Grotto

History

The term grotto was applied to a cave or cavern made by hollowing out the ground, as at The Woodlands, or digging into a bank or hillside, as at Lemon Hill and Monticello. While some grottoes were formed out of a naturally occurring cavity or depression—as in the case of the grotto at Belfield—they could also be created artificially, complete with contiguous artificial rockwork [Fig. 1] or constructed simply as a stone summerhouse. They could also be made from a combination of natural and artificial elements. In 1771, for example, Thomas Jefferson described building up a natural cave with rock or clay, then covering it with moss or thatch (view citation).

A general characteristic of the grotto was its ornamentation or embellishment with shells, rocks, and bits of glass or, as Richard Stockton wrote in 1767, curious “antiquities.” His wife, Annis Boudinot Stockton, planned her shell grotto at Morven, near Princeton, as a museum for the display of such ancient relics. Not only did Stockton visit Alexander Pope’s garden in Twickenham, near London, which was well known for its extensive shell-covered interior, but he also collected several souvenirs, including a piece of Roman brick from Dover Castle, a piece of wood from the King’s Coronation chair, and other curiosities for this grotto.[1]

In his dictionary, G. (George) Gregory repeats Ephraim Chambers’s definition of the grotto as an ornamented cave, adding the recipe for cement that would secure the placement of shells, fossils, crystalline minerals, and curious stones (view citation). This recipe also would render the grotto waterproof. Water was a key element in the creation of the grotto, whether it ran through the grotto as a stream or was available from a nearby spring. Accounts document that the sound and dampness of water were essential to the experience of the grotto.

Grottoes were sited at the termination of walks, as recommended by Bernard M’Mahon (view citation), or in secluded parts of the garden as were the grottoes at Economy and Andalusia, Pennsylvania. [Fig. 2]. They were sometimes built under another structure such as a summerhouse or a glasshouse—as at Belfield—or as an enhancement to a spring or ice house [Fig. 3]. The reports of visitors echo the experience of an enchanted, unearthly ambience in the grotto, invoking its association with the underworld and fantasy. The grotto’s “veiled entrance with tracery of creepers,” and its interior “cool with greenish-light,” suggested links to the mythological tradition of an underworld deriving from classical precedents or caves as sites for mysteries and transformations.[2]

—Therese O’Malley

Texts

Usage

- Stockton, Richard, July 1767, in a letter to Annis Boudinot Stockton, describing England (quoted in Greiff 1989: 1:38) [3]

- “England is not the place for curious shells, therefore you must not expect much by me in that way; but I shall bring you a piece of Roman brick, which I knocked off the top of Dover Castle, which is said to have been built before the death of Christ. I have also got for your collection a piece of wood, which I cut off the effigy of Archbishop Peckham, buried in the Cathedral of Canterbury more than five hundred years ago; likewise a piece from the king’s coronation chair, and several other things, which merely as antiquities, may deserve a place in your grotto.

- “I have dined with Mr. Neat several times. Miss Neat is exceedingly obliged for the shells you sent her. She has made some curious flowers out of them. She and her mamma are both engaged to find out for me the best cement for sticking shells in the large way, which I know will be needful for you when you begin your grotto. You see I do not omit attending to your commands. I told you in my last that I intended a visit to Twickenham, to see Mr. Pope’s house, gardens, and grotto, for you direction. This I shall execute if it please God.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1771, describing plans for Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1944: 26–27),[4] back up to history

- “. . . the ground above the spring being very steep, dig into the hill and form a cave or grotto. build up the sides and arch with stiff clay. cover this with moss. spangle it with translucent pebbles from Hanovertown, and beautiful shells from the shore at Burwell’s ferry. pave the floor with pebbles. let the spring enter at a corner of the grotto, pretty high up the side, and trickle down, or fall by a spout into a basin, from which it may pass off through the grotto. the figure will be better placed in this. form a couch of moss. the English inscription will then be proper.

- Nymph of the grot, these sacred springs I keep,

- And to the murmur of these waters sleep;

- Ah! spare my slumbers! gently tread the cave!

- And drink in silence, or in silence lave!”

- Quincy, Josiah, May 3, 1773, describing the country seat of John Dickinsen, near Philadelphia, PA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “This worthy and arch-politician, (for such he is though his views and disposition lead him to refuse the latter appellation) here enjoys otium cum dignitate as much as any man. Take into consideration the antique look of his house, his gardens, green-house, bathing-house, grotto, study, fish-pond, fields, meadows, vista, through which is distant prospect of Delaware River.”

- Anonymous, 1783, describing the gardens at Stowe, estate of George Grenville Nugent Temple, England (quoted in O’Neal 1976: 337) [5]

- “[The grotto] stands at the Head of the Serpentine River, and on each side a Pavilion, the one ornamented with Shells, the other with Pebbles and Flints broke to Pieces. The Grotto is furnished with a great number of Looking-glasses both on the Walls and Ceiling, all in Frames of Plaster-work, set with Shells and Flints. A Marble Statue of Venus, on a Pedestal stuck with the same.” [Fig. 4]

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1786, “Memorandums Made on a Tour to Some of the Gardens in England” (quoted in Hunt and Willis, eds., 1975: 333)[6]

- “Twickenham . . . the grotto is under the street, and goes out level to the water. . . .

- “Paynshill . . . well described by Whateley. Grotto said to have cost 7000.£.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 14, 1787, describing the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, vicinity of Philadelphia, PA (1987: 1:277)[7]

- “There were several other hermitages, constructed in different forms; but the Grottoes and Hermitages were not yet completed, and some space of time will be necessary to give them that highly romantic air which they are capable of attaining.”

- G., L., June 15, 1788, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (Madsen 1988: B2)[8]

- “. . . a little further on, you come to a charming spring, some part of the ground is hollowed out where Mr Hamilton is going to form a grotto, he has already collected some shells.”

- Anonymous, 1797, describing the gardens at Stowe, estate of George Grenville Nugent Temple, England (quoted in O’Neal 1976: 337)[5]

- “[The Grotto has] trees which stretch across the water, together with those which back it, and others which hang over the cavern, form[ing] a scene singularly perfect in its kind. . . . In the upper [end] is placed a fine marble statue of VENUS rising from her bath, and from this the water falls into the lower bason.” [Fig. 5]

- Wailes, Benjamin L. C., December 29, 1829, describing Lemon Hill, estate of Henry Pratt, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Moore 1954: 359) [9]

- “But the most enchanting prospect is towards the grand pleasure grove & green house of a Mr. Prat[t], a gentleman of fortune, and to this we next proceeded by a circutous [sic] rout, passing in view of the fish ponds, bowers, rustic retreats, summer houses, fountains, grotto, &c., &c. The grotto is dug in a bank [and] is of a circular form, the side built up of rock and arched over head, and a number of Shells [?]. A dog of natural size carved out of marble sits just within the entrance, the guardian of the place. A narrow aperture lined with a hedge of arbor vitae leads to it. Next is a round fish pond with a small fountain playing in the pond.”

- Kennedy, John Pendleton, 1833, in an address to the Horticultural Society of Maryland, describing the flower hall of the First Annual Exhibition (1833: 6)[10]

- “. . . this hall has been transmuted into a charmed grotto, where one might fancy some unearthly enchanter had wrought his spell to delight the senses with all the riches of shape, hue and fragrance.”

- Martineau, Harriet, May 4, 1835, describing New Orleans, LA (1838: 1:274)[11]

- “All the rest [of the villas] were an entertainment to the eye as they stood, white and cool, amid their flowering magnolias, and their blossoming alleys, hedges, and thickets of roses. In returning [from the battle-ground], we alighted at one of these delicious retreats, and wandered about, losing each other among the thorns, the ceringas, and the wilderness of shrubs. We met in a grotto, under the summer-house, cool with a greenish light, and veiled at its entrance with a tracery of creepers. There we lingered, amid singing or silent dreaming. There seemed to be too little that was real about the place for ordinary voices to be heard speaking about ordinary things.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), September 1840, describing the estate of James Arnold, New Bedford, MA (Magazine of Horticulture 6: 364)[12]

- “Continuing through the winding walks, shady bowers, and umbrageous retreats, through which rustic seats were placed, we arrived at the shell grotto. This is an ingenious piece of work, finely executed under the direction of Mr. Arnold. The roof is supported by columns of rough trunks of trees, the outer part of the roof thatched, and the ceiling elegantly inlaid with shells, quartz, &c. A rustic sofa and table are the only articles in the interior. So secluded is this grotto, that the robin has built its nest and reared its young in some of the niches left for that purpose.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1850, describing Lemon Hill, estate of Henry Pratt, Philadelphia, PA (1850: 331)[13]

- “850. Lemon Hill, near Philadelphia. . . . [Downing observes:] '. . . An extensive range of hothouses, curious grottoes and spring-houses, as well as every other gardenesque structure, gave variety and interest to this celebrated spot, which we regret the rapidly extending trees, and the mania for improvement there, as in some of our other cities, have now nearly destroyed and obliterated.' (Downing’s Landscape Gardening adapted to North America.)”

Citations

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741, Cyclopaedia (1741: 1:n.p.)[14]

- “GROTTO*, or GROTTA, in natural history, a large deep cavern or den in a mountain or rock. . . .

- “GROTTO, is also used for a little artificial edifice made in a garden, in imitation of a natural grotto. The outsides of these grotto’s are usually adorned with rustic architecture, and their inside with shell-work, furnished like-wise with various jet-d'eaus, or fountains, &c.

- “The grotto at Versailles is an excellent piece of building.—Solomon de Caux has an express treatise of grotto’s and fountains.

- “* The word is Italian, grotta, formed according to Menage, and &c. from the Latin crypta: du Cange observes, that grotta was used in the same sense in the corrupt Latin.”

- Anonymous, 1752, South Carolina Gazette (quoted in Lounsbury, ed., 1994: 62)[15]

- “To Gentlemen . . . as have a taste in pleasure . . . gardens . . . may depend on having them laid out, leveled, and drained in the most compleat manner, and politest taste, by the subscriber; who perfectly understands . . . erecting water works . . . fountains, cascades, grottos.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 1:n.p.)[16]

- “GRO'TTO. n.s. [grotte, French, grotta, Italian.] A cavern or cave made for coolness. It is not used properly of a dark horrid cavern.”

- Heely, Joseph, 1777, Letters on the Beauties of Hagley, Envil, and the Leasowes (1777; repr., 1982: 1:55–58)[17]

- “Beauty in gardening, as I observed before, does not consist in perfect symmetry, as in architecture; it is composed, and ever delights, in a sympathizing irregularity. . . .

- “This is the grand chain on which the principles of modern gardening depend; and what should never be out of the eye of the designer: if one link be broken in the most insignificant object, it is of such consequence, that the whole may fall into censure, and other parts be sullied by its deformity.

- “The artist who deviates not from these rules, will know that an obelisk best becomes a hill . . . gots [grottoes, sic], contemplative and retired, down in the most sombrous obscurity, near the dribbling of rills. . . .

- “You will conclude that great expences must consequently attend the performance of a gay, modern design.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (1806: 58, 64–65)[18] back up to history

- “In various parts of the pleasure-ground, leave recesses and other places surrounded with clumps of trees and shrubs, for the erection of garden edifices, such as temples, grottos, rural seats, statues, &c. . . .

- “In some spacious pleasure-grounds various light ornamental buildings and erections are introduced, as ornaments to particular departments; such as temples, bowers, banquetting houses, alcoves, grottos, rural seats, cottages, fountains, obelisks, statues, and other edifices; these and the like are usually erected in the different parts, in openings between the divisions of the ground, and contiguous to the terminations of grand walks, &c. . . .

- “Likewise in some parts are exhibited artificial rock-work, contiguous to some grotto, fountain, rural piece of water, &c. and planted with a variety of saxatile plants, or such as grow naturally on rocks and mountains.”

- Gregory, G. (George), 1816, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1816: 2:n.p.),[19] back up to history

- “GROTTO is also used for a little artificial edifice made in a garden, in imitation of a natural grotto. The outside of these grottos are usually adorned with rustic architecture, and their inside with shell-work, fossils, &c. finished likewise with jets-d'eau or fountains, &c. A cement for artificial grottos may be made thus: Take two parts of white rosin, melt it clear, and add to it four parts of bees'-wax; when melted together, add two or three parts of the powder of the stone you design to cement, or so much as will give the cement the colour of the stone. With this cement, the stone, shells, &c. after being well dried before the fire, may be cemented. Artificial red coral branches, for the embellishment of grottos, may be made in the following manner: Take clear rosin, dissolve it in a brass-pan, to every ounce of which add two drams of the finest vermilion; when you have stirred them well together, and have chosen your twigs and branches, peeled and dried, take a pencil and paint the branches all over whilst the composition is warm; afterwards shape them in imitation of natural coral. This done, hold the branches over a gentle coal-fire, till all is smooth and even as if polished. In the same manner white coral may be prepared with white lead, and black coral with lamp-black. A grotto may be built with little expense, of glass, cinders, pebbles, pieces of large flint, shells, moss, stones, counterfeit coral, pieces of chalk, &c. all bound or cemented together with the above-described cement.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 356) [20]

- “1815. Grottoes are resting-places in recluse situations, rudely covered externally, and within finished with shells, corals, spars, crystallisations, and other marine and mineral productions, according to fancy. To add to the effect, pieces of looking-glass are inserted in different places and positions.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 1:n.p.)[21]

- “GROT, GROT'TO, n. [Fr. grotte, It. grotta, Sp. and Port. gruta; G. and Dan. grotte; D. grot; Sax. grut. Grotta is not used.]

- “1. A large cave or den; a subterraneous cavern, and primarily, a natural cave or rent in the earth, or such as is formed by a current of water, or an earthquake. Pope. Prior. Dryden.

- “2. A cave for coolness and refreshment.”

- Loudon, Jane, 1845, Gardening for Ladies (1845: 239)[22]

- “GROTTOES are covered seats, or small cells or caves, with the sides and roof constructed of rockwork, or of brick or stone, covered internally with spar or other curious stones, and sometimes ornamented with marine productions, such as corals, madrepores, or shells. A kind of grotto is also constructed of roots ornamented with moss. Perhaps the most generally effective grotto is one formed with blocks of stone, without ornaments either externally or internally, with the floor paved with pebbles, and with a large long stone, or a wooden bench painted to imitate stone, as a seat. The roof should be rendered waterproof by means of cement, and covered with ivy; or a mass of earth may be heaped over it, and planted with periwinkle, ivy, or other low-growing evergreen shrubs, which may be trained to hang down over the mouth of the grotto. In some cases it answers to cover grottoes with turf, so that when seen from behind they appear like a knoll of earth, and in front like the entrance into a natural cave. As grottoes are generally damp at most seasons of the year, they are more objects of ornament or curiousity than useful as seats or places of repose. One of the finest grottoes in England is that at Pain’s Hill, formed of blocks of stone, with stalactite incrustations hanging from the roof, and a small stream running across the floor. Pope’s grotto at Twickenham, the grotto at Weybridge, and that at Wimbourne St Giles, which last cost 10,000l., are also celebrated. A fountain or gushing stream is a very appropriate ornament to a grotto; though, where practicable, it is better in an adjoining cave, when a person sitting in the grotto can hear the murmur of the water, and see the light reflected on it at a distance, than in the grotto itself.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 276)[23]

- “GROTTO, is a resting place, formed rudely of rock-work, roots of trees, and shells, and is most appropriately placed beneath the deep shade of woods, and on the margin of water. Its intention is to be a cool retreat during summer.”

- Tuthill, Louisa C., 1848, History of Architecture (1848: 394)[24]

- “Grotto. An artificial cave.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849: 473)[25]

- “Unity of expression is the maxim and guide in this department of the art, as in every other. . . .

- “With regard to pavilions, summer-houses, rustic seats, and garden edifices of like character, they should, if possible, in all cases be introduced where they are manifestly appropriate or in harmony with the scene. Thus a grotto should not be formed in the side of an open bank, but in a deep shadowy recess.”

Images

Inscribed

J. C. Loudon, A grotto scene from Monza, Italy, in An Encyclopedia of Gardening (1834), 36, fig. 20.

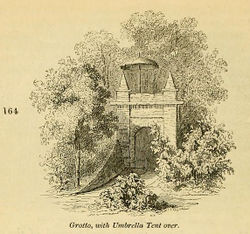

J. C. Loudon, “Grotto, with Umbrella Tent over,” Cheshunt Cottage, in The Gardener’s Magazine 15, no. 117 (December 1839): 654, fig. 164.

Attributed

Charles Willson Peale, View of the garden at Belfield, 1816.

Notes

- ↑ Karen Bescherer Metheny et al., “Method in Landscape Archaeology: Research Strategies in a Historic New Jersey Garden,” in Landscape Archaeology: Reading and Interpreting the American Historical Landscape, ed. Rebecca Yamin and Karen Bescherer Metheny (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1996), 8, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Naomi Miller, Heavenly Caves: Reflections on the Garden Grotto (New York: G. Braziller, 1982), 11–12, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constance Greiff, “Morven: A Documentary History” (Hopewell, NJ: Heritage Studies, 1989), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 William Bainter O’Neal, Jefferson’s Fine Arts Library: His Selections for the University of Virginia Together with His Own Architectural Books (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Dixon Hunt and Peter Willis, eds., The Genius of Place: The English Landscape Garden, 1620–1820 (London: Paul Elek, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Parker Cutler, Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D. (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Karen Madsen, “William Hamilton’s Woodlands,” (paper presented for seminar in American Landscape, 1790–1900, instructed by E. McPeck, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Hebron Moore, “A View of Philadelphia in 1829: Selections from the Journal of B. L. C. Wailes of Natchez,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 78 (July 1954): 353–60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Pendleton Kennedy, Address Delivered before the Horticultural Society of Maryland at Its First Annual Exhibition, June 12, 1833 (Baltimore, MD: John D. Toy, 1833), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Harriet Martineau, Retrospect of Western Travel, 2 vols. (London: Saunders and Otley, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes on Gardens and Gardening, in New Bedford, Mass.,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 6, no. 10 (October 1840): 361–66, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed. (London: Longman et al., 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . ., 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter: 1741–43), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Heely, Letters on the Beauties of Hagley, Envil, and the Leasowes, 2 vols. (1777; repr., New York: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M’Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done . . . for Every Month of the Year. . . . (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Gregory, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 1st American ed., 3 vols. (Philadelphia: Isaac Peirce, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden, ed. A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Louisa C. Tuthill, History of Architecture, from the Earliest Times . . . (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1848), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening . . . 4th ed. (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1849), view on Zotero.