Difference between revisions of "Icehouse"

m |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 187: | Line 187: | ||

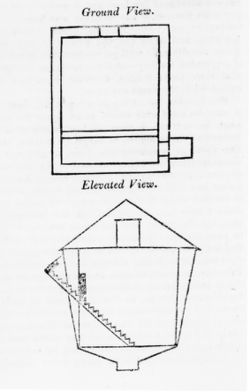

:“Fig. 64 is a [[square]] '''ice-house''', with a roof projecting three or four feet, and covered with shingles, the lower ends of which are cut so as to form diamond pattern when laid on the roof. The [[Rustic_style|rustic]] brackets which support this roof, and the [[Rustic_style|rustic]] [[column]]s of the other design, will be rendered more durable by stripping the bark off, and thoroughly painting them some neutral or wood tint.*[Fig. 7] | :“Fig. 64 is a [[square]] '''ice-house''', with a roof projecting three or four feet, and covered with shingles, the lower ends of which are cut so as to form diamond pattern when laid on the roof. The [[Rustic_style|rustic]] brackets which support this roof, and the [[Rustic_style|rustic]] [[column]]s of the other design, will be rendered more durable by stripping the bark off, and thoroughly painting them some neutral or wood tint.*[Fig. 7] | ||

:“*The projecting roof will assist in keeping the building cool. In filling the house, back up the wagon loaded with ice, and slide the squares of ice to their places on a plank serving as an inclined plane.” | :“*The projecting roof will assist in keeping the building cool. In filling the house, back up the wagon loaded with ice, and slide the squares of ice to their places on a plank serving as an inclined plane.” | ||

| − | [[File:0781.jpg|thumb|Fig. 8, Frances Palmer, Plan and section of Villa at Oswego, New York, in [[William H. Ranlett]], ''The Architect'' (1851), vol. 2, pl. 12.]] | + | [[File:0781.jpg|thumb|Fig. 8, [[Frances Palmer]], Plan and section of Villa at Oswego, New York, in [[William H. Ranlett]], ''The Architect'' (1851), vol. 2, pl. 12.]] |

| Line 227: | Line 227: | ||

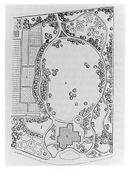

File:0378.jpg|Anonymous, “Plan of a Suburban Villa Residence,” in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'', 4th ed. (1849), 118, fig. 26. | File:0378.jpg|Anonymous, “Plan of a Suburban Villa Residence,” in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'', 4th ed. (1849), 118, fig. 26. | ||

| − | File:0781.jpg|Frances Palmer, Plan and section of Villa at Oswego, New York, in [[William H. Ranlett]], ''The Architect'', 2 vols. (1851), vol. 2, pl. 12. | + | File:0781.jpg|[[Frances Palmer]], Plan and section of Villa at Oswego, New York, in [[William H. Ranlett]], ''The Architect'', 2 vols. (1851), vol. 2, pl. 12. |

| − | File:0787.jpg|Frances Palmer, “Ground Plot,” in [[William H. Ranlett]], ''The Architect'', 2 vols. (1851), vol. 2, pl. 29. | + | File:0787.jpg|[[Frances Palmer]], “Ground Plot,” in [[William H. Ranlett]], ''The Architect'', 2 vols. (1851), vol. 2, pl. 29. |

File:1097.jpg|Thomas S. Sinclair, “Plan of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane at Philadelphia,” in Thomas S. Kirkbride, ''American Journal of Insanity'' 4, no. 4 (April 1848): plate opp. 280. | File:1097.jpg|Thomas S. Sinclair, “Plan of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane at Philadelphia,” in Thomas S. Kirkbride, ''American Journal of Insanity'' 4, no. 4 (April 1848): plate opp. 280. | ||

Revision as of 20:06, December 3, 2019

(Ice house, Ice-house)

See also: Temple

History

The term icehouse, or ice house, as dictionary definitions make clear, refers to a structure for preserving ice year round and for keeping food and beverages cool during the warm months. Icehouses ranged in scale from small outbuildings for domestic use to larger warehouse-sized buildings designed for the commercial ice-harvesting industry.[1] In the context of American landscape design, domestic icehouses were often incorporated into the overall plan of an estate. While functional requirements dictated below-ground construction, the visible parts of the structure were often designed to enhance ornamental aspects of the grounds.

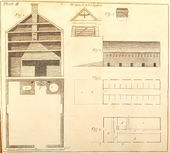

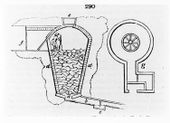

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the construction of icehouses generally followed the European tradition. An underground pit was excavated, in the shape of an inverted cone, and then covered by a mound or a structure whose exterior walls took a variety of shapes. The angled walls of the pit, such as those depicted in a profile drawing published in William Ranlett’s The Architect (1851), helped to keep the ice densely packed as it was loaded into the pit and subsequently to keep the ice a solid mass, even as it melted. Because, as Robert Morris (1784) noted, “the closer it is packed the bet[ter i]t keeps,” it was important to design icehouses with openings large enough to pack the ice solidly. Commercial icehouses needed to deliver closely packed blocks of ice throughout the warm seasons, but residential icehouses more often preserved ice to cool the air for food preservation and occasional ice chipping. In this domestic context, the strategy was to try to pack as solid a mass as possible by breaking the ice into pieces and ramming it into place. Since dampness was the greatest impediment to the preservation of ice, drains or other means of conducting runoff usually were built into the base of these structures. In addition, straw mats or sawdust were added to insulate the ice from sun and drafts, as described by George Washington and J. S. Williams (1823) and illustrated by J. B. Bordley in his Essays and Notes on Husbandry and Rural Affairs (1801).[2]

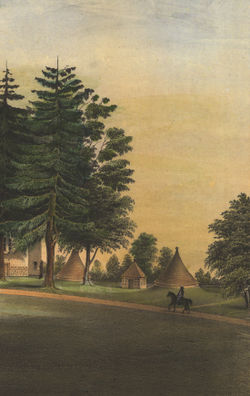

The structure covering the pit took a variety of forms and materials. The feature ranged from a simple earthen mound, seen in Samuel McIntire’s sketches of the ice cellar at Pleasant Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts [Fig. 1], to the more elaborate ornamental styles that harmonized with larger landscape design. For instance, at Montpelier, Thomas Jefferson designed a neoclassical temple to cover the subterranean icehouse, a style that echoed the architecture of the nearby main house [Fig. 2]. During the 19th century, icehouses were designed in a variety of architectural styles to complement landscape design, as illustrated in designs for ornamental icehouses published in the Horticulturist in 1846 [Fig. 3]. Most icehouses also contained antechambers, vaults, or superstructures where food, such as meat and dairy products, were stored. J. S. Williams, in an 1823 letter to the editor of the New England Farmer, detailed the construction and advantages of an “ice closet” attached to his icehouse. This separate area used the air cooled by the ice to preserve food and was recommended for those who did not have a spring house (which provided a common way to keep food cool) or those who wanted to avoid the musty flavor of meat laid directly on the ice. In other cases, such as J. B. Bordley’s section of an icehouse published in an appendix to Richard Parkinson’s A Tour in America (1805) [Fig. 4], the structure consisted only of an ice pit with no storage area.

In the 18th century a private icehouse was something of a luxury for a homeowner, as suggested by the relative scarcity of examples in sources other than treatises. Prior to 1800, most families preserved their food by drying, smoking, and salting, or by storing it in cold cellars, spring houses, and dairies. Private icehouses were constructed principally by wealthy plantation or estate owners. Other icehouses were built by proprietors of taverns, public gardens, and other eating and drinking establishments, such as Joseph Delacroix’s Ice-House Garden (later Vauxhall Garden) in New York. These icehouses, in addition to preserving food, made it possible to serve iced drinks, desserts, and ice cream. Several advertisements of tavern sales prominently listed an icehouse with other assets. In at least one instance, in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1820, a vendor of ice cream, punch, and lemonade referred to his entire establishment as an “icehouse.” In 1811 Rev. William Bentley commented upon the growth in the Salem, Massachusetts, area of such pleasure establishments, many of which he noted had icehouses. He wrote, “The places of amusement are so much multiplied that the season is not long enough to give them all one visit. The principal places are at Orne’s point at the Villa, at the Hotels . . . at Spring Pond . . . at Nahant & Philip’s beach, besides as many little places for humble folk to crawl in all directions.”[3]

It was not until the first half of the 19th century that icehouses became common for residences, and then mainly for rural sites beyond the reach of commercial suppliers. Beginning in the early 19th century, proponents, such as Frederic Tudor (1806), began to argue the merits of above-ground icehouses with no underground pits; they were cheaper to build, easier to load, unload, and ventilate, and they were equally effective in preserving ice. Above-ground icehouses became the standard for larger-scale icehouses associated with communities, such as those of the Shakers, and also with the growing commercial industry. This increase in the availability of commercially produced ice, at least in heavily settled areas, is exemplified by comments in the New England Farmer (1835) about increasing ice consumption. The increase in icehouse construction was also due to changes in the 1830s and 1840s in the American diet, which included more fresh meats and vegetables.[4]

Icehouses were sited in relation to a combination of factors, including accessibility to the kitchen, proximity to an ice source, a location on an elevated and potentially well-drained place, and aesthetics. Thomas Moore, in an 1803 essay about icehouse construction, suggested placing one’s icehouse on the north face of a hill, preferably sheltered from prevailing winds. At Gen. Charles Ridgely’s estate, Hampton, in Baltimore, and Montpelier, the icehouse was placed on the north side of a gentle incline, near the front door of the main house. In each case the potential visual intrusion of the icehouse was minimized. At Hampton, it was covered by an earthen mound; at Montpelier, it was surmounted by a domed temple. In other cases the icehouse was incorporated more subtly into the landscape design [Fig. 5]. The icehouse pictured in the Horticulturist was sited in a densely planted area and dressed in a rustic picturesque so that it blended into the naturalistic landscape.

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Marshman, William, February 16, 1769, describing an expense at the Governor’s Palace, Williamsburg, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “To 1 Man 5 days filling the Ice House at 1s 3d.”

- Morris, Robert, June 15, 1784, in a letter to George Washington, describing The Hills (later Lemon Hill), estate of Robert Morris, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Riley 1989: 8)[5]

- “My Ice House is about 18 feet deep and 16 square, the bottom is a Coarse Gravell & the water which drains from the ice soaks into it as fast as the Ice melts, this prevents the necessity of a Drain which if the bottom was Clay or Stiff Loam would be necessary and for this reason the side of a hill is preferred generally for digging an Ice House, as if needful a drain can easily be cut from the bottom of it, through the side of the Hill to let the Water run out. The Walls of my Ice House are built of stone without Mortar (which is called Dry Wall) untill within a foot and a half of the Surface of the Earth when Mortar was used from thence to the Surface to make the top more binding and Solid. When this Wall was brought up even with the Surface of the Earth I stopped there and then dug the foundation for another Wall, two foot back from the first and about two foot deep, this done the foundation was laid so as to enclose the whole of the Walls built on the inside of the Hole where the Ice is put and on this foundation is built the Walls which appear above ground and in mine they are about ten foot high. On these the Roof is fixed, these walls are very thick, built of Stone and Mortar, afterwards rough Cast on the outside. I nailed a Cieling of Boards under the Roof flat from Wall to Wall, and filled all the Space between that Cieling and the Shingling of the Roof with Straw so that the heat of the Sun Cannot possibly have any Effect.

- “In the Bottom of the Ice House I placed some Blocks of Wood about two foot long and on these I laid a Plat form of Common Fence Rails Close enough to hold the Ice open enough to let the Water pass through, thus the Ice lays two foot from the Gravel and of Course gives room for the Water to soak away gradually without being in contact with the Ice, which if it was for any time would waste it amazingly. . . .

- “I find it best to fill with Ice which as it is put in should be broke into small pieces and pounded down with heavy Clubs or Battons such as Pavers use, if well beat it will after a while consolidate into one solid mass and require to be cut out with a Chizell or Axe. I tryed Snow one year and lost it in June. The Ice keeps until October or November and I believe if the Hole was larger so as [to h]old more it would keep untill Christmass, the closer it is packed the bet[ter i]t keeps and I believe if the Walls were lined with Straw between the Ice [and] Stone it would preserve it much, the melting begins next the Walls and Continues round the Edge of the Body of Ice throughout the Season.”

- Washington, George, 1785, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (Jackson and Twohig, eds., 1978: 4:213, 221)[6]

- “[October 26] Took the cover off my dry Well, to see if I could not fix it better for the purpose of an Ice House, by Arching the Top, and planking the sides. . . .

- “[November 9] Having put in the heavy frame into my Ice House I began this day to Seal it with Boards, and to ram straw between these boards and the wall. All imaginable pains was taken to prevent the Straw from getting wet, or even damp, but the moisture in the air is very unfavourable.”

- Constantia [Judith Sargent Murray], June 24, 1790, “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania” (Massachusetts Magazine 3: 414)[7]

- “Underneath this summer house, is an ice house, convenient and well planned, and upon the right of this building is an oblong section of the garden, prettily enclosed, which is chiefly devoted to exotics.”

- Washington, George, October 14, 1792, in a letter to Anthony Whiting, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (quoted in Martin 1991: 216)[8]

- “The flowering ever-green Ivy, I want them to plant thick around the Ice house upper side, not of the tallest kind, but of an even height. . . . The like at the No. East of the same lawn, by the other Wall [and if] the Path leading from the Bars to the Wild Cherry tree in the Hollow, was pretty thickly strewed with them (of the lower sort) and intermixed freely with the bush honey suckle of the Woods, it would, in my opinion, have a pleasing effect.”

- Anonymous, August 27, 1795, describing in the Alexandria Gazette a tavern property in Annapolis, MD (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Indian Queen. FOR SALE, THAT well known Tavern and Stage House . . . containing thirty-three well furnished convenient rooms, with arched and other excellent cellars underneath the whole; also, an ice-house built on the best construction, which will contain fifty large loads.”

- Brooks, Joshua, 1799, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (quoted in Riley 1989: 18)[5]

- “At the back of the house is a covered staircase to the kitchen or cellar. Here many male and female negroes were at work digging and carrying away the ground to make a level grass plot with a gravel walk around it, at one end of which is an ice house.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1799, describing a lunatic asylum in New York, NY (1822: 3:454)[9]

- “Among its conveniences are an excellent garden, fruit trees, walks, a large ice-house, bathing-house, and stables.”

- Anonymous, March 2, 1802, describing a property for sale in King George County, VA (Virginia Herald)

- “It lies on the Rappahannock river, about three miles from the town of Port Royal, and twenty four from Fredericksburg. . . .

- “I have lately erected a two story dwelling House, and some necessary out houses . . . an eighteen feet cube Ice house, and a thriving young bearing Peach Orchard, of 1000 trees.”

- Anonymous, March 27, 1803, describing in the Virginia Herald a property for sale in Westmoreland, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “FOR SALE, the Tract of Land, whereon I reside . . . and a new and well constructed Ice House, stand on an eminence, commanding a beautiful and extensive view of the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers.”

- Anonymous, December 12, 1805, describing in the Enquirer the hours of operation and scheduled events at Hay Market Garden in Richmond, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “HAY MARKET GARDEN. THE proprietor of the Hay Market Garden, respectfully notifies the citizens of Richmond, Manchester, and the public generally, that the garden will be kept open during the session of the General Assembly. . . . An excellent ice house may be annexed to the garden.”

- Foster, Sir Augustus John, 1812, describing the White House, Washington, DC (1954: 12)[10]

- “He [James Hoban, architect of the White House] left out the upper story however and built no cellars, which President Jefferson, after experiencing great losses in wines, has been obliged to add at a depth of sixteen feet under ground. These are so cool that the thermometer stood two degrees lower in them than it did in a vacant spot in the ice-house early in July, when in the shade out of doors it was at ninety-six.”

- Anonymous, 1814, describing in the Raleigh Star a resort at Shocco Springs, Warren County, NC (quoted in Lounsbury, ed.,1994: 187)[11]

- “. . . additions and improvements have been made to his buildings, so as to render them more commodious and comfortable than heretofore. His Ice House is well stored with ice.”

- Anonymous, September 14, 1816, describing a property for sale in Spotsylvania County, VA (Virginia Herald)

- “NOTICE. The subscriber being desirous to remove to the Western Country, will sell the well known TAVERN & FARM. . . .

- “The tavern is 44 feet by 40, two stories high, conveniently laid off into rooms . . . all well finished, good kitchen, stables for 100 Horses, Ice-house.”

- Anonymous, December 23, 1816, describing in the Cumberland County Deed Book articles of lease agreement in Cumberland County, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “For the year 1817, Thomas Hobson and Richard S. Eggleston are to have the use of the ice house in partnership, and if upon trial, one will suffice both, they will continue to use it as aforesaid during the continuance of the lease.”

- Anonymous, July 29, 1818, describing in the Virginia Herald a property for sale in Spotsylvania County, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Valuable property for sale. Will be offered at public auction, on the first Monday of August next, on the premises, that well known tavern and tract of land, at Spotsylvania court-house . . . there is an ice house and all other houses necessary. . . . The improvements are . . . all necessary out houses, including an ice house.”

- Forman, Martha Ogle, April 16, 1819, describing Rose Hill, home of Martha Ogle Forman, Baltimore County, MD (1976: 80)[12]

- “Moved Ramsey’s bed to the Sky parlor over the Ice house.”

- Anonymous, 1820, describing in the Raleigh Register the opening of an ice-house in Raleigh, NC (quoted in Lounsbury, ed., 1994: 188)[11]

- “DAVID SHAW has opened his Ice-House, and is prepared to furnish Ice-Cream, Punch or Lemonade, every day (the Sabbath excepted) from 10 in the morning til 10 at night. He will also sell Ice by the pound.”

- Anonymous, September 30, 1820, describing in the Virginia Herald a property for sale in Culpeper County, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “I will sell my tavern establishment . . . consisting of . . . A large and commodious house with four rooms below stairs and eight above, with two large porticoes—a new smoke house, a new ice house.”

- Williams, J. S., October 2, 1823, “Ice Houses—With Ice Closets Attached” (New England Farmer 2: 125)[13]

- “I herewith hand yon [sic] a sketch of my ice closet attached to my ice house. . . . The citizen and farmer may both enjoy its comforts—the latter more particularly, will soon know its value, where he is deprived of the benefits of a good spring. The greatest importance, however, attached to its use, I conceive to be the preservation of fresh meats, which I have kept for three weeks, as sound and wholesome, as the day it was placed in the closet, being entirely free from the musty and clammy flavour which it is apt to partake of, when confined in the customary way on the top of the ice. The only danger I apprehended, was the fear of losing my ice sooner in the season, from the closet drawing its quantum of cold atmosphere from the ice: I am happy to find, however, that my house still contains a body of ice, although it was little more than half filled, and (from my absence,) very imperfectly rammed. The size of my house is twelve feet square, and in depth to the floor, there being a space of one foot underneath, sloped to the centre where there is a well of two feet, to receive any water which may pass from the ice. The closet is four feet in width, which affords sufficient room for a private family. . . . The pit is dug about three feet wider at top than bottom, the house being built perpendicular, (of logs or plank, mine is the former.) will leave a cavity eighteen inches wide at top, round the house, in which straw is to be closely crammed; this, with a layer of straw at bottom and straw mats laid over the top of the ice; will be quite sufficient for its preservation.” [Fig. 6]

- Silliman, Martha Trumbull, September 1, 1821, describing Monte Video, property of Daniel Wadsworth, Avon, CT (quoted in Saunders and Raye 1981: 20)[14]

- “The place is a great deal handsomer than I expected. The buildings are all Gothic. First there is Uncles beautiful house; 2d the tower, 3d the cottage & the barns 4th the boat house & 5th the bathing house 6th a grape house 7th an ice house & 8th the bee house & a Gothic gate.”

- Q., December 22, 1826, “On Ice-Houses” (New England Farmer 5: 173)[15]

- “Having had some experience in preserving ice, in the latitude of Maryland, I will place at your disposal a few observations, as an addition to the generally judicious directions of P. The shade of trees over the house, but not so much as to obstruct a good circulation of air, is a point of importance.”

- Trollope, Frances Milton, 1828, describing Cincinnati, OH (1832: 1:132)[16]

- “We found ourselves much more comfortable here [in the country] than in the city. The house was pretty and commodious, our sitting-rooms were cool and airy; we had got rid of the detestable mosquitoes, and we had an ice-house that never failed.”

- Anonymous, May 20, 1835, “Ice and Ice-Houses” (New England Farmer 13: 353)[17]

- “We intend, however, to say a few words of ice and ice houses, that may interest the reader. There are persons younger than ourself who can remember when the only ice sold in Boston, was brought to the city in parcels of ten or fifteen pounds in the box of a market gardener’s cart, and sold as a very great luxury at a corresponding price. There were then no ice-houses in the vicinity, except a few gentlemen’s country seats, and they were built under ground, and were of small capacity. Within the last twenty years the consumption has become so general, and the cost is so small, that ice is no longer deemed a luxury, but one of the necessaries of life.”

Citations

- Bradley, Richard, 1720, New Improvements of Planting and Gardening (1720: 2.3:257)[18]

- “. . . unless they were to be kept in Ice-Houses during the Season of our warm Weather, and not expos’d abroad ‘till our Frosts began: For if we are to follow Nature in the Culture of Plants from hot Countries, we must so the same in the Management of those from the frozen Zone; we must imitate the Heat of one, and the Cold of the other.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 1:n.p.)[19]

- “I’CEHOUSE. n.s. [ice and house.] A house in which ice is reposited against the warm months.”

- Miller, Philip, 1759, The Gardeners Dictionary (1759: n.p.)[20]

- “Ice house is a Building contrived to preserve Ice for the Use of the family in the Summer Season. . . . It is considered that these Buildings are generally erected in Gardens. . . . The external wall need not be built circular, but of any other figure, either square, hexangular, or octangular, and where this stands much in Sight, it may be so contrived as to make it a good object. I have seen an Icehouse built in such a manner as to have had an alcove seat in the Front, and behind the Seat was contrived a passage to get in and put out ice.”

- Bordley, J. B., 1801, Essays and Notes on Husbandry and Rural Affairs (1801: 79)[21]

- “The Ice-House, will be best detached from the milk-house, that it may be clear of all moisture, and receive air on all sides. The ice-house at Gloster point, near Philadelphia, strongly recommends that it be chiefly above ground. Four feet under ground, six above ground and twelve square, would hold 1440 solid feet: which is enough for family and milk-house purposes, though very freely expended.”

- Moore, Thomas, 1803, An Essay on the Most Eligible Construction of Ice-houses (1803: 11)[22]

- “What is the most eligible construction for an Ice-house? . . .

- “The most favourable situation is a north hill side near the top. On such a site open a pit twelve feet square at top, ten at bottom and eight or nine feet deep: Logs may be laid round the top at the beginning, and the earth dug out raised behind them so as to make a part of the depth of the pit. A drain should be made at one corner.”

- Tudor, Frederic, 1806, “Outline of Proposals Respecting Ice” (quoted in Cummings 1949: 138)[23]

- “The ice-houses upon the old construction in Europe have become obsolete, they cost great sums and kept ice badly—those underground in this country kept it better by an improvement upon them without costing a tenth part as much—mine upon the same principle pursued further is an improvement upon them. . . . Moisture is the great destroyer of ice in ice-houses as it is a great conductor of heat from the surrounding bodies—all the moist air flies off from the top in my ice house and cannot communicate heat to the ice below because warm air cannot descend or cold air ascend.”

- Gregory, G. (George), 1816, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1816: 2:n.p.)[24]

- “ICE-HOUSE, a building contrived to preserve ice for the use of a family in the summer season. It is generally sunk some feet in the ground in a very shady situation, and covered with thatch.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 340)[25]

- “1725. The form of ice-houses commonly adopted at country-seats, both in Britain and in France, is generally that of an inverted cone, or rather hen’s egg, with the broad end uppermost.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 1:n.p.)[26]

- “ICEHOUSE, n. [ice and house.] A repository for the preservation of ice during warm weather; a pit with a drain for conveying off the water of the ice when dissolved, and usually covered with a roof.”

- Hooper, Edward James, 1842, The Practical Farmer, Gardener and Housewife (1842: 184)[27]

- “ICE HOUSE. In as warm a climate as this is in the summer season, ice for butter, milk, water, and other purposes, is a very great luxury. An ice house may be built under ground with or without any other building upon it. A dairy room or milk house may be built upon one.”

- Loudon, Jane, 1845, Gardening for Ladies (1845: 164)[28]

- “COLD HOUSES FOR PLANTS are not generally in use, though it is a common practice with gardeners to remove plants from hothouses into the back sheds, in order to retard their blossoming or the ripening of their fruit. It is also the practice in some countries to place pots of fruit-bearing or flowering shrubs in ice-houses, so as to keep them dormant through the summer. . . . Bulbs are also retarded in a similar manner; and even nosegays are placed in ice-houses in Italy and other warm countries, when it is wished to retard their decay for particular occasions.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, December 1846, “How to Build Ice-Houses” (Horticulturist 1: 249, 252–53)[29]

- “Our business at the present moment is with the Ice-house,—as a necessary and most useful appendage to a country residence. Abroad, both the ice-house and the hot-house are portions of the wealthy man’s establishment solely. But in this country, the ice-house forms part of the comforts of every substantial farmer. It is not for the sake of ice-creams and cooling liquors, that it has its great value in his eyes, but as a means of preserving and keeping in the finest condition, during the summer, his meat, his butter, his delicate fruit, and in short his whole perishable stock of provisions. . . .

- “An ice-house below ground is so inconspicuous an object, that it is easily kept out of sight, and little or no regard may be paid to its exterior appearance. On the contrary, an ice-house above ground is a building of sufficient size to attract the eye, and in many country residences, therefore, it will be desirable to give its exterior a neat or tasteful air. . . .

- “It will be frequently be found, however, that an ice-house above ground may be very conveniently constructed under the same roof as the wood-house, tool-house, or some other necessary out-building, following all the necessary details just laid down, and continuing one roof and the same kind of exterior over the whole building.

- “In places of a more ornamental character, where it is desirable to place the elevated ice-house at no great distance from the dwelling, it should, of course, take something of an ornamental or picturesque character.

- “In figures 63 and 64, (see FRONTISPIECE,) are shown two designs for ice-houses above ground, in picturesque styles. Figure 63 is built in a circular form, and the roof neatly thatched. The outside of this ice-house is roughly water-boarded, and then ornamented with rustic work, or covered with strips of bark neatly nailed on in pannels or devices. Two small gables with blinds ventilate the space under the roof.

- “Fig. 64 is a square ice-house, with a roof projecting three or four feet, and covered with shingles, the lower ends of which are cut so as to form diamond pattern when laid on the roof. The rustic brackets which support this roof, and the rustic columns of the other design, will be rendered more durable by stripping the bark off, and thoroughly painting them some neutral or wood tint.*[Fig. 7]

- “*The projecting roof will assist in keeping the building cool. In filling the house, back up the wagon loaded with ice, and slide the squares of ice to their places on a plank serving as an inclined plane.”

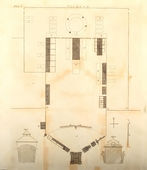

- Ranlett, William H., 1851, The Architect (1851; repr., 1976: 2:18)[30]

- “[Plate 12.—] Ground plot and profile of 1 1-4 acres of ground with the location of the Villa, A, B, and C; wood-house, D; privies, E E; Smokehouse, F; ash-house, G; ice-house, H; vegetable garden, I; coach-house, K; bath-house, L.” [Fig. 8]

Images

Inscribed

Thomas Jefferson, General plan of the summit of Monticello Mountain, before May 1768.

J. B. Bordley, “Section of an ice-pit,” in Richard Parkinson and J. B. Bordley, A Tour in America, 1798–1800, 2 vols. (1800), 2:699. Bordley cites this image as a “Section of an ice-pit, with its log-cell insulated with straw on all sides; and a house covering the whole.”

J. B. Bordley, Plan of a Farmyard, with details in section, in J. B. Bordley, Essays and Notes on Husbandry and Rural Affairs (1801), pl. I.

J. B. Bordley, Two Ice Houses Sected, in J. B. Bordley, Essays and Notes on Husbandry and Rural Affairs (1801), pl. II.

J. C. Loudon, Elevated circular platform to keep ice in stacks in Ice Houses, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 340, fig. 289.

J. C. Loudon, The form of Ice Houses and excavation of Ice-Wells, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 340, fig. 290.

J. C. Loudon, The construction of an Ice House, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 341, fig. 291.

Anonymous, “Two Ornamental Ice Houses Above Ground,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 1, no. 6 (December 1846): pl. opp. 249.

Anonymous, “Plan of a Suburban Villa Residence,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 118, fig. 26.

Frances Palmer, Plan and section of Villa at Oswego, New York, in William H. Ranlett, The Architect, 2 vols. (1851), vol. 2, pl. 12.

Frances Palmer, “Ground Plot,” in William H. Ranlett, The Architect, 2 vols. (1851), vol. 2, pl. 29.

Associated

Batty Langley, “An Improvement of a beautiful Garden at Twickenham,” in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. IX.

Charles Willson Peale, View of the garden at Belfield, 1816.

Attributed

Cornelius Tiebout, “A View of the present Seat of His Excel. the Vice President of the United States,” 1790.

Francis Guy, Perry Hall from the northwest, c. 1805.

Joseph Jacques Ramée, Estate plan for Calverton [detail], c. 1816, in Parcs & jardins (c. 1836), pl. 1.

Notes

- ↑ Helen Tangires, “Icehouses in America: The History of a Vernacular Building Type,” New Jersey Folklife 16 (1991): 37, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bordley’s design was the basis for Joseph Jacques Ramée’s “Détails d’une Glacière Américaine,” in Jardins irréguliers (Paris, 1823), pl. VIII, and in Allgemeine Bauzeitung (1854), pl. 652. See also Paul Venable Turner, Joseph Ramée: International Architect of the Revolutionary Era (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 236–37, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bentley, The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., 4 vols. (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), 4:36, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Tangires 1991, 39, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 John P. Riley, The Icehouses and Their Operations at Mount Vernon (Mount Vernon, VA: Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, 1989), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, 6 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1978), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constantia [Judith Sargent Murray], “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania,” The Massachusetts Magazine, or, Monthly Museum of Knowledge and Rational Entertainment 7, no. 3 (July 1791): 413–17, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels; in New-England and New-York, 4 vols. (New Haven: Timothy Dwight, 1821–22), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sir Augustus John Foster, Jeffersonian America: Notes on the United States of America Collected in the Years 1805–1806–1807 and 1811–1812, ed. Richard Beale Davis (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1954), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Martha Ogle Forman, Plantation Life at Rose Hill: The Diaries of Martha Ogle Forman, 1814–1845 (Wilmington: Historical Society of Delaware, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. S. Williams, “Ice Houses—With Ice Closets Attached,” New England Farmer 2, no. 16 (November 15, 1823): 125, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Saunders and Helen Raye, Daniel Wadsworth, Patron of the Arts (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1981), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Q., “On Ice-Houses,” New England Farmer 5, no. 22 (December 22, 1826): 173, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frances Milton Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (London: Wittaker, Treacher & Co., 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Ice and Ice-Houses,” New England Farmer, and Gardener’s Journal 13, no. 45 (May 20, 1835): 353–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Bradley, New Improvements of Planting and Gardening, Both Philosophical and Practical . . . 3rd ed., 2 vols. (London: W. Mears, 1719), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Philip Miller, The Gardeners Dictionary: Containing the Methods of Cultivation and Improving the Kitchen, Fruit, and Flower Garden . . . 7th ed. (London: Philip Miller, 1759), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. B. [John Beale] Bordley, Essays and Notes on Husbandry and Rural Affairs, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1801), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Moore, An Essay on the Most Eligible Construction of Ice-Houses (Baltimore: Bonsal and Niles, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard O. Cummings, The American Ice Harvests: A Historical Study in Technology, 1800–1918 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1949), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Gregory, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences 1st American ed., 3 vols. (Philadelphia: Isaac Peirce, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward James Hooper, The Practical Farmer, Gardener and Housewife, or Dictionary of Agriculture, Horticulture, and Domestic Economy (Cincinnati, OH: George Conclin, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden, ed. A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “How to Build Ice-Houses,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 1, no. 6 (December 1846): 249–53, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William H. Ranlett, The Architect, 2 vols. (1849–51; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1976), view on Zotero.