Orchard

(Hort-yard)

See also: Yard

History

The definitions of orchard found in both English and American garden treatises describe an enclosed space devoted to the growth of fruit trees.[1] Noah Webster, in his 1828 definition of the term, differentiated between British usage—as a department of the garden appropriated to fruit trees (chiefly apple)—and American usage—as any piece of land set with only apple trees. Webster’s focus on one species reflected the popularity of this fruit in early 19th-century America.[2]

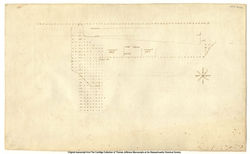

Some British treatises distinguished between a fruit garden and an orchard. For example, according to Jean de La Quintinie (translated by John Evelyn in 1693), fruit gardens (like kitchen gardens) were generally walled and thus could sustain espaliered fruit trees. In contrast, orchards typically were enclosed with natural barriers, such as hedges and ditches, and were planted with standard fruit trees. Thomas Jefferson, for example, indicated the use of thorn hedges surrounding his orchard [Fig. 1]. In American garden literature, the term “fruit garden” occurs in a few instances, as when George Washington referred to the space behind his stables laid out with closely set fruit trees.[3] The term also appeared in Thomas Green Fessenden’s New American Gardener (1833), but this may have been due more to the practice of emulation in treatise writing than to the circulation of the term in America. (Fessenden, in fact, borrowed heavily from his British predecessors.) More common to American culture was the term “orchard,” which appeared very early in accounts of the American designed landscape.

Although the American orchard was not considered a subgroup of a larger garden complex to the same degree as it was in the British flower garden, it was nevertheless recognized as part of the broader designed landscape associated with a residence or plantation. Like many other features of the American design landscape, such as canal, meadow, or wood, the orchard was both utilitarian and aesthetic. It united, in the words of Loudon, “[t]he agreeable with the useful” (1826). The primary function of orchards was growing fruit, and apples and peaches seem to have been the fruit of choice for many colonial and federalist landowners in New England and in the mid-Atlantic states. The orchard ground, as a cultivated area of land, also could be used for growing grass or hay under the trees. This practice was somewhat controversial, as indicated by the lengthy commentary on the subject by treatise writers. John Abercrombie (1817) suggested trimming the lower branches of trees to prevent damage by cattle.

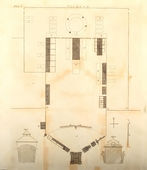

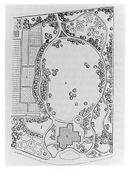

Like the planting of grasses in orchards, the arrangement of trees was disputed by treatise writers. John Smith’s 1629 account mentions the arrangement of fruit trees into rows, a practice recommended by numerous treatise writers. Another possibility, found in several treatises, was to arrange trees in a quincunx formation, where trees would be planted in a manner resembling the plan of a five-face on a die [Fig. 2]. Debate also focused on the spaces between trees that were aligned in rows and also on the distance between rows.

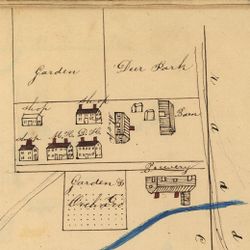

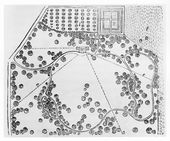

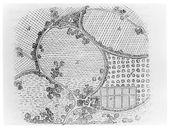

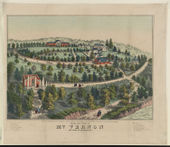

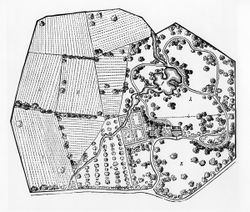

Images reveal much information about the arrangement of trees in American orchards. Orchards typically were represented as square or rectangular plots placed adjacent to or situated near houses, and they often were bounded by fences, ditches, or hedges [Fig. 3]. Most plots contained regularly arranged trees, as in Clarissa Deming’s orchard plan, after 1798 [Fig. 4]. The frequency, however, with which regularized arrangements of trees appear in images suggests that many images may have been governed by a visual convention dictating that orchards be represented with straight rows of trees. This convention is apparent in a 1757 view of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania [Fig. 5]. Nonetheless, a few plans imply that orchard trees could be arranged in patterns other than linear rows. A 1778 sketch by Thomas Jefferson of the orchard at Monticello depicts a pinwheel-like arrangement of fruit trees that included apple, peach, quince, pear, apricot, and plum [Fig. 6].

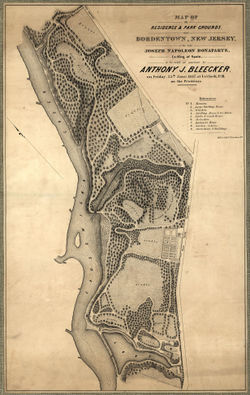

With the development of the so-called “natural” style in America in the early 19th century, orchards became more varied in character. The 1847 plan of Point Breeze in Bordentown, New Jersey, represents the orchard as an irregularly shaped piece of land located at a distance from the mansion and sited within woodlands [Fig. 7]. In Downing’s 1849 plan for a “picturesque orchard,” he broke with the convention of rigidly arranging trees in straight lines and presented them loosely clumped in groups “for the sake of effect.”

In travelers’ accounts of America, the term “orchard” figures prominently in descriptions of the settled countryside. In these texts, as well as in treatises and descriptions of specific estates, orchards were imbued with both utilitarian and aesthetic values. (The practical associations of husbandry with orchards distinguished them from groves, which except for citrus groves, were generally discussed in only aesthetic terms.) Orchards signaled planning for the needs of the future, since trees took many years to mature. William Penn, in his 1685 advertisement for potential colonialists, characterized an orchard as a property improvement and investment. Orchards also exemplified the careful grooming of the countryside by American settlers, who transformed uncultivated woods and fields into ordered plantations of fruit trees. Timothy Dwight, in particular, offered myriad orchard descriptions in order to conjure up his early 19th-century vision of America as a highly cultivated, prosperous nation. That very prosperity, however, eventually seemed to threaten the existence of orchards. According to Edward Sayers (1835), the expansion of America’s transportation network of railroads, canals, and roads promised to eradicate orchards as trees were cut down and not replaced. Yet 16 years later, Downing claimed that railroads and steamboats had, in fact, brought about a boom in orchards as farmers could then easily transport their produce by rail and thus capitalize upon such markets.

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Smith, John, 1629, describing the Charles River in Massachusetts (quoted in Miller and Johnson 1963: 2:399)[4]

- “in the maine you may shape your Orchards, Vineyards, Pastures, Gardens, Walkes, Parkes, and Corne fields out of the whole peece as you please into such plots, one adjoyning to another, leaving every of them invironed with two, three, foure, or six, or so many rowes of well growne trees as you will, ready growne to your hands, to defend them from ill weather.”

- Donck, Adriaen van der, 1655, describing New York, NY (quoted in Hedrick 1988: 55)[5]

- “The Netherlands settlers, who are lovers of fruit, on observing that the climate was suitable to the production of fruit trees, have brought over and planted various kinds of apple and pear trees which thrive well. . . . The English have brought over the first quinces, and we have also brought over stocks and seeds which thrive well and produce large orchards.”

- Anonymous, 1667, describing a proposed orchard in Somerset County, MD (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 247)[6]

- “[The planter stipulated in his will that his executors were] to make an orchard of 200 trees the one halfe winter fruite the other summer leaving sufficient fencing on it & aboute itt.”

- Glover, Thomas, 1676, describing fruits on plantations in his Account of Virginia (quoted in Martin 1991: 18)[7]

- “. . . few planters but that have fair and large orchards, some whereof have 1200 trees and upward bearing all sorts of English apples . . . of which they make great store of cider . . . likewise great peach-orchards, which bear such an infinite quantity of peaches.”

- Penn, William, October 12, 1685, in a letter to Richard Blome, describing Pennsylvania (quoted in Blome 1687: 127–28)[8]

- “3. . . . Say I have five thousand Acres, I will settle ten Families upon them in way of Village . . . they shall continue seven years, or more, at half increase, being bound to leave the Houses in repair, and a Garden and Orchard, I paying for the Trees, and at least twenty Acres of Land within Fence, and improved to Corn and Grass. The charge will come to about sixty pounds English each Family; at the seven years end, the improvement will be worth, as things go now, one hundred and twenty pounds, besides the value of the encrease of the Stock.”

- Thomas, Gabriel, 1698, describing Pennsylvania (quoted in Hedrick 1988: 77)[5]

- “There are many Fair and Great Brick Houses on the outside of the Town which the Gentry have built for their Countrey Houses . . . having a very fine and delightful Garden and Orchard adjoyning it, wherein is variety of Fruits, Herbs, and Flowers.”

- Byrd, William, II, January 3, 1712 and July 13, 1720, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd II, on the James River, VA (Wright and Tinling, eds., 1972: 428, 464)[9]

- “I walked into the orchard and ate so many plums that I could not sleep.”

- “In the afternoon I set my razor and then went to prune the trees in the young orchard and then I took a walk about the plantation and my wife and Mrs. Dunn came to walk with me.”

- Jones, Hugh, 1724, describing the Governor’s Palace, Williamsburg, VA (quoted in Hedrick 1988: 110)[5]

- “. . . a magnificent structure, built at publick Expense, finished and beautified with Gates, fine Gardens, Offices, Walks, a fine Canal, Orchards.”

- Anonymous, July 28, 1733, describing a property for sale in Charleston, SC (South Carolina Gazette)

- “A Plantation about two Miles above Goose-Creek Bridge . . . [having] an Orchard of very good Apple and Peach Trees.”

- Ball, Joseph, February 1734, letter regarding property in Virginia (Library of Congress, Joseph Ball Letterbook)

- “The young Peach orchard must be made up new all round, as Substantial, Close, Strong, and high, as I have made part of it already: and they must take up out of the old Peach orchard, what trees may be wanting to fill up that piece of Tobacco Ground in the young Peach orchard. And I would have all the rest of the Peach trees in the old orchard Cut down; and that Ground laid into the Little Pasture. This mowing of the trees must be in a proper time next Spring. . . .

- “The Peach orchard must be how’d up, and after that Chopt over, once, or twice, to kill the Broom grass, else the Grass will kill the trees.”

- Pinckney, Eliza Lucas, 1742, in a letter to Miss Bartlett, describing Wappoo Plantation, property of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, Charleston, SC (1972: 35)[10]

- “O! I had like to forget the last thing I have done a great while. I have planted a large figg orchard with design to dry and export them. I have reckoned my expence and the prophets to arise from these figgs, but was I to tell you how great an Estate I am to make this way, and how ’tis to be laid out you would think me far gone in romance.”

- Anonymous, February 1, 1746, describing in property for sale near Charleston, SC (South Carolina Gazette)

- “Whereas Thomas Wright intending to settle in Charles Town, there will be sold at his Plantation in the Parish of St. James’s Goosecreek. . . .

- “N. B. The said plantation [has] . . . An Orchard with several apple, Pear and Peach Trees under Fence, with a long Walk in the Middle.”

- Anonymous, August 17, 1747, describing property for sale in Somerset County, NJ (New York Gazette)

- “TO BE SOLD, A pleasant Country Seat, fitting for a Gentleman or Store-keeper . . . a good Orchard, containing about 200 Apple Trees, and may be extended at Pleasure.”

- Alexiowitz, Iwan, 1769, describing Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, vicinity of Philadelphia (quoted in Darlington 1849: 50)

- “He next showed me his orchard, formerly planted on a barren, sandy soil, but long since converted into one of the richest spots in that vicinage.”

- Fithian, Philip Vickers, April 3, 1774, describing Nomini Hall, Westmoreland County, VA (1943: 121)[11]

- “. . . as I look from my Window & see Groves of Peach Trees on the Banks of Nomini; (for the orchards here are very Large) and other Fruit Trees in Blossom.”

- Anburey, Thomas, May 20, 1778, describing Mystic, CT, and Lancaster County, PA (1789; repr., 1969: 2:215–16, 285–86)[12]

- “The trees are now in full blossom, and as every house has an orchard adjoining, the country looks quite beautiful; upon enquiry of the inhabitants, I find most of the European fruits have degenerated in New England, except the apple, which it is said, if it has not improved, it has multiplied exceedingly.”

- “Their [the Dumplers sect] little city [Euphrates] is built in the form of a triangle, and bordered with mulberry and apple-trees, very regularly planted. In the center of the town is a large orchard, and between the orchard and the ranges of trees that are planted round the borders, are their houses, which are built of wood, and three stories high.”

- Stuart, John Ferdinand Smyth (J .F. D. Smyth), 1784, describing Williamsburg, VA (quoted in Lockwood 1934: 2:53)[13]

- “These are called plantations and are generally from one to four or five miles distant from each other, having a dwelling house in the middle . . . at some little distance there are always large peach and apple orchards.”

- Giannini, Antionio, 1786, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (quoted in Nichols and Griswold 1978: 100)

- “The apples in the orchard below the garden are producing abundantly. All the varieties of cherry trees are growing well. The ‘Magnum bonum plumbs’ are turning out marvelously and so are the green gages. The apricots are growing satisfactorily. . . . The almonds are still alive but are not improving. The peaches are all doing well. . . . Has grafted many trees of the kinds TJ requested; but no one had told him about grafting the royal white, yellow, and red peaches. This will be done at once. They have not yet finished planting the apples of the north orchards, but the ones planted are doing well and will have a full crop next autumn.” [See Fig. 6]

- Dwight, Timothy, 1798, describing Boston, MA (quoted in Lockwood 1931: 1:26–27)[13]

- “‘Boston enjoys a superiority to all other great towns on this continent. . . . The soil is generally fertile, the agriculture neat, and productive; the gardening superior to what is found in most other places; the orchards, groves, and forests, numerous and thrifty.’”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1799, describing South Hadley, MA (1822: 3:262)[14]

- “Major White, a respectable inhabitant of South-Hadley, had an orchard, which stood on the North-Western declivity of a hill, of so rapid a descent, that every tree was entirely brushed by the winds from that quarter. The spot lay about four miles direcly South-Eastward from the gap between Mount Tom, and Mount Holyoke. Through this gap these winds blow, as you will suppose, with peculiar strength. Accordingly they swept the dew from this orchard so effectually, that its blossoms regularly escaped the injuries of such late frosts in the spring, as destroy those of the surrounding country. So remarkable was the exemption, that the inhabitants of South-Hadley proverbially styled such a frost Major White’s harvest; because his orchard yielded a great quantity of cider, which in such years commanded a very high price.”

- Parkinson, Richard, 1798–1800, describing the vicinity of Baltimore, MD (1805: 2:612–13)[15]

- “. . . from my own experience, what is the general custom of the people in regard to the orchards and fruit planted in fields in America, as it is not at all unusual to plant fields with fruit to the extent of from four to twenty acres: —my orchard [at Orange Hill] contained about six acres, three of which were planted with apples, the other three with peaches of various sorts . . . it being at some distance from the house, (which is the usual manner of planting them the first year).”

- Ogden, John Cosens, 1800, describing the garden of the recitation room and Inspector’s study, Nazareth, PA (1800: 46)[16]

- “The Pedagogium and town are seen from this place. In the rear is an orchard defended by a grove.”

- Anonymous, April 18, 1800, describing Willow Brook, seat of John Donnell, Baltimore, MD (Federal Gazette)

- “That beautiful, healthy and highly improved seat, within one mile of the city of Baltimore, called Willow Brook, containing about 26 acres of land, the whole of which is under a good post and rail fence, divided and laid off into grass lots, orchards, garden, &c. . . . The garden and orchard abounds with the greatest variety of the choicest fruit trees, shrubs, flowers, &c collected from the best nurseries in America and from Europe, all in perfection and full bearing.”

- Michaux, François André, 1802, describing an orchard in St. Anastasia, FL (1805: 349)[17]

- “It is fifty years since the seeds of this species [sweet orange] were brought from India, and given to an inhabitant of this island [Sant Anastasia], who has increased them so much as to have made an orchard of them of forty acres. I had an opportunity of seeing this fine plantation when I was in Florida, in 1788.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, January 2, 1802, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1987: 2:57)[18]

- “On the right [of the house] is an orchard, consisting principally of large cherry and peach trees. At the bottom of this orchard, and nearly opposite the eastern end of the house, is the venerable tomb, which contains the remains of the great Washington.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, c. 1804, describing improvements for Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (quoted in Martin 1991: 157)[7]

- “. . . all the farm grounds of Monticello had better be turned into orchard grounds of cyder [sic] apple & peach trees, & orchard grass cultivated under them.”

- Anonymous, August 9, 1805, describing in The Virginia Herald a property for sale in Stafford County, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “FOR LEASE, A Lot of Land. . . . Also, on the above lot there is . . . a considerable Orchard of young Apple trees of choice fruit, now in a bearing state.”

- Drayton, Charles, November 2, 1806, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia (1806: 58)[19]

- “The kitchen garden & Hort. yard/Orchyard, which I did not see, are, I suppose behind the Stables, & adjacent.”

- Flint, Timothy, 1816, describing his journey from Frankfort to Louisville, KY (quoted in Jones 1957: 10)[20]

- “Travelling through the village in this fertile region, where the roads are perfectly good, and where every elevation brings you in view of a noble farm-house, in the midst of its orchards, and sheltered by its fine groves of forest and sugar-maple trees, you would scarcely realize that the first settlers of the country, and they men of mature age when they settled it, were, some of them, still living.”

- Cobbett, William, 1819, describing Long Island, NY (Cobbett 1819: 12)[21]

- “The Orchards constitute a feature of great beauty. Every farm has its orchard, and, in general, of cherries as well as of apples and pears.”

- S., J. W., September 1829, describing André Parmentier’s horticultural and botanic garden, Brooklyn, NY (Gardeners’ Magazine 8: 72)

- “In short, this establishment is well worthy of notice as one of the few examples in the neighbourhood of New York, of the art of laying out a garden so as to combine the principles of landscape-gardening with the conveniences of the nursery or orchard.”

- Anonymous, October 15, 1830, “Trespassers in Orchards” (New England Farmer 9: 101)

- “The following is an abstract of the Statute 1818, Cap. 3d. for the prevention of trespasses in Orchards, and Gardens, &c.

- “Sec. 1. If any person enter upon any grassland, orchard, or garden, without permission, with intent to cut, destroy, take, or carry away, any grass, hay fruit, or vegetables, with intent to injure or defraud the owner: such person shall, on conviction, before a justice of the peace, forfeit and pay, for every such offence, a sum not less than two, nor more than ten dollars; and be also liable in damages to the party injured.”

- Dearborn, H. A. S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Harris 1832: 65)[22]

- “On the southeastern and northeastern borders of the tract can be arranged the nurseries, and portions selected for the culture of fruit-trees and esculent vegetables, on an extensive scale; there may be arranged the Arboretum, the Orchard, the Culinarium, Floral departments, Melon grounds, and Strawberry beds, and Green houses.”

- Bryant, William Cullen, February 26, 1834, in a letter to his brother, John Howard Bryant, describing Putnam County, IL (1975: 394)[23]

- “You talk in your letter to my wife of planting an orchard and eating the fruit of it if you live to be old. Why do you not graft your crab apple trees with scions produced from the older settlements of your state? You would then have apples in a very few years. Did you ever think of this?”

- Martineau, Harriet, 1835, describing Northampton, MA (1838: 2:83)[24]

- “The stage was stopped by a gentleman who asked for me. It was Mr. Bancroft, the historian, then a resident of Northhampton. He cordially welcomed us as his guests, and ordered the stage up the hill to his house; such a house! It stood on a lofty terrace, and its balcony overlooked first the garden, then the orchard stretching down the slope, then the delicious village, and the river with its meadows, while opposite rose Mount Holyoke.”

- Bryant, William Cullen, April 24, 1843, describing St. Anastasia, FL, in A Tour in the Old South (quoted in Clarke 1993: 2:161)[25]

- “In another part of the same island, which we visited afterward, is a dwelling-house situated amid orange-groves. Closely planted rows of the sour orange, the native tree of the country, intersect and shelter orchards of the sweet orange, the lemon, and the lime.”

- B., P., January 1844, “Progress of Horticulture in Rochester, N.Y.,” describing residence of John Robert Murray, Mount Morris, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 10: 18)

- “The orchard contains between thirty and forty varieties of well selected pears, an equal number of peach of which over one hundred and fifty trees have borne the past season; among them are five seedlings, raised by J.R. Murray, Esq., senior, said to be superior fruit; ten varieties of plum, eight of cherry, five of apricot and five of nectarine; in all six or eight acres devoted to the culture of fruits.”

- O’Conner, Rachel, 1844, in a letter to William F. Weeks, describing Evergreen Plantation, estate of Rachel O’Connor, Bayou Sarah, LA (quoted in Turner 1993: 495)[26]

- “[24 February] I have my orchard planted with better than four hundred young fruit trees. I did not think I had so many friends. The people sent me trees from all quarters untill [sic] the ground was filled. It adds much to the beauty of the place. . . .

- “[23 March] My new orchard is my idol. I am afraid I think too much of it, & that God will punish me for letting my heart cling to earthly treasures. I am not afraid to love the little black children. Christ suffered on the cross for us all.”

- Hovey, C. M., December 1846, “Notes of a Visit to several Gardens in the Vicinity of Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York,” describing the garden of H. N. Langworthy, near Rochester, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 14: 529–30)[27]

- “One orchard planted with alternate rows of the Early York and Early Crawford, had this year just begun to bear, producing specimens of the latter, which quickly sold at five dollars per bushel; the Early York is a very early and profitable peach; the trees vigorous, healthy and abundant bearers: this is the Early York, figured in our Fruits of America, with serrate leaves. The ground is manured and ploughed the first year after the trees are planted; the next year, it is sown to clover, which is turned in as a green crop; this, with a light application of manure, is repeated every year. The trees are thus kept in a vigorous growing condition, and we saw no evidence of a yellow peach tree in the whole orchard.

- “The apple orchards, with one or two exceptions, are cultivated in the same manner, that is, manure and a crop of clover every year: pursuing this system, the trees make an exceedingly vigorous growth, and when they begin to bear, are loaded with finest specimens of fruit.”

- Downing, A. J., 1849, describing a suburban villa residence in Burlington, NJ (1849; repr., 1991: 117–18)[28]

- “The house, a, stands quite near the bank of the river, while one front commands fine water views, and the other looks into the lawn or pleasure grounds, b. On one side of the area is the kitchen garden, c, separated and concealed from the lawn by thick groups of evergreen and deciduous trees. At e, is a picturesque orchard, in which the fruit trees are planted in groups instead of straight lines, for the sake of effect.” [Fig. 8]

- Eppes, Francis, c. 1850, describing Eppington, plantation of Francis Eppes, on the James River, VA (quoted in Weaver 1969: 31)[29]

- “. . . and to the right of the lawn, as you entered, was an extensive orchard of the finest fruit, with the stables between, at the corner and on the road. The mansion . . . was almost imbedded in a beautiful double row of the tall Lombardy poplar—the most admired of all trees in the palmy days of old Virginia—and this row reached to another double row or avenue which skirted one side of the lawn, dividing it from the orchard and stables.”

- Committee on the Capitol Square, Richmond City Council, July 26, 1851, describing John Notman’s plans for the Capitol Square, Richmond, VA (quoted in Greiff 1979: 162)[30]

- “The most beautiful feature of the contemplated alterations of the Square, however, will be found in the arrangement of the trees and shrubbery. Instead of planting these in parallel rows, like an ordinary orchard some attention will be paid to landscape gardening—groves, arbours, parterres, and fountains will combine to render the Square a place of delightful resort.”

Citations

- Lawson, William, 1618, A New Orchard and Garden (1618; repr., 1982: 11, 13)[31]

- “The goodnesse of the Soyle, and Site, are necessarie to the well being of an Orchard simplie, but the forme is so far necessarie, as the owner shall think meets for that kinde of forme wherewith every particular man is delighted, we leave it to himselfe, fuumcuig pulchrum. The forme that men like in generall is a square, for although roundnes, be forma perfectissima, yet y principle is good where necessitie by art hath not force forme other forme. And for as much as one principall end of Orchards is recreation by walks, and universallie walks are streight, it followes that the best forme must be square, as best agreeing with streight walks: yet if any man be rather delighted with some other forme, or if the ground will not beare a square, I risceommend not any forme, so it be formall. . . .

- “All your labour past and to come about an Orchard is lost, unlesse you fence well. It that grieve you much to see your young lets rubble ofe at the rootes, the barke pilld, the boughs and twigs cropt, your fruit stolne, your trees broke, and all your many yeares Labours and hopes destroyed, for want of fences.”

- Parkinson, John, 1629, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629; repr., 1975: 535–37)[32]

- “And first, I hold that an Orchard which is, or should bee of some reasonable large extent, should be so placed, that the house should have the Garden of flowers just before it open upon the South, and the Kitchen Garden on the one side thereof, should also have the Orchard on the other side of the Garden of Pleasure, for many good reasons: First, for that the fruit trees being grown great and tall, will be a great shelter from the North and East windes, which may offend your chiefest Garden, and although that your Orchard stand a little bleake upon the windes, yet trees rather endure these strong bitter blasts, then other smaller and more tender shrubs and herbes can doe. Secondly, if your Orchard should stand behinde your Garden of flowers more Southward, it would shadow too much of the Garden, and besides, would so binde in the North and East, and North and West windes upon the Garden, that it would spoile many tender things therein, and so much abate the edge of your pleasure thereof, that you would willingly wish to have no Orchard, rather then that it should so much annoy you by the so ill standing thereof. Thirdly, the falling leaves being still blowne with the winde so aboundantly into the Garden, would either spoile many things, or have one daily and continuall attending thereon, to cleanse and sweepe them away. Or else to avoide these great inconveniences, appoint out an Orchard the farther off, and set a greater distance of ground betweene. . . .

- “According to the situation of mens grounds, so must the plantation of them of necessitie be also; and if the ground be in forme, you shall have a formall Orchard: if otherwise, it can have little grace or forme. And indeed in the elder ages there was small care or heede taken for the formality; for every tree for the most part was planted without order, even where the master or keeper found a vacant place to plant them in, so that oftentimes the ill placing of trees without sufficient space betweene them, and negligence in not looking to uphold them, procured more waste and spoile of fruit, then any accident of winde or weather could doe. Orchards in most places have not bricke or stone wals to secure them, because the extent thereof being larger then of a Garden, would require more cost, which every one cannot undergoe; and therefore mud wals, or at the best a quicke set hedge, is the ordinary and most usuall defence it findeth almost in all places: but with those that are of ability to compasse it with bricke or stone wals, the gaining of ground, and profit of the fruit trees, planted there against, will in short time recompense that charge. . . . Having an Orchard containing one acre of ground, two, three, or more, or lesse, walled about, you may so order it, by leaving a broad and large walke betweene the wall and it, . . . and by compassing your Orchard on the inside with a hedge (wherein may bee planted all sorts of low shrubs or bushes . . .) therefore to describe you the modell of an Orchard, both rare for comelinesse in the proportion, and pleasing for the profitablenesse in the use, and also durable for continuance, regard this figure is here placed for your direction, where you must observe, that your trees are here set in such an equall distance one from another every way, & as is fittest for them, that when they are grown great, the greater branches shall not gall or rubbe one against another; for which purpose twenty or sixteene foot is the least to be allowed for the distance every way of your trees, & being set in rowes every one in the middle distance, will be the most graceful for the plantation, and besides, give you way sufficient to passe through them, to pruine, loppe, or dresse them, as need shall require, and may also bee brought (if you please) to that grace-full delight, that every alley or distance may be formed like an arch, the branches of either side meeting to be enterlaced together.”

- La Quintinie, Jean de, 1693, “Dictionary,” The Compleat Gard’ner (1693; repr., 1982: n.p.)[33]

- “Gardens are choice inclosed pieces of Ground planted with Edible Plants, Fruit-Trees, and Flowers, and differ from Orchards, which are commonly planted with Standard Fruit-Trees, and are seldom walled, or so curiously inclosed as Gardens. . . .

- “Orchards, or Hort-yards Ort-yards, are inclosed pieces of Ground planted chiefly with Standards Fruit-Trees, and more often fenced with Hedges, or Ditches, and other fences than with Walls.”

- Bradley, Richard, 1720, New Improvements of Planting and Gardening (1720: 2.3: 27)[34]

- “There are two Ways of Planting an Orchard; the one to make it entirely for Fruit, the other to plant the Trees at such distances as to admit of an Under-crop. I must confess, was I to make an Orchard to please my self, I would first divide the Ground into parcels, allowing handsome Walks between them, which should some of them be fenced on the Sides with Espaliers of Fruit, others left open with Borders only on their Sides, adorn’d with Rows of Standard-Apples. . . .

- “In these several Quarters plant your Trees at about sixteen Foot distance, if you design a close Orchard, or near thirty Foot asunder if the Ground is design’d for Beans, Peas, or such like Under-crops.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1743, Cyclopaedia (1743: 2:n.p.)[35]

- “ORCHARD, a seminary or plantation of fruit trees, chiefly apples and pears. See FRUIT-tree.

- “It is a rule among gardeners, that those orchards, caeteris paribus, thrive best, which lie open to the south, south-west, and south-east; and are screened from the north: the soil dry, and deep. See EXPOSURE.

- “Orchards are stocked by transplantation; seldom by semination.”

- Miller, Philip, 1754, The Gardeners Dictionary (1754; repr., 1969: 977–78)[36]

- “ORCHARD. In planting of an Orchard, great Care should be had of the Nature of the Soil, that such Sorts of Fruit as are adapted to grow upon the Ground intended to be planted, may be chosen. . . .

- “As to the Position of the Orchard (if you are at full Liberty to choose), a rising Ground, open to the South-east is to be preferr’d . . . where the Rise [of a hill] is gentle, it is of great Advantage to the Trees by admitting the Sun and Air between them better than it can upon an intire [sic] Level. . . .

- “You should also have a great regard to the Distance of planting the Trees, which is what few People have rightly consider’d; for if you plant them too close, they will be liable to Blights; and the Air hereby pent in amongst them, will cause the Fruit to be ill-tasted. . . .

- “Wherefore I can’t but recommend the Method which has been lately practised by some particular Gentlemen with very good Success; and that is, to plant the Trees fourscore Feet asunder, but not in regular Rows. The Ground between the Trees they plow and sow with Wheat, and other Crops, in the same manner as if it were clear from Trees; and they observe their Crops to be full as good as those quite exposed.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 2:n.p.)[37]

- “O’RCHARD. n.s. [either hortyard or wortyard, says Skinner . . . Saxon. Junius.] A garden of fruit-trees.”

- Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce, 1769, The Complete Farmer (1769: n.p.)[38]

- “ORCHARD. . . .

- “for a family only, it is hardly worth while to plant an orchard; since a kitchen-garden well planted with espaliers will afford more fruit than can be eaten while good, especially if the kitchen-garden be proportioned to the largeness of the family: and if cyder be required, there may be a large avenue of apple-trees extended cross a neighbouring field, which will render it pleasant, and produce a great quantity of fruit; or there may be some single rows of trees planted to surround the fields, &c. which will fully answer the same purpose, and be less liable to the fire-blasts before-mentioned.”

- Deane, Samuel, 1790, The New-England Farmer (1790: 188–89, 197–98)[39]

- “NURSERY. . . .

- “In this situation they are to grow till they are transplanted into orchards, &c. . . . Trees to be transplanted into forests, may be cultivated in a nursery in the same manner as fruit trees. . . .

- “ORCHARD, a plantation of fruit-trees, not again to be removed.

- “An orchard may consist wholly of pear-trees; or of quince, peach, plum, &c. or it may be a mixture of various kinds of trees. But orchards of apple-trees are almost the only ones in this country. Other fruit-trees are commonly planted in the borders of fields, or gardens; because only a small number of them is desired. . . .

- “Plains, hollows, or high summits, are not so good situations for orchards, as land gently sloping: And a south-eastern exposure is generally the best. . . .

- “Concerning the right distance of the trees, there are a variety of opinions. But the coldness and wetness of the climate, an argument used in England for placing them far asunder, does not apply in this country. It should be considered at the time of planting, to what size the trees are likely to grow: And they should be set so far asunder, that their limbs will not be likely to interfere with each other when they arrive to their full growth. . . . Twenty five feet may be the right distance in some soils; but thirty five feet will not be too much in the best, or even forty. . . .

- “An orchard must be constantly well fenced, to keep out cattle. It should be enclosed by itself. . . .

- “After an orchard is planted, it is best to keep the land continually in tillage, till the trees have nearly got their full growth. The trees will grow faster, and be more fruitful.”

- Anonymous, 1798, Encyclopaedia (1798: 13:471–72)[40]

- “ORCHARD, a garden-department, configured entirely to the growth of standard fruit trees, for furnishing a large supply of the most useful kinds of fruit.

- “In the orchard you may have, as standards, all sorts of apple-trees, most sorts of pears and plums, and all sorts of cherries. . . . But to have a complete orchard you may also have quinces, medlars, mulberries; service trees, filberts, Spanish nuts, berberries; likewise walnuts and chesnuts; which two latter are particularly applicable for the boundaries of orchards, to screen the other trees from the insults of impetuous winds and cold blasts. All the trees ought to be arranged in rows from 20 to 30 feet distance, as hereafter directed. . . .

- “A general orchard, however composed of all the beforementioned fruit-trees, should consist of a double portion of apple-trees or more, because they are considerably the most useful fruit, and may be continued for use the year round.

- “The utility of a general orchard, both for private use and profit, stored with the various sorts of fruit-trees, must be very great, as well as afford infinite pleasure from the delightful appearance it makes from early spring till late in autumn: In spring the various trees in blossom are highly ornamental; in summer, the pleasure is heightened by observing the various fruits advancing to perfection; and as the season advances, the mature growth of the different species arriving to perfection in regular succession, from May or June, until the end of October, must afford exceding delight, as well as great profit. . . .

- “With respect to the situation and aspect for an orchard, we may observe very thriving orchards both in low and high situations, and on declivities and plains, in various aspects or exposures, provided the natural soil is good; we should, however, avoid very low damp situations as much as the nature of the place will admit.”

- Marshall, Charles, 1799, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening (1799: 1:43–45)[41]

- “AN ORCHARD may be spoken of here; i. e. a spot to plant standard trees in, which are forbidden a place in the garden; but it must not be a small spot. . . .

- “The trees being planted, at proper distances, the ground may be kept under some sort of crops, for several years to come, with proper dressing. . . .

- “On this subject, it may not be amiss to give the instructions of one of our best gardeners.

- “It is an error (says he) to let turf cover the surface of the ground in an orchard. The trees should be at such distances, that a plough may go between them, and in that case the trees thrive every way better.”

- Bordley, J. B., 1801, Essays and Notes on Husbandry and Rural Affairs (1801: 74–75)[42]

- “The homestead includes this yard; together with its stackyard, the garden, nursery, orchard, and some acres of grass; enough for occasionally letting mares, or sick beasts run on, at liberty.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (1806: 38)[43]

- “THE Orchard is a department consigned entirely to the growth of standard fruit-trees, for furnishing a large supply of the most useful kinds of fruit; in which you may have as standards, apple, pear, plum, cherry, peach, apricot, quince, almond, and nectarine trees. . . .

- “But sometimes, Orchards consist entirely of apple trees. . ..

- “The utility of a general Orchard, or Orchards, both for private use and profit, stored with the various sorts of fruit-trees, must be very great; as well as afford infinite pleasure from the delightful appearance it makes from early spring, until late in autumn.”

- Gregory, G., 1816, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1816: 2:n.p.)[44]

- “ORCHARD, a plantation of fruit-trees. In planting an orchard great care should be taken that the soil is suitable to the trees planted in it; and that they are procured from a soil nearly of the same kind, or rather poorer than that laid out for an orchard. As to the situation, an easy rising ground, open to the south-east, is to be preferred. Mr. Miller recommends planting the trees fourscore feet asunder, but not in regular rows and would have the ground between the trees plowed and sown with wheat and other crops, in the same manner as if it was clear from trees; by which means the trees will be more vigorous and healthy, will abide much longer, and produce better fruit.”

- Abercrombie, John, with James Mean, 1817, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener (1817: 180)[45]

- “AN orchard is a plantation of standard fruit-trees which in general have stems high enough to keep the boughs, leaves, and fruit, from the reach of cattle; but where cattle are excluded, dwarf and half-standards may occupy two rows next to the sunny side.”

- Coxe, William, 1817, A View of the Cultivation of Fruit Trees, and the Management of Orchards and Cider (1817: 30, 33–34)[46]

- “ON THE SITUATION OF ORCHARDS.

- “A south east aspect, which admits the influence of the early morning Sun, and is protected from the pernicious effects of northerly winds, will be found the best site for an orchard. The situation should be neither too high nor too low. . . .

- “ON THE PLANTING AND CULTIVATION OF ORCHARDS.

- “The first thing to be determined upon in the planting of an orchard, is the proper distance of the trees: if a mere fruit plantation be the object, the distance may be small—if the cultivation of grain and grass be in view, the space between the trees must be wider: at thirty feet apart, an acre will contain forty-eight trees. . . . it will probably be found, that forty feet is the most eligible distance for a farm orchard.—It will admit sufficient sun and air, in our dry and warm climate; and until the trees shall be fully grown, will allow of a profitable application of the ground to the cultivation of grain and grass.”

- Thacher, James, 1822, The American Orchardist (1822: 10–11)[47]

- “It must be confessed, as a notorious truth, that an orchard, planted and cultivated in the most advantageous manner in point of beauty, profit, and convenience, is scarcely to be found in the sphere of our observation. The most palpable neglect prevails in respect of proper pruning, cleaning, and manuring round the roots of trees, and of perpetuating choice fruit, by engrafting from it on other stocks. Old orchards are, in general, in a state of rapid decay; and it is not uncommon to see valuable and thrifty trees exposed to the depredations of cattle and sheep, and their foliage annoyed by caterpillars and other destructive insects. In fact, we know of no branch of agriculture so unaccountably and so culpably disregarded. . . . It may, with propriety, be affirmed, that a judiciously-cultivated orchard of select fruit, if situated at a convenient distance from a large town or village, would yield an annual profit equal to any production of the industrious husbandman. . . .

- “In every rural establishment, a fruit orchard should be considered an indispensable appendage, as a source of real emolument, and as contributing to health, pleasure, and recreation. It will be conceded, that, in the whole department of rural economy, there is not a more noble, interesting, and beautiful exhibition, than a fruit orchard, systematically arranged, while clothed with nature’s foliage, and decorated with variegated blossoms perfuming the air, or when bending under a load of ripe fruit of many varieties. It is among the excellences of a fruit orchard, that it affords a salubrious beverage, an adequate supply of which would have a happy tendency to diminish, if not supersede, the consumption of ardent spirits, so destructive to the health and moral character of our citizens.”

- Loudon, J. C., 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 105, 451, 482)[48]

- “482. . . .

- “The first work after a settlement [in North America] is to plant a peach and apple orchard, placing the trees alternately. The peach, being short-lived, is soon removed, and its place covered by the branches of the apple-trees. . . .

- “2355. To unite the agreeable with the useful is an object common to all the departments of gardening. The kitchen-garden, the orchard, the nursery, and the forest, are all intended as scenes of recreation and visual enjoyment, as well as of useful culture; and enjoyment is the avowed object of the flower-garden, shrubbery, and pleasure-ground. . . .

- “2527. An orchard, or separate plantation of the hardier fruit-trees is a common appendage to the kitchen-garden, where that department is small, or does not contain an adequate number of fruit-trees to supply the contemplated demand of the family. Sometimes this scene adjoins the garden, and forms a part of the slip; at other times it forms a detached, and, perhaps, distant enclosure, and not unfrequently, in countries where the soil is propitious to fruit-trees, they are distributed in the lawn, or in a scene, or field kept in pasture. Sometimes the same object is effected by mixing fruit-trees in the plantations near the garden and house.”

- Parmentier, André, 1828, The New American Gardener (1828: 186)[49]

- “The apple-tree alone, on account of its horizontal branches, should be confined to the orchard, where its useful products are ornamental and valuable.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[50]

- “OR’CHARD, n. [Sax. ortgeard; Goth. aurtigards; Dan. urtegaard; Sw. ortegard; that is, wort-yard, a yard for herbs. The Germans call it baumgarten, tree-garden, and the Dutch boomgaard, tree-yard. See Yard.]

- “An inclosure for fruit trees. In Great Britain, a department of the garden appropriated to fruit trees of all kinds, but chiefly to apples trees. In America, any piece of land set with apple trees, is called an orchard; and orchards are usually cultivated land, being either grounds for mowing or tillage. In some parts of the country, a piece of ground planted with peach trees is called a peach-orchard. But in most cases, I believe the orchard in both countries is distinct from the garden.”

- Fessenden, Thomas Green, 1833, The New American Gardener (1833: 220–22)[51]

- “ORCHARD.—Soil.—Any soil is suitable for an orchard, which produces good crops of grain, grass, or garden vegetables; but a good, deep, sandy loam, not too dry, nor very moist, is to be preferred. In the stiffest part of the ground, you may plant pear-trees; in the lighter, apples, plums, and cherries; and, in the lightest, peach, nectarine, and apricots.

- “Aspect.—A south-eastern aspect is generally recommended; but, when this exposes the trees to the sea winds, a south-western may be better. Some recommend a northern aspect, and planting trees the north side of a wall, to prevent them from budding and blowing so early in the spring as to expose them to frosts. . . .

- “Distance of trees in an orchard.—‘It should be considered, at the time of planting, to what size the trees are likely to grow. And they should be set so far asunder, that their limbs will not be likely to interfere with each other, when they arrive at full growth. In a soil that suits them best they will become largest. Twenty-five feet may be the right distance in some soils; but thirty-five feet will not be too much in the best, or even forty.’—Deane.

- “Cropping.—‘It is proper to crop the ground among new-planted orchard-trees, for a few years, in order to defray the expense of hoeing and cultivating it; which should be done until the temporary plants are removed, and the whole be sown down to grass. But it is by no means advisable to carry the system of cropping with vegetables to such an excess as is frequently done. If the bare expense of cultivating the ground, and the rent, be paid, by such cropping, it should be considered enough. As the trees begin to produce fruit, begin also to relinquish cropping. When by their productions they defray all expenses, crop no longer. I consider these as being wholesome rules, both for the trees and their owners.’—Loudon

- “Orchards which are laid down to grass last longest; but it is necessary to keep the ground clear of weeds and grass, for some little distance from the roots.”

- Anonymous, December 17, 1834, “Orchards Around Farm Houses” (New England Farmer 13: 181)

- “It is expedient that every farm should have some portion of orchard ground attached to it. The most convenient and guarded situation for it is immediately behind the house, so that the back kitchen door may open into it. . . . The most profitable kind of orchard is that which contains all kinds of hardy fruit trees and bushes, and where the land is solely appropriated to that purpose. This kind resembles gardening more than farming, and is therefore unsuitable to large farms, but quite applicable to small ones, to which an acre of orchard, requiring no horse labor, would be of essential benefit. In such orchards, half standard apples are planted in rows eighteen feet from each other, the trees being twelve feet apart. In the same line with the apple trees are planted either gooseberries or currant bushes, or what sometimes pay equally well, filberts.”

- Sayers, Edward, September 1835, “The Apple Orchard” (American Gardeners’ Magazine 1: 330)

- “The constructing of rail-roads, canals and public thoroughfares, also deter, in a measure, the formation of the apple orchard in almost all parts of the country, which will be seen by observation. Many trees are also cut down, owing to old age, and many for fire-wood and other purposes of domestic use; but few young trees are planted at the present day, to fill up the deficiency of those decaying, and yearly dwindling away, which, in time, must prove, that scarcity will be the result in general, especially if the crops are light.”

- Hooper, Edward James, 1842, The Practical Farmer, Gardener and Housewife (1842: 11, 279)[52]

- “When put in an orchard they should be 6 or 7 feet high; 30 feet each way is the proper distance apart in the orchard. The mode should be thus, [illus.] or quincunx form which is best for close room. . . .

- “ORCHARD. Orchards are the parts of a farm appropriated to the growth of standard fruit trees. They may be reckoned among the permanent improvements of a farm, and should be kept in view in its first management and laying out.”

- Downing, A. J., 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849; repr., 1991: 115–17)[53]

- “Figure 25 is the plan of an American mansion of considerable extent, only part of the farm lands, l, being here delineated. In this residence, as there is no extensive view worth preserving beyond the bounds of the estate, the pleasure grounds are surrounded by an irregular and picturesque belt of wood. . . . The small arabesque beds near the house are filled with masses of choice flowering shrubs and plants; the kitchen garden is shown at d, and the orchard at e.” [Fig. 9]

- Downing, A. J., July 1851, “A Few Words on Fruit Culture” (Horticulturist 6: 297–98)

- “Within the last five years, the planting of orchards has, in the United States, been carried to an extent never known before. In the northern half of the Union, apple trees, in orchards, have been planted by thousands and hundreds of thousands, in almost every state. The rapid communication established by means of railroads and steamboats in all parts of the country, has operated most favorably on all the lighter branches of agriculture, and so many farmers have found their orchards the most profitable, because least expensive part of their farms, that orcharding has become in some parts of the west, almost an absolute distinct species of husbandry.”

Images

Inscribed

Batty Langley, “An Improvement of a beautiful Garden at Twickenham,” in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. IX.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Sketch of the Estate of Henry Banks Esqr. on York River, March 1797.

J. B. Bordley, Plan of a Farmyard, with details in section, in J. B. Bordley, Essays and Notes on Husbandry and Rural Affairs (1801), pl. I.

Thomas Jefferson, “Plan of Spring Roundabout at Monticello,” c. 1804.

Thomas Jefferson, Plan of the grounds at Monticello, 1806.

Charles Willson Peale, Sketches of Belfield, 1810.

Anonymous, “Plan of a Mansion Residence, laid out in the natural style,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 115, fig. 25. The “orchard” is indicated at “e.”

Anonymous, “Plan of a Suburban Villa Residence,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 118, fig. 26. Downing notes that “At e, is a picturesque orchard.”

Anonymous, “Plan of the foregoing grounds as a Country Seat, after ten years’ improvement,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 114, fig. 24.

Anonymous, “View of a Picturesque farm (ferme ornée),” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 120, fig. 27.

Associated

Edward Penington (artist), William Fletcher Boogher (publisher), “A description of two lotts in the city of Philadelphia, the one belonging to the Proprietary, William Penn, the other to his daughter, Lætitia Penn, together with the streets & lotts bounding them. Drawn this 23d day of the 12th month 1698 by Edward Penington, Surv. Genll” [detail], 1882 facsimile.

George Washington, A Plan of My Farm on Little Huntg. Creek & Potomk R., 1766.

Thomas Jefferson, Monticello: orchard and vineyard (plat), c. 1778.

Attributed

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Section of the northern course of the canal from the tide in the Elk River at Frenchtown to the forked [oak] in Mr. Rudulph’s swamp, 1803.

Notes

- ↑ When J. C. Loudon listed works on gardening published in North America, he cited three texts that were concerned with trees and orchards, including Humphrey Marshall’s Arbustrum Americanum (1785), view on Zotero, and William Coxe’s A View of the Cultivation of Fruit Trees, with the Management of Orchards and Cider (1817), view on Zotero. The citations gathered here come primarily from treatises devoted to ornamental landscape design, as opposed to that of husbandry. Agricultural aspects of orchards, therefore, are not addressed fully here. Nonetheless, a substantial amount of literature on this latter topic was produced in the period c. 1600–1850.

- ↑ See Gordon P. De Wolf Jr., “Andrew Jackson Downing and Pomology,” in Prophet with Honor: The Career of Andrew Jackson Downing, 1815–1852 (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1989), 125–52, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For George Washington’s description of this fruit garden, see the diary entries in Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, eds., The Diaries of George Washington, vol 4 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1978), 274, view on Zotero. Dennis Pogue, “Archaeological Investigations at the ‘Vineyard Inclosure’ Mount Vernon Plantation, Mount Vernon, Virginia,” File Report 3 (Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, Mount Vernon, VA, March 1992), 45–49, contains an analysis of the archaeological remains of Washington’s fruit garden.

- ↑ Perry Miller and Thomas H. Johnson, eds., The Puritans, 2 vols. (New York: Harper and Row, 1963), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Hedrick 1988, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Blome, The Present State of His Majesties Isles and Territories in America (London: H. Clark, 1687), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Louis B. Wright and Marion Tinling, eds., The Secret Diary of William Byrd of Westover, 1709–1712 (New York: Arno Press, 1972), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Eliza Lucas Pinckney, The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 1739–1762, ed. Elise Pinckney (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Philip Vickers Fithian, Journal & Letters of Philip Vickers Fithian, 1773–1774: A Plantation Tutor of the Old Dominion, ed. Hunter D. Farish (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg, 1943), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Anburey, Travels through the Interior Parts of America, 2 vols. (1789; repr., New York: New York Times and Arno Press, 1969), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Alice B. Lockwood, ed., Gardens of Colony and State: Gardens and Gardeners of the American Colonies and of the Republic before 1840, 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s for the Garden Club of America, 1931), view on Zotero. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Lockwood" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels in New England and New York, 4 vols. (New Haven, Conn.: Timothy Dwight, 1821), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Parkinson, A Tour in America, 1798, 1799, and 1800: Exhibiting Sketches of Society and Manners, and a Particular Account of the American System of Agriculture, with Its Recent Improvements, 2 vols. (London: J. Harding, 1805), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John C. Ogden, An Excursion into Bethlehem & Nazareth, in Pennsylvania, in the Year 1799 (Philadelphia: Charles Cist, 1800), view on Zotero.

- ↑ François André Michaux, Travels to the West of the Alleghany Mountains, in the States of Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessea, and back to Charleston, by the Upper Carolines . . . Undertaken, in the Year 1802, 2nd ed. (London: B. Crosby & Co. and J. F. Hughes, 1805), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Parker Cutler, Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D. (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Drayton, “The Diary of Charles Drayton I, 1806,” Drayton Papers, MS 0152, Drayton Hall, SC, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Katharine M. Jones, The Plantation South (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1957), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Cobbett, A Year’s Residence in the United States of America (London: Sherwood, Neely and Jones, 1819), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thaddeus William Harris, A Discourse Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on the Celebration of Its Fourth Anniversary, October 3, 1832 (Cambridge, MA: E. W. Metcalf, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Cullen Bryant, The Letters of William Cullen Bryant, ed. William Cullen II Bryant and Thomas G. Voss (New York: Fordham University Press, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Harriet Martineau, Retrospect of Western Travel, 2 vols. (London: Saunders and Otley, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Graham Clarke, ed., The American Landscape: Literary Sources and Documents, 3 vols. (East Sussex, England: Helm Information, 1993), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Suzanne Turner, Historic Landscape Report: The Landscape at the Shadows-on-the-Teche (New Iberia, LA: Shadows-on-the-Teche, 1993), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes of a Visit to Several Gardens in the Vicinity of Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, in October, 1845,” The Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 12 (1846): 241–48, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bettie Woodson Weaver, “Mary Jefferson and Eppington,” Virginia Cavalcade 19 (1969): 30–38, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constance Greiff, John Notman, Architect, 1810–1865 (Philadelphia: Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1979), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Lawson, A New Orchard and Garden . . . with the Country Housewifes Garden (1618; repr., New York: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (Norwood, NJ: W. J. Johnson, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jean de La Quintinie, The Compleat Gard’ner, or Directions for Cultivating and Right Ordering of Fruit-Gardens and Kitchen Gardens, trans. John Evelyn (New York: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Bradley, New Improvements of Planting and Gardening, Both Philosophical and Practical . . ., 3rd ed., 2 vols. (London: W. Mears, 1719), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . ., 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741–43), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Philip Miller, The Gardeners Dictionary (1754; repr., New York: Verlag Von J. Cramer, 1969), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce, The Complete Farmer, or A General Dictionary of Husbandry, 2nd ed. (London: R. Baldwin et al., 1769), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Deane, The New-England Farmer, or Georgical Dictionary (Worcester, MA: Isaiah Thomas, 1790), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, Encyclopaedia, or A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature, 18 vols. (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1798), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Marshall, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening, 1st American ed., 2 vols. (Boston: Samuel Etheridge, 1799), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. B. [John Beale] Bordley, Essays and Notes on Husbandry and Rural Affairs, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1801), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M’Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done . . . for Every Month of the Year . . . (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Gregory, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 1st American ed.. 3 vols. (Philadelphia: Isaac Peirce, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Abercrombie, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener Or, Improved System of Modern Horticulture (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1817), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Coxe, A View of the Cultivation of Fruit Trees, and the Management of Orchards and Cider (Philadelphia: M. Careyard, 1817), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Thacher, The American Orchardist; Or, A Practical Treatise on the Culture and Management of Apple and Other Fruit Trees . . . (Boston: Joseph W. Ingraham, 1822), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ André Parmentier, “The Art of Landscape Gardening,” in The New American Gardener, ed. Thomas Fessenden (Boston: J. B. Russell, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Fessenden, The New American Gardener, 7th ed. (Boston: Russell, Odiorne, 1833), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward James Hooper, The Practical Farmer, Gardener and Housewife, or Dictionary of Agriculture, Horticulture, and Domestic Economy (Cincinnati, OH: George Conclin, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., 1991: Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.