Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane

Overview

Alternate Names: Kirkbride’s Hospital; Pennsylvania Hospital for Mental and Nervous Diseases; The Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital

Site Dates: 1841–1997

Site Owner(s): Pennsylvania Hospital;

Associated People: Thomas Story Kirkbride 1841–1883, physician; Isaac Holden c. 1835–1838, architect; Samuel Sloan 1838–1841, architect; Samuel Sloan 1856–1859;

Location: Philadelphia, PA · 39° 57' 31.50" N, 75° 14' 42.36" W

Condition: Altered

Keywords: Alley; Border; Clump; Fence; Flower garden; Gate/Gateway; Greenhouse; Grove; Ha-Ha/Sunk fence; Hothouse; Icehouse; Lawn; Meadow; Park; Pleasure ground/Pleasure garden; Pond; Promenade; Rustic style; Seat; Shrubbery; Summerhouse; View/Vista; Walk; Wall; Wood/Woods; Yard

Other Resources: LOC;

The Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, opened in 1841 on a rural site on the west side of the Schuylkill River near Philadelphia, was considered one of the premiere mental asylums during the nineteenth century. In accordance with the institution’s “moral treatment” philosophy, many patients were granted daily access to the hospital’s pleasure grounds and working farm. The institution’s superintendent, Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride, believed that regular access to the outdoors was an essential component of therapeutic treatment for his patients.

History

The Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane was one of the premiere facilities for treating mental disorders during the nineteenth century, drawing residential patients from across the United States. It opened under the direction of the superintendent Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride (1809–1883), a Quaker physician who advocated for “moral treatment” therapeutic principles, arguing that patients should have regular schedules to encourage self-control, eat healthy food, exercise, and have frequent access to the outdoors.[1] The facility’s surrounding landscape became an essential component of therapeutic treatment for patients at the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, and the hospital’s design, which was popularized by Kirkbride’s 1854 treatise On the Construction, Organization and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane, influenced the designs of asylums subsequently constructed across the United States.[2]

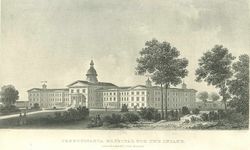

The original hospital building opened in 1841 on a 111-acre site near the village of Blockley, located on the west side of the Schuylkill River approximately two miles outside of the city of Philadelphia [Fig. 1]. This facility, located at the intersection of 44th and Market streets, took advantage of the inexpensive land, fertile soil, and increased privacy that the rural location afforded. It also provided more space and better conditions for treating mental health patients who were previously housed at the Pennsylvania Hospital in Center City Philadelphia.[3]

The first hospital building, designed by the English architect Isaac Holden (d. 1884), accommodated 160 patients. The building’s design took advantage of the site’s wooded landscape by framing picturesque views through the wards’ windows and the stone Doric porticoes erected on the eastern and western facades. As seen in this plan [Fig. 2], two smaller buildings flanked either side of the main building’s wards. These u-shaped wards were reserved for the most violent and disruptive patients, who gained access to the outdoors in interior courtyards that were surrounded on three sides by the building. Flower gardens were visible (but not physically accessible) from the fourth side.[4]

Kirkbride, who was hired by the Pennsylvania Hospital’s Board of Managers to run the new facility shortly before it opened, “played no part in the preliminary planning for the institution,” according to the scholar Nancy Tomes.[5] Because of this, the hospital did not align closely with Kirkbride’s philosophy for treating mental disorders or provide the institutional environment that he felt best served these goals. Kirkbride objected, in particular, to the layout of the hospital’s wards, and he attempted to make some modifications to the building’s design, overseeing an expansion that increased the hospital’s capacity to 250 patients by the late 1840s.[6]

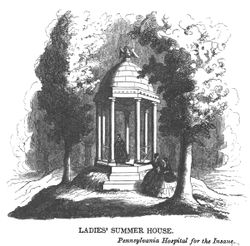

Despite his disappointment with the hospital’s built-environment, Kirkbride saw a great deal of potential in improving the grounds.[7] He considered the landscape to be an essential component of therapeutic treatment, an idea that he drew from British models that adapted “the aristocratic landscape park” to suit patients’ medical needs, as well as from the example of the Worcester State Hospital in Massachusetts.[8] As depicted in detailed plans and described by Kirkbride in his writings, he quickly laid out separate pleasure gardens for male and female patients; constructed walks, flower gardens and a vegetable garden, summerhouses, and a deer park; and oversaw the construction of a greenhouse [Fig. 3]. A ten-and-a-half-foot wall enclosed the gardens, shielding patients from the prying eyes of curious visitors and preventing patients from escaping the facility. Access to the landscape was dictated, to some degree, by a patient’s social class. More affluent patients frequently spent their days taking carriage rides through the grounds, while working-class male patients often labored in the hospital garden in exchange for reduced room and board payments. Of the 111-acre farm purchased by the hospital’s Board of Managers, approximately forty-one acres were transformed into gardens, and the remaining seventy acres of land became the hospital’s farm, where fields of grains and vegetables were cultivated to feed the inmates and a large dairy supplied the hospital with milk and cream (view text).

In 1856, due to overcrowded conditions in the existing facility, Kirkbride commissioned the architect Samuel Sloan (1815–1884) to design a second, slightly larger hospital less than one mile away from the first building on the grounds of the hospital farm at 49th Street.[9] Male patients moved into the new building [Fig. 4] in 1859, and the first hospital became dedicated to the treatment of female residents. The two hospitals were separated by a creek, and each had pleasure grounds and vegetable and flower gardens laid out in close proximity to the wards, [Fig. 5]. Outdoor space remained an essential component of psychiatric therapy at the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane.Many patients had regular access to pleasure grounds, gardens, and a deer park, and they were encouraged to walk the grounds or take carriage rides daily.[10] Those who were deemed too disruptive to access the grounds without constant supervision could only glimpse the pleasure grounds from behind bars, as shown in this illustration of patients housed in the seventh ward of the Department of Males [Fig. 6].

The Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane remained an influential medical institution in Philadelphia well into the twentieth century. The original 1841 hospital building, located on 44th Street, shuttered its doors in 1957, and the 49th Street facility, which is still extant, was sold when the institution ceased operations on the site in 1997.[11]

—Lacey Baradel

Texts

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., 1841, describing the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane (1841: 17–19)[12]

- “PLEASURE GROUND AND FARM.—Of the one hundred and eleven acres in the farm, about forty-one around the Hospital are specially appropriated as a vegetable garden and the pleasure ground of the patients, and are surrounded by a substantial stone-wall. This wall is five thousand four hundred and eighty-three feet long, and is ten and a half feet high.

- “Owing to the favourable character of the ground, the wall has been so placed that it can be seen but in a very small part of its extent, from any one position; and the enclosure is so large, that its presence exerts no unpleasant influence upon those within. Although it is probably sufficient to prevent the escape of a large proportion of the patients, that is a matter of small moment, in comparison with the quiet and privacy which it at all times affords, and the facility with which the patients are enabled to engage in labour, to take exercise, or to enjoy the active scenes which are passing around them, without fear of annoyance from the gaze of idle curiosity or the remarks of unfeeling strangers. Our location gives us the many advantages afforded by a thickly settled district, and proximity to a large city, and the wall obviates most of its disadvantages.

- "Immediately in front of the Hospital, is a lawn forming a segment of a circle, in which is a circular railroad. To the east of this, and passing into the woods, is the deer-park, surrounded by a high pallisade, and forming an effectual and not unsightly division of the ground appropriated to the different sexes; from various points of which, and from the whole eastern front of the building, it is seen to much advantage.

- “The pleasure ground is beautifully undulating, interspersed with clumps and groves of fine forest trees, and from every division of it, as well as from every room in the main Hospital, is a handsome view; either of the surrounding country and villages, the rivers in the distance, or the public roads in its immediate vicinity.

- “The groves are fitted up with seats, and are the favourite resort of the patients during the warm weather. That on the west, from the position of the wall, does not appear to be inclosed [sic], and offers full views of two public roads, of the farm and meadow, a mill race, a fine stream of running water, and two large manufactories. The grove on the east is not less pleasant, and the views from it are equally animated. This last surrounds the pond, in which is found a variety of fish.

- “On the north and south side of the building are private yards, one hundred and seventeen feet wide, and extending two hundred feet from the return wings which form one of their sides. These yards are enclosed by a tight board fence seven and a half feet high, and are surrounded with a brick pavement, which affords a fine promenade at all seasons.

- “The fences around these yards, like the wall itself, have been constructed, not so much to confine the patients, as for the sake of privacy, and to protect them from the gaze of visters [sic].

- “The remaining seventy acres, outside the wall, are cultivated by the farmer, and, with the grass obtained within it, furnish pasture and hay for the large dairy, which supplies both Hospitals with cream and milk during the whole year. From the source are also obtained some grain, and all the potatoes and other vegetables that are required in large quantities.

- “The possession of this property is of great importance to the Hospital, for the purposes just indicated; but its principal value consists in giving control of a body of land always in view from the western side of the building; and above all, in affording ample opportunities for agricultural labour to those patients who have been accustomed to such employment before entering the Hospital. Without a small farm, an insane hospital, receiving all classes of patients, cannot be perfect in its arrangements.

- “The buildings which were on the farm at the time of purchase, (in addition to the residence of the Physician within the enclosure) consist of a comfortable house for the farmer, an adjoining one for the gardener, a spring-house, an ice-house, coach-house, barn, &c., outside of the wall, and near the public entrance.” back up to History

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1841, describing the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane (1841: 1:400–01)[13]

- “The greenhouses, containing a handsome collection of exotic plants, together with the ornamental lawns in front and rear of the house, are under the care of a regular gardener. The attention paid to neatness, and even ornament, in the exterior and interior of the house, gives to the whole an air of elegance seldom equalled in establishments of this nature.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., 1844, describing the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane (1851: 24–25)[14]

- “IMPROVEMENT OF THE PLEASURE GROUNDS. – During the year just closed, the prosecution of contemplated improvements upon the forty-one acres which compose our pleasure grounds, and are within the enclosure, has also furnished a great variety of interesting employment to various classes of patients. Many trees and shrubs have been planted; flower borders have been enlarged and improved; the brick walks, for use when the ground is soft or covered with snow, have been extended; other walks have been laid out through the different groves, and covered with tan, and their extension, now in progress, will give us more than a mile in the men’s division, and nearly as much in that appropriated to the females. These walks have been so located as to embrace our finest and most diversified views, to wind through the woods and clumps of trees which are scattered through the enclosure; and among them, it is hoped, will soon be seen summer-houses, rustic seats, and other objects of interest, to tempt the patients voluntarily to prolong their walks, and to spend a greater portion of their time out of the wards, and engaged in some agreeable occupation. [Fig. 7]

- “The importance and utility of having the grounds about an insane hospital highly cultivated and improved, and everything in perfect order, is much greater than is generally supposed. It exercises a beneficial influence on all patients and on their friends. The good taste of many enables them to appreciate all such things in detail, many are pleased with them as a whole and even those who are not capable of realizing their beauties, still have an indistinct recollection of something pleasant in connexion with them. . .

- “A surprising degree of interest is frequently excited among the patients, by having everything done in the neatest and best manner, by having fixtures and apparatus of the most approved kinds, and all the buildings and arrangements showing a peculiar fitness for the purposes for which they are intended. It is where these principles are fully carried out, that a farm, a garden, and various other external matters, become truly valuable aids in the management of the insane.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., 1845, describing the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane (quoted in Hawkins 1991: 105–6)[15]

- “ . . . it would be easy in a few years to have within our enclosure, a specimen of every tree that will live in this climate, and I know of no spot near Philadelphia, where a complete arboretum could be established with less trouble, or be a subject of greater interest or more utility than upon the 41 acres which compose our pleasure ground.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., 1847, describing the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane (1851: 22)[16]

- “The general improvement of the pleasure grounds has not been neglected; the groves have been made a more pleasant resort for the patients;—new walks have been laid out, a large number of evergreen, and other trees planted, and the flower borders enlarged and beautified.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., April 1848, describing the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane (American Journal of Insanity 4: 347–53)[17]

- “The pleasure grounds and farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, as shown in the accompanying plan, comprise a tract of one hundred and ten acres of well improved land, lying two miles west of the City of Philadelphia, between the Westchester and Haverford roads, on the latter of which is the only gate of entrance.

- “Of this land, forty-one and three-quarter acres constitute the pleasure grounds, which surround the Hospital buildings, and are enclosed by a substantial stone wall, of an average height of ten and a half feet. The remaining sixty-nine and one-quarter acres comprise the farm of the Institution.

- “From the character of the ground near the Hospital, the wall surrounding the pleasure grounds is so arranged, as to be almost entirely out of sight from the buildings, and only a small part of it can be seen from any one point within the enclosure.

- “The entrance to the enclosure is through a handsome gate-way, on the west side of which is the Gate-keeper’s Lodge, and on the opposite side is a room for laying out the dead, access to which may be had from within as well as from without the pleasure grounds.

- “Carriages drive to the western front of the centre building of the Hospital that being most convenient in every respect, but the eastern is the architectural front and of most pretensions.

- “The pleasure grounds of the two sexes are very effectually separated on the eastern side, by the deer-park, surrounded by a high palisade fence, but the Park itself is so low that it is completely overlooked from both sides; and the different animals in it are in full view from the adjoining grounds used by the patients of both sexes.

- “At the extreme end of the deer-park, it is joined by the drying-yard which completes the separation of the sexes in that direction. In this yard, are the wash-house and the pump and pond from which water is raised into the tanks in the dome of the centre building. This pond is supplied from various springs on the premises, and there is ample space in the yard for drying clothes in fine weather.

- “East of the entrance is the private yard and residence of the Physician of the Institution, being the mansion house on the farm when purchased by the Hospital. The vegetable garden containing three and a half acres is next, and in it are the green-house, hot-beds, seed-houses, &c. The remainder of the grounds on this side of the deer-park is specially appropriated to the use of the male patients. In this division is a fine grove of large trees, several detached clumps of various kinds and a great variety of single trees standing alone or in avenues along the different walks, which, of brick, gravel or tan, are for the men, more than a mile and a quarter in extent. The groves are fitted up with seats and summer houses, and have various means of exercise and amusement connected with them.

- “There is a single private yard of good size for gentlemen who wish to be less public than in the grounds, or for those whose mental condition renders more seclusion desirable. This yard is planted with trees and had broad brick walks passing round it. Between the north lodge and the deer-park, separated from the latter by a sunk palisade fence, is a neat flower garden.

- “In connexion with each lodge, as now enlarged or about to be, are three small yards paved with brick, and accessible to the patients of the respective divisions with which they are connected.

- “The work-shop and lumber-yard are just within the main entrance on the west—adjoining which is a fine grove, in which is the gentlemen’s ten-pin alley.

- “In the pleasure grounds of the ladies, is a fine piece of woods, from which the farm is overlooked, as well as both of the public roads passing along the premises, and a handsome district of country beyond. The wall here is forty feet below the platform on which the Hospital stands, and is at the foot of a steep hill, so that it is not seen at all unless persons are in it’s [sic] immediate proximity.

- “The summer-houses, rustic-seats, exercising-swings &c., in this division are all in particularly pleasant positions. The cottage fronts the woods, and in every part this portion of the grounds is completely protected from intrusion and observation.

- “The undulating character of the pleasure grounds throughout, gives them many advantages, and the brick, gravel and tan walks for the ladies, are more than a mile in extent.

- “As on the men’s side, there is a private yard for females, and the flower-garden in front of the lodge, and the paved yards connected with it are similarly arranged.

- “The semi-circular yard, on the western side of the main building is surrounded by flower borders, contains the circular pleasure Rail-road, and is used at different hours, by patients of both sexes.

- “In the arrangement and location of the walks for the patients, great pains have been taken to give as much extent and variety as possible, and to bring into view objects of interest, not only within the enclosure, but in the well improved district of country immediately around the Hospital.

- “The carriage road is sufficiently extended to give a pretty thorough view of the whole grounds, and of the farm and scenery beyond. This is occasionally used very advantageously, for giving carriage exercise to patients who could not with propriety be taken to more public situations.

- “The fences that have been put up, were rendered necessary by the uses to which the different parts of the grounds were appropriated. A large part of the palisade fences, like those enclosing the deer-park and drying-yard, were to effect the separation of the sexes, and the close fences have been made, almost invariably, for the sole purpose of protecting the patients from observation, and giving them the proper degree of privacy.

- “The farm, partly meadow-land, is divided into fields of convenient size for cultivation. It has two pleasant groves on it, a stone-quarry, two good springs of water, besides Mill Creek and a mill-race, which pass through it. The residence of the farmer and gardener are outside of the enclosure, as well as the ice-house, spring-house, coach-house, barn, stabling and other arrangements for a well conducted farm.

- “An outline of the ground-plan of the Hospital and other buildings is shown on the sketch. All of these are now erected and in use, except the additions of the north and south sides of the Lodge for females, which it is hoped will be completed during the coming summer. . .

- "The cultivation of the gardens and the improvement of the pleasure grounds, offer the generality of patients the most desirable forms of labour. It is sufficiently varied, not too laborious, and in some division of it many will engage who could not be induced to assist upon the farm or in any other kind of employment, out of doors. The vegetable garden should be large enough to furnish all of that description of supplies that may be required for the institution, and may occasionally be made profitable from sales of the excess. The flower gardens should be as extensive as can be well taken care of by the inmates and persons employed in the Hospital. The good influences which these, as well as a high state of improvement about the buildings, generally produce on patients and their friends, is often of great importance.

- “If the pleasure grounds are sufficiently extensive it is desirable that the two sexes would have their portions, entirely distinct, although some parts may be used in common, under the superintendence and direction of the proper officer. Without this arrangement certain classes will be much more restricted in out-door exercise than is proper or desirable.”

Images

Thomas S. Sinclair, "Plan of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane at Philadelphia," in Thomas S. Kirkbride, American Journal of Insanity 4 (April 1848): plate opp. 280.

Anonymous, "Ladies' Summer House. Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane," in Thomas Kirkbride, Reports of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane (1851), frontispiece of "Report for 1849."

Other Resources

"A history of the Institute of Pennsylvania Hospital," Penn Medicine

Kirkbride's Hospital (National Park Service)

Notes

- ↑ “Moral treatment” grew out of asylum reform movements in England and France during the late eighteenth century. It advocated “freeing chronic patients from physical restraint and treating them as capable of rational behavior.” Nancy Tomes, A Generous Confidence: Thomas Story Kirkbride and the Art of Asylum-Keeping, 1840–1883 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 21, view on Zotero. See also Carla Yanni, The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 38, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Story Kirkbride, On the Construction, Organization and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane (Philadelphia, 1854), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Tomes 1984, 1, 5–6, 19, view on Zotero; and Yanni 2007, 38, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Holden oversaw the beginning of the building’s construction before he returned to England in 1838. After Holden’s departure, Samuel Sloan oversaw the rest of the building’s construction until its completion in 1841. Yanni 2007, 38–39, view on Zotero; and Tomes 1984, 37, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kirkbride was named superintendent on October 12, 1840. Tomes 1984, 149, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Tomes 1984, 150, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Tomes 1984, 151, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sarah Rutherford, “To Soothe and Cure Troubled Minds,” Historic Gardens Review 10 (Spring/Summer 2002): 2, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Tomes 1984, 154, view on Zotero. This later building, known as the “Kirkbride Building” and located on Forty-ninth street between Haverford and Market streets, is still extant.

- ↑ Yanni 2007, 71, 73, view on Zotero.

- ↑ See the “Historical Timeline” on the Penn Medicine’s History of Pennsylvania Hospital Website, https://www.uphs.upenn.edu/paharc/timeline/1951/.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, Report of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane: for the Year 1841 (Philadelphia: Board of Managers, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Silk Buckingham, America, Historical, Statistic, and Descriptive, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Story Kirkbride, Reports of the Pennsylvania Hospital for The Insane, with a Sketch of its History, Buildings, and Organization (Philadelphia: Published by order of the Board of Managers, 1851), view on Zotero

- ↑ Kenneth Hawkins, “The Therapeutic Landscape: Nature, Architecture, and Mind in Nineteenth-Century America” (PhD diss., University of Rochester, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, Reports of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane: for the years 1846–7–8–9 and 50 (Philadelphia: Published by order of the Board of Managers, 1851), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, “Description of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, with Remarks,” American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4 (April 1848): 347–54, view on Zotero.