Elgin Botanic Garden

The Elgin Botanic Garden, established in 1801 in New York City by Dr. David Hosack (1769–1835), was a systematic arrangement of plants for scientific and pedagogical purposes. It served as a garden for teaching botany and materia medica at both the medical school of Columbia College and the College of Physicians and Surgeons. It was located in the area that is now midtown Manhattan.

Overview

Alternate Names: Botanic Garden of the State of New York

Site Dates: 1801–1811

Site Owner(s): David Hosack (1769–1835); The State of New York; The College of Physicians and Surgeons; Columbia College

Associated People: Andrew Gentle (gardener); Frederick Pursh (1774–1820, gardener); Michael Dennison (seedsman)

Location:: New York, NY

Condition: demolished

History

While serving as professor of botany at Columbia College, Samuel Latham Mitchill proposed the development of a botanic garden in New York City to be administered either by the College or by New York’s Society for the Promotion of Agriculture, Arts and Manufactures. As Mitchill explained in a report to the Society in 1794, a garden comprised of indigenous and imported plants would be “one of the genteelest and most beautiful of public improvements,” while also providing essential aid in the teaching of botany and the conducting of agricultural experiments ().[1] Mitchill’s proposal reflects his medical education at the University of Edinburgh, where botanic gardens served as essential adjuncts to courses in botany and materia medica.[2] Although nothing came of his plan, the idea was revived by his successor, David Hosack, another Edinburgh-educated physician, who was appointed professor of botany at Columbia in May 1795, and professor of materia medica two years later. In November 1797 Hosack informed the trustees of Columbia College that even his “large and very extensive collection of coloured [botanical] engravings” fell short of the pedagogic utility that a botanic garden would provide. He therefore requested that “the professorship of botany and materia medica be endowed with a certain annual salary to defray the necessary expenses of a small garden, in which the professor may cultivate, under his immediate notice, such plants as furnish the most valuable medicines, and are most necessary for medical instruction” (view text). Despite agreeing with Hosack in principle, the trustees provided no funds. He next directed his request to the state legislature, but his letter of February 1800 requesting an annual stipend of £300 met with equally disappointing results.[3]

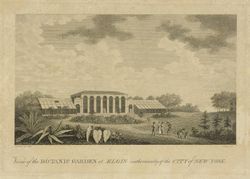

Finally, in 1801, Hosack resolved to take the matter into his own hands, personally financing the purchase of twenty acres of land in the countryside to the north of the city, between what is now 47th and 51st Streets and Fifth and Sixth Avenues (an area that now includes Rockefeller Center) [Fig. 1].[4] Columbia College was then located four miles to the south in lower Manhattan, a distance that limited the garden’s practicality from the outset. In other respects, however, the situation was ideal. Hosack noted that “the view from the most elevated part, is variegated and extensive, and the soil itself of that diversified nature, as to be particularly well adapted to the cultivation of a great variety of vegetable productions” (view text). He named the garden “Elgin” after his father’s birthplace in Scotland. Soon after purchasing the property, he wrote to “friends in Europe and in the East and West Indies [asking] for their plants.”[5] In July 1803, while his collection was “yet small,” he made a similar request of the Philadelphia physician Thomas Parke, asking for his help in obtaining duplicate specimens of “rare and valuable plants” owned by their mutual friend William Hamilton, as well as medicinal plants and a catalog from the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (view text). Dr. Parke had already provided Hosack with plans of the elaborate greenhouse with flanking hothouses that Hamilton built ten years earlier at The Woodlands.[6] Hosack adopted roughly the same design and dimensions for the Elgin greenhouse complex, which he described as “constructed with great architectural taste and elegance” (). After completing the central block in 1803, Hosack added the hothouses in 1806 and 1807. The artist John Trumbull documented the buildings in a drawing made in June 1806 [Fig. 2], probably as a study for the background of his portrait of Hosack, presently known only through a related engraving [Fig. 3].

Hosack reportedly had “in cultivation at the commencement of 1805, nearly fifteen hundred American plants, besides a considerable number of rare and valuable exotics” (view text). The following year, when he published the first catalog of the garden, the number of plants had grown to nearly 2,000 species, with the “the greater part of [the twenty acres] . . . now in cultivation” (view text). While continuing to collect plants with the aid of well-connected friends such as Thomas Jefferson (view text), Hosack turned his attention to laying out the grounds, ensuring that they were not only “arranged and planted agreeably to the most approved stile of ornamental gardening,” but also according to scientific taxonomies and the conditions of climate and terrain best suited to each plant.[7] By 1810 when he published his Description of the Elgin Garden, Hosack had carried out the plan outlined in his 1806 Catalogue of encircling the garden with a “belt of forest trees and shrubs, native and exotic.” This “judiciously chequered and mingled” collection was comprised of “the oak, the plane, the elm, the sugar maple, the locust, the horse chesnut, the mountain ash, the basket willow, and various species of poplar.” In front of these trees a “similarly varied collection” of native and foreign shrubs was laid out in the form of an amphitheatre, “which, winding with the walks, presents at every step something new and engaging.” On the opposite side of the garden, “the eye reposes on the green lawn which is occasionally intercepted with groups of trees and shrubs happily adapted to its varied surface.” Walks on either side of the garden led to compartments of plants laid out according to their scientific order, and beyond them lay a nursery of fruit trees, a pond “devoted to the varieties of nymphoea, pontederia and other aquatics,” and native plants, such as rhododendron, magnolias, and willows, which favored the moist ground adjacent to the pond. At higher elevations, rocky outcroppings were planted with “varied species of pine, juniper, yew, and hemlock.” In the vicinity of the greenhouse and hothouses were shrubs arranged in clumps and borders containing flowering plants. Throughout the garden, every tree, shrub, and plant bore a label with its botanic name “for the instruction of the student.” The entire garden was enclosed by a stone wall, seven feet high and two and-a-half feet thick (view text).[8]

Following his appointment in 1808 as professor of natural history at New York’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, Samuel Latham Mitchill conducted open-air classes at the Elgin Botanic Garden. An unidentified student who made multiple visits to the garden in 1810 reported that Mitchell was assisted by “two promising young botanists”: James Inderwick (c. 1788–1815), a Columbia graduate who had stayed on to take anatomy and chemistry classes at the medical school in 1808–9, and Hosack’s nephew, Caspar Wistar Eddy (1790–1828), who in 1807, while still a medical student at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, had created an herbarium and published a catalogue, Plantae Plandomenses, documenting plants indigenous to Mitchill’s 230-acre Long Island estate.[9] According to the student, Eddy was responsible for “demonstrating the marks peculiar to the species,” while Inderwick “expound[ed] the characters which distinguish the genus” (view text). After receiving his M.D. from the College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1811, Eddy himself began conducting lectures on botany at the Elgin Botanic Garden in May 1812 (view text).

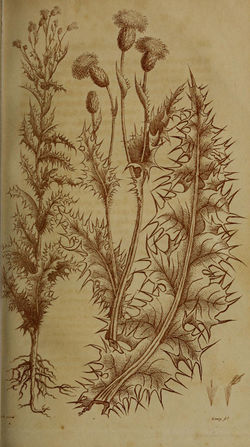

Inderwick was involved in Hosack's plan to scientifically document the plants at Elgin in “AMERICAN BOTANY, or a ‘Flora of the United States,’” a publication Hosack intended to publish, he announced in 1811, as soon as he had secured the garden’s permanent maintenance (view text). Modeled on John Edward Smith’s monumental English Botany (36 vols., 1790–1814), Hosack’s flora was to include drawings by Inderwick, whom he had already employed to illustrate articles published in the American Medical and Philosophical Register, the journal that he and the New York physician John Wakefield Francis (1789–1861) edited jointly from 1810 to 1814.[10] Although most of Inderwick’s drawings for the journal represented anatomical subjects, his illustration of the Canada Thistle (Cnicus Arvensis) [Fig. 4] for an article Hosack published in October 1810 indicates the kind of images he might have produced for Hosack’s American Botany, had that project ever advanced beyond the planning stage.[11] According to Hosack, additional drawings for American Botany would be provided by another Columbia graduate, John Eatton Le Conte (1784–1860), who was probably then working on the catalogue of plants indigenous to New York City that he would publish (with a dedication to Hosack) in the American Medical and Philosophical Register in October 1811.[12] Le Conte collected many plants for the garden while visiting his family’s plantation, Woodmanston, in Georgia, and he went on to a distinguished natural history career, producing botanical illustrations that justify Hosack’s early endorsement [Fig. 5].[13]

The laboring figures represented in an oil painting of about 1810 hint at the numerous farmers and gardeners Hosack employed over many years to cultivate, plant, and maintain the Elgin garden.[14] [Fig. 6] The Scottish nursery- and seedsman Andrew Gentle claimed to have “commenced operations for Dr. Hosack, in New-York, by laying out his grounds” in 1805, and he remained at the garden for the next few years.[15] In 1809, on the recommendation of Bernard M’Mahon (view text), Hosack hired as gardener the German botanist Frederick Pursh, who had previously visited “the houses of the Botanick garden at New York” on October 3, 1807, while passing through the city on his way to Philadelphia.[16] According to Hosack, Pursh made “very numerous contributions . . . during the period he had charge” of the garden, but by the close of 1810 he had been replaced by Michael Dennison, an English seedsman recommended by Lee and Kennedy, a well-known firm of nurserymen in Hammersmith, London (view text). Although Hosack expected Pursh to continue his association with Elgin in the capacity of “a very industrious and skilful botanist to collect from different parts of the union such plants as have not yet been assembled at the Botanic Garden,” Pursh left America for England toward the end of 1811.

The high cost of maintaining the Elgin Botanic Garden soon swamped David Hosack's financial resources. He had expected public support to be forthcoming once the garden’s utility had been demonstrated, but his efforts to secure loans from the New York state legislature in 1805 and 1806 came to nothing, despite the governor’s support (view text).[17] Moreover, the market in fruits, vegetables, medicinal herbs, and hothouse plants—operated at the garden by Andrew Gentle (view text)—failed to raise sufficient funds to offset the high cost of labor. In 1808 Hosack concluded that selling the garden was the only means of preserving it. Following considerable delay, the New York state legislature agreed to the purchase on January 3, 1811, with the provision that responsibility for the garden’s management would be delegated to the College of Physicians and Surgeons.[18] The College lacked funds to maintain the garden, however, and it soon fell into disrepair. On a visit in August 1813 Hosack, who continued to collect seeds and plant materials for the garden, was distressed to find that the greenhouse plants had not been set outdoors during the summer, that many of them were missing, that the shrubbery in front of the greenhouse was choked with sunflowers, and that vegetation had overtaken the walks.[19]

The garden’s condition continued to decline following the transfer of ownership to Columbia College in 1814. Two years later, Hosack complained to one of the College’s trustees that the gardener, Michael Dennison, was “removing everything valuable from the collection.”[20] From early 1817 to 1823 Andrew Gentle returned to Elgin, granted a year-to-year lease free of charge in exchange for maintaining the greenhouse and grounds. In May 1819 the greenhouse plants along with “ornamental trees” and shrubs were transferred to the New York Hospital. Despite several attempts by Hosack to transfer care of the garden to an institution that could provide more attentive oversight, Columbia preferred to retain control, renting the property to a variety of tenants, including the seedsman David Barnett from 1825 to 1835.[21] The rapid growth of New York City meant that by the late 1850s the garden was situated well within the urban hub, rather than on its outskirts. The value of the property had risen accordingly, from several thousand dollars to tens of millions. Columbia ultimately divided the land into numerous lots, which it sold or leased at high prices, generating the financial capital that allowed the college to expand into a world-class university.[22]

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Mitchill, Samuel Latham, 1794, report to the Society for the Promotion of Agriculture, Arts and Manufactures in the State of New York (1792: xxxix–xlv)[23] back up to History

- “The establishment of a Garden is nearly connected with the Professorship of Botany under the College, and the Lectures on that branch must be always very lame and defective without one. . . . A Botanic Garden is not only one of the genteelest and most beautiful [Hosack changed to: most useful and most important] of public improvements; but it also comprises within a small compass the History of the Vegetable Species of our own Country; and by the introduction of Exotics, makes us acquainted with the plants of the most distant parts of the earth. Likewise, by facilitating experiments upon plants at this time, when a true Theory of Nutrition and Manures is such an interesting desideratum, a Botanic Garden may be considered as one of the means of affording substantial help to the labours of the Agricultural Society, and be conducive to the improvement of modern husbandry. When these things are duly considered, it can scarcely be doubted, that a Botanic Garden, under the direction of the Society, or of the College, with a view to further the agricultural interest, will be set on foot and supported by legislative provision; to the end that young minds be early imbued with proper ideas on this important subject.”

- Hosack, David, November 1797, memorial presented to the President and Members of the Board of Trustees of Columbia College (1811: 7–8)[24] back up to History

- “It has been to me a source of great regret that the want of a Botanical Garden, and an extensive Botanical Library, have prevented that advancement in the interests of the institution which might reasonably have been expected.

- “ . . . To this end, I have purchased for the use of my pupils such of the most esteemed authors as are most essential in teaching the principles of Botany; and at a considerable expense I have been enabled to procure a large and very extensive collection of coloured engravings; but the difficulty of teaching any branch of natural philosophy, and of philosophy, and of rendering it interesting to the pupil, without a view and examination of the objects of which it treats, will readily be perceived: it will also occur to you that books, or engravings, however valuable and necessary, are of themselves insufficient for the purposes of regular instruction in medicine.

- “The obvious and only effectual remedy would be the establishment of a Botanical Garden: this would invite a spirit of inquiry. The indigenous plants of our country would be investigated, and ultimately would promise important benefits, both to agriculture and medicine. . . . I beg leave to suggest . . . that the professorship of botany and material medica be endowed with a certain annual salary, sufficient to defray the necessary expenses of a small garden, in which the professor may cultivate, under his immediate notice, such plants as furnish the most valuable medicines, and are most necessary for medical instruction.”

- Michaux, François André, 1802, Travels to the West of the Alleghany Mountains (1802: 14)[25]

- “During my stay at New York I frequently had an opportunity of seeing Dr. Hosack, who was held in the highest reputation as a professor of botany. He was at that time employed in establishing a botanical garden, where he intended giving a regular course of lectures. This garden is a few miles from the town: the spot of ground is well adapted, especially for plants that require a peculiar aspect of situation.”

- Hosack, David, July 25, 1803, letter to Dr. Thomas Parke, regarding the greenhouses at Elgin and The Woodlands (quoted in Long 1991: 144)[26]back up to History

- “I duly received the plans of Mr. Hamiltons green and hot houses. My greenhouse [exclusive of the hothouses] is now finishing—it will not differ very individually from Mr. Hamiltons. It is 62 feet long 23 deep—and 20 high in the clear. . . . I shall heat it by flues, they will run under the stays so they will not be seen—my walks will be spacious . . . hot houses are for next summer’s operation. My collection of plants is yet small. I have written to my friends in Europe and in the East and West Indies for their plants. I will also collect the native productions of North and South America. What medical plants can Mr. Bartram supply—request him to send me a catalogue. . . . I hope William Hamilton will have duplicates of rare and valuable plants—I will supply him anything I possess.”

- Hosack, David, autumn 1806, preface to A Catalogue of Plants Contained in the Botanic Garden at Elgin (1806: 3–7)[27]

- “The establishment of a Botanic Garden in the United States, as a repository of native plants, and as subservient to medicine, agriculture, and the arts, is doubtless an object of great importance. . . .

- “In the year 1801 I purchased, of the Corporation of the city of New-York, twenty acres of ground; the greater part of which is now in cultivation. Since that time, a Conservatory, for the more hardy green-house plants, has been built; in addition to which, two Hot-Houses are now erecting for the preservation of those plants which require a greater degree of heat.

- “The grounds will be arranged in a manner the best adapted to the different kinds of plants, and the whole enclosed by a belt of forest trees and shrubs, native and exotic.

- “A primary object of attention in this establishment will be to collect and cultivate the native plants of this country, especially such as possess medicinal properties, or are otherwise useful. . . .

- “I must acknowledge the obligations I am under to many gentlemen who have already befriended this establishment, especially to my most esteemed instructor and friend Dr. James Edward Smith, the President of the Linnaean Society of London; to Professor [Martin] Vahl, and Mr. [Niels] Hoffman Bang, of Copenhagen; to Professor [René Louiche] Desfontaines and [André] Thouin, of the Botanic Garden of Paris; to Mr. Alderman [George] Hibbert, and Dr. [John Coakley] Lettsom of London; Mr. [Richard Anthony] Salisbury, proprietor of the Botanic Garden of Brompton; Dr. [Giovanni Valentino Mattia] Fabroni, Director of the Royal Museum at Florence; and Mr. Andrew Michaux, author of the Flora Boreali Americana, &c. &c. From these gentlemen I have received many valuable plants, seeds, and botanical works, accompanied with the most polite offers of their further contributions to this institution.”

- Lewis, Morgan, governor of New York, January 28, 1806 (Hosack 1811: 12)[24] back up to History

- “Application was made to the legislature at their last session, by a gentleman of the city of New-York, for aid in the support of a Botanic Garden, which he had recently established. At the request of some of the members, I, in the course of last summer, paid it two visits, and am so satisfied with the plan and arrangement, that I cannot but believe, if not permitted to languish, it will be productive of great general utility. The objects of the proprietor are, a collection of the indigenous, and the introduction of exotic plants, shrubs &c. and by an intercourse with similar establishments, which are arising in the eastern and southern states, to insure the useful and ornamental products of southern to northern, and of northern to southern climes. In the article of grasses, I was pleased to see a collection of one hundred and fifty different kinds. A portion of ground is allotted to agricultural experiments, which cannot but be beneficial to an agricultural people. When it is considered that this branch of natural history embraces all the individuals of the vegetable which afford subsistence to the animal world, compose a large portion of the medicines used in the practice of physic, and mam of the ingredients essential to the useful arts, its utility and importance is not to be questioned. But in a country young as ours, the experimental sciences cannot be expected to arrive at any degree of excellence without the patronage and bounty of government; for individual fortune is not adequate to the task.”

- Hosack, David, September 10, 1806, letter to Thomas Jefferson[28] back up to History

- “Knowing your attachment to science and the interest you feel on the progress of it in the united states, I take the liberty of enclosing to you a Catalogue of plants [in the Elgin Botanic Garden] which I have been enabled to collect as the beginning of a Botanic garden—

- “you will readily perceive that my intention in this little publication is merely to announce the nature of the Institution and to facilitate my correspondence with Botanists as they will hereby know what plants will be accepteble to me and what they may expect in return—in two or three years when my collection may be more extensive I propose to publish it in a different shape arranging the plants under different heads viz Medicinal—Poisonous—those useful in the arts—in agriculture &c with notes relative to their use and culture accompanied with engravings of such as may be either entirely new or are not well figured in books—

- “I feel much interested in the result of the enquiries instituted by you relative to the Missouri—Black River &c. In Natural History much is also to be expected from exploring the territory in the course of Red River—that latitude is always rich in vegetable productions—if it should be contemplated to explore that or any other part of our country, there is now a gentleman in this state who might be induced to undertake it and whose talents abundantly qualify him for an employment of this sort, the person I refer to is Mr [André] Michaux the editor of the Flora Boreali America—he being at present in New York I take the liberty of mentioning his name to you—under your auspices Sir establishments of this nature may be encouraged:—it has occurred to me that much also might be done in exploring the native productions of the united states if the Government were to appropriate to every Botanic garden a small sum—for the express purpose of employing a suitable person to investigate the vegetable productions growing in its neighbourhood—an annual appropriation of this sort allotted to the Botanic gardens of Boston—New York—Virginia and South Carolina would in a short time be productive of great good—

- “Another object which will claim much of my attention will be to naturalize as far as possible to our climates the productions of the southern states and of the tropics—I believe much may be done upon this subject—four years since I planted some cotton seed, late in the spring—it grows to the usual size to which it attains in the southern states and ripened its seed before October—Those seeds were planted and succeeded equally well the second year—John Stevens Esq of Hoboken New Jersey has also succeeded in the same experiment and at this time has a considerable quantity of cotton ripening its seed, the growth from seeds raised by him the last year, it is also to be remarked that this summer has been unusually cool—I conceive it therefore not improbable that Virginia and Maryland if not Pennsylvania and New york—might cultivate this plant to advantage—the short staple doubtless would succeed—

- “If . . . the gentlemen who are at present on their travels to the Missouri, discover any new or useful plants I should be very happy in obtaining a small quantity of the seeds they may procure.”

- Gentle, Andrew, June 4, 1807, Notice concerning the Elgin Botanic Garden, published in the New York Commercial Advertiser (Stokes 1926: 5:1460–61)[29] back up to History

- “As it was the original design in forming this establishment to render it not only useful as a source of instruction to the students of medicine but beneficial to the public by the cultivation of those plants useful in diseases, by the introduction of foreign grasses, and by the cultivation of the best vegetables for the table; our citizens are now informed that they can be supplied with medicinal Herbs and Plants, and a large assortment of green and Hot House Plants etc.”

- Bard, Samuel, November 14, 1809, address delivered to the Medical Society of Dutchess County (Hosack 1811: 30)[24]

- “Convinced as I am of the great and general importance of correct medical instruction, and anxious that our schools should be fostered by necessary patronage, I cannot but regret the failure of the proposal made last year in our legislature, for the purchase of Dr. Hosack’s botanic garden. It would be too tedious at present to point out how much medicine may be benefitted, how greatly the arts may be enriched, and hor many of the comforts, the pleasures, and even the necessaries of life may be improved by such an institution. . . .

- “By the purchase of the botanic garden, a national ornament and most useful establishment, already brought to a great degree of perfection, will be preserved: by which our medicine, our agriculture and our arts, the elegancies, and the conveniences of life will necessarily be improved.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard to Thomas Jefferson, December 24, 1809 (Jefferson 2005: 2:89–91)[30] back up to History

- “On Governor Lewis’s departure from here, for the seat of his Government, he requested me to employ Mr Frederick Pursh, on his return from a collecting excurtion he was then about to undertake for Doctor Barton, to describe and make drawings of such of his collection as would appear to be new plants, and that himself would return to Philadelphia in the month of May following. About the first of the ensuing Novr Mr Pursh returned, took up his abode with me, began the work, progressed as far as he could without further explanation, in some cases, from Mr Lewis, and was detained by me, in expectation of Mr Lewis’s arriv[al] at my expence, without the least expectation of any future remuneration, from that time till April last; when n[ot] having received any reply to several letters I had wri[tten] from time to time, to Govr Lewis on the subject, nor being able to obtain any in[dication?] when he probably might be expected here; I thought it a folly to keep Pursh longer idle, and recommended him as Gardener to Doctor Hosack of New York, with whom he has since lived.

- “The original specimens are all in my hands, but Mr Pursh, had taken his drawings and descriptions with him, and will, no doubt, on the delivery of them expect a reasonable compensation for his trouble.”

- Newton, Joseph, Arthur Smith, John F. West, Timothy B. Crane, January 16, 1810, Estimate of the Buildings at the Elgin Botanic Garden (Hosack 1811: 45)[24]

- “We, the subscribers, builders, and residents of the city of New-York, at the request of doctor David Hosack, have valued the improvements on his land, near the four mile stone, called the botanic garden, to wit: the hot bed frames, the conservatory or green house, and its appendages, the dwelling house, the hot houses and their back buildings, the lodges, the gates and the fences around the land, including the wells, at the sum of twenty-nine thousand three hundred dollars.”

- Gentle, Andrew, January 22, 1810, on the valuation of plants in the Elgin Botanic Garden (Hosack 1811: 53–54)[24]

- “The sum of fourteen thousand three hundred and eighty dollars and fifty-nine cents, is, I believe, to the best of my judgment, the value of your indigenous and exotic plants, tools, & c. at Elgin.”

- Hastings, John, Frederick Pursh, and John Brown, January 24, 1810, on the valuation of the plants in the Elgin Botanic Garden (Hosack 1811: 53)[24]

- “We, the subscribers, in committee assembled, for the valuation of the plants, trees, and shrubs, including garden tools and utensils, necessary for the cultivation of the same, as appertaining to the green house, hot houses, and grounds of the botanic garden, at Elgin, after a very particular inventory and examination of the improvements, are unanimously agreed, that, to the best of our knowledge and ability, we consider them to be worth the sum of twelve thousand six hundred and thirty-five dollars and seventy-four and half cents.

- “John Hastings, Nursery-man, Brooklyn, L.I.

- “Frederick Pursh, Botanist.

- “John Brown, Nursery-man.”

- Hosack, David, 1810, Description of the Elgin Garden (1810: 1–4)[31] back up to History

- “ . . . The view from the most elevated part of Elgin-ground, is variegated and extensive. The East and North Rivers, with their vast amount of navigation, are plain in sight. Beyond these great thoroughfares of business, the fruitful fields of Long-Island, and the picturesque shores of New-Jersey, give beauty and interest to the prospect. . . .

- "The conservatory and hot-houses present a front of one hundred and eighty feet. They are not only constructed with great architectural taste and elegance, but experience has also shown, they are well calculated for the preservation of the most tender exotics that require protection from the severity of our climate. The grounds are also arranged and planted agreeably to the most approved stile of ornamental gardening. The whole is surrounded by a belt of forest trees and shrubs judiciously chequered and mingled; and enclosed by a well constructed stone-wall. [Fig. 7] back up to History

- “The interior is divided into various compartments, not only calculated for the instruction of the student in Botany, but subservient to agriculture, the arts, and to manufactures. A nursery is also begun, for the purpose of introducing into this country the choicest fruits of the table. Nor is the kitchen garden neglected in this establishment. An apartment is also devoted to experiments in the culture of those plants which may be advantageously introduced and naturalized to our soil and climate, that are at present annually imported from abroad. . . .

- “The forest trees and shrubs which surround the establishment, first claim [the visitor’s] attention. Here are beautifully distributed and combined the oak, the plane, the elm, the sugar maple, the locust, the horse chesnut, the mountain ash, the basket willow, and various species of poplar. In front of these, a similarly varied collection of shrubs, natives and foreign, compose an amphitheatre, which, winding with the walks, presents at every step something new and engaging. On the other side the eye reposes on the green lawn which is occasionally intercepted with groups of trees and shrubs happily adapted to its varied surface.

- “In extending his walks to the garden, on each side, he [the visitor] is equally gratified and instructed by the numerous plants which are here associated in scientific order, for the information of the student in Botany or Medicine. Here the Turkey rhubarb, Carolina pink-root, the poppy and the foxglove, with many other plants of the Materia Medica, are seen in cultivation. . . .

- “As he proceeds he arrives at a nursery of the finest fruits, which the proprietor has been enabled to procure from various parts of the world, and from which the establishment will hereafter derive one of the principal means of its support.

- “The visitor next comes in view of a pond of water devoted to the varieties of nymphoea, pontederia and other aquatics which adorn its surface, while the adjacent grounds which are moist afford the proper and natural soil for a great variety of our most valuable native plants. The rhododendrons, magnolias, the kalmias, the willows, the stuartia; the candleberry myrtle; the cupressus disticha, and the sweet-smelling clethra alnifolia, here grow in rich luxuriance, and compose a beautiful picture in whatever direction they fall under his eye. . . .

- “Here a rocky and elevated spot attracts his attention, by the varied species of pine, juniper, yew, and hemlock, with which it is covered. There a solitary oak breaks the surface of the lawn; here a group of poplars; there the more splendid foliage of the different species of magnolia, intermixed with the fringe tree, the thorny aralia, and the snow drop halesia, call his willing notice.

- “Entering the green-house, his eye is saluted with a rich and varied collection: the silver protea, the lemon, the orange, the oleander, the citron, the shaddock, the myrtle, the jasmine and the numerous and infinitely varied family of geranium, press upon his view, while the perfumes emitted from the fragrant daphne, heliotropium, and the coronilla no less attract his notice than do the splendid petals of the camellia japonica, the amaryllis, the cistus, erica and purple magnolia.

- “In the hot-house he finds himself translated to the heat of the tropics. Here he observes the golden pine, the sugar cane, the cinnamon, the ginger, the splendid strelitzia, and ixora coccinea intermixed with the bread fruit, the coffee tree, the plantain, the arrow root, the sago, the avigato pear, the mimosa yielding the gum arabic, and the fragrant farnesiana. . . .

- “In front of the buildings are several beautiful clumps composed of the more delicate and valuable shrubs intermingled with a great variety of roses, kalmias and azaleas. Their borders are also successively enamelled with the crocus, the snow drop, the asphodel, the hyacinth, and the more splendid species of the iris.

- “Here also is viola tricolor . . . saluting the senses with its beautiful assemblage of colours but yielding in fragrance to its rival viola odorata which . . . also adds zest to this delicious banquet.”

- Anonymous, July 1810, description of the Elgin Botanic Garden (1811: 116–17)[32]

- “Among the number of those distinguished friends of science in Europe, who have manifested an ardent desire for the extension of useful knowledge in these states, may be justly esteemed Monsieur [André] THOUIN, the celebrated professor of Botany and Agriculture, at the Jardin des Plantes of Paris. . . . Dr. Hosack, the proprietor of the Elgin Botanic Garden, has repeatedly been favoured by him with a great variety of seeds, from the rarest and most valuable plants of the continent; and he is happy to add, that they have always been received in such a state of preservation, as scarcely in a single instance to have frustrated the liberal intentions of the donor. Indeed, many of the most valuable plants in his collection are the products of the seeds presented him by Monsieur THOUIN.

- “To the Hon. SAMUEL L. MITCHELL [sic], M.D. Professor of Natural History . . . in the College of Physicians, the proprietor of the Botanic Garden is also indebted for many valuable additions made to his collection of living plants, as well as for many specimens added to his Herbarium, collected by the same gentleman, during his residence at Washington, (as Senator of the United States,) and in the Western parts of the state of New-York, when on his late tour to the falls of Niagara. . . .”

- David Hosack, August 9, 1810, letter to Daniel Hale, the New York Secretary of State (quoted in Robbins 1964: 83)[33]

- “A work is preparing in which the native plants are to be painted and engraved for publication taken from those now growing in Elgin Botanic Garden. Artists are engaged and at this moment are at work under my direction. They are employed with the understanding they could complete the work they are now preparing.”

- Mr. B, October 3, 1810, describing his objections to the state purchase of Elgin Botanic Garden (Columbian 1, no. 287: n.p.)

- “As this spot has engrossed much of the public attention; and as its vast utility and splendor, and the immense fortune said to have been consumed in the embellishment of it have long been blazoned through the country, you may readily imagine that I expected to find something, if not rivalling, at least not inferior to, what you and I have witnessed in Europe. I was prepared to see a garden possessing all the various exotics of the celebrated Jardin national des plantes, and outstripping in the splendor of its disposition the Thulleries, the Champs Elisees, the Bois-de-Boulogne, of France, and Hyde Park and Kensington, of England. My fancy pictured to me something very magnificent. I imagined an entrance of massive gates, crowned with crouching lions; winding woods whose recesses were adorned with winged Mercuries, Cupids, Naiads and timid Fauns. I fancied grottos, and knolls, and mossy caverns, and irriguous fountains, and dolphins vomiting forth huge cascades, and griffons, and chateaus. All that we find in Shenstone’s Leasows [sic], or the idyls of Virgil or Gesner, were marshalled before my mental speculation. Nor is it at all astonishing that my imagination should have been thus creative, when you reflect on the enormous value which has been set up on this garden by the appraisers appointed by law. One hundred and three thousand dollars, you know, is about four times as much as either ‘Mousseux,’ the splendid retreat of the duke of Orleans, or ‘Le Petit Trianon’, the once luxurious abode of Marie Antoinette, were sold for.

- “Thus I was musing, as we passed along what is called the middle or New Boston road, when Mr. W. suddenly roused me with ‘Here’s Elgin.’ I looked around me, but saw no Elgin, when my friend, pointing to the spot, reiterated with emphasis, ‘Here, this is Elgin.’ It is impossible for me, my dear friend, to describe to you my sensations, when assured that what I saw, was the Botanic Garden, so much talked of last winter, and whose importance and splendor were the constant theme of encomium. My sensations were indescribable, tumbled as I was in a moment from the very acme of ardent expectation, into the Trophonian abyss of disappointment. I did not know whether to vent my execrations, or my laughter. There never was in the world, such a piece of downright imposture as this Botanic Garden, or as it is dignifiedly called Elgin. Unless it were pointed out to a traveller, it would utterly escape his notice. Take away from it, the ‘Orangerie’ or Greenhouse, which stands at the remote end of it, and it looks more like one of those large pasture-grounds near Albany, in which the western drovers refresh their cattle, after a sweaty march, than a Botanic Garden. It is a lot of twenty acres, with no other buildings on it but the Green-house just mentioned, which has two small wings, and two other buildings of about twelve feet square, fancifully called porter’s lodges (because there are no porters in them) one of which is placed at each gate. There is a small culinary garden on the western side, laid out in the common way in squares; and the rest of the grounds are in grass. No fruit whatever is to be found here; no large trees to furnish a retreat from the meridian sun; no little porticos; no knolls; nor in fine is there any thing which tends to embellish or diversify the grounds. Barring the green-house, which is like those generally found in private gardens, the tout-ensemble of this celebrated Elgin, has, as already observed, the air of a common pasture-ground. It has none of those rural beauties which one would expect, and which Virgil so charmingly describes,

- “‘Hic latis otia fundis, Speluncae, vivique lacus, hic frigida Tempe Mugitusque bovum, molesque sub arbore somni.’

- “Thinking, however, that this spot, although totally devoid of every species of beauty and ornament, might still be well stocked with all the varieties of exotic and indigenous plants, ‘from the cedar of Lebanon down to the hyssop of the wall,’ we visited the interior of the green-house. There we found orange and lemon trees, geraniums, two or three coffee and pine-apple plants, and all those little quelques choses which are usually to be seen in the gardens of private gentlemen, but nothing whatever of national importance.

- “Such, my friend, is what is absurdly called the botanic garden. . . .”

- Mr. D., October 15, 1810, defending the state acquisition of Elgin Botanic Garden from the points raised in the letter of Mr. B, above (Columbian 1, no. 297: n.p.)

- “During my visit to New-York I have also prevailed on our mutual friend, Mr. W. to accompany me to the Botanic Garden; and here again I must differ from you entirely. The reason for this difference arises from our having formed different systems as to what ought to constitute a Botanic Garden. My idea of an establishment of that kind is, that it ought to comprehend useful trees, shrubs and plants, domestic, naturalized and exotic, arranged in a proper state for use and preservation, and with a view to display their qualities, characters, properties and uses to the best advantage. Jet d’eaus [sic], artificial cascades, purling streams, mossy caverns, porticos, knolls, grottos, griffons and dolphins vomiting forth water, are foreign from the nature of a Botanic establishment; and however pleasant they may be at a gentleman’s country seat, or in a pleasure garden, yet surely nothing is more ridiculous than to require them in a scientific institution. I perceive, my friend, that your prolific imagination was teeming with the arbors, and summer-houses, and mead and cakes, and ice creams, of our far-famed Columbia Gardens on the Hill of Albany; and that you were dreaming of the fire-works, rockets and vertical suns, and water bells, and other ingenious contrivances, of monsieur Delacroix; and that your fancy was even insensibly tinctured with the mossy seats, umbrageous arbors, and sunny banks of the celebrated garden of Petit Paphos; or most assuredly you would not have faulted the poor Botanic Garden for not being an ornamental garden, or for not being laid out into elegant walks like the Leasowes of Shenstone, or the Twickenham of Pope. I observe that you have drawn freely upon lord Orford’s ideas of gardening, which, however just when properly applied, cease to be so when irrelevant. When I visited the garden, I did not exclaim in the language of reprobation, ‘Here is no reading-room like Cook’s, no cabinet of natural history like Trowbridge’s, no baths like M’Donald’s, no museum like Scudder’s, no water-works like Corre’s, no fireworks like Delacroix’s, no city library, no serpentine rivers, no chateaus, no steeples, no men in the moon.’ But I took a view of the grounds; I found them well laid out for the growth and preservation of the vegetables which occupied them, furnished with a great variety and assortment to the value of 12,000 dollars, and which the state is to receive gratuitously. I also observed green-houses and hot-houses of great extent and expense, and extremely well calculated to protect them against cold and moisture. In short, I discovered the greatest collection of valuable vegetables which I ever witnessed; and whether there were knolls or grottos, I did not indeed take the trouble to inquire; for which sin of omission I must most humbly crave your indulgence.”

- Hosack, David, March 12, 1811, preface and addendum to Hortus Elginensis (Hortus 1811: v–x, 66)[34]

- “The establishment of a Botanic Garden in the United States, as a repository of the native plants of this country, and as subservient to the purposes of medicine, agriculture, and the arts, is doubtless an object of great importance. Impressed with the advantages to be derived from an institution of this nature, I have anxiously endeavoured ever since my appointment to the professorship of Botany and Materia Medica in Columbia College, to accomplish its establishment. Disappointed, however, in my first applications to the legislature of this State, soliciting their assistance in so expensive and arduous an undertaking, I resolved to devote my own private funds to the prosecution of this object; trusting, that when the nature of the institution should be better, and more generally known, and its utility fully ascertained, it would receive the patronage and support of the public.

- "Accordingly, in the year 1801, I purchased of the Corporation of the city of New-York, twenty acres of ground . . . distant from the city about three miles and an half. The view from the most elevated part, is variegated and extensive, and the soil itself of that diversified nature, as to be particularly well adapted to the cultivation of a great variety of vegetable productions. The greater part of the ground is at present in a state of promising cultivation, arranged in a manner the best adapted to the different kinds of vegetables, and planted agreeably to the most approved style of ornamental gardening. Since that time, an extensive conservatory, for the more hardy green house plants, and two spacious hot houses, for the preservation of those which require a greater degree of heat, the whole exhibiting a front of one hundred and eighty feet, have been erected, and which, experience has shown, are well calculated for the purpose for which they were designed. The whole establishment is surrounded by a belt of forest trees and shrubs, both native and exotic, and these again are enclosed by a stone wall, two and an half feet in thickness, and seven feet in height. back up to History

- “As it has always been a primary object of attention to collect and cultivate in this establishment, the native plants of this country, especially such as are possessed of medicinal properties, or are otherwise useful, such gardeners as were practically acquainted with our indigenous productions, have been employed to procure them: how far this end has been attained, will be best seen by an examination of the Catalogue.

- “Although much has been done by the governments of Great-Britain, France, Spain, Sweden, and Germany, in the investigation of the vegetable productions of America: although much has been accomplished by the labours of [Mark] Catesby, [Pehr] Kalm, [Friedrich Adam Julius von] Wangenheim, [Johann David] Schoepf, [Thomas] Walter, and the Michaux [André and François André]; and by our countrymen [John] Clayton, the Bartrams [John and William], [Cadwallader] Colden, [Gotthilf Heinrich Ernst] Muhlenberg, [Humphry] Marshall, [Manasseh] Cutler, and the learned Professor [Benjamin Smith] Barton of Pennsylvania, much yet remains to be done in this western part of the globe. The numerous articles of medicine which this country has already furnished; the variety of soils and climates which it comprehends, encourage the belief, that many more remain to be discovered, and that the Materia Medica may still be enriched by the addition of many indigenous plants, whose virtues yet remain undiscovered.

- “Another object of importance is, to afford to students of medicine, the means of acquiring a knowledge of the natural history of plants, and the principles of botanic arrangement; a science intimately connected with their profession, as it not only enables them to distinguish one plant from another, but frequently leads to an acquaintance with their medicinal virtues. For this purpose the grounds are divided into different compartments, calculated to exhibit the various plants according to their several properties: and these again are so arranged as to afford a practical illustration of the systems of botany at present most esteemed, viz. the sexual system of Linnaeus, and the natural orders of [Antoine Laurent de] Jussieu.

- “Hitherto the botanical gardens of Edinburgh, Oxford, Cambridge, London, Paris, Copenhagen, Leyden, Upsal, Goettengen, &c. have instructed the American youth in this department of medical education; and it is in some degree owing to those establishments that the universities and colleges of those places have become so celebrated, and have been resorted to by students of medicine from all parts of the world. . . .

- "I avail myself of this occasion to observe, that as soon as measures may be taken by the Regents of the University for the permanent preservation of the Botanic Garden, it is my intention immediately to commence the publication of AMERICAN BOTANY, or a Flora of the United States. In this work it is my design to give a description of the plant, noticing its essential characters, synonyms, and place of growth, with observations on the uses to which it is applied in medicine, agriculture, or the arts; to be illustrated by a coloured engraving, in the same manner in which the plants of Great-Britain have been published by Dr. J[ohn]. E[dward]. Smith, in his English Botany. Considerable progress has already been made in obtaining materials for this publication: many of the drawings will be executed by Mr. James Inderwick, a young gentleman of great genius and taste, and others by John Le Conte, Esq. whose acquaintance with botany and natural history in general will enable him to execute this part of the work with great fidelity. In Mr. [Frederick] Pursh, whose name has already been mentioned, I shall have a very industrious and skilful botanist to collect from different parts of the union such plants as have not yet been assembled at the Botanic Garden.” back up to History

- Hosack, David, March 12, 1811, A Statement of Facts Relative to the Establishment and Progress of the Elgin Botanic Garden (1811: 7, 14–15)[24] back up to History

- “Persuaded of the advantages to be derived from the institution of a botanic garden, which could be made the repository of the native vegetable production of the country, and be calculated to naturalize such foreign plants are distinguished by their utility either in medicine, agriculture, or the arts, as well as for the purpose of affording the medical student an opportunity of practical instruction in this science, I, immediately after my appointment as professor [of botany and materia medica] in the college, endeavoured to accomplish its establishment. . . .

- “I still, however, did not abandon the hope of ultimately obtaining legislative aid, and therefore continued, as before, my exertions to increase the collection of plants which I had begun, and to extend the improvements for their preservation. Accordingly, in 1806, I obtained from various parts of Europe, as well as from the East and West-Indies, very important additions to my collection of plants, especially of those which are most valuable as articles of medicine. I also erected a second building for their preservation, and laid the foundation of a third, which was completed the following year. In the autumn of the same year, 1806, I published a Catalogue of the plants, both native and exotics, which had been already collected, amounting to nearly 2000 species. . . .

- “I had now erected, on the most improved plan, for the preservation of such plants as require protection from the severity of our climate three large and well constructed houses, exhibiting a front of one hundred and eighty feet. . . .The greater part of the ground was brought to a state of the highest cultivation, and divided into various compartments. . . .

- “The whole establishment was enclosed by a stone wall, two and an half feet in breadth, and seven and an half feet high. . . . Add to all this . . . the additional costs for the continual increase in the number of plants, particularly of those imported from abroad, though in this respect I was liberally aided by the contributions of my friends, both in Europe and in the East and West-Indies.”

- Anonymous [David Hosack?], July 1811, “Sketch of the Elgin Botanic Garden in the Vicinity of New York,” (1812: 1–4)[35] back up to History

- “This institution, the first of the kind established in the United States, is situated about three and a half miles from this city, on the middle road between Bloomingdale and Kingsbridge. . . .

- “Immediately after the purchase, the proprietor, at a very considerable expense, had the grounds cleared and put in a state of cultivation, arranged in a manner the best adapted to the different kinds of vegetables, and planted agreeably to the most approved stile of ornamental gardening. . . .

- “By the distinguished liberality of several scientific gentlemen in this country, there were in cultivation at the commencement of 1805 nearly fifteen hundred species of American plants, besides a considerable number of rare and valuable exotics. . . .

- “Recently the institution has been committed to the superintendence of the trustees of the college of physicians and surgeons of this city, to be by them kept in a state of preservation, and in a condition fit for all medical students as may resort thereto for the purpose of acquiring botanical science. It is confidently hoped, that as the improvements of this establishment for nearly ten years, while in the hands of a private individual, have far exceeded the expectations of the most sanguine, that its future progress will be proportionably great under its present governance.”

- Anonymous [“A Correspondent”], c. October 1811, description of botany classes held at the Elgin Botanic Garden (1812: 154, 158–159)[36] back up to History

- “After he had finished the geological and mineralogical parts of his course, which he elucidated from his own select and ample cabinet of fossils, Professor Mitchill entered upon the vegetable kingdom. He discoursed day after day upon the anatomy and physiology of seeds, plants, and flowers; and when he had proceeded far enough at the college in town, he adjourned to meet his audience at the botanical garden of Elgin, about three miles in the country.

- “There, in the presence of his numerous auditors, he demonstrated the component parts of the flower, and developed the principles of the Linnaean system. . . .

- “During the discussion which took place on the history of the vegetable kingdom, Professor Mitchill made repeated visits, with his disciples, to the garden of Elgin, founded by Dr. Hosack, but now the property of the state. And, while he was occupied in the classification, description and discrimination of plants, it was observed, that the two promising young botanists, Dr. Caspar W. Eddy and Mr. James Inderwick, acted as his assistants; the former, in demonstrating the marks peculiar to the species, and the latter, in expounding the characters which distinguish the genus, in the presence of the numerous attendants whom the occasion had led to embark in this delightful study. The purchase of this valuable establishment is not less useful to natural science than honourable to public spirit. The college of physicians, who are curators in behalf of the regents, take every care that repairs are made to the conservatory, hot house and fences, and that the plants are well nursed and attended.”

- Anonymous, 1811, commenting on Hosack’s recent publications on the Elgin Botanic Garden (The Medical and Physical Journal 26: 162–66)[37]

- “Though the collection in the Elgin Garden is not so large as in some older establishments in Europe, it is respectable both for number and quality. Of the indigenous plants of America we notice 1215 species: among these upwards of 200 are employed in medicine. Of plants possessing medicinal properties this seems a great number, but many of them possibly derive their title from popular opinion only; but even this title, as founded on a species of experience, is not to be slighted. Some of them have an established reputation: cinchona, ipecacuanha, jalapium, & c. are instances. It is curious fact in the history of Medical Botany, that when Europe remained in utter darkness on this subject, the Mexicans had appropriated a considerable space of ground, near the capital, to the sole purpose of rearing the indigenous medicinal plants. . . .

- “No region of the earth seems more appropriate to the improvement of Botany, by the collecting and cultivating of plants, than that where the Elgin Garden is seated. Nearly midway between the northern and southern extremities of the vast American continent, and not more than 40 degrees to the north of the equator, it commands resources of incalculable extent; and the European Botanist will look to it for additions to his catalogue of the highest interest. The indigenous Botany of America possesses most important qualities, and to that, we trust, Prof. Hosack, the projector, and indeed, the creator of this Garden, will particularly turn his attention. It can hardly be considered as an act of the imagination, so far does what has already been discovered countenance the most sanguine expectations, to conjecture, that in the unexplored wilderness of mountain, forest, and marsh, which composes so much of the western world, lie hidden plants of extraordinary forms and potent qualities.

- “From the scientific spirit and persevering industry of Dr. Hosack, every thing may be augured. Already has he projected an AMERICAN BOTANY, or a Flora of the United States, to be illustrated with coloured Plates, similar to those in the English Botany of our ingenious countryman, Dr. [James Edward] Smith. Considerable progress, we are informed, has already been made in obtaining materials for this work; but we regret that its completion depends on a contingency—the permanent preservation of the Elgin Botanic Garden. In the madness of political contention, in the apathy with which governments contemplate the advance of science, in the illiberal finesse and the low juggling of party, we may look for the occasional destruction or suspension of every rational project; but we hope these accidents will not frustrate the enlarged and enlightened intention of Dr. Hosack, but rather induce him to extend his Flora, and make the whole of the American continent his GARDEN.”

- Anonymous, April 1812, “Dr. Eddy’s Lectures on Botany” (American Medical and Philosophical Register 2: 466–67)[38]

- “Dr. C[aspar] W[istar] Eddy, of this city, has announced his intention of delivering a course of Lectures on Botany, to commence on the first Wednesday in May next. . . . During the whole course, the lecturer will avail himself of all the advantages calculated to render the instruction that may be given, a system of practical botany; and for this purpose, repeated visits will be made to the state botanic garden. . . . We shall only add, that a science in itself highly useful and agreeable, will possess additional claims to attetion, when unfolded in the able manner now proposed.”

- Spafford, Horatio Gates, 1813, describing the Elgin Botanic Garden (1813: 45–46)[39]

- “BOTANIC GARDEN. The Elgin Botanic Garden, in the city of New-York, the first institution of the kind in the United States, is now the property of the state. . . . Among the distinguished friends and patrons of science in this state, a common sentiment had long prevailed, friendly to the establishment of a Botanic Garden. Several unsuccessful attempts had been made to engage public aid for this purpose; and their having failed, while it detracts nothing from the reputation of the state, has ensured a better success to the institution, growing up under the zealous efforts of individual enterprize, which will ensure lasting fame to its principal founder. . . . In 1801, having failed in all attempts for public aid, the zeal and enterprize of Dr. Hosack, determined him to attempt the establishment on his own account. Accordingly he purchased 20 acres of ground of the corporation of New-York. . . . The soil is diversified, and peculiarly well adapted to the cultivation of a great variety of plants. The whole was immediately enclosed by a stone wall, and put in the best state for ornamental gardening; and a conservatory was erected for the preservation of the more hardy green-house plants. A primary object was to cultivate the native plants, possessing any valuable properties, found in this country; and in 1805, this establishment contained about 1500 valuable native plants, beside a considerable number of rare and valuable exotics. In 1806, it contained in successful cultivation, 150 different kinds of grasses, and important article to an agricultural people. . . . A portion of ground was set apart for agricultural experiments; and all the friends to experimental science and a diffusion of knowledge saw that the institution promised all that had been expected from it; and that the professor’s knowledge and genius were occupied on a congenial field. . . .

- “The view from the most elevated part of Elgin ground, is extensive and variegated. The aspect of the ground, is a gentle slope to the E. and S. The whole is enclosed by a well constructed stone wall, lined all round by a belt of forest trees and shrubs. The conservatory and hot-houses present a front of 180 feet. The various allotments of ground, are chosen with as much taste as good judgment for the varied culture;—and the rocky summit, the subsiding plain, and the little pool, have each their appropriate products. The herbarium, the kitchen garden, the nursery of choice fruits from all quarters and climes, and the immense collection of botanical subjects elegantly arranged and labelled, display the industry, taste and skill of a master. A very extensive Botanical library belongs to the late proprietor, who is now a professor in the University, and delivers a summer course of lectures on Botany. . . . The garden is now committed to the superintendence of the college of Physicians and Surgeons, without any charge to the state.”

- Pursh, Frederick, 1814, describing Elgin Botanic Garden (1814: 2:xiv)[40]

- “While I was engaged in arranging my materials for this publication, I was called upon to take the management of the [Elgin] Botanic Garden at New York, which had been originally established by the arduous zeal and exertions of Dr. David Hosack, Professor of Botany, &c. as his private property, but has lately been bought by the Government of the State of New York for the public service. As this employment opened a further prospect to me of increasing my knowledge of the plants of that country, I willingly dropped the idea of my intended publication for that time, and in 1807 [sic; 1809] took charge of that establishment.

- “Here I again endeavoured to pay the utmost attention to the collection of American plants, as the establishment was principally intended for that purpose. In this I was supported by my numerous botanical connections and friends, among whom I must particularly mention John Le Conte, Esq. of Georgia, whose unremitting exertions added considerably to the collection, particularly of plants from the Southern States.

- “The additions to my former stock of materials for a Flora were now considerable, and in conjunction with Dr. D. Hosack I had engaged to publish a periodical work, with coloured plates, all taken from living plants, and if possible from native specimens, on a plan similar to that of Curtis’s Botanical Magazine; for which a great number of drawings were actually prepared. But . . . in 1810, took a voyage to the West Indies, . . . from which I returned in the autumn of 1811.

- “On my return to New York, I found things in a situation very unfavourable to the publication of scientific works, the public mind being then in agitation about a war in Great Britain. I therefore determined to take all my materials to England, where I conceived I should not only have the advantage of consulting the most celebrated collections and libraries, but also meet with that encouragement and support so necessary to works of science, and so generally bestowed upon them there.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, February 18, 1818, letter to David Hosack concerning seeds from the Jardin des Plantes in Paris (1944: 578)[41]

- “I received some time ago from M. Thouin, Director of the Botanical or King’s garden at Paris, a box containing an assortment of seeds, Non-American. . . . I have therefore this day sent the box to Richmond . . . to be forwarded to you for the use of the Botanical Garden of N. York. . . . I am happy in this disposition of it to fulfill the good intentions of the donor, and to make it useful to your institution.”

- Esqrier Frères & Cie., April 2, 1821, letter from Havre to Thomas Jefferson concerning seeds from the Jardin des Plantes in Paris[42]

- “We have the honor of informing you that we have put on The American ship Cad[mus] . . . Capn. Wethlet [sic; Whitlock], a small Box of seeds, which is sent to you by the Managing Directors of the King’s Garden in Paris. . . .

- “We have sent this letter as well as some other ones for several people in the United States, to the address of Mister Hosack, Director of the Botanical Garden of the State of New york.

- “Corresponding in this day for the Administrators of the King’s Museum and Garden, we are taking the liberty of offering you our Services, for your relationship with this administration, or for anything else that could be of interest to you in France.”

- Eyrien Frères & Cie., April 2, 1821, letter from Havre to James Madison concerning seeds from the Jardin des Plantes in Paris (Madison 2013: 2:292–93)[43]

- “The administrators of the King’s Garden at Paris have forwarded to us a package of seeds for you. We added it with some other packages for the same shipment and sent it all on board the American ship Cadmus, Capt. Whitlock, addressed to Mr. Hosack, director of the Botanical Garden of the State of New York, from whom you will please request it.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, June 25, 1821, letter to Jonathan Thompson concerning seeds from the Jardin des Plantes in Paris[44]

- “I am thankful to you for your notice of the 14th respecting a box of seeds—this comes from the king’s garden at Paris. they send me a box annually, depending on my applying it for the public benefit. I have generally had them delivered for a public garden at Philadelphia or to Dr Hosack for the Botanical garden of N. York. I am inclined to believe that he now recieves such an one from the same place. if he does not, be so good as to deliver it to him. but if of no use to him let it come to Richmond to the care of Capt Bernard Peyton, my correspondent there, and your note of any expence attending it will be immediately replaced either by him or myself.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, July 12, 1821, letter to David Hosack concerning seeds from the Jardin des Plantes in Paris[45]

- “I recieved a letter lately from mr Thompson, Collector of New York, informing me of a box of seeds from the king’s gardens at Paris addressed to me. I rather suppose you recieve one annually from the same place for your botanical garden, but was not certain. I desired him therefore to present it to you if acceptable for your garden.”

- Spafford, Horatio Gates, 1824, describing the Elgin Botanic Garden (1824: 605)[46]

- “Botanic Garden.—This is a very respectable establishment, situated on New-York Island, in the 9th Ward of the City, 4 miles N. of the City Hall. It was purchased by the State, in 1810, and is an appendage of the Colleges in New-York. It comprises 20 acres of ground, and embraces a great variety of indigenous, naturalized, and exotic vegetables. The situation is commanding, on the rising ground, which embraces a good variety of soil, aspect, and position, and Elgin Grove has as many visitants as the Botanic Gardens, chasing pleasure, or catching knowledge.”

Images

Map

Other Resources

Library of Congress Authority File

Notes

- ↑ Significantly, when David Hosack later quoted Mitchill, he altered his words to emphasize the garden’s practicality, changing Mitchill’s phrase “genteelest and most beautiful” to “most useful and most important”; see David Hosack, A Statement of Facts Relative to the Establishment and Progress of the Elgin Botanic Garden: And the Subsequent Disposal of the Same to the State of New-York (New York: C. S. Van Winkle, 1811), 6, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Christine Chapman Robbins, David Hosack: Citizen of New York (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1964), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hosack 1811, 7–10, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hosack 1811, 10, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, letter of July 25, 1803, to Dr. Thomas Parke, Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection, Boston Public Library, quoted in Robbins 1964, 65, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Preston Long, “The Woodlands: A ‘Matchless Place’” (master’s thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, Description of the Elgin Garden, The Property of David Hosack, M.D. (New York: The author, 1810), 1–4, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hosack 1810, view on Zotero; cf. David Hosack, A Catalogue of Plants Contained in the Botanic Garden at Elgin: In the Vicinity of New York, Established in 1801 (New York: T. & J. Swords, 1806), 4, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Caspar Wistar Eddy, “Plantae Plandomenses, or a Catalogue of the Plants Growing Spontaneously in the Neighbourhood of Plandome, the Country Residence of Samuel L. Mitchill,” Medical Repository 5, no. 2 (August–October 1807): 123–31, view on Zotero; Catalogue of the Alumni, Officers and Fellows of the College of Physicians and Surgeons in the City of New York (New York: Baker & Godwin, 1859), 22, 27, view on Zotero; Catalogue of Columbia College, in the City of New-York; Embracing the Names of Its Trustees, Officers, and Graduates (New York: Columbia College, 1844), 37, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Francis noted that his article was illustrated by “the ingenious Mr. Inderwick, a student of medicine of this city,” and Hosack wrote, “To my friend, Mr. Inderwick, I am indebted for the very beautiful drawing from which this engraving has been made.” See John W. Francis, “Case of Enteritis, Accompanied with a Preter-natural Formation of the Ileum,” American Medical and Philosophical Register 1 (July 1810): 39; see also 41, view on Zotero, and David Hosack, “Observations on Croup: Communicated in a Letter to Alire R. Delile, M.D. Physician in Paris,” American Medical and Philosophical Register 2 (July 1811): 43; see also 40, view on Zotero. Other drawings by Inderwick were published in David Hosack, “Case of Aneurism of the Femoral Artery: Communicated in a Letter to John Abernethy,” American Medical and Philosophical Register 3 (July 1812): 48, view on Zotero, and John W. Francis, Cases of Morbid Anatomy: Read before the Literary and Philosophical Society of New-York, on the Eighth of June, 1815 (New York: Van Winkle and Wiley, 1815), view on Zotero.

- ↑ The drawing accompanied a letter to Samuel Latham Mitchill in which Hosack wrote, “The following description of the plant by Mr. Curtis [in the Flora Londinensis] so perfectly corresponds with that with which our country is infested, that with the aid of the annexed drawing of the plant, made by my friend Mr. J. Inderwick, from the specimen you sent me, it will readily be recognised by the farmer into whose fields it may intrude itself.” See David Hosack, “Botanical description of the Canada Thistle or Cnicus Arvensis . . . Communicated in a letter to the Hon. S. L. Mitchill, M.D.,” American Medical and Philosophical Register 1 (October 1810): 211–12, view on Zotero. Inderwick was house surgeon at the New York Hospital for one year from February 1812 until February 1813. Stephen Decatur appointed him acting surgeon of the Argus on May 8, 1813. He died when his ship was lost at sea in 1815. See James Inderwick, Cruise of the U.S. Brig Argus in 1813: Journal of Surgeon James Inderwick, ed. Victor H. Palsits (New York: New York Public Library, 1917), 3–4, view on Zotero; William S. Dudley, The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History, 2 vols. (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 1992), 2: 219–22, 275–76, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Eatton Le Conte, “Catalogue Plantarum Quas Sponte Crescentes in Insula Noveboraco, Observavit Johannes Le Conte, Eq.: Sub Forma Epistolae Ad D. Hosack, M.D. Missae,” American Medical and Philosophical Register 2 (1811): 134–41, view on Zotero. See also John Eatton Le Conte, “Observations on the Febrile Diseases of Savannah; in a Letter to Dr. Hosack, from John Le Conte, Esq., Woodmanston, December 18, 1809,” American Medical and Philosophical Register 4 (1814): 388–90, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Pursh, Flora Americae Septentrionalis; Or, a Systematic Arrangement and Description of the Plants of North America, 2 vols. (London: White, Cochrane, & Co., 1814), 1:xiv, view on Zotero. For Le Conte’s drawings, see: Viola Brainerd Baird, “The Violet Water-Colors of Major John Eatton LeConte,” American Midland Naturalist, 20 (1938), 245–47, view on Zotero; Calhoun, John V., “John Abbot’s ‘Lost’ Drawings for John E. Le Conte in the American Philosophical Society Library,” Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society, 60 (2006): 211–17, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For an overview of expenses recorded in Hosack’s memorandum book of 1803–1809, see Robbins 1964, 64, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Gentle, Every Man His Own Gardener; Or, a Plain Treatise on the Cultivation of Every Requisite Vegetable in the Kitchen Garden, Alphabetically Arranged. With Directions for the Green & Hothouse, Vineyard, Nursery, &c. Being the Result of Thirty-Five Years’ Practical Experience in This Climate. Intended Principally for the Inexperienced Horticulturist (New York: The author, 1841), iii–iv, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Pursh, Journal of a Botanical Excursion in the Northeastern Parts of the States of Pennsylvania and New York: During the Year 1807 (Philadelphia: Brinckloe & Marot, 1869), 87, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hosack 1811, 12, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robbins 1964, 79–84, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hosack’s report to the Trustees of the College of Physicians and Surgeons, August 30, 1813, quoted in Robbins 1964, 96, view on Zotero. For Hosack’s continued involvement in the garden, see, for example, David Hosack, “Report on Botany and Vegetable Physiology,” American Monthly Magazine and Critical Review 1 (May 1817): 47, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack to Clement C. Moore, October 16, 1816, quoted in Robbins 1964, 98; see also 97 for Dennison’s letter of the previous month, informing the College of Physicians and Surgeons of repairs and horticultural care required at the garden, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Addison Brown, The Elgin Botanic Garden, Its Later History and Relation to Columbia College (Lancaster, PA: New Era Printing Company, 1908), 15–19, view on Zotero; Robbins 1964, 97–98, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Brown 1908, 19, view on Zotero.

- ↑ “Introduction,” Transactions of the Society for the Promotion of Agriculture, Arts and Manufactures, Instituted in the State of New York 1 (1794), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 Hosack 1811, view on Zotero.

- ↑ François André Michaux, Travels to the West of the Alleghany Mountains in the States of Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessea, and back to Charleston, by the Upper Carolines . . . Undertaken, in the Year 1802, 2nd ed. (London: B. Crosby & Co. and J. F. Hughes, 1805), view on Zotero.

- ↑ MS letter in Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection, Boston Public Library, quoted in Timothy Preston Long, “The Woodlands: A ‘Matchless Place’” (master’s thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 1991), view on Zotero and Robbins 1964, 65, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hosack 1806, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack to Thomas Jefferson, Septmber 10, 1806, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498–1909, 6 vols. (New York: Robert H. Dodd, 1926), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, ed. J. Jefferson Looney, Retirement Series, 4 vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 2: 89–91, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hosack 1810, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Elgin Botanic Garden, New York,” American Medical and Philosophical Register 1 (1811), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robbins 1964, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, Hortus Elginensis, or, A Catalogue of Plants, Indigenous and Exotic, Cultivated in the Elgin Botanic Garden, in the Vicinity of the City of New-York : Established in 1801(New York : Printed by T. & J. Swords, 1811), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Sketch of the Elgin Botanic Garden in the Vicinity of New York,” American Medical and Philosophical Register 2 (1812), view on Zotero. Much of the article paraphrases Hosack’s Hortus Elginensis (1811), quoted above.

- ↑ Anonymous [“A Correspondent”], “Cultivation of Natural History in the University College of New-York,” American Medical and Philosophical Register 2 (1812), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Review of Hortus Elginensis and A Statement of Facts relative to the . . . Elgin Botanic Garden,” The Medical and Physical Journal 26 (July 1811): 162–66, view on Zotero.

- ↑ "Dr. Eddy’s Lectures on Botany,” American Medical and Philosophical Register 2 (1812), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Horatio Gates Spafford, A Gazetteer of the State of New-York: Carefully Written from Original and Authentic Materials, Arranged on a New Plan, in Three Parts (Albany: H. C. Southwick, 1813), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Pursh, Flora Americae Septentrionalis; Or, a Systematic Arrangement and Description of the Plants of North America, 2 vols. (London: White, Cochrane, & Co., 1814), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Esqrier Brothers & Co. to Thomas Jefferson, April 2, 1821, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ James Madison, The Papers of James Madison, ed. David B. Mattern et al. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013), 2:292–93, view on Zotero

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Jonathan Thompson, June 25, 1821, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to David Hosack, July 12, 1821, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Horatio Gates Spafford, Gazetteer of the State of New York (Albany: B. D. Packard, 1824), view on Zotero.