Difference between revisions of "Fall/Falling garden"

(→Texts) |

|||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

Citations suggest that treatise writers, with the exception of Thomas Whately (1770), usually used the term “[[slope]]” rather than “fall” in general discussions of rising and falling ground. By contrast, the term “fall” was used more specifically to describe the descents between level areas of a [[terrace]]d garden. For example, George Washington used “[[slope]]” and “fall” interchangeably to describe the same feature in his kitchen garden, but “fall” was used to describe the short descent between a series of [[terrace]]s that formed a falling garden. | Citations suggest that treatise writers, with the exception of Thomas Whately (1770), usually used the term “[[slope]]” rather than “fall” in general discussions of rising and falling ground. By contrast, the term “fall” was used more specifically to describe the descents between level areas of a [[terrace]]d garden. For example, George Washington used “[[slope]]” and “fall” interchangeably to describe the same feature in his kitchen garden, but “fall” was used to describe the short descent between a series of [[terrace]]s that formed a falling garden. | ||

| − | The concentration of falling gardens in the Chesapeake watershed area may have been due, in part, to their appropriateness to the estuarial topography in the region. Houses commonly were sited upon more protected, elevated knolls, or along the banks of many rivers and streams that fed the Chesapeake (see [[Eminence]], [[Prospect]], and [[View]]). Terracing these natural hillsides not only created level ground for planting [[bed]]s or [[parterre]]s but also enhanced [[view]]s to and from the house. For instance, when looking out from the top of the garden, each [[terrace]] below was not fully visible because of the drop in elevation. The effect was a foreshortened [[view]], often creating the impression, as Mary M. Ambler noted in 1770, that the garden at Mount Clare incorporated the broader landscape. By varying the widths of the [[terrace]]s, garden designers created the illusion of a greater or lesser distance than what actually existed. For instance, by making the [[terrace]]s near the house wider, as at the garden of William Paca in Annapolis, Md., the [[view]] from the top [[terrace]] to the summerhouse appeared more distant than it was, thus elongating the limited space of its urban lot. Research has highlighted the geometrically complex work of anonymous falling garden designers who often based the dimensions of [[terrace]]s and [[slope]]s on measurements of the dwelling house. <ref>Barbara Paca-Steele, with St. Clair Wright, “The Mathematics of an Eighteenth-Century Wilderness Garden,” ''Journal of Garden History'' 6 (October–December 1986): 299–320, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/BXR4J256]; Mark P. Leone and Paul A. Shackel, “Plane and Solid Geometry in Colonial Gardens in Annapolis, Maryland,” in ''Earth Patterns: Archaeology of Early American and Ancient Landscapes'', ed. William Kelso and Rachel M. Most (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1990), 153–67, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/W7VHDPT7 view on Zotero].</ref> | + | The concentration of falling gardens in the Chesapeake watershed area may have been due, in part, to their appropriateness to the estuarial topography in the region. Houses commonly were sited upon more protected, elevated knolls, or along the banks of many rivers and streams that fed the Chesapeake (see [[Eminence]], [[Prospect]], and [[View]]). Terracing these natural hillsides not only created level ground for planting [[bed]]s or [[parterre]]s but also enhanced [[view]]s to and from the house. For instance, when looking out from the top of the garden, each [[terrace]] below was not fully visible because of the drop in elevation. The effect was a foreshortened [[view]], often creating the impression, as Mary M. Ambler noted in 1770, that the garden at Mount Clare incorporated the broader landscape. By varying the widths of the [[terrace]]s, garden designers created the illusion of a greater or lesser distance than what actually existed. For instance, by making the [[terrace]]s near the house wider, as at the garden of William Paca in Annapolis, Md., the [[view]] from the top [[terrace]] to the [[summerhouse]] appeared more distant than it was, thus elongating the limited space of its urban lot. Research has highlighted the geometrically complex work of anonymous falling garden designers who often based the dimensions of [[terrace]]s and [[slope]]s on measurements of the dwelling house. <ref>Barbara Paca-Steele, with St. Clair Wright, “The Mathematics of an Eighteenth-Century Wilderness Garden,” ''Journal of Garden History'' 6 (October–December 1986): 299–320, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/BXR4J256]; Mark P. Leone and Paul A. Shackel, “Plane and Solid Geometry in Colonial Gardens in Annapolis, Maryland,” in ''Earth Patterns: Archaeology of Early American and Ancient Landscapes'', ed. William Kelso and Rachel M. Most (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1990), 153–67, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/W7VHDPT7 view on Zotero].</ref> |

[[File:0505.jpg|thumb|Fig. 5, Anonymous (artist), Benjamin Tanner (engraver), ''University of Virginia'', 1826.]] | [[File:0505.jpg|thumb|Fig. 5, Anonymous (artist), Benjamin Tanner (engraver), ''University of Virginia'', 1826.]] | ||

| − | Recent scholarship about the Chesapeake landscape argues that the series of [[terrace]]s connected by grass ramps or stairs (much like the series of rooms and halls in a dwelling), created a sequence of social barriers through which one navigated, with the final destination determined by one’s social status. <ref>Dell Upton, “White and Black Landscapes in Eighteenth-Century Virginia,” in ''Material Culture in America, 1600–1860'', ed. Robert Blair St. George (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1988), 357–69, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/N9BT889P view on Zotero]; Elizabeth Kryder-Reid, “The Archaeology of Vision in Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake Gardens,” ''Journal of Garden History'' 14 (spring 1994): 42–54, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IJX4M93V view on Zotero.].</ref> Without using the term “falling garden,” John Adams, succinctly described in 1777 the effect of the impressive sequence of plateaus as he walked through the “splendid | + | Recent scholarship about the Chesapeake landscape argues that the series of [[terrace]]s connected by grass ramps or stairs (much like the series of rooms and halls in a dwelling), created a sequence of social barriers through which one navigated, with the final destination determined by one’s social status. <ref>Dell Upton, “White and Black Landscapes in Eighteenth-Century Virginia,” in ''Material Culture in America, 1600–1860'', ed. Robert Blair St. George (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1988), 357–69, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/N9BT889P view on Zotero]; Elizabeth Kryder-Reid, “The Archaeology of Vision in Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake Gardens,” ''Journal of Garden History'' 14 (spring 1994): 42–54, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IJX4M93V view on Zotero.].</ref> Without using the term “falling garden,” John Adams, succinctly described in 1777 the effect of the impressive sequence of plateaus as he walked through the “splendid [[seat]]” of a barrister, Mr. Carroll, at Mount Clare: “It is a large and elegant house; it stands fronting looking down the river into the harbor; it is one mile from the water; there is a descent not far from the house;— you have a fine garden; then you descend a few steps and have another fine garden; you go down a few more and have another.” <ref>Charles Francis Adams, ed., ''The Works of John Adams'' (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1850), 435, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/WT73AURT view on Zotero].</ref> |

In addition to their popularity among planter gentry, falls or [[slope]]s were also incorporated in campus landscape designs, as in the plan of Union College in Schenectady, N.Y., by Joseph Jacques Ramée, and of the University of Virginia, designed by [[Thomas Jefferson]] [Fig. 5]. In these settings, the declivity created a separation of space, as in the formation of the series of forecourts in the Ramée plan, without imposing visual barriers. In the case of Union College, the visual effect was enhanced by its “telescopic shape, with spaces that progressively narrowed as they mounted the hill, heightening the sense of perspective depth.” <ref>Paul V. Turner, ''Joseph Ramée: International Architect of the Revolutionary Era'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 201, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/667JZS6S view on Zotero].</ref> | In addition to their popularity among planter gentry, falls or [[slope]]s were also incorporated in campus landscape designs, as in the plan of Union College in Schenectady, N.Y., by Joseph Jacques Ramée, and of the University of Virginia, designed by [[Thomas Jefferson]] [Fig. 5]. In these settings, the declivity created a separation of space, as in the formation of the series of forecourts in the Ramée plan, without imposing visual barriers. In the case of Union College, the visual effect was enhanced by its “telescopic shape, with spaces that progressively narrowed as they mounted the hill, heightening the sense of perspective depth.” <ref>Paul V. Turner, ''Joseph Ramée: International Architect of the Revolutionary Era'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 201, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/667JZS6S view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

Revision as of 13:50, June 8, 2017

(Fall garden)

See also: Terrace

History

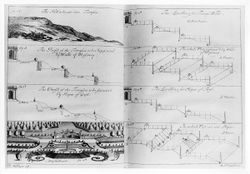

In 1789 Thomas Sheridan defined a fall as a “declivity” or “steep descent.” In American gardens, these inclines were commonly either slopes (located between terraces) or flats, as at Mount Clare in Baltimore. A garden composed of a series of falls and terraces was often called a falling garden. Level areas were generally connected by ramps or, more rarely, by stairs [Fig. 1]. In order to prevent erosion, steep falls had to be carefully constructed and either covered with turf or reinforced with masonry. The turfed fall seems to have been the predominant means of constructing a falling garden in America. Even so, evidence exists of gardens that had a single retaining wall between two levels, such as those at Riversdale in Maryland [Fig. 2], and examples of far more elaborate falling gardens with retaining walls were illustrated by Michael van der Gucht [Fig. 3]. As a reference to a descent of water, “fall” is discussed in this study as a specialized water feature (see Cascade).

The geographic distribution of falls appears to have been relatively localized, and the use of the term fairly short-lived. Citations that include the term “fall” or “falling garden” generally come from usage in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in the mid-Atlantic/Chesapeake region. Examples range from Nazareth, Pa., to the north, to Williamsburg, Va., to the south. Extant sites, such as Middleton Place, near Charleston [Fig. 4], suggest the falling garden’s wider geographic distribution. Yet, when utilized in written accounts, the term appears to have had more limited usage. The related term “slope” appears to have been used more broadly, with examples ranging from New England to Georgia and was applied to longer, gradual descents, including natural hillsides, the sides of mounds, and raised terrace walks (see Terrace). [1]

Citations suggest that treatise writers, with the exception of Thomas Whately (1770), usually used the term “slope” rather than “fall” in general discussions of rising and falling ground. By contrast, the term “fall” was used more specifically to describe the descents between level areas of a terraced garden. For example, George Washington used “slope” and “fall” interchangeably to describe the same feature in his kitchen garden, but “fall” was used to describe the short descent between a series of terraces that formed a falling garden.

The concentration of falling gardens in the Chesapeake watershed area may have been due, in part, to their appropriateness to the estuarial topography in the region. Houses commonly were sited upon more protected, elevated knolls, or along the banks of many rivers and streams that fed the Chesapeake (see Eminence, Prospect, and View). Terracing these natural hillsides not only created level ground for planting beds or parterres but also enhanced views to and from the house. For instance, when looking out from the top of the garden, each terrace below was not fully visible because of the drop in elevation. The effect was a foreshortened view, often creating the impression, as Mary M. Ambler noted in 1770, that the garden at Mount Clare incorporated the broader landscape. By varying the widths of the terraces, garden designers created the illusion of a greater or lesser distance than what actually existed. For instance, by making the terraces near the house wider, as at the garden of William Paca in Annapolis, Md., the view from the top terrace to the summerhouse appeared more distant than it was, thus elongating the limited space of its urban lot. Research has highlighted the geometrically complex work of anonymous falling garden designers who often based the dimensions of terraces and slopes on measurements of the dwelling house. [2]

Recent scholarship about the Chesapeake landscape argues that the series of terraces connected by grass ramps or stairs (much like the series of rooms and halls in a dwelling), created a sequence of social barriers through which one navigated, with the final destination determined by one’s social status. [3] Without using the term “falling garden,” John Adams, succinctly described in 1777 the effect of the impressive sequence of plateaus as he walked through the “splendid seat” of a barrister, Mr. Carroll, at Mount Clare: “It is a large and elegant house; it stands fronting looking down the river into the harbor; it is one mile from the water; there is a descent not far from the house;— you have a fine garden; then you descend a few steps and have another fine garden; you go down a few more and have another.” [4]

In addition to their popularity among planter gentry, falls or slopes were also incorporated in campus landscape designs, as in the plan of Union College in Schenectady, N.Y., by Joseph Jacques Ramée, and of the University of Virginia, designed by Thomas Jefferson [Fig. 5]. In these settings, the declivity created a separation of space, as in the formation of the series of forecourts in the Ramée plan, without imposing visual barriers. In the case of Union College, the visual effect was enhanced by its “telescopic shape, with spaces that progressively narrowed as they mounted the hill, heightening the sense of perspective depth.” [5]

-- Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Ambler, Mary M., 1770, describing Mount Clare, plantation of Charles and Margaret Tilgham Carroll, Baltimore, Md. (quoted in Sarudy 1989: 138–39) [6]

- “About two miles from Baltimore There is an exceeding handsome Seat called Mount Clare belonging to Mr. Charles Carrel of Annapolis Son of Dr. Carrel . . . took a great deal of Pleasure in looking at the bowling Green & also at the Garden which is a very large Falling Garden. . . .You step out of the Door into the Bowlg Green from which the Garden Falls & when You stand on the Top of it there is such a Uniformity of Each side as the whole Plantn seems to be laid out like a Garden.” [Fig. 6]

- Carroll, Charles (of Annapolis), 1772, in a letter to Charles Carroll (of Carrollton), describing the Carroll Garden, Annapolis, Md. (Maryland Historical Society, A. E. Carroll Papers)

- “If you wish to make a continental slope from ye Gate to ye wash house, I apprehend the Quantity of Water in great Rains going yt way may prove inconvenient. I think you should make as much of yt Road as you can with a fall to the street.”

- Anonymous, 2 May 1777, describing in the Virginia Gazette a property for sale in Fredericksburg, Va. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; hereafter CWF)

- “For sale, eight valuable lots in the town of Fredericksburg. . . . Four of those lots are well improved with a good falling garden.”

- Shippen, Thomas Lee, 1783, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd III, on the James River, Va. (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 135) [7]

- “[At Westover, there was] a view of a prettily falling grass plat . . . about 300 by 100 yards in extent an extensive prospect of James River and of all the Country and some Gentlemen’s seats on the other side.”

- Washington, George, 12 February 1785, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, Va. (Jackson and Twohig, eds., 1978: 4:89) [8]

- “Planted Eight young Pair Trees sent me by Doctr. Craik in the following places. . ..

- “3 Brown Beuries in the west square in the Second flat—viz. 1 on the border (middle thereof) next the Fall or slope—the other two on the border above the walk next the old Stone Wall.”

- Anonymous, 22 April 1794, describing in the Baltimore Daily Intelligencer the garden of John Salmon, Baltimore, Md. (quoted in Sarudy 1989: 130) [6]

- “The garden ground, which is in fine order, is laid off in beautiful falls: in it is an excellent cold bath and a milk house through which there runs a constant stream of water.”

- Ogden, John Cosens, 1800, describing a garden in Nazareth, Pa. (p. 46) [9]

- “The strait and circular walks, the windings up the hill, the falling gardens ascended by steps, the banks, summer-houses, seats, trees, herbs, fruits, vegetables and flowers are seen in great variety.

- “Most of the American forest trees and many exotic plants are here. It is an elegant garden in miniature.”

- Anonymous, 24 January 1800, describing in the Virginia Herald a property for sale in Madison County, Va. (CWF)

- “Haphazard Mills and Farm for sale. . . . The improvements on the farm are a new dwelling house . . . and an unfinished falling garden, with several springs of good water near the house.”

- Anonymous, 1805, describing in the Virginia Argus a construction project in Richmond, Va. (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 26) [7]

- “ERECTED A BATHING HOUSE At the Falling Garden, CONTAINING four rooms: each has a Bath, and supplied with Hot and Cold Water.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, 13 October 1816, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, Pa. (Miller, Hart, and Ward, eds., 1991: 3:452) [10]

- “Other parts of my farm excited the curiousity of the Public—a wind-mill for pumping Water for the Cattle &c.—A falling Garden, fountain, fish Pond, common Sewers &c Machines to add [aid] the dairy and carriages of various uses—all these things employed the whole of my time to emprove & to keep them in proper order.”

- Anonymous, 24 December 1817, describing in the Virginia Herald a property for sale in Culpeper County, Va. (CWF)

- “For sale . . . the mansion house tract. . . . The grounds well laid off about the house, with a beautiful and productive falling garden.”

- Watson, John Fanning, 1857, describing the garden of Israel Pemberton, Philadelphia, Pa. (1:375) [11]

- “The garden itself being upon an inclined plane, had three or four falls or platforms.”

Citations

- Whately, Thomas, 1770, Observations on Modern Gardening ([1770] 1982: 17, 25) [12]

- “If a steep descends in a succession of abrupt falls, nearly equal, they have the appearance of steps, and are neither pleasing nor wild; but if they are made to differ in height and length, the objection is removed: . . .

- “if a line of trees run close upon the edge of an abrupt fall, they give it depth and importance. By such means a view may be improved.”

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.) [13]

- “FALL, fa’l. s. . . . declivity, steep descent; cataract, cascade; the outlet of a current into any other water.”

Images

Inscribed

Charles Willson Peale, Lower falls of Schuylkill, 5 miles from Philadelphia, c. 1770.

George Washington, Drawing and Notes for a Ha-Ha Wall at Mount Vernon, October 1798, 1798.

Associated

Attributed

Michael van der Gucht, Illustration for chapter entitled: "Of different Terrasses and Stairs, with their most exact Proportions," in A.-J. Dézallier d’Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712), pl. opp. p. 117.

John or William Bartram, A Draught of John Bartram’s House and Garden as it appears from the River, 1758.

Francis Guy, Mt. Deposit, 1803-05.

Anthony St. John Baker (artist), B. King (lithograper), Riversdale, near Bladensburg, 1827.

Notes

- ↑ The term “slope,” like “fall,” described a declivity. In landscape design vocabulary it was used to refer to both a gradual descent and a steep grade, such as that on a mount or between terraces, as in the plan for a Garden Olitory at Jefferson’s Monticello.

- ↑ Barbara Paca-Steele, with St. Clair Wright, “The Mathematics of an Eighteenth-Century Wilderness Garden,” Journal of Garden History 6 (October–December 1986): 299–320, [1]; Mark P. Leone and Paul A. Shackel, “Plane and Solid Geometry in Colonial Gardens in Annapolis, Maryland,” in Earth Patterns: Archaeology of Early American and Ancient Landscapes, ed. William Kelso and Rachel M. Most (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1990), 153–67, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Dell Upton, “White and Black Landscapes in Eighteenth-Century Virginia,” in Material Culture in America, 1600–1860, ed. Robert Blair St. George (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1988), 357–69, view on Zotero; Elizabeth Kryder-Reid, “The Archaeology of Vision in Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake Gardens,” Journal of Garden History 14 (spring 1994): 42–54, view on Zotero..

- ↑ Charles Francis Adams, ed., The Works of John Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1850), 435, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Paul V. Turner, Joseph Ramée: International Architect of the Revolutionary Era (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 201, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Barbara Wells Sarudy, "Eighteenth-Century Gardens of the Chesapeake", Journal of Garden History, 9 (1989), 104–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, ed. by Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, 6 vols (Charlottesville, Va.: University Press of Virginia, 1978), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John C. Ogden, An Excursion into Bethlehem & Nazareth, in Pennsylvania, in the Year 1799 (Philadelphia: Charles Cist, 1800), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al, eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family: Charles Willson Peale: Artist in Revolutionary America, 1735-1791. Vol. 1; Charles Willson Peale, Artist as Museum Keeper, 1791-1810. Vol 2, Pts. 1-2; The Belfield Farm Years, 1810-1820. Vol. 3; The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale. Vol. 5. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1983–2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Fanning Watson, Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden Time; Being a Collection of Memoirs, Anecdotes, and Incidents of the City and Its Inhabitants, and of the Earliest Settlements of the Inland Part of Pennsylvania, from the Days of the Founders, 2 vols (Philadelphia: E. Thomas, 1857), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Whately, Observations on Modern Gardening, 3rd edn (London: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas A. Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews...., 5th edn (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), view on Zotero.