David Hosack

Overview

Birth Date: August 31, 1769

Death Date: December 22, 1835

Role: Physician

Used Keywords: Bed, Botanic garden, Bridge, Cemetery/Burying ground/Burial ground, Clump, Conservatory, Eminence, Ferme ornée/Ornamental farm, Flower garden, Gate/Gateway, Greenhouse, Grove, Hothouse, Kitchen garden, Landscape gardening, Lawn, Orchard, Park, Parterre, Pavilion, Piazza, Picturesque, Pleasure ground/Pleasure garden, Seat, Square, Sundial, Temple, Terrace/Slope, Thicket, View/Vista, Walk, Wood/Woods

Other resources: Library of Congress Authority File; American National Biography;

David Hosack (August 31, 1769—December 22, 1835) was a physician, botanist, educator, and cultural leader who developed the Elgin Botanic Garden in New York City, as well as an extensive private garden at his country house, Hyde Park (on the Hudson River, NY).

History

The son of a successful New York City merchant who had immigrated to America from Scotland, David Hosack was one of the best educated native-born Americans of his generation [Fig. 1]. While pursuing a classical education as an undergraduate at Columbia and Princeton, he studied medicine privately, attending lectures by Samuel Bard and other local physicians. In 1790 he entered the Medical School of the University of Pennsylvania, boarding in the home of one of his professors, Benjamin Rush, and forming a close friendship with Caspar Wistar. He received a medical degree in 1791.[1] Convinced that success as a doctor required the patina of sophistication conferred by overseas study, Hosack journeyed to Edinburgh in 1792 and spent nine months attending medical classes at the university.[2] In 1793 Hosack journeyed north to Elgin, his father’s birthplace, where he spent time with some of his relatives, as well as the Duke and Duchess of Gordon, who were in the process of carrying out landscape improvements in the manner of Lancelot “Capability” Brown at nearby Gordon Castle.[3]

Embarrassed by his ignorance of the plants he encountered in the garden of one of his professors, Hosack resolved to improve his knowledge of botany (view text).[4] In London, where he continued his medical studies after leaving Scotland, he immersed himself in English flora and learned the Linnaean system of botanic classification under the tutelage of William Curtis (1746—1799), an apothecary who conducted lessons in the field and at his botanic garden at Brompton.[5] Hosack was elected a Fellow of the Linnaean Society and began a lifelong association with the society’s president, James Edward Smith.[6] When he returned to America in 1794, he brought with him a cabinet of minerals he had begun assembling in Edinburgh, as well as colored engravings of plants and duplicate specimens from the herbarium of Carl Linnaeus, a gift from James Edward Smith (view text).[7]

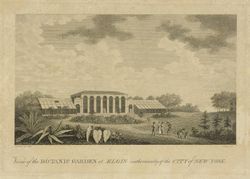

On resettling in New York, Hosack swiftly established himself as the personal physician of several politically prominent families. He was appointed professor of botany at Columbia College in 1795, adding the professorship of materia medica in 1797.[8] He was also elected to the New York Society for the Promotion of Agriculture, Arts and Manufactures. In March 1795 he wrote a letter to the group’s president, Robert R. Livingston with a detailed proposal for members “to collect and prepare a Hortus Siccus, of all the different plants. . . which grow in their respective neighborhoods. . . for the purpose of forming a complete Flora of the State” of New York.[9] Hosack’s plan failed to gain momentum, and without other resources to draw on, he fell back on his own collections in teaching his classes. In a letter of November 1797, he alerted the trustees of Columbia College to the costs he had incurred in providing books, colored engravings, and an herbarium for his students, and requested that “the professorship of botany and materia medica be endowed with a certain annual salary to defray the necessary expenses of a small garden” to serve as a teaching aid (view text). Failing to gain traction with the college, he took the matter up with the state legislature in 1800, and when that petition failed, too, Hosack used his own funds to purchase twenty acres of land on which to establish a botanic garden in 1801 [Fig. 2].

Named for his father’s birthplace in Scotland, the Elgin Botanic Garden was an ambitious undertaking and proved a steady drain on Hosack’s finances. When he finally sold the garden to the state of New York in 1811, the price fell $28,000 short of his expenditures on the property.[10] The state of neglect that set in almost immediately was a source of frustration and disappointment to Hosack, who had entertained plans to document the botanic garden in a multi-volume illustrated publication, American Botany, or a Flora of the United States, modeled on James Edward Smith’s English Botany (36 vols., 1790—1814), as well as in a periodical modeled on William Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, with the German botanist Frederick Pursh serving as editor.[11] Several of Hosack’s young protégés went on to become eminent botanists, among them John Torrey (1796—1873) and Alire Raffeneau-Delile (1778—1850).[12]

Hosack entered into a professional partnership with his mentor Samuel Bard around 1795, assuming sole responsibility for the practice upon Bard’s retirement in 1799. Having tended victims of yellow fever in 1795 and 1798, Hosack promoted new procedures for preventing and treating contagious diseases, including visionary city planning measures, such as eliminating narrow streets and alleys and lining walks and cemeteries with specific types of trees to provide shade, purify the air, and beautify the city (view text). Hosack also took a great interest in New York’s cultural life. His home functioned as a salon where American writers and artists mingled with physicians and scientists. Hosack’s extensive art collection was similarly eclectic, mixing contemporary American landscape painting, such as John Trumbull’s Niagara Falls, from Two Miles Below Chippawa [Fig. 3], with Italian Old Masters. Among the artists patronized by Hosack was the young English painter Thomas Cole (1801—1848), who immigrated to America in 1818 and became one of the founders of the Hudson River School of landscape painters. In November 1826 Hosack sent Cole a printed invitation requesting his company “Sunday evenings, during the winter.”[13] Three years later, Hosack purchased Cole’s Biblical landscape painting, Expulsion from the Garden of Eden [Fig. 4].

That same year, Hosack made a far more extravagant purchase, acquiring the principal section of Hyde Park, the Hudson River estate of his deceased partner Samuel Bard. Hosack thereafter retired to his new country seat, devoting the rest of his life to carrying out an ambitious plan for landscaping the grounds. The estate became well known for its dramatic views of the Hudson River, and for the elaborate network of gardens, walks, and drives that Hosack laid out there. Attracted by the international fame of Hyde Park as one of America’s finest estates, and by Hosack’s reputation for generous hospitality, tourists invariably stopped off while touring the Hudson River valley. Hyde Park became a favorite subject of travel accounts and works of art, which provide far more detailed information about the design of the grounds than is generally the case for early 19th-century gardens.

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Hosack, David, n.d., recalling travels in Scotland and England in 1793—94 (1861: 297—98)[14]

- “Having. . . upon one occasion—while walking in the garden of the Professor Hamilton, at Blandford [possibly Blackford], in the neighborhood of Edinburgh,—been very much mortified by my ignorance of botany, with which his other guests were familiarly conversant, I had resolved at that time, whenever an opportunity might offer, to acquire a knowledge of that department of science. Such an opportunity was now presented, and I eagerly availed myself of it. The late Mr. William Curtis, author of the 'Flora Londinensis,' had at that time just completed his botanic garden at Brompton, which was arranged in such manner as to render it most instructive to those desirous of becoming acquainted with this ornamental and useful branch of a medical education. Although Mr. Curtis had for some time ceased to give lectures on botany, he very kindly undertook, at my solicitation, to instruct me in the elements of botanical science. For this purpose I visited the botanical garden daily throughout the summer, spending several hours in examining the various genera and species to be found in that establishment. I also had the benefit, once a week, of accompanying him in an excursion to the different parts of the country in the vicinity of London, Dr. William Babington, Dr. [Robert John] Thornton, Dr. now Sir Smith Gibbs, Dr. [John] Hunter of New York, the Hon. Mr. [Charles Francis] Greville, and myself, composed the class in these instructive botanical excursions, in the summer of 1793.

- “By Mr. [James] Dickson, of Covent Garden, the celebrated cryptogamist, . . . I was also initiated into the secrets of the cryptogamic class of plants.

- “In the spring of 1794, I also attended the public lectures of botany delivered by the president of the Linnean Society, Dr., now Sir James Edward Smith ; and by the kindness of the same gentleman, I had access to the Linnaean Herbarium. I spent several hours daily for four months examining the various genera, and the most important species contained in that extensive collection. Notwithstanding my attention to botany, I was not unmindful of the other departments of medicine.” back up to History

- Hosack, David, September 8, 1794, letter to Benjamin Rush (quoted in Robbins 1964: 29)[15]

- “[I have] made many sacrifices for providing the necessary materials for promoting [natural history]: an extensive Library, chemical apparatus, an Herbarium and a collection of necessary objects of natural history as mineralogy.”

- Hosack, David, November 1797, memorial presented to the President and Members of the Board of Trustees of Columbia College (1811: 7—8)[16] back up to History

- “It has been to me a source of great regret that the want of a Botanical Garden, and an extensive Botanical Library, have prevented that advancement in the interests of the institution which might reasonably have been expected. . .

- “To this end, I have purchased for the use of my pupils such of the most esteemed authors as are most essential in teaching the principles of Botany; and at a considerable expense I have been enabled to procure a large and very extensive collection of coloured engravings; but the difficulty of teaching any branch of natural philosophy, and of philosophy, and of rendering it interesting to the pupil, without a view and examination of the objects of which it treats, will readily be perceived: it will also occur to you that books, or engravings, however valuable and necessary, are of themselves insufficient for the purposes of regular instruction in medicine.

- “The obvious and only effectual remedy would be the establishment of a Botanical Garden: this would invite a spirit of inquiry. The indigenous plants of our country would be investigated, and ultimately would promise important benefits, both to agriculture and medicine. . . I beg leave to suggest. . . that the professorship of botany and material medica be endowed with a certain annual salary, sufficient to defray the necessary expenses of a small garden, in which the professor may cultivate, under his immediate notice, such plants as furnish the most valuable medicines, and are most necessary for medical instruction.”back up to History

- Bard, Samuel, February 27, 1799, letter from Hyde Park to Sally Bard in New York (Langstaff 1942: 200)[17]

- “I beg you or Dr. Hosack will write to Mr. Prince at Flushing for twelve good roots of the sweet scented monthly Honeysuckle to be sent immediately to you at Doctor Hosack’s so that you may send them by the first boat of which you shall have notice hence. Your letter is to be sent to the house formerly Gains book store Hanover Square [New York] where get for me one of Princes last catalogues & send to me with the plants—by no means neglect this immediately, we do not know how soon the river will open.”

- Pursh, Frederick, 1814, describing Elgin Botanic Garden, New York, NY (1814: xiv)[18]

- “While I was engaged in arranging my materials for this publication, I was called upon to take the management of the [Elgin] Botanic Garden at New York, which had been originally established by the arduous zeal and exertions of Dr. David Hosack, Professor of Botany, &c. as his private property, but has lately been bought by the Government of the State of New York for the public service. As this employment opened a further prospect to me of increasing my knowledge of the plants of that country, I willingly dropped the idea of my intended publication for that time, and in 1807 [sic; 1809] took charge of that establishment.

- “Here I again endeavoured to pay the utmost attention to the collection of American plants, as the establishment was principally intended for that purpose. In this I was supported by my numerous botanical connections and friends, among whom I must particularly mention John Le Conte, Esq. of Georgia, whose unremitting exertions added considerably to the collection, particularly of plants from the Southern States.

- “The additions to my former stock of materials for a Flora were now considerable, and in conjunction with Dr. D. Hosack I had engaged to publish a periodical work, with coloured plates, all taken from living plants, and if possible from native specimens, on a plan similar to that of Curtis’s Botanical Magazine; for which a great number of drawings were actually prepared. But. . . in 1810, took a voyage to the West Indies, . . . from which I returned in the autumn of 1811.

- “On my return to New York, I found things in a situation very unfavourable to the publication of scientific works, the public mind being then in agitation about a war in Great Britain. I therefore determined to take all my materials to England, where I conceived I should not only have the advantage of consulting the most celebrated collections and libraries, but also meet with that encouragement and support so necessary to works of science, and so generally bestowed upon them there.”

- Hosack, David, 1820, recommendations for city planning as defense against contagious disease (1820: 42—43)[19]

- “Enclosing such cemeteries by trees which vegetate early, and continue their foliage late in the autumn, will also greatly contribute to preserve the purity of the air, and afford to such enclosures all the advantages to be derived from public squares. Here, too, it may be remarked, that the practice of planting trees throughout the city, especially on the sidewalks of our widest streets, should be recommended, if not made the subject of an ordinance by our Corporation; for certainly there is no measure so directly conducive to the general purity of the atmosphere, at the same time that it furnishes a defence from the rays of the sun, as the foliage of our largest trees, particularly the plane-tree—the horse—chesnut—the elm—the lime, or linden—the black walnut, and the catalpa, which, while they promote the health of the inhabitants, constitute no inconsiderable addition to the beauty of the city.” back up to History

- Hosack, David, August 31, 1824, An inaugural discourse, delivered before the New-York Horticultural Society (1824: 11—26)[20]

- “The strong attachment, which from my youth I have cherished for botanical and horticultural pursuits, in connexion with an ardent desire to advance the interests of this excellent institution, will not permit me to decline the honour you have this day conferred upon me [by electing me president]. . .

- “Horticulture embraces three objects. 1st. The cultivation of the plants of the table, including culinary vegetables and fruits. 2d. Those plants which are considered as ornamental. And 3d. Landscape gardening; or, the art of laying out grounds in such manner as may render them most conducive to utility and beauty.

- “In as far therefore as horticulture is not only subservient to utility, but, like the art of painting, addresses itself to the taste and to the imagination, it has very properly been enumerated among the liberal or the fine arts; and accordingly ranks among the most delightful and important of human pursuits. By Cicero it is with great propriety enumerated among the most pleasing occupations of the mind, peculiarly so in advanced life; at the same time that it is beneficial to health, by the agreeable exercise it affords to the body and the mental faculties. . .

- “Referring to Xenophon, to Justin, to Virgil, to Pausanias, to Pliny, and to the writers of later days, [Horace] Walpole [History of Modern Gardening, subjoined to his fourth volume of the Art of Painting], Sir William Temple, Wheatly [sic; Thomas Whately, Observations on Modern Gardening, and to Dr. [William] Falconer’s Historical View of the Gardens of Antiquity, I pass on to remark, that very little has been effected in the science of gardening, until the last fifty years. Within that period, a number of individuals, distinguished for their taste and education, have given their attention to the study of this interesting subject, and especially in France and in Great Britain, have produced important changes in every department of horticulture, including that branch of it more especially, denominated landscape gardening. In this list, the names of [Phillip] Miller, [Humphry] Marshall,[John] Abercrombie, [Robert] Brown, Nicol, [Humphry] Repton, [Richard Payne] Knight, and [John Claudius] Loudon [Encyclopaedia of Gardening] as well as others, whose taste and opportunities led them to the cultivation of this art, hold a distinguished place.

- “But passing over the long and justly celebrated national establishment of France, which, under the auspices of [Pierre-François Guyot] Desfontaines, [Antoine Laurent de] Jussieu, and [André] Thouin, embraces every thing directly and remotely connected with this department of knowledge, it is to be observed that it was not until 1804 that the first association of this nature was formed in Great Britain. . . the Horticultural Society of London. . . and in 1809. . . the Caledonian Horticultural Society was formed. . .

- “But a very few years have elapsed since the Society now assembled, was first instituted. In September 1818, a small number of the more enterprising and intelligent of the practical gardeners and nurserymen in the vicinity of this city, convened for the purpose of introducing such improvements in the cultivation of our vegetable productions, as they conceived were called for, and which, by their education and abilities, they felt themselves competent to effect. This association was in the first instance entered into without the most distant view of attracting public notice. But as these improvements proceeded, they acquired notoriety, and the views of their authors expanded with their success. They consequently became desirous that the knowledge of the improvements they had effected might be preserved and extended for the good of the community. Many of the most respectable gentlemen of our city, who are in the habit of passing a portion of their time, during the warm season of the year, at their villas in the neighbouring country, and who are attached to horticulture, also joined in this association. . .

- “Such, gentlemen, were the humble and unostentatious beginnings of the New-York Horticultural Society, which, within a very short space of time, has been the means of increasing the variety, and of improving the quality of the vegetables of our table; of totally changing the face of our markets; of introducing a great number of valuable fruits; of augmenting the number and variety of ornamental plants, both indigenous and exotic, and thereby of spreading a taste for this innocent, yet instructive and delightful source of enjoyment. . .

- “While these measures were in progress, owing to a train of unpleasant circumstances, the recollection of which we hope may never be revived, a few gentlemen thought it expedient to form a new establishment, under the title of the New-York State Horticultural Society, and precisely, as they themselves set forth, for similar purposes in all respects with those of the original institution now in successful operation, and under which we are happily assembled. I well know that the greater number of those who entered into the new association were, at the time they expressed their willingness to concur in its establishment, altogether uninformed of the ulterior views and proceedings of the already existing society, and have since expressed their desire that the two associations may be consolidated and their entire willingness to lend their aid in effecting such union. . .

- “As this Institution is altogether of a practical nature, and has for its objects practical improvements in the culture of plants, it is obvious that a garden should be established in the vicinity of this city, as a repository for the vegetable productions that maybe received by the Society, whether derived from foreign countries, or the growth of our own soil. As subservient to great purposes for which this Society has been instituted, and as already stated, these objects are numerous, a piece of ground should be selected, which, from its extent, variety, and situation, would be capable of affording all the advantages that can be contemplated in an establishment of this nature.

- “1st. It should be sufficiently extensive to contain all the variety of fruit-trees and shrubs, not only that they may have all the advantages of space necessary to their growth, but that they may be exhibited to the visitor or cultivator under the most advantageous circumstances. . .

- “2d. Compartments should be provided for all the esculent vegetables of the table, in whatever form they may exist, whether gramineous or herbaceous.

- “3d. Provision should be made for the culture of those plants that are most useful in medicine, or are subservient to the arts, or are employed in manufactures.

- “4th. To these should be added, for the purpose of diffusing a taste for the productions of nature, and of exciting the attention of our youth of both sexes to botanical inquiries, and of contributing to the beauty and elegance of the establishment, a collection of the most rare and ornamental plants that can be procured, both indigenous and exotic. While therefore we shall thus have it in our power to bring into one view, for the information of the stranger or for the purposes of exchange with foreign correspondents of the Institution, the native productions of our varied climate and country, we should also be provided with suitable conservatories for those plants which may be introduced from abroad. And I may add, that the buildings thus erected should be constructed agreeably to the most correct principles of architecture; for every such edifice, in a place of great public resort, will necessarily have its influence in forming and directing the general taste of the country.

- “5th. The whole of this Institution should be surrounded with a belt of forest trees and shrubs, foreign and domestic.

- “6th. Connected also with these means of instruction, a building should be set apart, appropriated as a Lecturing Room, and supplied with a Library, where access may be had to every work of importance, in any of the branches appertaining to the subjects of botany, horticulture, vegetable physiology, the philosophy of vegetation, or the principles of agriculture; and in forming such library, you will not omit to place upon its shelves the Memoirs and Transactions of the London and Edinburgh Horticultural Societies, as well as those of France and other establishments of the like nature on the continent of Europe; the transactions of the agricultural institutions of this country—of the states of Pennsylvania, New-York, Massachusetts; and the writings of [John Stuart] Skinner, Southwick, [James] Thacher, [William] Coxe, Dean[sic; Samuel Deane], [John] Taylor, [Stephen] Elliott, Nicholson, and others, should be included in such collection.

- “7th. Attached to this library, should be a cabinet set apart for an Hortus Siccus, or Herbarium, and containing our most valuable plants, preserved, arranged, and designated, in the manner that has been adopted by professor Desfontaines, at the Jardin des Plantes at Paris.* The remark I have heard made by that distinguished practical botanist, the late Sir Joseph Banks, that even an imperfect dried specimen is preferable to the best painting, is a striking evidence of the importance of such collection. Nevertheless, the productions of the pencil, in delineating the most rare and valuable plants of the garden, should be also carefully collected, as preparatory to the publications which may hereafter issue from this establishment. . .

- “8th. Another advantage which such an establishment should possess, is that of exemplifying the principles of Ornamental Planting, or Landscape Gardening. The ground should be selected of such form and variety as will admit of such decoration. And in the cultivation of the various plants of the collection, their distribution may ever be rendered subservient to this great object, and thereby become the means of spreading extensively among our citizens a taste for one of the highest recreations that the human heart can receive, and one which will go far in the improvement of the moral principle, and in diverting the mind from pursuits of a less worthy nature; for the mind that is not actively engaged in virtuous pursuits will most probably be occupied with those of a contrary character.

- “9th. In this Institution, doubtless, attention will be given in forming a system of instruction necessary in the education of the complete gardener, in the manner that has been constantly practised in some of the institutions of Europe. For this purpose, apprentices should be received for a certain period of time, affording them the advantages not only of being instructed in the cultivation of all sorts of culinary and ornamental plants, but of being made practically acquainted with the different operations of pruning, training, budding, grafting, layering, and transplanting, as well as the general principles of ornamental gardening.

- “A professor of drawing should be attached to the establishment, whose duties should be, not only to make delineations of any plants of great value or beauty that may be introduced into the collection, but who would also deliver a course of lectures upon his art, to the pupils who might resort to this establishment for instruction.

- “Instead then of looking to Europe for gardeners, which has hitherto been the custom of our country, we should at such school educate a sufficient number of our own citizens to supply all the wants that may be created. Another advantage that must obviously flow from such an organization, is, that the natives of our soil, being necessarily better acquainted with the climate and the vicissitudes of our seasons, are consequently, with the same opportunities of education, better qualified for the duties of their occupation than the foreign gardener, who requires the residence of years to instruct him in this important part of his profession.”

- Hosack, David, January 1, 1829, to Dr. James Thacher (O’Donnell et al. 1992: 29)[21]

- “I have lately purchased a farm of 700 acres on the Hudson. . . where I propose to pass my summers—my winters will be spent in town and my time devoted to the college and to my practice as far as I can render it in consultation . . . agriculture and horticulture will now occupy the residue of my life in which I follow your example—I hope you will gratify me by a visit in the summer when we will attend to the georgics as well as to medicine.” [Fig. 5]

- Gordon, Alexander, 1832, “Notices of Some of the Principal Nurseries and Private Gardens in the United States of America, Made during a Tour through the Country, in the Summer of 1831” (1832: 282)[22]

- “There is an immense number of gentlemen’s seats situated on the banks of this beautiful river [the Hudson]; but, as it respects gardening, every thing about them is on a confined scale. . . ; and although the remains of the possessions of the old aristocracy were visible, yet the ancient manor houses were falling to decay; the trees of the parks and pleasure grounds were all neglected; and rank grass and weeds covered the walks &c.

- “Hyde Park, on the Hudson.—As exception to this forlorn state of former greatness, or rather former extent, I can, with the greatest propriety, mention the splendid mansion and seat of Dr. David Hosack, a gentleman well known in the literary and scientific world (the Sir Joseph Banks of America). The doctor has lately retired from business and the city, to this delightful spot, Hyde Park. Our Hyde Park, on this side the water, can bear no comparison with its namesake on the other side of the Atlantic; its natural capacity for improvement has been taken advantage of in a very judicious manner; every circumstance has been laid hold of, and acted upon, which could tend to beautify or adorn it. The park is extensive; the rides numerous; and the variety of delightful distant views, embracing every kind of scenery, surpasses any thing I have ever seen in that or in any other country. I had the pleasure of riding round the whole with its most amiable owner, than whom a more condescending and affable gentleman is not in existence. The pleasure grounds are laid out on just principles, and in a most judicious manner; there is an excellent range of hot-houses, with a collection of rare plants; remarkable for their variety, their cleanliness and their handsome growth. The whole of this department is under the care of Mr. Hobbs, an English gardener, who well understands his business; and it was most gratifying to me to find Dr. Hosack so justly appreciating his merits. The farm buildings have been recently erected; and their construction and arrangement deserve the strongest praise; but in fact, every thing connected with Hyde Park is performed in a manner unparalleled in America; at least, as far as my observations extended.”

- Pintard, John, April 14 and June 9, 1832, letters to his daughter, Eliza Noel Pintard Davidson (1940 4:39, 63)[23]

- “Philip [Hone] lives in the genteelest style of any man in our city, not excepting Dr. Hosack, who I believe latterly has restricted his hospitality to strangers very much. Before he married the rich widow [of] H.A. Coster, with whom he got $300,000, Hosack maintained a character for general hospitality to strangers, esp. literary, for wh. I have him great credit. I was then very intimate with him, but not since the decease of Govr. Clinton have I had the slightest intercourse, no longer being serviceable to him. So the world changes. So wealth shows the natural disposition. He cultivates at great expense with great taste a Ferme ornee at Hyde Park in Duchess Co. on the Hudson formerly Dr. Bards, of several hundred acres on wh. He has lavished great sums that can never be replaced to his Heirs. . . .

- “Dr. Hosack has gone for the summer to his Ferme ornée at Hyde park.”

- “July 9th, 1832. The curtain [of mist and rain] lifted as we passed thro’ the Highlands. . . The woods and grassy slopes, green lawns and bright yellow wheat fields on either hand warmed into a richer glow with the freshening moisture of the morning. . . At half past one P.M. I went on shore at Hyde Park Landing, found a baggage waggon to take up my trunk and cloak to Dr. Hosack’s, and then followed on foot thro’ the Park gate close by the Landing. The Mansion itself was half a mile further on the brow of a bold eminence full 100 feet above the river. The ascent is gradual by broad winding walks, shaded by the richest foliage with gleams of the Hudson sparkling among the leaves—and beautiful lawns, with trees grouped in fine taste—a range of green houses and exquisite flower beds crown the ascent and sweep around a general clump of forest trees leading quite up to the house which presents a noble front to the Park. . . .After examining the Picture Gallery and the noble library occupying a whole story in one of the wings of the building, the Doctor took me over the grounds and pointed out their chief beauties. No expense has been spared in embellishing this splendid domain, which contains 800 acres of richly diversified surface—every feature of which has been made to contribute to the ornamental effect of the whole and to heighten the magnificence of the River scenery which it commands. . . The afternoon having turned out wet and unpleasant the rest of the day was spent in examining several valuable works &c. &c. my drawings, too, were brought out and handed round, and the Doctor said he wished me to make him several sketches to be engraved on stone to illustrate a Quarto which he is engaged upon descriptive of his place. . . [Fig. 6]

- [July 14] “The Doctor drove with me over the whole estate, and showed me his farming operations which he is conducting in one part of it. Rest of the day drawing. . . .

- [July 20] “Sitting with the Doctor on the Piazza after twilight I had a long conversation with him on my prospects in New York in which he kindly interests himself, and suggests plans for my advantage.

- [July 21] “Early in the morning these beautiful grounds seemed flushed with new charms as the mist rolled away from the Catskills and the sun lighted them with clear a[e]rial tints, like mother of pearl. The trees, lawns, and parterres borrowed additional brilliancy from the fresh dew, and the new mown grass smelt sweet and spicy in the still morning air. I have today completed the last of five Quarto sized drawings for the Doctor with which he is highly pleased—they are the best I can do and tinted with great care. . .

- [July 22] “Dr. Hosack will not allow a gun to be fired in or near his pleasure grounds and it is surprising what multitudes of beautiful birds, squirrels and other graceful little creatures glance about among the walks and trees—and so fearless, too, as if conscious of protection. . .

- [July 26] “Today we have a sky without a cloud. I have now finished seven drawings for the Doctor and have just washed in the first tints of a large picture. . . I may remark that the work in which he [David Hosack] is now engaged will be illustrated by the drawings I have made him, while the originals, he tells me, will be enclosed in a Portfolio and placed in the drawing room Centre Table for the frequent inspection of his family and guests.

- [July 28] “[Dr. Hosack] commenced an examination of the picture, with which he and his brother (who just then stepped in) were delighted, and suggested that it would make a valuable addition to the “gallery” and that it would prove very attractive if engraved. It is 23 ½ inches x 16 in and embraces all that splendid range of scenery northward from this Estate to the Catskills. They think I Have been particularly successful with the sky which is nearly finished and is by far the boldest effort I have yet attempted. . . I observe in the library several books of travels presented to the Doctor by Sir Joseph Banks, and many others by their respective authors, including names of great celebrity in England, among the rest “Roscoe” of Liverpool, whose “Discourses” are in the collection presented by himself. . . .”

- “I left Mr Anderson’s house for two or three days in the beginning of July to pay a visit, which I had long projected, to Dr Hosack, at his magnificent seat on the Hudson, where I was most kindly received by himself and his amiable family. He lives very much in the same style as an English country gentleman of it, can bestow. His mansion-house is large, elegant, and well-furnished; but it is not my object to describe a place laid out and embellished as a fine residence and fine grounds in England are, or to tell the readers of these pages of the size of Dr Hosack’s rooms, of his eating or drawing-rooms, his excellent library, his billiard room, or his conservatory, of his porter’s lodges, his temples, his bridges, his garden, and the other et ceteras of this truly delightful domain which he has adorned, and was, at the time when I was there, adorning with great taste and skill, and without much regard to cost. The splendid terrace over the most beautiful of all beautiful rivers, admired the more the oftener seen, renders Hyde Park, as I think, the most enviable of all the desirable situations on the river. Dr Hosack has now retired from practice as the first physician in New York. His activity is, however, unabated. He takes great delight in superintending his numerous workmen, and the management of his place and farm. He has 800 acres adjoining to his house, all, I believe, in his own occupation, and is taking great pains to obtain the finest breeds of cattle and sheep. . . His park contains deer and a few Cachmere goats, which are particularly handsome. In short, this is quite a show place, in the English sense of the word, which every foreigner should see on its own account, —on account of the great beauty of the natural terrace above the river, and the charming and varied views from it,—as well as on account of the art with which the original features of the scene are advantageously displayed. . .

- “I observed that Dr Hosack, in speaking to his workmen, never addressed them by their Christian name alone, but always in this way: 'Mr Thomas, be so good as do this,' or 'Mr Charles, be so good as do that.' It would not be easy for an Englishman of great fortune to form his mouth so as to give his orders to his servants in similar terms; but the more equal diffusion of wealth, and greater equality of condition, which prevail in this country, put the sort of submission of inferiors to superiors, to which we in Britain are accustomed, quite out of the question in the free part of the United States, and undoubtedly render the mass of the people far more comfortable, contented, and happy. . .

- “Dr Hosack’s grounds are so very charming, and the views from them so picturesque and striking, that I cannot help wishing that Captain Hall had seen Hyde Park Terrace before he declared 'North America to be the most unpicturesque country to be found anywhere.”

- “The aspect of Hyde Park from the river had disappointed me, after all I had heard of it. It looks little more than a white house upon a ridge. I was therefore doubly delighted when I found what this ridge really was. It is a natural terrace, over-hanging one of the sweetest reaches of the river; and, though broad and straight at the top, not square and formal, like an artificial embankment, but undulating, sloping, and sweeping, between the ridge and the river, and dropped with trees; the whole carpeted with turf, tempting grown people, who happen to have the spirits of children, to run up and down the slopes, and play hide-and-seek in the hollows. Whatever we might be talking of as we paced the terrace, I felt a perpetual inclination to start off for play. Yet, when the ladies and our selves actually did something like it, threading the little thickets, and rounding every promontory, even to the farthest, (which they call Cape Horn) I felt that the possession of such a place ought to make a man devout, if any of the gifts of Providence can do so. To hold in one’s hand that which melts all strangers' hearts is to be a steward in a very serious sense of the term. Most liberally did Dr. Hosack dispense the means of enjoyment he possessed. Hospitality is inseparably connected with his name in the minds of all who ever heard it: and it was hospitality of the heartiest and most gladsome kind.

- “Dr. Hosack had a good library,—I believe, one of the best private libraries in the country; some good pictures, and botanical and mineralogical cabinets of value. Among the ornaments of his house, I observed some biscuits and vases once belonging to Louis XVI., purchased by Dr. Hosack from a gentleman who had them committed to his keeping during the troubles of the first French Revolution.

- “In the afternoon, Dr. Hosack drove me in his gig round his estate, which lies on both sides of the high road; the farm on one side, and the pleasure grounds on the other. The conservatory is remarkable for America; and the flower-garden all that it can be made under present circumstances, but the neighbouring country people have no idea of a gentleman’s pleasure in his garden, and of respecting it. On occasions of wedding and other festivities, the villagers come up into the Hyde Park grounds to enjoy themselves; and persons, who would not dream of any other mode of theft, pull up rare plants, as they would wild flowers in the woods, and carry them away. Dr. Hosack would frequently see some flower that he had brought with much pains from Europe flourishing in some garden of the village below. As soon as he explained the nature of the case, the plant would be restored with all zeal and care: but the lessons were so frequent and provoking as greatly to moderate his horticultural enthusiasm. We passed through the poultry-yard, where the congregation of fowls exceeded in number and bustle any that I had ever seen. We drove round his kitchen-garden too, where he had taken pains to grow every kind of vegetable which will flourish in that climate. Then crossing the road, after paying our respects to his dairy of fine cows, we drove through the orchard, and round Cape Horn, and refreshed ourselves with the sweet river views on our way home. There we sat in the pavilion, and he told me much of De Witt Clinton, and showed me his own life of Clinton, a copy of which he said should await me on me return to New York.”

Images

John Trumbull, Dr. Hosack’s Green houses, Elgin Botanic Garden, June 1806.

Anonymous, Elgin Botanic Garden, c. 1810.

William Satchwell Leney after Louis Simond, View of the botanic garden at Elgin in the vicinity of the City of New York, c. 1810.

William Satchwell Leney after Hugh Reinagle, “View of the Botanic Garden of the State of New York,” in David Hosack, Hortus Elginensis (1811), frontispiece.

Hugh Reinagle, Elgin Garden on Fifth Avenue, c. 1812.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Residence of Dr. David Hosack, Hyde Park, New York, c. 1830.

Thomas Kelah Wharton, “Greenhouse, David Hosack Estate, Hyde Park, New York,” c. 1832.

Asher Brown Durand, The Chestnut Oak on the Hosack Estate, Hyde Park, New York, 1838.

Thomas Kelah Wharton, “Euterpe Knoll Hyde Park N. York,” September 11, 1839.

Thomas Kelah Wharton, “Crystal Cove, Hyde Park. New York,” September 11, 1839.

Anonymous, "A circular pavilion," in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), p. 456, fig. 81.

Notes

- ↑ Alexander Eddy Hosack, “A Memoir of the Late David Hosack,” in Lives of Eminent American Physicians and Surgeons of the Nineteenth Century, ed. Samuel David Gross (Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1861), 290—93, view on Zotero; David Hosack, Tribute to the Memory of the Late Caspar Wistar, M.D. (New York: C. S. Van Winkle, 1818), view on Zotero; Christine Chapman Robbins, David Hosack: Citizen of New York (Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 1964), 7—8, 18—22, view on Zotero. For Hosack’s University of Pennsylvania lecture tickets, stating the name of the issuing faculty members (Benjamin Rush, William Shippen, and James Hutchinson) and the names and dates of the courses taken (Theory and Practice of Medicine; Anatomy, Surgery and Midwifery; Chemistry and Materia Medica, all 1790), see Archives General Collection, of the University of Pennsylvania, 1740—1820, UPA 3, Matriculation and Lecture Ticket Collection, University of Pennsylvania Archives.

- ↑ Hosack 1861, 293—94, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Dingwall 2012, unpag. (section 3.9); Hosack 1861, 296, view on Zotero; Robbins 1964, 25, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robbins 1964, 24, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hosack 1861, 297—98, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robinson, 1964, 29, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hosack 1861, 323, view on Zotero; Robbins 1960, 293, 299—307, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hosack 1861, 299—301, 303—304, 307—308, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robbins 1964, 54—56, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robbins 1964, 83—84, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, A Statement of Facts Relative to the Establishment and Progress of the Elgin Botanic Garden: And the Subsequent Disposal of the Same to the State of New-York (New York: C.S. Van Winkle, 1811), ix, view on Zotero; Frederick Pursh, Flora Americae Septentrionalis; Or, a Systematic Arrangement and Description of the Plants of North America, 2 vols. (London: White, Cochrane, & Co., 1814), 1:xiv; Robbins, 1964, 66—67, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Christine Chapman Robbins, “John Torrey (1796—1873) His Life and Times,” Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 95 (November/December 1968): 531, view on Zotero; Robbins 1964, 68—71; Hosack 1861, 325—26, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robbins 1964, 168, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hosack 1861, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robbins 1964, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hosack 1811, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Brett Langstaff, Doctor Bard of Hyde Park: The Famous Physician of Revolutionary Times, the Man Who Saved Washington’s Life (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1942), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Pursh, Flora Americae Septentrionalis; Or, a Systematic Arrangement and Description of the Plants of North America, 2 vols. (London: White, Cochrane, & Co., 1814), view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, Observations on Febrile Contagion: And on the Means of Improving the Medical Police of the City of New-York: Delivered as an Introductory Discourse, in the Hall of the College of Physicians and Surgeons, on the Sixth of November, 1820 (New York: Elam Bliss, 1820), view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, An inaugural discourse, delivered before the New-York Horticultural Society at their anniversary meeting, on the 31st of August, 1824 (New York: J. Seymour, 1824), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Patricia M. O'Donnell, Charles A. Birnbaum, and Cynthia Zaitzevsky, Cultural Landscape Report for Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site: Volume I: Site History, Existing Conditions, and Analysis (Boston: U.S. Department of the Interior. National Park Service, 1992), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gordon 1832, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Pintard, Letters from John Pintard to His Daughter Eliza Noel Pintard Davidson, 1816—1833, ed. Dorothy C Barck, Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1940, 4 vols. (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1940), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Kelah Wharton, “MS. Diary,” 1830–34, The New York Public Library, Manuscripts and Archives Division, ff. 137–52, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Stuart, Three Years in North America, 2 vols. (Edinburgh: Robert Cadell, 1833), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Martineau 1838, view on Zotero.