Blithewood

Situated on a bluff overlooking the Hudson River, Blithewood brought together some of the most famous architects and landscape gardeners of early nineteenth-century America under the patronage of Robert and Susan Gaston Donaldson. Between 1835 and 1853, American and European publications described, praised, and illustrated the farm, pleasure grounds, and ornamental gardens of the property. Plans and woodcut reproductions of the house, gardens, and outbuildings inspired patrons of rural estates and shaped the language of American picturesque landscapes.

Overview

Alternate Names: Mill Hill; Annandale; Annandale-on-Hudson; Blithe Wood; Blythe Wood; Blithwood; Blythewood

Site Dates: 1795 to present

Site Owner(s): Barent van Benthuysen (1725–1795?); John and Alida Livingston Armstrong (1795–1801); John and Mary Johnston Allen (1801–1810); John Cox Stevens and Maria Cambridge Livingston (1810–1833); John Church Cruger (1833–1835); Robert and Susan Gaston Donaldson (1835–1853); John and Margaret Johnston Bard (1853–1897); Saint Stephen’s College (1897–1899); Captain Andrew Christian and Frances Hunter Zabriskie (1899–1916); Frances Hunter Zabriskie (1916–1951); Bard College (1951–present)

Associated People: Walter Elder (gardener), George Kidd (gardener), Andrew Jackson Downing (landscape gardener), Alexander Jackson Davis (architect), Hans Jacob Ehlers (landscape gardener)

Location: Dutchess County, NY

Condition: altered

View on Google maps

History

Between 1795 and 1836 the property that would come to be known as Blithewood exchanged hands several times. Several of its owners were connected by birth or by marriage to the Livingston and Armstrong families. In 1795, the soldier and politician John Armstrong (1758–1843) and his wife Alida Livingston Armstrong (1761–1822) purchased a 125-acre estate, which they named Mill Hill. The Armstrongs built a Federal-style house on the property and developed the land as a farm. John and Mary Johnston Allen bought the estate in 1801, which they called Annandale after the Scottish ancestral home of Mary’s family. In 1810, John Cox Stevens (1785–1857), best known as the founder of the New York Yacht Club, and his wife Maria Cambridge Livingston (1799–1865) acquired the property. Stevens was later credited with planting some of the most impressive trees on the estate. One 1856 article went so far as to call his trees “a successful instance of planting attaining perfection in the lifetime of a single individual” (view text). In 1833, the lawyer John Church Cruger purchased Mill Hill and the adjacent peninsula, on which he built his own country seat, known as Cruger’s Island. Two years later, in 1835, Cruger sold the southern part of his property to the banker Robert Donaldson (1800–1872) and his wife Susan Gaston (1808–1866), who renamed the estate Blithewood.

Upon purchasing the estate, Donaldson hired the architect Alexander Jackson Davis (1803–1892) to renovate the existing house as an ornamental cottage, and design a new gatehouse, later used as a gardener’s house. Davis and Donaldson collaborated closely on the design, and the two would go on to create other outbuildings for Blithewood including a spring house, an Egyptian revival toolhouse, assorted picturesque seats, and a hermitage.[1] Their collaborations are well illustrated by Davis’s many surviving ink and watercolor preparatory drawings [Fig.1]. In 1841, Davis negotiated a joint purchase of the Sawkill Creek, which ran between Blithewood and its neighboring estate, Louise Livingston’s Montgomery Place, to ensure that the southern border of his property would not be marred by “the countless vexations & annoyances of Factories.”[2] That same year, Blithewood received lavish praise in the first edition of Downing’s Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, a description which was quickly reprinted abroad in respected journals like John Claudius Loudon’s The Gardener's Magazine.[3] Downing described “delightful walks leading in easy curves to rustic seats, summer houses, etc. disposed in secluded spots, or to openings affording the most lovely prospects,” and “Maltese vases” that were “disposed in such a manner as to give a classic air to the grounds” (view text). The rustic, picturesque aesthetic was complemented by the gothic-influenced “English cottage style” of Donaldson’s early additions.[4]

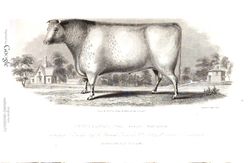

A working farm on the property provided food for the estate and space for experimental animal husbandry. In 1845, the agricultural journal the Cultivator published a print of Donaldson’s short-horn bull Prince Albert, probably based on a drawing by Davis [Fig. 2].[5] The bull looms over the new gardener’s cottage and hexagonal gatehouse at Blithewood, uniting the agricultural, horticultural, and social functions of the estate. In 1848, a cow named Kaatskill who had already gained celebrity in 1844, was depicted in the New England Farmer standing in front of a cascade, which evokes the dramatic topography of the Sawkill Creek between Blithewood and Montgomery Place.[6]

The Donaldsons began designing and planting an ornamental garden at Blithewood in 1844. A visitor in 1845 described how the topography of the site required “terracing the eastern declivity of a hill” with “substantial stone walls,” and went on to marvel at the “extensive conservatory and grape-house” and “rich profusion of flowers and shrubbery. . . .and various labyrinthine walks and shady bowers” (view text). A year later, an article in the March 1846 edition of the American Agriculturist described a finished garden “in the geometric style, [. . . .] concealed by hedges and shrubbery. The upper plateau is devoted to fruits and flowers, and the terraces are given up to vegetables. The green-house and fruit houses, 90 feet long, are so arranged as to present a very handsome architectural appearance. Besides a great variety of foreign grapes, the fig, apricot, nectarine, plum, and peach, are grown in these houses as espaliers, and dwarf standards.” Davis’s undated watercolor plan of the property differentiates wooded areas from open lawns, and indicates several different types of drives and paths through the use of color and outlining [Fig. 3]. Labelled elements include a boathouse on the river, a rustic tent, a cataract, a barn, a grass field, and two springs.

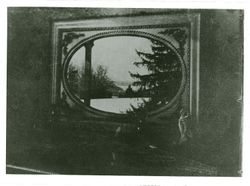

The picturesque ideal that motivated Donaldson and his collaborators also prompted the inclusion of a unique architectural element in the picture gallery that was added to the main house in 1845. Amid the painted portraits and landscapes of the Donaldson art collection, visitors marveled at “the Landscape Window, a novelty introduced by Mr. D., which quite took us by surprise. It is an oval plate glass, 3 by 4½ feet, inserted in the wall, and surrounded by rich mouldings, in imitation of a picture frame. One feels that the natural beauties here revealed surpass even the glowing compositions [of the paintings that surround it]” (view text). This self-conscious presentation of the grounds, the Hudson, and the mountains beyond as if they were elements of a skillfully composed painting [Fig. 4] blurred the line between art and nature. At times the picturesque landscape appeared unkempt. Downing implied in 1847 that the lawns at Blithewood were not “well kept” when he advised Donaldson to “mow regularly every fortnight” (view text).

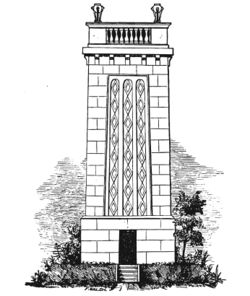

Supported by Donaldson’s wealth, the gardeners at Blithewood were able to experiment with novel techniques and share their findings. One gardener in particular, named George Kidd, was especially prolific in this regard. He submitted a letter about his success growing potted grapes in greenhouses (view text) and another about kitchen gardens to the Horticulturist in 1848, both with a practical eye toward localizing garden theory and practice for the colder climate of the Hudson.[7] Another one of his communications, published in 1849-1850, shared new techniques for cultivating roses.[8] Donaldson himself helped spread the knowledge he gained transforming Blithewood. His short letter to the Horticulturist, published in 1853, describes the design and hydraulic engineering of a forty-five-foot-tall “tower in the form of an Italian campanile” at Blithewood [Fig. 5]. This disguised water tower, which was filled by the Sawkill Creek, supplied water for “irrigation, the cattle yard, stable, the garden, the house and fountains” and served “also as a prospect tower” (view text).

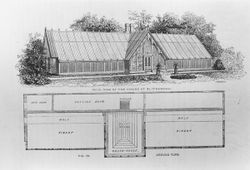

Thanks to such articles, published in magazines like The Cultivator and the Magazine of Horticulture, Botany and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs, mechanical and architectural prototypes employed at Blithewood were publicized in the American northeast and adapted for new sites and contexts. One 1845 article described a novel plow designed to cut picturesque walks exactly three-and-a-half feet wide (view text) [Fig. 6]. While the device was purportedly first used within the region at William B. Astor’s villa, gardeners learned of it in articles about Blithewood. Downing published a view and plan of the greenhouse at Blithewood in an 1846 issue of the Horticulturist (view text) [See Fig. 12]. Two years later, Samuel Bigelow (1807–after 1898) relied on these descriptions and drawings when he designed and built a new greenhouse “upon the plan of one at Blithewood” at his estate in Brighton, Massachusetts ().[9]

By 1848, Blithewood was so firmly established in the circles of American landscape gardening that writers could use it as a point of reference when describing less well-known estates.[10] It also gained international exposure thanks to publications like the 1853 Homes of the New World by Swedish writer Frederika Bremer (1801–1865), in which she recounted her visit to the estate with Downing in 1849 (view text). During their explorations of the surrounding area, visitors like Bremer were astonished by a false ruin on John Church Cruger’s peninsula to the north of Blithewood, known as “Cruger’s folly,” which incorporated real fragments of Mayan sculpture.[11]

Downing’s use of Blithewood as an exemplar of good taste in landscape gardening also unintentionally marked it as a target for his own critics. Most vocal among these was the German landscape gardener Hans Jacob Ehlers, who worked for a number of prominent garden patrons in the Hudson Valley. When Ehlers became embroiled in a dispute with Cora and Thomas Barton, owners of the neighboring Montgomery Place, he attacked Downing’s credentials as an arbiter of taste by singling out his illustrations and descriptions of Blithewood. Ehlers criticized the design of the estate, asserting that trees surrounded the main house as if it were “a privy” the gardener sought to hide, that the walks resembled “ditches, hardly fit for cattle to walk in,” and, most importantly, that “there are at Blithwood [sic] no points accessible and decent, from which a picturesque view can be obtained” (view text). In Ehlers’s view, Davis’s illustration of the property [See Fig. 7], selected by Downing as a frontispiece for his Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, was a dishonest, composite image that combined multiple points of view into a composition more picturesque than any single vista on the property. Ehlers’s skeptical criticism of the estate and its depictions demonstrates how Blithewood became central to disputes about the veracity and taste of Downing’s didactic illustrations.

Donaldson sold Blithewood to John Bard in 1853, one year after Downing’s death, and moved to an 1820s Greek revival mansion at Barrytown known as Edgewater. John, the grandson of the famous physician Samuel Bard of Hyde Park, renamed the estate Annandale (or Annandale-on-Hudson), and within a decade of his purchase he made several major alterations to the property. In 1856, he donated part of the grounds to found an Episcopalian seminary named St. Stephen’s College. On the land that he retained, he constructed new “conservatories and forcing houses” and planned a much larger residence (view text). In 1899, Captain Andrew C. and Frances Hunter Zabriskie bought the property, demolished the Donaldson house, and built a neoclassical mansion. Around the year 1903, the Zabriskies commissioned Francis Hoppin (1867–1941) to design a new Italianate garden called Blithewood in homage to Donaldson’s earlier picturesque estate. The property was acquired by Bard College in 1951.

—Alexander Brey

Texts

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1841, describing the landscape at Blithewood (Downing 1841: 23)[12]

- “Blithewood, the seat of R. Donaldson, Esq. near Barrytown on the Hudson river, is one of the most tasteful villa residences in the Union. The lawn or park, which commands a view of surpassing beauty, is studded with groups of fine forest trees, beneath which are delightful walks leading in easy curves to rustic seats, summer houses, etc. disposed in secluded spots, or to openings affording the most lovely prospects [Fig.7]. In various situations near the house and upon the lawn, Maltese vases exquisitely sculptured in stone, are disposed in such a manner as to give a classic air to the grounds. The entrance lodge, built in the English cottage style, is exceedingly neat and appropriate, and the whole place may be considered quite a model of elegant arrangement; such indeed as may fairly come within the reach of numbers of our wealthy proprietors, did they possess the taste, as well as the means, for this species of refined enjoyment.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1844, description of Blithewood in the second edition of Downing’s Treatise (Downing 1844: 35–36)[13]

- “Blithewood, the seat of R. Donaldson, Esq. near Barrytown on the Hudson river, is one of the most charming villa residences in the Union. The natural scenery here, is nowhere surpassed in its enchanting union of softness and dignity—the river being four miles wide, its placid bosom broken only by islands and gleaming sails, and the horizon grandly closing in with the tall blue summits of the distant Kaatskills. The smiling, gently varied lawn is studded with groups and masses of fine forest and ornamental trees, beneath which are walks leading in easy curves to rustic seats, summer houses placed in secluded spots, or to openings affording the most lovely prospects [Fig. 7]. In various situations near the house and upon the lawn, sculptured vases of Maltese stone are also disposed in such a manner as to give a refined and classic air to the grounds.

- “As a pendant to this graceful landscape, there is within the grounds scenery of an opposite character, equally wild and picturesque—a fine, bold stream, fringed with woody banks, and dashing over several rocky cascades, thirty or forty feet in height, and falling, altogether, a hundred feet in half a mile [Fig. 8]. There are also, within the grounds, a pretty gardener’s lodge, in the rural cottage style, and a new entrance lodge by the gate, in the bracketted mode; in short, we can recall no pace of moderate extent, where nature, and tasteful art, are both so prodigal of beauty, and so harmonious in effect.”

- Anonymous, August 1845, “Our Plate—Mr. Donaldson’s Farm” (Cultivator 2: 249)[14] Back up to History

- “Few places that we have ever seen exhibit such marked evidence of refined taste, and correct appreciations of rural beauty, as BLITHEWOOD. The spot itself is one possessing great natural attractions, and these have been heightened and improved to the greatest possible advantage. It is a promontory on the east bank of the Hudson, embracing the greatest variety of magnificent landscape scenery of any spot of the same extent within our knowledge. The river here is of unusual width, and there are several pretty islands nearly opposite, by which the force of the current is so broken that the water has the placid quietness of a sheltered lake, and reflects with mirror-like vividness, every object on its banks, or floating on its surface. On the west side of the river, a little to the north-west, the Kaatskill group of mountains appear in all their majestic beauty, forming a grand, but varied and picturesque outline to the view for a considerable extent in that direction.

- “The mansion of Mr. Donaldson, constitutes the frontispiece to Mr. Downing’s elegant work on Landscape Gardening and Rural Architecture. Representations of several of the other buildings, as well as various sketches of the scenery at Blithewood are also given in Mr. Downing’s work, to which we would refer for a more particular description. The scenery in the background of our engraving, is copied from nature—the building on the right being the gate-lodge, and the one on the left the gardener’s cottage—the farm-yard building buildings with a grove in the rear, showing between.

- “The credit of introducing to this country the Rural Gothic, or pointed style of architecture, belongs to Mr. Donaldson. The first specimen of this style was the gardener’s cottage above-mentioned, which, for its taste and simplicity, excels anything of the kind we have ever seen. Mr. Donaldson was also, we believe, the first to introduce what is called the Bracketted style, several pretty specimens of which are shown among his numerous buildings.

- “Mr. D.’s garden has been but lately laid out—the present being the first season that the principal portion of it has been appropriated to plants. To secure a favorable site, he has been under the necessity of terracing the eastern declivity of a hill, and forming a soil somewhat artificially. The terraces are formed in a beautiful manner, supported by the most substantial stone walls. An extensive conservatory and grape-house has just been erected, in the most tasteful style. A rich profusion of flowers and shrubbery adorn the garden, and various labyrinthine walks and shady bowers.

- “The soil of Mr. Donaldson’s farm has been much improved, and its productiveness vastly increased, since he came into possession of it, about nine years ago. His outside fences are mostly stone walls, laid in the most systematic and durable manner. His wet grounds, of which there is a considerable portion, have been mostly under-drained, and latterly he has commenced subsoiling which promises to be of great benefit, particularly to the tenacious soil. A piece of oats on some of the under-drained land, is about the best we have seen this season. His barn is constructed on a convenient plan; his barnyard is well protected by sheds, and is well contrived for making and saving manure. His young cattle are not pastured by soiled. They are fed in the sheds and yard, mostly with mowed grass, and are allowed the run of a small shady lot. They are in good order, an appear healthy and thrifty.

- “We saw here a superior machine for cleaning walks, invented by Mr. Donaldson. Its general form, is that of the frame of a wheel-barrow. Two bars of iron, representing the legs, reach down to the ground, and attached to the bottom of them is a transverse bar of steel, about two and a half inches wide, one edge of which is made sharp. Three or four inches of the lower end of the upright bars are also made sharp, in order to cut the sides of the walk. The handles are held by a man, and the machine is drawn by a horse. A space three-and-a-half feet wide is shaved at once, the man at the handles regulating the working of the implement so as effectually to cut up the weeds and grass. It is to be recommended for its simplicity and efficiency.”

- Anonymous, March 1846, “Farm and Villa of Mr. Donaldson” (American Agriculturist 5, no. 3: 88–90)[15]

- “FARM AND VILLA OF MR. DONALDSON.

- “WITHIN the past ten years, there has been quite a revolution in the Northern States with respect to country life; it is now rapidly assuming here the rank it has so long held in Great Britain, and in some parts of the Continent. In England, especially where the love of rural pleasures pervades all classes, the most affluent and noble of the land seem to consider their town houses as merely temporary accommodations during the whirl of the fashionable season, and the sitting of Parliament, after which they fondly return to their ancestral castles, where for many generations all that wealth, taste, and skill could contribute, have been accumulating to make their homes desirable. [. . . .]

- “Blithewood, the residence of Robert Donaldson, Esq. is situated in Dutchess County, on the Hudson river, about a hundred miles above this city. It was formerly the seat of General Armstrong, of Revolutionary memory, who was Secretary of War under Mr. Madison. [. . . .]

- “To visit Blithewood, we landed at Barrytown, two miles below, and in approaching it, the gatehouse or lodge [Fig. 9] was the first object tha[t] attracted our attention. It is a hexagonal brick building, stuccoed and colored in imitation of freestone; and strikingly placed on a terrace in the midst of a group of forest trees, it is no less ornamental than useful. An excellent macademized road leads through the estate from the lodge to the mansion.

- “Soon after entering the gate, we lose sight of all boundary walls and fences, and pass the gardener’s house [Fig. 10]. This is in the Cottage Gothic style, and with its pointed and projecting gables, and miniature porch, covered with honeysuckles and Boussault roses, it has a very neat and pretty appearance.

- “Approaching the house, the road winds among white pines, through which may be seen the graceful slopes of the grounds, and the noble masses of wood. The view which is disclosed, as you sweep round to the river front, assures you that nature has been lavish of her beauties here. Our readers will get a very good idea of the view presented at this point by looking at the frontispiece to Downing’s Landscape Gardening and Rural Architecture.

- “The Kaatskill mountains, on the opposite side of the river, reach a height of nearly 4,000 feet, and the range may be seen for fifty miles, clothed in the enchanting hues that distance ever lends to bold mountain scenery. The unusual width of the river here—the wooded isles—the promontories, with their quiet bays—the spires of the neighboring villages—the Mountain House—all combine to form a landscape of extraordinary attraction. The scenery along the Sawkill, which forms the southern boundary of this place, reminds one of Trenton Falls. The stream descends in cascades and rapids, 150 feet in a quarter of a mile. A lake has been formed about half way up its course, through the estate, the placid waters of which contrast finely with the rushing cataracts.

- “By an overshot water wheel which could be made ornamental, and a simple hydraulic machine, a portion of the water of this stream might be forced up to the adjoining height, and thence conducted to the house, garden, stables, and cattle yard; it might also be made to irrigate the grass land, and to form fish ponds, and jets d’eau.

- “The dwelling house is 160 feet above the river. It is a low, but most commodious structure, embosomed in trees, stuccoed and colored in imitation of freestone, with a deep verandah on three sides, and a boldly projecting and richly bracketted roof; and whatever may have been its original plan, it has been so enlarged and transformed by its present owner, as to present a most inviting aspect. The interior is very tastefully arranged, but on this we cannot enlarge, and confine ourselves to a description of the picture room—an apartment on the river side of the house, 16 by 32 feet, of a high pitch, and receiving its strongest light through an ornamented sash in the ceiling. In this choice, though limited collection, there are the Picnic Party in Epping Forest, by C. R. Leslie; a Landscape, by John Both; the Billet Doux, by Terburg; the Lute Lesson, by Gaspar Netcher; a most lovely Madonna and Child, supposed to be by Luini; the Physician and Invalid, by the elder Palamedes; the Benevolent Family, a highly finished painting, by a Flemish Master; together with some portraits by Leslie, and some carefully made copies of well known pictures. But more striking than all these is the Landscape Window, a novelty introduced by Mr. D., which quite took us by surprise. It is an oval plate glass, 3 by 4½ feet, inserted in the wall, and surrounded by rich mouldings, in imitation of a picture frame. One feels that the natural beauties here revealed surpass even the glowing compositions.

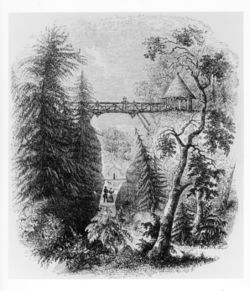

- “Walks lead away in the most alluring manner, for two miles, through the varying scenes of this place, along which rustic seats and pavilions are placed, at the best points of view. We give a view of one of them on the Sawkill [Fig. 11].

- “The spring house, which is in course of erection, on the verge of the spacious lawn, will be very ornamental. The water flows through a water lily, into a sculptured shell, from the scolloped [sic] lip of which it falls as from a dripping tazza.

- “The garden, which is in the geometric style, though near the house, is concealed by hedges and shrubbery. The upper plateau is devoted to fruits and flowers, and the terraces are given up to vegetables. The green-house and fruit houses, 90 feet long, are so arranged as to present a very handsome architectural appearance. Besides a great variety of foreign grapes, the fig, apricot, nectarine, plum, and peach, are grown in these houses as espaliers, and dwarf standards.

- “The Farm.—This comprises 125 acres. The soil varies from a sandy to a clayey loam. Parts of the outer lots, where the subsoil was so adhesive as to retain the surface soil, have been subdrained with the small stones gathered from the surface. These lots can now be worked at the earliest opening of spring; and though forming a very superior soil for grass; they yet yield very heavy crops of small grain. As an evidence of this, although the season of ‘45 was very unfavorable to oats, we here saw a lot which turned out 50 bushels to the acre. Since acquiring possession of this place, ten years since, Mr. D. has doubled the crops; and though he has occasionally used alluvial mud (limed) from the Sawkill, as a topdressing, and also plaster and ashes, and applied guano and poudrette to the hoed crops, with satisfactory results; yet his main reliance for keeping up the fertility of his place, has been the barnyard. To this place all weeds, fallen leaves, butts of cornstalks, and offal of the farm are gathered, and through these the wash of the barnyard leaches. We think Mr. D. has gone through unnecessary trouble and expense in plowing in manure on the slopes and banks to get them into grass, instead of pasturing South-down sheep, which might easily be done in hurdles. The growth of the sheep would in a single season defray the expense of the arrangement, and the sod would be left by them, topdressed and fertilized in the simplest and most efficient manner. We have often seen flocks of sheep pastured for this purpose on the lawns and finest estates in England.

- “The farm-buildings are judiciously placed near the centre of the land, and well constructed for sheltering the cattle and saving the manure. The boundary walls are well laid, and the expense and unsightliness of cross-fences have been greatly avoided by soiling most of the cattle. [. . . .]

- “We could say much more of Blithewood; but should any of our readers chance to visit it, they will feel how inadequate words are to convey an idea of its varied scenes, some of which are worthy of the pencil of Ruysdael or Claude.

- “Stucco.—We thought the Stucco used by Mr. D. in his buildings a superior kind, and copied his recipe for making it. Take pure beach sand, and add as much Thomaston lime as it will take up, then sufficient hydraulic cement to make it set, say about one-fifth of the whole mixture of sand and lime. To prevent cement attracting moisture, put a strip of sheet lead or zinc as wide as the foundation of the building over it, then lay up the walls. The walls should be hollow, as they are stronger than solid walls, and they save nearly one-third of the brick. The finishing plaster can then be laid on inside without the expense of furrowing out and lathing, as hollow walls are always dry. The stucco is also more lasting and not likely to peel. The stucco can be painted a handsome fawn color by dissolving burnt ochre in sweet milk.

- “We saw here a most useful labor-saving machine, first introduced at Mr. William B. Astor’s villa, for cleaning gravel walks. With this, a man, a boy, and a horse, may do the work of twenty men. We here annex an engraving of it. It is very simple in its construction, and costs about $10.

- “Mr. Downing has kindly permitted us to make casts of the illustrations above, from the cuts executed for his “Landscape Gardening and Rural Architecture,” a work which we cannot too highly and too often recommend to the public.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, August 1846, “The New Vinery at Blithewood” (Horticulturist 1, no. 2: 58)[16] Back up to History

- “The New Vinery at Blithewood, erected about eighteen months ago, we have had engraved as the frontispiece embellishment of the present number.

- “The glass structures in general use, both in this country and in England, it must be candidly confessed, are rather ugly and unsightly objects. They have frequently either the common-place glazed-shed appearance of a market gardener’s rude green-house, or the clumsy and heavy air imparted to them by some architect or builder, whose knowledge of the matter in hand is, at best, crude and imperfect.

- “The building which we now present our readers a view, [Fig. 12], strikes us as a happy exception to these remarks. To much simplicity of detail and excellent arrangement for its purpose, it adds a chaste and becoming architectural character, which gives it an air of elegance and finish in every way worthy of a handsome country seat.

- “With regard to the exterior, we think the proportions excellent. The slope of the roof, about 40°, is one of the best for this climate. There is a particularly light yet firm and pleasing effect in the structure of the rafters, and especially the upright glass in front. The chaste ornaments, which terminate the rafters at the eave and ridge lines, joined to the very tastefully decorated gables, strike us as producing a very elegan[t] and harmonious effect—greatly superior to anything of the kind we have yet seen attempted.

- “The length of this vinery is about 100 feet. Every one familiar with long uniform ranges of glass, is aware of a stiffness and monotony of effect in the exterior, which is by no means agreeable. In the present case, this is entirely avoided by a projecting compartment in the centre of the range. This central compartment is used as a green-house for choice plants. In it is placed the principal door, and supposing this portion of the range, which is comparatively a small one, filled with summer blooming plants, such as the new Fuchsias, Gloxinias, Achimenes, &c., which are so gay and bright from May to December, we hardly know a more beautiful vestibule to a vinery range, filled with luxuriant and prolific grapes.*

- “We should remark here that this range of glass is intended to be used as a cold vinery—that is, the grapes are to be grown without artificial heat. The perfection to which this mode of growing the Muscat of Alexandria, Black Hamburgh, &c., was carried in the old vinery at Blithewood, so well satisfied its proprietor, that he erected the present house for the same general plan of culture. Our sun in this latitude is at all times bright and powerful enough to mature the foreign grape perfectly, with the simple aid of glass and the power which it gives us of controlling the changes of the atmosphere, thus guarding against the too violent fluctuations to which we are often subject. The position of this vinery at Blithewood is remarkably good. It stands on the north boundary of the fruit garden, with a southern aspect, and is backed by a thick copse of wood; hence the rear of the building is never seen by the visitor, while the front appears to the best advantage. In a situation exposed on all sides, by doubling the rafters, forming a span roof, and pursuing the same general style, a very beautiful and perfect structure would be obtained for any purpose.

- “The ground plan, fig. 18, we believe almost sufficiently explains itself. The height of the roof, and the clear width of the vinery itself, are each about 15 feet. The width between the rafters, from centre to centre, is four feet. Underneath the stage in the green house, is a large cistern for the supply of the cold range with water. At the back of the range are a potting shed, and a fruit and seed room. The vines are planted in the usual mode—one beneath each rafter.

- “Most of our readers are already familiar, through the published views in our Landscape Gardening, with Blithewood, one of the most beautiful of American country seats, the residence of Robert Donaldson, Esq., situated on the east bank of the Hudson, about 100 miles from New-York. The present structure bears the same marks of superior taste and refinement in landscape embellishment and building, that we have before so gladly admired and commended in this demesne.”

- “*Or to those who care little for a green-house, this compartment might be used for forcing an early crop of grapes.”

- Kidd, George, November 1848, “Culture of Foreign Grapes in Pots” (Horticulturist 3, no. 5: 212–215)[17] Back up to History

- “As you solicit communications from horticulturists, I avail myself of a few moments of leisure, to offer some remarks on the culture of grapes in pots.

- “The article from the Gardeners’ Chronicle, reprinted in the September number of the Horticulturist, though able, is unsuited in its detail to this climate. Your humble servant, having been educated in the same school with the writer of the article in the Gardener’s Chronicle, in giving his own practice, will not be found to differ in principle, but merely to Americanize the practice. . . .

- “Mr. Donaldson, the proprietor of Blithewood, has been among the earliest and most successful cultivators of the grape under glass on the Hudson river. The border of his first grape-house, (which I understand was signally successful,) consisted entirely of leaf mould, or decayed vegetable matter. This house, however, has given place to a beautiful range; an engraving of which, together with the plan, is given in Vol. 1, No. 2, of the Horticulturist [See Fig. 12]. When I commenced the management of these houses, I anticipated difficulty in ripening such grapes as the Muscat of Alexandria, Flame-coloured tokay, Black Morocco, &c., being 100 miles north of New-York, but strange to say they have all ripened two weeks earlier than most of the houses on the Hudson. I can only account for this from the houses being protected at the north by a thick belt of woods, also from their being placed in a hollow or valley. Another good effect of this latter position, is that the glare of the glass roof is kept out of sight.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, April 24, 1847, letter to Robert Donaldson concerning the lawn at Blithewood (Anderson 1996: 180)[18] Back up to History

- “Do you know I have always felt that you do not sufficiently appreciate the beautiful shape and aspect of the Blithewood lawn. It and the unrivalled view are to my poor eye its crowning glories. Nothing therefore would give your place so much perfection and completeness as a very highly kept lawn. If I were you I should have a horse roller going after every shower & would mow regularly every fortnight. Try it one season & see if the beauty of the effect is not worth all the flowers in the world! There is a general opinion I know that a fine lawn is impossible in this country—but it is only an excuse for avoiding the small labour & expense attending it. Your neighbour Mrs. H. W. Livingston of the Upper Manor has proved this even upon her high & dry situation.”

- Anonymous, July 20, 1848, “Residence of S. Bigelow, Esq., Brighton, July 20th” (Magazine of Horticulture 14, 359–360)[19] Back up to History

- “The principal feature of the garden is a new and substantial greenhouse completed last year, upon the plan of one at Blithewood, on the North river, and it makes a very handsome structure, in excellent keeping, with a Gothic cottage or villa, but not harmonizing with the Grecian or Italian style. It is one hundred feet long, and divided into three compartments, the centre, twenty feet wide, being the greenhouse, and the two wings, forty feet each, the graperies.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, July 1848, “Hints to Rural Improvers” (Horticulturist 3, no. 1: 12)[20]

- “Among these places, those which enjoy the highest reputation, are Montgomery Place, the seat of Mrs. Edw’d Livingston, Blithewood, the seat of R. Donaldson, Esq., and Hyde Park, the seat of W. Langdon, Esq. The first is remarkable for its extent, for the wonderful variety of scenery—wood, water, and gardenesque—which it embraces, and for the excellent keeping of the grounds. The second is a fine illustration of great natural beauty—a mingling of the graceful and grand in scenery,—admirably treated and heightened by art. Hyde Park is almost too well known to need more than a passing notice. It is a noble site, greatly enhanced in interest lately, by the erection of a fine new mansion.”

- Bremer, Frederika, October 11, 1849, letter describing a visit to Blithewood, (Bremer 1853: 36–8)[21] Back up to History

- “After a sail of about three hours we reached Blithewood, the beautiful seat of the D.’s, whither we were invited to a great breakfast. . . .

- “. . . When, however, in the evening, I came forth into the open air, and, accompanied by the silent Mr. Downing, wandered quietly beside the glorious calm river, and contemplated the masses of light and soft velvet-like shadow, which lay on the majestic Katskill mountains, behind which the sun sank in cloudless splendour; then did the heart expand itself and breathe freely in that sublime and glorious landscape; then did I drink from the mountain-springs; then did I live for the first time that day. . . .

- “The following day. . . . In the afternoon I visited two or three beautiful places in the neighbourhood. On one of these, a point projecting into the river, has a ruin been built, in which ar placed various figures and fragments of walls and columns, which have been brought from the remarkable ruins lately discovered in Central America or Mexico. The countenances and the head-dresses resembled greatly those of Egyptian statues: I was struck in particular with a sphynx-like countenance, and a head similar to that of a priest of Isis. This ruin and its ornaments in the midst of a wild, romantic, rocky, and wooded promontory, was a design in the best taste.

- “In the evening we left this beautiful Blithewood, its handsome mistress and our friendly entertainers.”

- Elder, Walter, 1849, description of the gardener’s cottage at Blithewood (Elder 1849, 227)[22]

- “While in the service of Robert Donaldson Esq., we were the first to occupy that neat cottage, so widely known as the ‘gardener’s house at Blithewood,’ and so favourably noticed in Downing’s book on landscape gardening. There was an eighth of an acre of excellent ground attached to it; enclosed with a close board fence, and stocked with choice fruit trees, as a garden for us; and a good well and windlass for our private use, and also a neat hog pen. The cottage had three rooms, on the first floor, and two rooms above, and a fine cellar; the two upper rooms were then occupied by the pious and philanthropic Miss Isabella Donaldson, sister to our employer, as a Sunday School. All the youths of the neighbourhood assembled there on Sunday afternoons, and we were an assistant teacher.”

- Ehlers, Hans Jacob, April 1, 1852, letter to Thomas Barton of Montgomery Place disputing the taste and credibility of A. J. Downing (Ehlers 1852: 7–12)[23] Back up to History

- “On the first page of the last edition of his work on landscape gardening, is a picture of Blithwood [sic], the residence of Mr. Donaldson. This, I presume, is given to us as a specimen of the excellent taste of the author in landscape gardening. In examining this picture, a little experience will enable the observer to judge of the distance at which the picture was taken by the draughtsman. The minute manner in which the smallest particulars of the building are copied, make it evident that the distance could not have been more than twenty yards. You, sir, are acquainted with the original of this picture. You know the place called Blithwood; you can bear me witness when I assert that the mansion at Blithwood is no part of the landscape, for it is concealed by the trees which surround it. If the visitor at Blithwood wishes to obtain a view of the mansion, he must push his way through the mass of trees which conceal it, until he arrives within some twenty yards of the house itself. It is then visible, and he may, if he pleases, take a sketch of it. But what has such an object to do with the landscape, treated, as it has been, by the person who laid out the grounds, as if it were a privy, rather than the mansion of the proprietor, of which, the landscape which surrounds it, should be an ornamental adjunct.

- “Are we to regard such an arrangement as a specimen of excellent taste in landscape gardening? If we are, be pleased to show us where we are to look for this excellent taste? But we have not yet done with this picture of Blithwood. In the background of it are seen the Catskill mountains, and in the middle, the river with islands, &c. Now it happens that these objects are not visible from the point whence the dwelling house is taken. The draughtsman first drew the house with some of the trees around it, and was then compelled to alter his position, so as to get a view of the mountains, river, &c. But notwithstanding the different objects in the picture, in reality, represent views from different points, we have them all put down in the picture as if seen from one point. The picture is, therefore, an untrue one; it is false to nature. It may, indeed, furnish the clown the same sort of amusement which a piece of parti-colored calico, or a piece of speckled paper would a baby, but neither a landscape gardener, nor an amateur of the art, can look upon the scenery of Blithwood, as represented in that picture, as calculated to impress the mind with the charms of nature.

- “Let it not be said that these are mere assertions, for the proof of them is near at hand. You are a witness to their truth, and every man of sound sense and reason, may be the same.

- “There is another consideration which may not be without interest. It cannot be a matter of indifference to the landscape gardener, or the amateur of the art (it is for the latter class that Mr. Downing’s book is designed) from what point an object appears picturesque, or is shown to advantage. Blithwood might be very picturesque when seen from the moon, from the coal-shed, or from another little cabinet near the house. But the points of view ought at least to be accessible and decent. For, to what purpose is all the beauty created by the landscape gardener, if it can only be seen from points in the lawn or adjoining cornfields, where the observer is not permitted to tread, or must be sought near a coal-shed or cabinet-places which can only be approached with disgust? Now, the two or three points, from which the picture of Blithwood is taken, are not indeed situated in the moon, but they are near the places mentioned above. In truth, there are at Blithwood no points accessible and decent, from which a picturesque view can be obtained.

- “The sense of sight is the medium by which the mind becomes acquainted with the picturesque and all the forms of beauty in the material world. This sense of sight and an unbiassed judgment, are all that is needed. The objects to be seen are there—yonder is Blithwood, ten miles north of Barrytown, on the banks of the Hudson under the open vault of Heaven. It is easy of access, and he, who is seeking for the truth, may see all that has been described, and more—he will see walks resembling ditches, hardly fit for cattle to walk in, and other things in equally good taste. [. . . .]

- “I have made Blithwood alone the subject of my strictures, in my comments upon the taste of Mr. D. as a landscape gardener. It may, therefore, be supposed that I consider it the worst of all the places which are lauded in the works of Mr. D. Let me not be misunderstood. This is not the case; I have other reasons for the choice of Blithwood.

- “I am well aware that when the country seat of a gentleman is thus made the subject of remark, he may feel hurt and think that his feelings should have been spared. My excuse for the choice of Blithwood is this: In defending myself I was necessarily compelled to make a choice between many places, and should have considered myself inexcusable had I not made the choice with the view of causing as little pain as possible. In order to do this, I was compelled to look not so much to the place, as to the owner of it, for I had to take into consideration the ability of the latter to bear a little mortification. Who would put a heavy load on the back of an individual, whose strength was not known, while one is at hand whose powers of endurance were well ascertained?

- “I selected Blithwood for the following reasons: A few years ago I was engaged in laying out the grounds of a gentleman in the neighborhood of Blithwood. It was found necessary to drain the grounds by blind ditching. The owner of the estate chose to have the work done by his farmer. The result was that the work was insufficiently executed, the ditches having been made too shallow. I remonstrated against it from the beginning but in vain; no one would listen to me. In the following spring the insufficiency of the drainage was discovered when too late. Much labor and many trees were therefore lost. Although the facts of the case were universally known to the people living in the neighborhood, Mr. Donaldson nevertheless attributed the failure to me, and reported about that I did not know anything about draining and planting. He was contradicted by a gentleman, but still insisted upon the correctness of his statement. It is possible that Mr. Donaldson may have been ignorant of the facts above stated, but how could he dare to make such assertions without proof?

- “One such act indicated the possession of a degree of carelessness which will enable him to bear a little depreciation of his vaunted country-seat.

- “Some ten years since I introduced upon the estate of a gentleman in the neighborhood of Blithwood a machine for clearing walks and roads. A year afterwards Mr. Donaldson, having examined the machine, caused one to be made by the same blacksmith who made the former one after my drawing, and under my direction. The machine has been known and used in Europe many years. But strange enough we had at the time in Mr. Downing’s works, and since then in his book on Landscape-Gardening, an article on this same machine, in which Mr. Downing states that is was “invented by the ingenious Mr. Donaldson of Blithwood.” Although Mr. Donaldson has not yet invented gunpowder, we must not be surprised if we somewhere meet with the assertion that he has at last succeeded in inventing it. Mr. Downing may have been ignorant of the above mentioned facts, but how does he know that the machine was invented by the ingenious Mr. Donaldson? Above all, how could the latter bear this undeserved praise—a burden to an honest man heavier than undeserved blame. If he can support this with ease, need we fear that a little truth-telling respecting Blithwood will bear heavy on him?”

- Donaldson, Robert, 1853, “Importance of Water in Gardening” (Horticulturist 8: 128–130)[24] Back up to History

- “At a distance of 2,100 feet from the dwelling and gardens, there is a hill 60 feet high, adjoining one of the cataracts of the Sawkill—a stream which bounds the ornamental grounds. Upon this hill, which is level with the site of the house, I have erected a tower in the form of an Italian campanile, (see accompanying sketch,) which contains the reservoir, and serves also as a prospect tower. The head of water below the cataract is sufficient for driving hydraulic rams or forcing pumps to fill the reservoir to the top, 100 feet high and 300 feet distant.

- “To avoid interruption by frost in the use of an overshot water wheel and pump, I adopted two hydraulic rams (in case one should stop,) for constant use, which are covered up, and operate incessantly. The supply by rams is sufficient for all purposes but fountains and jets d’eau, which will require a forcing pump to be used in the summer. The water tower is 18 feet square and 45 feet high, placed upon a [[Terrace/Slope|terrace] for beauty and to gain elevation. Within this is a reservoir 7 feet square and 34 feet high, constructed in the strongest manner, of oak timber, and bolted with 1-inch iron, and planked and lined with lead,—resisting at the bottom a pressure of about 85,000 pounds. I was induced to accumulate the water in this expensive manner, to obtain great pressure in the pipes to prevent the gathering of sediment and air—to supply baths and water closets in the house, and jets d’eau and fountains in the garden and grounds.

- “From the bottom the water is conducted by 2-inch iron pipes, 3 ½ feet below the sod, and lateral pipes of lead, varying in size, to supply hydrants for root culture, irrigation, the cattle yard, stable the garden, the house and fountains. The water tower occupies a conspicuous position and is highly ornamental. The results are so satisfactory and beneficial, that I should recommend similar improvements wherever they can be made.”

- Smith, John Jay, 1856, “Visits to Country Places, No. 5” (Horticulturist 11: 547)[25] Back up to History

- “Annandale, some twenty miles above, and near Barrytown, was commemorated by Downing as Blithewood, then the seat of R. Donaldson, Esq., in his Landscape Gardening, with a lover’s praises. It is now the property of John Bard, Esq., who has changed its name to Annandale. Numerous improvements have been made by Mr. Bard and Mrs. Bard since they came into possession, and many others are in progress which must render it a very perfect example of all that is desirable in a country-seat. The river is four miles wide here, with islands interspersed,* and a full view of the Catskill Mountains on the opposite side, with their ever-varying shadows, sunshine, and clouds. Fine groups, and masses of trees and shrubbery, beautiful fountains, walks, drives, and, to this, hospitality and open-handed charity added, we give to Annandale the meed of extraordinary attraction and beauty.

- “The great water tower here, supplied from the noble brook between Mr. Bard’s and Montgomery Place, is admirably contrived.

- “Perhaps one of the most agreeable features at Annandale, is the great interest which the amiable proprietors take in the moral improvement of the neighborhood. With a noble and praiseworthy liberality, they have, we understand, established at their own expenditure, large and successful schools and churches, both upon the estate and at the neighboring village, where the whole expense of the erection of the buildings, the salaries of the clergymen and teachers, are defrayed from their private purse.

- “It is, we believe, the intention of Mr. Bard to erect a mansion of a size and dignity commensurate with the beauty of the place. Many persons with his ample means, would perhaps have done this at once, but he, with a forbearance beyond all praise, preferred to render unto God before rendering unto Caesar.

- “Annandale was planted by John C. Stevens, Esq., Admiral of the New York Yacht Club, who is still living; though is trees look old, he is not so, thus showing a successful instance of planting attaining perfection in the lifetime of a single individual. John C. Cruger bought it of Mr. Stevens.

- “Mr. Bard is erecting fine conservatories and forcing houses; he already possesses a stove, and other arrangements, for winter use. A new dwelling in every respect worthy this fine property of nearly two hundred acres, is to be constructed the ensuing season.

- “It was here that we remarked the fine groups of artistic Milan tables and chairs noticed on page 412.

- “*Upon the extreme point of one (Cruger’s Island), is a fine group of ruins brought from Palenque by the late John L. Stevens, and remarkably striking in their effect.”

Images

Alexander Jackson Davis, Map of Blithewood, c. 1840s.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Rustic Cottage at Blithewood, 1836.

Map

Other Resources

Bard College: Blithewood Garden

Blithewood Garden: Remember the Past

The Garden Conservancy: Blithewood Garden

Notes

- ↑ For the collaboration between Donaldson and Davis, see Jean Bradley Anderson, Carolinian on the Hudson: The Life of Robert Donaldson (Raleigh: Historic Preservation Foundation of North Carolina, 1996), 169.

- ↑ For the negotiations between Donaldson, Livingston, and John C. Cruger, who owned the Sawkill property, see Anderson 1996, 173–75.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Review of A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening,” The Gardener’s Magazine and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 7 (1841): 422.

- ↑ Reprinted in “Landscape Gardening,” The Cultivator: A Monthly Publication, Devoted to Agriculture 2, no. 3 (March 1845): 83.

- ↑ “Our Plate—Mr. Donaldson’s Farm,” The Cultivator: A Monthly Publication, Devoted to Agriculture 2, no. 8 (August 1845): 249. An earlier article published in the same journal also mentions Prince Albert. “The State Fair at Poughkeepsie,” The Cultivator: A Monthly Publication, Devoted to Agriculture 1, no. 10 (October 1844): 314. For an excerpt of the correspondence discussing this drawing, see Anderson 1996, 172.

- ↑ “Kaatskill, A Native Cow,” The New England Farmer 1, no. 1 (December 9, 1848): 3, view on Zotero. For Kaatskill’s 1844 prize at the New York State Agricultural Society exhibition in Poughkeepsie, see Franco̧is Guènon and John Stuart Skinner, A Treatise on Milch Cows, Whereby the Quality and Quantity of Milk Which Any Cow Will Give May Be Accurately Determined by Observing Natural Marks or External Indications Alone; the Length of Time She Will Continue to Give Milk, &c., 20th ed. (New York: McElrath, 1853), 7, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Geo. Kidd, “A Hint on Kitchen Gardens,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 10 (April 1849): 471–472, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Geo. Kidd, “Domestic Notices: Budding Roses,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 4, no. 5 (November 1849): 246, view on Zotero. At some point after his employment at Blithewood, Kidd left New York for Columbus, Georgia, where he continued to contribute short articles on gardening techniques to publications. Geo. Kidd, “Editor’s Table: Dear Sir,” The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 7 (1857): 390, view on Zotero; Geo. Kidd, “The Scuppernong,” The Plantation 1, no. 12 (April 9, 1870): 180, view on Zotero. It is not clear if he is the same George Kidd mentioned in relation to the London-based retirement charity known as the Gardeners’ Royal Benevolent Institution. G. Bond, “Gardeners’ Royal Benevolent Institution,” The Gardener’s Chronicle and Agricultural Gazette, no. 29 (July 21, 1855): 487, view on Zotero.

- ↑ This is the so-called Faneuil mansion, which Bigelow had purchased a decade earlier in 1839. John Perkins Cushing Winship, Historical Brighton: An Illustrated History of Brighton and Its Citizens, vol. 1 (Boston, MA: George A. Warren, 1899), 51, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Horace William Shaler Cleveland, “Foreign Notices: Notes from Our Foreign Correspondent,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 5 (November 1848): 244, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cruger had funded an expedition to the Yucatan peninsula led by John Lloyd Stephens, the Special Ambassador to Central America, and Frederick Catherwood, a prominent artist and architect who designed the greenhouse at the neighboring Montgomery Place. In exchange for his sponsorship, Cruger received a group of Mayan stone sculptures discovered in the ruins at Kabah and Uxmal, which he installed in his folly sometime after 1842. In 1919, Cruger’s daughter Cornelia sold the authentic Mayan sculptures to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Herbert J. Spinden, “The Stephens Sculptures from Yucatan,” Natural History: The Journal of the American Museum 20, no. 4 (1920): 381, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America; with a View to the Improvement of Country Residences. Comprising Historical Notices and General Principles of the Art, Directions for Laying out Grounds and Arranging Plantations, the Description and Cultivation of Hardy Trees, Decorative Accompaniments to the House and Grounds, the Formation of Pieces of Artificial Water, Flower Gardens, Etc.: With Remarks on Rural Architecture, 1st ed. (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1841), 23, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America; with a View to the Improvement of Country Residences. Comprising Historical Notices and General Principles of the Art, Directions for Laying out Grounds and Arranging Plantations, the Description and Cultivation of Hardy Trees, Decorative Accompaniments to the House and Grounds, the Formation of Pieces of Artificial Water, Flower Gardens, Etc.: With Remarks on Rural Architecture, 2nd ed. (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1844), 35, view on Zotero.

- ↑ “Our Plate—Mr. Donaldson’s Farm” 1845, 249, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. B. Allen, ed., “Farm and Villa of Mr. Donaldson,” American Agriculturist 5, no. 3 (March 1846): 88–90, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, “The New Vinery at Blithewood,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 1, no. 2 (August 1846): 57–58, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Geo. Kidd, “Culture of Foreign Grapes in Pots,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 5 (November 1848): 212–15, view on Zotero.

- ↑ As quoted in Anderson 1996, 180, view on Zotero.

- ↑ C. M. Hovey, ed., “Notes on Gardens and Nurseries. Residence of S. Bigelow, Esq., Brighton, July 20th,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 14 (August 1848): 359–60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, “Hints to Rural Improvers,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 1 (n.d.): 12, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederika Bremer, The Homes of the New World; Impressions of America, trans. Mary Howitt, vol. 1 (London: Arthur Hall, Virtue, & Co., 1853), 36–38, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter Elder, The Cottage Garden of America (Philadelphia, PA: Moss & Brother, 1849), 227, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hans Jacob Ehlers, Defence against Abuse and Slander, with Some Strictures on Mr. Downing’s Book on Landscape Gardening (New York. NY: Wm. C. Bryant & Co., 1852), 7–12, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Donaldson, “Importance of Water in Gardening,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 8 (1853): 128–30, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Jay Smith, “Visits to Country Places, No. 5,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 6 (1856): 547, view on Zotero.