Difference between revisions of "Wall"

m (copyedits) |

|||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

[[File:0121.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 3, Alexander Francis, ''Ralph Wheelock's Farm'', c. 1822.]] | [[File:0121.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 3, Alexander Francis, ''Ralph Wheelock's Farm'', c. 1822.]] | ||

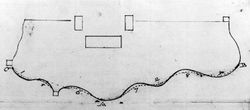

| − | [[File:1432.jpg|thumb|Fig. 4, Milo Osborne, | + | [[File:1432.jpg|thumb|Fig. 4, Milo Osborne, “Deaf and Dumb Asylum,” in Theodore S. Fay, ''Views in New-York and its Environs from Accurate, Characteristic, and Picturesque Drawings'' (1831).]] |

| − | As [[J. C. Loudon]] noted in 1834, walls were generally composed of three sections: the foundation, the body formed by courses of stone or brick, and, if desired, the coping (a decorative or protective course on top of a masonry wall). Foundations varied from a single course to a three-foot, below-ground stone foundation, such as the one used for the hog yard at Waldwic Cottage (formerly Little Hermitage), described by [[William Ranlett]] (1851). The coping could consist of the same material as the wall, as seen in John William Hill’s 1847 painting of Blandford Church in Petersburg, Va. [Fig. 1], or could be built of contrasting material such as stone or marble, which was used at St. Philip’s Parish in Charleston, | + | As [[J. C. Loudon]] noted in 1834, walls were generally composed of three sections: the foundation, the body formed by courses of stone or brick, and, if desired, the coping (a decorative or protective course on top of a masonry wall). Foundations varied from a single course to a three-foot, below-ground stone foundation, such as the one used for the hog yard at Waldwic Cottage (formerly Little Hermitage), described by [[William Ranlett]] (1851). The coping could consist of the same material as the wall, as seen in John William Hill’s 1847 painting of Blandford Church in Petersburg, Va. [Fig. 1], or could be built of contrasting material such as stone or marble, which was used at St. Philip’s Parish in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1826. William Forsyth recommended wooden coping in order to attach nets that would discourage birds from eating nearby fruit.<ref>William Forsyth, ''A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees'' (Philadelphia: J. Morgan, 1802), 150, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/ZSNDFTE9/ view on Zotero]. </ref> Walls were sometimes topped with palisades, which extended their height and deterred intruders while providing a visually permeable barrier. This feature provided additional ornament, as the ironwork palisade on the wall at the Governor’s House in New York [Fig. 2] demonstrates. |

| − | [[File:0168.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 5, Thomas Jefferson, Third variant for range and gardens, showing serpentine walls at the University of Virginia, c. | + | [[File:0168.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 5, Thomas Jefferson, Third variant for range and gardens, showing serpentine walls at the University of Virginia, c. 1817–22.]] |

| − | [[File:0112.jpg|thumb|Fig. 6, [[Anthony St. John Baker]], | + | [[File:0112.jpg|thumb|Fig. 6, [[Anthony St. John Baker]], “View of the White House,” 1826, in ''Mémoires d’un voyageur qui se repose'' (1850).]] |

| − | The choice of materials for the body of the wall depended upon its use and upon the materials that were available. In arid regions, particularly areas with Spanish building traditions, adobe was frequently used. <ref>For an analysis of the function and significance of walls and gates in Latin American vernacular architecture, and particularly in the enclosure of the patio garden, see William J. Siembieda, “Walls and Gates: A Latin Perspective,” ''Landscape Journal'' 15 ( | + | The choice of materials for the body of the wall depended upon its use and upon the materials that were available. In arid regions, particularly areas with Spanish building traditions, adobe was frequently used.<ref>For an analysis of the function and significance of walls and gates in Latin American vernacular architecture, and particularly in the enclosure of the patio garden, see William J. Siembieda, “Walls and Gates: A Latin Perspective,” ''Landscape Journal'' 15 (Fall 1996): 113–32, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/RPIU68EV view on Zotero].</ref> Stone walls were common in New England, where field stones turned up by plows provided ready material for dry laid walls, as that depicted in the painting of Ralph Wheelock’s farm in Pennsylvania (1822) [Fig. 3].<ref>Wilbur Zelinsky cites in 1871 that the Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture included data for fence types in New England. The frequency of stone fences ranged from 32 percent in Vermont to a high of 79 percent in Rhode Island. See Ervin H. Zube and Margaret J. Zube, eds., ''Changing Rural Landscapes'' (1951; repr., Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1977), 59, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/X8FV99J7 view on Zotero].</ref> It has been suggested that wall designs from British treatise and pattern books, such as those published in [[Batty Langley]]’s ''The City and Country Builder’s and Workman’s Treasury of Designs'' (1740), were reworked in wood in the American context. Wooden posts were used in place of piers, wooden members in place of stone fenestration, and baseboards in place of stone bases.<ref>Philip Dole, “The Picket Fence at Home,” in ''Between Fences'', ed. Gregory K. Dreicer (Washington, DC: National Building Museum, 1996), 28–30, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/GG78VBCM view on Zotero].</ref> The earthen- and pitch-covered wooden walls described by Loudon do not appear to have been employed in America, but fence posts were tarred as a preservative measure. |

Walls, like related features such as [[fence]]s, [[hedge]]s, and [[ha-ha]]s, served as barriers, supports, and markers of property boundaries. Because of their strength, walls were also used to retain earth; this use is illustrated by the deer wall at [[Mount Vernon]] (1798) and the [[terrace]] wall at the Deaf and Dumb Asylum in New York [Fig. 4]. Walls were also used to shore up banks at waterfront gardens, as at [[Westover]] in Virginia, described by Thomas Lee Shippen (1783), where they served as bulkheads along the banks of the James River. | Walls, like related features such as [[fence]]s, [[hedge]]s, and [[ha-ha]]s, served as barriers, supports, and markers of property boundaries. Because of their strength, walls were also used to retain earth; this use is illustrated by the deer wall at [[Mount Vernon]] (1798) and the [[terrace]] wall at the Deaf and Dumb Asylum in New York [Fig. 4]. Walls were also used to shore up banks at waterfront gardens, as at [[Westover]] in Virginia, described by Thomas Lee Shippen (1783), where they served as bulkheads along the banks of the James River. | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

While the practical functions of walls were much discussed, they also made significant aesthetic contributions to landscape design. [[Philip Miller]] suggested in 1759 that walls be disguised with “[[Plantation]]s of Flowering Shrubs, intermixed with laurels, and some evergreens.” [[Thomas Bridgeman]] (1832), [[Edward Sayers]] (1838), and [[A. J. Downing]] (1849) all suggested the use of creeping vines and [[trellis]]es to incorporate the wall into a naturalistic or [[picturesque]] garden setting. | While the practical functions of walls were much discussed, they also made significant aesthetic contributions to landscape design. [[Philip Miller]] suggested in 1759 that walls be disguised with “[[Plantation]]s of Flowering Shrubs, intermixed with laurels, and some evergreens.” [[Thomas Bridgeman]] (1832), [[Edward Sayers]] (1838), and [[A. J. Downing]] (1849) all suggested the use of creeping vines and [[trellis]]es to incorporate the wall into a naturalistic or [[picturesque]] garden setting. | ||

| − | Unlike worm and wire [[fence]]s, a wall was a decidedly immovable barrier. Its permanence, durability, and scale made it particularly suitable to the monumental and stately requirements of churchyards, [[cemeteries]], and [[public ground]]s, as noted in a 1770 description of the Annapolis Parade and as depicted in a [[view]] of the [[White House]] in Washington, | + | Unlike worm and wire [[fence]]s, a wall was a decidedly immovable barrier. Its permanence, durability, and scale made it particularly suitable to the monumental and stately requirements of churchyards, [[cemeteries]], and [[public ground]]s, as noted in a 1770 description of the Annapolis Parade and as depicted in a [[view]] of the [[White House]] in Washington, DC [Fig. 6]. [[J.C. Loudon|Loudon]] in 1834 described walls as the “grandest [[fence]]s for [[park]]s,” although images of American urban parks suggest that by the second quarter of the 19th century ironwork [[fence]]s were the enclosures of choice. In urban settings, walls provided residents with a visual screen from what lay beyond [Fig. 7] and, although not noted in descriptions, they probably served as an effective noise barrier as well. Walls were also used to ornament the front approaches to houses. An over-mantle painting of a house in Fairfield, Connecticut, illustrates a more decorative treatment of a wall directly in front of the house in contrast to walls and [[fence]]s on other parts of the property [Fig. 8]. A well-kept wall came to signify the prosperity and good management of the farmer, and, as [[Timothy Dwight]] noted in 1796, such walls were “the image of tidy, skilful, profitable agriculture.” |

| − | + | —''Elizabeth Kryder-Reid'' | |

==Texts== | ==Texts== | ||

Revision as of 17:01, February 22, 2018

See also: Botanic garden, Espalier, Fence, Greenhouse, Kitchen garden, Orchard

History

In American landscape design, the wall was a masonry construction of dry laid or mortared stone or brick. While treatises and dictionaries often referred to walls as a type of fence and sometimes as a “stone fence,” in American usage, wooden barriers were referred to exclusively as fences.

As J. C. Loudon noted in 1834, walls were generally composed of three sections: the foundation, the body formed by courses of stone or brick, and, if desired, the coping (a decorative or protective course on top of a masonry wall). Foundations varied from a single course to a three-foot, below-ground stone foundation, such as the one used for the hog yard at Waldwic Cottage (formerly Little Hermitage), described by William Ranlett (1851). The coping could consist of the same material as the wall, as seen in John William Hill’s 1847 painting of Blandford Church in Petersburg, Va. [Fig. 1], or could be built of contrasting material such as stone or marble, which was used at St. Philip’s Parish in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1826. William Forsyth recommended wooden coping in order to attach nets that would discourage birds from eating nearby fruit.[1] Walls were sometimes topped with palisades, which extended their height and deterred intruders while providing a visually permeable barrier. This feature provided additional ornament, as the ironwork palisade on the wall at the Governor’s House in New York [Fig. 2] demonstrates.

The choice of materials for the body of the wall depended upon its use and upon the materials that were available. In arid regions, particularly areas with Spanish building traditions, adobe was frequently used.[2] Stone walls were common in New England, where field stones turned up by plows provided ready material for dry laid walls, as that depicted in the painting of Ralph Wheelock’s farm in Pennsylvania (1822) [Fig. 3].[3] It has been suggested that wall designs from British treatise and pattern books, such as those published in Batty Langley’s The City and Country Builder’s and Workman’s Treasury of Designs (1740), were reworked in wood in the American context. Wooden posts were used in place of piers, wooden members in place of stone fenestration, and baseboards in place of stone bases.[4] The earthen- and pitch-covered wooden walls described by Loudon do not appear to have been employed in America, but fence posts were tarred as a preservative measure.

Walls, like related features such as fences, hedges, and ha-has, served as barriers, supports, and markers of property boundaries. Because of their strength, walls were also used to retain earth; this use is illustrated by the deer wall at Mount Vernon (1798) and the terrace wall at the Deaf and Dumb Asylum in New York [Fig. 4]. Walls were also used to shore up banks at waterfront gardens, as at Westover in Virginia, described by Thomas Lee Shippen (1783), where they served as bulkheads along the banks of the James River.

The vast majority of treatise references to walls discuss their use as supports and protection for fruit trees in orchards and fruit gardens. The length and detail of the instructions suggest the importance of walls as an adaptation to the range of American climatic challenges for fruit growers. A brick wall reflected heat during the day and retained warmth at night, providing a moderating micro-climate and promoting earlier ripening. Fruit walls for “forwarding” the fruit season were useful in the middle and eastern states, but they were not necessary in warmer climates. Brick walls with flues, discussed in detail in numerous treatises, were used in hothouse and conservatory construction (see also Greenhouse. Trellises for training trees and vines were easily attached to brick walls’ porous surfaces. Bricks’ porosity also helped them retain heat much better than stone, even when the stone was painted a dark color. In the rare instance when stone was used, authors suggested that it be faced with several courses of brick on the side on which fruit trees were to be grown.

Most walls were straight, although the merits of serpentine walls were debated in the literature. Some authors, such as Ephraim Chambers (1741–43), argued that the serpentine wall was strong and economical, requiring less thickness to maintain the same strength as a straight wall. These walls also could be used to shelter plants from winds coming from all directions. Thomas Jefferson used a serpentine wall for the faculty gardens at the University of Virginia [Fig. 5]. Others, such as Loudon (1834) and George William Johnson (1847), criticized the serpentine form, arguing that such walls had to be too thick to retain the necessary heat for fruit ripening.

While the practical functions of walls were much discussed, they also made significant aesthetic contributions to landscape design. Philip Miller suggested in 1759 that walls be disguised with “Plantations of Flowering Shrubs, intermixed with laurels, and some evergreens.” Thomas Bridgeman (1832), Edward Sayers (1838), and A. J. Downing (1849) all suggested the use of creeping vines and trellises to incorporate the wall into a naturalistic or picturesque garden setting.

Unlike worm and wire fences, a wall was a decidedly immovable barrier. Its permanence, durability, and scale made it particularly suitable to the monumental and stately requirements of churchyards, cemeteries, and public grounds, as noted in a 1770 description of the Annapolis Parade and as depicted in a view of the White House in Washington, DC [Fig. 6]. Loudon in 1834 described walls as the “grandest fences for parks,” although images of American urban parks suggest that by the second quarter of the 19th century ironwork fences were the enclosures of choice. In urban settings, walls provided residents with a visual screen from what lay beyond [Fig. 7] and, although not noted in descriptions, they probably served as an effective noise barrier as well. Walls were also used to ornament the front approaches to houses. An over-mantle painting of a house in Fairfield, Connecticut, illustrates a more decorative treatment of a wall directly in front of the house in contrast to walls and fences on other parts of the property [Fig. 8]. A well-kept wall came to signify the prosperity and good management of the farmer, and, as Timothy Dwight noted in 1796, such walls were “the image of tidy, skilful, profitable agriculture.”

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Fitzhugh, William, April 1686, describing Greensprings, Va. (quoted in Lockwood 1934: 2:46) [5]

- “the Plantation where I now live contains a thousand acres, grounds and fencing . . . a large orchard of about 2500 Apple trees most grafted, well fenced with a locust fence, which is as durable as most brick walls, a Garden, a hundred foot square, well pailed in, a Yeard wherein is most of the aforesaid necessary houses, pallizad’d in with locust Punchens which is as good as if it were walled in and more lasting than any of our bricks.”

- Anonymous, 8 May 1704, describing in the Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia the construction in Williamsburg, Va. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; hereafter CWF)

- “Ordered. That the consideration of the proposall of the said Committee relating, [sic] to the Capitol being inclosed with a brick wall be referred til tomorrow morning. Ordered. That the Overseer appointed to inspect and oversee the building of the Capitol make a Computation what the Charges may amount to of inclosing the Capitol with a Brick Wall of two Bricks thick and four feet and a half high to be distant sixty foot from the fronts of the East and West Building and the said building and that he lay the same before the House to morrow.”

- Washington, George, 27 March 1760, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, Va. (quoted in Johnson 1953: 75) [6]

- “Agreed to give Mr. William Triplet, 18 to build the two houses in the Front of my House (plastering them also), and running walls for Pallisades to them from the Great house and from the Great House to the Wash House and Kitchen also.”

- Bartram, John, 3 December 1762, describing Charleston, S.C. (quoted in Darlington 1849: 242–43) [7]

- “I can’t find, in our country, that south walls are much protection against our cold, for if we cover so close as to keep out the frost, they are suffocated.”

- Anonymous, 4 January 1770, describing the State House, Annapolis, Md. (Maryland Gazette)

- “The General Assembly having been pleased to grant to the Value of 7500 l. Sterling, for building a State-House . . . and for enlarging, repairing, and enclosing the Parade, not exceeding its present Length of 245 feet, and 160 in Breadth, designed to be enclosed with Stone or Brick Wall, and Iron Palisadoes, if the Iron Inclosure should not exceed 500 Sterling.”

- Chastellux, François Jean Marquis de, 1780–82, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd III, on the James River, Va. (1787: 2:172) [8]

- “The walls of the garden and the house were covered with honey-suckles.”

- Shippen, Thomas Lee, 30 December 1783, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd III, on the James River, Va. (1952: n.p.) [9]

- “the river is backed up by a wall of four feet high, and about 300 yards in length, and above this wall there is as you may suppose the most enchanting walk in the world.”

- Morse, Jedidiah, 1789, describing the State House Yard, Philadelphia, Pa. ([1789] 1970: 331) [10]

- “The state house yard, is a neat, elegant and spacious public walk, ornamented with rows of trees; but a high brick wall, which encloses it, limits the prospect.”

- Bentley, William, 3 October 1789, describing the Collins and Ingersoll Gardens, Salem, Mass. (1962: 1:127) [11]

- “Capt Collins laid the foundation of his new Sea Wall which makes his garden square at the bottom of Turner’s Lane, on the east side. Capt. S. Ingersoll on Turner’s Estate has added a new picketed fence to his excellent stone wall, which gives a good appearance.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing Worcester County, Mass. (1821: 1:375) [12]

- “In no part of this country are the barns universally so large, and so good; or the inclosures of stone so general, and every where so well formed. These inclosures are composed of stones, merely laid together in the form of a wall, and not compacted with mortar. . . . This relative beauty these enclosures certainly possess: for they are effectual, strong, and durable. Indeed where the stones have a smooth regular face, and are skilfully laid in an exact line, with a true front, the wall independently of this consideration, becomes neat, and agreeable. A farm well surrounded, and divided, by good stone-walls, presents to my mind, irresistibly, the image of tidy, skilful, profitable agriculture; and promises to me within doors, the still more agreeable prospect of plenty and prosperity.”

- Washington, George, October 1798, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, Va. (Mount Vernon Ladies Association)

- “Supposing the dot at A to be the highest part of the hill in front of the House. & at the black line from B to C by A the natural shape of the hill (or fall of the hill) the pricked line may be a good direction for the wall, in order to prevent its being too serpentine or crooked—this, in some places, will come in upon the level (or that which is nearly so) of the hill—as at 1, 2, 3—and is often as at 5, 6, 7 & 8 will be below the declivity, & require filling up in order to bring the whole to a level which is to be affected by the Earth which may be taken from 1, 2, 3.—

- “There are two reasons for doing it in this manner—the one is, to prevent the wall from being too serpentine & crooked (as the black line)—and the second is, that the hill below the wall may be more of a sameness.—otherwise it would descend very suddenly in some places and very gradually in others.—

- “You will observe that this wall is not to be laid out, as worked by a line—the whole of it is serpentine, which I am particular in mentioning least by the expression in your letter of zig-zag. You had an idea that it was to be laid out by line 20 or 30 feet or yards (as the hill would admit) one way then angling & as far as it would go strait another in the following manner.” [Fig. 9]

- Adams, Abigail, 1800, describing the Peacefield, estate of John Adams, Quincy, Mass. (quoted in Hammond 1982: 182) [13]

- “the President has authorised me to have a number of Lombardy poplars set out opposite the house near the wall which was new just two years ago. . . . he says he will have them extended from the gate . . . to the corner.”

- Ogden, John Cosens, 1800, describing a graveyard in Bethlehem, Pa. (p. 15) [14]

- “It is surrounded partly with a stone wall, towards the street, where it cannot be enlarged, partly with a neat wooden fence, on those sides where it may be extended from time to time.”

- Scott, Joseph, 1806, describing a public prison in Philadelphia, Pa. (p. 46) [15]

- “The yard belonging to the criminal prison extends nearly to Prune street, on which is the debtors’ apartment. The whole is surrounded by a lofty stone wall.”

- Drayton, Charles, November 2, 1806, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamitlon, near Philadelphia, Pa. (1806: 55–58)[16]

- "The Conservatory consists of a green house, & 2 hot houses—one being at each end of it. The green house may be about 50 feet long. The front only is glazed. Scaffolds are erected, one higher than another, on which the plants in pots or tubs are placed—so that it is representing the declivity of a mountain. At each end are step-ladders for the purpose of going on each stage to water the plants—& to a walk at the back-wall. On the floor a walk of 5 or 6 feet extends along the glazed wall & at each end a door opens into an Hot house—so that a long walk extends in one line along the stove walls of the houses & the glazed wall of the green house.

- "The Hot houses, they may extend in front, I suppose, 40 feet each. They have a wall heated by flues—& 3 glazed walls & a glazed roof each. In the center, a frame of wood is raised about 2 1/2 feet high, & occupying the whole area except leaving a passage along by the walls. In the flue wall, or adjoining, is a cistern for tropic aquatic plants. Within the frame, is composed a hot bed; into which the pots & tubs with plants, are plunged. This Conservatory is said to be equal to any in Europe. It contains between 7 & 8000 plants. To this, the Professor of botany is permitted to resort, with his Pupils occasionally. . . .

- ". . . .From the Cellar one enters under the bow window & into this Screen, which is about 6 or 7 feet square. Through these, we enter a narrow area, & ascend some few Steps [close to this side of the house,] into the garden—& thro the other opening we ascend a paved winding slope, which spreads as it ascends, into the yard. This sloping passage being a segment of a circle, & its two outer walls concealed by loose hedges, & by the projection of the flat roofed Screen of masonry, keeps the yard, & I believe the whole passage out of sight from the house—but certainly from the garden & park lawn."

- Stebbins, William, 6 February 1810, describing the White House, Washington, D.C. (1968: 37) [17]

- “Extended my walk alone to the President’s House:—a handsome edifice, tho’ like the capitol of free stone: the south yard principally made ground, bank’d up by a common stone wall.”

- Hosack, David, 1811, describing the establishment of the Elgin Botanic Garden, New York, N.Y. (pp. 10, 15) [18]

- “Accordingly, in the following year, 1801, I purchased of the corporation of the city of New York twenty acres of ground. . . .

- “At a considerable expense, the establishment was inclosed by a well constructed stone wall....

- “The whole establishment was enclosed by a stone wall, two and an half feet in breadth, and seven and an half feet high.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, 15, 27, 29 March 1814, in a letter to his sons, Benjamin Franklin Peale and Titian Ramsey Peale, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, Pa. (Miller, Hart, and Ward, eds., 1991: 3:239) [19]

- “The stone and ground is remooved at the Bottom of the Garden but the Wall is not as high and access into the Garden is not so easey as it used to be, even before any wall is made.”

- Bryant, William Cullen, 25 August 1821, describing the Vale, estate of Theodore Lyman, Waltham, Mass. (1975: 108) [20]

- “He took me to the seat of Mr. Lyman. . . . It is a perfect paradise. . . . A hard rolled walk, by the side of a brick wall, about ten feet in height and covered with peach and apricot espaliers which seemed to grow to it, like the creeping sumach to the bark of an elm.”

- Hunt, Henry, Wm. P. Elliot, and William Thornton, 1826, requesting a Memorial to the House of Representatives of the Congress in Washington, D.C. (U.S. Congress, 19th Congress, 1st Session, House of Representatives, doc. 123, book 138)

- “That, with a view to promote the public good, and to ornament and improve the public grounds, they would recommend . . . That a wall five feet high, with a stone coping, be put round the ground appropriated for a Botanic Garden.”

- Anonymous, 16 July 1826, describing in the St. Philip’s Parish Vestry Book meeting resolutions made in Charleston, S.C. (CWF)

- “The Vestry inform the Meeting that they have entered into an agreement with Corporation of the City to take down the present old brick walls around the church, on Church Street, and to erect in its place a low wall of brick to be capped with marble and finished with an iron pallisade and three iron gates.”

- Viator [pseud.], 15 August 1828, “Nurseries and Gardens on Long Island,” describing André Parmentier’s horticultural and botanical garden, Brooklyn, N.Y. (New England Farmer 7: 25)

- “At Brooklyn we called at the celebrated Horticultural Garden of Mr. ANDRE PARMENTIER. This is a recent establishment begun in 1825. It contains 20 acres, and is surrounded by a wall of masonry, after the manner which we are told is practised on the old continent.”

- Breck, Joseph, 1 February 1836, “Gardens, Hothouses, &c., in the vicinity of Boston,” describing Bellmont Place, residence of John Perkins Cushing, Watertown, Mass. (Horticultural Register 2: 43–44) [21]

- “The garden is a square, level plot, bounded on the north side by the conservatories, which, if we are not mistaken, are four hundred feet in length. On the east and west are high, substantial brick walls, to which are trained a choice collection of fruit trees imported the last season, already formed for the purpose, some of which are protected by glass. The southern wall is very ornamental and substantial, and so low that the whole area and houses may be seen at a single glance outside the wall.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., 1841, describing the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, Pa. (1851: 17) [22]

- “PLEASURE GROUND AND FARM.—Of the one hundred and eleven acres in the farm, about forty-one around the Hospital are specially appropriated as a vegetable garden and the pleasure ground of the patients, and are surrounded by a substantial stone-wall. This wall is five thousand four hundred and eighty-three feet long, and is ten and a half feet high.

- “Owing to the favourable character of the ground, the wall has been so placed that it can be seen but in a very small part of its extent, from any one position; and the enclosure is so large, that its presence exerts no unpleasant influence upon those within. Although it is probably sufficient to prevent the escape of a large proportion of the patients, that is a matter of small moment, in comparison with the quiet and privacy which it at all times affords, and the facility with which the patients are enabled to engage in labour, to take exercise, or to enjoy the active scenes which are passing around them, without fear of annoyance from the gaze of idle curiosity or the remarks of unfeeling strangers.”

- Smith, Margaret Bayard, 1841, describing the White House, Washington, D.C. (1906: 393) [23]

- “He [[[Thomas Jefferson]]] was very anxious to improve the ground around the President’s House; but as Congress would make no appropriation for this and similar objects, he was obliged to abandon the idea, and content himself with enclosing it with a common stone wall and sewing it down in grass.” [See Fig. 6]

- Mills, Robert, 23? February 1841, describing the national Mall, Washington, D.C. (Scott, ed., 1990: n.p.) [24]

- “A range of trees is proposed to surround three sides of the square which is intended to be laid open by an iron or other railing, the north side to be enclosed with a high brick wall to serve as a shelter and to secure the various hot houses and other buildings of an inferior character.”

- Trego, Charles, 1843, describing Harrisburg, Pa. (p. 233) [25]

- “These public buildings stand in a large enclosure, planted with trees, and surrounded by a brick wall on which is a neat paling.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., April 1848, describing the pleasure grounds and farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, Pa. (American Journal of Insanity 4: 347) [26]

- “As much as possible of the grounds belonging to a hospital for the insane should be permanently enclosed by a substantial wall of stone or brick. This wall should always be so arranged as in at least a considerable part of its extent, to be completely out of view from the buildings, either by being placed in low ground, if that is practicable, or if not, it can readily be arranged by being sunk in certain places in an artificial trench, and thus to prevent its being an unpleasant feature, or to give the idea of a prison enclosure. Such a wall however, useful as it is, had much better not be put up, unless to enclose a large number of acres, or unless it can be kept from being a prominent object from the buildings.”

- Loudon, J. C., 1850, describing Waltham House at the Vale, estate of Theodore Lyman, Waltham, Mass. (p. 330) [27]

- “844. Waltham House. . . . to the left and rear of the house are the kitchen-garden, grapery, greenhouse, hothouse, wall for fruit, &c. ...(Downing’s Landscape Gardening.)”

- Ranlett, William H., 1851, describing Waldwic Cottage (formerly Little Hermitage), property of Elijah Rosencrantz, Hohokus, N.J. ([1851] 1976: 2:43) [28]

- “hog pen and yard, 20 by 27, with a good substantial stone wall.”

Citations

- Parkinson, John, 1629, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris ([1629] 1975: 537) [29]

- “Having an Orchard containing one acre of ground, two, three, or more, or lesse, walled about, you may so order it, by leaving a broad and large walke betweene the wall and it . . . and by compassing your Orchard on the inside with a hedge (wherein may bee planted all sorts of low shrubs or bushes.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, Cyclopaedia (2:n.p.) [30]

- “WALLS, in gardening, &c.—The position, matter, and form of walls, for fruit-trees, are found to have a great influence on the fruit: though authors differ as to the preference. See GARDEN, ORCHARD, &c.

- “The reverend Mr. Lawrence directs, that the WALLS of a garden be not built directly to face the four cardinal points, but rather between them, viz. south-east, south-west, north-east, and northwest: in which the two former will be good enough for the best fruit, and the two latter for plums, cherries, and baking pears. See EXPOSURE. Mr. Langford, and some others, propose garden-walls to consist chiefly of semicircles; each about six or eight yards in front, and two trees; and between every two semicircles, including-a space of two feet of plain wall.—By such a provision every part of a wall will enjoy an equal share of the sun, one time with another; beside, that the warmth will be increased, by the collecting and reflecting of the rays in the semicircles; and the trees within be screened from injurious winds.

- “As to the materials of walls for fruit-trees, brick, according to Mr. Switzer, is the best; as being the warmest and kindest for the ripening of fruit, and affording the best conveniency for nailing.

- “Mr. Lawrence, however, affirms, on his own experience, that mud-walls, made of earth and straw tempered together, are better for the ripening of fruit, than either brick or stone walls: he adds, that the coping of straw laid on such walls, is of great advantage to the fruit, in sheltering them from perpendicular rains, &c.

- “M. Fatio, in a particular treatise on the subject, instead of the common perpendicular walls, proposes to have the walls built sloping, or reclining from the sun; that what is planted against them, may lie more exposed to his perpendicular rays; which must contribute greatly to the ripening of fruit in our cold climate.”

- Miller, Philip, 1754, The Gardeners Dictionary ([1754] 1969: 1505–14) [31]

- “WALLS are absolutely necessary in Gardens, for the ripening of all such Fruits as are too delicate to be perfected in this Country, without such Assistantce. These are built with different Materials; in some Countries they are built of Stone, in others with Brick, according as the Materials can be procured best and cheapest.

- “Of all Materials proper for building Walls for Fruit-trees, Brick is the best; in that it is not only the handsomest, but the warmest and kindest for the ripening of Fruit; besides that, it affords the best Conveniency of Nailing. . . .

- “Where the Walls are built intirely of Stone, there should be Trelases fix’d up against them, for the more convenient fastening of the Branches of the Trees. . . .

- “There have been several Trials made of Walls built in different Forms; some of them having been built semicircular, others in Angles of various Sizes, and projecting more toward the North, to screen off the cold Winds: but there has not been any Method as yet, which has succeeded near so well, as that of making the Walls strait, and building them upright. . . .

- “According to the modern Taste in Gardening, there are very few Walls built round Gardens; which is certainly very right, not only with regard to the Pleasure of viewing the neighbouring Country from the Garden, but also in regard to the Expence, 1. Of building these Walls: 2. If they are planted with Fruit, as is frequently practised, to maintain them will be a constant Charge . . . therefore the Quantity of Walling should be proportion’d to the Fruit consumed in the Family: but as it will be necessary to inclose the Kitchen-garden, for the Security of the Garden-stuff, so, if that be walled round, it will contain as much Fruit as will be wanted in the Family. ...

- “In the building of the Walls round a Kitchen-garden, the Insides, which are design’d to be planted with Fruit-trees, should be made as plain as possible, so that the Piers should not project on those Sides above four Inches at most. . . .

- “The usual Thickness which Garden-walls are allow’d, if built with Bricks, is thirteen Inches, which is one Brick and an half: but this should be proportionable to the Height. . . .

- “But I shall now proceed to give some Directions for the building of Hot-walls, to promote the ripening of Fruits, which is now pretty much practis’d in England.

- “In some Places these Walls are built at a very great Expence, and so contriv’d as to consume a great Quantity of Fuel; but where they are judiciously built, the first Expence will not be near so great, nor will the Charge of Fuel be very considerable. . ..

- “The ordinary Height of these Hot-walls is about ten Feet, which will be sufficient for any of those Sorts of Fruits which are generally forced. . . .

- “The Foundations of these Walls should be made four Bricks and an half thick, in order to support the Flues; otherwise, if Part of them rest on Brick-work, and the other on the Ground, they will settle unequally, and soon be out of Order. . . .

- “The Ovens in which the Fires are made, must be contrived on the Back-side of the Walls, which should be in Number proportionable to the Length of the Walls....

- “The Borders in Front of these Hot-walls should be about four Feet wide, which will make sufficient Declivity for the sloping Glasses. . . . On the Outside of these Borders should be low Walls erected, which should rise an Inch or two above the Level of the Borders; upon which the Plate of Timber should be laid, on which the sloping Glasses are to rest: and this Wall will keep up the Earth of the Border, as also preserve the Wood from rotting.”

- Ware, Isaac, 1756, A Complete Body of Architecture (pp. 641, 649) [32]

- “When a garden is already made in an ill spot, all that can be done is to open agreeable views by clearing away walls and hedges in the ground; and trees, and sometimes even buildings, when ill-placed, ill-looking and of little value: this is to be done when something pleasing, some view of elegant, wild nature can be let in; and where that cannot be, some pavilion, such as we have described, or shall describe, must shut out unalterable deformity.”

- “Extent and freedom we have directed largely. He who builds high walls about a small garden must climb to his summer-house: this we have named with due contempt. . . .

- “This closeness of a garden is one of the first things against which a person of any degree of taste will resolve.”

- Miller, Philip, 1759, The Gardeners Dictionary (n.p.) [33]

- “Another thing absolutely necessary is where the Boundaries of the Garden are fenced with Walls or Pales, they should be hid by Plantations of Flowering Shrubs, intermixed with laurels, and some Evergreens, which will have a good effect, and at the same time conceal the fences which are disagreeable, when left naked and exposed to the Sight.”

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.) [34]

- “WALL, wa’l. s. A series of brick or stone carried upwards and cemented with mortar. . . .

- “WALLFRUIT, wa’l-frot. s. Fruit which, to be ripened, must be planted against a wall.”

- Deane, Samuel, 1790, The New-England Farmer (pp. 88–89) [35]

- “FENCE, a hedge, wall, ditch, or other enclosure made about farms, or parts of farms, to exclude cattle, or include them. Fencing is a matter of great consequence with farmers. . . .

- “When ground is wholly subdued, and the stumps of its original growth of trees quite rotted out, if stones can be had without carrying too far, stone walls are the fences that ought to be made. Though the cost may be greater at first than that of some other fences, they will prove to be cheapest in the end.”

- Forsyth, William, 1802, A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees (pp. 146–47, 150) [36]

- “It [a garden] should be walled round with a brick wall from ten to twelve feet high: But, if there be plenty of walling, which there may be when you are not stinted with respect to ground, I would prefer walls ten feet high, to those that are higher, and I am convinced they will be found more convenient. . . .

- “By making slips on the outside of the garden wall, you will have plenty of ground for gooseberries, currants, strawberries &c. You may allot that part of the slips which lies nearest to the stables . . .for melon and cucumber beds; and you can plant both sides of the garden-wall....

- “Walls of kitchen gardens should be from ten to fourteen feet high; the foundation should be two bricks or two bricks and a half thick; the offset should not be above one course higher than the level of the border; and the wall should then set off a brick and a half thick. If the walls are long, it will be necessary to strengthen them with piers from forty to sixty feet apart; and these piers should not project above half a brick beyond the wall.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (p. 57) [37]

- “The [pleasure] ground should be previously fenced, which may be occasionally a hedge, paling or wall, &c. as most convenient.”

- Gregory, G., 1816, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (n.p.) [38]

- “[vol. 2] GARDENING. . . .

- “The situation of a garden should be dry, but rather low than high, and as sheltered as can be from the north and east winds. These points of the compass should be guarded against by high and good fences; by a wall of at least ten feet high; lower walls do not answer so well for fruit-trees, though one of eight may do. A garden should be so situated, to be as much warmer as possible than the general temper of the air is without, or ought to be made warmer by the ring and subdivision fences. This advantage is essential to the expectation we have from a garden locally considered. . . .

- “Yet the fall of the leaves by autumnal winds is troublesome, and a high wall is therefore advisable. Spruce firs have been used in close-shorn hedges; which, as evergreens, are proper enough to plant for a screen in a single row, though not very near to the wall; but the best evergreens for this purpose are the evergreen oak and the cork-tree. ...

- “[vol. 3] WALL, in gardening. Of all materials for building walls for fruit-trees, brick is the best, it being not only the handsomest, but the warmest and kindest for the ripening of fruit; and affording the best conveniency for nailing, as smaller nails will serve in brick than will in stone walls, where the joints are larger; and if the walls are caped with free-stone, and stone pilasters or columns at proper distances to separate the trees, and break off the force of the winds; they are very beautiful, and the most profitable walls of any others. In some parts of England there are walls built both of brick and stone, which are found very commodious. The bricks of some places are not of themselves substantial enough for walls; and therefore some persons, that they might have walls both substantial and wholesome, have built these double, the outside being of stone, and the inside of brick; but there must be great care taken to bond the bricks well into the stone, otherwise they are very apt to separate one from the other, especially when frost comes after much wet.

- “There have been several trials made of walls built in different forms; some of them having been built semicircular; others in angles of various sizes; and projecting more towards the north, to screen off the cold winds; but there has not as yet been any method which has succeeded near so well as that of making the walls straight, and building them upright. Where persons are willing to be at the expense in the building of their walls substantial, they will find it answer much better than those which are slightly built, not only in duration, but in warmth; therefore a wall two bricks thick will be found to answer better than that of one brick and a half. The best aspect for ripening fruit is south, with a point to the east; and the next best due south. It is a great improvement to have a trellis of wood against the wall, to train the trees to, as it prevents the wall being spoiled by nails, &c.”

- Gardiner, John, and David Hepburn, 1818, The American Gardener (pp. 136–37) [39]

- “For gardens, hedges are advisable for two distinct purposes: The first, outward fences to serve as a wall for the exclusion of tresspassers [sic]; the other inward, for the purposes of ornament and shade.

- “For the former, the haw-thorn is excellent. . . .

- “For internal ornamental hedges, privet, yew, laurel and box, cedar and juniper, are most generally used.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.) [40]

- “WALL, n. [L. vallum; Sax. weal; D. wal; Ir. Gaelic, balla and fal; Russ. val; W. gwal. In L. vallus is a stake or post, and probably vallum was originally a fence of stakes, a palisade or stockade; the first rude fortification of uncivilized men. The primary sense of vallus is a shoot, or that which is set, and the latter may be the sense of wall, whether it is from vallus, or from some other root.].

- “1. A work or structure of stone, brick or other materials, raised to some highth [sic], and intended for a defense or security. Walls of stone, with or without cement, are much used in America for fences on farms; walls are laid as the foundation of houses and the security of cellars. Walls of stone or brick from the exterior of buildings, and they are often raised round cities and forts as a defense against enemies.”

- Bridgeman, Thomas, 1832, The Young Gardener’s Assistant (p. 134) [41]

- “When Shrubs, Creepers, or Climbers are planted against walls or trellises, either on account of their rarity, delicacy, or to conceal a rough fence or other unsightly object, they require different modes of training.”

- Loudon, J. C., 1834, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 575–80, 615, 728, 1131) [42]

- “2413. Fixed structures consist chiefly of erections for the purpose of improving the climate of plants by shelter, by supplying heat, and by exposing them to the influence of the sun. The genera are walls and espalier rails, of each of which the species are numerous.

- “2414. Garden-walls are formed either of brick, wood, stone, or earth, or brick and stone together; and they are either solid, flued, or cellular, upright or sloping, straight or angular.

- “2415. Brick, stone, or mud walls consist of three parts, the foundation, the body of the wall, and the coping. . . .

- “2416. The brick and stone wall is a stone wall faced with four inches of brick-work, or what is called brick and bed, on the side most exposed to the sun, as on the south sides of east and west walls, and on the insides for the sake of appearance of the two end, or north and south walls of enclosed gardens. . . .

- “2417. The solid brick wall is the simplest of all garden-walls, and where the height does not exceed 6 feet, 9 inches in thickness will suffice; when above that to 13 feet, 14 inches, and when from 13 to 20 feet, 18 inches in width are requisite. . . .

- “2418. The flued wall, or hot-wall. . . is generally built entirely of brick, though where stone is abundant and more economical, the back or north side may be of that material. A flued wall may be termed a hollow wall, in which the vacuity is thrown into compartments (a, a, a, a), to facilitate the circulation of smoke and heat, from the base or surface of the ground to within one or two feet of the coping. . . . A wooden or wire trellis is also occasionally placed before flued walls....

- “2420. The cellular wall (fig. 562.) is a recent invention (Hort. Trans. vol. iv), the essential part of the construction of which is, that the wall is built hollow, or at least with communicating vacuities, equally distributed from the surface of the ground to the coping. . . . The advantages of this wall are obviously considerable in the saving of material, and in the simple and efficacious mode of heating; but the bricks and mortar must be of the best quality. . . . [Fig. 10]

- “2421. Hollow walls may also be formed by using English instead of Flemish bond: that is, laying one course of bricks along each face of the wall on edge, and then bonding them by a course laid across and flat. . . .

- “2422. Where wall-fruit is an object of consideration, the whole of the walls should be flued or cellular, in order that in any wet or cold autumn, the fruit and wood may be ripened by the application of gentle fires, night and day, in the month of September. . . .

- “2423. The mud or earth-wall. . . is formed of clay, or better of brick earth in a state between moist and dry, compactly rammed and pressed together between two moveable boarded sides ... retained in their position by a frame of timber . . . which form, between them the section of the wall . . . these boarded sides are placed, inclining to each other, so as to form the wall tapering as it ascends. . . .

- “2424. Boarded or wooden walls. . . are variously constructed. One general rule is, that the boards of which they are composed, should either be imbricated or close-jointed, in order to prevent a current of air from passing through the seams; and in either case well nailed to the battens behind, in order to prevent warping from serpentine wall. . . has two avowed objects; first, the saving of bricks, as a wall in which the centres of the segments composing the line are fifteen feet apart, may be safely carried fifteen feet high, and only nine inches in thickness from the foundations; and a four-inch wall may be built seven feet high on the same plan. The next proposed advantage is, shelter from all winds in the direction of the wall; but this advantage seems generally denied by practical men. ...

- “2428. The angular wall. . . is recommended on the same general principles of shelter and economy as above; it has been tried nearly as frequently, and as generally condemned on the same grounds. . . .

- “2429. The zig-zag wall (fig. 568.) is an angular wall in which the angles are all right angles, and the length of their external sides one brick or nine inches. This wall is built on a solid foundation, one foot six inches high, and fourteen inches wide. It is then commenced in zig-zag, and may be carried up to the height of fifteen or sixteen feet of one brick in thickness, and additional height may be given by adding three or four feet of brick on edge. . . .

- “2430. The square fret wall. . . is a four-inch wall like the former, and the ground-plan is formed by joining a series of half-squares, the sides of which are each of the proper length for training one tree during two or three years. [Fig. 11]

- “2431. The nurseryman’s, or self-supported four-inch wall. . . is formed in lengths of from five to eight feet, and of one brick in breadth, in alternate planes, so that the points of junction form in effect piers nine by four and a half inches. . . .

- “2432. The piered wall. . . may be of any thickness with piers generally of double that thickness, placed at regular distances, and seldom exceeding the wall in height, unless for ornament. . . .

- “2441. Of fixed structures, the brick wall, both as a fence, and retainer of heat, may be reckoned essential to every kitchen-garden; and in many cases the mode of building them hollow may be advantageously adopted. . . .

- “2617. Walls are unquestionably the grandest fences for parks; and arched portals, the noblest entrances; between these and the hedge or pale, and rustic gate, designs in every degree of gradation, both for lodges, gates, and fences, will be found in the works of Wright, Gandy, Robertson, Aikin, Pocock, and other architects who have published on the rural department of their art. . . .

- “3257. Walls are built round a garden chiefly for the production of fruits. A kitchen-garden, Nicol observes, considered merely as such, may be as completely fenced and sheltered by hedges as by walls, as indeed they were in former times, and examples of that mode of fencing are still to be met with. But in order to obtain the finer fruits, it becomes necessary to build walls, or to erect pales and railings. . . .

- “6380. Fences. Masses, in the ancient style of planting, were generally surrounded by walls or other durable fences. Here the barrier was considered as an object or permanent part of the scene, and for that reason was executed substantially, and even ornamentally. They were generally walls substantially coped, and furnished with handsome gates and piers. The rows of avenues and small clumps, or platoons intended to be finally thrown open, were enclosed by the most convenient temporary fence.”

- Sayers, Edward, 1838, The American Flower Garden Companion (p. 129) [43]

- “The trellises, arbors, walls, fences, and so on, should be covered with vines and creepers, so that the whole may have a corresponding appearance.”

- Loudon, Jane, 1845, Gardening for Ladies (pp. 410–11) [44]

- “WALLS for gardens are either used as boundary fences, and at the same time for the purpose of training plants on, or they are erected in gardens for the latter purpose only. They may be formed of different materials, according to those that are most abundant in any given locality; but the best of all walls for garden purposes are those which are built of brick. . . . In no case, however, ought garden walls, or indeed division or fence walls of any kind which have not a load to support perpendicularly, or a pressure to resist on one side, to be built with piers. . . . Walls of nine inches in thickness, and even four-inch walls, if built in a winding or zigzag direction, may be carried to a considerable height without either having piers or being built hollow; and such walls answer perfectly for the interior of gardens.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (pp. 221, 620–21) [45]

- “FENCES are employed to mark the boundary of property, to exclude trespassers, either human or quadrupedal, and to afford shelter. They are either live fences, and are then known as hedges, or dead, and are then either banks, ditches, palings, or walls; or they are a union of those two, to which titles the reader is referred. . . .

- “WALLS are usually built in panels, from fifteen to thirty feet in length, one brick thick, with pillars for the sake of adding to their strength, at these specified distances; the foundation a brick and a half thick. . . .

- “It is a practice sanctioned by economy, to build the wall half brick thick, on a nine inch foundation, and to compensate for its want of strength, a waved form is given. Both the smallness of its substance and its form, are found, however, to be inimical to the ripening of fruit.

- “In every instance a wall should never be lower than eight feet. The thickness usually varies with the height of the wall, being nine inches, if it is not higher than eight feet; thirteen and a half inches, if above eight and under fourteen feet; and eighteen inches, from fourteen up to twenty feet.

- “Fruit trees will succeed quite as well against a stone wall as against a brick one, although the former is neither so neat in appearance, nor can the trees be trained in such a regular form upon it as upon the latter. The last disadvantage may be in a great measure remedied by having a wooden or wire trellis affixed to it.—Gard. Chron.

- “If it be desirable that the roots of the trees should benefit by the pasturage outside the wall, it is very common to build it upon an arched foundation.

- “Colour has very considerable influence over a body’s power of absorbing heat. . . . The lightest coloured rays are the most heating, therefore light colored walls, but especially white, are the worst for fruit trees. The thermometer against a wall rendered black by coal tar, rises 5° higher in the sunshine, than the same instrument suspended against a red brick structure of the same thickness; nor will it cool lower at night, though its radiating power is increased by the increased darkness of its colour, if a proper screen be then employed.— Johnson’s Princ. of Gard.

- “Inclined or Sloping Walls have been recommended, but have always failed in practice. It is quite true that they receive the sun’s rays at a favourable angle, but they retain wet, and become so much colder by radiation at night than perpendicular walls, that they are found to be unfavourable to the ripening of fruit.”

- Downing, A. J., 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (pp. 343–44) [46]

- “An old stone wall covered with creepers and climbing plants, may become a picturesque barrier a thousand times superior to such a fence.”

Images

Inscribed

Michael van der Gucht, Illustration for chapter entitled: "Of different Terrasses and Stairs, with their most exact Proportions," in A.-J. Dézallier d'Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening(1712), pl. opp. p. 117.

Thomas Jefferson, Plan of an orchard at Monticello, c. 1778.

- 0555.jpg

Anonymous, Plat of 117 Broad Street, Charleston, 1797.

George Washington, Drawing and Notes for a Ha-Ha Wall at Mount Vernon, October 1798, 1798.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, General Plan of a Marine Asylum and Hospital proposed to be built at Washington, 1812.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Plan of the west end of the public appropriation in the city of Washington, called the Mall, as proposed to be arranged for the site of the university, 1816.

J. C. Loudon, "The flued wall, or hot-wall," in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1826), p. 304, figs. 236 and 237.

J. C. Loudon, "The wavy or serpentine wall" and "the angular wall," in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1826), p. 307, figs. 241 and 242.

J. C. Loudon, "Cross walls," in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1826), p. 471, fig. 427.

J. C. Loudon, "The mud or earth-wall," in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1826), p. 306, fig. 239.

J. C. Loudon, "The nurseryman's, or self-supported four-inch wall" and "The piered wall," in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1826), p. 308, figs. 245 and 246.

J. C. Loudon, "The cellular wall," in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1826), p. 305, fig. 238.

J. C. Loudon, "The cellular wall," in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1834), p. 577, figs. 562a and b.

J. C. Loudon, “The zig-zag wall” and “The square fret wall,” in An Encyclopædia of gardening (1834), pp. 578 and 579, figs. 568 and 569.

Frances Palmer, "Ground Plot," in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), vol. 2, pl. 29.

Associated

Robert Mills, Alternative plan for the grounds of the National Institution, 1841.

Anonymous, "Plan of a Suburban Garden," in A. J. Downing, ed., The Horticulturist 3, no. 8 (February 1849): pl. opp. p. 353.

Attributed

John or William Bartram, A Draught of John Bartram's House and Garden as it appears from the River, 1758.

Charles Willson Peale, William Paca, 1772.

Lewis Miller, "The Light Horseman," 1799.

William Russell Birch, "Pennsylvania Hospital, in Pine Street Philadelphia," 1800.

William Russell Birch, Sweet Briar, c. 1808, in Emily T. Cooperman and Lea Carson Sherk, William Birch: Picturing the American Scene (2011), p. 201, fig. 116.

Anne-Marguerite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny Hyde de Neuville, Le coin de F. Street Washington vis-à-vis nôtre maison été de 1817, 1817.

Anne-Marguerite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny Hyde de Neuville, Washington City, 1821.

Anthony St. John Baker, "View of the White House," 1826, in Mémoires d’un voyageur qui se repose (1850).

Anthony St. John Baker (artist), B. King (lithograper), Riversdale, near Bladensburg, 1827.

Henry Cheever Pratt, The House of Gardiner Greene, c. 1834.

Anonymous, "Residence of Gov. Morehead, North Carolina," in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), p. 387, fig. 46.

Notes

- ↑ William Forsyth, A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees (Philadelphia: J. Morgan, 1802), 150, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For an analysis of the function and significance of walls and gates in Latin American vernacular architecture, and particularly in the enclosure of the patio garden, see William J. Siembieda, “Walls and Gates: A Latin Perspective,” Landscape Journal 15 (Fall 1996): 113–32, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Wilbur Zelinsky cites in 1871 that the Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture included data for fence types in New England. The frequency of stone fences ranged from 32 percent in Vermont to a high of 79 percent in Rhode Island. See Ervin H. Zube and Margaret J. Zube, eds., Changing Rural Landscapes (1951; repr., Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1977), 59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Philip Dole, “The Picket Fence at Home,” in Between Fences, ed. Gregory K. Dreicer (Washington, DC: National Building Museum, 1996), 28–30, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alice B. Lockwood, ed., Gardens of Colony and State: Gardens and Gardeners of the American Colonies and of the Republic before 1840, 2 vols (New York: Charles Scribner’s for the Garden Club of America, 1931), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gerald W. Johnson, Mount Vernon: The Story of a Shrine (New York: Random House, 1953), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Darlington, Memorials of John Bartram and Humphry Marshall: With Notices of Their Botanical Contemporaries (Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ François Jean, Marquis de Chastellux, Travels in North America in the Years 1780, 1781, and 1782, 2 vols (London: G. G. J. and J. Robinson, 1787), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Lee Shippen, Westover Described in 1783: A Letter and Drawing Sent by Thomas Lee Shippen, Student of Law in Williamsburg, to His Parents in Philadelphia (Richmond, Va.: William Byrd Press, 1952), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jedidiah Morse, The American Geography; Or, A View of the Present Situation of the United States of America (Elizabeth Town, N.J.: Shepard Kollock, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bentley, The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts (Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith, 1962), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels in New England and New York, 4 vols (New Haven, Conn.: Timothy Dwight, 1821), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Arthur Hammond, ""Where the Arts and the Virtues Unite”: Country Life Near Boston, 1637-1864" (unpublished Ph.D. diss., Boston University, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John C. Ogden, An Excursion into Bethlehem & Nazareth, in Pennsylvania, in the Year 1799 (Philadelphia: Charles Cist, 1800), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Scott, A Geographical Description of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Printed by R. Cochran, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Drayton, "The Diary of Charles Drayton I, 1806," 1806, Drayton Hall: A National Historic Trust Site, http://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:27554, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Stebbins, The Journal of William Stebbins, ed. by Pierce W. Gaines (Hartford, Conn.: Acorn Club, 1968), view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, A Statement of Facts Relative to the Establishment and Progress of the Elgin Botanic Garden (New York: C. S. Van Winkle, 1811), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al, eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family: Charles Willson Peale: Artist in Revolutionary America, 1735-1791. Vol. 1; Charles Willson Peale, Artist as Museum Keeper, 1791-1810. Vol 2, Pts. 1-2; The Belfield Farm Years, 1810-1820. Vol. 3; The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale. Vol. 5. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1983–2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Cullen Bryant, The Letters of William Cullen Bryant, ed. by William Cullen II Bryant and Thomas G. Voss (New York: Fordham University Press, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Breck, "Gardens, Hot-Houses, &c., in the Vicinity of Boston", The Horticultural Register and Gardener’s Magazine, 2 (1836), 41–47, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Story Kirkbride, Reports of the Pennsylvania Hospital for The Insane: For the Years 1846-7-8-9 and 50 (Philadelphia: Published by order of the Board of Managers, 1851), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, ed. by Gaillard Hunt (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1906), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pamela Scott, ed., The Papers of Robert Mills (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1990), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles B. Trego, A Geography of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Edward C. Biddle, 1843), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, "Description of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, with Remarks", The American Journal of Insanity, 4 (1848), 347–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed., corr. and improved (London: Longman et al., 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William H. Ranlett, The Architect, 2 vols (New York: Da Capo, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (London: Humfrey Lownes and Robert Young, 1629), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . ., 5th edn, 2 vols (London: D. Midwinter et al, 1741), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Philip Miller, The Gardeners Dictionary (New York: Verlag Von J. Cramer, 1969), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Isaac Ware, A Complete Body of Architecture (London: T. Osborne and J. Shipton, 1756), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Philip Miller, The Gardeners Dictionary: Containing the Methods of Cultivation and Improving the Kitchen, Fruit, and Flower Garden. As Also, the Physick Garden, Wilderness, Conservatory, and Vineyard... Interspers’d with the History of the Plants, the Characters of Each Genus and the Names of All the Particular Species, in Latin and English; and an Explanation of All the Terms Used in Botany and Gardening, Etc., 7th edn (London: Philip Miller, 1759), view on zotero.

- ↑ Thomas A. Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews...., 5th edn (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Deane, The New-England Farmer, or Georgical Dictionary (Worcester, Mass.: Isaiah Thomas, 1790), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Forsyth, A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees (Philadelphia: J. Morgan, 1802), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M’Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done... for Every Month of the Year.... (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Gregory, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, First American, from the second London edition, considerably improved and augmented, 3 vols (Philadelphia: Isaac Peirce, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Gardiner and David Hepburn, The American Gardener, Expanded ed. of 1804 original (Georgetown, D.C.: Joseph Milligan, 1818), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Bridgeman, The Young Gardener’s Assistant, 3rd edn (New York: Geo. Robertson, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, New ed., considerably improved and enlarged (London: Longman et al, 1834), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Sayers, The American Flower Garden Companion, Adapted to the Northern States (Boston: Joseph Breck and Company, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden, ed. by A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. by David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th edn (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.