seats and bases with flowering plants placed upon them. During summer a vase with a rare flowering plant is placed under each of the external arches except four which serve as entrances. The entire effect is good, and this may be considered as one of the best specimens of the artificial bower of the present day.”

- James E. (James Englebert) Teschemacher, November 1, 1835, “On Horticultural Architecture” (Horticultural Register 1: 411)[26]

- “An arbor or trellis covered with the vine, or with a variety of the clematis and climbing roses or other quick growing plants, is a good termination for a walk, which should branch off close round the trellis, to appear as if it led to a continuation elsewhere, at the back a few shrubs might conceal the boundary or fence.”

- Sayers, Edward, November 1, 1837, “On Laying out Gardens and Ornamental Plantations” (Horticultural Register 3: 410)[27]

- “In laying out grounds and ornamental gardens, many pleasing appendages may be very appropriately placed, to give a good effect, and appear to have a real meaning: as rustic arbors, ornamental seats, ornamental water, rockeries, and the like additional appendages, which, when properly placed and managed, give a finish to the grounds, and have the most pleasing effect, but when badly done, their absence is better than their presence; for, in such cases, they have the appearance of a feeble effort to accomplish the intended purpose of the design,—for instance. . . a rustic arbor exposed to the burning rays of the sun, finished in too much mechanical order, are incongruities altogether inconsistent to the purpose. . . a rustic arbor placed in a cool retreat is always admired by the visitor, after viewing the flower garden and ornamental grounds. It should be so placed that it is approached by a serpentine, or other well contrived walk, leading from the flower garden, and if possible a green sward or lawn around it, to give those who rest in it the appearance of retirement.”

- Sayers, Edward, 1838, The American Flower Garden Companion (1838: 14–15, 17–19)[28]

- “The arbors should be covered with vines and creepers, and their form not be discovered until the person who is desirous to rest, after viewing the flowers in the other departments, happens to stroll into them by an easy walk: all such places should be constructed in the shade, for retirement, and not on a rocky eminence, under the influence of the burning sun, unless a fine landscape is to be seen from them, and then an observatory is more proper. . .

- “[R]unning vines, such as Honeysuckles, Clematis, Bignonias, and so on, are most proper for covering arbors and trellises. . .

- “In many flower gardens, trellises, arbors, and summer houses, may be introduced to a very good purpose for concealing offices and unseemly appendages. . .

- “In flower gardens attached to country residences, the trellis is mostly applied to arbors, which ought to be of a rustic nature, and any form most convenient; formality in their structure, spoils the good effect they would otherwise produce.”

- Walsh, Alexander, March 31, 1841, “Remarks on Ornamental Gardening” (New England Farmer 19: 309)[29]

- “[The garden and pleasure ground should include]. . . two seats. . . surrounded by an arched arbor 10 ft. high, thrown over the walk, ornamented on one side with honeysuckle, on the other by climbing Boursaut rose—. . .

- “At the northern extremity of trellis, an arbor thrown over the walk 12 feet long, more for ornament than use; grapes in our northern latitudes ripen better on the open trellis.” [Fig. 9]

- Loudon, Jane, 1845, Gardening for Ladies (1845: 120)[30]

- “ARBOURS.—Seats or resting-places, forming terminations to walks, or fixed in retired parts of shrubberies or pleasure-grounds. In general, every straight walk ought to lead to some object of use, as well as of beauty; and an arbour is one of those in most common use. The structure being formed, climbing plants, ligneous or herbaceous, are planted all around it at the base of the trellis-work, or frame, against which, as they climb up, they ought to be tied and trained, so as to spread over the whole arbour. Some of the best plants for this purpose are the different species of Honeysuckle, Roses, and Clematis; and the Laburnum, the Periplòca graeca, the Maurandias, the Wistarias, Eccremocárpus scábra, Lophospermum, Rhodochiton, the Virginian creeper, Cobaea scándens, Menispermum canadensis, and ivy.”

- Rusticus [pseud.], August 1846, “Design for a Rustic Gate” (Horticulturist 1: 72)[31]

- “Indeed, rustic work of all kinds is extremely pleasing in any situation where there is any thing like a wild or natural character; or even where there is a simple and rustic character. In the immediate proximity of a highly finished villa, it strikes me that rustic work, such as arbors, fences, flower baskets and the like, are rather out of place. The sculptured vase of marble, or terra cotta, would appear to be the most in keeping with an elegant place of the first class; that is to say, for all situations very near the house. In wooded walks, or secluded spots, rustic work looks well always.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 63)[32]

- “ARBOUR is a seat shaded by trees. Sometimes these are trained over a wooden or iron trellis-work, mingled with the everlasting sweet pea, clematis, and other climbing odorous plants. When the trellis-work is complicated and the structure more elaborate, with a preponderance of the climbers already named, together with the honey-suckle, &c., they are described as French or Italian arbours.”

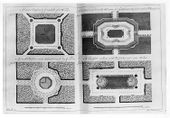

- Anonymous, February 1848, “Hints and Designs for Rustic Buildings” (Horticulturist 2: 363–64)[33]

- “These are the seats, bowers, grottoes and arbors of rustic work—than which nothing can be more easily and economically constructed, nor can add more to the rural or picturesque expression of the scene.

- “Those simple buildings, often constructed only of a few logs and twisted limbs of trees, are in good keeping with the simplest or grandest forms of nature. However wild the scene, wherever the foot-path of the rambler is seen, there the rustic seat is never obtrusive or unmeaning—in the quiet nooks of the garden, amid its flowers and shrubbery, the rustic-covered arbor, partly clothed with climbing plants, is an object of beauty. The terminus of a long walk, otherwise unmeaning, is in no way more easily rendered satisfactory and agreeable, than by a picturesque place of repose.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849: 455–57)[34]

- “The simplest variety of covered architectural seat is the latticed arbor for vines of various descriptions, with the seat underneath the canopy of foliage; this may with more propriety be introduced in various parts of the grounds than any other of its class, as the luxuriance and natural gracefulness of the foliage which covers the arbor, in a great measure destroys or overpowers the expression of its original form. Lattice arbors, however, neatly formed of rough poles and posts, are much more picturesque and suitable for wilder portions of the scenery.

- “There is scarcely a prettier or more pleasant object for the termination of a long walk in the pleasure-grounds or park, than a neatly thatched structure of rustic work, with its seat for repose, and a view of the landscape beyond. On finding such an object, we are never tempted to think that there has been a lavish expenditure to serve a trifling purpose, but are gratified to see the exercise of taste and ingenuity, which completely answers the end in view. . . .

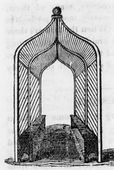

- “Figure 84 is a covered seat or rustic arbor, with a thatched roof of straw. Twelve posts are set securely in the ground, which make the frame of this structure, the openings between being filled in with branches (about three inches in diameter) of different trees—the more irregular the better, so that the perpendicular surface of the exterior and interior is kept nearly equal. In lieu of thatch, the roof may be first tightly boarded, and then a covering of bark or the slabs of trees with the bark on, overlaid and nailed on. The figure represents the structure as formed round a tree. For the sake of variety this might be omitted, the roof formed of an open lattice work of branches like the sides, and the whole covered by a grape, bignonia, or some other vine or creeper of luxuriant growth. The seats are in the interior. . . . [Fig. 10]

- “Those of our readers who may have visited the delightful garden and grounds of M. Parmentier, near Brooklyn, some half a dozen years since . . . will readily remember the rustic prospect-arbor or tower, Fig. 87, which was situated at the extremity of his place. It was one of the first pieces of rustic work of any size, and displaying any ingenuity, that we remember to have seen; and from its summit, though the garden walks afforded no prospect, a beautiful reach of the neighborhood for many miles was enjoyed.” [Fig. 11]

- Elder, Walter, 1849, The Cottage Garden of America (1849: 15–16)[35]

- “LANDLORDS, being generally richer than their tenants, should be first in showing their liberality in endeavours to make their tenants comfortable. They should select healthful sites, and erect neat and convenient houses; with grape-vine arbours attached, so as to reach over and shade the back kitchens.”

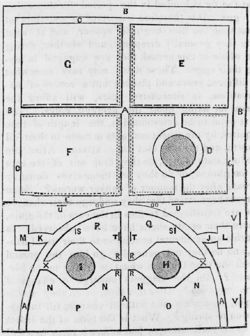

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, February 1849, “Design for a Suburban Garden” (Horticulturist 3: 380)[36]

- “At the end of this wall, we come to the semicircular Italian arbor, D. This arbor, which is very light and pleasing in effect, is constructed of slender posts, rising 8 or 9 feet above the surface, from the tops of which strong transverse strips are nailed, as shown in the plan. The grapes ripen on this kind of Italian arbor much more perfectly than upon one of the common kind, thickly covered with foliage.

- “Beyond this arbor, and at the termination of the central walk, is a vase, rustic basket, or other ornamental object, e. The semi-circle, embraced within the arbor, is a space laid with regular beds.” [Fig. 12]

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1850, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850; repr., 1968: 112–13)[37]

- “In the Design before us. . . there is an air of rustic or rural beauty conferred on the whole cottage by the simple, or veranda-like arbor, or trellis, which runs round three sides of the building; as well as an expression of picturesqueness, by the roof supported on ornamental brackets and casting deep shadows upon the walls.

- “To become aware how much this beauty of expression has to do with rendering this cottage interesting, we have only to imagine it stripped of the arbor-veranda and the projecting eaves, and it becomes in appearance only the most meagre and common-place building, which may be a house or a barn: at the most, it would indicate nothing more by its chimneys and windows, than that it is a human habitation, and not, as at present, that it is the dwelling of a family who have some rural taste, and some love for picturesque character in a house.” [Fig. 13]

Images

Inscribed

J. C. Loudon, “The Italian Arbor” and “The French Arbor,” in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 356, figs. 332 and 333.

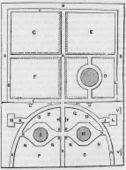

Anonymous, Map of Mr. Andrew Parmentier’s Horticultural & Botanical Garden, at Brooklyn, Long Island, Two Miles From the City of New York, c. 1828. “I. Rustic Arbour.”

Anonymous, “Plan of a Suburban Garden,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 3, no. 8 (February 1849): pl. opp. 353. “Italian arbor, D” on p. 380.

Anonymous, "Plan of a Suburban Garden" [detail], in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 3, no. 8 (February 1849): pl. opp. 353.

Anonymous, “Covered seat or rustic arbor,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 457, fig. 84.

Anonymous, “Rustic Arbours,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 4, no. 7 (January 1850): pl. opp. 297.

Frances Palmer, “Ground Plot of 4-1/4 Acres,” in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), vol. 2, pl. 6. “grape arbor, G.”

Frances Palmer, “Ground Plot,” in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), vol. 2, pl. 29. “N N, grape arbor and trellis.”

Anonymous, “Design for a Cottage for a Country Clergyman,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 6, no. 7 (July 1851): pl. opp. 297. The “Arbour” is located just outside of the Study.

Anonymous, “A Rustic Arbour,” in Louisa Tuthill, History of Architecture (1848), 287, fig. 44.

Associated

Anonymous, “Small Bracketed Cottage,” in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. 78, fig. 9.

Anonymous, “Regular Bracketed Cottage,” in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. 112, figs. 37 and 38.

Anonymous, “Rustic prospect-arbor,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 460, fig. 87.

Attributed

Amy Cox, attr., Box Grove, c. 1800.

John Warner Barber, “Southeastern view of Wesleyan University, Middletown,” in Connecticut Historical Collections (1836), 510.

W. H. Bartlett, “View from Ruggle’s House, Newburgh. (Hudson River),” in Nathaniel Parker Willis, American Scenery (1840), vol. 1, pl. 25.

Anonymous, The Flower-Garden, in Joseph Breck, The Flower-Garden: or, Breck’s Book of Flowers (1841), frontispiece.

Anonymous, “Residence of Mr. D. Barnes, Middletown, CT,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 6, no. 4 (April 1851): pl. opp. 153.

A Religious Encampment in the Wilderness, December 30, 1865.

Notes

- ↑ Noah Webster, in his American Dictionary of the English Language (1828), defined a pergola as an Italian-derived word meaning “a kind of arbor.” In our study, however, no usage examples of pergola were identified before 1850, suggesting that this term was not a common one for arbor. By 1848, in a reprint of the dictionary, Webster offered a different definition of pergola that suggests that the term was still relatively obscure. Pergola was then defined as “a sort of gallery or balcony in a garden, or a terrace overhanging one” found in “ancient architecture.” view on Zotero.

- ↑ This second form was quite prevalent in British treatises. In 1799 Charles Marshall equated arbors with summerhouses; this definition was continued in G. Gregory’s A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1816) and elaborated by the garden writers J. C. Loudon (1826), George William Johnson, and Jane Loudon (1845), all of whom stipulated that an arbor was a seat, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Warren M. Billings, ed., The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century: A Documentary History of Virginia, 1606–1689 (Williamsburg: Institute of Early American History and Culture at Williamsburg, Virginia, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Louis B. Wright and Virginia Freund, eds., The Historie of Travell into Virginia Britania (1612) (Nendeln and Liechtenstein: Kraus, 1967), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Honyman, Colonial Panorama 1775: Dr. Robert Honyman’s Journal for March and April, ed. Philip Padelford (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1939), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Manasseh Cutler, Life, Journals and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D., ed. William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkin Cutler, 2 vols. (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1888), vol. 1, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constantia [Judith Sargent Murray], “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania,” Massachusetts Magazine, or, Monthly Museum of Knowledge and Rational Entertainment 7, no. 3 (July 1791): 413–17, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fiske Kimball, Mr. Samuel McIntire, Carver, the Architect of Salem (Portland, ME: Southworth-Anthoensen, 1940), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Parmentier’s Horticultural Garden,” New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal 7, no. 11 (October 3, 1828): 84–85, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Silk Buckingham, The Eastern and Western States of America, 3 vols. (London: Fisher, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Boyd, A History of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1827–1927 (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1929), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “A Few Words on Rustic Arbours,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 4, no. 7 (January 1850): 320–21, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constance Greiff, John Notman, Architect, 1810–1865 (Philadelphia: Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1979), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629; repr., Norwood, NJ: W. J. Johnson, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia: Or, An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 2 vols. (London: J. and J. Knapton, J. Darby, D. Midwinter, et al., 1741–43), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Philip Miller, The Gardeners Dictionary: Containing the Methods of Cultivation and Improving the Kitchen, Fruit, and Flower Garden. As Also, the Physick Garden, Wilderness, Conservatory, and Vineyard. . . , 7th ed. (London: Philip Miller, 1759), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas A. Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews. . . , 5th ed. (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Marshall, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening, 1st American ed., 2 vols. (Boston: Samuel Etheridge, 1799), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Fessenden, ed., The New American Gardener (Boston: J. B. Russell, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James E. Teschemacher, “Extracts from Foreign Publications,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener's Magazine 1 (August 1, 1835): 304–9, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James E. Teschemacher, “On Horticultural Architecture,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 1 (November 1, 1835): 409–12, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Sayers, “On Laying out Gardens and Ornamental Plantations,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener's Magazine 3 (November 1, 1837): 409–11, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Sayers, The American Flower Garden Companion, Adapted to the Northern States (Boston: Joseph Breck and Company, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Walsh, “Remarks on Ornamental Gardening, With a Plan of a Fruit, Flower and Vegetable Garden,” New England Farmer, and Horticultural Register 19, no. 39 (March 31, 1841): 308–9, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden, ed. A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845), on Zotero.

- ↑ Rusticus [pseud.], “Design for a Rustic Gate,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 1, no. 2 (August 1846): 72–73, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Hints and Designs for Rustic Buildings,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 2, no. 8 (February 1848): 363–65, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America. . . , 4th ed. (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter Elder, The Cottage Garden of America (Philadelphia: Moss, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “Design for a Suburban Garden,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 8 (February 1849): 380, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses; Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-Houses, and Villas (New York: D. Appleton, 1850; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1968), view on Zotero.