Difference between revisions of "Montgomery Place"

(→Overview: fixed en-dashes in date ranges) |

(→History: trying to figure out what to do with "Back Up to History" for second link to Smith citation) |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

<span id="DowningEditorial_cite"><span>The longest description of Montgomery Place was published in 1847, when Downing devoted an entire editorial to it in the ''Horticulturist'' ([[#DowningEditorial|view text]]), illustrated with prints based on sketches by Davis [Fig. 5]. In Downing’s description, the estate exemplifies the rugged and romantic natural beauty of the Hudson River Valley tempered with elements of a modern garden in the [[picturesque]] style. The most notable features included a path along the shore of the Hudson, a trail at the wilderness and lake along the Sawkill creek, a conservatory and flower garden near the main house, and a scenic drive suitable for “exercise in the carriage, or on horseback” that wound through the property. Small [[bridge]]s, a “[[pavilion]],” and an octagonal “rustic [[temple]],” emphasized the scale of the forty-foot waterfalls of the Sawkill, the lake, the woods, and the silhouettes of the Catskills hovering on the horizon across the river [Fig. 6]. The conservatory and arboretum provided not only “scenic effect,” but also controlled environments in which the owners and visitors could systematically analyze and compare individual species. Flower gardens nearby, laid out in a [[parterre]] described as a “rich oriental pattern of carpet or embroidery,” and a carriage drive through the wooded area in the southern part of the property offered yet other ways to experience the property. | <span id="DowningEditorial_cite"><span>The longest description of Montgomery Place was published in 1847, when Downing devoted an entire editorial to it in the ''Horticulturist'' ([[#DowningEditorial|view text]]), illustrated with prints based on sketches by Davis [Fig. 5]. In Downing’s description, the estate exemplifies the rugged and romantic natural beauty of the Hudson River Valley tempered with elements of a modern garden in the [[picturesque]] style. The most notable features included a path along the shore of the Hudson, a trail at the wilderness and lake along the Sawkill creek, a conservatory and flower garden near the main house, and a scenic drive suitable for “exercise in the carriage, or on horseback” that wound through the property. Small [[bridge]]s, a “[[pavilion]],” and an octagonal “rustic [[temple]],” emphasized the scale of the forty-foot waterfalls of the Sawkill, the lake, the woods, and the silhouettes of the Catskills hovering on the horizon across the river [Fig. 6]. The conservatory and arboretum provided not only “scenic effect,” but also controlled environments in which the owners and visitors could systematically analyze and compare individual species. Flower gardens nearby, laid out in a [[parterre]] described as a “rich oriental pattern of carpet or embroidery,” and a carriage drive through the wooded area in the southern part of the property offered yet other ways to experience the property. | ||

| − | With the exception of the main house, the architectural elements described by Downing no longer survive. Watercolor sketches and architectural drawings by Davis, however, give a sense of their varied styles and plans. Close to the house, neo-classical elements prevailed [Fig. 7], while rustic and neo-gothic structures dotted the periphery of the estate [Fig. 8-9]. The “temple” and other buildings were characterized by triangular, square, or octagonal plans, and situated with [[view]]s of the river, the waterfalls, and the lake. Another architectural rendering by the Philadelphia furniture-maker and architect John Hare Otton depicts a fantastical, four-tiered garden pagoda [Fig. 10], which he designed for the estate c. 1839–1847. | + | With the exception of the main house, the architectural elements described by Downing no longer survive. Watercolor sketches and architectural drawings by Davis, however, give a sense of their varied styles and plans. Close to the house, neo-classical elements prevailed [Fig. 7], while rustic and neo-gothic structures dotted the periphery of the estate [Fig. 8-9]. The “temple” and other buildings were characterized by triangular, square, or octagonal plans, and situated with [[view]]s of the river, the waterfalls, and the lake. Another architectural rendering by the Philadelphia furniture-maker and architect John Hare Otton depicts a fantastical, four-tiered garden pagoda [Fig. 10], which he designed for the estate c. 1839–1847. Visitors especially remarked on the exceptional beauty of Otton’s [[arbor]]s, although no drawings of them survive ([[#Smith|view text]]). Robert Toole has connected these little buildings to French developments in the use of built landmarks known as ''fabrique'', which the Livingstons may have experienced firsthand during their travels in France. |

Well into the 1860s, Montgomery Place continued to occupy a prominent place in the pantheon of American landscape design. <span id="Lossing_cite"></span>Descriptions and depictions of the estate circulated both within America, and internationally in publications like London’s Art-Journal in 1860 [Fig. 11] ([[#Lossing|view text]]). Following the death of Cora Barton in 1873, the estate passed to sister and brother Louise Livingston Hunt (1873–1914) and Carleton Hunt (1873–1921), who decided to scale back the cost and effort necessary for the maintenance of the estate. They demolished the grand conservatory and elaborate flower beds that formed the centerpiece of Louise and Cora’s garden, replacing them with “a simple but well-framed [[lawn]]” in the decades following the Civil War. The current condition of the gardens, lawns, and greenhouse primarily reflect the additions and renovations of Violetta Delafield (1875–1949), who transformed the landscape of the estate c. 1920–1940 based on her preferences for the smaller garden rooms characteristic of the Arts and Crafts style. The Sleepy Hollow Restorations preservation society, known today as Historic Hudson Valley, acquired the estate from the Delafield family in 1986. In 2016 they sold it to Bard College, located on the neighboring Blithewood property. | Well into the 1860s, Montgomery Place continued to occupy a prominent place in the pantheon of American landscape design. <span id="Lossing_cite"></span>Descriptions and depictions of the estate circulated both within America, and internationally in publications like London’s Art-Journal in 1860 [Fig. 11] ([[#Lossing|view text]]). Following the death of Cora Barton in 1873, the estate passed to sister and brother Louise Livingston Hunt (1873–1914) and Carleton Hunt (1873–1921), who decided to scale back the cost and effort necessary for the maintenance of the estate. They demolished the grand conservatory and elaborate flower beds that formed the centerpiece of Louise and Cora’s garden, replacing them with “a simple but well-framed [[lawn]]” in the decades following the Civil War. The current condition of the gardens, lawns, and greenhouse primarily reflect the additions and renovations of Violetta Delafield (1875–1949), who transformed the landscape of the estate c. 1920–1940 based on her preferences for the smaller garden rooms characteristic of the Arts and Crafts style. The Sleepy Hollow Restorations preservation society, known today as Historic Hudson Valley, acquired the estate from the Delafield family in 1986. In 2016 they sold it to Bard College, located on the neighboring Blithewood property. | ||

Revision as of 21:18, November 5, 2018

Established as a nursery and farm following the American Revolution, Montgomery Place was transformed into a pleasure garden between 1828 and 1840, tracking the emergence of a new aesthetic understanding of the American landscape. The estate served as an exemplar for theorists and landscape architects, who cited Montgomery Place in their works to illustrate key terms and design principles, and praised its successful adaptation of European picturesque design principles for American landscapes.

Overview

Alternate Names: Chateau de Montgomery

Site Dates: 1802–present

Site Owner(s): Janet Livingston Montgomery (1802–1828), Edward Livingston (1828–1836), Louise Davezac Livingston (1836–1860), Cora Livingston Barton (1860–1873), Louise Livingston Hunt (1873–1914) and her brother Carleton Hunt (1873–1921), John Ross Delafield (1921–1964), John White Delafield (1964–1985), J. Dennis Delafield (1985–1986), Sleepy Hollow Restorations/Historic Hudson Valley (1986–2016), Bard College (2016–present)

Associated People: Frederick Catherwood (architect), Andrew Jackson Downing, Alexander Jackson Davis (architect), Philip Dederick (farmer), Hans Jacob Ehlers, John George (gardener), Alexander Gilson (gardener), James McWilliams (nurseryman), Jacques-Gérard Milbert, John Hare Otton (architect)

Location: Dutchess County, NY

Condition: altered

View on Google maps

History

In 1802, Janet Livingston Montgomery (1743–1828) purchased a 242-acre farm on the bank of the Hudson River from John Van Benthuysen [Fig. 1]. Janet, the widow of General Richard Montgomery (1738–1775) who died in the American Revolutionary War, constructed a federal-style house on the property with the assistance of her nephew, William Jones (unknown–1822), which she named “Chateau de Montgomery.” Janet partnered with James McWilliams to establish a commercial nursery on her property in 1804 (view text), on which they planted 50 varieties of apple trees that her brother Robert shipped from France in 1805. Although the management of this nursery would change hands, first in 1815, to a gardener and nurseryman named John George hired by Janet as an employee rather than a business partner (view text), it remained in operation until sometime before her death in 1828. Janet and her partners planned to sell seeds to nurseries in New York, as well as to the nursery of Gordon, Dermer, & Co. in London, where American varieties were considered desirable curiosities. In addition to revenue from the nursery, Janet also made money by renting out her farmland to tenants, some of whom were responsible for managing her own livestock. According to one contract, she paid Philip Dederick one hundred and fifty dollars, along with housing, firewood, and the right to keep some farm animals in exchange for his labor managing her farmland and livestock. The 1820 census also documents twelve slaves who worked in Janet’s house and estate, whom she was eventually forced to free in 1827 when New York State abolished slavery.

Although Janet planned to leave her estate to her nephew William, his early death in 1822 preceded her own, and she willed the property to her youngest brother Edward Livingston (1764–1836) and his wife Louise d’Avezac Livingston (1781–1860). It was they who renamed it Montgomery Place. Edward and Louise occupied the estate seasonally, but they continued to rely on the kitchen garden and orchards, planting apricot, nectarine, cherry, peach, and pear trees. Drawing on their experiences in Europe, where Edward had served as United States Minister to France from 1833 to 1835, they brought a new approach to the design of the estate that emphasized visual beauty over agriculture and commerce. The new attitudes towards the landscape that emerged at estates like Hyde Park and Montgomery Place as they shed many of their earlier economic functions would spread along the Hudson River, which took on new importance as a shipping and transportation route following the completion of the Erie Canal in 1835. In 1829, Edward and Louise began laying out and building what would eventually grow to five miles of walking paths throughout the estate. His unexpected death in 1836 brought a temporary halt to these projects, and left the estate in the hands of Louise and their only child, Coralie “Cora” Livingston Barton (1806–1873), wife of Thomas Pennant Barton (1803–1869).

Louise and Cora continued to develop their property with additions and renovations. In 1839, Louise commissioned Frederick Catherwood to design a large private conservatory for the property, in which she could grow exotic plants [Fig. 2]. When John C. Cruger, who owned part of the Sawkill ravine that formed the northern border of the estate, attempted to sell it to industrial developers, Louise and her neighbor Robert Donaldson, owner of the adjacent Blithewood estate, joined together to purchase the land in 1841. Historians Johnson and Vetare have suggested that the legal agreement between them could be considered among the first scenic preservation covenants in the United States. Louise would continue to assert her control over the property and its viewshed in the coming years. She had warning signs printed and posted in 1845 to curtail recreational shooting on the land, and petitioned New York State for control of a rock in the Hudson River off the shore of her property, which, to her annoyance and moral consternation, was a popular swimming spot.

Archival documents preserve the names of a number of gardeners who worked on the estate, of whom the most significant was Alexander Gilson (1823–1889). From around 1840 to 1860, Louise and Cora employed Gilson as the head gardener of the estate. He was the child of Janet Montgomery’s African American housekeeper Sarah (Sally) and butler John, both of whom may have started working for the Livingston family as slaves. In the 1860s, Gilson cultivated a new variety of Achyranthes that was named in his honor, made known to the larger horticultural community by a notice published in the American Horticultural Annual of 1869 (view text).

Cora and Thomas Barton became friends with the noted landscape gardener and theorist Andrew Jackson Downing, who visited the estate periodically, commented on their plans for additions and renovations, and sold them plants (view text). Cora commissioned Alexander Jackson Davis to design a series of structures for the grounds, and designed her own garden furnishings. Thomas began work on an arboretum in 1846, eventually hiring Hans Jacob Ehlers, a German landscape architect, to design the grounds after an unknown designer recommended by Downing had failed to complete the project (view text) [Fig. 3]. A dispute between Thomas and Ehlers gives some idea of the expense involved in the project, for which the designer asked one hundred dollars (view text). In 1857, John Jay Smith praised the arboretum for its breadth and pioneering approach, but criticized the crowded planting of the different specimens, “which, in progress of time, must be seriously injured by their too close proximity” (view text).

A number of published images and descriptions established the natural beauty of Montgomery Place within the broader public imagination. A print of the lower falls of the Sawkill [Fig. 4] appeared in an 1828 travelogue by Jacques-Gérard Milbert, who traveled the United States collecting specimens for the Museum of Natural History in Paris. His publication offered European readers a glimpse of the property. A vivid narrative of an autumnal visit to the estate published in an 1840 issue of the New-York Mirror helped establish its reputation closer to home (view text). Downing’s Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, first published in 1841, included a short description of Montgomery Place. Holding up many of its individual feature as exemplars for imitation or inspiration, this text, more than any other, shaped the reception of the estate.

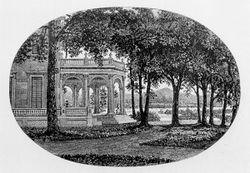

The longest description of Montgomery Place was published in 1847, when Downing devoted an entire editorial to it in the Horticulturist (view text), illustrated with prints based on sketches by Davis [Fig. 5]. In Downing’s description, the estate exemplifies the rugged and romantic natural beauty of the Hudson River Valley tempered with elements of a modern garden in the picturesque style. The most notable features included a path along the shore of the Hudson, a trail at the wilderness and lake along the Sawkill creek, a conservatory and flower garden near the main house, and a scenic drive suitable for “exercise in the carriage, or on horseback” that wound through the property. Small bridges, a “pavilion,” and an octagonal “rustic temple,” emphasized the scale of the forty-foot waterfalls of the Sawkill, the lake, the woods, and the silhouettes of the Catskills hovering on the horizon across the river [Fig. 6]. The conservatory and arboretum provided not only “scenic effect,” but also controlled environments in which the owners and visitors could systematically analyze and compare individual species. Flower gardens nearby, laid out in a parterre described as a “rich oriental pattern of carpet or embroidery,” and a carriage drive through the wooded area in the southern part of the property offered yet other ways to experience the property.

With the exception of the main house, the architectural elements described by Downing no longer survive. Watercolor sketches and architectural drawings by Davis, however, give a sense of their varied styles and plans. Close to the house, neo-classical elements prevailed [Fig. 7], while rustic and neo-gothic structures dotted the periphery of the estate [Fig. 8-9]. The “temple” and other buildings were characterized by triangular, square, or octagonal plans, and situated with views of the river, the waterfalls, and the lake. Another architectural rendering by the Philadelphia furniture-maker and architect John Hare Otton depicts a fantastical, four-tiered garden pagoda [Fig. 10], which he designed for the estate c. 1839–1847. Visitors especially remarked on the exceptional beauty of Otton’s arbors, although no drawings of them survive (view text). Robert Toole has connected these little buildings to French developments in the use of built landmarks known as fabrique, which the Livingstons may have experienced firsthand during their travels in France.

Well into the 1860s, Montgomery Place continued to occupy a prominent place in the pantheon of American landscape design. Descriptions and depictions of the estate circulated both within America, and internationally in publications like London’s Art-Journal in 1860 [Fig. 11] (view text). Following the death of Cora Barton in 1873, the estate passed to sister and brother Louise Livingston Hunt (1873–1914) and Carleton Hunt (1873–1921), who decided to scale back the cost and effort necessary for the maintenance of the estate. They demolished the grand conservatory and elaborate flower beds that formed the centerpiece of Louise and Cora’s garden, replacing them with “a simple but well-framed lawn” in the decades following the Civil War. The current condition of the gardens, lawns, and greenhouse primarily reflect the additions and renovations of Violetta Delafield (1875–1949), who transformed the landscape of the estate c. 1920–1940 based on her preferences for the smaller garden rooms characteristic of the Arts and Crafts style. The Sleepy Hollow Restorations preservation society, known today as Historic Hudson Valley, acquired the estate from the Delafield family in 1986. In 2016 they sold it to Bard College, located on the neighboring Blithewood property.

—Alexander Brey

Texts

- Contract between Janet Montgomery and James McWilliam, c. 1804 (quoted in Johnson and Vetare) Back up to History

- “Proposals

- “To take from four to ten acres of ground which shall be fenced and be Dunged every year as much as you shall require to give you your board and forty pounds a year – for the space of Seven years for taking the Charge of the Garden & Nursery. – the Profits of the last to be divided – as well as the losses and labour. If However the profits for the three first years – shall not exceed your present wagers [sic] that is to say seventy two pounds then I agree to make up that sum up to you including the forty pounds first proposed – All the present stock to be thrown in to the General stock gratis but if at any time you should wish to leave me the same numbers of stock to be left me with out Charge – If you wish to quit ere the seven years are expired, you will have a right to one third of the Nursery to dispose of as you please.

- “If you remain the seven years you will have a right to one half of the Nursery – and to dispose of as you please With respect to purchasing the whole I would agree to lump[?] the purchase and give a fare [sic] bid – but to say I will purchase each shrub and tree as they are singly sold, I cannot agree to this and therefore you shall only give me the preference to purchase & if I do not agree you shall sell to any one you please to take from the Nursery what shrubs, flowers & trees I may want for my farm excepting the Apple trees which if I should want I will agree to pay for - ”

- Janet Montgomery's account book, January 10, 1815, (quoted in Johnson and Vetare) Back up to History

- “Memorandum of an agreement Between Honnis George and Mrs. Janet Montgomery made the 10th day of January 1815 as follows Viz.t

- “1. The said George is to serve the said Mrs. Montgomery for one year to commence on the first day of March next as Gardener and Nurseryman and to attend to the collection and putting and putting up the seeds properly up for Sales.

- “2. The said J. Montgomery agrees to pay the said George for his said years services two hundred Dollars and to find him assistance when the same may be necessary. She is also to find him the Garden house to live in. Also sufficient fire wood, the privilege of keeping two pigs. She is also to keep a cow for him winter and summer.

- “3. The said George is to find himself in provision except vegetables which he has the right to take out of the Garden.

- “Witness our hands the day and year first before written.

- “Witness present

- “John Cox Jr. John George

- “Janet Montgomery”

- J. D. S., February 8, 1840, “A Visit to Montgomery-Place” (New-York Mirror 17, no. 33: 260-61) Back up to History

- “The approach to the mansion of Mrs. L. is by a road, studded on either side with a row of forest-trees standing in sentinel array, as a guard of honour come out to welcome the expected guest. This avenue opens by a wicker-gate to a broad area of mingled forest, garden, and sunny park: the view expanding and widening, until it is crowned and lost in the far-off glories of the river, the champaign country beyond, and the noble Cattskills, springing away and burying their heads in the clouds. Numberless bridle-paths run off from the carriage road; serpentining in mazy pleasure—now approaching, now receding, until, diving down some little ravines, they disappeared from the sight. The garden, which salutes you as you emerge from the deep shade of the grove, was now mourning the loss of its summer, holiday garb and showed only here and there a lingering flower, the lone companions of a bright and laughing company. The purpling fruits of summer had been gathered; autumn had touched the parterre, and shaken its rich and variegated honours to the ground; and even the sculptured gardener seemed to hang his head in sorrow, and mutter between his marble lips, “Othello's occupation's gone.” To be sure, we could commission the imagination to perform the office of nature. We could bid her summon back from their decay the flowers, tint them with the never. Ending hues of summer, hang them in ripe and nodding beauty along the winding walk, and relieve the flush and circling richness of the expanded flower, with the folded or half-opened bud. Yet this is but a tantalizing occupation. The magic pleasure, the exquisite and liquid delight which thrills us when nature herself bids the desolate stalk to bloom, adorns the naked stem with green leaves, and fills the flowering cup with the breath of perfume—these imagination cannot supply. Yet why deplore their loss the same autumnal spirit which spreads a pall over the glad beauty of the garden, covers with richest mantle the forest. The leaves of the oak and maple had been touched with the frosty influence, and were here and there borne from their withered stems and whirled upon the ground, and as we sauntered along the winding path, rustled to our tread with that gentle, melancholy stir which subdues, not saddens the mind, and fits it for a serene communion with the sobered grandeur of the season.

- “My companion was one of the few who possess that instinctive delicacy which shrinks from forcing an unseasonable gaiety upon those who, like myself, feel the influence of the dying year. Woman best knows to adapt herself to the varying mood of man, and interprets more readily than our sex the changing language of the seasons. In summer we love to see the light, graceful form of the girl, floating in a playful motion among flowers and green things; now stopping to pluck a breathing gem, and now, while you are admiring her heightened glow and beauty, breaking away and sending upon the scented breeze her innocent, free-hearted laugh. But in autumn the vivacity and glee which charmed us erewhile, seems almost to reproach us, and comes like the dying tone of a harp string snapped by too rude a hand. It may be an unmanly sensibility, but I cannot endure to hear in the woods of autumn the loud voice, awakened by hilarity, or sent out to find an echo in the answering hills and trees. When green foliage clothes the boughs, and the voices of birds are merry among the tops of the trees, then send abroad the many-tones dong and peal. But when the stir of the wind is like a complaining melody among the stricken leaves, let the hushed tone make no discord upon the great forest-harp of nature.

- “So thought my cicerone as she moved along, pointing out to my notice, in a low, subdued voice, the impressive beauties which met us. The grounds, which retreat to the north, are irregular, and endlessly varied. Sometimes they slope off by a regular descent, and again drop suddenly down; forming a dell in which, one might easily imagine, the winds strewed their couches at night, and soothed themselves to rest with the musical murmur of a little stream, which led its silver thread at the bottom. Descending farther along the edge of this ravine, we crossed a rustic bridge thrown over the brook, which here escaping from its narrow channel, defied the nimble foot of the pedestrian to leap it. A lengthening vista, formed by the branches of the linden, intertwining and bending over your head an arch, the thousand hues of their taper leaves peeping out from between the lattices, tempted you away from the water, eddying and sporting among the rocks of its bed. Mounting aby narrow path, by dint of climbing and catching to the under. Brush which lined its sides, we were warned of our close vicinity to a water fall, which a few steps forward revealed to us, dashing down a perpendicular edge, and hurrying away its chafed and foaming water to an expanded bay, into whose unruffled bosom it soon buried itself and was soothed to quiet. I have sometimes thought that to cascades nature has given a greater and more unending variety than to any other feature of her creation. Everything else has its cognate, its counterpart. Every landscape has in it something, which looks familiar and common, if not absolutely vulgar. But in the dash of water as it tumbles down and finds an echo on either shore, there is a freshness which is ever renovating, and which breaks upon you with an inspiration that verges upon ecstasy. I have seen many a waterfall, from the “cataract of Niagara” to the humble rapid; but I have never found one to which I was indifferent, which possessed the same charm, or stirred within me kindred emotions.

- “That over which we were now hanging had its own features, its guardian divinity to preside over its influences. Shall I describe it! I could only sketch a few obvious traits; who will attempt to paint the emotions which are evoked, the thousand undefined thoughts which spring and live in its roar, but flee forever as we depart 1 I could speak of the stream, plunging like a bison over a precipice, recovering from its leap, and shaking the rocks as it bounded away; of the evergreens, which seemed to love their dangerous eminence, advancing to the very brink of the shelf, and contrasting their bright hues with the milky foam into which the dusky-coloured water had been fretted; of the creeping plants, which hung their festoons over the face of the jagged rock, and fringed with living green the otherwise naked bank; -but who shall delineate the rush of memory from its secret, viewless depths, the tide of retrospection, the gush of feeling,

- ‘When thoughts on thoughts, a countless throng, Came chasing countless thoughts along?’

- “when the fountains of the mind are broken up, and its waters mingle and blend in richest confusion? Words are sometimes impotent; never more so than when employed to give an idea of reverie. After lingering sometime in silent admiration and thought, we bent our way backward along the shore of the river; delaying a little to hear the dash of the wave upon the rocks, and anon stopping upon some gentle ascent to mark the hectic beauty of the leaves, brightening under the hand of decay.”

- Downing, A. J., December 31, 1846, letter to Thomas Barton (quoted in Haley 1988: 33) Back up to History

- “Highland Gardens

- “Newburgh Dec 31: 1846

- “Dear Sir

- “You will observe that I have taken the “days of grace” which in your letter you kindly allowed me for a reply. In truth I have had so many matters of business forced upon me lately that I have had less leisure for my correspondence than usual.

- “I enclose the list with the height and prices of all that we can furnish good specimens of in the spring. If you are ready to plant more I would advise you at some time during the winter to look through the nurseries of Landreth & Fulton below Philadelphia. I understand they have some fine and rare ornamental trees.

- “I beg you to present my kind regards to Mrs. Barton & say that I not only sent Major Davezac two large plants of the Night-smelling jasmine but also two plants of the “Torreya taxifolia” a new & beautiful evergreen tree –in habit between our Hemlock & the Yew – which has been discovered in Florida where it grows 50 ft. high. I believe there have been no specimens before these sent to the Continent of Europe. I also forwarded through my London publishers a copy of the Horticulturist up to this month – all of which I trust will reach Major Davezac safely.

- “I am delighted to learn that you are about to add to the great charms of Montgomery Place by the formation of an arboretum. How few persons there are yet in this country who know anything of the individual beauty of even our own forest trees! I wish you success in so laudable an undertaking.

- “Mrs. Downing desires to join me in remembrances to Mrs. Barton & yourself & I remain

- “Dear Sir your most obt Servant

- “A.J. Downing”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, October 1847, describing Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (1847: 154–160)[1] Back up to History

- “About four hundred acres comprise the estate called Montgomery Place, a very large part of which is devoted to pleasure grounds and ornamental purposes. The every varied surface affords the finest scope for the numerous roads, drives and walks, with which it abounds. Even its natural boundaries are admirable. On the west is the Hudson, broken by islands into an outline unusually varied and picturesque. On the north, it is separated from Blithewood, the adjoining seat, by a wooded valley, in the depths of which runs a broad stream, rich in waterfalls. On the south is a rich oak wood, in the centre of which is a private drive. On the east it touches the post road. Here is the entrance gate, and from it leads a long and stately avenue of trees, like the approach to an old French chateau. Halfway up its length, the lines of planted trees give place to a tall wood, and this again is succeeded by the lawn, which opens in all its stately dignity, with increased effect, after the deeper shadows of this vestibule-like wood. . . .

- "Without going into any details of the interior, we may call attention to the unique effect of the pavilion, thirty feet wide, which forms the north wing of this house. It opens from the library and drawing-room by low windows. Its ribbed roof is supported by a tasteful series of columns and arches, in the style of an Italian arcade. As it is on the north side of the dwelling, its position is always cool in summer; and this coolness is still farther increased by the abundant shade of tall old trees, whose heads cast a pleasant gloom, while their tall trunks allow the eye to feast on the rich landscape spread around it. . . . [Fig. 1]

- “THE MORNING WALK.

- “Leaving the terrace on the western front, the steps of the visitor, exploring Montgomery Place, are naturally directed towards the river bank. A path on the left of the broad lawn leads one to the fanciful rustic-gabled seat, among a growth of locusts at the bottom of the slope. Here commences a long walk, which is the favorite morning ramble of guests. . . . Half-way along this morning ramble, a rustic seat, placed on a bold little plateau, at the base of a large tree, eighty feet above the water and fenced with a rustic barrier, invites you to linger and gaze at the fascinating river landscape here presented. . . .

- “A little farther on, we reach a flight of rocky steps, leading up to the border of the lawn. At the top of these is a rustic seat with a thatched canopy, curiously built round the trunk of an aged pine. . . . [Fig. 2]

- “THE WILDERNESS.

- “Leaving the morning walk, we enter at once into 'The Wilderness.' This is a large and long wooded valley. . . . It is covered with the native growth of trees, thick, dark, and shadowy, so that once plunged in its recesses, you can easily imagine yourself in the depths of an old forest, far away from the haunts of civilization. . . .

- “But the Wilderness is by no means savage in the aspect of its beauty; on the contrary, here as elsewhere in this demesne, are evidences, in every improvement, of a fine appreciation of the natural charms of the locality. The whole of this richly wooded valley is threaded with walks, ingeniously and naturally conducted so as to penetrate to all the most interesting points; while a great variety of rustic seats, formed beneath the threes, in deep secluded thickets , by the side of the swift rushing stream, or on some inviting eminence, enables one fully to enjoy them. . . .

- “THE CATARACT.

- “But the stranger who enters the depths of this dusky wood by this route, is not long inclined to remain here. His imagination is excited by the not very distant sound of waterfalls.

- 'Above, below, aerial murmurs swell,

- From hanging wood, brown heath and bushy dell;

- A thousand gushing rells that shun the light,

- Stealing like music on the ear of night.'

- “He takes another path, passes by an airy looking rustic bridge, and plunging for a moment into the thicket, emerges again in full view of the first cataract. Coming from the solemn depths of the woods, he is astonished at the noise and volume of the stream, which here rushes in wild foam and confusion over the rocky fall, forty feet in depth. Ascending a flight of steps made in the precipitous banks of the stream, we have another view, which is scarcely less spirited and picturesque.

- "This waterfall, beautiful at all seasons, would alone be considered a sufficient attraction to give notoriety to a rural locality in most country neighborhoods. But as if nature had intended to lavish her gifts here, she has, in the course of this valley, given two other cataracts. These are all striking enough to be worthy of the pencil of the artist, and they make this valley a feast of wonders to the lovers of the picturesque. . . .

- “THE LAKE

- “. . . . The peninsula, on the north of the lake, is carpeted with the dry leaves of the thick cedars that cover it, and form so umbragous a resting place that the sky over it seems absolutely dusky at noon day. On its northern bank is a rude sofa, formed entirely of stone. Here you linger again, to wonder afresh at the novelty and beauty of the second cascade. The stream here emerges from a dark thicket, falls about twenty feet, and then rushes away on the side of the peninsula opposite the lake. . . . [Fig. 3]

- “Winding along the sides of the valley, and stretching for a good distance across its broadest part, all the while so deeply immersed however, in its umbrageous shelter, as scarcely to see the sun, or indeed to feel very certain of our whereabouts, we emerge in the neighborhood of the CONSERVATORY.

- “This a large, isolated, glazed structure, designed by MR. CATHERWOOD, to add to the scenic effect of the pleasure grounds. On its northern side are, in summer, arranged the more delicate green-house plants; and in front are groups of large Oranges, Lemons, Citrons, Cape Jasmines, Eugenias, etc., in tubs—plants remarkable for their size and beauty. Passing under neat and tasteful archways of wirework, covered with rare climbers, we enter what is properly [Fig. 4]

- “THE FLOWER GARDEN.

- “How different a scene from the deep sequestered shadows of the Wilderness! Here all is gay and smiling. Bright parterres of brilliant flowers bask in the full daylight, and rich masses of colour seem to revel in the sunshine. The walks are fancifully laid out, so as to form a tasteful whole; the beds are surrounded by low edgings of turf or box, and the whole looks like some rich oriental pattern of carpet or embroidery. In the centre of the garden stands a large vase of the Warwick pattern; others occupy the centres of parterres in the midst of its two main divisions, and at either end is a fanciful light summer-house, or pavilion, of Moresque character. The whole garden is surrounded and shut out from the lawn, by a belt of shrubbery, and above and behind this, rises, like a noble framework, the background of trees of the lawn and the Wilderness. If there is any prettier flower garden scene than this ensemble in the country, we have not yet had the good fortune to behold it. . . .

- “THE DRIVE

- “On the southern boundary is an oak wood of about fifty acres. It is totally different in character from the Wilderness on the north, and is a nearly level or slightly undulating surface, well covered with fine Oak, Chestnut, and other timber trees. Though it is laid out the DRIVE; a sylvan route as agreeable for exercise in the carriage, or on horseback, as the 'Wilderness,' or the 'Morning Walk,' is for a ramble on foot. . . .

- “Though Montgomery Place itself is old, yet a spirit ever new directs the improvements carried on within it. Among those more worthy of note, we gladly mention an arboretum, just commenced on a fine site in the pleasure grounds, set apart and thoroughly prepared for the purpose. Here a scientific arrangement of all the most beautiful hardy trees and shrubs, will interest the student, who looks upon the vegetable kingdom with a more curious eye than the ordinary observer."

- Downing, A. J. describes someone who is almost certainly Cora Barton, 1849, “On Feminine Taste in Rural Affairs,” (Horticulturist 3, no 10: 454)

- “Almost all the really enthusiastic and energetic lady gardeners that we have the pleasure of knowing, belong to the wealthiest class in this country. We have a neighbor on the Hudson, for instance, whose pleasure-grounds cover many acres, whose flower garden is a miracle of beauty, and who keeps six gardeners at work all the season. But there is never a tree transplanted that she does not see that its roots are carefully handled; not a walk laid out that she does not mark its curves; not a parterre arranged that she does not direct its colors and groupings, and even assist in planting it. No matter what guests enjoy her hospitality, several hours every day are thus spent in out-of-door employment and from the zeal and enthusiasm with which she always talks of every thing relating to her country life, we do not doubt that she is far more rationally happy now, than when she received the homage of a circle of admirers at one of the most brilliant of foreign courts.”

- 1848 letter about the propagating pit?

- Ehlers, Hans J., 1852, Defence Against Abuse and Slander with Some Strictures on Mr. Downing’s Book on Landscape Gardening (quoted in Haley 1988: 23) Back up to History

- “In the spring of 1849, he [H. J. Ehlers] was engaged by Mr. T. Barton, of Montgomery Place, Dutchess County, to design and superintend the laying out of the grounds belonging to his country sear. An attempt had been made to do this by a person who had been recommended to Mr. Barton by Mr. Downing. The attempt had proved a complete failure. The work of two years had to be undone and begun anew. After the work was completed; Mr. Barton expressed himself satisfied with it. But although I charged him less than I considered my services worth, he has refused and still continues to refuse to pay more than about one half of my charge [about $100].”

- Smith, John Jay, 1857, “Visits to Country Places. —No. 6. Around New York” (Horticulturist 7: 22) Back up to History

- “Montgomery Place, the seat of Mrs. Edward Livingston, and occupied by herself and her children, Mr. and Mrs. T. P. Barton, was originally the residence of General Montgomery. It therefore has age and trees consequently of more antiquity than are usually seen. Its specialty now is the Arboretum, the most successful effort yet made among us, and though it has been executed at considerable cost of time, labor, and money, yet we cannot but regret that Mr. Barton has not allowed himself greater space for the future development of his various specimens, which, in process of time, must be seriously injured by their too close proximity. Nevertheless, great credit is due for this first effort.

- “In the other planting, the trees have become old stagers, and much that has been done by man represents the plantations of nature, and very beautiful and valuable they are. Combined with these, amid avenues, and shady walks, and a drive of many miles on the property, is an extensive flower-garden, the especial pet of Mrs. Barton, who has here shown effects which have not before been exhibited in this country. Her masses of roses and other flowers are particularly attractive. The arbors, overgrown with Aristolochia sipho, the Dutchman’s pipe, exceed anything of the kind we have ever seen. These were designed by Mr. Otton, a wood carver and architectural decorator, of Philadelphia, whose merits are not sufficiently known.

- “The noble stream and cascades dividing Annandale and Montgomery Place, have already been described as well as words can depict what is indescribable. In short, Montgomery Place is all that a country-seat need, and, in our climate, can be.”

- Mead, Peter B., 1861, “A Day’s Ride” (Horticulturist 16: 416)

- “Then we came to a pretty waterfall and a little lake of irregular outline, surrounded chiefly with evergreens, the deciduous trees having been mostly cut out. Passing down a narrow, well-wooded foot path, with occasional glimpses of water, we at last reached the foot of the dell, and came in full sight of the cascades, the water leaping joyously over and around the rocks, all foaming with gladness, and each drop seeming a little elfin sprite. If not grand, the scene was very beautiful. The little river is here crossed by a pretty rustic bridge, with a pavilion in the middle, commanding a fine view of the cascades and a reach of the Hudson in the opposite direction. The place was cool and refreshing; tired and sweltering with the heat, we all sat down for a moment’s rest and enjoyment. We love water, especially water in motion, with an inexpressible fondness; and as we passed on, we paused for a moment at the end of the bridge to take a last look at the cascades, and then went on our way repeating Tennyson’s noble line,

- ‘A thing of beauty is a joy forever.’

- “Toiling up the hill, we found ourselves, almost without knowing it, on Montgomery Place, the residence of Mrs. Barton. This has been so often described, that it seems almost unnecessary to saw a word about it. Its fame is known every where. It is, no doubt, one of the most finished places in the country. It has age; the trees and shrubs have developed all their grand proportions, and impress one with a feeling of reverence. The grouping is well done, and worthy of study. There are many individual specimens of great beauty and interest. The lawn is extensive and well kept. The views are possessed of much grandeur, but might be improved, were it not almost a sacrilege to fell such noble trees. The walks and drives are well made and admirably kept. The Pinetum, though not as large as we could wish, is a very interesting feature. At the conservatory we found Alexander, and locum tenens [substitute owner] of the place. Alexander was born and brought up here. He is very polite and attentive, and takes a good deal of pride, as well he may, in pointing out objects of interest. The conservatory is a ridge and furrow house of large dimensions, and was filled with Fuchsias, Gloxinias, Achimenes, Hanging Baskets, and variegated leafed plants of great variety. All were well grown, and the house was gay with flowers. The flower garden is a fine piece of work, but the arrangement of the bedding plants a little faulty. The plants themselves, however, were mostly in good condition, and the whole garden clean and tidy. Perhaps the finest trees on Montgomery Place are the Elms; but we must not particularize; we have no time for that now. A person should hardly visit Montgomery Place unless he can spend a day there, and repeat his visit often: a mere glance at so many grand things only serves to bewilder one. But this was all we could do, and so we passed along to ‘Messina,’ the home of Mr. Aspinwall.”

- Lossing, Benson J., 1860, “The Hudson, from the Wilderness to the Sea” (The Art-Journal 6, [London]: 304) Back up to History

- “The wife of Montgomery was a sister of Chancellor Livingston. With ample means and good taste at command, she built this mansion, and there spent fifty years of widowhood, childless, but cheerful. The mansion and its 400 acres passed into the possession of her brother Edward, and there, as we have observed, his family now reside. Of all the fine estates along this portion of the Hudson, this is said to be the most perfect in its beauty and arrangements. Waterfalls, picturesque bridges, romantic glens, groves, a magnificent park, one of the beautiful of the ornamental gardens in this country, and views of the river and mountains, unsurpassed, render Montgomery Place a retreat to be coveted, even by the most favoured of fortune.”

- Henderson, Peter, 1869, “Notices of New and Interesting Bedding and Other Plants Tested in 1868” (American Horticultural Annual: 112) Back up to History

- “Achyranthes Verschaffeltii, var. Gilsoni. – The great fault with the original species was the dull crimson shade, inferior to Coleus and other plants of dark foliage; but in the variety Gilsoni, the color of the leaves is a carmine rather than a crimson, with the stems of a deep shade of pink, giving to the plant a bright and lively appearance, far surpassing the old variety; it is also of dwarfer and denser growth, and is an improvement so decided that it will, without doubt, throw the original one out of cultivation. We grew them side by side during the past summer, and the superiority of this was apparent to all who saw them. As I write, (14th October), it is one of the most attractive plants in our grounds. The merit of originating this valuable plant is due to Alexander Gilson, gardener to Mrs. Cora L. Barton, Barryton, N.Y.”

- Kennedy, Alexander, March 27, 1897, letter to the editor in “The Roll of Honor” (American Gardening 18, no. 118: 227)

- “In regard to Aschyranthus Gilsonii, would may say that the raiser of it was Alexander Gilson, a colored man and well worthy to bear the title of gardener. I was a neighbor of his and knew him well. It was about the year 1872 that he raised the Aschyranthus. He was then the gardener for Mme. Livingstone, and afterward for her successor, Mrs. Barton, on what was called “the Montgomery place,” once the country residence of General Montgomery, from which it took its name. It is located in the town of Red Hook, Dutchess county, N.Y.”

- Lown, Frank B., March 27, 1897, letter to the editor in “The Roll of Honor” (American Gardening 18, no. 118: 227)

- “I am particularly interested in one name in your 'Roll of Honor,' [of outstanding plants] and that is Aschyranthus Gilsonii, which you say was raised by a colored gardener. When I was a child I lived in Barrytown … and I well remember Alexander Gilson, who was then the gardener on what was known as the ‘Barton place,’ a couple of miles north of where we lived. He was a colored man, but he very justly earned and received the cordial liking and respect of the entire community. He was an accomplished gardener, and died but only a few years ago, and I am rejoiced to know that now the name of old ‘Alexander’—for no one knew him as aught else— has been perpetuated by the plant referred to in your speech.”

Images

Other Resources

xxx

Notes

- ↑ A. J. Downing, "A Visit to Montgomery Place," Horticulturist 2, no. 4 (October 1847), view on Zotero.