Pot

History

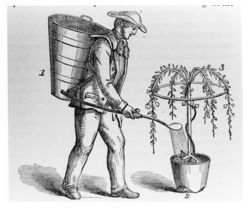

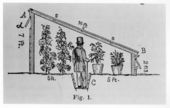

The plant or flower pot was a flat-bottomed, tubular container that was usually conical in profile, with little ornamentation [Fig. 1]. Pots contrasted with larger and more decorative or sculptural urns and vases also used to grow garden plants.[1] Flower pots, however, could be ornamented in subtle ways. For example, recent archaeological evidence reveals the use of “notched-rim” flower pots and flower pots with “neoclassical rouletting” at Monticello. At Williamsburg, Virginia, other forms have been found. These include a pot dated c. 1740 with a folded rim sloping downward, a later pot with a “triangular-sectioned rim and a cordon immediately below it,” another ornamented with “a shield of arms cast in relief and roughly similar to that of Queen Anne,” and another with “several winged cherubic faces.”[2] Rembrandt Peale’s 1801 portrait of his brother, Rubens, depicts an ornamented flower pot with a scored line and a braid just below its lip [Fig. 2]. Such attention to ornament sometimes extended to saucers that accompanied pots to collect water that drained from them.[3] The size, type, and decoration of such containers depended upon function and plant type, and descriptions of them abound in 19th-century treatises. J. C. Loudon's An Encyclopedia of Gardening (1826), for instance, included specifications for several types of pots, including those designed for the propagation of specialized plant types, such as aquatics.

Generally, pots were made of earthenware, clay-fired at low temperatures, and were covered with lead glaze or left unglazed. Occasionally, stoneware (coarse pottery made of clay that contained large amounts of silica, flint, and sand) and Chinese porcelain (translucent stoneware) were used. In 18th-century America, coarse earthenware (typically made from red clay) was chiefly produced in the Northeast. During the first half of the 19th century, the number of American manufacturers producing flower pots increased, as did the range of goods they produced. In the Northeast, potters were limited by coarser clays and continued working in the earthenware tradition. Further south, especially in places like New Jersey, Ohio, and Virginia, potters increasingly turned to stoneware in the production of flower pots, thus resulting in much regional variation.[4]

The use of glaze or paint was one point of disagreement. In 1834, seedsman Grant Thorburn, reflecting back upon his career, claimed that painting flower pots green attracted customers. British author George William Johnson underscored the usefulness of painting and glazing—both of which resulted in a glassy finish—because they helped seal in water and thus keep plant roots “more uniformly moist and warm.” On the other hand, English gardener Jane Loudon claimed that it was preferable to use porous material that allowed water to escape. Frequent treatise citations about glazed pots, however, suggest that glazed, painted, and other forms of decorated pots were quite important “embellishments,” to use A. J. Downing's term, for the garden.

Pots could be moved easily within a space or transferred from indoors to outdoors. William Hamilton, for example, occasionally rearranged his pots according to size in his green- or hothouse and, in good weather, moved them out to a nearby yard. In the painted views of Thomas Say’s garden in New Harmony, Indiana [Fig. 3], and of the Friends Almshouse in Philadelphia [Fig. 4], the artists depict potted plants scattered about the garden as decorative elements in the scene. In a letter to his son Rembrandt, Charles Willson Peale commended his botanist son Rubens for his display of pots around a basin and then painted them in his view of Belfield. At the Moreau House in Morrisville, Pennsylvania, as represented by Anne-Marguerite Hyde de Neuville in 1809, potted plants were used to ornament the barrier demarcating the drive to the house [Fig. 5]. The frequent use of pots in portraits and house views suggests they were an essential part of gardening, becoming emblematic in places where horticulture was seriously pursued. In contrast, vases and urns in gardens and views of gardens were associated with classical culture.

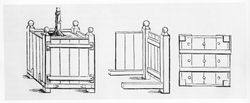

Pots were closely related to boxes or cases. Square containers, often made of wood, were used to house small shrubs and trees, such as oranges, laurels, or myrtles. Boxes, as opposed to pots, could accommodate larger plants and many illustrations of American gardens portray trees in such containers placed in front of structures like piazzas (as at George Washington’s Mount Vernon) and in the garden itself as in the view of Springland, William Russell Birch’s estate near Bristol, Pennsylvania [Fig. 6].

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Inventory of Arthur Allen III, 1728, describing the contents of Bacon’s Castle, home of Arthur Allen, Surry County, VA (quoted in Kelso and Most 1990: 25)[5]

- “2 flower potts and 2 watring potts.”

- Custis, John Parke, 1736, describing a request for flower pots made to Captain Friend (quoted in Hume 1974: 46)[6]

- “6 flower pots painted green to stand in a chimney to put flowers in the summer time with 2 handles to each pot for conveniency to lift up and down.”

- Hamilton, William, 1789, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Madsen 1988: A4 and A5)[7]

- “[May 2]. . . Hilton should [make] some mark immediately on the pot of each newly transplanted exotic, so as to prevent its being disturbed on my return. . . As soon as George has done the above all the exotics should be arranged according to their sizes in the way I directed particularly the pots on the shelves. . .

- “[June 2]. . .The pots should be put if possible in a warm situation screen’d from the noon day sun & gently waterd every two or three days. . . If George does as he ought no soul should be suffer’d alone in the pot & Tub enclosure.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, June 13, 1790, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (Jefferson 1944: 151)[8]

- “I enclose a few seeds of high-land rice which was gathered last autumn in the East Indies. . . I have sowed a few seeds in earthen pots. It is a most precious thing if we can save it.”

- Faris, William, 1795, describing his garden in Annapolis, MD (quoted in Sarudy 1989: 149)[9]

- “I moved the Potts into the seller for the Winter. . .”

- Peale, Charles Willson, September 14, 1814, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (quoted in Rudnytzky 1986: 38)[10]

- “Rubens has placed all his Pots round the fountain Bason and it makes a very handsome display the Bason being 13 feet long & 10 wide.”

- Thorburn, Grant, 1834, describing the painted flower pots sold in his shop in New York, NY (1834: 92–93)[11]

- “About this time the ladies in New York were beginning to shew their taste for flowers; and it was customary to sell the empty flower-pots in the grocery-stores; these articles also comprised part of my stock.

- “In the fall of the year, when the plants wanted shifting, preparatory to their being placed in the parlour, I was often asked for pots of a handsomer quality, or better make. As I stated above, I was looking round for some other means to support my family. All at once it came into my mind to take and paint some of my common flower-pots with green varnish paint, thinking it would better suit the taste of the ladies than the common brickbat coloured ones. I painted two pair, and exposed them in front of my window. . . They soon drew attention, and were sold. I painted six pair; they soon went the same way. Being thus encouraged, I continued painting and selling to good advantage: this was in the fall of 1802.”

- Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics Association, September 23, 1839, describing an exhibitor’s work in Portland, ME (quoted in Watkins 1950: 160)[12]

- “165. B. Dodge. Portland, Me. One Earthen Ware Flower Pot. Handsome model and good workmanship; covered with a superior green glaze. The Committee regret that the specimen is confined to this single article, but trust that before long more attention will be paid to this branch of American manufacture. A Diploma.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), October 1845, “Notes of a Visit to several Gardens in the Vicinity of Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York” (Magazine of Horticulture 12: 283)[13]

- “The Philadelphia potters now manufacture the largest sizes that are needed for plants. We saw here several two feet in diameter and of good proportion; they are far better than the unsightly boxes which are every where used, and we hope to see these pots introduced in their place; they can be obtained for about two and a half to three dollars each, and they are so well made that, with careful handling, they will last any length of time.”

Citations

- La Quintinie, Jean de, 1683, The Compleat Gard’ner (1683; repr., 1982: n.p.)[14]

- “To Pot, is to put or sow any Seed or Plant that is tender or curious into a Pot, for its better and safer Cultivation.”

- Dezallier d’Argenville, Antoine-Joseph, 1712, The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712: 77)[15]

- “CASES and Flower-pots serve likewise for the Embellishment of Gardens. In Cases, are raised Orange-Trees, Jasmins, Pomgranate-Trees, Myrtles, Lawrels, &c. which are regularly placed upon the Parterres of Orangery, . . . to form Walks between these, are put Pots and Vases of Dutch Ware, filled with Flowers of every Season, which are also set upon certain Forms made for that Purpose; or upon the Coping of the Walls of a Terrass, at a Descent of Steps; or else upon Plinths of Stone, in the Borders and Verges of Grass.”

- Cobbett, William, 1819, The American Gardener (1819: 56)[16]

- “107. The plants [in a green-house], of whatever sort or size, must be in what the English call pots, and what the Americans call jars.”

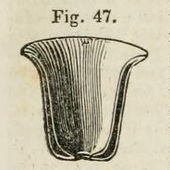

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 284–85)[17]

- “1407. Of flower-pots there are several species and many varieties.

- “The common flower-pot is a cylindrical tapering vessel of burnt clay, with a perforated bottom, and of which there are ten British sorts, distinguished by their sizes thus. . .

- “Common flower-pots are sold by the cast, and the price is generally the same for all the 10 sorts; two pots or a cast of No. 1, costing the same price as eight pots, or a cast of No. 11.

- “The store-pot is a broad flat-bottomed pot, used for striking cuttings or raising seedlings.

- “The pot for bulbous roots is narrower and deeper than usual.

- “The pot for aquatics should have no holes in the bottom or sides.

- “The pot for marsh-plants should have three or four small holes in the sides about one third of the depth from its bottom. This third being filled with gravel, and the remainder with soil, the imitation of a marsh will be attended with success.

- “The stone-ware pot may be of any of the above shapes, but being made of clay, mixed with powdered stone of a certain quality, is much more durable.

- “The glazed pot is chiefly used for ornament; they are generally glazed green, but, for superior occasions, are sculptured and painted, or incrusted, &c.

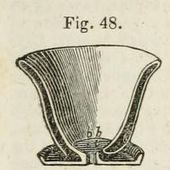

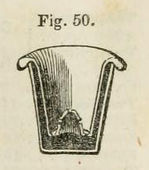

- “1408. The propagation-pot. . . has a slit in the side, from the rim to the hole in the bottom, the use of which is to admit a shoot of a tree for propagation by ringing in the Chinese manner. . .

- “The square pot is preferred by some for the three smallest sizes of pots, as containing more earth in a given surface of shelf or basis; but they are more expensive at first, less convenient for shifting, and, not admitting of such perfection of form as the circle, do not, in our opinion, merit adoption. They are used in different parts of Lombardy and at Paris.

- “The classic pot is the common material formed into vases, or particular shapes, for aloes and other plants which seldom require shifting, and which are destined to occupy particular spots in gardens or conservatories, or on the terraces and parapets of mansions in the summer season.

- “The Chinese pot is generally glazed, and wide in proportion to its depth; but some are widest below, with the saucer attached to the bottom of the pot, and the slits on the side of the pot for the exit or absorption of the water. Some ornamental Chinese pots are squared at top and bottom, and bellied out in the middle.

- “The French pot, instead of one hole in the centre of the bottom to admit water, has several small holes about one eighth of an inch in diameter, by which worms are excluded. . .

- “1412. The plant-box. . . is a substitute for a large pot; it is of a cubical figure, and generally formed of wood, though in some cases the frame is formed of cast-iron, and the sides of slates cut to fit, and move-able at pleasure. Such boxes are chiefly used for orange-trees.” [Fig. 7]

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[18]

- “POT, n. [Fr. pot; Arm. pod; Ir. pota; Sw. potta; Dan. potte; W. pot, a pot, and potel, a bottle; poten, a pudding, the paunch, something bulging; D. pot; a pot, a stake, a hoard; potten, to hoard.]

- “1. A vessel more deep than broad, made of earth, or iron or other metal, used for several domestic purposes; as an iron pot, for boiling meat or vegetables; a pot for holding liquors; a cup, as a pot of ale; and earthern pot for plants, called a flower pot, &c.”

- Loudon, Jane, 1845, Gardening for Ladies (1845: 211–12)[19]

- “FLOWER-POTS are commonly of a red porous kind of earthenware, which is much better for the plants than the more ornamental kinds sold in the china-shops: which from being glazed, and consequently not porous, are apt to retain the moisture so as to be injurious to the roots of the plants. . . Glazed pots are most suitable for plants kept in balconies, where they are much exposed to the air. . . There are ten sizes of pots in common use in British gardens, varying from two inches in diameter to a foot and a half. . . Besides these there are thumb-pots, about an inch in diameter and two inches deep, of which there are eighty to a cast; square stone pots for raising seeds, or striking cuttings, and which are seldom used but by nurserymen; and deep narrow pots for bulbous-rooted plants. Many other shapes have been invented to suit particular purposes, but the above are the only kinds in constant and regular use.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 228)[20]

- “FLOWER POTS are of various sizes and names. . .

- “The Philadelphia potters have long pursued the plan [whereby pots are classified according to their greatest diameter] proposed by Dr. Lindley, and those at distant points who may desire to order, have only to express the size in inches, i.e., the diameter at top.

- “The form and material also vary. Mr. Beck makes them very successfully of slate; and the prejudice against glazed pots is now exploded.

- “It was formerly considered important to have the pots made of a material as porous as possible; but a more miserable delusion never was handed down untested from one generation to another. Stoneware and chinaware are infinitely preferable, for they keep the roots more uniformly moist and warm. Common garden pots if not plunged, should be thickly painted.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849; repr., 1991: 422–23)[21]

- “There can be no reason why the smallest cottage, if its occupant be a person of taste, should not have a terrace decorated in a suitable manner. This is easily and cheaply effected by placing neat flower-pots on the parapet, or border and angles of the terrace, with suitable plants growing in them. For this purpose, the American or Century Aloe, a formal architectural-looking plants, is exceedingly well adapted, as it always preserves nearly the same appearance. Or in place of this, the Yuccas, or ‘Adam’s needle and thread,’ which have something of the same character, while they also produce beautiful heads of flowers, may be chosen. Yucca flaccida is a fine hardy species, which would look well in such a suitation. An aloe in a common flower pot is shown in Fig. 67; and a Yucca in an ornamental flower-pot in Fig. 68.” [Fig. 8]

- Anonymous, May 1851, “Garden Utensils [from The Gardener’s Magazine of Botany]” (Horticulturist 6: 216)

- “Fig. 2 represents a new pot constructed to prevent worms from entering at the bottom. in [sic] some gardens, where the earth is rich, the earth-worms are very troublesome, especially when the ground is damp. In these localities the worms crawl into the pots by means of the hole at the bottom, and if they commit little injury in the open ground, they are not so harmless among the roots confined in a pot. In order to obviate the evil arising from their intrusion, the new form of pot represented at figure 2, has been invented by M. Ghyselin, potter at Brussels. The bottom is distinguished by having three feet, which are only prolongations of the pot. The bottom is thus raised above the ground, and the worms are thereby prevented from entering at the hole. This pot has also the advantage of facilitating the circulation of air, and preventing the stagnation of water. [Worms, however, do not always enter garden-pots through the drainage hole, but sometimes, especially in small pots, from the top. Against this the proposed form offers no safeguard. After all, the best plan is to take care on what foundation the pots are set.]” [Fig. 9]

Images

Inscribed

J. C. Loudon, Plant boxes, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 285, figs. 177–79.

J. C. Loudon, “The propagation-pot” and “carnation-saucer,” in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, new ed. (1834), 540, figs. 444 and 445.

George William Johnson, Flowerpot with Trellis, in A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847), 601, fig. 169.

George William Johnson, The Manner in Which the Wire-trellis for Climbing Plants is Attached to Pots, in A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847), 602, fig. 170.

Anonymous, “An aloe in a common flower pot” and “A Yucca in an ornamental flower-pot,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 423, figs. 67 and 68.

Associated

Anonymous, Plan of the Harvard Botanic Garden, c. 1807. Harvard University Herbaria and the Botany Libraries, Cambridge, Mass.

Charles Willson Peale, View of the garden at Belfield, 1816.

Attributed

Mary Antrim, Brick House with Two Foreyards and Animals, 1807. Pots can been seen on either side of the cow and horse, as well as behind the fowl in the yard.

Anne-Marguerite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny Hyde de Neuville, The Moreau House, July 2, 1809.

Hugh Reinagle, Elgin Garden on Fifth Avenue, c. 1812.

Anne-Marguerite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny Hyde de Neuville, attr., Tomb du grande Washington au Mount Vernon, 1818. Pots are seen at top right between the arches.

Susanna Heebner, attr., House with Six-Bed Garden, 1818.

Thomas Birch, Point Breeze, c. 1820.

Anonymous, Section of a small, low-cost, wood frame “green-house,” Horticulturist 6, no. 1 (January 1851): 18, fig. 1.

Notes

- ↑ For more about the history of American pottery, see Lura Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1950), view on Zotero, which is still regarded as an authoritative volume. For a more general history, as well as a discussion of contemporary terminology relating to pottery, see Georgeanna H. Greer, American Stoneware: The Art and Craft of Utilitarian Potters (Exton, PA: Schiffer, 1981), view on Zotero. For recent writings in material culture pertaining to pottery, see, for example, George L. Miller and Ann Smart Martin, “English Ceramics in America,” in Decorative Arts and Household Furnishings in American, 1650–1920, ed. Kenneth L. Ames and Gerald W. R. Ward (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1989), view on Zotero, and Winterthur Portfolio 19 (Spring 1984). For additional information on American ceramics, see Susan R. Strong, History of American Ceramics: An Annotated Bibliography (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 1983), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William M. Kelso, “Landscape Archaeology and Garden History Research: Success and Promise at Bacon’s Castle, Monticello, and Poplar Forest, Virginia,” in Garden History: Issues, Approaches, Methods, ed. John Dixon Hunt (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1992), 51, view on Zotero. See also Audrey Noël Hume, “Flowerpots and Urns,” in Archaeology and the Colonial Gardener (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1974), 39–61, view on Zotero.

- ↑ At the c. 1680 garden at Bacon Castle, “coarseware flowerpots and decorated saucer rims” have been uncovered. See Nicholas Luccketti, “Archaeological Excavations at Bacon’s Castle, Surry County, Virginia,” in Earth Patterns, Essays in Landscape Archaeology, ed. William M. Kelso and Rachel Most (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 1990), 38, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ann Smart Martin and George Miller to Elizabeth Kryder-Reid and Anne L. Helmreich, August 5, 1996.

- ↑ William M. Kelso and Rachel Most, eds., Earth Patterns: Essays in Landscape Archaeology (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1990), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Audrey Noël Hume, “Flowerpots and Urns,” in Archaeology and the Colonial Gardener, Colonial Williamsburg Archaeological Series 7 (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg, 1974), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Karen Madsen, “William Hamilton’s Woodlands,” (paper presented for seminar in American Landscape, 1790–1900, instructed by E. McPeck, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Barbara Wells Sarudy, “Eighteenth-Century Gardens of the Chesapeake,” Journal of Garden History 9 (1989): 104–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kateryna A. Rudnytzky, “The Union of Landscape and Art: Peale’s Garden at Belfield” (Honors thesis, LaSalle University, 1986), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Grant Thorburn, Forty Years’ Residence in America, or The Doctrine of a Particular Province Exemplified in the Life of Grant Thorburn, the Original Lawrie Todd, Seedsman, New York (London: J. Fraser, 1834), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Watkins 1950, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes of a Visit to Several Gardens in the Vicinity of Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, in October, 1845,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 12, no. 8 (August 1846): 241–48, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jean de La Quintinie, The Compleat Gard’ner, or Directions for Cultivating and Right Ordering of Fruit-Gardens and Kitchen Gardens, trans. John Evelyn (1683; repr., New York: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A.-J. (Antoine Joseph), Dézallier d’Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening; Wherein Is Fully Handled All That Relates to Fine Gardens, . . . Containing Divers Plans, and General Dispositions of Gardens. . . , trans. John James (London: Geo. James, 1712), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Cobbett, The American Gardener (Claremont, NH: Manufacturing Company, 1819), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden, ed. A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.