Difference between revisions of "Alexander Jackson Davis"

m (→History) |

m (→History) |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

<span id="RuralResidences_cite"></span>With Donaldson’s support and encouragement, Davis began work on a book composed of architectural drawings and plans accompanied by short explanatory texts ([[#RuralResidences|view text]]). In 1837, Davis published this work, ''Rural Residences, Etc. Consisting of Designs, Original and Selected, for Cottages, Farm-Houses, Villas, and Village Churches: With Brief Explanations, Estimates, and a Specification of Materials, Construction, Etc.'', in periodical installments each containing four designs. The concept and format seem to have been modeled on the British architect and artist John Buonarotti Papworth's 1818 publication with the strikingly similar title ''Rural Residences, Consisting of a Series of Designs for Cottages, Decorated Cottages, Small Villas, and Other Ornamental Buildings.'' As in Papworth's work, the floorplans within Davis's ''Rural Residences'' do not extend to the surrounding landscape, but the perspectival drawings suggest complementary planting designs. Davis’s brief introduction emphasizes the landscape as a design factor in terms of the “connexion [of a building] with its site.”<ref>Alexander Jackson Davis, ''Rural Residences, Etc. Consisting of Designs, Original and Selected, for Cottages, Farm-Houses, Villas, and Village Churches: With Brief Explanations, Estimates, and a Specification of Materials, Construction, Etc.'' (New York, 1837), n.p., [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/LDE2TS2Z view on Zotero].</ref> | <span id="RuralResidences_cite"></span>With Donaldson’s support and encouragement, Davis began work on a book composed of architectural drawings and plans accompanied by short explanatory texts ([[#RuralResidences|view text]]). In 1837, Davis published this work, ''Rural Residences, Etc. Consisting of Designs, Original and Selected, for Cottages, Farm-Houses, Villas, and Village Churches: With Brief Explanations, Estimates, and a Specification of Materials, Construction, Etc.'', in periodical installments each containing four designs. The concept and format seem to have been modeled on the British architect and artist John Buonarotti Papworth's 1818 publication with the strikingly similar title ''Rural Residences, Consisting of a Series of Designs for Cottages, Decorated Cottages, Small Villas, and Other Ornamental Buildings.'' As in Papworth's work, the floorplans within Davis's ''Rural Residences'' do not extend to the surrounding landscape, but the perspectival drawings suggest complementary planting designs. Davis’s brief introduction emphasizes the landscape as a design factor in terms of the “connexion [of a building] with its site.”<ref>Alexander Jackson Davis, ''Rural Residences, Etc. Consisting of Designs, Original and Selected, for Cottages, Farm-Houses, Villas, and Village Churches: With Brief Explanations, Estimates, and a Specification of Materials, Construction, Etc.'' (New York, 1837), n.p., [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/LDE2TS2Z view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

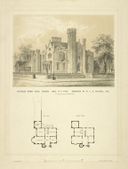

| − | [[File:2208.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 6, ]] | + | [[File:2208.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 6, E. Jones, F. [Fanny] Palmer, and E. Palmer (lithographers), Alexander Jackson Davis (architect), ''Suburban Gothic Villa, Murray Hill, N.Y. City. Residence of W. C. Waddell, Esq. 5th Avenue, Between 37 & 38th Street. Below, Plans of First and Second Floors'', n.d.]] |

<span id="Introduction_cite"></span>Donaldson introduced Davis to the nurseryman and landscape gardener [[Andrew Jackson Downing]] in 1838 ([[#Introduction|view text]]), and Davis would go on to design [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing’s]] own Hudson River estate Highland Park (1838–1839).<ref>Patrick Alexander Snadon, “A. J. Davis and the Gothic Revival Castle in America, 1832-1865” (Ph.D., Cornell University, 1988), 173, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> Between 1839 and 1850, [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing]] used woodcuts of designs and sketches by Davis to illustrate many of his publications, including ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (first published in 1841), ''The Architecture of Country Houses'' (1850), and ''The Horticulturist''. The publicity generated by these works made Davis one of the most desirable architects for wealthy owners of rural estates and [[plantation]]s. Donaldson was also instrumental in helping Davis obtain commissions for campus designs, including the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, writing in 1843 that <span id="Recommendation_cite"></span>“Mr Davis is the readiest & most skillful draughtsman that I know, and can furnish you with designs for Exterior Elevations or Interior Decorations—plans for [[Gate]]s, [[Fence]]s, & improving grounds about Buildings—in fact the danger is, when he mounts the Pegasus of Design, he may require the restraining taste of another” ([[#Recommendation|view text]]). | <span id="Introduction_cite"></span>Donaldson introduced Davis to the nurseryman and landscape gardener [[Andrew Jackson Downing]] in 1838 ([[#Introduction|view text]]), and Davis would go on to design [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing’s]] own Hudson River estate Highland Park (1838–1839).<ref>Patrick Alexander Snadon, “A. J. Davis and the Gothic Revival Castle in America, 1832-1865” (Ph.D., Cornell University, 1988), 173, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> Between 1839 and 1850, [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing]] used woodcuts of designs and sketches by Davis to illustrate many of his publications, including ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (first published in 1841), ''The Architecture of Country Houses'' (1850), and ''The Horticulturist''. The publicity generated by these works made Davis one of the most desirable architects for wealthy owners of rural estates and [[plantation]]s. Donaldson was also instrumental in helping Davis obtain commissions for campus designs, including the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, writing in 1843 that <span id="Recommendation_cite"></span>“Mr Davis is the readiest & most skillful draughtsman that I know, and can furnish you with designs for Exterior Elevations or Interior Decorations—plans for [[Gate]]s, [[Fence]]s, & improving grounds about Buildings—in fact the danger is, when he mounts the Pegasus of Design, he may require the restraining taste of another” ([[#Recommendation|view text]]). | ||

| − | [[File:0956.jpg|thumb|Fig. 7, ]] | + | [[File:0956.jpg|thumb|Fig. 7, Alexander Jackson Davis, Canopied pavilion at Blithewood, 1836.]] |

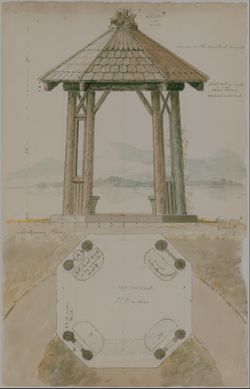

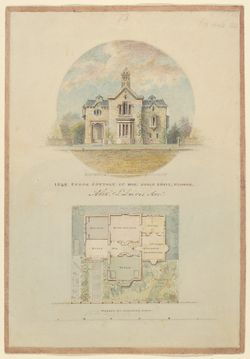

In his publications and his flourishing practice throughout the 1840s, Davis developed two main types of residential structures: large, asymmetrical villas for wealthy clients characterized by two main wings in an L-shaped configuration, and smaller rectangular cottages intended for clients of more modest means.<ref>For a discussion of the villa designs, which employed massing and decorative elements to emphasize “river-front” and “road front” facades, see Snadon 1988, 81–82, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> <span id="#Villa_cite"></span>Both types featured a [[veranda]] or [[porch]] wrapped around the building, which connected the house to its immediate surroundings, while his villas often incorporated “[[prospect tower]]s” or “prospect rooms” that provided sweeping views of the landscape, as seen in his design for Murray Hill ([[#Villa|view text]]) [Fig. 6].<ref>Snadon 1988, 73 (belvederes), 75 (verandas), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> Davis also designed many small, free-standing structures for contemplating the landscape, including tented seats [Fig. 7], and [[summerhouse]]s [Fig. 8], inspired by the publications of [[John Claudius Loudon|J. C. Loudon]] and Batty Langley.<ref>Snadon 1988, 80, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing’s]] publications further emphasized the visual relationship between Davis’s designs and the surrounding landscape, recommending paint colors that harmonized with green foliage. | In his publications and his flourishing practice throughout the 1840s, Davis developed two main types of residential structures: large, asymmetrical villas for wealthy clients characterized by two main wings in an L-shaped configuration, and smaller rectangular cottages intended for clients of more modest means.<ref>For a discussion of the villa designs, which employed massing and decorative elements to emphasize “river-front” and “road front” facades, see Snadon 1988, 81–82, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> <span id="#Villa_cite"></span>Both types featured a [[veranda]] or [[porch]] wrapped around the building, which connected the house to its immediate surroundings, while his villas often incorporated “[[prospect tower]]s” or “prospect rooms” that provided sweeping views of the landscape, as seen in his design for Murray Hill ([[#Villa|view text]]) [Fig. 6].<ref>Snadon 1988, 73 (belvederes), 75 (verandas), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> Davis also designed many small, free-standing structures for contemplating the landscape, including tented seats [Fig. 7], and [[summerhouse]]s [Fig. 8], inspired by the publications of [[John Claudius Loudon|J. C. Loudon]] and Batty Langley.<ref>Snadon 1988, 80, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing’s]] publications further emphasized the visual relationship between Davis’s designs and the surrounding landscape, recommending paint colors that harmonized with green foliage. | ||

| − | [[File:0854.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 8, ]] | + | [[File:0854.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 8, Alexander Jackson Davis, Shore Seat for Montgomery Place, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York (elevation and plan), 1870–79.]] |

In addition to his clients in the New York area, Davis found patronage among several owners of [[plantation]]s in the American south. These commissions reveal how Davis, like other architects of the era, adapted the [[picturesque]] to aestheticize or obscure built landscapes of slavery.<ref>See also the work of William Birch for Rosalie Stier Calvert at Riversdale, mentioned in Therese O’Malley, “‘Models in This Art’: Tracing the Brownian Landscape Tradition in America,” ''Garden History'' 44, no. Suppl. 1 (Autumn 2016): 78–79, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/RUA439AW view on Zotero].</ref> With a workforce of more than 500 people, Philip St. George Cocke’s Belmead Plantation (1845–1848), near Powhatan, Virginia, was comparable in scale to large southern [[plantation]]s, such as Daniel and Martha Turnbull’s [[Rosedown Plantation]] (1835–1845) in Louisiana.<ref>Daniel Bluestone, “A. J. Davis’s Belmead: Picturesque Aesthetics in the Land of Slavery,” ''Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians'' 71, no. 2 (2012): 147, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/FM7YPU9N view on Zotero].</ref> At Belmead, Davis and Cocke modified [[picturesque]] designs for cottages and gatehouses to function as slave [[quarter]]s. Architectural decorations featured heraldic depictions of cotton, tobacco, wheat, and corn that brought the landscape into the main house, but elided the bodies of the enslaved people who cultivated them.<ref>Snadon 1988, 201, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> Architectural historian Daniel Bluestone has shown that much of the construction labor at Belmead was carried out by enslaved people, and argued that Davis’s designs for the estate hid slavery behind a [[picturesque]] veneer connoting refinement and taste. At Loudoun Plantation near Lexington, Kentucky (1849–1852), Davis accommodated his client Francis Key Hunt’s requests to eliminate prominent windows from the northeast face of his residence, overlooking the “private [[yard]]” in which his enslaved African American servants lived and worked.<ref>Patrick Snadon, “Loudoun: Two New York Architects and a Gothic Revival Villa in Antebellum Kentucky,” The Kentucky Review 9, no. 3 (October 1, 1989): 68–72, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/BIK2NNHX view on Zotero].</ref> Whether by altering the designs of slave [[quarter]]s at Belmead or the main [[plantation]] house at Loudoun, Davis used [[picturesque]] designs to indulge the ideological blindspots of these clients. | In addition to his clients in the New York area, Davis found patronage among several owners of [[plantation]]s in the American south. These commissions reveal how Davis, like other architects of the era, adapted the [[picturesque]] to aestheticize or obscure built landscapes of slavery.<ref>See also the work of William Birch for Rosalie Stier Calvert at Riversdale, mentioned in Therese O’Malley, “‘Models in This Art’: Tracing the Brownian Landscape Tradition in America,” ''Garden History'' 44, no. Suppl. 1 (Autumn 2016): 78–79, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/RUA439AW view on Zotero].</ref> With a workforce of more than 500 people, Philip St. George Cocke’s Belmead Plantation (1845–1848), near Powhatan, Virginia, was comparable in scale to large southern [[plantation]]s, such as Daniel and Martha Turnbull’s [[Rosedown Plantation]] (1835–1845) in Louisiana.<ref>Daniel Bluestone, “A. J. Davis’s Belmead: Picturesque Aesthetics in the Land of Slavery,” ''Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians'' 71, no. 2 (2012): 147, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/FM7YPU9N view on Zotero].</ref> At Belmead, Davis and Cocke modified [[picturesque]] designs for cottages and gatehouses to function as slave [[quarter]]s. Architectural decorations featured heraldic depictions of cotton, tobacco, wheat, and corn that brought the landscape into the main house, but elided the bodies of the enslaved people who cultivated them.<ref>Snadon 1988, 201, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> Architectural historian Daniel Bluestone has shown that much of the construction labor at Belmead was carried out by enslaved people, and argued that Davis’s designs for the estate hid slavery behind a [[picturesque]] veneer connoting refinement and taste. At Loudoun Plantation near Lexington, Kentucky (1849–1852), Davis accommodated his client Francis Key Hunt’s requests to eliminate prominent windows from the northeast face of his residence, overlooking the “private [[yard]]” in which his enslaved African American servants lived and worked.<ref>Patrick Snadon, “Loudoun: Two New York Architects and a Gothic Revival Villa in Antebellum Kentucky,” The Kentucky Review 9, no. 3 (October 1, 1989): 68–72, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/BIK2NNHX view on Zotero].</ref> Whether by altering the designs of slave [[quarter]]s at Belmead or the main [[plantation]] house at Loudoun, Davis used [[picturesque]] designs to indulge the ideological blindspots of these clients. | ||

| − | [[File:1928.jpg|thumb|Fig. 9, ]] | + | [[File:1928.jpg|thumb|Fig. 9, Alexander Jackson Davis, Map of Blithewood, c. 1840s.]] |

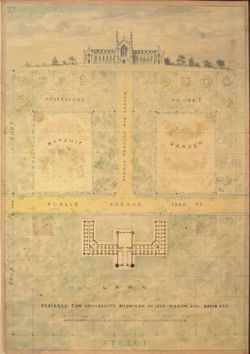

<span id="#Advertisement_cite"></span> In addition to marketing himself as an architect, Davis also advertised his ability to create designs and plans for “[[landscape gardening]]” ([[#Advertisement|view text]]). Several of Davis’s site plans for villas and universities survive. His most comprehensive residential site plan, made for [[Blithewood]] [Fig. 9], is labelled with a variety of features including a boathouse on the river, a [[Rustic style|rustic]] tent, a [[Cascade/Cataract/Waterfall|cataract]], a barn, a grass field, and two springs. Davis provided a variety of [[landscape gardening]] services to his clients, producing a site plan for Glen Ellen (now lost), recommending books on the subject to George Merritt for his estate Lyndhurst, and meeting with Cocke to discuss planting at Belmead.<ref>Susanne Brendel-Pandich, “From Cottages to Castles: The Country House Designs of Alexander Jackson Davis,” in ''Alexander Jackson Davis, American Architect, 1803-1892'', ed. Amelia Peck (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rizzoli, 1992), 60 (book recommendations for Merritt), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/WLVSXGXF view on Zotero]; Snadon 1988, 98 (lost Glen Ellen site plan), 208-209 (visit to Belmead to discuss planting), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> Even his more modest residential floorplans sometimes indicated landscape elements such as [[Terrace/Slope|terraces]], [[walk]]s, [[drive]]s, [[shrubbery]], grass, and plants, as in the 1849 drawings for his mother Julia Jackson Davis’s Kirri Cottage [Fig. 10]. Davis’s university campus proposals reveal a consistent approach to institutional landscapes, recognizing not only the aesthetic but also the educational and practical functions of gardens, [[lawn]]s, and [[walk]]s. His 1838 plan for the University of Michigan features two square [[botanic garden]]s filled with geometric [[bed]]s arranged around oval [[fountain]]s, divided by a tree-lined [[avenue]] [Fig. 11]. His later design for the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, (1850–1858) likewise emphasizes a tree-lined [[avenue]], but asymmetrically locates both sections of the [[botanic garden]]s on the east edge of the campus. | <span id="#Advertisement_cite"></span> In addition to marketing himself as an architect, Davis also advertised his ability to create designs and plans for “[[landscape gardening]]” ([[#Advertisement|view text]]). Several of Davis’s site plans for villas and universities survive. His most comprehensive residential site plan, made for [[Blithewood]] [Fig. 9], is labelled with a variety of features including a boathouse on the river, a [[Rustic style|rustic]] tent, a [[Cascade/Cataract/Waterfall|cataract]], a barn, a grass field, and two springs. Davis provided a variety of [[landscape gardening]] services to his clients, producing a site plan for Glen Ellen (now lost), recommending books on the subject to George Merritt for his estate Lyndhurst, and meeting with Cocke to discuss planting at Belmead.<ref>Susanne Brendel-Pandich, “From Cottages to Castles: The Country House Designs of Alexander Jackson Davis,” in ''Alexander Jackson Davis, American Architect, 1803-1892'', ed. Amelia Peck (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rizzoli, 1992), 60 (book recommendations for Merritt), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/WLVSXGXF view on Zotero]; Snadon 1988, 98 (lost Glen Ellen site plan), 208-209 (visit to Belmead to discuss planting), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> Even his more modest residential floorplans sometimes indicated landscape elements such as [[Terrace/Slope|terraces]], [[walk]]s, [[drive]]s, [[shrubbery]], grass, and plants, as in the 1849 drawings for his mother Julia Jackson Davis’s Kirri Cottage [Fig. 10]. Davis’s university campus proposals reveal a consistent approach to institutional landscapes, recognizing not only the aesthetic but also the educational and practical functions of gardens, [[lawn]]s, and [[walk]]s. His 1838 plan for the University of Michigan features two square [[botanic garden]]s filled with geometric [[bed]]s arranged around oval [[fountain]]s, divided by a tree-lined [[avenue]] [Fig. 11]. His later design for the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, (1850–1858) likewise emphasizes a tree-lined [[avenue]], but asymmetrically locates both sections of the [[botanic garden]]s on the east edge of the campus. | ||

| − | [[File:1253.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 10, ]] | + | [[File:1253.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 10, Alexander Jackson Davis, Kirri Cottage for Julia Jackson Davis, 1849.]] |

Davis developed his ideas about [[picturesque]] buildings and landscapes from popular English theoretical and practical texts. His library contained works on aesthetic theories of the picturesque such as Edmund Burke’s ''A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful'' (1757), Uvedale Price’s ''Essay on the Picturesque, As Compared with the Sublime and The Beautiful'' (1794), and Richard Payne Knight’s ''An Analytical Inquiry into the Principles of Taste'' (1805), as well as treatises by [[picturesque]] landscape painters like William Gilpin (1724–1804).<ref>Snadon 1988, 566, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> Davis was also familiar with more practical books on [[landscape gardening]], especially the work of Humphry Repton and Thomas Whately, of whose 1770 ''Observations on Modern Gardening'' Davis asserted “this is ''the classic'' on modern gardening.”<ref>Typescript, Lyndhurst Archives, as cited in Brendel-Pandich 1992, 60, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/WLVSXGXF/q/brendel view on Zotero].</ref> He saw [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing]] as the latest in this illustrious series, writing in a letter to the noted artist and inventor Samuel Morse (1791–1872), “Of course your landscape gardening is going on according to Whatley, Repton, [[John Claudius Loudon|Loudon]] & [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing]], and is immediately to exhibit the most finished illustrations of Natural Beauty—the art modestly retiring within the background.”<ref>Alexander Jackson Davis, “Letter from Alexander Jackson Davis to Samuel Morse,” [https://www.loc.gov/resource/mmorse.031001/?sp=167 September 5, 1852], Samuel Finley Breese Morse papers, 1793–1944, General Correspondence and Related Documents, Bound volume— 17 April 1852–7 January 1853, Library of Congress. Cited in O’Malley 2016, 83, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/RUA439AW view on Zotero]. For a discussion of Davis collaboration with Morse, see Peter A. Watson, “Picturesque Transformations: A. J. Davis in the Hudson Valley and Beyond” (M.A., Columbia University, 2012), 139, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/C7YBAY2K view on Zotero].</ref> The works of these theorists emphasized a reciprocal aesthetic relationship between architecture and landscape that Davis echoed in the introduction to ''Rural Residences'', but sometimes overlooked in his practice.<ref>Snadon 1988, 16, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> | Davis developed his ideas about [[picturesque]] buildings and landscapes from popular English theoretical and practical texts. His library contained works on aesthetic theories of the picturesque such as Edmund Burke’s ''A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful'' (1757), Uvedale Price’s ''Essay on the Picturesque, As Compared with the Sublime and The Beautiful'' (1794), and Richard Payne Knight’s ''An Analytical Inquiry into the Principles of Taste'' (1805), as well as treatises by [[picturesque]] landscape painters like William Gilpin (1724–1804).<ref>Snadon 1988, 566, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> Davis was also familiar with more practical books on [[landscape gardening]], especially the work of Humphry Repton and Thomas Whately, of whose 1770 ''Observations on Modern Gardening'' Davis asserted “this is ''the classic'' on modern gardening.”<ref>Typescript, Lyndhurst Archives, as cited in Brendel-Pandich 1992, 60, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/WLVSXGXF/q/brendel view on Zotero].</ref> He saw [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing]] as the latest in this illustrious series, writing in a letter to the noted artist and inventor Samuel Morse (1791–1872), “Of course your landscape gardening is going on according to Whatley, Repton, [[John Claudius Loudon|Loudon]] & [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing]], and is immediately to exhibit the most finished illustrations of Natural Beauty—the art modestly retiring within the background.”<ref>Alexander Jackson Davis, “Letter from Alexander Jackson Davis to Samuel Morse,” [https://www.loc.gov/resource/mmorse.031001/?sp=167 September 5, 1852], Samuel Finley Breese Morse papers, 1793–1944, General Correspondence and Related Documents, Bound volume— 17 April 1852–7 January 1853, Library of Congress. Cited in O’Malley 2016, 83, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/RUA439AW view on Zotero]. For a discussion of Davis collaboration with Morse, see Peter A. Watson, “Picturesque Transformations: A. J. Davis in the Hudson Valley and Beyond” (M.A., Columbia University, 2012), 139, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/C7YBAY2K view on Zotero].</ref> The works of these theorists emphasized a reciprocal aesthetic relationship between architecture and landscape that Davis echoed in the introduction to ''Rural Residences'', but sometimes overlooked in his practice.<ref>Snadon 1988, 16, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8YX2TPPX view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | [[File:0425.jpg|thumb|Fig. 11, ]] | + | [[File:0425.jpg|thumb|Fig. 11, Alexander Jackson Davis, Design for University of Michigan (elevation and plan of building and grounds), c. 1838.]] |

Although Davis continued to design and redesign projects until his death in 1892, his commissions waned in the 1860s and 1870s following the American Civil War, as the Second Empire and High Victorian Gothic styles came to dominate popular taste.<ref>His most notable late commission consisted of designs drawn and built between 1853 and 1860 for a residential development in New Jersey known as Llewellyn Park. Richard Guy Wilson, “Idealism and the Origin of the First American Suburb: Llewellyn Park, New Jersey,” ''American Art Journal'' 11, no. 4 (1979): 79–90, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/LYZNEUNK view on Zotero].</ref> Through his architectural designs and site plans, Davis established a spatial and stylistic vocabulary for [[picturesque]] rural villas that adapted European historical models for American clients and landscapes. His many lithographs, sketches, and watercolors document public and private landscapes as they were conceived and constructed in the early nineteenth century. | Although Davis continued to design and redesign projects until his death in 1892, his commissions waned in the 1860s and 1870s following the American Civil War, as the Second Empire and High Victorian Gothic styles came to dominate popular taste.<ref>His most notable late commission consisted of designs drawn and built between 1853 and 1860 for a residential development in New Jersey known as Llewellyn Park. Richard Guy Wilson, “Idealism and the Origin of the First American Suburb: Llewellyn Park, New Jersey,” ''American Art Journal'' 11, no. 4 (1979): 79–90, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/LYZNEUNK view on Zotero].</ref> Through his architectural designs and site plans, Davis established a spatial and stylistic vocabulary for [[picturesque]] rural villas that adapted European historical models for American clients and landscapes. His many lithographs, sketches, and watercolors document public and private landscapes as they were conceived and constructed in the early nineteenth century. | ||

Revision as of 13:35, June 26, 2019

Alexander Jackson Davis (1803–1892) was one of the most influential American residential architects of the nineteenth century. His designs for country houses illustrated publications on landscape gardening and rural life that established an architectural vocabulary for American picturesque landscape design between 1835 and 1850. Davis’s copious drawings and watercolors provide idealized documents of mid-nineteenth-century designed landscapes as they were built and imagined.

History

Born on July 24, 1803 in New York City, Alexander Jackson Davis [Figs. 1 & 2] was raised and educated in Utica and Auburn, New York. After apprenticing with a publisher in Alexandria, Virginia between 1818 and 1823 (at the time still within the District of Columbia), Davis moved to New York City to study design at the American Academy of the Fine Arts, the New York Association of Artists, and the Antique School of the National Academy of Design.[1] During this period, Davis published a series of lithographs depicting urban landscapes as Views of the Public Buildings in the City of New-York, [Fig. 3], and provided material to early American illustrated journals like the New-York Mirror [Fig. 4]. Davis’s career as an architect began in 1829 when he entered into a partnership with the established architect Ithiel Town (1784–1844). For six years Davis collaborated with Town on civic projects and public buildings, mostly neoclassical in plan and elevation. As historian of architecture Patrick Snadon has noted, Davis studied the buildings of Benjamin Henry Latrobe during this period of his career, creating detailed drawings of the United States Capitol between 1832 and 1834 [Fig. 5].[2] Davis also worked with Town on the design of a residential villa known as Glen Ellen (1833), a building type to which Davis would devote much of his active career as an architect. In 1835, Davis parted ways with Town. By that time, Davis had already begun independently designing Hudson river estates for patrons like the banker Robert Donaldson (1834, never built).

With Donaldson’s support and encouragement, Davis began work on a book composed of architectural drawings and plans accompanied by short explanatory texts (view text). In 1837, Davis published this work, Rural Residences, Etc. Consisting of Designs, Original and Selected, for Cottages, Farm-Houses, Villas, and Village Churches: With Brief Explanations, Estimates, and a Specification of Materials, Construction, Etc., in periodical installments each containing four designs. The concept and format seem to have been modeled on the British architect and artist John Buonarotti Papworth's 1818 publication with the strikingly similar title Rural Residences, Consisting of a Series of Designs for Cottages, Decorated Cottages, Small Villas, and Other Ornamental Buildings. As in Papworth's work, the floorplans within Davis's Rural Residences do not extend to the surrounding landscape, but the perspectival drawings suggest complementary planting designs. Davis’s brief introduction emphasizes the landscape as a design factor in terms of the “connexion [of a building] with its site.”[3]

Donaldson introduced Davis to the nurseryman and landscape gardener Andrew Jackson Downing in 1838 (view text), and Davis would go on to design Downing’s own Hudson River estate Highland Park (1838–1839).[4] Between 1839 and 1850, Downing used woodcuts of designs and sketches by Davis to illustrate many of his publications, including A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (first published in 1841), The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), and The Horticulturist. The publicity generated by these works made Davis one of the most desirable architects for wealthy owners of rural estates and plantations. Donaldson was also instrumental in helping Davis obtain commissions for campus designs, including the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, writing in 1843 that “Mr Davis is the readiest & most skillful draughtsman that I know, and can furnish you with designs for Exterior Elevations or Interior Decorations—plans for Gates, Fences, & improving grounds about Buildings—in fact the danger is, when he mounts the Pegasus of Design, he may require the restraining taste of another” (view text).

In his publications and his flourishing practice throughout the 1840s, Davis developed two main types of residential structures: large, asymmetrical villas for wealthy clients characterized by two main wings in an L-shaped configuration, and smaller rectangular cottages intended for clients of more modest means.[5] Both types featured a veranda or porch wrapped around the building, which connected the house to its immediate surroundings, while his villas often incorporated “prospect towers” or “prospect rooms” that provided sweeping views of the landscape, as seen in his design for Murray Hill (view text) [Fig. 6].[6] Davis also designed many small, free-standing structures for contemplating the landscape, including tented seats [Fig. 7], and summerhouses [Fig. 8], inspired by the publications of J. C. Loudon and Batty Langley.[7] Downing’s publications further emphasized the visual relationship between Davis’s designs and the surrounding landscape, recommending paint colors that harmonized with green foliage.

In addition to his clients in the New York area, Davis found patronage among several owners of plantations in the American south. These commissions reveal how Davis, like other architects of the era, adapted the picturesque to aestheticize or obscure built landscapes of slavery.[8] With a workforce of more than 500 people, Philip St. George Cocke’s Belmead Plantation (1845–1848), near Powhatan, Virginia, was comparable in scale to large southern plantations, such as Daniel and Martha Turnbull’s Rosedown Plantation (1835–1845) in Louisiana.[9] At Belmead, Davis and Cocke modified picturesque designs for cottages and gatehouses to function as slave quarters. Architectural decorations featured heraldic depictions of cotton, tobacco, wheat, and corn that brought the landscape into the main house, but elided the bodies of the enslaved people who cultivated them.[10] Architectural historian Daniel Bluestone has shown that much of the construction labor at Belmead was carried out by enslaved people, and argued that Davis’s designs for the estate hid slavery behind a picturesque veneer connoting refinement and taste. At Loudoun Plantation near Lexington, Kentucky (1849–1852), Davis accommodated his client Francis Key Hunt’s requests to eliminate prominent windows from the northeast face of his residence, overlooking the “private yard” in which his enslaved African American servants lived and worked.[11] Whether by altering the designs of slave quarters at Belmead or the main plantation house at Loudoun, Davis used picturesque designs to indulge the ideological blindspots of these clients.

In addition to marketing himself as an architect, Davis also advertised his ability to create designs and plans for “landscape gardening” (view text). Several of Davis’s site plans for villas and universities survive. His most comprehensive residential site plan, made for Blithewood [Fig. 9], is labelled with a variety of features including a boathouse on the river, a rustic tent, a cataract, a barn, a grass field, and two springs. Davis provided a variety of landscape gardening services to his clients, producing a site plan for Glen Ellen (now lost), recommending books on the subject to George Merritt for his estate Lyndhurst, and meeting with Cocke to discuss planting at Belmead.[12] Even his more modest residential floorplans sometimes indicated landscape elements such as terraces, walks, drives, shrubbery, grass, and plants, as in the 1849 drawings for his mother Julia Jackson Davis’s Kirri Cottage [Fig. 10]. Davis’s university campus proposals reveal a consistent approach to institutional landscapes, recognizing not only the aesthetic but also the educational and practical functions of gardens, lawns, and walks. His 1838 plan for the University of Michigan features two square botanic gardens filled with geometric beds arranged around oval fountains, divided by a tree-lined avenue [Fig. 11]. His later design for the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, (1850–1858) likewise emphasizes a tree-lined avenue, but asymmetrically locates both sections of the botanic gardens on the east edge of the campus.

Davis developed his ideas about picturesque buildings and landscapes from popular English theoretical and practical texts. His library contained works on aesthetic theories of the picturesque such as Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), Uvedale Price’s Essay on the Picturesque, As Compared with the Sublime and The Beautiful (1794), and Richard Payne Knight’s An Analytical Inquiry into the Principles of Taste (1805), as well as treatises by picturesque landscape painters like William Gilpin (1724–1804).[13] Davis was also familiar with more practical books on landscape gardening, especially the work of Humphry Repton and Thomas Whately, of whose 1770 Observations on Modern Gardening Davis asserted “this is the classic on modern gardening.”[14] He saw Downing as the latest in this illustrious series, writing in a letter to the noted artist and inventor Samuel Morse (1791–1872), “Of course your landscape gardening is going on according to Whatley, Repton, Loudon & Downing, and is immediately to exhibit the most finished illustrations of Natural Beauty—the art modestly retiring within the background.”[15] The works of these theorists emphasized a reciprocal aesthetic relationship between architecture and landscape that Davis echoed in the introduction to Rural Residences, but sometimes overlooked in his practice.[16]

Although Davis continued to design and redesign projects until his death in 1892, his commissions waned in the 1860s and 1870s following the American Civil War, as the Second Empire and High Victorian Gothic styles came to dominate popular taste.[17] Through his architectural designs and site plans, Davis established a spatial and stylistic vocabulary for picturesque rural villas that adapted European historical models for American clients and landscapes. His many lithographs, sketches, and watercolors document public and private landscapes as they were conceived and constructed in the early nineteenth century.

—Alexander Brey

Texts

- [Davis, Alexander Jackson, 1837, introduction to Rural Residences (Davis 1837: n.p.)[18] Back up to History

- “RURAL DESIGNS.

- “ADVERTISEMENT.

- “THE following series of designs has been prepared in compliance with the wishes of a few gentlemen who are desirous of seeing a better taste prevail in the Rural Architecture of this country.

- “The bald and uninteresting aspect of our houses must be obvious to every traveller; and to those who are familiar with the picturesque Cottages and Villas of England, it is positively painful to witness here the wasteful and tasteless expenditure of money in building.

- “Defects are felt, however, not only in the style of the house but in the want of connexion with its site,—in the absence of appropriate offices,—well disposed trees, shrubbery, and vines,—which accessories give an inviting and habitable air to the place.

- “The Greek Temple form, perfect in itself, and well adapted as it is to public edifices, and even to town mansions, is inappropriate for country residences, and yet it is the only style ever attempted in our more costly habitations. The English collegiate style, is for many reasons to be preferred. It admits of greater variety both of plan and outline;—is susceptible of additions from time to time, while its bay windows, oriels, turrets, and chimney shafts , give pictorial effect to the elevation.

- “The principal object aimed at in these designs has been to give as much character to the exteriors as possible;—should they answer in any degree the purposes for which they were projected, the architect may submit, at a future period, designs for more expensive structures. . . .

- “VILLA IN THE ENGLISH COLLEGIATE STYLE.

- “This plan was designed for Robert Donaldson, Esq. of Blithewood, on the Hudson River, to whose taste and aid, in selecting designs, the public are mainly indebted for the present publication.

- “The design is irregular, and suited to scenery of a picturesque character, and to an eminence commanding an extensive prospect. . . . ”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, December 12, 1838, letter to arrange a first meeting with Alexander Jackson Davis (quoted in Pierson 1978: 351)[19]

- “Dear Sir—

- “I am at present busily engaged in preparing a work for the press on Landscape Gardening and Rural Residences with the view of improving if possible the taste in these matters in the United States.

- “My friend, R. Donaldson, Esq., has informed me that he has mentioned my name to you and that you were so kind as to offer to show me any work, views or plans in your possession which might be of any service to me.

- “I shall probably be in town on Saturday morning next when I shall have the pleasure of calling up on you and be glad to avail myself of your very kind offer.

- “Yours truly,

- “A. J. Downing”

- Donaldson, Robert, December 16, 1843, letter to David L. Swain (1801–1868), president of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, concerning Davis’s work on designs for the campus[20] Back up to History

- “Blithewood Decr. 16th 1843

- “Dear Sir

- “Your favor of the 28th came to hand in due time and I have since communicated with Mr Davis. He is ready to make you a visit ‘about the middle of next month,’ for which purpose, remit, if you please, a Draft for $100 in my [power] upon some New York Bank and I will forthwith give him directions to proceed. The $100 will barely pay his traveling expenses, though he is willing for that sum to go on & stay three days, during which time he will make any pencil Drawings of Buildings, gates, &c &c that you may desire. But if more elaborate working drawings & specifications are required he will charge accordingly & as you may agree on before using them. Mr Davis is the readiest & most skillful draughtsman that I know, and can furnish you with designs for Exterior Elevations or Interior Decorations—plans for Gates, Fences, & improving grounds about Buildings—in fact the danger is, when he mounts the Pegasus of Design, he may surprise the restraining taste of another.

- “There is no room for attempting Landscape Gardening, about the College Buildings. All that can be done, in my opinion, is to trim the defective limbs of trees, remove the failing trees, grade the roads & cover them (if it can be got) with gravel, remove the surface stone from the grounds & enrich them so as to get grass to grow (at least in the more open spaces). The rears of the adjoining Lots to be excluded from sight by planting a thick belt of trees along the boundary of the campus. This belt may vary in width & be composed of any trees, most likely to you—viza. Willows, Elms, Thorns, &c.

- “Buy all the stable manure which you can get & mix it in alternate layers with swamp muck or vegetable mould, of which I think there is a deposit South East of the Colleges, and this compost will answer admirably for top dressing the campus and for planting trees & shrubs.

- “Substantial walls of enclosure & handsome Gates, and good roads of approach to the Village is all that I would recommend to be attempted until you are ready to proceed with my favorite plan of a Botanic Garden &c about which I intend to write more fully.

- “Unless I am prevented by something unforeseen, I intend to visit North Carolina in March and as I shall have occasion to go into Chatham County, I may deviate from my route, so far as to go through C Hill, if you should think that I can be of any service in promoting the plans of improvement in what you are engaged.

- “Yours very truly,

- “Robert Donaldson

- “Gov. Swain

- “Chapel Hill

- “P S The Cedar tree or any evergreen will answer well for the belt of trees, but they are difficult to transplant”

- Davis, Alexander Jackson, April 17, 1844, letter to David L. Swain (1801–1868), president of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill[21]

- “. . . .The Committee adopted my plans, and seemed disposed to carry through the proposed alterations in the South Building, such as adding a Dome, and fitting up the attic: Working Drawings for the Dormitories, and also drawings for the South building I engaged to make for one hundred dollars, in addition to what I have already received for traveling expenses, on receiving instructions from you to that effect with intelligence of the work being in progress. At my leisure I intend to add a plan for your botanic garden. Have you seen, and what do you think of Dr. Dewey’s Discourse on Slavery? If you have not seen it in the papers, I will send it to you in pamphlet.

- “After leaving you, I passed a very pleasant time at the Governor’s in Raleigh, the weather being fine and admitting of some rambles with the young ladies on sketching expeditions. . . .”

- Davis, Alexander Jackson, n.d. [after 1845 when Davis designed a house for William Coventry Waddell], draft of an entry for Rural Residences or another uncompleted publication[22] Back up to HIstory

- “SUBURBAN GOTHIC VILLA

- “IT is an object of this work to exhibit at least one illustration in each of the several prominent styles of building, with hints on construction, so that proprietors (their own landscape gardeners) consulting it, may determine upon that most fitting their particular site, as well as bias of mind in association of thought, and account of accommodation. We therefore give two subjects upon suburban dwellings: the one more simple and economical than the other, but each exhibiting features characterising the pointed (gothic or picturesque) manner of building. The View and plan of Mr. Waddell’s house is sufficiently explanatory without minute description in words. It stands upon high ground south of the Croton reservoir, on the west side of the fifth avenue, between 37th and 38th streets overlooking the greater part of N.Y. island,—the view from the prospect tower being very extensive, commanding the bay, Staten Island, Long island, West Chester, and the Jersey shore. The grade of the avenue at this site being the natural surface of the ground, has enable the owner to preserve several of the ancient trees, which so much adorn it, rendering it thereby a spot unequalled in a city of so much change as N.Y. The park in which it is situated, with its carriage road, lined with stately elms and black walnuts, was formerly the residence of the late Wm. Ogden, Esq., who from his lofty seclusion, looked upon the distant city, as a place only to be reached by great exertion, and some travel, little dreaming that the city would come to him. The Vth avenue commences at the Washington parade ground and terminates at Harlem river. No avenue in the city affords finer sites for building, salubrity of air, or extensive prospect.

- “Description.

- “Construction.—The Great tower, is 10 ft in diameter, containing a spiral stair way, leading to a prospect room at the summit. The closet turret is 4ft. The S. gable presents corbelled turrets, with a finial on top. Below is a semi octagon bay window, glazed on 3 sides, with stained glass. The oval window of 2nd story, like all windows of this name, is corbelled in the under part, and it projects a semi-hexagon from the wall. An oriel window may be circular or polygonal. The projection on the left, flanked by square turrets, is part of a picture gallery. Beyond this is a green house, and gardener’s cottage. On the right is seen the verge board gable of the coach house, and beyond is part of the great distributing reservoir of the croton. The material for such a building may be brick, laid open, or hollow in the walls, and stuccoed in imitation of marble or other stone. The cornice may be of wood, painted to match. Most of the trimmings, such as battlements copings, window hoods, water table and steps, are of sand stone. The roof is covered with slate.”

- Davis, Alexander Jackson, n.d., draft text for an advertisement[23] Back up to History

- “Practical Architecture.

- “Designs and specifications, with working details for building.

- “City and Country.

- “Store fronts, Banks, ~Churches,~ Dwellings, Schools.

- “Also, Landscape gardening and furniture.

- “Alex. J. Davis., Architect, N.Y. No. 203 West 11th St.

- “From long study and extensive practice in construction and the accumulation of plans, books, models and prints, he is enabled to exhibit illustrations in varied style, and point to executed works; which may be visited by those wishing to build, comment upon and improve, for convenience, fitness and economy; see the ‘House of Mansions’ Murray Hill; E.C. Litchfield’s Prospect Park; Kent’s, Bayside; S. Wilde’s, Montclair; Geo. Merrit, Tarrytown. Terms for full professional services, five per ct. on given estimate. Without superintendence, three per cent on probable cost. Set of drawings with specifications to obtain an estimate 1 per cent.

- “Drawings when taken separately, Medium class of buildings,

- “Principal floor plan— 15.00 Section showing interior 10.00

- “Elevation principal front— 15.00 Upper story plans— 5.00

- “Basement Plan— 5.00 Specification in detail— 15.00

- “BUILDING COMMITTY [sic]”

- “Plans examined & errors exposed in writing.”

Images

Alexander Jackson Davis, “Montgomery Place,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 2, no. 4 (October 1847): pl. opp. 153.

Alexander Jackson Davis, “View in the Grounds at Blithewood,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), frontispiece.

Alexander Jackson Davis, “Bank-Side Walk,” Blithewood, 1849.

Other Resources

A Digitization of Davis’s Rural Residences

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: Alexander Jackson Davis (1803–1892)

The Cultural Landscape Foundation

Finding Aid for A. J. Davis papers at Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

Finding Aid for the Alexander Jackson Davis Papers in the New York Public Library

Finding Aid and Digitized documents from the Alexander Jackson Davis papers at the New York Historical Society

Finding Aid for Alexander Jackson Davis papers at Winterthur

Notes

- ↑ For an overview of Davis’s education, see Carrie Rebora, “Alexander Jackson Davis and the Arts of Design,” in Alexander Jackson Davis, American Architect, 1803-1892, ed. Amelia Peck (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rizzoli, 1992), 25–31, view on Zotero; John Cornelius Donoghue, “Alexander Jackson Davis, Romantic Architect, 1803-1892.” (Ph.D., New York University, 1977), 67–84, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Patrick A. Snadon, review of Review of Alexander Jackson Davis, American Architect 1803-1892, by Amelia Peck, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 52, no. 4 (1993): 495, view on Zotero. For an overview of Davis’s work on public buildings, see Francis R. Kowsky, “Simplicity and Dignity: The Public and Institutional Buildings of Alexander Jackson Davis,” in Alexander Jackson Davis, American Architect, 1803-1892, ed. Amelia Peck (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rizzoli, 1992), 41–57, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Jackson Davis, Rural Residences, Etc. Consisting of Designs, Original and Selected, for Cottages, Farm-Houses, Villas, and Village Churches: With Brief Explanations, Estimates, and a Specification of Materials, Construction, Etc. (New York, 1837), n.p., view on Zotero.

- ↑ Patrick Alexander Snadon, “A. J. Davis and the Gothic Revival Castle in America, 1832-1865” (Ph.D., Cornell University, 1988), 173, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For a discussion of the villa designs, which employed massing and decorative elements to emphasize “river-front” and “road front” facades, see Snadon 1988, 81–82, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Snadon 1988, 73 (belvederes), 75 (verandas), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Snadon 1988, 80, view on Zotero.

- ↑ See also the work of William Birch for Rosalie Stier Calvert at Riversdale, mentioned in Therese O’Malley, “‘Models in This Art’: Tracing the Brownian Landscape Tradition in America,” Garden History 44, no. Suppl. 1 (Autumn 2016): 78–79, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Daniel Bluestone, “A. J. Davis’s Belmead: Picturesque Aesthetics in the Land of Slavery,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 71, no. 2 (2012): 147, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Snadon 1988, 201, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Patrick Snadon, “Loudoun: Two New York Architects and a Gothic Revival Villa in Antebellum Kentucky,” The Kentucky Review 9, no. 3 (October 1, 1989): 68–72, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Susanne Brendel-Pandich, “From Cottages to Castles: The Country House Designs of Alexander Jackson Davis,” in Alexander Jackson Davis, American Architect, 1803-1892, ed. Amelia Peck (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rizzoli, 1992), 60 (book recommendations for Merritt), view on Zotero; Snadon 1988, 98 (lost Glen Ellen site plan), 208-209 (visit to Belmead to discuss planting), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Snadon 1988, 566, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Typescript, Lyndhurst Archives, as cited in Brendel-Pandich 1992, 60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Jackson Davis, “Letter from Alexander Jackson Davis to Samuel Morse,” September 5, 1852, Samuel Finley Breese Morse papers, 1793–1944, General Correspondence and Related Documents, Bound volume— 17 April 1852–7 January 1853, Library of Congress. Cited in O’Malley 2016, 83, view on Zotero. For a discussion of Davis collaboration with Morse, see Peter A. Watson, “Picturesque Transformations: A. J. Davis in the Hudson Valley and Beyond” (M.A., Columbia University, 2012), 139, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Snadon 1988, 16, view on Zotero.

- ↑ His most notable late commission consisted of designs drawn and built between 1853 and 1860 for a residential development in New Jersey known as Llewellyn Park. Richard Guy Wilson, “Idealism and the Origin of the First American Suburb: Llewellyn Park, New Jersey,” American Art Journal 11, no. 4 (1979): 79–90, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Davis 1837, n.p., view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pierson 1978, 351, view on Zotero

- ↑ Robert Donaldson, “Letter from Robert Donaldson to David L. Swain,” December 16, 1843, University of North Carolina Papers (#40005), University Archives, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Jackson Davis, “Letter from A. J. Davis to David L. Swain,” April 17, 1844, University of North Carolina Papers (#40005), University Archives, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Jackson Davis, “Suburban Gothic Villa” (Manuscript, n.d.), Alexander Jackson Davis collection, 1837-1888, Series 2. Notes, drafts, and drawings, New-York Historical Society, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Jackson Davis, “Draft of Advertisement for A.J. Davis’s Architecture Firm, with Notice of Sale of 6.25 Acres of Land on the S. Orange Mountain on Verso” (Manuscript, n.d.), Alexander Jackson Davis collection, 1837-1888, Series 2. Notes, drafts, and drawings, New-York Historical Society, view on Zotero.