The Evidence of American Garden History

Interpreting American Gardens through Words and Images

Therese O’Malley

In 1813, Charles Willson Peale wrote a letter to his daughter Angelica in which he described the improvements he was making to his garden at Belfield, near Philadelphia [Fig. 1]: “I have made an Oblisk to terminate a Walk in the Garden. Read in Dictionary of Arts for description of them. I made it of rough boards & white washed it with lime & allum.”[1] The book that Peale relied upon was Gregory’s Dictionary of Art and Sciences, published in London in 1807.[2] This is a rare, straightforward example of an American’s reliance on imported literature and of the interpretation and execution of its designs. What makes this example rich for the garden historian is that Peale illustrated his obelisk in his letter next to the written description [Fig. 2]. He did this not once but a second time, in another letter to his daughter [Fig. 3]. In addition, Peale’s autobiography includes a description of the obelisk and its inscriptions. We also have correspondence between Peale and Thomas Jefferson about an obelisk that Jefferson was planning for his garden at Monticello.[3] This happy confluence of literary and visual references provides us with an unusually complete picture of a single garden element for the garden at Belfield. With this kind of evidence we may comfortably discuss the influence of European literature and garden features upon one early American garden.[4] The material, in fact, allows us to say why this feature was called an obelisk in this period in Philadelphia, a remarkable outcome considering that in most cases we are left with only fragmentary clues about the design, function, and meaning of historic gardens.

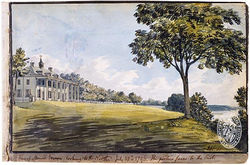

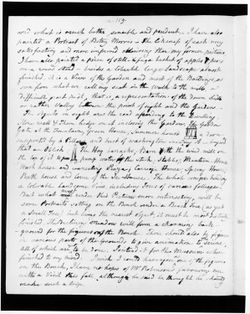

An evocative, if less complete, example is the testimony of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, who in 1743 wrote about Crowfield in South Carolina to a friend in London. She described a “spacious bason in the midst of a large green. . . as you enter the gate that leads to the house. . . a spacious walk a thousand feet long; on each side of which nearest the house is a grass plat ennamiled in a Serpenting manner with flowers. . . a thicket of young tall live oaks. . . a large square boleing green sunk a little below the level of the rest of the garden.”[5] Here we have a lively and specific description of a basin, a thicket, and a bowling green. No visual record, however, survives to corroborate it. What did the features itemized in this letter look like? The painting entitled South West Prospect of the Seat of Colonel George Boyd of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, by an unknown artist [Fig. 4], depicts a large central feature that may be a pool or basin. Is it like the basin mentioned by Eliza Pinckney?

The goal of this digital resource is to study the decisive or original meanings of words found in authoritative texts, such as treatises, and to compare them with depicted and actual examples in order to understand the extensions, variations, and derivative meanings that arise through use. We can extrapolate from these clues to gain a more complete understanding of individual landscape features and the appropriate vocabulary to describe them. As Raymond Williams notes in his book Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society, there exists a difficult relationship between words and concepts, words and objects, and, of particular concern here, words and images.[6] This website, History of Early American Landscape Design (HEALD), provides a history of early American gardens based on extensions, varieties, and transfers of original forms and meanings of garden words and objects.

In this search for organized meanings, this website focuses on two bodies of primary materials, one literary and one visual. The first category includes the treatises and garden literature we know to have circulated in North America, which provided models and instructions for garden making. Batty Langley, Philip Miller, and, later, John Claudius Loudon published three of the most important treatises in use in America.[7] Each provided extensive passages instructing gardeners in the planting, management, and aesthetics of the garden. The first American garden treatises did not appear until the turn of the 19th century.[8] These publications, however, reveal a well-developed theory of the ornamental landscape and the design of pleasure grounds.

In addition to published literature, and perhaps more telling of the reality of garden making, are the notices and descriptions of gardens in common usage, correspondence, and travel writing, as well as in inscriptions on drawings and prints. This material reveals the diversity of, as well as the similarities among, American gardens as they appeared throughout the period and across the country.

Parallel to written documents, a large corpus of images compiled from drawings, paintings, textiles, wallpaper, ceramics, insurance surveys, travel sketches, and prints depicts a rich variety of garden design. The great range inspires the question of the relationship between the realized garden and the idealized versions illustrated in contemporaneous literature and art. What is the relationship between the real and the ideal? As Donald Meinig has written, an ideal “can be at once a mold and mirror of the society that created it.”[9] W. J. T. Mitchell stated it in other terms: We can study not only the social construction of the visual field, but also the visual construction of the social field.[10] What is gardening, but that?

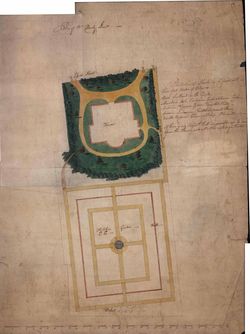

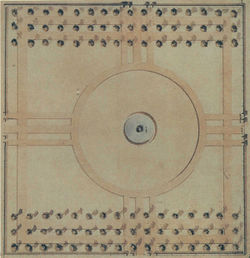

Some images reproduced on this website have only recently been discovered, have never been published, or are little known. For example, the plan for Tryon Palace gardens at New Bern, North Carolina, the governor’s palace, drafted either by the English architect John Hawks or cartographer Claude Joseph Sautier around 1783, was recently found in archives in Caracas, Venezuela [Fig. 5]. The architect’s inscription is useful for understanding the relationship between a representation and the actual garden: “It was agreed for the advantage of a prospect down the river, that the South front should be thrown more to the Eastward which leaves the gardens not quite so regular as appears in the sketch.”[11] The elaborate parterres and overall symmetry of the original scheme reflect what was often called the French or ancient style.[12]

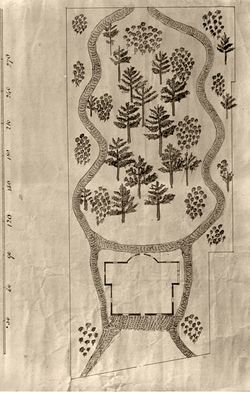

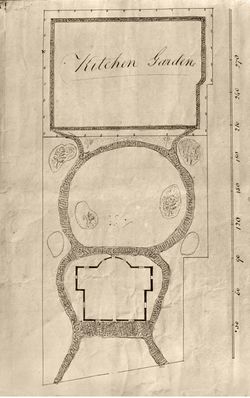

A little-known drawing dating from about 1826 of a labyrinth from Pennsylvania was found in the Harmony Society Archives [Fig. 6]. It was probably intended for the garden at New Harmony, founded by the Rappites, a utopian, celibate religious community that emigrated in 1800 from Germany to avoid religious persecution and founded three settlements, Harmony and Economy in Pennsylvania and New Harmony in Indiana. The garden had a profound religious symbolism for this millennialist group. At the founding of each new settlement, members first laid out and planted a labyrinth and a botanic garden.[13]

The selection here includes familiar images reproduced in every study of American gardens, Mount Vernon and Monticello. These plantations of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were famous even in the owners’ lifetimes. Jefferson’s home was so often invaded by the public that he sought refuge at his daughter’s house, Poplar Forest,[14] which he also designed. These landscapes were well documented, immediately famous, historically significant sites, and, therefore, the surviving physical evidence is abundant as are representations, both visual and textual. It is about them that so much American garden history has been written. The field of historical garden archaeology began here.[15]

The apparent scarcity of early American material (in comparison to European accounts during the same period) leads one to wonder about the amount of garden activity. The majority of early writings on American gardens begin by stating that early colonists were too busy defending themselves from hostile natives and environments to care about gardens.[16] Can this be true? Maybe we just have not done enough work to uncover the evidence of gardening in the earliest period. Perhaps we must redefine what a garden is or was. Maybe we have not asked the right questions. Are we looking for amateur provincial versions of European gardens or a radically new way of exercising control over space and nature? How did the first Euro-American garden differ from its predecessors in intention, meaning, or function? If the garden is the most eloquent expression of complex cultural ideas, as John Dixon Hunt has written, is it a question of reidentification, or is it the creation of a new self-image?[17] We must question whether colonists’ perceptions were reshaped or radically changed because of the conditions of the New World, or whether they experienced the New World as Europeans, already formed by cultural conventions, preadapted to respond to their new surroundings.

One of the earliest views of a garden in the New World is by John White, an artist for Sir Walter Raleigh, who drew the Indian village of Secoton in Virginia, c. 1585 [Fig. 7]. Colonial artists rarely chose to depict the American landscape devoid of human activity and settlement.[18] Did the pictorial neglect of wilderness, which we know they experienced, result from a lack of interest in the physical environment of the New World, or from a vested interest in representing that environment as structured rather than chaotic? It is significant that a printed version of White’s drawing engraved by German engraver Theodor de Bry shows a further structuring of the images by a visual convention or language [Fig. 8]. As Wayne Franklin has written in connection with the early narratives and images of New World discovery, “[V]isual design, like the grammar of Old World language, was used to give American facts a composure they seem to lack on their own.”[19] Were artists unfamiliar with the pictorial conventions that would have allowed them to represent in two dimensions what they were witnessing? Amy Meyers has argued that artists made use of traditional ordering systems to depict the physical environment of North America as an extension of the structure of the known world.[20] If this was true of the two-dimensional representation of the landscape, was it also true of the three-dimensional organization of space?

William Bartram, in his writings on and images of natural history, was one of the first artists/naturalists whose work shows original and innovative means of representing the natural world. His Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida (1791) is a groundbreaking work because it offered a new way of describing in words and images the environment in which he lived.[21] He wrote that he was “wholly engaged in the contemplation of the unlimited, varied, and truly astonishing native wild scenes of landscape and perspective, there exhibited: how is the mind agitated and bewildered, at being thus, as it were, placed on the borders of a new world!”[22] What does this have to do with the design of ornamental gardens and our interest in recovering its history? I would suggest that we cannot separate the experience and representation of nature from that of landscape and gardens. There is a continuum that must be recognized: a network of naturalists/artists/botanists and gardeners who were behind the creation of American landscapes and gardens.

The early American settler did garden for “pleasure and for profit.”[23] Recent research into early American horticulture and cultivation practices from New England to the deep South has shown that the preindustrial mentality and economy of the region were as centered on plant cultivation and plant material extraction as on animal husbandry for food, fabrics, medicines, ornaments, poetic images, shelter, and manufactories.[24] The sample of early American gardens available to us is not necessarily what a majority of colonists and early Americans would have selected or even understood as representative. Garden historians have traditionally examined only a small fraction of the documents, citations, and evidence of landscape attitudes that exist. When these documents do not fully represent the majority of men and women in the historical period, we must turn from the verbal to the visual to access a class of garden makers who otherwise remain voiceless, such as women, servants, and immigrants. Even for well-known sites such as Monticello and Mount Vernon materials exist that have not fully been incorporated into the interpretation of their designed landscapes: for example, surveys done by their owners, who are representative of the cultural elite that was deeply involved in creating American landscape taste and in molding the landscape itself [Fig. 9].

American garden research has presented several historiographic problems. First is the record of scholarly comparison with European garden traditions, beginning with Andrew Jackson Downing himself, the so-called father of American landscape architecture. The chapter entitled “Historical Sketches” in his Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1841) is one of the earliest American histories of gardens. The book’s premise is that landscape gardening was created in England, and it is to England that Americans must look for standards. We have this historiographic perspective because Downing and his followers took specifically European creations—English landscape garden and rural architecture—and made minor and more far-reaching adaptations to suit them to the local scene. This is a case of deliberate cultural borrowing and adaptation for a particular audience that was still oriented toward Europe. Garden history that developed out of this context has seen American gardens in a clear line of descent from European, especially English, models. The progression of clearly identifiable movements of taste that has characterized English garden history, however, has never really applied to the history of American gardens. Even Downing had trouble with it because of the peculiarly American commitment to classical style and emphasis on ornamental horticulture, which were counter to the newer, irregular, modern style. The kind of history that relies solely on such a theory of gardens can be at odds with practice as we have come to know it through contemporaneous texts and images.

The practical use of American garden representations in images can be problematical when reconstruction and preservation are based on European models and on an anachronistic or irrelevant vocabulary. One of the most infamous examples is in Williamsburg, Virginia, a 1930s reconstruction that relied heavily upon one print, the so-called Bodleian plate (c. 1740) [Fig. 10]. The outcome was a wholesale re-creation in the early 20th century of the maze at Hampton Court and Dutch-English parterre garden with geometric topiary, resulting in a caricature of a grand style garden in colonial Virginia.[25]

The history of the 18th-century garden has been dominated by the concepts of the picturesque and the sublime, philosophical categories that pervaded all forms of literary and visual arts. Early American gardens of the same period have been dismissed for not participating in this discourse, and have generally been seen as purely utilitarian endeavors until late in the 18th century. Thereafter they are often characterized as rétardataire in relation to European garden practice. A more accurate history would stress that the art and science of garden making on both sides of the ocean were influenced by transatlantic gardening culture. Interest in plant material was shared by collectors in England and America, and its successful pursuit was fully interdependent and collaborative. The interaction was the exchange of drawings, descriptions, and specimens. A better understanding of the American garden is, therefore, essential to building a comprehensive history of the European garden during this period of interaction. American gardens provided living laboratories for experiments in naturalizing plants, studies for artistic depictions, and venues for the distribution of seeds and plants locally and internationally.[26]

The second historiographic problem is one of what might be called “stylistic monotheism,” or a misunderstanding of the multiplicity of stylistic innovation. It can be illustrated in the period of the Revolutionary War with the works, writings, and drawings of William Bartram, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Washington, and Jefferson. In his “Essay on Landscape, Explained in Tinted Drawings” (1798–99), Latrobe, the British architect who had recently immigrated to America, discussed landscape design beginning with the 17th and 18th centuries, when it was the fashion “to admit nature in every shape but her own.”[27] With a sketch of men and women in a formal garden [Fig. 11], Latrobe illustrated the predilection for topiary and trimmed planting:

In an age, in which the elegant forms of the Ladies were cooped up in Whalebone stays, and fenced in by the vast circumference of a hoop, when the Men were confined by ten dozen of Buttons and smothered by enormous wigs; it would be unreasonable in the trees to have complained of being cut into Cones and Pyramids, twisted into spires, and clipped into Lions and Elephants.[28]

Latrobe’s essay on landscape painting is, for garden historians, a fundamental text on early republican aesthetics. In it he ties together landscape aesthetics as expressed in gardens and paintings. He both subscribed to greater naturalism in landscaping and appreciated New World flora and topography. He believed the new environment demanded new treatment:

In America we have been, in our taste in Gardening, a little behind our scale of improvement in other respects. Till very lately we still loved straight unshaded Walks, and called them a Garden, and the few trees about our dwellings which escaped the axe, we robbed of their best property—that of shading us from the scorching sun. The rage of trimming our trees still subsists. . . the Sketch. . . on the page show[s] the contrast of the benevolence of nature, and the ingenuity of Man. Under the spreading oak on the left. . . the day is shady and cool, to the right may be easily recognized the old arrangement of a Virginian plantation [Figs. 12 and 13].[29]

Thomas Jefferson sympathized with Latrobe’s ideas of landscaping, which he thought should be suited to the requirements of the environment and not merely represent the latest British taste. In a letter to another gardener he contrasted garden design in England and the American South:

Their sunless climate has permitted them to adopt what is certainly a beauty of the very first order in landscape. Their canvas is of open ground, variegated with clumps of trees distributed with taste. They need no more of wood than will serve to embrace a lawn or a glade. But under the beaming, constant and almost vertical sun of Virginia, shade is our Elysium. In the absence of this no beauty of the eye can be enjoyed.[30]

It is useful to think about the interaction of these gardeners and garden theorists with one another. It reveals something of the heterogeneity of landscape taste at a moment in American garden history. It should caution us against generalizing. When George Washington saw the famous garden of the botanist John Bartram of Philadelphia, he complained that “it was not laid off with much taste nor was it large.”[31] The general, in the process of landscaping his own plantation, Mount Vernon, had collected a great deal of plant material from Bartram, yet he did not appreciate Bartram’s scientific approach to gardening, which stretched beyond the immediate grounds surrounding his house. Bartram had been described by another botanist, Alexander Garden, as being unsatisfied with a garden “less than Pensylvania & Every den is an Arbour, Every run of water, a Canal, & every small level Spot, a Parterre, where he nurses up some of his Idol Flowers & cultivates his darling productions.”[32] Bartram planted many of his rare species not only in this garden but in the two to three hundred acres of woods surrounding his house. Washington was not considering where Bartram had planted his botanical discoveries, which were in spots closely resembling the wilderness in which he had originally collected them.

Mount Vernon, in contrast, was laid out in what a contemporary visitor called the “English style”: “The general had never left America; but when one sees his house and his garden it seems as if he had copied the best samples of the grand old homesteads of England.”[33] When Latrobe, who had seen the gardens of England, visited Mount Vernon in 1797, he found it representative of an old-fashioned taste. He wrote in his journal, “For the first time since I left Germany, I saw here a parterre, chipped and trimmed with infinite care into the form of a richly flourished Fleur de Lis: The expiring groans I hope of our Grandfather’s pedantry.”[34]

Latrobe’s drawings of Mount Vernon tell a different story, however. This series of lovely watercolors composed from a side vantage point, depict the sloping lawn, the irregular terrain, and the distant views but not the symmetry and artificiality of the parterre [Fig. 14]. Latrobe emphasized the features of Mount Vernon that he found beautiful. He pictured the president and his family on the portico looking like neoclassical sculpture. It seems the offending beds of geometrical shapes remained popular in North America long after they had gone out of fashion abroad. His many sketches of sites he visited and recorded in his first years in America, always depict them from an angle or perspective that avoids any symmetrical views, in spite of the overall bilateral symmetry of their actual sites.

Having said this about Latrobe’s aesthetic or stylistic preference as seen through his travel sketches and journals, let us look at his proposal for a public square in New Orleans, which he made in 1819 [Fig. 15]. It shows a circular basin and symmetrically disposed allées of trees. This highly geometric scheme was in the style that Latrobe had criticized at Mount Vernon. For this public space, however, he seems to have preferred the geometric, regular, or, as it was also called, the French or ancient style. Latrobe’s neoclassical square implied a politically and socially homogenous body. Later, A. J. Downing explained in his Treatise why the ancient mode was appropriate for public design: It was associated with Grecian art and linked with the “agitation of politics and a life passed chiefly in public.”[35]

Over time, the modern or rural aesthetic found in domestic settings gained popularity because of the shift to a new ideal of man’s relationship to Nature, which was strengthened by the Transcendentalist movement and by the notion that individual contact with Nature and private experience of its beauties were desirable. It was this new aesthetic for both public and private parks that would dominate 19th-century design, initiated and epitomized in the rural cemetery movement but not to the exclusion of alternative styles.

The complex of stylistic approaches and attitudes coexisting in American design from the colonial period throughout the 19th century is summarized in a set of drawings for the layout of the grounds of the Elias Hasket Derby house (c. 1799), in Salem, Massachusetts. They are three alternative plans for the treatment of a garden surrounding a house [Figs. 16–18]. They represent the range of possibilities available, from the bilaterally symmetrical garden to the wilderness outside the door. Such drawings challenge our notion of a succession of styles moving from the geometric to the naturalistic.

In garden history, as in all history, much of what we know has been shaped by a dominant class and by specialized professions operating to a large extent within their own terms.[36] This study undertakes in part to correct or balance a third problem in the historiography of the American landscape, which is the bias toward the elite and upper class. The attention given to key figures such as Jefferson and Washington is supplemented with considerations of the contributions made by a range of owners, visitors, gardeners, nurserymen, and others who were active in the creation or maintenance and appreciation of gardens. An understanding of the roles of all of these, regardless of social class or level of training, must depend not on an uncritical review of meanings but rather on an analysis of the shaping and reshaping of vocabulary in the texts and images complied.

The owners, designers, users, and critics of gardens and landscape are all valid speakers for the meaning and function of gardens. It is essential to investigate contributions to garden theory and practice in America other than those made by the Washingtons, Jeffersons, Downings, and Olmsteds. They include the depiction of landscape in portraiture, for example, particularly by a painter like Ralph Earl (1751–1801), who succeeded in cultivating a taste for regional landscape views among his patrons. A trademark of his portraits was the detailed landscape and garden view; he frequently included his patrons’ newly constructed houses and improved lands, which appear as window vignettes or as backdrops in his portraits [Fig. 19]. As a result of the popularity of his portraits, Earl received commissions to paint pure landscapes in the latter part of the 1790s.[37] Similarly, Charles Willson Peale’s portrait of William Paca was used in the reconstruction of the summer house and Chinese bridge at the Paca garden in Annapolis.[38]

A fourth problem is the definition of the American garden or designed landscape. The project has attempted to overcome any narrowness resulting from the limitations imposed by geographic bias and by traditional definitions of a garden. HEALD considers all kinds of gardens and designed landscapes, such as town planning, the private garden, parks and public gardens, and the institutional garden. Also relevant are materials related to horticultural trade and distribution, scientific agriculture, and the emergence of a landscape profession.

The HEALD project began with questions about how do we know what we know about American gardens and landscapes, and with questions concerning the nature of the evidence we use in the interpretation of that history. A goal of this work is to understand better the history of the designed environment as a means to understanding the culture of our own environment. Dell Upton has addressed the issue of how to study the built environment in terms that are useful to the study of the designed landscape. Rather than examine simple relationships between mental intention and physical creations, that is, between a mind and an artifact, the study of the designed landscape or garden ought to investigate the reciprocal relationships between ourselves and human alterations of the environment. It must take into account intention and reaction, action and interpretation.[39] Upton emphasizes how profoundly our built world is the product of our thought because it is that sector of our physical environment that we modify through culturally determined behavior.

Garden history analysis can make a distinct contribution to understanding the designed landscape by probing the experience of the garden, of which intentional creation is only one element. By analyzing physical garden remains in terms of their surviving representations, we can say something about the ways we have constructed ourselves in space and in relationship to the natural environment. Surviving representations, both texts and images, are documents that can enrich our study of the American garden, but only if we recognize that the languages, verbal and visual, are historically and culturally determined. Each example or case study that we approach produces results that were intended and many that were not, requiring continual reconceptions of representations of the landscape.

Notes

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller, Sidney Hart, and David C. Ward, eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family: The Belfield Farm Years, 1810–1820 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), 3:216, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “Charles Willson Peale’s Belfield, Its Place in American Garden History,” in New Perspectives on Charles Willson Peale, ed. Lillian B. Miller and David C. Ward (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press for the Smithsonian Institution, 1991), 267–81, view on Zotero.

- ↑ O’Malley in Miller and Ward 1991, 271, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “Appropriation and Adaptation: Early Gardening Literature in America,” Huntington Quarterly 55 (summer 1992): 401–31, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Eliza Lucas Pinckney, The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 1739–1762, ed. Elise Pinckney (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972), 61, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976), 20–21, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Batty Langley, New Principles of Gardening (London: Bettesworth, Barley, Pemberton, Bowles, Clarke and J. Bowles, 1728), view on Zotero; Philip Miller, The Gardeners Dictionary (London: The Author, 1731), view on Zotero, and J. C. [John Claudius] Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ O’Malley, “Appropriation and Adaptation,” 401–31, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Donald W. Meinig, “Symbolic Landscapes,” in The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographic Essays, ed. Donald W. Meinig (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979), 188.

- ↑ W. J. T. Mitchell, ed., Landscape and Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 2, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James D. Kornwolf, Architecture and Town Planning in Colonial North America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 833–35, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For a discussion of the interpretation of the documents surrounding the restoration of the palace gardens see Catherine Howett, “Integrity as a Value in Cultural Landscape,” in Preserving Cultural Landscapes in America, ed. Arnold R. Alanen and Robert Z. Melnick (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 195–97, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lee Ann DeCunzo, et al., “Father Rapp’s Garden at Economy: Harmony Society and Culture in Microcosm,” in Landscape Archaeology: Reading and Interpreting the American Historical Landscape, ed. Rebecca Yamin and Karen Bescherer Metheny (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996), 91–117, view on Zotero.

- ↑ S. Allen Chambers Jr., Poplar Forest and Thomas Jefferson (Forest, VA: Corporation for Jefferson’s Poplar Forest, 1993), x, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William M. Kelso, “Landscape Archaeology and Garden History Research: Success and Promise at Bacon’s Castle, Monticello, and Poplar Forest, Virginia,” in Garden History: Issues, Approaches, Methods, ed. John Dixon Hunt (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1992), 31–57, view on Zotero.

- ↑ See, for example, the entry “United States,” in Candice A. Shoemaker, ed., Encyclopedia of Gardens: History and Design (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2001), 3:1339, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Dixon Hunt, Gardens and the Picturesque: Studies in the History of Landscape Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992), 3, view on Zotero.

- ↑ See the caption to plate 17 in Wayne Franklin, Discoverers, Explorers, Settlers: The Diligent Writers of Early America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Franklin 1979, from the introduction to the plates, following 209, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Amy R. W. Meyers, “Imposing Order on the Wilderness: Natural History Illustration and Landscape Portrayal,” in Views and Visions: American Landscape before 1830, ed. Edward J. Nygren with Bruce Robertson (Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1986), 112, view on Zotero.

- ↑ This is the subject of Amy Meyers’s dissertation, “Sketches from the Wilderness: Changing Conceptions of Nature in American Natural History Illustration: 1680–1880” (PhD diss., Yale University, 1985), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bartram, Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, ed. Mark Van Doren (New York: Dover, 1928), 166, view on Zotero.

- ↑ In the first decade of the 18th century, William Byrd had 20,000 acres on which he grew pomegranates and other Mediterranean plants. See Kornwolf 2002, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter Benes, “Horticultural Importers and Nurserymen in Boston, 1719–1770,” in Plants and People: Annual Proceedings of the Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife, 1995, ed. Peter Benes (Boston: Boston University, 1996), 38–53, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For a discussion of the problems of reliability in European garden history, see Dianne Harris and David L. Hays, “On the Use and Misuse of Historical Landscape Views,” in Representing Landscape Architecture, ed. Marc Treib (London and New York: Taylor and Francis, 2008), 22–41, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “Mark Catesby and the Culture of Gardens,” in Empire’s Nature: Mark Catesby’s New World Vision, ed. Amy R. W. Meyers and Margaret Beck Pritchard (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 149, view on Zotero. For a study of how both American and foreign horticulturalists shaped the landscape over the past 250 years, see Philip J. Pauly, Fruits and Plains: The Horticultural Transformation of America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Henry Latrobe, The Virginia Journals of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1795–1798, ed. Edward C. Carter II (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977), 2:500, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Latrobe 1977, 2:500, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Latrobe 1977, 2:500, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jefferson to William Hamilton, July 1806. Cited in Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), 323–24, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Washington on Bartram’s garden, cited in George Washington, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745–1799, ed. John C. Fitzpatrick (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1931–44), 2:431, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Garden on Bartram’s garden, cited in Cadwallader Colden, The Letters and Papers of Cadwallader Colden (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1918–37), 472, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Julian Niemcewicz, in 1798, quoted in Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia, from Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), 135, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Henry Latrobe, The Virginia Journals of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1795–1798, ed. Edward C. Carter II (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977), 1:165, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Williams 1976, 24, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, et al., Ralph Earl: The Face of the Young Republic (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1991), 56–60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ On the other hand, Peale painted Margaret Tilghman Carroll at Mount Clare in Baltimore in 1770–88 with only a generic classical urn in the background. It was Mrs. Carroll, however, who was responsible for the great gardens at Mount Clare, whose greenhouses George Washington admired and copied at Mount Vernon. These are all examples of the landed elite whose traces are well documented. It is far more difficult for those speakers without any voices, such as enslaved people and women. Mrs. Carroll was an exception. Carmen A. Weber, “The Greenhouse Effect: Gender-Related Traditions in Eighteenth-Century Gardening,” in Yamin and Metheny 1996, 32–51, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Dell Upton, “Pattern Books and Professionalism: Aspects of the Transformation of Domestic Architecture in America, 1800–1860,” Winterthur Portfolio 19 (1984): 107–50, view on Zotero.