Difference between revisions of "Cemetery/Burying ground/Burial ground"

A-Whitlock (talk | contribs) |

A-Whitlock (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 296: | Line 296: | ||

File:1142.jpg|John Caspar Wild, ''Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia'', 1838. | File:1142.jpg|John Caspar Wild, ''Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia'', 1838. | ||

| − | File:0568.jpg|William Keenan, ''Plan of the City and Neck of Charleston, S.C.'', September 1844. | + | File:0568.jpg|William Keenan, ''Plan of the City and Neck of Charleston, S.C.'', September 1844. The "public cemetery" is located in the center left, above the "marsh". |

File:1170.jpg|E. J. Pinkerton, ''General View of Laurel Hill Cemetery'', 1844. | File:1170.jpg|E. J. Pinkerton, ''General View of Laurel Hill Cemetery'', 1844. | ||

Revision as of 16:37, February 24, 2020

History

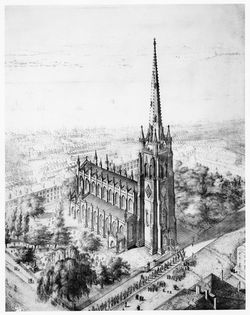

In the late 18th century, three primary types of burial places existed: land adjoining a church (often termed the “churchyard,” but also called a cemetery or burial ground) [Fig. 1], the family plot at one’s home (the burying ground), and public space that was unaffiliated with any specific denomination.[1] This latter type was also denoted as a “burying ground” but most commonly was labeled as a cemetery.[2] Initially located in central urban areas such as commons, by the 19th century public burial grounds were increasingly located in suburban precincts. As late as 1724 (and perhaps long after) New Englanders “valued graveyards more as meadows than as sacred spaces,” and, in the public’s mind, graveyards were regarded as “common, if not hallowed ground,” according to historian David Charles Sloane.[3] The word “cemetery,” which “derived from the Greek word for ‘dormitory’ and implied that death was but a tranquil sleep,” reflected the increasing sentimentalization of death and the Protestant theological shift from punitive to redemptive interpretations of death.[4] Notably, the terms “burying ground” and “churchyard” were not completely phased out with the introduction of rural cemeteries and continued to be used interchangeably.[5] Although the term “cemetery” was often associated with rural park-like spaces, it also referred to enclosed burial grounds, such as the one described in 1796 by Timothy Dwight in New Haven, Connecticut.

The New Haven Burying Ground, as it was originally named, was one of the earliest burial places to be located out side the main commercial district of a town [Fig. 2]. Concerns about public health stemming from overcrowded urban burial places, the development of romantic discourse on the emotional impact of natural scenery, and anxieties about appropriate veneration of the dead resulted in a movement to relocate burial grounds from congested urban sites to more rural settings.[6] Observers of the New Haven Burying Ground, including Dwight, praised the proprietors for their orderly and well laid out grounds based upon a geometric plan, with each fenced lot fashioned in the shape of a parallelogram. The division of the landscape was carried over into the placement of the city’s various populations—the poor, Yale affiliates, strangers, and “negroes”—into clearly defined, separate spaces. As such, New Haven Burying Ground became a model for other cities. Nevertheless, some writers, such as Rev. Nehemiah Adams (1842), continued to argue for the use of urban plots in the belief that the dead should be permitted to commune with the “joyous events” of the city.

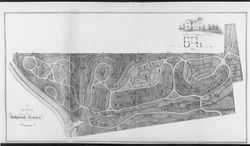

The archetypal 19th-century burial ground, however, was Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, founded in 1831 on the grounds of a former estate called “Sweet Auburn.”[7] The founders of the so-called rural cemetery originally envisioned combining an “experimental” or botanic garden with a burying ground. Given the precedent for a garden cemetery that was set by the famed Père Lachaise (founded in Paris in 1804) and the influence of English landscape gardens upon botanic garden designs of this period, it is not surprising that the planners of Mount Auburn Cemetery desired a rural, naturalistic design.[8] They left much of the original grounds and vegetation intact and landscaped the grounds with the introduction of avenues, walks, and waterways [Figs. 3 and 4]. The boundaries of the cemetery were intended to blend into the grounds of the experimental garden through intermingled vegetation and meandering avenues. Throughout the grounds, picturesque views rewarded the visitor. Instead of the regimented landscape at the New Haven Burying Ground, Mount Auburn Cemetery embraced openness, created by the use of serpentine pathways and carefully placed vegetation, which could both screen and create vistas. The actual grave sites, however, were still bounded by iron railings to mark a zone of respect for the dead [Fig. 5].

Although the Mount Auburn Cemetery planners quickly were forced to discard their plans for an experimental garden, they fulfilled their vision of a rural, picturesque, park-like landscape.[9] It became the model for a number of subsequent cemeteries, such as Spring Grove Cemetery (Cincinnati), Laurel Hill Cemetery (Philadelphia), and Greenwood Cemetery (Brooklyn), and it earned the praise of such critics as A. J. Downing.[10] Even without the existence of a botanic garden, the superintendents of Mount Auburn Cemetery were able to lavish much attention on ornamental plantings. It is worth noting that extensive discussions about the ornamentation of burial places with plant material and other landscape features did not generally appear in treatise literature about the sites until the popularization of rural cemeteries in the 19th century.

As Downing pointed out in his 1849 essay “Public Cemeteries and Public Gardens,” Mount Auburn Cemetery also had “the double wealth of rural and moral associations . . . it awakens, at the same moment, the feeling of human sympathy and the love of natural beauty.” The rural setting, with its suggestions of the sublime, enhanced the experience of mourning for one’s loved ones. The space was also an educational tool, providing exemplary taste in planting arrangements, as well as a guide to American history through the monuments to “illustrious men,” as described by H. A. S. Dearborn (1832).

Burial monuments found on the grounds contributed to the emotional impact of Mount Auburn Cemetery’s “romantic” and “picturesque” scenery. Obelisks and other ancient style markers, for example, gave rise to associations with classical heroes (see Column). The entrance gates, executed in the Egyptian style, were associated with the notion that “eternity was evoked by the massive forms.” Such grand gateways were also found at the New Haven Burying Ground.[11]

By the time Downing wrote his 1849 essay about public cemeteries and gardens, Greenwood Cemetery, Mount Auburn Cemetery, and Laurel Hill Cemetery had established a norm in cemetery design that influenced later designs [Figs. 6 and 7]. Although burial grounds did not require natural scenery to be effective places for “solemn meditation,” in Downing’s words, rural cemeteries fulfilled a vital niche in American life. They created rural pleasure grounds where Americans could witness the beauty of nature enhanced by art. In the absence of public gardens or parks, cemeteries were the next best thing—educating “the popular taste in rural embellishment.”

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Oldmixon, John, 1741, describing Charleston, SC (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 67)[12]

- “[An act established that Charleston was to] be a distinct Parish, by the Name of St. Philip’s in Charles-Town: And the Church and Cemetery of this Town were enacted to be the Parish Church and Church-yard of St. Philip’s in Charles-Town.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1771, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1944: 25)[13]

- “. . . choose out for a Burying place some unfrequented vale in the park, where is, ‘no sound to break the stillness but a brook, that bubbling winds among the weeds; no mark of any human shape that had been there, unless the skeleton of some poor wretch, Who sought that place out to despair and die in.’ let it be among antient [sic] and venerable oaks; intersperse some gloomy evergreens. the area circular, abt. 60 f. diameter, encircled with an untrimmed hedge of cedar, or of stone wall with a holly hedge on it in the form below. in the center of it erect a small Gothic temple of antique appearance. appropriate one half to the use of my own family, the other of strangers, servants, etc. erect pedestals with urns, etc., and proper inscriptions. the passage between the walls, 4 f. wide. on the grave of a favorite and faithful servant might be a pyramid erected of the rough rock-stone; the pedestal made plain to receive inscription. let the exit of the spiral. . . look on a small and distant part of the blue mountains. in the middle of the temple an altar, the sides of turf, the top of plain stone. very little light, perhaps none at all, save only feeble ray of an half extinguished lamp.”

- Anonymous, 1789 , describing in the Christ Church Parish Book plans for expanding the public cemetery in Savannah, GA (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 67)[12]

- “[Plans have been made] for enlarging the present Cemetery or Public Burial Ground.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing New Haven Burying Ground, New Haven, CT (1821: 1:191)[14]

- “While the Romish apprehension concerning consecrated burial-places, and concerning peculiar advantages, supposed at the resurrection to attend those, who are interred in them, remained; this location of burial-grounds [or yards located behind a church that was set in a public square] seems to have been not unnatural. But, since this apprehension has been perceived by common sense to be groundless and ridiculous, the impropriety of such a location forces itself on every mind. It is always desirable, that a burial-ground should be a solemn object to man; because in this manner it easily becomes a source of useful instruction and desirable impressions. But, when placed in the centre of a town, and in the current of daily intercourse, it is rendered too familiar to the eye to have any beneficial effect on the heart. From its proper, venerable character, it is degraded into a mere common object; and speedily loses all its connection with the invisible world, in a gross and vulgar union with the ordinary business of life.” [See Fig. 2]

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing the New Haven Burying Ground, New Haven, CT (1821: 1:190–92)[14]

- “Indubitable proofs of the enterprise of the inhabitants are seen in the Institutions already mentioned. . . Of these, levelling and enclosing the green, accomplished by subscription, at an expense of more than two thousand dollars, and the establishment of a new public cemetery, accomplished at a much greater expense, are particularly creditable to their spirit.

- “The original settlers of New-Haven, following the custom of their native country, buried their dead in a Church-yard. Their Church was erected on the green, or public square; and the yard laid out immediately behind it in the North-Western half of the square. . . It is always desirable, that a burial-ground should be a solemn object to man; because in this manner it easily becomes a source of useful instruction and desirable impressions. But, when placed in the centre of a town, and in the current of daily intercourse, it is rendered too familiar to the eye to have any beneficial effect on the heart. From its proper, venerable character, it is degraded into a mere common object; and speedily loses all its connection with the invisible world, in a gross and vulgar union with the ordinary business of life.

- “Besides these disadvantages, this ground was filled with coffins, and monuments, and must either be extended farther over the beautiful tract, unhappily chosen for it, or must have its place supplied by a substitute. To accomplish these purposes, and to effectuate a removal of the numerous monuments of the dead, already erected, whenever the consent of their survivors could be obtained; the Honourable James Hillhouse, one of the inhabitants, to whom the town, the State, and the country, owe more than to almost any of their citizens, in the year 1796, purchased, near the North-Western corner of the original town, a field of ten acres; which, aided by several respectable Gentlemen, he levelled, and enclosed. The field was then divided into parallelograms, handsomely railed, and separated by alleys of sufficient breadth to permit carriages to pass each other. . . Each parallelogram is sixty-four feet in breadth, and thirty-five feet in length. Each family burying-ground is thirty-two feet in length and eighteen in breadth: and against each an opening is made to admit a funeral procession. At the divisions between the lots trees are set out in the alleys: and the name of each proprietor is marked on the railing. The monuments in this ground are almost universally of marble; in a few instances from Italy; in the rest, found in this and neighbouring States. A considerable number are obelisks; others are tables; and others, slabs, placed at the head and foot of the grave. The obelisks are placed, universally, on the middle line of the lots; and thus stand in a line, successively, through the parallelograms. The top of each post, and the railing, are painted white; the remainder of the post, black. . .

- “It is believed, that this cemetery is altogether a singularity in the world. I have accompanied many Americans, and many Foreigners, into it; not one of whom had ever seen, or heard, of any thing [sic], of a similar nature. It is incomparably more solemn and impressive than any spot, of the same kind, within my knowledge; and, if I am to credit the declarations of others, within theirs. An exquisite taste for propriety is discovered, in every thing belonging to it; exhibiting a regard for the dead, reverential, but not ostentatious, and happily fitted to influence the views, and feelings of succeeding generations.” [See Fig. 2]

- Weld, Isaac, 1799, describing Norfolk County, VA (1799: 101–2)[15]

- “A custom prevails in Norfolk, of private individuals holding grave yards, which are looked upon as a very lucrative kind of property, the owners receiving considerable fees annually for giving permission to people to bury their dead in them. It is very common also to see, in the large plantations in Virginia, and not far from the dwelling house, cemeteries walled in, where the people of the family are all buried. These cemeteries are generally built adjoining the garden.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1799, describing Stockbridge, MA (1822: 3:408)[14]

- “On our way to Stockbridge we went to the Indian monument, mentioned in a former part of these letters; and, to our great regret, found it broken up in the same manner, as that at New-Milford.

- “I ought, in my account of that, to have added, that this mode of erecting monuments was adopted only on peculiar occasions. The common manner of Indian burial had nothing in it of this nature. The remains of the dead, who died at home, were lodged in a common cemetery, belonging to the village, in which they had lived.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1800, describing Guilford, CT (Solomon, ed., 1969: 2:360)[16]

- “This square, like that in New Haven, is deformed by a burying ground, and to add to the deformity is unenclosed. . .

- “The design of locating places of burial in this manner was probably good. In its execution, however, it evidently defeats itself, while it is also a plain violation of propriety. Instead of producing those solemn thoughts and encouraging those moral propensities which it was intended to inspire, it renders death and the grave such familiar objects to the eye as to prevent them from awakening any serious regard. . . Nor is it unreasonable to suppose that the proximity of these sepulchral fields to human habitations is injurious to health. Some of them have, I believe, been found to be offensive and will probably be allowed to have been noxious. Even in cases where nothing of this nature is perceptible, it is far from being clear that effluvia, too subtle to become an object of sense, do not ascend in sufficient quantities to affect with disease, or at least with a predisposition to disease, those who by living in the neighborhood are continually breathing this mischievous exhalation.”

- Lambert, John, 1816, describing New York, NY (1816: 2:88)[17]

- “The church-yards and vaults are also situate [sic] in the heart of the town, and crowded with the dead. If they are not prejudicial to the health of the people, they are at least very unsightly exhibitions. One would think there was a scarcity of land in America, by seeing such large pieces of ground in one of the finest streets of New York occupied by the dead. But even if no noxious effluvia were to arise (and I rather suspect there must in the months of July, August, and September), still the continual view of such a crowd of white and brown tomb-stones and monuments which is exhibited in the Broadway, must at the sickly season of the year tend very much to depress the spirits, when they should rather be cheered and enlivened, for at that period much is effected by the force of imagination. There is a large burying-ground a short distance out of town; but the cemeteries in the city are still used in certain periods of the year.”

- Lambert, John, 1816, describing Savannah, GA (1816: 2:267)[17]

- “A large burying-ground is judiciously situated out of town, upon the common. It is inclosed by a brick wall, and contains several monuments and tomb-stones, which are shaded by willows and pride of India; and have a very pretty effect. This cemetery, though now a considerable distance from the town, will, in time, most probably, be surrounded by the dwellings of the inhabitants, like those of New York and Charleston.”

- Anonymous, 1823, describing in the St. Philips Parish Vestry Book a burial request made to the St. Philips Parish, Charleston, SC (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 67)[12]

- “[At a meeting of the vestry] a letter from E. S. Garden & B. Bamfield (persons of Colour) were presented. . . wishing to know whether the Vestry would permit their remains to be interred in the Cemetery of the Church at some future day.”

- Fessenden, Thomas Green, January 25, 1823, “National Burying Ground” (New England Farmer 1: 206)[18]

- “This cemetery is in a remote and lonely situation, being something more than a mile in a southeasterly direction from the Capitol. It lies immediately upon the bank of East Branch, at the distance of only a few yards from the water’s edge, but elevated considerably above it, and commanding an extensive view of the river. The winding path leading to it is over a wide and barren common—there are no houses in the vicinity—and it will be long before it will be in the midst of the city. Had the churchyards of New-York been laid out with the same precaution, they would not now have formed a subject of legislation for the Common Council, nor for newspaper discussion. This grave-yard contains an area of two or three acres, enclosed by a plain wooden fence, and sprinkled with copses of native cedar, stinted in their growth and many of them withered, either from the poverty of the soil, or from having their roots broken by the spade of the grave-digger. There are however, enough living to conceal many of the graves; and their verdure, contrasted with the grey tomb stones produces an agreeable effect.”

- Anonymous, September 29, 1825, describing in the St. Philip’s Parish Vestry Book meeting resolutions made in Charleston, SC (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “That social feeling & sense of propriety which induce the Vestry to keep their Cemetery neat & private, require them also to consult appearances, even in such solemn matters as the burial of Memorials of the dead, for the inscriptions perish long before the wood itself & then unseemly Appearances is a sufficient reason for excluding them. . .

- “The practice of appropriating certain portions of the Church yard as Family burial grounds, by means of Vaults and palings, seems to be of very ancient date & probably was almost with the use of the church. In order to abolish the latter mode the Vestry ordered on the 14th October 1767 (that persons who had enclosures in the church yard should not be allowed to repair them.). . . On the 27th July 1800 the Vestry resolved that should application be made for leave to erect a Monument in the Churchyard, the vestry shall only allow a tablet against the wall, or a headstone not exceeding 4 1/2 feet in length-1 foot 10 inches in breadth and 3 1/2 inches in thickness.”

- Douglass, Frederick, 1825, describing Wye House, estate of Col. Edward Lloyd, Talbot County, MD (1987: 48)[19]

- “A short distance from the great house, were the stately mansions of the dead, a place of somber aspect. Vast tombs, embowered beneath the weeping willow and the fir tree, told of the antiquities of the Lloyd family, as well as of their wealth. Superstition was rife among the slaves about this family burying ground. Strange sights had been seen there by some of the older slaves. Shrouded ghosts, riding on great black horses, had been seen to enter; balls of fire had been seen to fly there at midnight, and horrid sounds had been repeatedly heard. Slaves know enough of the rudiments of theology to believe that those go to hell who die slaveholders; and they often fancy such persons wishing themselves back again, to wield the lash. Tales of sights and sounds, strange and terrible, connected with the huge black tombs, were a very great security to the grounds about them, for few of the slaves felt like approaching them even in the day time. It was a dark, gloomy and forbidding place, and it was difficult to feel that the spirits of the sleeping dust there deposited, reigned with the blest in the realms of eternal peace.”

- Anonymous, April 17, 1829, “Neglected Grave Yards” (New England Farmer 7: 307)[20]

- “I wish to call your attention to the subject of repairing, clearing, and ornamenting the burial grounds of New England. These enclosures are commonly neglected by the sexton, and present to the curious traveller, an ugly collection of slate slabs, of weeds, and rank or dried grass. A small effort in each sexton or clergyman, would suffice to awaken attention, to bring to the recollection of some, and to the fancy of all, a scene which every village should present, a grove sacred to the dead and to their recollection, to calm religious conversation, and to melancholy musing—inclosed with shrubbery, and evergreen, and dignified by the lofty maple, and elm, and oak, and guarded by a living hedge of hawthorn.

- “Every sexton should procure some oak, elm, and locust seed, and make it a part of his vocation to scatter it for chance growth.”

- Story, Joseph, September 24, 1831, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (1831: 16–17)[21]

- “A rural Cemetery seems to combine in itself all the advantages, which can be proposed to gratify human feelings, or tranquillize human fears; to secure the best religious influences, and to cherish all those associations, which cast a cheerful light over the darkness of the grave.

- “And what spot can be more appropriate than this for such a purpose? Nature seems to point it out with significant energy, as the favorite retirement for the dead. There are around us all the varied features of her beauty and grandeur—the forest-crowned height; the abrupt acclivity; the sheltered valley; the deep glen; the grassy glade; and the silent grove. Here are the lofty oak, the beech, that ‘wreaths its old fantastic roots so high,’ the rustling pine, and the drooping willow; —the tree, that sheds its pale leaves with every autumn,a fit emblem of our own transitory bloom; and the evergreen, with its perennial shoots, instructing us, that ‘the wintry blast of death kills not the buds of virtue.’ Here is the thick shrubbery to protect and conceal the new-made grave; and there is the wild-flower creeping along the narrow path, and planting its seeds in the upturned earth. All around us there breathes a solemn calm, as if we were in the bosom of a wilderness, broken only by the breeze as it murmurs through the tops of the forest, or by the notes of the warbler pouring forth his matin or his evening song.”

- Dearborn, H. A. S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Harris 1832: 63–65, 67–68)[22]

- “With the Experimental Garden it is recommended to unite a Rural Cemetery; for the period is not distant, when all the burial grounds within the city will be closed, and others must be formed in the country,—the primitive and only proper location. There the dead may repose undisturbed, through countless ages. There can be formed a public place of sepulture, where monuments can be erected to our illustrious men, whose remains, thus far, have unfortunately been consigned too obscure and isolated tombs, instead of being collected within one common depository, where their great deeds might be perpetuated and their memories cherished by succeeding generations.Though dead, they would be eternal admonitors to the living,—teaching them the way which leads to national glory and individual renown. . .

- “For the accommodation of the Garden of Experiment and Cemetery, at least seventy acres of land are deemed necessary; and in making the selection of a site, it was very important that from forty to fifty acres should be well or partially covered with forest trees and shrubs, which could be appropriated for the latter establishment; and that it should present all possible varieties of soil, common in the vicinity of Boston; be diversified by hills, valleys, plains, brooks, and low meadows and bogs, so as to afford proper localities for every kind of tree and plant, that will flourish in this climate;—be near to some large stream or river; and easy of access by land and water; but still sufficiently retired.

- “To realize these advantages it is proposed, that a tract of land called ‘Sweet Auburn,’ situated in Cambridge, should be purchased. As a large portion of the ground is now covered with trees, shrubs, and wild flowering plants, avenues and walks may be made through them, in such a manner as to render the whole establishment interesting and beautiful, at a small expense, and within a few years; and ultimately offer an example of landscape or picturesque gardening, in conformity to the modern style of laying out grounds, which will be highly creditable to the Society. . .

- “The establishment of rural cemeteries similar to that of Pere La Chaise, has often been the subject of conversation in this country, and frequently adverted to by the writers in our scientific and literary publications. . .

- “That part of the land which has been recommended for a Cemetery may be circumvallated by a spacious avenue bordered by trees, shrubbery, and perennial flowers; rather as a line of demarcation than of disconnexion; for the ornamental grounds of the Garden should be apparently blended with those of the Cemetery, and the walks of each so intercommunicate as to afford an uninterrupted range over both, as one common domain.

- “Among the hills, glades, and dales, which are now covered with evergreen and deciduous trees and shrubs, may be selected sites for isolated graves, and tombs, and these, being surmounted with columns, obelisks, and other appropriate monuments of granite and marble, may be rendered interesting specimens of art; they will also vary and embelish the scenery embraced within the scope of the numerous sinuous avenues, which may be felicitously opened in all directions and to a vast extent, from the diversified and picturesque features which the topography of the tract of land presents.”

- Martineau, Harriet, 1834, describing a cemetery in New Orleans, LA (1838: 2:228–29)[23]

- “Before visiting Mount Auburn I had seen the Catholic cemetery at New-Orleans, and the contrast was remarkable enough. I never saw a city churchyard, however damp and neglected, so dreary as the New-Orleans cemetery. It lies in the swamp, glaring with its plastered monuments in the sun, with no shade but from the tombs. Being necessarily drained, it is intersected by ditches of weedy stagnant water, alive with frogs, dragonflies, and moscheto-hawks [sic]. Irish, French, and Spanish are all crowded together, as if the ground could scarcely be opened fast enough for those whom the fever lays low; an impression confirmed by a glance at the dates. The tombs of the Irish have inscriptions which provoke a kind of smile, which is no pleasure in such a place. Those of nuns bear no inscription but the monastic name—Agathe, Seraphine, Thérèse—and the date of death. Wooden crosses, warped in the sun or rotting with the damp, are in some places standing at the heads of graves, in others are leaning or fallen. Glass boxes, containing artificial flowers and tied with faded ribands, stand at the foot of some of these crosses. Elsewhere we saw pitchers with bouquets of natural flowers, the water dried up and the blossoms withered. One enclosure surrounding a monument was adorned with cypress, arbour vitae, roses, and honeysuckles, and this was a relief to the eye while the feet were treading the hot dusty walks or the parched grass. The first principle of a cemetery was here violated, necessarily, no doubt, but by a sad necessity. The first principle of a cemetery—beyond the obligation of its being made safe and wholesome—is that it should be cheerful in its aspect.”

- B., J., October 1, 1836, “Horticulture in Maine,” describing Mount Hope Cemetery, Bangor, ME (Horticultural Register 2: 386)[24]

- “Mount Hope cemetery is in imitation of Mount Auburn, and was consecrated the present season. It contains thirteen acres mostly on a steep, conical hill, ornamented by nature with evergreen and other trees. The avenues and walks have been laid out under the direction of Dr Barstow and are either completed or in a state of forwardness. At the foot of the hill is a small run or brook, across which a dam has been built and a pond raised. Passing thus by a neat bridge, we enter another lot of ten acres, which has been purchased by the city for a public burial ground, and the whole is about to be inclosed by a substantial fence in one piece.”

- Adams, Rev. Nehemiah, 1838, describing Copp’s Hill Burying Ground, Boston, MA (1838: 24)[25]

- “And were it not for the fact, that cemeteries are very injudiciously allowed in cities, we should advert with pleasure to the walks afforded by the Copp’s Hill burying-ground—wanting only a grove of ancient trees to render it delightful.”

- Anonymous, 1839, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (1839: 3)[26]

- “The celebrity attained by Mount Auburn, pronounced by European travellers the most beautiful Cemetery in existence, and which, perhaps, without assuming too much, may be called the Père la Chaise of America,—the extraordinary natural loveliness of the spot,—the admirable character of the establishment which is there maintained,—the fact that this was the first conspicuous example of the kind in our country.”

- Willis, Nathaniel Parker, 1840, describing New Haven Burying Ground, New Haven, CT (1840: 220)[27]

- “To the enterprise of the same public-spirited gentleman [Honorable James Hillhouse], New Haven owes one of the most beautiful cemeteries in the world. The square in the rear of the churches was formerly, according to the English custom, used as a churchyard, and encumbered with graves, which soon threatened to overrun its limits. Mr. Hillhouse, some years since, purchased a field in the western skirt of the town, laid it out and planted it, and subsequently removed to it all the tombstones and remains from the Green; among them the headstone of the regicide Goffe. It is now one of the most beautiful of burial-places. The monuments are of white marble, or of a very rich verd antique found in the neighbourhood; and the natural elegance of the place has induced a taste and elegance into these monuments for the dead, found in no other spot of the same character.”

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1841, describing Vermont (1841: 2:275)[28]

- “We observed, also, that to many of the isolated dwelling-houses in the country there were private burial-grounds attached, in which one or two members of the family had been interred; and the place of their repose was marked by a neat monument within an enclosure, just as if it had been included within consecrated ground.”

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1841, describing Rochester, NY (1841: 2:215)[28]

- “A large piece of ground on the east of the river and south of the city, seated on a pleasing eminence, has also been recently devoted to the purpose of a public cemetery, to supersede all the smaller ones; and the intention is to plant it with ornamental shrubs and lay it out in walks, so as to make it as agreeable as Laurel Hill at Philadelphia, or Mount Auburn at Boston.”

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1841, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (1841: 2:382)[28]

- “A comparison has been often made between the Père la Chaise of Paris and the Mount Auburn of Boston, and the similarity of their situation and their purpose naturally forces this comparison on the mind. Having seen both, I may venture to offer an opinion on this subject, with great deference, however, to those who may think otherwise. In many respects, then, I think Mount Auburn superior to Père la Chaise. Its natural scenery of hill and dale, of river, lake, and forest-trees, with other surrounding objects, presents a combination which is not to be found in the cemetery of Paris, and which is far more in harmony with the repose of the dead than the most sumptuous monuments, without these combinations, can be. In this last respect Père la Chaise is perhaps unrivalled.”

- Adams, Rev. Nehemiah, 1842, describing Boston Common, Boston, MA (1842: 57)[29]

- “The burying-places in the vicinity of the Common, with that in its southern border, are fast becoming desolate places in appearance by the rapid growth of wild bushes and rank grass amongst the headstones. The sumac, and larch, and willow, and elm saplings, and running vines, are tangling the granary burying-ground in beautiful confusion. It is good taste to let it be so, and we thank those who suffer this wild pall of nature to rest upon those graves. If interments must continue to be made in the city, let the places of burial be veiled as much as possible with spontaneous verdure; it is due to the feelings of those who live in a city that the exposed places of the dead should be divested of their hideous appearance. . . But the tendency of the public taste is evidently towards such places as Mount Auburn. Yet there is something pleasant in the thought of being interred in a city. We cannot help associating the dead who lie in the burial-place on the Common with the exciting and joyous events which take place around their graves. It seems as though they were witnesses of things which interest the world about them, while they are free from any share in human labors and sorrows. Their quiet resting places, responsive to no sights or sounds, are in impressive contrast with the multitudes who throng the Common on public days, and pour along the malls on Sabbath evenings, in busy conversation about their plans and sorrows and joys.”

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1842, describing Wythe County, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Soon after our setting out, we observed in the fields a large sycamore-tree, with wide-spreading branches, enclosed with a neat palisade, and was told that this was a very usual way of forming a rustic cemetery, which was confirmed by our seeing several graves within the enclosure.”

- W., February 1842, “An Account of the Lowell Cemetery,” Lowell, MA (Magazine of Horticulture 8: 47–48)[30]

- “The Lowell Cemetery contains an area of about forty-four acres of land, retired, and pleasantly situated on the southern slope of ‘Fort Hill,’ and at the distance of about three quarters of a mile from the city, and a mile and half from the City Hall. The surface of the ground is beautifully diversified with hill and valley. . .

- “With such variety of surface, this ground possesses a high degree of adaptation as a place of sepulture; and ornamented both by nature and art, this cemetery must have attractions for the most unobserving and the least reflecting. There are many historical associations connected with this spot, and its former, but now long deceased, occupants.”

- Bryant, William Cullen, April 7, 1843, describing Savannah, GA (quoted in Clarke 1993: 2:155)[31]

- “In the same neighborhood [south of the town], just without the town, lies the public cemetery, surrounded by an ancient wall, built before the Revolution, which in some places shows the marks of shot fired against it in the skirmishes of that period. . . At a little distance, near a forest, lies the burial-place of the black population. A few trees, trailing with long moss, rise above hundreds of nameless graves, overgrown with weeds; but here and there are scattered memorials of the dead, some of a very humble kind, with a few of marble, and half a dozen spacious brick tombs like those in the cemetery of the whites.”

- Trego, Charles, 1843, describing Chambersburg, PA (1843: 249)[32]

- “The Presbyterian church is much admired on account of its beautiful situation in a retired quiet spot, enveloped with trees and surrounded by a delightful green, at the west end of which is the burying ground of the congregation, and adjoining it, an ancient burying ground of the Indians.”

- Trego, Charles, 1843, describing Philadelphia (1843: 319)[32]

- “Washington square, on Sixth street between Walnut and Locust, was for many years used as a public burial ground for the poor and for strangers, under the name of the Potters’ field.”

- Tuthill, Louisa C. (Louisa Caroline), 1848, describing New Haven Burying Ground, New Haven, CT (1848; repr. 1988: 337)[33]

- “The ‘burying-ground’ at New Haven, Connecticut, has long been celebrated for its beauty. It has recently been enclosed with a massive wall on three sides, and a bronzed iron fence in front. The entrance is of free-stone, in the Egyptian style. (Plate XXXIII.) H. Austin architect.” [Fig. 8]

- Tuthill, Louisa C. (Louisa Caroline), 1848, describing Greenwood Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY (1848; repr., 1988: 337)[33]

- “Greenwood Cemetery near New York, is beautifully situated, and contains many magnificent monuments.” [Fig. 9]

- Tuthill, Louisa C. (Louisa Caroline), 1848, describing Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia, PA (1848; repr. 1988: 337–38)[33]

- “Laurel Hill, on the banks of the Schuylkill, is another rural cemetery, consecrated to the repose of the dead, by the citizens of Philadelphia. ‘Every mind capable of appreciating the beautiful in nature, must admire its gentle declivities, its expansive lawns, its hill beetling over the picturesque stream, its rugged ascents, its flowery dells, its rocky ravines, and its river-washed borders.’”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, July 1849, “Public Cemeteries and Public Gardens” (Horticulturist 4: 9–10)[34]

- “The great attraction of these cemeteries, to the mass of the community, is not in the fact that they are burial places, or solemn places of meditation for the friends of the deceased, or striking exhibitions of monumental sculpture, though all these have their influence. All these might be realized in a burial ground, planted with straight lines of willows, and sombre avenues of evergreens. The true secret of the attraction lies in the natural beauty of the sites, and in the tasteful and harmonious embellishment of these sites by art. Nearly all these cemeteries were rich portions of forest land, broken by hill and dale, and varied by copses and glades, like Mount Auburn and Greenwood, or old country seats, richly wooded with fine planted trees, like Laurel Hill. Hence, to the inhabitant of the town, a visit to one of these spots has the united charm of nature and art,—the double wealth of rural and moral associations. It awakens, at the same moment, the feeling of human sympathy and the love of natural beauty, implanted in every heart. His must be a dull or a trifling soul that neither swells with emotion, or rises with admiration, at the varied beauty of these lovely and hallowed spots.

- “Indeed, in the absence of great public gardens, such as we must surely one day have in America, our rural cemeteries are doing a great deal to enlarge and educate the popular taste in rural embellishment. They are for the most part laid out with admirable taste; they contain the greatest variety of trees and shrubs to be found in the country, and several of them are kept in a manner seldom equalled in private places. . .

- “The character of each of the three great cemeteries is essentially distinct. Greenwood, the largest, and unquestionably the finest, is grand, dignified, and park-like. It is laid out in a broad and simple style, commands noble ocean views, and is admirably kept. Mount Auburn is richly picturesque, in its varied hill and dale, and owes its charm mainly to this variety and intricacy of sylvan features. Laurel Hill is a charming pleasure-ground, filled with beautiful and rare shrubs and flowers; at this season, a wilderness of roses, as well as fine trees and monuments.” [Fig. 10]

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1850, describing cemeteries in America (1850: 333)[35]

- “857. Cemeteries. . .

- “A public cemetery was formed in 1831 at Mount Auburn, about three miles from Boston, and is easily approached either by the road, or the river which washes its borders. . . . ‘This romantic and picturesque cemetery,’ says Dr. Mease, ‘is the fashionable place of interment with the people of Boston.’ . . .

- “Cemeteries at Philadelphia. ‘Laurel Hill is about three miles and a half north of the city, on the river Schuylkill. The part devoted to interments embraces about twenty acres, and is laid out in the most tasteful manner. The entrance is a specimen of Doric architecture, through which is a pleasing vista, and on each side are lodges for the accommodation of the gravedigger and gardener; and within is a neat cottage for the superintendent, a Gothic chapel for funeral service, a large dwelling-house for visiters [sic], a handsome receiving tomb, stabling for forty carriages, and a greenhouse. Besides the native forest trees on the place, several hundred more, and many ornamental shrubs, have been planted. The lots are enclosed by iron railings.’ . . . (Dr. Mease in the Gard. Mag., for 1843, p. 666.). . .

- “The cemetery of the Episcopal church of the town of Guildford is in a public square, and uninclosed. The graves are, therefore, trampled upon, and the monuments injured, both by men and cattle.”

- Anonymous, May 13, 1850, describing in the St. Stephen’s Parish Vestry Book the preservation of burial grounds in Berkeley County, SC (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “7th Resolved that out of the first money accruing from the interest of the church fund or from the benevolence of Individual Donors, it shall be the duty of the Trustees then in office to enclose the church and all the ground about it for the purpose of a Public Burying yard with a wide & deep ditch & a high and well-formed embankment on three sides of the Church, leaving the side bounding on the public river road open and free of access to the public, and such cemetery shall always be free to the uses of such persons as may desire to use it for that purpose, &c.”

Citations

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 1:n.p.)[36]

- “CE’METERY. n.s. . . A place where the dead are reposited. . .

- “CHURCHYARD. n.s. The ground adjoining to the church, in which the dead are buried; a cemetery. . .

- “BURYING-PLACE. n.s. A place appointed for the sepulture of dead bodies.”

- Anonymous, May 25, 1791, “Utility of planting Willow Trees in Burying Grounds” (Gazette of the United States)

- “FOR many years past, the philosophers and physicians of Europe have borne a testimony against the internment of the dead in the center of large cities. But since the discovery of the usefulness of trees in absorbing putrid air, and discharging it in a pure state, much less evil than formerly is to be apprehended from this practice. To derive and extend the utmost possible benefit from this discovery, would it not be an act of humanity in each of our religious societies, to surround their grave-yards with trees? They would afford a shade to a considerable part of our city, and would add to its coolness and ornament in the summer. The weeping willow would accord most with the place.”

- Parmentier, André, 1828, The New American Gardener (quoted in Fessenden 1828: 187)[37]

- “As to tombs and cemeteries, I should wish to banish them entirely from gardens. They always awaken melancholy reflections in old people, for they remind them of their approaching end; and a regard for their feelings should, I think, exclude from their places of resort every object which could have such an effect.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849; repr. 1991: 237)[38]

- “To these offices of pensive melancholy, it [the Weeping willow] appears to be dedicated in almost all countries. The Chinese and other Asiatic nations, and the Turks, as well as the enlightened Europeans, universally plant it in their cemeteries and last places of repose.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, December 1851, “The State and Prosperity of Horticulture” (Horticulturist 6: 540)[39]

- “A peculiar feature of what may be called the scenery of ornamental grounds in this country, at the present moment is, as we have before remarked, to be found in our rural cemeteries. They vary in size from a few, to three or four hundred acres, and in character from pretty shrubberies and pleasure grounds, to wild sylvan groves, or superb parks and pleasure grounds—laid out and kept in the highest style of the art of landscape gardening.”

Images

Inscribed

Associated

Thomas Chambers, Mount Auburn Cemetery, mid-19th century.

Attributed

Notes

- ↑ For a discussion about early American cemeteries and burial grounds, including both church and family plots, see John R. Stilgoe, Common Landscape of America, 1580 to 1845 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1982), 219–31. Stilgoe associates family plot–type burial grounds in the 17th and 18th centuries with southern culture. He argues that “Tidewater settlers confronted death and burial . . . in a manner different from New Englanders,” and points to, for example, the southern practice of maintaining plots and gravestones in contrast to Puritan neglect that was more common in the north (229), view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Charles Sloane provides a useful chart of the characteristics of American cemeteries, including date, design, location, grave marker style and material, type of manager of the cemetery, distinctive features, paradigms, and examples. See David Charles Sloane, The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), 4–5, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sloane 1991.

- ↑ Blanche Linden-Ward and David C. Sloane, “Spring Grove: The Founding of Cincinnati’s Rural Cemetery, 1845–1855,” Queen City Heritage 43 (Spring 1985): 18, view on Zotero. Note that most of the evidence collected for this project concentrates upon Protestant burial areas. This bias appears to be inherent in primary cemetery/burying ground/burial ground accounts of the American landscape. Future research needs to be conducted with regard to the burial practices between 1492 and 1850 of other faiths, especially Catholicism and Judaism, in America.

- ↑ The evidence collected here does not support David Sloane’s argument, in his otherwise illuminating study, that the term “cemetery” became the standard in the early 19th century. Sloan writes, “Although used sporadically by Europeans for centuries, the term became the standard one for a burial place in the 19th century. Rural cemeteries were different than previous burial places, and their founders believed that they deserved a distinct name.” Sloane 1991, 55, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For more about Romantic literature and its effect upon the rural cemetery movement, see David Schulyer’s chapter about rural cemeteries in his book The New Urban Landscape: The Redefinition of City Form in Nineteenth-Century America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), view on Zotero.

- ↑ For more about the history of Mount Auburn Cemetery, see Blanche Linden-Ward, Silent City on a Hill: Landscapes of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1989), view on Zotero, and Barbara Rotundo, “Mount Auburn: Fortunate Coincidences and an Ideal Solution,” Journal of Garden History 4 (July–September 1984): 223–56.

- ↑ For further information about the development of Père Lachaise, see Richard A. Etlin, The Architecture of Death: The Transformation of the Cemetery in Eighteenth-Century Paris (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1984), 299–301, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Mount Auburn Cemetery also marked a new period in the financing of cemeteries. Instead of being treated as the property of the city or a church, Mount Auburn Cemetery was run by a corporation of private, civic-minded individuals and lots were sold to the public.

- ↑ For further details about the history of Spring Grove Cemetery, see Linden-Ward and Sloane, “Spring Grove,” 17–32, view on Zotero. For more about Laurel Hill, see Keith N. Morgan, “The Emergence of the American Landscape Professional: John Notman and the Design of Rural Cemeteries,” Journal of Garden History 4 (July–September 1984): 269–90, view on Zotero. Also, see Donald Simon, “Green-Wood Cemetery and the American Park Movement,” in Essays in the History of New York City: A Memorial to Sidney Pomerantz, ed. Irwin Yellowitz (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat, 1978), 61–77, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Curl, A Celebration of Death: An Introduction to Some of the Buildings, Monuments, and Settings of Funerary Architecture in the Western European Tradition (London: Constable, 1980), 274, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. by Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Timothy Dwight, Travels in New England and New York, 4 vols (New Haven, CT: Timothy Dwight, 1821), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Isaac Weld, Travels through the States of North America and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, during the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797 (London: John Stockdale, 1799), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels in New England and New York, ed. Barbara Miller Solomon, 4 vols. (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1969), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 John Lambert, Travels through Canada, and the United States of North America in the Years 1806, 1807, and 1808, 2 vols. (London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Green Fessenden, “National Burying Ground,” New England Farmer 1, no. 26 (January 25, 1823): 206, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Douglas, My Bondage and My Freedom, ed. William L. Andrews (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Neglected Grave Yards,” New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal 7, no. 39 (April 17, 1829): 307, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Story, An Address Delivered on the Dedication of the Cemetery at Mount Auburn (Boston: Joseph T. and Edwin Buckingham, 1831), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thaddeus William Harris, A Discourse Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on the Celebration of Its Fourth Anniversary, October 3, 1832 (Cambridge, MA: E. W. Metcalf, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Harriet Martineau, Retrospect of Western Travel, 2 vols. (London: Saunders and Otley, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. B., “Horticulture in Maine,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 2 (October 1, 1836): 380–86, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Adams, The Boston Common, or Rural Walks in Cities (Boston: George W. Light, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, The Picturesque Pocket Companion and Visitor’s Guide through Mount Auburn (Boston: Otis, Broader, 1839), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nathaniel Parker Willis, American Scenery; Or, Land, Lake and River Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature (London: G. Virtue, 1840), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 James Silk Buckingham, America, Historical, Statistic, and Descriptive, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Adams, Boston Common (Boston: William D. Ticknor and H. B. Williams, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ W., “An Account of the Lowell Cemetery, Its Situation, Historical Associations, and Particular Description,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 8, no. 2 (February 1842): 47–50, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Graham Clarke, ed., The American Landscape: Literary Sources and Documents, 3 vols. (East Sussex, England: Helm Information, 1993), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Charles B. Trego, A Geography of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Edward C. Biddle, 1843), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Louisa C. Tuthill, History of Architecture, from the Earliest Times; Its Present Condition in Europe and the United States; with a Biography of Eminent Architects, and a Glossary of Architectural Terms, by Mrs. L. C. Tuthill (1848; repr. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, “Public Cemeteries and Public Gardens,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 4, no. 1 (July 1849): 9–12, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed., corrected and improved (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Fessenden, ed., The New American Gardener, 1st ed. (Boston: J. B. Russell, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, “The State and Prospects of Horticulture,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 12 (December 1851): 537–41, view on Zotero.