Difference between revisions of "Public garden/Public ground"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

As cities grew larger and more densely populated, citizens sought refuge outside the urban center, seeking “a breathing place to a thickly inhabited city,” as one observer wrote in 1835. In lieu of [[park]]s, many colonial estates were transformed into public [[pleasure garden]]s, taking advantage of the fine stock of plants that had been cultivated in older private gardens. The 18th-century country [[seat]] [[Lemon Hill]] in Philadelphia [Fig. 10], for example, was turned into a commercial public garden in the 1830s. | As cities grew larger and more densely populated, citizens sought refuge outside the urban center, seeking “a breathing place to a thickly inhabited city,” as one observer wrote in 1835. In lieu of [[park]]s, many colonial estates were transformed into public [[pleasure garden]]s, taking advantage of the fine stock of plants that had been cultivated in older private gardens. The 18th-century country [[seat]] [[Lemon Hill]] in Philadelphia [Fig. 10], for example, was turned into a commercial public garden in the 1830s. | ||

| − | A tension often existed between the marketing of the public gardens as a moral, salubrious “breathing place” and its competing financial goals. The advertising for commercial public gardens promoted them as places of rational amusement, wholesome air, and public taste. In practice, however, the ice cream, slide show, and musical entertainments drew in larger crowds than did the promise of an uplifting, educative environment. Occasionally the term “public garden” was used to refer to a commercial [[nursery]] open to the public. That was the case at the McAran Botanic Garden and Nursery in Philadelphia [<span id="Fig_11_cite"></span>[[#Fig_11|See Fig.11]]], which was operated by the former gardener of [[The Woodlands]] and [[Lemon Hill]], two of the most important gardens of the colonial period. His horticultural business also profited from added entertainments, such as a menagerie and the pastries that were offered for sale. | + | A tension often existed between the marketing of the public gardens as a moral, salubrious “breathing place” and its competing financial goals. The advertising for commercial public gardens promoted them as places of rational amusement, wholesome air, and public taste. In practice, however, the ice cream, slide show, and musical entertainments drew in larger crowds than did the promise of an uplifting, educative environment. Occasionally the term “public garden” was used to refer to a commercial [[nursery]] open to the public. That was the case at the McAran Botanic Garden and Nursery in Philadelphia [<span id="Fig_11_cite"></span>[[#Fig_11|See Fig. 11]]], which was operated by the former gardener of [[The Woodlands]] and [[Lemon Hill]], two of the most important gardens of the colonial period. His horticultural business also profited from added entertainments, such as a menagerie and the pastries that were offered for sale. |

—''Therese O'Malley'' | —''Therese O'Malley'' | ||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

| − | <div id="Fig_11"></div>[[File:1193.jpg|thumb|Fig. 11, David J. Kennedy, ''McAran’s Garden'', 1840. [#Fig_11_cite|back up to History]]] | + | <div id="Fig_11"></div>[[File:1193.jpg|thumb|Fig. 11, David J. Kennedy, ''McAran’s Garden'', 1840. [[#Fig_11_cite|back up to History]]]] |

*Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1830, describing the McAran Botanic Garden and Nursery, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Boyd 1929: 433)<ref>James Boyd, ''A History of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1827–1927'' (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1929), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/UN9TRH8T view on Zotero].</ref> | *Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1830, describing the McAran Botanic Garden and Nursery, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Boyd 1929: 433)<ref>James Boyd, ''A History of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1827–1927'' (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1929), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/UN9TRH8T view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

:“It contains 6 acres, and is the largest '''public garden''' about the city. Here may be seen part of the celebrated collection of plants that formerly belonged to William Hamilton, of [[the Woodlands]], and now the property of Mr. D’Arras [McAran].” [Fig. 11] | :“It contains 6 acres, and is the largest '''public garden''' about the city. Here may be seen part of the celebrated collection of plants that formerly belonged to William Hamilton, of [[the Woodlands]], and now the property of Mr. D’Arras [McAran].” [Fig. 11] | ||

| Line 118: | Line 118: | ||

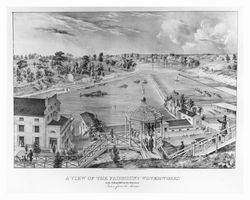

| − | [[File:0541.jpg|thumb|Fig. | + | [[File:0541.jpg|thumb|Fig. 12, John T. Bowen, ''A View of the Fairmount Water-Works with Schuylkill in the distance, taken from the [[Mount]]'', 1838.]] |

*Dickens, Charles, 1842, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (1842: 122)<ref>Charles Dickens, ''American Notes'' (Paris: Baudry’s European Library, 1842), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TTQMJ9AD view on Zotero].</ref> | *Dickens, Charles, 1842, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (1842: 122)<ref>Charles Dickens, ''American Notes'' (Paris: Baudry’s European Library, 1842), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TTQMJ9AD view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

:“Philadelphia is most bountifully provided with fresh water, which is showered and jerked about, and turned on, and poured off, everywhere. The Waterworks, which are on a height near the city, are no less ornamental than useful, being tastefully laid out as a '''public garden''', and kept in the best and neatest order.” [Fig. 13] | :“Philadelphia is most bountifully provided with fresh water, which is showered and jerked about, and turned on, and poured off, everywhere. The Waterworks, which are on a height near the city, are no less ornamental than useful, being tastefully laid out as a '''public garden''', and kept in the best and neatest order.” [Fig. 13] | ||

Revision as of 14:54, January 23, 2020

(Publick garden)

History

J. C. Loudon's 1834 definition of the public garden neatly covers the history of these spaces in the colonial and federal period: the feature served recreational, educational, and commercial functions. Whether publicly or privately owned, the public garden was a space made available to the general populace. The public garden, or public ground, phrases used synonymously, could be privately owned with access regulated by race, gender, and price, as was the case at Contoit’s Garden [Fig. 1] and Castle Garden in New York, and the Pagoda and Labyrinth Garden in Philadelphia [Fig. 2]. The government-owned public garden or public ground was land that had been removed from the real estate market. For this kind of public garden, the government determined who had access to public property and under what conditions. For example, when Castle Garden [Fig. 3] was turned over to the city, its interior was planted with flowers and shrubs; later, public baths were added (see Bath). The national Mall in Washington, DC, was the quintessential example of the public garden, as seen in an idealized view of the A. J. Downing plan from 1852 [Fig. 4]. As a symbol of democratic process, the Mall has served since its inception in 1791 as the seat of public celebration, as well as a place of public garden/public ground public protest. Common property, yet another version of public ground, was land to which all members of a community had unrestricted access, as was the case with the vernacular public garden or the unstructured playground.[1]

Although the great age of public parks in America did not begin until after the mid-19th century, there were numerous early examples of the ornamentation of public space and the dedication of open ground for use by the citizenry. Several early town plans had public squares or gardens incorporated into the street plan. The green in New Haven, Connecticut [Fig. 5], the public circle in Annapolis, Maryland, the palace green in Williamsburg, Virginia, and the city of Savannah, Georgia, are examples of 17th- and 18th-century town plans that featured public gardens and public grounds in their original designs.

Philadelphia, laid out in 1682 [Fig. 6], was the site of some of the earliest public gardens, dating from William Penn’s original conception for a “Green Countrie Towne,” which provided five squares kept open for public use. In 1732 the City Assembly of Philadelphia first discussed creating a new public garden by leveling the area behind the city’s State House, the colonial seat of the Pennsylvania colony, and enclosing it “in order that Walks be laid out, and Trees planted to render the same more beautiful and commodious.” It was to “remain a public open green and walks forever.”[2] Like many public gardens, the State House Yard derived its significance from its proximity to an important public building. Numerous images, particularly in prints, were circulated that depicted public gardens surrounding city halls, historic sites, churches, and civic monuments. In some cases, the view or prospect influenced the siting of a public garden. Castle Garden and the battery in Charleston, South Carolina, were both situated at the water’s edge, providing views of the harbor. In other cases, public gardens were located at sites that were already known as popular informal gathering places. In this way, authorities transformed uncontrolled public assembly places into controlled, “improved” open spaces.

An important public ground in New England was the Boston Common, which was set aside as a community property in 1640 (see Common and Square). It was repeatedly improved and ornamented as a public garden. The development of Boston Common followed a typical pattern: open public space that had been used as military training grounds or grazing land in the 17th and early 18th centuries was ceded and transformed into a public garden.[3] This was also true of areas that had previously been used as meeting house lots. Charles Hubbard’s view of Boston Common depicts several of the traditional uses of a public ground, including promenading and military training and display [Fig. 7]. In 1834, a landscaped park, which was designated as the Public Garden, was added to the Common [Fig. 8].

Following the American Revolution, the improvement and ornamentation of public spaces increased with a frequency that amounted to a beautification campaign.[4] Plans for Washington, DC, have included public gardens since the founding of the new federal capital in 1791. The national Mall, which was described as “public walks” on Thomas Jefferson’s sketch of that year [Fig. 9], was sited at the ceremonial and legislative center of the city. Its purpose, to provide a symbolic public space at the center of the federal capital, was reaffirmed with each successive design. In 1832, Congress rejected a proposal to turn over the public gardens of the Mall to an entrepreneur who wanted to charge admission. This plan was vehemently opposed by those who felt that even in its unkempt condition, the publicly owned National Mall|Mall]] was more worthy of the nation than a commercial public garden with its reputed scenes of debauchery could ever be.[5] This example clearly illustrates the differences between the two senses of the phrase “public garden,” one indicating an improved site open to the citizenry, the other referring to a commercial establishment designed for entertainment.

The type of public garden that provided entertainment in exchange for an admission fee took as its model the successful pleasure gardens of London, sometimes copying the names of the most famous. In the early 19th century, a Vauxhall could be found in nearly every big city in America. Joseph Delacroix wrote of a celebration at the Vauxhall Garden in New York on July 4, 1799:“[The] beautiful garden was opened at 6 o’clock in the morning, and the colours were hoisted under a discharge of 16 guns. The 16 summer houses being the names of the Sixteen United States, each were decorated with the Emblematical Colours belonging to each State, and ornamented with Flowers and Garlands. At 5 o’clock in the evening, the sixteen colours of each Summer-house were carried, at the sound of the musick, to the Grand Temple of Independence, which is 20 feet diameter, and 20 feet high.”[6]

As cities grew larger and more densely populated, citizens sought refuge outside the urban center, seeking “a breathing place to a thickly inhabited city,” as one observer wrote in 1835. In lieu of parks, many colonial estates were transformed into public pleasure gardens, taking advantage of the fine stock of plants that had been cultivated in older private gardens. The 18th-century country seat Lemon Hill in Philadelphia [Fig. 10], for example, was turned into a commercial public garden in the 1830s.

A tension often existed between the marketing of the public gardens as a moral, salubrious “breathing place” and its competing financial goals. The advertising for commercial public gardens promoted them as places of rational amusement, wholesome air, and public taste. In practice, however, the ice cream, slide show, and musical entertainments drew in larger crowds than did the promise of an uplifting, educative environment. Occasionally the term “public garden” was used to refer to a commercial nursery open to the public. That was the case at the McAran Botanic Garden and Nursery in Philadelphia [See Fig. 11], which was operated by the former gardener of The Woodlands and Lemon Hill, two of the most important gardens of the colonial period. His horticultural business also profited from added entertainments, such as a menagerie and the pastries that were offered for sale.

—Therese O'Malley

Texts

Usage

- Anonymous, February 6, 1746, describing a bathgarden in Boston, MA (Boston Weekly New Letter)

- “TO BE LETT, (exclusive of the Bath-House)

- “The Bath-Garden, at the Westerly Part of the Town, which has for many Years been improv’d as a publick Garden, and contains a Variety of the best Fruit-Trees, a great Quantity of Currant and Gooseberry Bushes, some of the best Grape Vines, a handsome Summer-House, Glasses for Hot-Beds, &c. Enquire of John Welch, and know further.”

- Anonymous, January 28, 1771, describing Vauxhall Garden, New York, NY (New York Gazette)

- “To be sold at private Sale, the commodious house and large gardens, in the out ward of this city, known by the name of VAUXHALL; the situation extremely pleasant, having a very extensive view both up and down the North River. . . there are 36 lots and a half of ground laid out to great advantage in a pleasure, and kitchen garden, well stock’d with fruit and other trees, vegetables, &c. and several summer houses which occasionally may be removed; the whole in extreme good order and repair, well fenced in, very fit for a large family, or to entertain the gentry, &c. as a public garden, &c. The premises are on lease from Trinity Church, sixty one years of which are yet to come.”

- Brissot de Warville, J.-P., 1788, describing Philadelphia, PA (1792: 316)[7]

- “Behind the State-house is a public garden; it is the only one that exists in Philadelphia. It is not large; but it is agreeable, and one may breathe in it. It is composed of a number of verdant squares, intersected by alleys.”

- Anonymous, June 21, 1791, Augusta County Order Book (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Sheriff to let the erecting of a pillory and stocks on such part of the public ground as William Bowyer. . . shall direct.”

- Anonymous, July 10, 1805, describing in the New York Commercial Advertiser a public garden in New York, NY (quoted in Garrett 1978: 276)[8]

- “PUBLIC GARDEN. . .

- “MR. PATE, Respectfully informs his friends and the Public in general, that he has taken the GARDEN, formerly Mr. Laight’s near Corlear’s Hook in Walnut-street, two doors from the old Scotch Club House. It will be opened for the reception of company on Sunday, the 15th instant, where they can be accommodated with Ice Cream, Punch, Wine, &c. &c. Ladies and gentlemen may depend upon having their orders executed with the utmost punctuality.”

- Anonymous, 1808, proposal for the creation of a botanic garden, published in the Washington Expositor (quoted in O’Malley 1989: 102)[9]

- “Within the limits of the federal seat there are large and ample reservations for public gardens and other national objects, which may advantageously be applied to the purposes of a botanical garden, a public nursery and an agricultural farm.”

- Foster, Sir Augustus John, c. 1811, describing Washington, DC (1954: 104–5)[10]

- “It was a sad defect for a capital city that there was no public garden whatever in it, tho’ this might so easily have been managed with the palings which surround the presidential house, along the river, or indeed, anywhere within the boundaries at no other cost, in the first instance, than the trouble of cutting through the woods, and, afterwards, of planting. [Note: Since this was written I have been told that there is a garden attached to the President’s House and that the public buildings which have replaced those damaged by the fire was a great improvement.] And what trees there are for a garden indigenous to the spot! The poppinae, gum wood, Bride of China, from ten to twelve varieties of oak, the liquidambar, sassafras, laurus and numerous kinds of magnolia, and tulip trees with lofty stems, fluted in appearance like pillars, and others too many to detail. No city in the world could have a finer pleasure ground, but never was so magnificent a design for a capital so wretchedly and shabbily executed.”

- Anonymous, March 15, 1814, Northampton County Order Book (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Ordered that Caleb B. Upshur be permitted to enclose the public ground west of the courthouse, to sow it in clover and use it as his own until further notice of this court.”

- Lane, Samuel, 1820, describing George Bridport’s proposal for Washington Square, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in O’Gorman et al. 1986: 68)[11]

- “[I am writing] to ascertain the artist who designed the public Garden on Chestnut Street [sic] at the place (if I am not mistaken) formerly called Potters field; and if he is in your town inquire if he would come on here [Washington, DC] to furnish a design for Improving the Capitol Square.” [Fig. 12]

- Hunt, Henry, William Elliot, and William Thornton, 1826, committee requesting a Memorial to the House of Representatives of the Congress in Washington, DC (U.S. Congress, 19th Congress, 1st Session, House of Representatives, doc. 123, book 138)

- “That, with a view to promote the public good, and to ornament and improve the public grounds, they would recommend that the water of Tiber Creek be brought to the Capitol Square; and, after forming a reservoir, be carried in pipes to the Botanic Garden, and thrown up in a jet d’eau of 30 or 40 feet high, and then be used in watering the surrounding grounds. That a wall five feet high, with a stone coping, be put round the ground appropriated for a Botanic Garden; and that suitable buildings be erected, and the Garden be properly laid out, and cultivated as a National Garden; to effect which important national objects, a sum not exceeding 30,000 dollars will be required.”

- Bulfinch, Charles, January 21, 1829, proposal to the House Committee on Public Buildings regarding the national Mall, Washington, DC (quoted in Rathburn 1917: 49)[12]

- “The Capitol being now finished with the exception of these particular objects, I beg leave to suggest that the public grounds immediately adjacent should conform in some degree to the importance and high finish of the building.”

- Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1830, describing the McAran Botanic Garden and Nursery, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Boyd 1929: 433)[13]

- “It contains 6 acres, and is the largest public garden about the city. Here may be seen part of the celebrated collection of plants that formerly belonged to William Hamilton, of the Woodlands, and now the property of Mr. D’Arras [McAran].” [Fig. 11]

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), March 1835, “Notices of some of the Gardens and Nurseries in the neighborhood of New York and Philadelphia” (American Gardeners’ Magazine 1: 241)[14]

- “There is another class of gardens in Philadelphia, called public gardens, which combine in addition to a flower garden, green-houses, hothouses, &c., a bar-room or tavern; this latter addition we are far from believing useful or needful. Gardens for public amusement and recreation are very desirable in large cities, and we should be happy if our own contained one, layed out with taste, and with some knowledge of Landscape scenery, and properly and judiciously conducted. There is something of the kind much needed; and now that even the few fine private gardens which have heretofore attracted the admiration of the stranger as well as the citizen, and which have beautified the appearance of the city, seeming like rich and fertile fields, in the midst of barren wastes—now, that these (one of which, we had hoped, would have ever remained, if not in private hands, as a public garden, and as a breathing place to a thickly inhabited city) are cut up and destroyed in the tide of public improvements—to make room for piles of brick and stone—the want of them will be more quickly perceived. There is scarcely a city in England, or upon the continent, but has its public gardens, ‘Tea gardens,’ or something of the kind.”

- Russell, John Lewis, 1837–38, describing Boston, MA (1839: 34–35)[15]

- “Efforts have been making, during the past summer to establish a public Garden in the city of Boston, to consist of a choice collection of greenhouse and out-door plants, shrubs, trees, &c. The plan may be considered good, and may promise after a few years, valuable to the cause of horticulture, and towards creating a taste for one of the most refined sources of recreation in society.”

- Alcott, William A., 1838, “Embellishment and Improvement of Towns and Villages” (American Annals of Education 8: 341–42)[16]

- “We wish to see not only spacious squares or commons interspersed with shade, if not with fruit trees, in every village and town and city, but we wish to see public gardens on an extensive scale. We wish to see these not only for health’s sake, and for the sake of their moral tone and tendency, but as a means of rational amusement—as a means of promoting the public cheerfulness, the public taste, and of consequence, the public happiness.”

- Adams, Nehemiah, 1838, The Boston Common (1838: 45–46)[17]

- “It is gratifying to learn that measures have been taken for the laying out of a public garden on the lands below the Common. . .

- “It ought, in a word, to be a permanent repository of whatever is rare, beautiful, new and useful, in the vegetable creation, as well as in the other kingdoms of nature.” [See Fig. 8]

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1841, describing New York, NY (1841: 1:38–39)[18]

- “Of the public places for air and exercise with which the Continental cities of Europe are so abundantly and agreeably furnished, and which London, Bath, and some other of the larger cities of England contain, there is a marked deficiency in New-York. Except the Battery, which is agreeable only in summer—the Bowling Green is a confined space of 200 feet long by 150 broad; the Park, which is a comparatively small spot of land (about ten acres only) in the heart of the city, and quite a public thoroughfare; Hudson Square, the prettiest of the whole, but small, being only about four acres; and the open space within Washington Square, about nine acres, which is not yet furnished with gravel-walks or shady trees—there is no large place in the nature of a park, or public garden, or public walk, where persons of all classes may take air and exercise. This is a defect which, it is hoped, will ere long be remedied, as there is no country, perhaps, in which it would be more advantageous to the health and pleasure of the community than this to encourage, by every possible means, the use of air and exercise to a much greater extent than either is at present enjoyed.”

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1841, describing Baltimore, MD (1841: 1:281)[18]

- “There are some public gardens in Baltimore, the Columbian, Vauxhall, and the Citizen’s Retreat; and public baths have been lately introduced on a good scale.”

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1841, describing U.S. Capitol, Washington, DC (1841: 1:198–99)[18]

- “The other front [of the Capitol] is to the west, and overlooks the western portion of the city below it, the slope of the western declivity being ornamented with terraces, walks, and shrubbery. The area of the public grounds thus laid out, and in the centre of which, or nearly so, the Capitol stands, is about thirty acres; the whole of this is enclosed by a low wall of stone, with good iron railings, and entered by well-built gateways, opposite to the different avenues leading to and from it as a general centre.”

- Adams, Nehemiah, 1842, describing Boston Common, Boston, MA (1842: 51)[19]

- “The mention of public exhibitions on the Common brings to mind. . . a source of serious apprehension. The centre of the Common is obstructed by rows of young but thrifty and fast increasing trees. They were planted along the principal paths, for the benevolent purpose of affording shade to those who cross the Common. Their usefulness even in this respect is doubtful, and there is more than a doubt respecting their good influence upon the Common as a public ground. Our summers are so short, the air of the Common is generally so cool or in such good circulation, that the use of shaded walks through its centre is very small compared with the desirableness of having one large open place, as the Common has always been, in a crowded city. We do not need the whole Common as a mere parasol; its wide and free grounds and prospect are its chief beauty, and the shaded malls are sufficient as places of resort from the heat. . . There will soon be an end to great public exhibitions on the Common, if the trees now in the centre should thrive.”

- Dickens, Charles, 1842, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (1842: 122)[20]

- “Philadelphia is most bountifully provided with fresh water, which is showered and jerked about, and turned on, and poured off, everywhere. The Waterworks, which are on a height near the city, are no less ornamental than useful, being tastefully laid out as a public garden, and kept in the best and neatest order.” [Fig. 13]

- Mathews, Cornelius, 1842, describing Vauxhall Garden, New York, NY (quoted in Garrett 1978: 391)[8]

- “Puffer entering, was overwhelmed with the gorgeousness and splendor of the spectacle that broke upon him. In the first place, the Garden, to which he was a stranger, was filled with trees— which was a novelty in a New-York public garden—some short and bushy, others tall and trim, but actual trees; then there were a thousand eyes or better lurking and glaring out in every direction, in the shape of blue and yellow and red and white lamps, fixed among the trees and against the stalls; then there was a fountain; and then, through two rows of poplars, commanding a noble prospective of two white chimney-tops in the rear, there stretched a floor—the ball-room floor itself.”

- Mudd, Ignatius, 1849, describing the grounds of the United States Capitol and the reconstruction of the national Mall, Washington, DC (U.S. Congress, 31st Congress, 1st Session, doc. 30)

- “A disposition on the part of Congress to make the public grounds what they were originally designed to be. . . An ornament and attraction to the capital of the nation.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1851, describing plans for improving the public grounds of Washington, DC (quoted in Washburn 1967: 54)[21]

- “The Public Grounds now to be improved I have arranged so as to form six different and distinct scenes.”

- Sylvanus [pseud.], May 1851, describing a public garden outside New Orleans, LA (Horticulturist 6: 221–22)[22]

- “There is a public garden about six miles from the city. It is a common resort, particularly on Sundays, when as it is easily accessible by railroad, thousands flock to it to get a little fresh air and a nosegay. It is laid out in the English style, and is a pleasant place of retreat from the heat and stench of this dirtiest of all cities. It, however, possesses no horticultural or botanical attraction. The garden is a source of profit from its flowers, but I suspect more money is made from the sale of liquor in the hotel which is connected with it. It is owned by the railroad company, and is the only attraction at that terminus of the line.”

Citations

- Waterhouse, Benjamin, 1811, The Botanist (quoted in O’Malley 1989: 94)[9]

- “By public gardens, medicinal plants are at the command of the teacher in every lesson, the eye and the mind are perpetually gratified with the succession of curious, scarce and exotic luxuries, here the botanists can compare the doubtful species, and examine them through all the stages of growth, with those to which they are allied, and all these advantages are accumulated in a thousand objects at the same time.”

- Gordon, Alexander, June 1832, “Notices of some of the principle Nurseries and private Gardens in the United States of America,” describing the establishment of James Bloodgood and Co., vicinity of Flushing, NY (Gardener’s Magazine 8: 277–78)[23]

- “Gardening, in the United States of America, can never arrive at that degree of perfection which it has done in England: the nature of the American government makes this utterly impossible. The abolition of entails, and the repeal of the law of primogeniture, naturally break down into small portions the estates of even the greatest landholders. . . Still, this may be remedied, by uniting, and forming public gardens; the only method by which gardening can arrive at perfection in the United States.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1834, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1834: 1206)[24]

- “6861. Public gardens are designed for recreation, instruction, or commercial purposes. The first include equestrian and pedestrian promenades; the second, botanic and experimental gardens; the third, public nurseries, market-gardens, florists’ gardens, orchards, seed-gardens, and herb-gardens.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), 1844, “Notes and Recollections of a Tour, through part of England, Scotland and France,” describing the Derby Arboretum (Magazine of Horticulture 11: 122)[25]

- “Few of our cities or large towns, have done any thing towards establishing places for the health and recreation of the inhabitants. Boston with its beautiful Common, and Philadelphia with its elegant squares, stand before other cities; but in the newer towns which have recently sprung up, there have been scarcely any which have made any provision for gardens or grounds, where the public could resort and breathe fresh air. We know of no one object so well deserving the attention of men of wealth, who wish to do a noble service to the public, than the formation of public gardens free to all, in crowded towns or cities.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, October 1848, “A Talk About Public Parks and Gardens” (Horticulturist 3: 154, 156)[26]

- “I am thinking of PUBLIC PARKS and GARDENS—those salubrious and wholesome breathing places, provided in the midst of, or upon the suburbs of so many towns on the continent—full of really grand and beautiful trees, fresh grass, fountains, and, in many cases, rare plants, shrubs and flowers. . .

- “Make the public parks or pleasure grounds attractive by their lawns, fine trees, shady walks and beautiful shrubs and flowers, by fine music, and the certainty of ‘meeting everybody,’ and you draw the whole moving population of the town there daily. . .

- “you must remember that there is no forced intercourse in the daily reunions in a public garden or park. There is room and space enough for pleasant little groups or circles of all tastes and sizes, and no one is necessarily brought into contact with uncongenial spirits; while the daily meeting of families, who ought to sympathise, from natural congeniality, will be more likely to bring them together than any other social gatherings. Then the advantage to our fair countrywomen—health and spirits, of exercise in the pure open air, amid the groups of fresh foliage and flowers, with a chat with friends, and pleasures shared with them, as compared with a listless lounge upon a sofa at home, over the last new novel or pattern of embroidery!”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, January 1849, “Domestic Notices: Public Parks and Gardens” (Horticulturist 3: 348)[27]

- “Upon my life, I believe handsome public grounds, with music, would have the happiest influence in allaying riots and debauchery, crime and secret vices. The workman must have recreation. The rich had better give it than to pay for prisons and penitentiaries.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, July 1849, “Public Cemeteries and Public Gardens” (Horticulturist 4: 9–11)[28]

- “. . . in the absence of great public gardens, such as we must surely one day have in America, our rural cemeteries are doing a great deal to enlarge and educate the popular taste in rural embellishment. They are for the most part laid out with admirable taste; they contain the greatest variety of trees and shrubs to be found in the country, and several of them are kept in a manner seldom equalled in private places. . .

- “But does not this general interest, manifested in these cemeteries, prove that public gardens, established in a liberal and suitable manner, near our large cities, would be equally successful? . . . Would not such gardens educate the public taste more rapidly than anything else? And would not the progress of horticulture, as a science and an art, be equally benefitted by such establishments? The passion for rural pleasures is destined to be the predominant passion of all the more thoughtful and educated portion of our people; and any means of gratifying their love for ornamental or useful gardening, will be eagerly seized by hundreds of thousands of our countrymen.”

Images

Inscribed

Jeromes, Gilbert, Grant and Company, Shelf Clock, 1839–40. “Public Square New Haven.”

A. J. Downing, Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington, 1851.

A. J. Downing, Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington, 1851. Manuscript copy by Nathaniel Michler, 1867.

Associated

Christian Remick, A Prospective View of part of the Commons, c. 1768.

Thomas Jefferson, Plan for the City of Washington, March 1791.

John T. Bowen, A View of the Fairmount Water-Works with Schuylkill in the distance, taken from the Mount, 1838.

M. Schmitz (artist), Thomas S. Sinclair (lithographer), John B. Colahan (surveyor), Map of Washington Square, Philadelphia, 1843.

Attributed

George Bridport, Alternative designs for Washington Monument, Washington Square, Philadelphia, 1816.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Castle Garden, N. York, c. 1825–28.

Hugh Bridport, The Pagoda and Labyrinth Garden, c. 1828.

FitzHugh Lane after Charles Hubbard, The National Lancers with the Reviewing Officers on Boston Common, 1837.

William Wade, Castle Garden: From the Battery, 1848. This view shows two public gardens. The Battery, an open, free promenade, and Castle Gardens, a commercial garden with bathing facilities.

Notes

- ↑ For the vernacular tradition of public parks and gardens see the following: John Brinckerhoff Jackson, “The Origin of Parks,” in Discovering the Vernacular Landscape (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1984), 125–30, view on Zotero; John Brinckerhoff Jackson, “The Public Landscape,” in Landscapes: Selected Writings of J. B. Jackson (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1970), 153–60, view on Zotero; and Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, The Park and the People: A History of Central Park (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992), 59–91, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward M. Riley, “The Independence Hall Group,” in Historic Philadelphia: Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 43, part 1 (1953): 7–8, view on Zotero. See also Elizabeth Milroy, “‘For the like Uses, as the Moore-fields’: The Politics of Penn’s Squares,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 130, no. 3 (July 2006): 258–82, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph S. Wood, The New England Village (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 128–29, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Rudy J. Favretti, “The Ornamentation of New England Towns: 1650–1850,” Journal of Garden History 2 (October 1982): 325–42, view on Zotero. See also Neil Harris, The Artist in American Society: The Formative Years 1790–1860 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1970), 209, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Rathburn, “The Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences,” United States National Museum’s Bulletin 101 (1917): 45–46, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Harold Donaldson Eberlein and Cortlandt Van Dyke Hubbard, “The American ‘Vauxhall’ of the Federal Era,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 68 (April 1944): 150–74, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J.-P. (Jacques-Pierre) Brissot de Warville, New Travels in the United States of America, Performed in 1788, ed. Durand Echeverria, trans. Maro S. Vamos and Durand Echeverria (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 1964), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Thomas Myers Garrett, “A History of Pleasure Gardens in New York City, 1700–1865” (PhD diss., New York University, 1978), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Therese O’Malley, “Art and Science in American Landscape Architecture: The National Mall, Washington, DC, 1791–1852” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1989), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sir Augustus John Foster, Jeffersonian America: Notes on the United States of America Collected in the Years 1805–1806–1807 and 1811–1812, ed. Richard Beale Davis (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1954), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James F. O’Gorman et al., Drawing Toward Building: Philadelphia Architectural Graphics, 1732–1986 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press for the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1986), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Rathburn 1917, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Boyd, A History of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1827–1927 (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1929), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notices of Some of the Gardens and Nurseries in the Neighbourhood of New York and Philadelphia; Taken from Memoranda Made in the Month of March Last,” American Gardener’s Magazine, and Register of Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Horticulture and Rural Affairs 1, no. 7 (July 1835): 241–46, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Lewis Russell, Report of the Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society for the Year 1837–8 (Boston: Tuttle, Dennett & Chisholm, 1839), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William A. Alcott, “Embellishment and Improvement of Towns and Villages,” American Annals of Education 8, no. 8 (August 1838): 337–47, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Adams, The Boston Common, or Rural Walks in Cities (Boston: George W. Light, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 James Silk Buckingham, America, Historical, Statistic, and Descriptive, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Adams, Boston Common (Boston: William D. Ticknor and H. B. Williams, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Dickens, American Notes (Paris: Baudry’s European Library, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Wilcomb E. Washburn, “Vision of Life for the Mall,” AIA Journal 47 (1967): 52–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sylvanus [pseud.], “Random Notes on Southern Horticulture,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 6, no. 5 (May 1851): 220–24, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Gordon, “Notices of Some of the Principal Nurseries and Private Gardens in the United States of America, Made during a Tour through the Country, in the Summer of 1831; with Some Hints on Emigration,” Gardener’s Magazine and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 8, no. 38 (June 1832): 277–89, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed. (London: Longman et al., 1834), view on Zotero.

- ↑ C. M. Hovey, “Notes and Recollections of a Tour, through part of England, Scotland and France, in the autumn of 1844,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 11, no. 4 (April 1845): 121–34, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, “A Talk About Public Parks and Gardens,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 4 (October 1848): 153–58, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, “Domestic Notices: Kiosques or Summer Houses,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 7, no. 1 (January 1852): 339, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, “Public Cemeteries and Public Gardens,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 4, no. 1 (July 1849): 9–12, view on Zotero.