Difference between revisions of "Landscape gardening"

(→Usage) |

|||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

: “in the ''natural parks'' of America—the oak openings of the West—where, over a gently rolling surface of thousands of acres, you see grouped, precisely as in an English [[Park]], but sometimes on a still grander scale, the noblest trees—now singly, and now three or four, or half a dozen together,—trees, each one of which would have been chosen by CLAUDE as a study for the foreground of his wonderful landscapes—which are the master-pieces of slyvan [''sic''] beauty. Nearer home, such a growth may be seen in the [[meadow]] [[park]] at Geneseo,—the WADSWORTH estate, previously described by us—where are as fine oaks, by hundreds, as are to be found in any park in England. | : “in the ''natural parks'' of America—the oak openings of the West—where, over a gently rolling surface of thousands of acres, you see grouped, precisely as in an English [[Park]], but sometimes on a still grander scale, the noblest trees—now singly, and now three or four, or half a dozen together,—trees, each one of which would have been chosen by CLAUDE as a study for the foreground of his wonderful landscapes—which are the master-pieces of slyvan [''sic''] beauty. Nearer home, such a growth may be seen in the [[meadow]] [[park]] at Geneseo,—the WADSWORTH estate, previously described by us—where are as fine oaks, by hundreds, as are to be found in any park in England. | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:0947.jpg|thumb|Fig. 10, Anonymous, "Study of Trees in Park Scenery" Geneseo, in [[A. J. Downing]], ed., ''Horticulturist'' 6, no. 9 (September 1, 1851), pl. opp. p. 394. ]] |

: “It is remarkable, that these grand [[park]]s of American, and the best specimens of English taste in '''Landscape Gardening''', should be such close counterparts of one another. And though a man may have room to plant only a half a dozen trees, yet he should study such examples as a sculptor would study the APOLLO or the VENUS—to make himself familiar with that high-water level of the beautiful in form, where both art and nature meet and become identical.” [Fig. 10] | : “It is remarkable, that these grand [[park]]s of American, and the best specimens of English taste in '''Landscape Gardening''', should be such close counterparts of one another. And though a man may have room to plant only a half a dozen trees, yet he should study such examples as a sculptor would study the APOLLO or the VENUS—to make himself familiar with that high-water level of the beautiful in form, where both art and nature meet and become identical.” [Fig. 10] | ||

Revision as of 20:11, February 28, 2017

History

The phrase landscape gardening referred either specifically to the irregular mode of laying out gardens that originated in England in the early eighteenth century or, more generally, to the art of designing ornamental grounds. The phrase came into currency at the same time that the theoretical basis of the art of landscape and garden design was being examined and that the modern, or natural, style was on the rise. Therefore, the style and the art were often conflated so that it was not unusual for the phrase “the modern style of landscape gardening” to be used. This modern (or natural) style was often contrasted with the “geometric or ancient style of gardening,” which was characterized by some critics as the primitive style that predated the theorization of garden design as a fine art. [1] The practice of landscape gardening in this sense resulted in the landscape garden that, according to John J. Thomas (1848), was “composed of trees, lawns, and sheets of water.” In general, it was an approach intended for extensive grounds that incorporated a park into the scheme.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe’s 1798 statement that landscape gardening is what “the art of decorating Grounds is called in England” is somewhat ambiguous. It remains unclear as to whether he meant to define landscape gardening as the English style specifically or as the concept of designing ornamental grounds generally. The second, more inclusive sense of landscape gardening was formulated by practitioners like J. C. Loudon and A. J. Downing, who promoted it as a liberal art akin to painting or music. In An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), Loudon explained that landscape gardening was a practice with a theoretical framework that had been developing since the early eighteenth century: “[T]he art of arranging the different parts which compose the external scenery of a country-residence, so as to produce the different beauties and conveniences of which that scene of domestic life is susceptible.” This included both the geometric and natural styles. Downing, in his Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), presented landscape gardening as a fine art, and as an ideal that resulted in “beautiful” and “picturesque” effects [Figs. 1 and 2].

Loudon and Downing argued that landscape gardening, whether in the geometric or modern style, was an art of imitation built on principles and not an art of facsimile, that is, the pure replication of natural scenery. Downing attributed the phrase “landscape gardening” to William Shenstone but added that it could be applied retroactively to the classical or ancient garden style. Even these theorists periodically slipped into the more exclusive usage at times, considering only the irregular modes, or rather, the modern style garden as landscape gardening (see Picturesque).

The stricter definitions of landscape gardening stipulated that this fine art depended solely on the “modern,” or natural style. George Watterston, for example, in 1844 wrote pointedly, “Landscape Gardening, is a modern art. Previous to the last century, it may be said scarcely to have existed.” John J. Thomas (1848) contrasted the larger landscape garden made up of trees, lawns, and sheets of water with the style of the flower garden laid out in geometrical lines. A specific meaning of landscape gardening as a particular style and not a more general discipline was clear in several citations where an author wrote “landscape or picturesque gardening.” That “landscape garden” as a garden type and “landscape gardening” as the professional practice that produced it were being used synonymously is clear.

Thomas Jefferson was intrigued both theoretically and experimentally by the landscape gardening movement. In this period Thomas Whately’s Observations on Modern Gardening (1770) was considered the most mature writing about landscape gardening, and it was with this book in hand that Jefferson toured English gardens with John Adams in 1786. Whately’s comments on color, meaning, association, and function in the landscape garden are reflected in Jefferson’s notes made during the latter’s visits to several of the most famous English gardens. A comparison of these notes to his instructions for Monticello gives evidence of the profound impact of that trip on his sense of landscape aesthetics. Jefferson was particularly interested in flowers and shrubs that brought a great deal of color and variety to his garden. Although he used the phrase “the art of gardening” or simply “gardening” when discussing the subject, Jefferson was clearly considering the recent version of the art form “in the perfection to which it [had] been lately brought in England.” Jefferson also referred to landscape gardening as “the style of the English garden.” [2]

The broader meanings of the phrase “landscape gardening” as a fine art continued to be used into the nineteenth century. Edgar Allen Poe described two types of landscape gardening, the natural and the artificial in his short story, “The Landscape Garden” (1842). For William H. Ranlett (1849), landscape gardening was formerly practiced in the ancient or geometric style but succeeded in recent times by the modern or natural style.

-- Therese O'Malley

Texts

Usage

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, 1798–99, “An Essay on Landscape” (1977: 469–70) [3]

- “Mr. Knight in his elegant, but illnatured poem, on Landscape gardening (as the art of decorating Grounds is called in England) has lines, which have the following sentiment, although I am uncertain about Versification:

- ‘Search, as you will, the whole creation round

- ’Tis after all but Water, Trees, and Ground:

- Vary your spot,—seek something new to please;

- What see you? Water,—ground,—and trees!’”

- Birch, William Russell, n.d. [c. 1800], describing his garden at Springland, estate of William Russell Birch, near Bristol, Pa. (quoted in Cooperman 1999: 170–71) [4]

- “Some directions for its improvement as a lesson on Landscape gardening . . . invite the warbling songsters to your shades, let nature be your god, she has charms with all her faults that art can never give, with cautious steps and anxious care preserve her sweets, mark you [a] rich spot of sandy soil, from which dranes moisture all the year alike, wet or dry, its watery beds are one, flat lays its surface, high and secure its station, on the bank, there chuse your botany to place, with ornaments of taste. . . .

- “Trim not your bows away with wanton hand, let cautious tgaste reserve them for effect, spoil not your broken ground with too haste leveling, study well what new charms by addition may be made, so parly with your fancy till you find it’s in your way, sport well your conceptions, seek not to undo what nature well intends, advantage take from the roughest rudeness chance has given, so let the refinement of your taste work its way; thus with wholesome caution was this place improved, track to verigate the seens laid out for walks, shrubs to hid what suted not with taste were placed, beds for flowers, where most were wished, nor was lawn neglected whereare the space allow’d[;] the ponds with fish were stock’d[,] a green Lodge for shelter was prepared[,] till the labours of delight were done.” [Fig. 3]

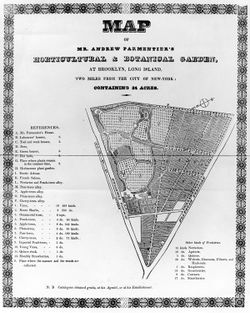

- S., J. W., September 1829, describing André Parmentier’s horticultural and botanical garden, Brooklyn, N.Y. (Gardeners’ Magazine 8: 72)

- “In short, this establishment is well worthy of notice as one of the few examples in the neighbourhood of New York, of the art of laying out a garden so as to combine the principles of landscape-gardening with the conveniences of the nursery or orchard.” [Fig. 4]

- Dearborn, H.A.S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Mass. (quoted in Harris 1832: 64–65) [5]

- “it is proposed, that a tract of land called ‘Sweet Auburn,’ situated in Cambridge, should be purchased. As a large portion of the ground is now covered with trees, shrubs, and wild flowering plants, avenues and walks may be made through them, in such a manner as to render the whole establishment interesting and beautiful, at a small expense, and within a few years; and ultimately offer an example of landscape or picturesque gardening, in conformity to the modern style of laying out grounds, which will be highly creditable to the Society.”

- MacDonald, James, October 1839, describing the Bloomingdale Asylum for the Insane, New York, N.Y. (quoted in Hawkins 1991: 86) [6]

- “The approach to the Asylum from the southern entrance, by the stranger who associates the most sombre scenes with a lunatic hospital, is highly pleasing. The sudden opening of the view, the extent of the grounds, the various avenues gracefully winding through so large a lawn; the cedar hedges, the fir, and other ornamental trees, tastefully distributed or grouped, the variety of shrubbery and flowers; in fine, the assemblage of so many objects to please the eye, and relieve the melancholy mind from its sad musings, strike him as one of the most successful and useful instances of landscape gardening.” [Fig. 5]

- Cleaveland, Nehemiah, 1847, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Mass. (p. 14) [7]

- “Mount Auburn appears to be ‘the first example in modern times of so large a tract of ground being selected for its natural beauties, and submitted to the processes of landscape gardening, to prepare it for the reception of the dead.’” [Fig. 6]

- Downing, A. J., 1849, “Essay on Landscape Gardening” ([1849] 1991: 40–41, 44–47, 52–53) [8]

- “The only practitioner of the art [of Landscape gardening], of any note, was the late M. Parmentier of Brooklyn, Long Island. . . .

- “During M. Parmentier’s residence on Long Island, he was almost constantly applied to for plans for laying out the grounds of country seats, by persons in various parts of the Union, as well as in the immediate proximity of New York. In many cases he not only surveyed the demesne to be improved, but furnished the plants and trees necessary to carry out his designs. Several plans were prepared by him for residences of note in the Southern States; and two or three places in Upper Canada, especially near Montreal, were, we believe, laid out by his own hands and stocked from his nursery grounds. In his periodical catalogue, he arranged the hardy trees and shrubs that flourish in this latitude in classes, according to their height, etc., and published a short treatise on the superior claims of the natural, over the formal or geometric style of laying out grounds. In short, we consider M. Parmentier’s labors and examples as having effected, directly, far more for landscape gardening in America, than those of any other individual whatever. . . .

- “There is no part of the Union where the taste in Landscape Gardening is so far advanced, as on the middle portion of the Hudson. The natural scenery is of the finest character, and places but a mile or two apart often possess, from the constantly varying forms of the water, shores, and distant hills, widely different kinds of home landscape and distant view. Standing in the grounds of some of the finest of these seats, the eye beholds only the soft foreground of smooth lawn, the rich groups of trees shutting out all neighboring tracts, the lake-like expanse of water, and, closing the distance, a fine range of wooded mountain. A residence here of but a hundred acres, so fortunately are these disposed by nature, seems to appropriate the whole scenery round, and to be a thousand in extent.

- “At the present time, our handsome villa residences are becoming every day more numerous, and it would require much more space than our present limits, to enumerate all the tasteful rural country places within our knowledge, many of which have been newly laid out, or greatly improved within a few years. But we consider it so important and instructive to the novice in the art of Landscape Gardening to examine, personally, country seats of a highly tasteful character, that we shall venture to refer the reader to a few of those which have now a reputation among us as elegant country residences.

- “Hyde Park, on the Hudson . . . has been justly celebrated as one of the finest specimens of the modern style of Landscape Gardening in America. Nature has, indeed, done much for this place, as the grounds are finely varied, beautifully watered by a lively stream, and the views are inexpressibly striking from the neighborhood of the house itself, including, as they do, the noble Hudson for sixty miles in its course, through rich valleys and bold mountains. . . . But the efforts of art are not unworthy so rare a locality; and while the native woods, and beautifully undulating surface, are preserved in their original state, the pleasure-grounds, roads, walks, drives, and new plantations, have been laid out in such a judicious manner as to heighten the charm of nature. . . . plans for laying out the grounds were furnished by Parmentier.” [Fig. 7]

- “Blithewood, the seat of R. Donaldson, Esq., near Barrytown on the Hudson, is one of the most charming villa residences in the Union. The natural scenery here, is nowhere surpassed in its enchanting union of softness and dignity—the river being four miles wide, its placid bosom broken only by islands and gleaming sails, and the horizon grandly closing in with the tall blue summits of the distant Kaatskills. The smiling, gently varied lawn is studded with groups and masses of fine forest and ornamental trees, beneath which are walks leading in easy curves to rustic seats, and summer houses placed in secluded spots, or to openings affording most lovely prospects. (See frontispiece.) In various situations near the house and upon the lawn, sculptured vases of Maltese stone are also disposed in such a manner as to give a refined and classic air to the grounds. [Fig. 8]

- “The seat of the Wadsworth family, at Geneseo, is the finest in the interior of the state of New York. Nothing, indeed, can well be more magnificent than the meadow park at Geneseo. It is more than a thousand acres in extent, lying on each side of the Genesee river, and is filled with thousands of the noblest oaks and elms, many of which, but more especially the oaks, are such trees as we see in the pictures of Claude, or our own Durand; richly developed, their trunks and branches grand and majestic, their heads full of breadth and grandeur of outline. . . . ” [Fig. 9]

- “These oaks, distributed over a nearly level surface, with the trees disposed either singly or in the finest groups, as if most tastefully planted centuries ago, are solely the work of nature; and yet so entirely is the whole like the grandest planted park, that it is difficult to believe that all is not the work of some master of art, and intended for the accomplishment of a magnificent residence. Some of the trees are five or six hundred years old.”

- Downing, A. J., 1 September 1851, “Study of Park Trees” (Horticulturist 6: 427)

- “in the natural parks of America—the oak openings of the West—where, over a gently rolling surface of thousands of acres, you see grouped, precisely as in an English Park, but sometimes on a still grander scale, the noblest trees—now singly, and now three or four, or half a dozen together,—trees, each one of which would have been chosen by CLAUDE as a study for the foreground of his wonderful landscapes—which are the master-pieces of slyvan [sic] beauty. Nearer home, such a growth may be seen in the meadow park at Geneseo,—the WADSWORTH estate, previously described by us—where are as fine oaks, by hundreds, as are to be found in any park in England.

- “It is remarkable, that these grand parks of American, and the best specimens of English taste in Landscape Gardening, should be such close counterparts of one another. And though a man may have room to plant only a half a dozen trees, yet he should study such examples as a sculptor would study the APOLLO or the VENUS—to make himself familiar with that high-water level of the beautiful in form, where both art and nature meet and become identical.” [Fig. 10]

- Downing, A. J., December 1851, “State and Prosperity of Horticulture” (Horticulturist 6: 540–41) [9]

- “The plan [for a public ground in Washington] embraces four or five miles of carriage-drive—walks for pedestrians—ponds of water, fountains and statues—picturesque groupings of trees and shrubs, and a complete collection of all the trees that belong to North America. It will, if carried out as it has been undertaken, undoubtedly give a great impetus to the popular taste in landscape-gardening and the culture of ornamental trees; and as the climate of Washington is one peculiarly adapted to this purpose—this national park may be made a sylvan museum such as it would be difficult to equal in beauty and variety in any part of the world.”

Citations

- Whately, Thomas, 1770, Observations on Modern Gardening (1982: 1–2) [10]

- “Gardening, in the perfection to which it has been lately brought in England, is entitled to a place of considerable rank among the liberal arts. It is as superior to landskip painting, as a reality to a representation: it is an exertion of fancy, as subject for taste; and being released now from the restraint of regularity, and enlarged beyond the purposes of domestic convenience, the most beautiful, the most simple, the most noble scenes of nature are all within its province: for it is no longer confined to the spots from which it borrows its name, but regulates also the disposition and embellishments of a park, a farm, or a riding; the business of a gardener is to select and to apply whatever is great, elegant, or characteristic in any of them; to discover and to show all the advantages of the place upon which he is employed; to supply its defects, to correct its faults, and to improve the beauties.

- “Nature, always simple, employs but four materials in the composition of her scenes, ground, wood, water, and rocks. The cultivation of nature had introduced a fifth species, the buildings requisite for the accommodation of men. Each of these again admit of varieties in their figure, dimensions, color, and situation. Every landskip is composed of these parts only; every beauty in a landskip depends on the applications of their several varieties.”

- Gregory, G., 1816, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (2:n.p.) [11]

- “GARDENING. This art, so natural to man, so improving to health, so conducive to the comforts and the best luxuries of life, may properly be divided into two branches; practical, and picturesque or landscape gardening.

- “The former is what every person, except the inhabitants of populous cities, has more or less occassion to practise; the latter is a privilege which only the very opulent can enjoy, and which must consequently be the elegant amusement of a chosen few.

- “Picturesque or landscape gardening should certainly never be attempted on a small scale. Indeed we are not certain that we may not be incurring a solecism in applying the term gardening to this department of agriculture. It is properly the art of laying out grounds; and the park or the farm, not the garden, is its object. It never can be attempted with success on a smaller scale than 20 acres; but 50 or 100, or even more, are better adapted to the design. . . .

- “Landscape or picturesque gardening, is so much the work of fancy, and so much depends upon the situation, or what the celebrated Mr. Brown used to call the capability of the place, that no precise rules can be laid down concerning it. All, therefore, that can be expected, is a few lose [sic] hints, on which the man of taste may improve according to circumstances.”

- Hosack, David, 1824, An Inaugural Discourse, Delivered Before the New-York Horticultural Society (pp. 10, 12–13, 24–25) [12]

- “Horticulture embraces three objects. 1st. The cultivation of the plants of the table, including culinary vegetables and fruits. 2d. Those plants which are considered as ornamental. And 3d. Landscape gardening; or, the art of laying out grounds in such manner as may render them most conducive to utility and beauty. . . .

- “I pass on to remark, that very little has been effected in the science of gardening, until the last fifty years. Within that period, a number of individuals, distinguished for their taste and education, have given their attention to the study of this interesting subject, and especially in France and in Great Britain, have produced important changes in every department of horticulture, including that branch of it more especially, denominated landscape gardening. In this list, the names of Miller, Marshall, Abercrombie, Brown, Nicol, Repton, Knight, and Loudon,* as well as others, whose taste and opportunities led them to the cultivation of this art, hold a distinguished place. . . .

- “8th. Another advantage which such an establishment should possess, is that of exemplifying the principles of Ornamental Planting, or Landscape Gardening. The ground should be selected of such form and variety as will admit of such decoration. And in the cultivation of the various plants of the collection, their distribution may ever be rendered subservient to this great object, and thereby become the means of spreading extensively among our citizens a taste for one of the highest recreations that the human heart can receive, and one which will go far in the improvement of the moral principle, and in diverting the mind from pursuits of a less worthy nature; for the mind that is not actively engaged in virtuous pursuits will most probably be occupied with those of a contrary character.

- “* Observations on Modern Gardening.”

- Loudon, J. C., 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 994–96) [13]

- “7156. In landscape gardening, the art of the gardener is directed to different objects, and some of them of a higher kind than any belonging to gardening as an art of culture. In the three branches [of gardening] hitherto considered, art is chiefly employed in the cultivation of plants, with a view of obtaining their products; but in the branch now under consideration, art is exercised in disposing of ground, buildings, and water, as well as the vegetating materials which enter into the composition of verdant landscape. This is, in a strict sense, what is called landscape-gardening, or the art of creating or improving landscapes; but as landscapes are seldom required to be created for their own sakes, landscape-gardening, as actually practised, may be defined, ‘the art of arranging the different parts which compose the external scenery of a country-residence, so as to produce the different beauties and conveniences of which that scene of domestic life is susceptible.’ . . .

- “7161. With respect to the modern style . . . there appear to be two principles which enter into its composition; those which regard it as a mixed art, or an art of design, and which are called the principles of relative beauty; and those which regard it as an imitative art, and are called the principles of natural or universal beauty. The ancient or geometric gardening is guided wholly by the former principles; landscape-gardening, as an imitative art, wholly by the latter; but as the art of forming a country-residence, its arrangements are influenced by both principles. In conformity with these ideas, and with our plan of treating both styles, we shall first consider its principles as an inventive or mixed, and secondly as an imitative art.”

- Dearborn, H.A.S., 19 September 1829, An Address, Delivered Before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (1833: 16) [14]

- “The natural divisions of Horticulture are the Kitchen Garden, Seminary, Nursery, Fruit Trees and Vines, Flowers and Green Houses, the Botanical and Medical Garden, and Landscape, or Picturesque Gardening.”

- Loudon, J. C., 1832, Review of W. Gilpin, Esq., “Practical Hints on Landscape Gardening” (Gardeners’ Magazine 8: 701–2) [15]

- “Landscape-gardening, it will be allowed is, to a certain extent, an art of imitation. Now, an imitative art is not one which produces fac similes of the things to be imitated; but one which produces imitations, or resemblances, according to the manner of that art. Thus, sculpture does not attempt colour, not painting to raise surfaces in relief; and neither attempt to deceive. In the like manner, the imitator, in a park or pleasure-ground, of a landscape composed of ground, wood, and water, does not produce fac similes of the ground, wood, and water, which he sees around him on every side; but of ground, wood and water, arranged in imitation of nature, according to the principles of his particular art. The character of this art has varied from the earliest times to the present day; but, profoundly examined, the principle which guided the artist remains the same; and the successive fashions that have prevailed will be found to confirm our view of the subject, viz., that all imitations of nature worthy of being characterised as belonging to the fine arts are not fac-simile imitations, but imitations of manner. To apply this principle to the planting of trees in park or pleasure-ground scenery; nature, in any given locality, makes use of a certain number of trees found indigenous there; but the garden imitator of natural woods introduces either other forms and dispositions of the same kinds of trees, as in the geometric style; or the same dispositions of other species of trees, as in the most improved practice of the modern style. In neither case does the artist produce a correct fac simile of nature; for, if he did, however beautiful the scene copied, the beauty produced would be merely that of repetition. But we have neither room nor time at present fully to illustrate this theory. Let it suffice for us to state, for the consideration of those of our readers who have reflected on the subject, that there is as certainly, in gardening, as an art of imitation, the gardenesque, as there is, in painting and sculpture, the picturesque and sculpturesque.”

- Loudon, J. C., 1834, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 1163–64, 1167–68) [16]

- “BOOK IV. LANDSCAPE-GARDENING....

- “CHAP. I. Principles of Landscape-Gardening.

- “6691. The principles of landscape-gardening, like those of every other art, are founded on the end in view. ‘Gardens and buildings,’ Lord Kaimes observes, ‘may be destined solely for use, or solely for beauty or for both. Such variety of destination bestows upon these arts a great command of beauties, complex not less than various. Hence the difficulty of forming an accurate taste in gardening and architecture; and hence, the difference or wavering of taste in these arts, is greater than in any art that has but a single destination.’ (Elements of Criticism, 4th edit. vol. ii. p. 431) Not to consider landscape-gardening with a view to these different beauties, but to treat it merely as ‘the art of creating landscape,’ would embrace only a small part of the art of laying out grounds, and leave incomplete a subject which contributes to the immediate comfort and happiness of a great body of the enlightened and opulent in this and in every country;—an art, as the poet Mason observes,

- “_____ ‘which teaches wealth and pride

- “‘How to obtain their wish—the world’s applause.’

- “6693. . . . The ancient or geometric gardening is guided wholly by the former principles; and landscape-gardening, as an imitative art, wholly by the latter; but when landscape-gardening is considered as the art of forming a country residence, its arrangements are influenced by both principles. In conformity with these ideas, and with our plan of treating of both styles, we shall first consider its principles as an inventive or mixed, and secondly as an imitative art. . . .

- “Sec. II. Beauties of Landscape-Gardening, considered as an imitative Art, and Principles of their Production.

- “6708. The chief object of all the imitative arts is the production of natural or universal beauty. Music, poetry, and painting, are the principal imitative arts; to these has been lately added landscape-gardening, an art which has for its object the production of landscape by combinations of the actual materials of nature, as landscape-painting has for its object their imitation by combinations of colours. Landscape-gardening has been said ‘to realize whatever the fancy of the painter has imagined’ (Girardin); and, ‘to create a scenery more pure, more harmonious, and more expressive, than any that is to be found in nature herself.’ (Alison.) . . . A more correct idea of its capacities, in our opinion, is suggested by the remark of Horace Walpole, when he represents it as ‘proud of no other art than that of softening nature’s harshness, and copying her graceful touch.’ . . .

- “6709. To what kind or degree of beauty, then, can landscape-gardening aspire? To this we answer, that, abstracted from all relations of utility and design, it can seldom succeed in producing any thing higher than picturesque beauty; what we shall call gardenesque beauty, or such a harmonious mixture of forms, colours, lights, and shades, as will be grateful to the sight of men in general; and more particularly to such as have made this beauty in some degree their study. . . .

- “6712. The principles of imitative landscape-gardening, in that view of this term which limits it to ‘the art of creating landscape of picturesque beauty,’ we consider, with Girardin, Price, Knight, and other authors, to be those of painting; and in viewing it as adding to picturesque beauty some other natural expression, as of grandeur, decay, melancholy &c., we consider it, with Pope, Warton, Gray, and Eustace, as requiring; both in the designer and observer, the aid of a poetic mind; that is, of a mind conversant with all those different emotions or pleasures of imagination, which are called up by certain signs of affecting or interesting qualities, furnished by sounds, motion, buildings, and other objects.”

- Anonymous, 1 April 1837, “Landscape Gardening” (Horticultural Register 3: 121–24, 131) [17]

- “A remarkable characteristic of the people of our nation, is a fondness for change. This is beneficial to a certain limit, as it impels to industry, to enterprise and improvement. But it is often carried to such an extent as to become a positive evil. It results in a restlessness of habit which approaches that of some of the wandering nations of Asia. We are dissatisfied with the present good. . . . And how is this to be prevented, how is this evil to be overcome? A powerful means would certainly be to induce a taste for moral improvement, and for embellishing the scenery about our homes, which would greatly contribute to the increase of our attachment to them, and to make us satisfied and contented. A love of nature, it is said, is a love of our country; not less so, then, is nature when improved by art, and applied by our own hands to increasing the attractions of our native land. . . .

- “In urging the importance of a greater attention to landscape gardening, we are far from desiring an extravagant outlay of expense. . . . Now, instead of expending so much in erecting large and showy buildings, let at least a small sum be reserved for improvements in planting trees and shrubbery. Half an acre of ground about a house, and fifty dollars appropriated to planting it, would contribute far more to its appearance, than two thousand dollars expended in additional embellishments of the house alone. . . .

- “Confining ourselves to the modern or natural style, we shall proceed to offer some remarks on its characteristics. Landscape gardens in this style generally present either picturesque, or what is termed gardenesque scenery. . . .

- “Although we have but few instances of fine landscape gardening in this country, yet an inexhaustible store of ideas may be derived from the beautiful and ever varying natural scenery which our country so richly affords.”

- Anonymous, July 1841, book review of A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (Magazine of Horticulture 7: 265–66)

- “The historical sketches are interesting, and include brief notices of the progress of landscape gardening throughout the country. The next chapter, on the Beauties of Landscape Gardening, is one of the most valuable; the hints relative to what landscape gardening consists of, are well drawn, and must be read with great profit by every individual who wishes to improve an old place, or lay out a new one. As an imitative art, its nature and principles are fully explained. With a study of this portion of Mr. Downing’s book, we are persuaded every planter will be able to effect great improvements in his grounds. Beautifying a residence does not consist in merely setting out trees, but rather in planting them in such situations as will give the greatest expression to the scene. . . .

- “In conclusion, we must not omit to remark, that Mr. Downing has given us an excellent volume, and, we might add, for a pioneer in the great art of landscape gardening, in this country, one which will be the means of placing the art at once upon a sure footing. Every country gentleman, or possessor of a cottage or villa residence, should read it, if he has the least taste or desire to embellish his grounds.”

- Poe, Edgar Allan, 1842, “The Landscape Garden” (pp. 325, 326) [18]

- “yet my friend could not fail to perceive that the creation of the Landscape-Gardner offered to the true Muse the most magnificent of opportunities. Here was, indeed, the fairest field for the display of invention, or imagination, in the endless combining of forms of novel Beauty; the elements which should enter into combination being, at all times, and by a vast superiority, the most glorious which the earth could afford. In the multiform of the tree, and in the multicolor of the flower, he recognized the most direct and the most energetic effort of Nature at physical Beauty. . . .

- “‘There are, properly,’ he writes, ‘but two styles of landscape-gardening, the natural and the artificial. One seeks to recall the original beauty of the country, by adapting its means to the surrounding scenery; cultivating trees in harmony with the hills or plain of the neighboring land; detecting and bringing into practice those nice relations of size, proportion and color which, hid from the common observer, are revealed every where to the experienced student of nature. The result of the natural style of gardening, is seen rather in the absence of all defects and incongruities—in the prevalence of a beautiful harmony and order, than in the creation of any special wonders or miracles. The artificial style has as many varieties as there are different tastes to gratify. It has a certain general relation to the various styles of building. There are the stately avenues and retirements of Versailles; Italian terraces; and a various mixed old English style, which bears some relation to the domestic Gothic or English Elizabethan architecture. Whatever may be said against the abuses of the artificial landscape-gardening, a mixture of pure art in a garden scene, adds to it a great beauty. This is partly pleasing to the eye, by the show of order and design, and partly moral. A terrace, with an old moss-covered balustrade, calls up, at once, to the eye, the fair forms that have passed there in other days. The slightest exhibition of art is an evidence of care and human interest.’”

- Watterston, George, May 1844, “Landscape Gardening” (pp. 306, 310–12) [19]

- “Landscape Gardening is a modern art. Previous to the last century, it may be said scarcely to have existed. . . .

- “Landscape Gardening is not an imitative or imaginative art. It is not a copy of nature, but nature itself. All the materials are prepared and even shaped by her, and the arrangement and disposition of them in such a manner as to render them beautiful and picturesque depend upon the skill and taste of the improver. He executes, with the materials with which nature furnishes him, the landscape he has previously formed in his mind and which he must adapt to the peculiar locality of the grounds he may be called upon to improve. . . . It is true, that Landscape Gardening is freed from one essential portion of art and which is its principal charm in painting. We mean execution, which in gardening is left to nature. But this does not lesson the skill and talent requisite for such a purpose, ‘since,’ says the writer above quoted, ‘besides the painter’s eye and sensibility, a master in Landscape Gardening must also possess a high degree of prescient vision, so as to be able to foresee results that will not develope and manifest themselves till long afterwards.’ . . .

- “In a painting, the eye is confined to a single point of view—but in Landscape Gardening, which is a copy of natural scenery, the foreground is constantly changing and becomes middle ground or distance as the spectator advances. In coloring too, they may differ, for the coloring which a painter would employ to give truth to a view in America, would not be such as would be proper to paint one in Italy, or France, where the masters in landscape have studied. . . . But whatever may be the difference which exists between these two arts [painting and landscape gardening], Landscape Gardening may be considered as claiming the superiority both in beauty and utility, and is, in the language of a French author, ‘à la poesie et a la peinture ce que realité est a la description et l’original a la copie.’...

- “The Landscape Gardener who possesses taste, will of course avoid both extremes and follow nature in her simplicity, symmetry, variety and beauty. He will avoid, on the one hand, the absurdity of clipping trees into formal figures, and cutting hedges so as to resemble walls, and disposing gardens in the shape of the human body, as has been done; and, on the other, the equally censurable extreme of giving every thing the form of a curve, which, though the imaginary line of beauty, becomes tame and monotonous when carried to an extreme. By the improver of taste, a union of the old and modern style may be made to produce a harmonious and happy effect. . . .

- “The Landscape Gardener is always the most successful when he makes his work appear to be the exclusive work of nature. It is that which constitutes his excellence and the beauty of his work. . . . The principal aim of the Landscape Gardener is to create the picturesque and beautiful and but rarely the sublime—unless the genius loci will admit of it. But the wild and romantic are seldom within the range of human habitations. . . . This is just a designation of the business of a Landscape Gardener, whose aim, moreover, should be the attainment of the highest degree of beauty which his own imagination can suggest, or the genius of the place and the circumstances of the proprietor will admit of.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (pp. 339–40) [20]

- “A taste for landscape-gardening, like that for the higher order of painting, sculpture and other fine arts, is the slow product of wealth and easy leisure, and is distinct from a love of flowers evinced alike by the young and the aged, the intellectual and the illiterate. In the United States, as might be expected in a new country, the mass are too busily engaged in the every day cares of life to devote attention to such objects—but few comparatively, ‘the architects of their own fortunes,’ have acquired the means to indulge in luxurious expenditures. We are, however, acquiring taste on this and kindred subjects, and with the increasing wealth, the general education and superior intelligence which characterize the American people, there can be no doubt that long before we can be called an old nation, our tastes will have been refined, and our capacity to appreciate the beautiful largely developed. Already we have evidence of ‘the march of improvement,’ as exhibited in the pretty cottages, with their decorated grounds, around our towns and cities; an onward step towards that which in portions of Europe, especially in England, gives such charm to the country, and to country life.

- “Those who wish to consult works on Landscape Gardening and Rural Architecture, almost indivisible, are referred to Loudon’s ‘Encyclopedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture,’ Loudon’s ‘Suburban Gardener,’ Downing’s ‘Landscape Gardening,’ Downing’s ‘Cottage Residences,’ &c.”

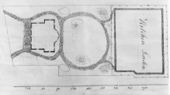

- Thomas, John J., April 1848, “The Shrubbery and Flower Garden” (The Cultivator 5: 114) [21]

- “Nearly all the flower gardens of the country are laid out in geometrical lines; a style, it is true much better adapted to the small piece of ground allotted to flowers, than to the larger landscape garden composed of trees, lawns, and sheets of water. With a wish however, to encourage a more graceful, pleasing, and picturesque mode of laying out even the small flower garden in connexion with the shrubbery, we have given the above plan, which nearly explains itself.”

- Downing, A. J., 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (pp. 17–21, 38, 40, 66–67, 93–94, 525) [22]

- “‘Our first, most endearing, and most sacred associations,’ says the amiable Mrs. Hofland, ‘are connected with gardens; our most simple and most refined perceptions of beauty are combined with them.’ And we may add to this, that Landscape Gardening, which is an artistical combination of the beautiful in nature and art—an union of natural expression and harmonious cultivation—is capable of affording us the highest and most intellectual enjoyment to be found in any cares or pleasures belonging to the soil.

- “The development of the Beautiful is the end and aim of Landscape Gardening, as it is of all other fine arts. The ancients sought to attain this by a studied and elegant regularity of design in their gardens; the moderns, by the creation or improvement of grounds which, though of limited extent, exhibit a highly graceful or picturesque epitome of natural beauty. Landscape Gardening differs from gardening in its common sense, in embracing the whole scene immediately about a country house, which it softens and refines, or renders more spirited and striking by the aid of art. In it we seek to embody our ideal of a rural home; not through plots of fruit trees, and beds of choice flowers, though these have their place, but by collecting and combining beautiful forms in trees, surfaces of ground, buildings, and walks, in the landscape surrounding us. It is, in short, the Beautiful, embroided in a home scene. . . .

- “This embellishment of nature, which we call Landscape Gardening, springs naturally from a love of country life, an attachment to a certain spot, and a desire to render that place attractive— a feeling which seems more or less strongly fixed in the minds of all men. But we should convey a false impression, were we to state that it may be applied with equal success to residences of every class and size, in the country. Lawn and trees, being its two essential elements, some of the beauties of Landscape Gardening may, indeed, be shown wherever a rood of grass surface, and half a dozen trees are within our reach; we may, even with such scanty space, have tasteful grouping, varied surface and agreeably curved walks; but our art, to appear to advantage, requires some extent of surface—is lines should lose themselves indefinitely, and unite agreeably and gradually with those of the surrounding country.

- “In the case of large landed estates, its capabilities may be displayed to their full extent, as from fifty to five hundred acres may be devoted to a park or pleasure grounds. Most of its beauty, and all its charms, may, however, be enjoyed in ten or twenty acres, fortunately situated, and well treated; and Landscape Gardening, in America, combined and working in harmony as it is with our fine scenery, is already beginning to give us results scarcely less beautiful than those produced by its finest efforts abroad. The lovely villa residences of our noble river and lake margins, when well treated—even in a few acres of tasteful foreground,—seem so entirely to appropriate the whole adjacent landscape, and to mingle so sweetly in their outlines with the woods, the valleys, and shores around them, that the effects are often truly enchanting.

- “But if Landscape Gardening, in its proper sense, cannot be applied to the embellishment of the smallest cottage residences in the country, its principles may be studied with advantage, even by him who has only three trees to plant for ornament; and we hope no one will think his grounds too small, to feel willing to add something to the general amount of beauty in the country. . . .

- “Landscape Gardening is, indeed, only a modern word, first coined, we believe, by Shenstone, since the art has been based on natural beauty; but as an extensively embellished scene, filled with rare trees, fountains, and statues, may, however artificial, be termed a landscape garden, the classical gardens are fairly included in a retrospective view. . . .

- “On the continent of Europe, though there are a multitude of examples of the modern style of landscape gardening, which is there called the English or natural style, yet in the neighborhood of many of the capitals, especially those of the south of Europe, the taste for the geometric or ancient style of gardening still prevails to a considerable extent. . . .

- “With regard to the literature and practice of Landscape Gardening as an art, in North America, almost everything is yet before us, comparatively little having yet been done. Almost all the improvements of the grounds of our finest country residences, have been carried on under the direction of the proprietors themselves, suggested by their own good taste, in many instances improved by the study of European authors, or by a personal inspection of the finest places abroad. The only American work previously published which treats directly of Landscape Gardening, is the American Gardener’s Calendar, by Bernard McMahon of Philadelphia. . . .

- “The early writers on the modern style were content with trees allowed to grow in their natural forms, and with an easy assemblage of sylvan scenery in the pleasure-grounds, which resembled the usual woodland features of nature. The effect of this method will always be interesting, and an agreeable effect will always be the result of following the simplest hints derived from the free and luxuriant forms of nature. No residence in the country can fail to be pleasing, whose features are natural groups of forest trees, smooth lawn, and hard gravel walks.

- “But this is scarcely Landscape Gardening in the true sense of the word, although apparently so understood by many writers. By Landscape Gardening, we understand not only an imitation, in the grounds of a country residence, of the agreeable forms of nature, but an expressive, harmonious, and refined imitation. In Landscape Gardening, we should aim to separate the accidental and extraneous in nature, and to preserve only the spirit, or essence. This subtle essence lies, we believe, in the expression more or less pervading every attractive portion of nature. And it is by eliciting, preserving, or heightening this expression, that we may give our landscape gardens a higher charm, than even the polish of art can bestow.

- “Now, the two most forcible and complete expressions to be found in that kind of natural scenery which may be reproduced in Landscape Gardening, are the BEAUTIFUL and the PICTURESQUE....

- “In the majority of instances in the United States, modern style of Landscape Gardening, wherever it is appreciated, will, in practice, consist in arranging a demesne of from five to some hundred acres,—or rather that portion of it, say one half, one third, etc., devoted to lawn and pleasure-ground, pasture, etc.—so as to exhibit groups of forest and ornamental trees and shrubs, surrounding the dwelling of the proprietor, an extending for a greater or less distance, especially towards the place of entrance from the public highway. Near the house, good taste will dictate the assemblage of groups and masses of the rarer or more beautiful trees and shrubs; commoner native forest trees occupying the more distant portions of the grounds.”

- Ranlett, William H., 1849, The Architect ([1849] 1976: 1:3–4) [23]

- “While the products of Painting and Sculpture are necessarily limited and selfish in their effects— being shut in from public gaze, and designed to gratify only the proprietor and his chosen friends and guests—Landscape Gardening is claimed as producing a far greater amount of public good, by spreading its beauties before the public eye— allowing the rich and the poor alike to look upon them and be delighted. . . .

- “Landscape Gardening was, formerly, the imitation of geometric figures; hence the ancient mode of it is called the geometric style of gardening.”

- Loudon, J. C., 1850, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 329) [24]

- “841. Landscape-Gardening is practised in the United States on a comparatively limited scale; because, in a country where all men have equal rights, and where every man, however humble, has a house and garden of his own, it is not likely that there should be many large parks.”

- Ranlett, William H., 1851, The Architect ([1851] 1976: 2:38–40) [23]

- “The art of landscape gardening is an essential part of the accomplishments of an architect, for the main beauty of a rural dwelling is its harmonizing with the scene of which it forms a part. The same house that looked picturesque and beautiful on the top of a hill would look extravagant and whimsical on a plain; a country house with a southern front should have a projecting roof and a piazza; but one fronting the north would look more cold and cheerless by the addition of an overhanging roof or a veranda. Yet nothing is more common than to see houses in the country with gloomy-looking piazzas on the north side which is always in shadow, while the back part is left to scorch in the sun without even the protection of a hooded window to cast a shadow. . . .

- “A good many of the cottages and villas in the suburbs of our large towns appear to have been transferred from old landscapes and picture-books, and it is not unlikely that their proprietors understood ‘landscape gardening’ to mean the imitation of landscape paintings. . . . As copies of Claude’s landscapes are rather more frequently brought over here than those of Gaspar Poussin, we hope that those who prefer going to a painted landscape for a design of a country house to employing an intelligent architect to furnish one, will give the preference to Claude, as his architectural embellishments are infinitely more beautiful than the gloomy looking villas and castles in the landscapes of Poussin. But the better way will be to avoid both, and call in the aid of a professed architect.”

- Meehan, Thomas, February 1852, “Notes on Landscape Gardening” (Horticulturist 7: 92)

- “Landscape gardening, to be pleasing, must be accommodating. Nature herself, is so. In the plains she will give the Oak, the Beech, the Birch, a giant height and strength; on the hill sides and elevations she checks their luxuriance—while on the mountain summits she reduces them to the rank of mere bushes. They, therefore, who follow the ‘natural style,’ may learn from this, that its results depend on their application of natural laws, rather than on any abstract formulas of lines or circles. Mankind generally run into extremes. Landscape gardening confirms this truth. The old system of squaring all walks, carrying them at right lines and angles, shearing and clipping every tree, and making everything so exactly correspondent, was so very absurd.”

Images

Inscribed

J. C. Loudon, In planting with a view to natural beauty, in An encyclopædia of gardening (1826), p. 1008, fig. 691.

Anonymous, "Example of the beautiful in Landscape Gardening," in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), pl. opp. p. 273, fig. 15.

Anonymous, "Example of the Picturesque in Landscape Gardening", in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), pl. opp. p. 273, fig. 16.

Associated

William Russell Birch, "The View from Springland," 1808, in William Russell Birch and Emily Cooperman, The Country Seats of the United States (2009), p. 45, pl. 2.

James Smillie (artist), J. A. Rolph (etcher), "View of the Forest Pond, Mount Auburn Cemetery," in Cornelia W. Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated ([1847] 1850), opp. p. 94.

Anonymous, "View in the Meadow Park at Geneseo," in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 3, no. 4 (October 1848): pl. opp. p. 153.

Andrew Jackson Davis, "View in the Grounds at Blithewood," in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), frontispiece.

Anonymous, "View in the Grounds at Hyde Park" in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), p. 45, fig. 1.

Thomas Chambers, Mount Auburn Cemetery, mid-19th century.

A. J. Downing, Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington, 1851. See copy.

A. J. Downing, Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington, 1851. Manuscript copy by Nathaniel Michler, 1867.

Attributed

Notes

- ↑ A vast amount of literature exists, of both primary and secondary references, regarding landscape gardening. See John Dixon Hunt and Peter Willis, eds., The Genius of Place: The English Landscape Garden 1620–1820 (London: Paul Elek, 1975), view on Zotero, for more about the movement in the eighteenth century. Also see Mark Laird, The Flowering of the Landscape Garden: English Pleasure Grounds, 1720–1800 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Doveton Nichols and Ralph E. Griswold, Thomas Jefferson, Landscape Architect (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1978), 83–86, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Henry Latrobe, The Virginia Journals of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1795-1798, ed. by Edward C. Carter II, 2 vols (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1977), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Emily Tyson Cooperman, "William Russell Birch (1755-1834) and the Beginnings of the American Picturesque" (unpublished Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1999), view on Zotero/

- ↑ Thaddeus William Harris, A Discourse Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on the Celebration of Its Fourth Anniversary, October 3, 1832 (Cambridge, Mass.: E. W. Metcalf, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kenneth Hawkins, "The Therapeutic Landscape: Nature, Architecture, and Mind in Nineteenth-Century America" (unpublished Ph.D. diss., University of Rochester, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Cleaveland, Green-Wood Illustrated: In Highly Finished Line Engraving, from Drawings Taken on the Spot/by James Smillie/With Descriptive Notices, by Nehemiah Cleaveland (New York: R. Martin, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th edn (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, "The State and Prospects of Horticulture", The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, 6 (1851), 537–41, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Whately, Observations on Modern Gardening, 3rd edn (London: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Gregory, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, First American, from the second London edition, considerably improved and augmented, 3 vols (Philadelphia: Isaac Peirce, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, An Inaugural Discourse, Delivered before the New-York Horticultural Society at Their Anniversary Meeting, on the 31st of August, 1824 (New York: J. Seymour, 1824), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th edn (London: Longman et al, 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ H.A.S. (Henry Alexander Scammell) Dearborn, An Address Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (Boston: J.T. Buckingham, 1833), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. Loudon, "Review of Practical Hints on Landscape Gardening", The Gardener’s Magazine and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement, 8 (1832), 700–702, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, New ed., considerably improved and enlarged (London: Longman et al, 1834), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, "Landscape Gardening", The Horticultural Register and Gardener’s Magazine, 3 (1837), 121–31, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edgar Allan Poe, "The Landscape-Garden", Ladies’ Companion, 17 (1842), 324–27, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Watterston, "Landscape Gardening", Southern Literary Messenger, 10 (May) (1844), 306–15, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. by David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John J. Thomas, "The Shrubbery and Flower Garden", The Cultivator: A Monthly Publication, Devoted to Agriculture., 5 (1848), 114–16, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th edn (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 William H. Ranlett, The Architect, 2 vols (New York: Da Capo, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed., corr. and improved (London: Longman et al., 1850), view on Zotero.