Difference between revisions of "John Bartram"

M-westerby (talk | contribs) |

M-westerby (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

|Other resources={{ExternalLink | |Other resources={{ExternalLink | ||

|External link URL=https://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n50018648.html | |External link URL=https://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n50018648.html | ||

| − | |External link text= | + | |External link text=Library of Congress Authority File |

}} | }} | ||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 20:00, September 8, 2021

Overview

Birth Date: March 23, 1699

Death Date: September 22, 1777

Used Keywords: Alley, Arbor, Bed, Border, Botanic garden, Canal, Fence, Gate/Gateway, Greenhouse, Hedge, Parterre, Plantation, Thicket, Walk, Wall

Other resources: Library of Congress Authority File;

John Bartram (March 23, 1699–September 22, 1777), an American-born botanist, horticulturalist, and explorer, established in the early 1730s the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery near Philadelphia. He made significant contributions to the collection, study, and international dissemination of North American flora and fauna, and was a pioneer in the importation and cultivation of non-native plants. His son William Bartram (1739–1823) would become an important naturalist, artist, and author, known for his botanical illustrations and his travelogue of 1791, Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws.

History

The son of a Quaker farmer in rural Pennsylvania, John Bartram possessed from an early age a “great inclination to botany & natural history,” which he pursued through exploration and independent study.[1] In his late twenties, Bartram purchased farm land on the banks of the lower Schuylkill River a few miles from Philadelphia, reserving a half dozen acres for gardens.[2] While exploring the surrounding countryside, he foraged for local plants—both for his garden, and for his friends Benjamin Franklin and Joseph Breintnall (d. 1746), who in the early 1730s were creating a comprehensive set of nature prints documenting indigenous leaf and grass specimens.[3] In 1733 Breintnall sent a set of the prints to Peter Collinson, an enterprising merchant and Fellow of the Royal Society in London.[4] Breintnall also informed Collinson that Bartram would be “a very proper person” to furnish him with actual seeds and plants from North America. “Being a native of Pensilvania with a numerous Family,” Breintnall observed, “The profits ariseing from Gathering Seeds would enable him to support it.”[5] With that, Bartram and Collinson embarked on a thirty-five-year exchange of botanical materials that forever altered the vegetation of Britain and America.[6]

Collinson coached Bartram in practical techniques for collecting and preserving plants, insects, and animals, while also fostering his knowledge of botany. Early in 1735 he requested that Bartram ship duplicate specimens so that he could “gett them named by our most knowing Botanists and return them again—which will improve thee more than Books.”[7] In May 1737 Collinson returned 208 specimens to Bartram, with identifications made by Johann Jacob Dillenius (1684–1747), curator of the Oxford University Botanic Garden.[8] Working through Collinson’s connections, Bartram began supplying plants, seeds, roots, and tubers to eminent members of the European scientific community, including Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), president of the Royal Society and patron of the Chelsea Physic Garden in London; Philip Miller, director of the Chelsea Physic Garden; and Carl Linnaeus, professor of medicine and botany at Uppsala University in Sweden.[9] He also filled requests from wealthy estate owners keen to ornament their gardens with fashionable American trees and shrubs. Among Bartram’s most generous clients was Collinson’s great friend Robert James Petre, 8th Baron Petre (1713–1742), who preserved some of Bartram’s specimens in an herbarium.[10] As demand grew, Bartram began to standardize his practice, assembling boxes containing 100 specimens, mostly of trees and shrubs, that were distributed to British subscribers recruited by Collinson.[11]

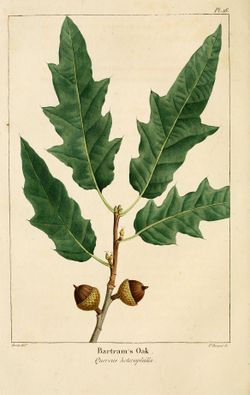

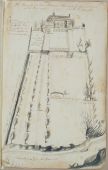

The seeds and plants Bartram received in exchange for those he supplied contributed to his creation of botanic gardens of encyclopedic range. A drawing made by Bartram or his son William in 1758 (evidently for Peter Collinson) provides insights into the layout of the gardens, though scant information about their contents. The drawing shows a fenced enclosure containing a “Common Flower Garden” and a “new flower garden” adjacent to Bartram’s freestanding “Study” [Fig. 1]. The drawing also shows a small kitchen garden at the back of the main house, connected by a flight of steps to a larger kitchen garden. A pond near the center of the lower kitchen garden conveyed water to the spring or milk house at the far edge of the property. At the opposite side, two tree-lined walks led 150 yards down a moderate slope to the river’s edge. Several of the plants cultivated in the garden were new discoveries made by Bartram. These included the Bartram Oak (Quercus x heterophylla), a rare hybrid of red and willow oak that he identified at William Hamilton's neighboring estate, The Woodlands [Fig. 2], and Franklinia alatamaha, a nearly extinct flowering tree that Bartram and his son William first observed on the Alatamaha River in Georgia in 1765.[12]

Bartram expanded his knowledge of botany by carrying out plant dissections and experiments with the aid of magnifying lenses he devised in consultation with his Philadelphia neighbor James Logan, an authority on optics.[13] Tinkering with artificial pollination in 1739 at the request of “some ingenious botanists in Leyden,” Bartram obtained “curious mixed colours in flowers never known before,” which he considered “A gate into A very bare field of experimental knowledge which if Judiciously improved may be A Considerable Addition to ye beauty of ye florists gardens.”[14] Bartram yearned to create in Philadelphia an association of “ingenious & Curious men” to share knowledge of the “natural secrets arts & scyences.”[15] At his prompting, Benjamin Franklin circulated a proposal that led to the establishment in 1743 of the American Philosophical Society, loosely modeled on the Royal Society in London.[16] Bartram’s correspondents often sent him books, enabling him to further his education while building a valuable natural history reference library. For his services to Dillenius, he received the first volume of Phillip Miller's Gardener’s Dictionary in 1737, with the supplement arriving two years later, the gift of Lord Petre.[17] Bartram entered into a more complicated arrangement with the English botanist Mark Catesby, whose magisterial two-volume Natural History contained several Bartram-supplied plants from Peter Collinson's garden. Beginning in 1740, Catesby sent annual installments of his book to Bartram in exchange for American plants—several of which then appeared in the final supplement to the Natural History.[18] In 1745 Collinson’s campaigning on Bartram’s behalf resulted in the naming of a genera of mosses Bartramia by an international group of naturalists led by Linnaeus.[19]

Bartram traveled up and down the East Coast virtually every year from 1735 through 1766, gathering unusual plants and touring gardens from New England to the Floridas.[20] Attention to the natural habitats of plants shaped Bartram’s understanding of botany and his approach to the botanic garden and nursery he was developing at his Schuylkill River farm.[21] Equipped by Collinson with a detailed itinerary, pocket magnifying glass, and letters of introduction, he trekked through Maryland and Virginia in the autumn of 1738, where he was disappointed to find the gardens “poorly furnished with Curiosities.” Even those of the wealthy planter William Byrd II and the botanist John Clayton lacked the variety of Philadelphia’s gardens, enriched by importations from England, France, Holland, and Germany.[22] Bartram frequently visited New Jersey and New York, and while exploring the Catskill mountains in 1842, he made the first of several visits to the Irish-born physician and botanist Cadwallader Colden and his daughter Jane, with whom he carried on a lengthy correspondence.[23] In the spring of 1754, they introduced him to Dr. Alexander Garden of Charleston, who rejoined Bartram in Philadelphia a few months later, spending several days exploring the surrounding countryside in his company.[24] Bartram returned Garden’s visit in 1760 on his first trip to the Carolinas.[25] Dr. Samuel Green, whom Bartram met in Wilmington, disappointed him by failing to send promised specimens,[26] but he was delighted by the acquaintances he made in Charleston. Elizabeth and Thomas Lamboll became reliable correspondents and suppliers of tropical specimens,[27] and a brief encounter with the Charleston horticulturalist Martha Daniell Logan, author of the Gardeners Kalender, initiated a mutually beneficial exchange of seeds, roots, and bulbs.[28] Bartram reported to his cousin Humphry Marshall in September 1760, “My garden now makes A glorious appearance with ye virginia & Carolina flowers.”[29]

In the 1750s and 60s Bartram’s commercial business faced competition from James Alexander, Thomas Penn’s gardener at neighboring Springettsbury. Bartram and Collinson kept close tabs on the rare and unusual plants—“fine Ornaments in a Flower Garden”—that Alexander sent to England.[30] Collinson sought to boost Bartram’s business by repeatedly publishing his seed catalogue in Gentleman’s Magazine in London during the 1750s, touting it as “the largest Collection that has ever before been imported into this Kingdom.”[31] In addition to supplying North American seeds and live plants to correspondents in England, France, Denmark, Germany, Sweden, and Scotland, Bartram was also meeting a burgeoning market in the American colonies for exotic specimens from around the globe.[32] By the 1760s he was wearying of the seemingly insatiable demand for novel curiosities. He complained to Collinson in 1761: “Do they think I can make new ones[?] I have sent them seeds of almost every tree & shrub from Nova scotia to Carolina very few is wanting & from ye sea across ye continent to ye lakes & if I die A martyr to Botany Gods will be done.”[33] Nevertheless, he continued to take on important new clients. In 1764 Bartram began collecting seeds for a new botanic garden in Edinburgh at the request of Dr. John Hope (1725–1786), King’s Botanist for Scotland and professor of botany at the University of Edinburgh (view text)—a venture that resulted in Bartram’s receiving a gold medal for meritorious service in 1772.[34]

Many seeds and specimens gathered by Bartram found their way to the royal gardens at Kew, and in September 1764 Bartram assembled a box of “new discovered specimens” of plants for George III.[35] The king retained Bartram’s services the following April at an annual stipend of £50, with the expectation that he would explore Britain’s new Florida provinces and report back to London—an arrangement that owed much to the lobbying efforts of Collinson and Franklin.[36] The king’s offer trumped that of Lord Adam Gordon, who simultaneously offered to fund Bartram on expeditions to Quebec and Pensacola, where he hoped to invest in land.[37] Bartram fulfilled his royal commission in February 1766, having spent eight weeks exploring the St. John’s River in East Florida with his son William. Bartram’s report was published in the second edition of Dr. William Stork’s A Description of East-Florida, with a Journal Kept by John Bartram of Philadelphia, Botanist to His Majesty for the Floridas; upon A Journey from St. Augustine up the River to St. John’s as far as the Lakes (1766). Bartram’s East Florida expedition was his last, and he retired in 1771, leaving his nursery business to be carried on by his sons John and William Bartram.

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Bartram, John, May 1738, letter to Peter Collinson, describing sloe trees near Philadelphia (1992: 89)[38]

- “The first I observed sloe trees was at a plantation whose owner came two years into this country before A house was builded in Philadelphia[.] I saw another tree near Philadelphia as thick as my thigh & last year I showed James Logan English thorns, Bullises & sloes growing in A hedge which he rides close by from his house to town which I believe hath been planted 20 years.”

- Bartram, John, July 18, 1739, letter to Peter Collinson, describing Westover (1992: 121)[38]

- “Col Byrd is very prodigal in Gates roads walks hedges & seeders [cedars] trimed finely & A little green house with 2 or 3 [orange] trees . . .”

- Bartram, John, June 11, 1743, letter to Peter Collinson, describing the garden of Dr. Christopher Witt (1675–1765) in Germantown, PA (1992: 215–16)[38]

- “I have lately been to visit our friend Doctor wit [Witt] where I spent 4 of 5 very agreeable sometimes in his garden where I viewed every kind of plant I believe that grew therin. . . . I observed particularly the Doctors famous Lychnis which thee hath dignified so highly, is I think unworthy of that Character our swamps & low grounds is full of them I had so contemptible an opinion of it as not to think it worthy sending nor afford it room in my garden.”

- Kalm, Peter [Pehr], September 25, 1748, Travels into North America (1770, 1:112–113)[39]

- “Mr. John Bartram is an Englishman, who lives in the country about four miles from Philadelphia. He has acquired a great knowledge of natural philosophy and history, and seems to be born with a peculiar genius for these sciences. . . . He has in several successive years made frequent excursions into different distant parts of North America, with an intention of gathering all sorts of plants which are scarce and little known. Those which he found he has planted in his own botanical garden, and likewise sent over their seeds or fresh roots to England. We owe to him the knowledge of many scarce plants, which he first found, and which were never known before. Yet with all these great qualities, he is to be blamed for his negligence, for he did not care to write down his numerous observations.”

- Garden, Alexander, November 4, 1754, letter to Cadwallader Colden, describing John Bartram (quoted in Colden 1921: 4:471–72)[40]

- “I have met wt very Little new in the Botanic way unless Your acquaintance Bartram, who is what he is & whose acquaintance alone makes amends for other disappointments in that way . . . . One Day he Dragged me out of town & Entertain’d me so agreably with some Elevated Botanicall thoughts, on oaks, Firns, Rocks & c that I forgot I was hungry till we Landed in his house about four Miles from Town . . . .

- “His garden is a perfect portraiture of himself, here you meet wt a row of rare plants almost covered over wt weeds, here with a Beautiful Shrub, even Luxuriant Amongst Briars, and in another corner an Elegant & Lofty tree lost in common thicket—on our way from town to his house he carried me to severall rocks & Dens where he shewed me some of his rare plants, which he had brought from the Mountains &c. In a word he disdains to have a garden less than Pensylvania [sic] & Every den is an Arbour, Every run of water, a Canal, & every small level Spot a Parterre, where he nurses up some of his Idol Flowers & cultivates his darling productions. He had many plants whose names he did not know, most or all of which I had seen & knew them—On the other hand he had several I had not seen & some I never heard of.”

- Bartram, John, June 24, 1760, letter to Peter Collinson, describing his plans for the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, vicinity of Philadelphia, PA (1992: 486)[38]

- “Dear friend, I am going to build a greenhouse. Stone is got; and hope as soon as harvest is over to begin to build it, to put some pretty flowering winter shrubs, and plants for winter’s diversion; not to be crowded with orange trees, or those natural to the Torrid Zone, but such as will do, being protected from frost.”

- Collinson, Peter, September 15, 1760, letter to John Bartram, commenting on plans to build a greenhouse (1849: 224–25)[41]

- “I am pleased thou will build a green-house. I will send thee seeds of Geraniums to furnish it. They have a charming variety, and make a pretty show in a green-house; but contrive and make a stove in it, to give heat in severe weather.”

- Bartram, John, November 8, 1761, letter to Peter Collinson, contrasting American wilderness with English gardens (1992: 538)[38]

- “My correspondents near London writes to me as freely for ye Carolina plants as if they thought I could get them as easy as they do ye plants in ye European gardens that is to walk at their leisure along ye alleys & dig what they please out of ye beds, without ye danger of life and limb.”

- Bartram, John, December 3, 1762, letter to Peter Collinson, describing Charleston, SC (1992: 579)[38]

- “I can’t find, in our country, that south walls are much protection against our cold, for if we cover so close as to keep out the frost, they are suffocated.”

- Hope, John, November 4, 1763, letter from Edinburgh to John Bartram (1849: 432–33)[41]

- “The great reputation which you have just acquired, by many faithful and accurate observations, and that most extraordinary thirst of knowledge which has distinguished you, makes me extremely desirous of your correspondence.

- “If you will be so kind as send me a few seeds of your new discovered plants, I shall on my part make a return of whatever is in my power, that I shall judge agreeable to you.

- “It will be agreeable to you to hear that Mr. Samuel Bard, son of your friend Mr. Bard, of New York, is making most wonderful progress in Botany, and has made a beautiful collection of near four hundred Scots plants; by which he undoubtedly will gain the annual premium.” back up to History

- Bartram, John, October 4, 1764, letter to Dr. John Hope (1849: 433–34)[41]

- “I have received your proposals by the hands of our dear friend Benjamin [Franklin]; and since, by a letter from the worthy, humane Dr. [John] Bard, or New York, in which he inserts a paragraph of a letter from his son (whose person and activity I am not a stranger to), wherein he writes to the same effect as thee wrote to Benjamin Franklin, signifying that you had laid a new botanic garden to be stored with exotics; that you were forming a laudable and very necessary plan of storing your bare country with variety of forest trees; that many gentlemen of rank and fortune had countenanced this scheme with an annual subscription, to enable a botanist to make your desired collections; and that my answer was desired, whether I would undertake to supply your demands, which I consent to do, if your generosity is equal to them; for the charges of collecting rare vegetables are in proportion to the distance from home, and hazards and dangers in collecting them. . . .

- “I have now sent, as a present, for thy curious amusement, one hundred specimens, some rare, with my remarks upon them, and to your new garden a parcel of curious seeds, near one hundred and fifty different species; and our friend, Benjamin Franklin, engaged me to send you a box of forest trees and shrubs, in which I am going to pack above one hundred different kinds, and send them in the next ship for London.”

- Mr. Iw—n Al—z, c. 1770, describing John Bartram and the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (quoted in Letters from an American Farmer 1783: 248, 254)[42]

- “Let us . . . pay a visit to Mr. John Bertram [sic], the first botanist, in this new hemisphere. . . . It is to this simple man that America is indebted for several useful discoveries, and the knowledge of many new plants. . . .

- “Every disposition of the fields, fences, and trees, seemed to bear the marks of perfect order and regularity, which in rural affairs, always indicate a prosperous industry. . . .

- “From his study we went into the garden, which contained a great variety of curious plants and shrubs; some grew in a green-house, over the door of which were written these lines,

- “Slave to no sect, who takes no private road,

- “But looks through nature, up to nature’s God!"

- Thacher, James, 1828, describing history of Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (1828: 1:67)[43]

- “Mr. Bartram was the first native American who conceived and carried into effect the plan of a botanical garden for the reception and cultivation of indigenous as well as exotic plants, and of travelling for the purpose of accomplishing this plan. He purchased a situation on the banks of Schuylkill, and enriched it with every variety of the most curious and beautiful vegetables, collected in his excursions, which his sons have since continued to cultivate.”

- Darlington, William, 1849, describing Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, vicinity of Philadelphia, PA (1849: 18–19)[41]

- “He [John Bartram] was, perhaps, the first Anglo-American who conceived the idea of establishing a BOTANIC GARDEN for the reception and cultivation of the various vegetables, natives of the country, as well as exotics, and of travelling for the discovery and acquisition of them.

- “The BARTRAM BOTANIC GARDEN, (established in or about the year 1730,) is most eligibly and beautifully situated, on the right bank of the river Schuylkill, a short distance below the city of Philadelphia. Being the oldest establishment of the kind in this western world, and exceedingly interesting, from its history and associations,—one might almost hope, even in this utilitarian age, that, if no motive more commendable could avail, a feeling of state or city pride, would be sufficient to ensure its preservation, in its original character, and for the sake of its original objects. But, alas! there seems to be too much reason to apprehend that it will scarcely survive the immediate family of its noble-hearted founder,—and that even the present generation may live to see the accumulated treasures of a century laid waste—with all the once gay parterres and lovely borders converted into lumberyards and coal-landings.”

Images

John or William Bartram, "A Draught of John Bartram’s House and Garden as it appears from the River", 1758.

Other Resources

Library of Congress Authority File

The Cultural Landscape Foundation

Notes

- ↑ Quotation from John Bartram to Alexander Catcott, May 26, 1742, in John Bartram, The Correspondence of John Bartram 1734–1777, ed. Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1992), 193, view on Zotero; see also Joel T. Fry, John Bartram’s House and Garden (Bartram’s Garden), Historic American Landscape Survey, HALS No. PA-1, 2004, 19–22, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fry 2004, 27–28, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alan W. Armstrong, “John Bartram and Peter Collinson: A Correspondence of Science and Friendship,” in America’s Curious Botanist: A Tercentennial Reappraisal of John Bartram, 1699–1777, ed. Nancy Everill Hoffmann and John C. Van Horne (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2004), 28, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. A. Leo Lemay, The Life of Benjamin Franklin, 3 vols. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 2 (Printer and Publisher, 1730–1747), 463, view on Zotero; “Extracts from the Gazette, 1733,” The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, 47 vols., ed. Leonard W. Labaree (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959), 1:349n6, view on Zotero; Edwin Wolf II and Marie Elena Korey, eds., Quarter of a Millennium: The Library Company of Philadelphia, 1731–1981: A Selection of Books, Manuscripts, Maps, Prints, Drawings, and Paintings (Philadelphia: The Library Company of Philadelphia, 1981), 17, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter Collinson, “Forget Not Mee & My Garden”: Selected Letters 1725–1768 of Peter Collinson, F.R.S., ed. Alan W. Armstrong (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2002), xxvi, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For Bartram’s concern about the environmental impact of invasive European plants introduced to America, see Bartram 1992, 451–54, view on Zotero; Stephanie Volmer, “Planting a New World: Letters and Languages of Transatlantic Botanical Exchange, 1733–1777” (PhD diss., Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 2008), 54–57, view on Zotero. For an overview of Bartram’s relationship with Collinson, see Armstrong 2004, 23–42, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter Collinson to John Bartram, January 24, 1735, in Bartram 1992, 4, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 48–57, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, view on Zotero; Alfred E. Schuyler, “On the Discovery of Helonias Bullata L. (Swamp-Pink) and the Source of the Specimens in the Linnaean Herbarium,” Pennsylvania Legacies 4 (November 2004): 10–13, view on Zotero; Hazel Le Rougetel, “Philip Miller/John Bartram Botanical Exchange,” Garden History 14 (Spring 1986): 32–39, view on Zotero; Sarah P. Stetson, “The Traffic in Seeds and Plants from England’s Colonies in North America,” Agricultural History 23 (January 1949): 50–55, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Edmondson, “John Bartram’s Legacy in Eighteenth-Century Botanical Art: The Knowsley Ehrets,” in Hoffmann and Van Horne 2004, 143–45, 148–50, view on Zotero; Joel T. Fry, “John Bartram and His Garden: Would John Bartram Recognize His Garden Today?”, in Hoffmann and Van Horne 2004, 249, view on Zotero; Armstrong 2004, 24, 27, 29, 30, 38, view on Zotero; Douglas Chambers, The Planters of the English Landscape Garden: Botany, Trees, and the Georgics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 110–19, view on Zotero; Mark Laird, The Flowering of the Landscape Garden: English Pleasure Grounds, 1720–1800 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), 63–78, view on Zotero; Alfred E. Schuyler and Ann Newbold, “Vascular Plants in Lord Petre’s Herbarium Collected by John Bartram,” Bartonia 53 (1987): 41–43, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For various estimates of the number of subscribers, see Fry 2004, 24–25, view on Zotero; Whitfield J. Bell Jr., Patriot-Improvers: Biographical Sketches of Members of the American Philosophical Society, 3 vols. (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1997), 1:50, view on Zotero; Volmer 2008, 39, view on Zotero; Armstrong 2004, 30, 38, view on Zotero; Laird 1999, 80, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter De Tredici, “Against All Odds: Growing Franklinia in Boston,” Arnoldia 63 (2005): 3, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 32, 71–72, view on Zotero; for microscopes and an instructional pamphlet that Collinson sent to Bartram in the 1740s and 1750s, see pp. 241, 375, and 441.

- ↑ John Bartram to William Byrd II, n.d. (c. summer, 1739), in Bartram 1992, 120, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Bartram to Peter Collinson, n.d. (c. 1737), in Bartram 1992, 66, view on Zotero; see also p. 93.

- ↑ Benjamin Franklin, The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, ed. Leonard W. Labaree, 47 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961), 2:378–83, view on Zotero; Raymond Phineas Stearns, Science in the British Colonies of America (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1970), 670–74, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 47–48, 65, 224, view on Zotero; see also pages 14, 122, 181, 184, 187, 194, 196, 202, 248–249.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 132–33, view on Zotero; David R. Brigham, “Mark Catesby and the Patronage of Natural History in the First Half of the 18th Century,” in Empire’s Nature: Mark Catesby’s New World Vision, ed. Amy R. W. Meyers and Margaret Beck Pritchard (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press (published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1998), 121–22, view on Zotero; James L. Reveal, “Identification of the Plant and Associated Animal Images in Catesby’s 'Natural History,' with Nomenclatural Notes and Comments,” Rhodora 111 (2009): 304, 338, 339, 358, 362, 363, 372, view on Zotero; George Frederick Frick and Raymond Phineas Stearns, Mark Catesby: The Colonial Audubon (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1970), 90–91, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 145–46, 235, 241, 280, 282, 435, view on Zotero.

- ↑ The exception to this rule was a four-year hiatus from 1746 to 1749. For timelines and annotated maps documenting Bartram’s travels, see Hoffmann and Van Horne 2004, xviii–xxvi, view on Zotero. See also Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley, eds., The Life and Travels of John Bartram from Lake Ontario to the River St. John (Tallahassee: University Presses of Florida, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “Art and Science in the Design of Botanic Gardens, 1730–1830,” in Garden History: Issues and Approaches, ed. John Dixon Hunt (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1992), 282, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Bartram to Peter Collinson, July 18, 1739, in Bartram 1992, 121; see also pp. 84–85, 114; for Collinson’s gift of a magnifying glass in 1737, see 59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 202; see also pages 150–51, 165, 181, 218–19, 246, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hoffmann and Van Horne 2004, xx,view on Zotero; Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley, Dr. Alexander Garden of Charles Town (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1969), 42–46, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 498, view on Zotero; Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 151–154, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 513, 532, 538–39, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 504, 511, 549–50, 575, 614, 620, 634–35, 637–38, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Bartram to Peter Collinson, May 22, 1761, in Bartram 1992, 517, view on Zotero; Martha Daniell Logan, “Letters of Martha Logan to John Bartram, 1760–1763,” ed. Mary Barbot Prior, South Carolina Historical Magazine 59 (1958): 38–46, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Bartram to Humphry Marshall, September 17, 1760, in Bartram 1992, 495, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Quotation from Peter Collinson to John Bartram, Bartram 1992, 343; see also pages 302, 343, 378, 393, 407, 410, 430, 458, 513, 521, 530, 534, 572, 583, 613, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Armstrong 2004, 25, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 645, view on Zotero; Fry 2004, 37, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Bartram to Peter Collinson, August 14, 1761, in Bartram 1992, 534, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 640, 643–44, 737–38, view on Zotero; John H. Harvey, “A Scottish Botanist in London in 1766,” Garden History 9 (1981): 40–75, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 638–39, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Franklin, The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, ed. by Leonard W. Labaree, 47 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1967), 12: 61–62, view on Zotero; Bartram 1992, 644, 682, 701, 708; for confusion concerning Bartram’s right to the title of “King’s Botanist,” see also pages 646, 654, 679–680, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 649, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 38.5 Bartram 1992, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter [Pehr] Kalm, Travels into North America: Containing Its Natural History, and a Circumstantial Account of Its Plantations and Agriculture in General, with the Civil, Ecclesiastical and Commercial State of the Country, the Manners of the Inhabitants, and Several Curious and Important Remarks on Various Subjects, trans. John Reinhold Forster, 3 vols. (London: John Reinhold Forster, 1770), 1, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cadwallader Colden, The Letters and Papers of Cadwallader Colden, vol. 4 (1748–1754), Collections of the New-York Historical Society (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1920), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 William Darlington, Memorials of John Bartram and Humphry Marshall: With Notices of Their Botanical Contemporaries (Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ “A Russian Gentleman, Describing the Visit He Paid at My Request To Mr. John Bertram, The Celebrated Pennsylvanian Botanist,” quoted in J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur, Letters from an American Farmer: Describing Certain Provincial Situations, Manners, and Customs Not Generally Known (London: Thomas Davies and Lockyer Davis, 1783), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Thacher, American Medical Biography: Or, Memoirs of Eminent Physicians Who Have Flourished in America, 2 vols. (Boston: Richardson & Lord and Cottons & Barnard, 1828), view on Zotero.