Hannah Callender Sansom

Hannah Callender Sansom (November 16, 1737–March 9, 1801) was a Quaker woman from Philadelphia, who, between 1758 and 1788, kept a diary in which she describes country seats in Pennsylvania and New York as well as her family’s estates, Richmond Seat and Parlaville.

History

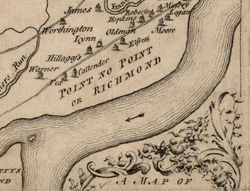

For over thirty years, between January 1758 and November 1788, Hannah Callender kept a diary in which she recorded, among many topics, descriptions of the country seats she visited, primarily in the vicinity of Philadelphia and New York. Callender, born in 1737, was the only child of William Callender Jr. (1703–1763) and Katharine Smith (1711–1789), devout Quakers and active members of the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting.[1] The family maintained a home on Front Street in Philadelphia as well as a plantation, Richmond Seat, which William established in Point-No-Point, about four miles north of Philadelphia on the banks of the Delaware River [Fig. 1].[2] Richmond Seat was a working plantation that produced “good English hay” for sale and, by 1752, boasted thirty-five acres of meadow with “good English grass,” an eight-acre orchard for the cultivation of various fruits, a two-acre garden, and “a small well-built brick house, with a boarded kitchen.”[3] With its agricultural focus and simple architecture, Richmond Seat fit well within Quaker ideals of plainness and frugality as well as the belief held by many Quakers during this period that farming in the country facilitated spiritual growth.[4]

As a member of a wealthy family, Callender was well educated and, according to the scholars Susan E. Klepp and Karin Wulf, had access to the collections of the Library Company of Philadelphia throughout her life. Both her father and her husband, Samuel Sansom Jr. (1738/39–1824), were members of the institution, which included various architectural, gardening, and horticultural manuals in its collections.[5] As part of their education, upper-class women in 18th-century Philadelphia were encouraged to read widely and to “enhance and display” the knowledge they acquired from books “through fieldwork and critical observation of the world around them.”[6] Visiting country houses provided “exclusive . . . educational opportunities” for Callender and her companions, who were often permitted to explore the estates’ art collections, architecture, and gardens.[7] After a September 1758 visit to James Hamilton’s Bush Hill, for example, Callender wrote about the “fine house and gardens, with Statues, and fine paintings,” and commented in particular upon works depicting St. Ignatius and the mythological story of the rape of Proserpine (). Hamilton had amassed one of the few notable fine art collections in the Philadelphia area during this period, and, because he often welcomed visitors, his estate served as “a kind of art museum for Philadelphia’s gentry.”[8]

From May to June 1759, twenty-one-year-old Hannah Callender traveled to New York City and Long Island. In her diary, she noted the “fine walk of locas [sic] trees” leading to the house at “Boyard’s [sic] Country seat” near New York, with “a beautiful wood off one side, and a Garden for both use and ornament on the other side.” Despite such praise, Callender championed Philadelphia’s gardens above New York’s, claiming that New York had “no gardens . . . that come up to ours of [P]hiladelphia” (view text). After returning to Philadelphia, Callender recorded the agricultural and ornamental uses of the land at Richmond Seat, observing that half of the sixty-acre property was covered in “a fine Woods,” an orchard, flower and kitchen gardens, and the house and barn, while the remaining thirty acres was given over to meadow (view text).

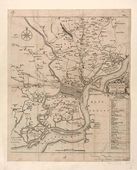

Hannah Callender’s diary also contains descriptions of various country houses situated along the banks of the Schuylkill River. In June 1762 she visited the estate of the late Tench Francis Sr. (d. 1758), and remarked upon the “fine prospect” available behind the house, from which she could see several neighboring estates, including Belmont, Dr. William Smith’s Octagon, and Baynton’s House, as well as “a genteel garden, with serpentine walks and low hedges.” From the garden, Callender observed, one could “descend by [slopes] to a Lawn” with a summer house and then descend again “to the edge of the hill which Terminates by a fen[c]e, for security” (view text). After a visit to Belmont, the country seat of William Peters, Callender described in great detail various features of the estate’s landscape design () [Fig. 2]. Belmont long remained one of Callender’s favorite sites. Twenty-three years after she first described the estate, she once again recorded her impression of Belmont, which was now under the purview of Richard Peters, lauding it as “the highest and finist [sic] situation I know, its gardens and walks are in the King William taste, but are very pleasant” ().

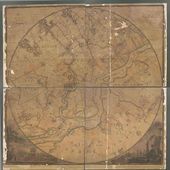

Hannah and her husband moved their primary residence from Philadelphia to Parlaville, a suburban retreat located about two and a half miles north of the city on the banks of the Schuylkill River, in July 1782 [Fig. 3].[9] As Klepp and Wulf have observed, Parlaville, in contrast to Richmond Seat, “was small, private, and quite deliberately divorced from commercial concerns.”[10] This contrast between Richmond Seat as a working plantation and Parlaville as a suburban retreat mirrors a larger generational shift in Quaker attitudes toward retiring to the countryside. According to Mark Reinberger and Elizabeth McLean, as the religious motivation for working the land waned, country houses were typically located closer to the city and primarily served as a “refuge . . . to protect and improve one’s physical and mental health, though with less emphasis on one’s spiritual health than in earlier days.”[11]

Joseph Francis was hired to plan the garden at Parlaville, and Hannah Callender evidently relished tending it, writing on one occasion that she “rose blythly to sow my seeds” and, in a separate entry, proclaiming gardening “the primitive occupation of man, designed by the almighty for a happy life!”[12] During the spring of 1785, Callender obtained a “variety of Trees, flowers, and plants” for Parlaville, including both native and non-native species. On April 24, for example, Callender noted that her husband and son Samuel “went nine miles up [the] Schuikill for white pine trees.” Four days later she procured “two Tuby Rose [tuberose] roots” that an acquaintance had brought from Barbados.[13] Hannah Callender and Samuel Sansom moved back to Philadelphia in July 1786, although they continued to maintain a secondary residence at Parlaville.[14]

Hannah Callender’s diary remained in the possession of her family after her death in 1801. In 1889, George Vaux, a descendant of Callender, published a selection of entries written by Callender between 1758 and 1762. The diary, which is now housed in the collection of the American Philosophical Society, was transcribed and published in full in 2010.[15]

—Lacey Baradel

Texts

- Sansom, Hannah Callender, September 9, 1758, diary entry describing Bush Hill, estate of James Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (2010: 67)[16] back up to History

- “. . . concluded upon a party to bush hill . . . in the afternoon, a fine house and gardens, with Statues, and fine paintings, particularly a picture of Saint Ignatius at his devotions, exceedingly well drawn, and the rape of Proserpine, where the grim god of hell, seems to exult with horrid joy, over his prey, who turns from him with a dread and loathing such as fully pictures, the horrors of a loathed embrace.”

- Sansom, Hannah Callender, June 11, 1759, diary entry describing Bayard’s country seat, near New York, NY (2010: 114)[16]

- “. . . took a walk to ---- Boyard’s Country seat, who was so complaisent as to ask us in his garden. the front of the house, faces the great road, about a quarter of a mile distance, a fine walk of locas trees now in full blossom perfumes the air, a beautiful wood off one side, and a Garden for both use and ornament on the other side from which you see the City at a great distance. good out houses at the back part. they have no gardens in or about New York that come up to ours of philadelphia”

- Sansom, Hannah Callender, June 23, 1759, diary entry describing the vicinity of New York, NY (2010: 117)[16]Callender 2010, view on Zotero.

- “. . . a good many pretty Country seats, In particular Murreys, a fine brick house, and the whole plantation in good order, we rode under the finest row of Button Wood I ever see . . .”

- Sansom, Hannah Callender, August 1, 1759, diary entry describing Richmond Seat, summer retreat of William Callender Jr. on the Delaware River in Point-No-Point near Philadelphia, PA (2010: 123)[16]Callender 2010, view on Zotero.

- “Morn: 8O'Clock Daddy and I went to Plantation . . . the place looks beautiful. the plat belonging to Daddy is 60 acres square: 30 of upland, 30 of meadow, which runs along the side of the river Delawar, half the uplands is a fine Woods, the other Orchard and Gardens, a little house in the midst of the Gardens, interspersed with fruit trees. the main Garden lies along the meadow, by 3 descents of Grass steps, you are led to the bottom, in a walk length way of the Garden, on one Side a fine cut hedge incloses from the meadow, the other, a high Green bank shaded with Spruce, the meadows and river lying open to the eye, looking to the house, covered with trees, honey scycle vines on the fences, low hedges to part the flower and kitchen Garden, a fine barn. Just at the side of the Wood, the trees a small space round it cleared from brush underneath, the whole a little romantic rural scene.”

- Sansom, Hannah Callender, August 30, 1761, diary entry describing the Moravian settlement at Bethlehem, PA (2010: 156)[16]Callender 2010, view on Zotero.

- “. . . Sister Garrison with good humour gave us girls leave, to step cross a field to a little Island belonging to the Single Bretheren, on it is a neat Summer house, with seats of turf, and button wood Trees round it.”

- Sansom, Hannah Callender, June 28, 1762, diary entry describing the estate of the late Tench Francis Sr. near Philadelphia, PA (2010: 180–81)[16]Callender 2010, view on Zotero.back up to History

- “..walked agreeably down to Skylkill along its banks adorned with Native beauty, interspersed by little dwelling houses at the feet of hills covered by trees, that you seem to look for enchantment they appear so suddenly before your eyes, on the entrance you find nothing but mere mortality, a spinning wheel, an earthen cup, a broken dish, a calabash and wooden platter: ascending a high Hill into the road by Robin Hood dell went to the Widow Frances’s place, she was there and behaved kindly, the House stands fine and high, the back is adorned by a fine prospect, Peter’s House, Smiths Octagon, Bayntons House &c and a genteel garden, with serpentine walks and low hedges, at the foot of the garden you desend by sclopes to a Lawn. in the middle stands a summer House, Honey Scykle &c, then you desend by Sclopes to the edge of the hill which Terminates by a fense, for security, being high & almost perpendicular except the craggs of rocks, and shrubs of trees, that diversify the Scene.”

- Sansom, Hannah Callender, June 30, 1762, diary entry describing Belmont, estate of William Peters, near Philadelphia, PA (2010: 182–83)[16]Callender 2010, view on Zotero. back up to History

- “. . . went to Will: Peters’s house, having some small aquaintance with his wife who was at home with her Daughter Polly. they received us kindly in one wing of the House, after a while we passed thro' a covered Passage to the large hall, well furnished, the top adorned with instruments of musick, coat of arms, crest, and other ornaments in Stucco, its sides by paintings and Statues in Bronze. from the Front of this hall you have a prospect bounded by the Jerseys, like a blueridge, and the Horison, a broad walk of english Cherre trys leads down to the river, the doors of the hous opening opposite admitt a prospect [of] the length of the garden thro' a broad gravel walk, to a large hansome summer house in a grean, from these Windows down a Wisto terminated by an Obelisk, on the right you enter a Labarynth of hedge and low ceder with spruce, in the middle stands a Statue of Apollo, note: in the garden are the Statues of Dianna, Fame & Mercury, with urns. we left the garden for a wood cut into Visto’s, in the midst a chinese temple, for a summer house, one avenue gives a fine prospect of the City, with a Spy glass you discern the houses distinct, Hospital, & another looks to the Oblisk.”

- Sansom, Hannah Callender, July 27, 1768, diary entry describing Edgely, estate of Joshua Howell, near Philadelphia, PA (2010: 232–33)[16]Callender 2010, view on Zotero.

- “. . . went to Edgeley. Joshua Howel has a fine Iregular Garden there, walked down to Shoolkill, after dinner . . . walked to the Summer House, in view of Skylkill when Benny [Shoemaker] Played on the flute.”

- Sansom, Hannah Callender, May 14, 1785, diary entry describing Bush Hill, estate of James Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (2010: 293)[16]Callender 2010, view on Zotero.

- “. . . to Hambleton’s Bush hill [estate,] walked over that good house, viewed the fine stucco work, and delightful prospects round. . .”

- Sansom, Hannah Callender, June 20, 1785, diary entry describing Belmont, estate of Richard Peters, near Philadelphia, PA (2010: 296)[16]Callender 2010, view on Zotero. back up to History

- “. . . crossed Brittains bridge, to John Penns elegant Villa, passed a Couple of delightfull hours, mounted our chaise and rode a long the Schuilkill to Peters place the highest and finist situation I know, its gardens and walks are in the King William taste, but are very pleasant, We had a very polite reception from Rich: Peters, his Wife, and mother, took to our chaise and by his direction, thro a pleasent rode to Riters ferry, crossed and continued our route along Schuilkill, to the falls tavern. . . .”

Images

Other Resources

Library of Congress Authority File

Notes

- ↑ William Callender Jr., emigrated from Barbados to America, arriving to the Delaware Valley in 1727. He married Katharine Smith of Burlington, New Jersey, in 1731, and they moved to Philadelphia in 1733. William Callender was a prosperous merchant, who earned his wealth in the West Indian sugar trade and through Philadelphia real estate investments. He also helped found the Library Company of Philadelphia and was involved in politics, serving in the Pennsylvania Assembly from 1753–56. Both William and Katharine with active members of Philadelphia’s Quaker community and played prominent roles in the Monthly Meetings. Hannah was their only child to survive infancy. George Vaux, “Extracts from the Diary of Hannah Callender,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 12, no. 4 (January 1889): 432, view on Zotero; Hannah Callender Sansom, The Diary of Hannah Callender Sansom: Sense and Sensibility in the Age of the American Revolution, ed. Susan E. Klepp and Karin Wulf (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010), 16–19, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Callender 2010, 17. By July 1760 William Callender had sold his Front Street house, and Richmond Seat became the family’s primary residence. Hannah Callender, diary entry for July 14, 1760, in Callender 2010, 138, view on Zotero.

- ↑ “Advertisements,” The Pennsylvania Gazette (February 16, 1744): 4, view on Zotero; “To Be SOLD,” The Pennsylvania Gazette (February 25, 1752): 2, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Mark Reinberger and Elizabeth McLean write that for Quaker men of William Callender’s generation, retreating to the countryside “was religious and involved . . . a closer contact with God through living in the country and farming.” Mark Reinberger and Elizabeth McLean, The Philadelphia Country House: Architecture and Landscape in Colonial Philadelphia (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015), 257, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Callender attended Anthony Benezet’s Society of Friends’ girls’ school in Philadelphia and also studied under Maria Jeanne Reynier, a French school mistress. In 1762 she married Samuel Sansom Jr., a merchant, real estate investor, and fellow Quaker from Philadelphia. Beginning in 1776, Samuel Sansom served as treasurer of the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Philadelphia Contributionship for the Insurance of Houses from Loss by Fire. The couple had five children: William (b. 1763), Sarah (b. 1764), Joseph (b. 1767), Catherine (b. 1769), and Samuel (b. 1773). Catherine died of smallpox as an infant, but all of the other Sansom children survived to adulthood. Callender 2010, 12, 14, 21, view on Zotero. The Library Company of Philadelphia’s 1770 and 1775 catalogues, for example, include titles such as William Halfpenny, Useful Architecture (London, 1752); The Builder’s Dictionary (London, 1734); James Lee, An Introduction to Botany (London, 1760); Thomas Hitt, A Treatise of Fruit Trees, 2nd ed. (London, 1757); Philip Miller, Gardener’s and Florist’s Dictionary (London, 1724); Philip Miller, The Gardener’s Kalendar, 12th ed. (London, 1760); John Hill, Eden: or, A Compleat Body of Gardening (London, 1757); (William) Salmon’s English Herbal (London, 1710); and James Wheeler, Botanist’s and Gardener’s Dictionary (London, 1765), among many others. Several of the library’s early printed catalogues are available online, http://librarycompany.org/about/history.htm.

- ↑ Sarah E. Fatherly, “‘The Sweet Recourse of Reason’: Elite Women’s Education in Colonial Philadelphia,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 128, no. 3 (July 2004): 230, 232, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fatherly 2004, 251, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Reinberger and McLean 2015, 240, view on Zotero.

- ↑ In the diary entry for July 4, 1785, Callender notes that “this day three years we come to live at Parlaville.” Callender 2010, 298, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Callender 2010, 167, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Reinberger and McLean 2015, 333, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hannah Callender, diary entries for December 10, 1784, and April 14 and 11, 1785, in Callender 2010, 282, 291, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hannah Callender, diary entries for April 12, 24, and 28, 1785, in Callender 2010, 291, 292, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hannah Callender, diary entry for January 1, 1788, in Callender 2010, 326, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Vaux 1889, view on Zotero; Callender 2010, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 16.8 16.9 Callender 2010, view on Zotero. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Callender 2010" defined multiple times with different content