William Hamilton

William Hamilton (April 29, 1745–June 5, 1813) was an accomplished amateur horticulturalist and botanist from Philadelphia. He was known especially for developing the English-style gardens at his estate, The Woodlands, during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

History

William Hamilton was a renowned amateur horticulturalist and botanist whose Schuylkill River estate, The Woodlands, was one of the premier examples of the English style of architecture and landscape design in the United States during the late 18th and early 19th centuries [Fig. 1]. He was born into a wealthy and prominent Philadelphia family, and, although he studied law at the College of Philadelphia, he never pursued a professional career.[1] Instead, as Catherine E. Kelly has noted, Hamilton “adopt[ed] the life of a leisured, landed gentleman”—an option made possible by his elite social position and family resources.[2] Hamilton treated “The Woodlands as his principle occupation,” according to Timothy Preston Long, spending a large share of his fortune “to perfect it as a work of art and to provide for himself a place for contemplation and scientific inquiry in agreeable retirement.”[3] One 1798 visitor to the estate reported that the proprietor was so consumed with The Woodlands that he seemed “interested only in his house, his hothouse and his Madeira” (view text).

Hamilton, who was a “confirmed loyalist and passionate Anglophile,” according to Kelly, looked toward English landscape theory and practice for models as he developed The Woodlands.[4] Soon after he came of age and took control of the property in the late 1760s, Hamilton began making significant changes to the grounds. He constructed a new mansion, enclosed 100 acres of land “to make a small park” (view text), and cut down “the Central Wood” in order to improve the view of Philadelphia from the estate (view text). However, Hamilton’s ambitions for The Woodlands grew during a nineteen-month trip to England from 1784–86.[5] While there, he toured regions of the countryside known for picturesque landscape gardens, such as Buckinghamshire, Wiltshire, Oxfordshire, and Herfordshire, and he soon began making plans for a major renovation of his own house and gardens.[6] He wrote to his personal secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith, that he desired to make the grounds at The Woodlands “smile in the same useful & beautiful manner” as the estates he had seen in England (view text), and he instructed Smith to send seeds from The Woodlands that he could trade for new specimens during his trip (view text). Hamilton also shipped from England “a number of curious Flowering Shrubs and Forest Trees to be transplanted” at The Woodlands (view text), thereby greatly increasing the botanical variety found in his garden.[7]

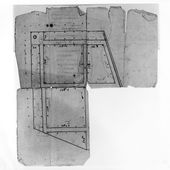

Upon his return to Philadelphia, Hamilton implemented plans for The Woodlands that integrated architectural and landscape design into a unified whole. He undertook a major renovation of his house, expanding and transforming it into a paragon of the latest English fashions, particularly the late-Georgian style associated with the architect Robert Adam (1728–1792). The house’s interior featured curvilinear forms and an Adamesque sense of movement that showcased views of Hamilton’s gardens and the surrounding landscape.[8] Although Hamilton almost certainly hired an English architect to assist with the plans for his mansion, he was in all likelihood, according to Aaron V. Wunsch, “the principal creative force behind the design of his grounds.”[9] Much of Hamilton’s correspondence reveals his extensive involvement in horticultural matters at The Woodlands as well as at the family’s other estate, Bush Hill. When he was away from home, Hamilton often voiced frustration that he did not receive more thorough updates about his plants and gardens from the team of caretakers he had hired to execute and maintain his vision; on June 12, 1790, for example, Hamilton chastised Smith, writing, “Common sense would point out the necessity of my having constant information respecting the grass grounds at Bush Hill and at The Woodlands which must be now nearly in a state for mowing. . . .” (view text). Hamilton imported hundreds of trees from England to supplement the native species already growing at the estate and constructed an enormous greenhouse flanked by two hothouses to cultivate his expanding collection of exotics.[10] By the early 19th century, Hamilton had amassed “between 7 & 8000 plants,” and his conservatory at The Woodlands was “said to be equal to any in Europe” (view text). He even took an active role in the design of more utilitarian features of his estate, sketching by hand a plan for the kitchen garden and orchard at The Woodlands [Fig. 2].

Hamilton maintained close relationships with leading botanists such as Humphry Marshall, David Hosack, the Bartrams, and François-André Michaux.[11] Despite significant political differences, shared interests in horticulture drew Hamilton into the social orbits of national leaders such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, with whom he exchanged seeds and plants and corresponded about matters of estate development.[12] Jefferson even selected Hamilton to be one of two recipients of rare seeds collected during the Lewis and Clark expedition—a testament to Hamilton’s reputation and level of expertise (view text).[13] While Hamilton was apparently generous in sending specimens to Washington and Jefferson, he appears to have been more protective of his plants with other collectors. Hamilton once chastised Smith for “not properly secur[ing] von Rohrs agave” because he had “wish’d to prevent its getting into other hands” (view text).[14]

Nonetheless, Hamilton earned a reputation for generosity because he readily welcomed visitors to The Woodlands to tour his house, gardens, and fine art collection.[15] Rev. Manasseh Cutler wrote after an 1803 trip to The Woodlands that Hamilton had spent the entire evening with his guests, poring over his collection of illustrated botanical books and comparing the drawings to real plants fetched from Hamilton’s greenhouse by his gardener (view text).[16] Hamilton also opened his plant collection for study by students training under Benjamin Smith Barton, Professor of Natural History and Botany at the University of Pennsylvania (view text). Contemporaries praised the “liberality” that Hamilton had “shown in [giving] free access to the house & grounds,” a supposedly selfless gesture that was declared “Non sibi sed aliis” [not for himself but for others] (view text).

—Lacey Baradel

Texts

- Hamilton, William, April 1779, in a letter to William Tilghman Jr. (quoted in Wunsch 2004: 23)[17] back up to History

- “I have just been making some considerable Improvements at the Woodlands, and I long to have you see them. . . . From the scarcity of Fence Nails, High prices and Difficulty of getting Labourers I have been obliged to throw 100 acres on the back of my House, into only one Enclosure which although not inconvenient has never [had a?] handsome Effect. You may recollect the Ground is Hill & Dale Woodland and plain and therefore well enough calculated to make a small park, and I am endeavoring to give it as much as possible a parkish Look. My Lawn too I expect will shine this summer, it already looks elegantly. And so it ought, you’ll say, when you are told the manuring it this last Winter has cost me £1500.”

- Hamilton, William, April 1779, in a letter to William Tilghman Jr. (quoted in Long 1991: 83)[18] back up to History

- “As to Philadelphia, I never go there without business calls me. Do you remember how anxious I was two or three years ago to have a peep at the Town, thro the Central Wood. ‘Twas then an object of my regard, but at present I do cordially hate it, that altho the prospect of it lately open’d by the total removal of the Wood is a most commanding one, & would at any other time have been admired, it is now absolutely disgusting to me. Judge by this what must be the Frame of my Mind.”

- Hamilton, William, April 1779, in a letter to William Tilghman Jr. (quoted in Long 1991: 84)[18]

- “The necessity I am under of repairing in some Degree, the Damage my Estate has sustained, gives me constant employment, & obliges me to stir about a good deal, and as it leaves less time for Thought, is I believe of considerable Service to my Health which I am persuaded would otherwise suffer, from my Reflexions on past and present Scenes.”

- Washington, George, January 15, 1784, in a letter from Mount Vernon to William Hamilton[19]

- “If I recollect right, I heard you say when I had the pleasure of seeing you in Philadelphia, that you were about a Floor composed of a Cement which was to answer the purpose of Flagstones or Tiles, and that you proposed to variegate the colour of the squares in the manner of the former.

- “As I have a long open Gallery in Front of my House to which I want to give a Stone, or some other kind of Floor which will stand the weather; I would thank you for information respecting the Success of your experiment—with such directions and observations (if you think the method will answer) as would enable me to execute my purpose. If any of the component parts are scarce & expensive, please to note it, & where they are to be obtained—& whether all seasons will do for the admixture of the Composition.

- “I will make no apology for the liberty I take by this request, as I persuade myself you will not think it much trouble to comply with it.”

- Hamilton, William, February 20, 1784, in a letter from Bush Hill to George Washington[20]

- “I engaged a person of the name of Turner, newly arrived from England, to do some stucco work at Bush Hill. While he was at the work I frequently talk’d with him about the different compositions now so much used in England particularly that for covering floors, Roofs, & fronts of Houses. He professed to understand the method of preparing & applying it & wished me to encourage him in giving a Specimen. To this, I at length consented, and he undertook to make a variegated floor in my Green House, one for an open portico on the front of my House on the Schuylkill, and to cover the flats of two Bow Windows. . . . I have enquired of Mr. Vaughan & several other english [sic] gentlemen who say great things of it.”

- Washington, George, April 6, 1784, in a letter from Mount Vernon to William Hamilton[21]

- “I have been favored with your letter of the 20th of Feb. & pray you to accept my thanks for the information contained in it.

- “I expect to be in Phila. the first of May, but if, in the meanwhile, you should be perfectly satisfied of the skill of Mr Turner and the efficiency of his work you would add to the favor already conferred on me by desiring him not to be engaged further than to yourself until I see him.

- “I have a large room which I intend to finish in Stucco & Plaister of Paris—besides this I have a Piazza in front of my House (open & exposed to the weather) of 100 feet by 12 or 14 which I want to give a Floor to of stone or a cement which will be proof against wet & frost——and I am, as you were, plagued with leaks at a Cupulo &ca which requires a skilful artist to stop. These, altogether, would afford Mr Turner a good job, whilst the proper execution of them would render me an acceptable Service.”

- Parke, Thomas, April 27, 1785, in a letter from Philadelphia to Humphry Marshall (quoted in Harshberger 1929: 278)[22] back up to History

- “W. Hamilton has sent a number of curious Flowering Shrubs & Forest Trees to be transplanted at his Seat on the Schuylkill.”

- Hamilton, William, September 24, 1785, in a letter from England to Dr. Thomas Parke (quoted in Betts 1979: 224–25)[23]

- “Having resolved on my return in the Spring I am daily looking forward to the arrangements for making my situation convenient and agreable. Some addition to the House, a stable & other offices are immediately necessary at the Woodlands, and as I have most severely felt the consequences of having workmen at extravagant prices, I mean to take from hence some who will engage with me for a certain number of years on moderate terms, & if the remittances will admit I will also purchase in this Country every kind of material by which any thing can be saved. Some indeed there are that will depend on taste, and as I am vain enough to like my own as well as that of any one, cannot be so well got by anybody else when my back is turn’d. In order to take time by the forelock, Mr. Bob Barclay has been so good as to write for me to Glasgow, & had order’d out two or three stone quarriers the expence of whose passages & c. will probably have to be paid by you. I know not yet the terms but will give you the earliest information. You will on their arrival fix them at the Woodlands & employ them during the winter at the quarry where the stones were raised for building the Bridge over the mill creek as I think that the best kind of stone. By the way I wish to have an experiment made with some of our stone & beg you will be so kind as to send me a block from that very quarry of about 12 Inches square & six Inches thick as also a block of the chester stone of the same size. You must be sensible too that I can get a first rate gardiner to go with me on very moderate terms compared with what that branch at present costs me & I shall not fail to suit myself.”

- Hamilton, William, September 30, 1785, in a letter from England to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Betts 1979: 225)[23] back up to History

- “Having observed with attention the nature, variety & extent of the plantations [in England] of shrubs trees & fruits & consequently admired them, I shall (if God grant me a safe return to my own country) endeavour to make it [the Woodlands] smile in the same useful & beautiful manner. To take time by the forelock, every preparation should immediately be made by Mr. Thompson who is on the spot, & I have no doubt you will assist him to the utmost of your power. The first thing to be set about is a good nursery for trees, shrubs, flowers, fruit, &c. of every kind. I do desire therefore that seeds in large quantities may be directly sown of the white flowering locus, the sweet or aromatic birch, the chestnut oak, horse chestnuts, chincapins. . . .”

- Hamilton, William, September 30, 1785, in a letter from England to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Smith and Hamilton 1905: 77)[24] back up to History

- “You have doubtless in the course of the summer collected many sorts of seeds, which you mean to send for the purpose of my exchanging them for others here. I enclose a list of such as are more particularly valuable & therefore the more of them that are sent the better. I have also named some plants that I shall be glad to obtain as being rare here. The violets I wish to have a large quantity of & if any of the particolor’d sort which I took from the field and planted in pots are yet in being, I must request that they be put up most carefully & sent to me. As I intend shipping another very large collection of plants shortly no time should be lost in preparing ground. If done this Fall the more like to be ready.”

- Hamilton, William, November 2, 1785, in a letter from England to Dr. Thomas Parke (quoted in Betts 1979: 225)[23]

- “As I can by no means afford to live in Bush Hill, I shall be under the necessity of adding to the House & building Offices at the Woodlands. Altho the state of my finances will not allow me to do much at present & the improvements must be gradual, It will be proper however to fix on some general plan for the whole & according as I have wherewithal while I am on the spot mean to procure whatever materials in the way of finishing & furnishing may be here purchased on a saving plan. The more I can do in this way the better as besides lessning the Expence There will be a great savings of time. I mention this to prove to you how very useful it will be to me for you to remit whatever Cash can be spared from my American occasions. I have the vanity to think I shall be thereby enable to introduce many conveniences & improvements that will be useful to my country as well as myself.”

- Hamilton, William, November 2, 1785, in a letter from England to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Hamilton and Smith 1905: 145)[25]

- “Besides these I must beg you to direct Mr Thomson to pack up the same number of plants of the like sorts & two or three dozen of the Double Tuberose roots & forward them to my address. The Roots should be put into dry sand & you should endeavor to have them kept in a dry part of the Ship. The plants must be packed in cases of Boxes with that kind of swamp moss that grows at the Head of the valley about the spot where the dwarf Laurels are (in the manner which Mr Young used to put up his plants of [which] Mrs Young will give you particular information. If my stock of Tuberose roots should have been from any accident exhausted you can be supplied by Jn° Slaughter who lived when I left home in a new House at the upper end of Arch St (the last next the common) where was a very large quantity of fine ones.”

- G., L., June 15, [1788?], in a letter to her sister Eliza (quoted in Betts 1979: 216–17)[23]

- “Mr. Hamilton was remarkably polite—he took us round his walks which are planted on each side with the most beautiful & curious flowers & shrubs. . . .”

- Hamilton, William, July 1788, in a letter from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Hamilton and Smith 1905: 150–51)[25]

- “I have personally play’d the Dun within these three or four days at more than 500 Houses & have applied for rents on unimproved lots, pastures & out lots. The people far from being displeased, are many of them flatter’d with what they call my condescension, & all approve the measure so unlike what they have been formerly used to. Not an uncivil word did I receive from any one, nor have I discovered one instance of a disinclination for payment, or an attempt at evasion. Scarcity of money is their only plea & there is surely every reason to believe it a just one. But although the poor of which there are a very great proportion can possibly never pay, they all acknowledge the justice of my claims & their wish to have the power to satisfy them. . . .”

- Hamilton, William, 1789, in a letter to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Madsen 1988: A4)[26]

- “In my Hurry at the time of coming off from Home I omitted to put in the ground the exotic Bulbous roots & as I gave no direction to Hilton respecting them they may suffer more especially as they were all taken out of the pots & left dry on the Back flue of the Hot House.”

- Hamilton, William, October 3, 1789, in a letter from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Hamilton and Smith 1905: 157–58)[25]

- “Mr Child told me he would not fail to remind you of getting McIlvee out to mend the hot house. Unless this is done the West India plants cannot be safe. . . . I think it will be well enough for you to go to Bartrams & know from him what Hot House plants he intended for me and also his prices for each of the plants in ye enclosed list. Its possible Mrs Rulen and her daughter will sail for the West Indies before my return. In case Miss Markoe comes to the Woodlands I wish Ann & Peggy would beg her to think of me in the flower seed way when she is at Santa Cruz. Those of all fragrant and beautiful plants will be agreeable, particularly ye Jasmines. . . .”

- Hamilton, William, June 12, 1790, in a letter from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Hamilton and Smith 1905: 258–59)[27] back up to History

- “Common sense would point out the necessity of my having constant information respecting the grass grounds at Bush Hill and at the Woodlands which must be now nearly in a state for mowing. . . . It would have been an agreeable circumstance to me to have heard the large sumachs & lombardy poplars as well as the magnolias have not been neglected. The immense number of seeds from foreign countries must certainly have produced (if attended to) many curious plants. The casheros, conocarpus Arnott’s walking plants &c which I planted out the day before I left home have I hope been taken care of. I should however been glad to have heard of their fate as well as respecting the Gooseberries and Antwerp Raspberries given me by Dr Parke. After the immense pains I took in removing the exotics to the north front of the House by way of experiment, & the Hurry of coming away preventing my arranging them, you will naturally suppose me anxious to know the success as to ye plants and the effect as to appearance in ye approach & also their security from cattle. The curious exotic cuttings & those of the Franklinea I did not believe it possible for even you to be inattentive to. . . . I wished you to be very active on the arrival of the India ships, in finding out whether any passengers had seeds &c . . . I find Bartram has Cape plants & seeds but hear not a word of your having got any for me. By the way, I should be glad if you had given the reason of Bartrams ill Humour when you called. He certainly had no cause for displeasure respecting his plants left under my care during the winter. . . Mr Wikoff promised me some seeds of a cucumber six feet long.”

- Hamilton, William, September 1790, in a letter from The Woodlands to his private secretary Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Hamilton and Smith 1905: 260)[27]

- “In case you go to Brannan’s I beg you to look particularly at his largest Gardenias & Arbutus so as to give an account of the size as well as the prices of them. I mentioned to you the Teucrium or Germander & I now recollect his having what he called a china rose. I have moreover a shrewd suspicion that Gray’s single Arabian Jasmine came from Brannans although Brannan may not know it by that name. You will therefore find out what Jasmines he has & their prices & see whether he has any aloes, Geraniums, myrtles &c which I have not. Possibly he may have another plant of the African Heath which Gray got from him & other large d'ble myrtles as good as Gray’s. You will also make the same enquiries of Spurry….

- “Brannan had a trefoil which he called a cinquefoil. I know not whether it has yet travelled to Grays. I take it to be the moon-trefoil? a very pretty shrub.”

- Hamilton, William, November 22, 1790, in a letter from The Woodlands to Humphry Marshall (Darlington 1849: 577)[28]

- “I was truly sorry that I did not see you when you were last at Philadelphia. I hope, the next time you come down, you will give me a call. If I can tempt you no other way, I promise to show you many plants that you have never yet seen, some of them curious.”

- Hamilton, William, June 6, 1791, in a letter from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Hamilton and Smith 1905: 261)[27]

- “The plants sent by Mr. Von Rohr are valuable & I hope George will particularly attend to them. The palm is called Cornon from Cayenne & along side of him as von Rohr says is a young cacao or chocolate plant. The last particularly is alive I hope. The Hibiscus tiliacens in ye 2d Box, is the mahoe tree, & the Roots are the pancratium maritimum. The flower pot contains an anacardium occidentale. As to the cereus cutting I would not have it divided but planted in a heavy pot of such a size as not to be over-potted & placed in such a situation as to be properly supported & secured from being blown over by the wind.”

- Hamilton, William, March 17, 1792, in a letter from The Woodlands to George Washington[29]</ref>

- “I will with great pleasure forward you on Monday whatever is in my power of the kinds of plants you desire & will prepare them in the best manner for the voyage.

- “The time being short, I am uncertain at what time of the day they may be ready. You need not therefore send for them. I will have them deliver’d at your House in the course of it.”

- Hamilton, William, August 13, 1792, in a letter from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to his private secretary Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Hamilton and Smith 1905: 264)[27] back up to History

- “It is a disappointment to me to find that you did not properly secure von Rohrs agave at Gray’s. I wish’d to prevent its getting into other hands. The same motive makes me desirous to have the Arbutus & the Rose apple which however are priced so high that I do not imagine they will find a ready sale before my return.”

- Hamilton, William, November 23, 1796, in a letter from The Woodlands to Humphry Marshall (Darlington 1849: 578)[28]

- “I am much obliged to you for the seeds you were so good as to send me, of the Pavia, and of the Podophyllum or Jeffersonia.

- “When you were last here it was so late, and you were of course so much hurried, as to prevent your deriving any satisfaction in viewing my exotics. I hope when you come next to Philadelphia, that you will allot one whole day, at least, for the Woodlands. It will not only give me real pleasure to have your company, but I am persuaded it will afford some amusement to yourself.

- “Your nephew [Moses Marshall] did me the favour of calling, the other day; but he, too, was in a hurry, and had little opportunity of satisfying his curiosity. I flatter myself, however, that during his short stay he saw enough to induce him to repeat his visit. The sooner this happens, the more agreeable it will be to me.

- “When I was at your house, a year ago, I observed several matters in the gardening way, different from any in my possession. Being desirous to make my collection as general as possible, I beg to know if you have, by layers, or any other mode, sufficiently increased any of the following kinds so as to be able, with convenience, to spare a plant of each of them, viz.: — Ledum palustre, Carolina Rhamnus, Azalea coccinea, Mimosa Intsia, and Laurus Borbonia. Any of them would be agreeable to me; as also would be a plant, or seeds Hippophae Canadensis, Aralia hispida, Spiraea nova from the western country; Tussilago Petasites, Polymnia tetragonotheca, Hydrophyllum Canadense, H. Virginicum, Polygala Senega, P. biflora, Napoea scabra dioica, Talinum, a nondescript Sedum from the west, somewhat like the Telephium, two kinds of a genus supposed, by Dr. MARSHALL, to be between Uvularia and Convallaria [probably the Streptopus, of MICHAUX, which the MARSHALLS proposed to call Bartonia], and Rubia Tinctorum. I should also be obliged to you for a few seeds of your Calycanthus, Spigelia Marilandica, Tormentil from Italy, and two of your Oaks with ovate entire leaves.”

- Hamilton, William, March 6, 1797, in a letter from The Woodlands to George Washington[30]

- “Having been told you intend leaving Town tomorrow I have sent the Clod of Grass, together with a plant of the upright Italian Myrtle & one of the Box leaved Myrtle for Mrs Washington. The plants will very safely bear the Journey as they are packed in the Basket, provided it is kept in an upright position out of the reach of Frost which would injure the Myrtles in their present growing State [.] a careful Gardener may separate the Clod of grass so as to make many plants of it. I am persuaded that in good soil & situation rather sheltered from the North West It would prove a valuable acquisition.

- “I lament exceedingly that I have been deprived of the pleasure of paying my respects in person previous to your Departure. I flatter myself however that you will take the will for the deed & believe that my best wishes for Health & every other Happiness will always attend Mrs Washington & yourself. I trust too that you will at all times when occasions offer command freely whatever is in my power You may be assured nothing can afford me more real satisfactn than an opportunity of serving you & that I am with sincere Regards Dear Sir your most devoted & very obedt Servant W. Hamilton

- “I have also sent half of the Seeds of the persian Grass saved last Season at the Woodl[an]ds.”

- Niemcewicz, Julian Ursyn, March 24, 1798, journal entry describing The Woodlands (1965: 52–53)[31] back up to History

- “On returning we saw the house of Hamilton. . . . Hamilton was not there. He is a man of 50 who in the time of the Revolution took the side of the English. He narrowly missed being hung for his fine loyalty. His farm contains 200 to 300 acres of very mediocre land as is all that in the environs of Philad, but which cultivated could produce something. He leaves it fallow; he is interested only in his house, his hothouse and his Madeira. He carries his fastidiousness about the countryside to such a point that he is in a dreadful humor when one comes to visit it during low tide.”

- da Costa Pereira Furtado de Mendonça, Hipólito José, February 24, 1799, in a diary entry describing The Woodlands (quoted in Smith 1954: 94–95)[32]

- “Today I dined with Mr. Hamilton, who lives on the other side of the Schuylkill. He is a learned man very much taken with the subject of botany. In his hothouse he has many plants from China and Brazil, including 15 species of the sensitive plant and many other kinds of mimosa. He had one variety of sugar cane that comes from an island in the Pacific and which is already being cultivated in the West Indies. It gives twice as much sugar as the regular plants and requires no more labor. He promised me seeds, etc., etc. I will make a catalogue of all the plants he has. He also has tea trees, jambo trees, guavas, etc.”

- da Costa Pereira Furtado de Mendonça, Hipólito José, March 6, 1799, in a diary entry describing The Woodlands (quoted in Smith 1954: 97)[32]

- “I went to Mr. Hamilton’s hothouse, where he awaited me with a catalogue of questions and then wrote down the answers as I gave them to him. . . .”

- da Costa Pereira Furtado de Mendonça, Hipólito José, March 26, 1799, in a diary entry describing The Woodlands (quoted in Smith 1954: 99)[32]

- “Today I saw in Mr. Hamilton’s hothouse two more varieties of mimosa, which I sketched.”

- da Costa Pereira Furtado de Mendonça, Hipólito José, March 26, 1799, in a diary entry describing The Woodlands (quoted in Smith 1954: 99)[32]

- “Today I dined with Mr. Hamilton, who sent me a precious collection of seeds. . . .”

- da Costa Pereira Furtado de Mendonça, Hipólito José, March 26, 1799, in a diary entry describing The Woodlands (quoted in Smith 1954: 105)[32]

- “Today I was at Mr. Hamilton’s and there I talked with Mr. Muhlenberg, a German who lives in Lancaster. He is the best botanist in the United States and a pastor in that area, but he was so crude and gross in his manners that I found him unbearable.”

- Hamilton, William, May 3, 1799, in a letter from The Woodlands to Humphry Marshall (Darlington 1849: 579–580)[28]

- “I have not until this time been able to comply with my promise of sending you a Tea Tree.

- “I now take the opportunity of forwarding you... a very healthy one, as well as several of other kinds, which I believe are not already in your collection; together with a small parcel of seeds. . . .

- “Should anything else, in my possession, occur to you as a desirable addition to the variety in your garden, I beg you will inform me. You may be assured, whatever it is, if I have two of the kind, you will be welcome to one. Sensible as I am of your kindness and friendship to me, on all occasions, you have a right, and may freely command every service in my power.

- “Doctor Parke informs me you were lately in Philadelphia. Had it been convenient to you to call at the Woodlands, I should have had great pleasure in seeing you. I have not heard of Dr. MARSHALL’S having been in this neighbourhood since I was last Bradford. From the pressing invitation I gave him, I am willing to hope that, in case of his coming to town, he will not forget to give me a call. I beg you will present him with my best respects, and request of him to give me a line of information, as to the Menziesia ferruginea, particularly of its vulgar name, if it has one, where it grows, if he knows the name of any person in its neighbourhood, who is acquainted with it, so, as to direct or show it to any one who may go to look after it.

- “I intend, next month, to go to Lancaster; and if convenient to me, when there, to spare my George, I have thoughts of sending him to Redstone, for the Menziesia, and Podophyllum diphiyllum. If Dr. MARSHALL knows of any curious and uncommon plants, growing in the neighbourhood with those I have mentioned, I will be obliged to him to give me any intelligence by which he may suppose they can be found: or, if he knows any person or persons at Redstone, or Fort Pitt, who are curious in plants, of whom any questions on the subject may be asked, he cannot do me a greater service than by giving me their names and place of abode.

- “I do not know how your garden may have fared during this truly long and severe winter, which has occasioned the loss of several valuable ones in mine; amongst which are the Wise Briar [probably Schrankia uncinata, Willd.; Mimosa Intsia, Walt.] and Hibiscus speciosus, which I got from you. The plants, also, of Podophyllum diphyllum, which I raised last year, from seeds I received from your kindness, have, I fear, been all destroyed. They have not shown themselves above ground this spring. A tree, too (the only one I had of Juglans Pacane, or Illinois Hickory), which I raised twenty-five years ago from seed, is entirely killed.

- “In case you have seeds of the kinds named in the list hereto adjoined, I will thank you exceedingly for a few. Any of them which you have not, at present, I beg you will oblige me with them in the ensuing fall. I am very desirous to know if your Iva, or Hog’s Fennel, from Carolina, produces seeds. In that case, I must entreat you for a few of them.

- “You will permit me, also, to remind you of your promise to spare me a plant or two of the White Persimmon, one of Azalea coccinea, and of the sour Calycanthus. If convenient to let me have a plant or two of your Stuartia Malachodendron, and of Magnolia acuminata, you will do me a great favour.

- “Anything left for me at the toll-gate, on the middle ferry wharf to the care of Mr. TRUEMAN, who constantly attends there, will reach me the same day that it arrives there. . . .

- “I am very desirous to compare a flower of your Stuartia with J. Bartram’s; and will be obliged to you for a good specimen.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, April 22, 1800, in a letter from Philadelphia to William Hamilton[33]

- “I am happy to find you as clear of political antipathies as I am: and am particularly obliged by the frankness of your explanation. I owe to it the opportunity of placing myself justly before you, and of assuring you there was no person here to whom I had less disposition of shewing neglect than to yourself. the circumstances of our early acquaintance I have ever felt as binding me in morality as well as in affection: and there are so many agreeable points in which we are in perfect unison, that I am at no loss to find a justification of my constant esteem.

- “Among the many botanical curiosities you were so good as to shew me the other day, I forgot to ask if you had the Dionaea muscipula, and whether it produces a seed with you. if it does, I should be very much disposed to trespass on your liberality so far as to ask a few seeds of that, as also of the Acacia Nilotica, or Farnesiana whichever you have.”

- Hosack, David, July 25, 1803, in a letter to Dr. Thomas Parke, regarding the greenhouses at the Elgin Botanic Garden and The Woodlands (Long 1991: 144)[34] back up to History

- “I duly received the plans of Mr. Hamiltons green and hot houses. My greenhouse [exclusive of the hothouses] is now finishing— it will not differ very individually from Mr. Hamiltons. . . . I hope William Hamilton will have duplicates of rare and valuable plants — I will supply him anything I possess.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, November 22, 1803, in a letter to his daughter Mrs. Torrey, describing The Woodlands (1888: 2:144–46)[35] back up to History

- “Since you are quite a gardener, I will mention a visit I made, on my journey, near Philadelphia, to a garden, which in many respects exceeds any in America. It is at the country-seat of Mr. Hamilton, a gentleman of excellent taste and great property. . . . As soon as we had dined, he [Mr. Pickering] called me aside, and told me he had been acquainted with Mr. Hamilton, who was noted for his hospitality, and who lived but half a mile up the river, where he did not doubt we should be kindly entertained. We immediately set out, and arrived about an hour before sunset. His seat is on an eminence, which forms on its summit an extended plain, at the junction of two large rivers.

- “Near the point of land a superb but ancient house built of stone is situated. In the front, which commends an extensive and most enchanting prospect, is a piazza, supported on large pillars, and furnished with chairs and sofas, like an elegant room. Here we found Mr. H., at his ease, smoking his cigar. He instantly recognized Mr. Pickering, and expressed much joy at seeing him. On Mr. Pickering introducing me, he took me by the hand with a pretty hard squeeze. 'Ah, Dr. Cutler, I am glad to see you at last. I have long felt disposed to be angry that I should hear of you so often at Philadelphia, and passing to and from the southward, and yet never make me a visit, and Dr. Muhlenburg, of Lancaster, a few days ago, made to me the same complaint. Come, gentlemen, walk in and take some refreshments, for I have much to show you, and it will directly be night.' This, and much more, was said as fast as he could utter it. . . . We then walked over the pleasure grounds in front and a little back of the house. . . .

- “. . . We retired to the house. The table was spread with decanters of different wines, and tea was served.

- “Immediately after, another table was loaded with large botanical books, containing most excellent drawings of plants, such as I never could have conceived. He is himself an excellent botanist. . . . When we turned to rare plants, one of the gardeners would be called, and sent with lanterns to the green-house to fetch me a specimen to compare with it. This was done perhaps twenty times.

- “Between 10 and 11 an elegant table was spread, with, I believe, not less than twenty covers. After supper, we turned again to the drawings, and at one we retired to bed. . . .”

- Hamilton, William, October 30, 1805, in a letter from The Woodlands to Thomas Jefferson[36]

- “On the strength of our long acquaintance I trust you will permit me the liberty I take of introducing to your notice, my nephew Andrew Hamilton, who intends passing a few days at the city of Washington & will have the pleasure of presenting you with this letter. He will at the same time, deliver to you a small deciduous plant of the silk tree of Constantinople (Mimosa salibrisin) which if well preserved for two or three years in a pot, will afterwards succeed in the open ground. I have trees of 20 feet height which for several years past have produced their beautiful & fragrand flowers & have shewn no marks whatever of suffering from the severity of the last winter.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, November 6, 1805, in a letter from Washington to William Hamilton[37]

- “Your nephew delivered safely to me the plant of the Chinese silk tree in perfect good order, and I shall nurse it with care until it shall be in a condition to be planted at Monticello. mr Madison mentioned to me your wish to recieve any seeds which should be sent me by Capt Lewis or from any other quarter of plants which are rare. I lately forwarded to mr Peale for the Philosophical society a box containing minerals & seeds from Capt Lewis, which I did not open, and I am persuaded the society will be pleased to dispose of them so well as into your hands. mr Peale would readily ask this. I happen to have two papers of seeds which Capt Lewis inclosed to me in a letter, and which I gladly consign over to you, as I shall any thing else which may fall into my hands & be worthy your acceptance. one of these is of the Mandan tobacco, a very singular species uncommonly weak & probably suitable for segars. the other had no ticket but I believe it is a plant used by the Indians with extraordinary success for Curing the bite of the rattle snake & other venomous animals. I send also some seeds of the Winter melon which I recieved from Malta. some were planted here the last season, but too early. they were so ripe before the time of gathering (before the first frost) that all rotted but one which is stil sound & firm & we hope will keep some time. experience alone will fix the time of planting them in our climate, so that a little before frost they may not be so ripe as to rot, & still ripe enough to advance after gathering in the process of maturation or mellowing as fruit does. I hope you will find it worthy a place in your kitchen garden.”

- Hamilton, William, July 7, 1806, in a letter from The Woodlands to Thomas Jefferson[38]

- “N.B. In the autumn I intend sending you if I live those kinds of trees which I think you will deem valuable additions to your garden viz. Gingko biloba or china maidenhair trees, Broussenatia papyrifesa vulgarly called paper mulberry tree & Mimosa abrisia or silk tree of Constantinople—The first is said by Kampfer to produce a good eatable nut—The 2d in its bark &c yields a valuable material for making paper to the inhabitants of China, Japan, & the East Indies, & for clothing to the people of Tahiti & other South Sea Islands & the third is a beautiful flowering tree at this time in its highest perfection, the seeds of which were collected on the shore of the Caspian Sea. They are all hardy having for several years past borne over severest weather in the open ground without th. smallest protection.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, July 31, 1806, in a letter to William Hamilton[39]

- “Your favor of the 7th came duly to hand and the plant you are so good as to propose to send me will be thankfully rec’d. The little Mimosa Julibrisin you were so kind as to send me the last year is flourishing. I obtained from a gardener in this nbh’d [neighborhood] 2 plants of the paper mulberry; but the parent plant being male, we are to expect no fruit from them,unless your [trees] should chance to be of the sex wanted. at a future day, say two years hence I shall ask from you some seeds of the Mimosa Farnesiana or Nilotica, of which you were kind enough before to furnish me some. but the plants have been lost during my absence from home. I remember seeing in your greenhouse a plant of a couple of feet height in a pot the fragrance of which (from it’s gummy bud if I recollect rightly) was peculiarly agreeable to me and you were so kind as to remark that it required only a greenhouse, and that you would furnish me one when I should be in a situation to preserve it. but it’s name has entirely escaped me & I cannot suppose you can recollect or conjecture in your vast collection what particular plant this might be. I must acquiese therefore in a privation which my own defect of memory has produced, unless indeed I could some of these days make an impromptu visit to Phila. & recognise it myself at the Woodlands. . . .

- “The grounds which I destine to improve in the style of the English gardens are in a form very difficult to be managed. They compose the northern quadrant of a mountain for about 2/3 of its height & then spread for the upper third over its whole crown. They contain about three hundred acres, washed at the foot for about a mile, by a river of the size of the Schuylkill. The hill is generally too steep for direct ascent, but we make level walks successively along it’s side, which in it’s upper part encircle the hill & intersect these again by others of easy ascent in various parts. They are chiefly still in their native woods, which are majestic, and very generally a close undergrowth, which I have not suffered to be touched, knowing how much easier it is to cut away than to fill up. The upper third is chiefly open, but to the South is covered with a dense thicket of Scotch (Spartium scoparium Lin.) which being favorably spread before the sun will admit of advantageous arrangement for winter enjoyment. You are sensible that this disposition of the ground takes from me the first beauty in gardening, the variety of hill & dale, & leaves me as an awkward substitute a few hanging hollows & ridges, this subject is so unique and at the same time refractory, that to make a disposition analogous to its character would require much more of the genius of the landscape painter & gardener than I pretend to. I had once hoped to get Parkins to go and give me some outlines, but I was disappointed. . . . Should a journey at any time promise improvement to it [Hamilton’s health], there is no one on which you would be received with more pleasure than at Monticello. Should I be there you will have an opportunity of indulging on a new field some of the taste which has made the Woodlands the only rival which I have known in America to what may be seen in England.

- “Thither without doubt we are to go for models in this art. Their sunless climate has permitted them to adopt what is certainly a beauty of the very first order in landscape. Their canvas is of open ground, variegated with clumps of trees distributed with taste. They need no more of wood than will serve to embrace a lawn or a glade. But under the beaming, constant and almost vertical sun of Virginia, shade is our Elysium. In the absence of this no beauty of the eye can be enjoyed. This organ must yield it’s gratification to that of the other senses; without the hope of any equivalent to the beauty relinquished. The only substitute I have been able to imagine is this. Let your ground be covered with trees of the loftiest stature. Trim up their bodies as high as the constitution & form of the tree will bear, but so as that their tops shall still unite & yeild dense shade. A wood, so open below, will have nearly the appearance of open grounds. Then, when in the open ground you would plant a clump of trees, place a thicket of shrubs presenting a hemisphere the crown of which shall distinctly show itself under the branches of the trees. This may be effected by a due selection & arrangement of the shrubs, & will I think offer a group not much inferior to that of trees. The thickets may be varied too by making some of them of evergreens altogether, our red cedar made to grow in a bush, evergreen privet, pyrocanthus, Kalmia, Scotch broom. Holly would be elegant but it does not grow in my part of the country.

- “Of prospect I have a rich profusion and offering itself at every point of the compass. Mountains distant & near, smooth & shaggy, single & in ridges, a little river hiding itself among the hills so as to shew in lagoons only, cultivated grounds under the eye and two small villages. To prevent a satiety of this is the principal difficulty. It may be successively offered, & in different portions through vistas, or which will be better, between thickets so disposed as to serve as vistas, with the advantage of shifting the scenes as you advance on your way.

- “You will be sensible by this time of the truth of my information that my views are turned so steadfastly homeward that the subject runs away with me whenever I get on it. I sat down to thank you for kindnesses received, & to bespeak permission to ask further contributions from your collection & I have written you a treatise on gardening generally, in which art lessons would come with more justice from you to me.”

- Drayton, Charles, November 2, 1806, describing The Woodlands (1806: 49, 55–57)[40] back up to History

- “Dined at Mr. Hamilton’s, at his elegant seat about 3 miles from Philadelphia. . . .

- “The Conservatory consists of a green house, & 2 hot houses—one being at each end of it. The green house may be about 50 feet long. The front only is glazed. Scaffolds are erected, one higher than another, on which the plants in pots or tubs are placed—so that it is representing the declivity of a mountain. At each end are step-ladders for the purpose of going on each stage to water the plants—& to a walk at the back-wall. On the floor a walk of 5 or 6 feet extends along the glazed wall & at each end a door opens into an Hot house—so that a long walk extends in one line along the stove walls of the houses & the glazed wall of the green house.

- “The Hot houses, they may extend in front, I suppose, 40 feet each. They have a wall heated by flues—& 3 glazed walls & a glazed roof each. In the center, a frame of wood is raised about 2 1/2 feet high, & occupying the whole area except leaving a passage along by the walls. In the flue wall, or adjoining, is a cistern for tropic aquatic plants. Within the frame, is composed a hot bed; into which the pots & tubs with plants, are plunged. This Conservatory is said to be equal to any in Europe. It contains between 7 & 8000 plants. To this, the Professor of botany is permitted to resort, with his Pupils occasionally.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, March 22, 1807, in a letter from Washington to William Hamilton[41] back up to History

- “It is with great pleasure that, at the request of Govenor Lewis, I send you the seeds now inclosed, being a part of the Botanical fruits of his journey across the continent: I cannot but hope that some of them will be found to add useful or agreeable varieties to what we now possess. these, with the descriptions of plants, which, not being in seed at the time, he could not bring, will add considerably to our Botanical possessions. he will equally add to the Natural history of our country. on the whole, the result confirms me in my first opinion that he was the fittest person in the world for such an expedition. he will be with you shortly at Philadelphia, where I have no doubt you will be so kind as to shew him those civilities which you so readily bestow on worth. I send a similar packet to mr McMahon, to take the chance of a double treatment. in confiding these public deposits to your & his hands, I am sure I make the best possible disposition of them.”

- Birch, William Russell, 1808, The Country Seats of the United States of North America (1808: unpaginated)[42]

- “This noble demesne has long been the pride of Pennsylvania. The beauties of nature and the rarities of art, not more than the hospitality of the owner, attract to it many visitors. It is charmingly situated on the winding Schuylkill and commands one of the most superb water scenes that can be imagined. The ground is laid out in good taste. There are a Hot house and green house containing a collection in the horticultural department, unequalled perhaps in the Unites States. Paintings &c. of the first master embellish the interior of the house and do credit to Mr. Wm. Hamilton, as a man of refined taste.” [Fig. 3]

- Hamilton, William, February 5, 1808, in a letter from The Woodlands to Thomas Jefferson[43]

- “Near thirty years ago, I passed some time at oxen-Hill opposite to Alexandria, in the month of february. at that season all the swamps that branch from oxen creek, were redden’d with the berries of what is there called, the winter haw, which grows not with us. I have since made several attempts to obtain plants from thence which have always been unsuccesful.

- “In the neighbourhood of Washington, there grows a tree Hazle, corylus arborescens, by which name, it is known to Doctr. Ott, of george town, who well knows it, & the place of its growth; as I have been informed.

- “Could I, do you think, by your assistance, obtain plants & seeds of one or both of these trees? I know very well how greatly your time is employ’d in more weighty concerns, & that you have scarcely enough of it, for such trifles, but I am persuaded you can in a few words, direct your gardener on the subject, & at the same time I am certain, that except yourself, there is not a man in Washington, that either can or will attend to matters of this kind. I flatter myself, that when you know how much you will oblige me by your attention to this business, you will not withhold it.

- “a little box (say a foot long & eight or ten inches wide) with a few holes, bored in its top, & sides, to allow a free circulation of air, & to prevent mould, will hold a sufficiency of plants. These should be young & not more than ten inches long. When taken from the ground, the earth should be shook well from them, & the bruised roots cut off. As soon as possible afterwards they should be placed in the box, between layers of swamp moss, (sphagnum palustre,) to keep them merely moist, & the roots from bruising each other, the box naild up on all sides, & if well done; they will, at this season of the year, bear a voyage to the West Indies. If some seeds are lightly scattered among the moss, they will be the better prepared for vegetation.

- “I have the pleasure to inform you that my green & hot houses are now in great perfection. Although my gardener is an indifferent one, he keeps them clean & neat as a parlour; & notwithstanding his want of knowledge, which occasions the loss of many plants, I am still rich in exotics of the most valuable kinds. I have still the camphire, the cinnamon, the clove, & the allspice as well as the tea & the coffee in high preservation. At this moment the coffee is full of fruit. Three or four sorts of sago & a dozen other palms thrive exceedingly. That most deliciois fruit, the india Mango, & what is nearly as fine the Cherimolia of Lima, the otaheite apple, the gooseberry of otaheite, the South sea plum, the guava, the water lemon, the china, & mandarin oranges, the citrons, the shaddock, the lemon, the lime &c &c &c all produce their fruits annually in succession.

- “Mr Lewis’s seeds have not yet vegetated freely, more however may come up this coming spring. I have nevertheless obtained plants of the yellow wood, or osage apple, seven or eight sorts of gooseberries & currants & one of his kinds of aricasara tobacco, have flower’d so well as to afford me an elegant drawing from it.

- “I have prepared for you plants of Broussenetis papysipra or paper Mulberry—Steroulia platamifolia (wrongly called china varnish Kew) & Mimosa Julibrisia or silk tree of constantinople all (with a little pains at first,) hardy enough to stand our climate. They were all design’d to come last year, but as suitable opportunity offerd I hope I will be more lucky this year.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, March 1, 1808, in a letter from Washington to William Hamilton[44]

- “I recieved in due time your friendly letter of Feb. 5. and was much gratified by the opportunity it gave me of being useful to you even on that small scale. I was retarded in the execution of your request by the necessity of riding myself to the only careful gardener on whom I have found I could rely, & who lives 3. miles out of town. it was several days before I could find leisure enough for such a ride. he has this day brought me a box, in which are packed the plants stated in the inclosed paper from him, that is to say 12. plants of what he calls the Winter berry (Prinus verticillatus) which he does not doubt to be the plant designated in your letter as the Winter haw. in fact the swamps in this neighborhood are now red with this berry. Dr. Ott however concieved another plant to be that you meant, and delivered the gardener some berries of it, which I now inclose you. should these berries be of the plant you meant, on your signifying it to me it may still be in time to procure and forward it to you. apprehending myself that neither of these plants might be the one you wished, but a real haw, now full of beautiful scarlet berries, and which I have never seen but in this neighborhood, I directed mr Maine (the gardener I mentioned) to put half a hundred of them into the box. even should they not be what you had in view still you should know this plant, which is peculiar at least to America & is a real Treasure. as a thorn for hedges nothing has ever been seen comparable to it. certainly no thorn in England which I have ever seen makes a hedge any more to be compared to this than a log hut to a wall of freestone. if you will plant these 6. I. apart you will be a judge of their superiority soon. he has put into the box 8. plants of the tree hazle you desired, taken from the very spot from which Dr. Ott had formerly got them for Doct. Muhlenberg. you will find a nut from them in the top of the box. these were all the small plants which he could get with any roots. to these I have added 9. plants of the Aspen from Monticello which I formerly mentioned & promised to you. it is a very sensible variety from any other I have ever seen in this country, superior in the straitness & paper whiteness of the body; & the leaf is longer in it’s stem, consequently more tremulous, and it is smooth (not downy) on it’s under side. this box goes in the stage of this evening under the immediate care of mr Soderstrom’s servant.

- “I am very thankful to you for thinking of me in the destination of some of your fine collection. within one year from this time I shall be retired to occupations of my own choice, among which the farm & garden will be conspicuous parts. my green house is only a piazza adjoining my study, because I mean it for nothing more than some oranges, Mimosa Farnesiane & a very few things of that kind. I remember to have been much taken with a plant in your green house, extremely odoriferous, and not large, perhaps 12. or 16. I. high if I recollect rightly. you said you would furnish me a plant or two of it when I should signify that I was ready for them. perhaps you may remember it from this circumstance, tho’ I have forgot the name. this I would ask for the next spring if we can find out what it was, and some seeds of the Mimosa Farnesiena or Nilotica. the Mimosa Julibrisin or silk tree you were so kind as to send me is now safe here, about 15. I. high. I shall carry it carefully to Monticello. I will not trouble you for the paper Mulberry mr Maine having supplied me with 12. or 15. which are now growing at Monticello. your collection is really a noble one, & in making & attending to it you have deserved well of your country. when I become a man of leisure I may be troublesome to you. perhaps curiosity or health may lead you into the neighborhood of Monticello some day, where I should be very happy to recieve you & be instructed by you how to overcome some of it’s difficulties. I salute you with great friendship & respect.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, July 14, 1808, in a letter to Monsieur de la Cépèd (1944: 373)[45]

- “In the meantime, the plants of which he [Governor Lewis] brought seeds, have been very successfully raised in the botanical garden of Mr. Hamilton of the Woodlands, and by Mr. McMahon, a gardener of Philadelphia.”

- M'Mahon, Bernard, January 3, 1809, letter from Philadelphia to Thomas Jefferson (quoted in Long 1991: 149)[46]

- “I have from time to time given Mr. Hamilton a great variety of plants, and altho’ he is in every respect a particular friend of mine, he never offered me one in return; and I did not think it prudent to ask him, lest it should terminate that friendship; as I well know his jealousy of any person’s attempt to vie with him, in a collection of plants.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, May 7, 1809, in a letter from Monticello to William Hamilton[47] back up to History

- “I have a grandson, Thos J. Randolph, now at Philadelphia, attending the Botanical lectures of Doctr Barton, and who will continue there only until the end of the present course. altho’ I know that your goodness has indulged Dr Barton with permission to avail himself of your collection of plants for the purpose of instructing his pupils, yet as my grandson has a peculiar fondness for that branch of the knolege of nature, & would wish, in vacant hours to pursue it alone, I am led to ask for him a permission of occasional entrance into your gardens, under such restrictions as you may think proper. I have so much experience of his entire discretion as to be able with confidence to assure you that nothing will recieve injury from his hands. I have desired him to deliver this to you himself, as well for the honor of personally presenting his respects to you, as of giving you assurances of the discreet use he will make of your indulgence. I have pressed upon him also to study well the style of your pleasure grounds, as the chastest model of gardening which I have ever seen out of England.”

- Martin, William Dickinson, May 20, 1809, journal entry describing The Woodlands (1959: 34–36)[48] back up to History

- “To the honour of the tasteful proprietor of this place it must be observed, that to him, we are indebted for having brought into this country, the Lombardy poplar, now so usefully ornamental to our cities, as well as our villas. To him we likewise owe the introduction of many other foreign trees, which now adorn our grounds, such as the Sycamore, the witch elm, the Tartarian Maple etc., etc. Altho’ much has been done to beautify this delightful seat, much still remains to be done, for the perfecting it in all the capabilities which nature in her boundless profusion has bestowed. These improvements it is said, fill up the leisure moments, & form the most agreeable occupation of its possessor: and that he may long live to pursue this refined pleasure, must be the wish of the public at large, for to them, so much liberality has even been shown in the free access to the house & grounds, that of the enjoyment of the fruits of his care, & cultivated taste, it may be said truly, Non sibi sed aliis.”

- Obituary for William Hamilton, June 8, 1813 (Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser: 3)[49]

- “His noble mansion was for many years the resort of a very numerous circle of friends and acquaintances, attracted by the affability of his manners, and a frankness of hospitality, peculiar to himself, which made even strangers feel at once welcome, easy and happy in his society.

- “Mr. Hamilton was distinguished for good taste and judgment in the Fine Arts, as well as for a very general knowledge of botany.—The study of botany was the principal amusement of his life.—He was engaged in extensive correspondence with persons of celebrity in the same pursuit, in distant countries, as well as in the United States, and in an interchange with them of whatever was rare, or useful in that part of natural history.”

Images

William Hamilton, Plan for Kitchen Garden and Orchard, June 1790.

James Peller Malcolm, The Woodlands From the Bridge at Gray’s Ferry, c. 1792–94, in Beth C. Wees and Medill H. Harvey, Early American Silver in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (2013), 259.

William Groombridge, The Woodlands, the Seat of William Hamilton, Esq., 1793.

Charles Drayton I, Sketch of The Woodlands, Seat of William Hamilton, in the Diary of Charles Drayton I, 1806.

William Russell Birch, “Woodlands, the Seat of Mr. Wm. Hamilton, Pennsylva.,” 1808, in William Russell Birch and Emily Cooperman, The Country Seats of the United States (2009), 69, pl. 14.

Pavel Petrovich Svinin, View of Morrisville, General Moreau’s Country House in Pennsylvania, Possibly The Woodlands, Pennsylvania, c. 1811—13.

William Strickland, “The Woodlands,” 1809, in The Casket 5 (Oct. 1830): 432.

Other Resources

The Woodlands Official Website

Library of Congress Authority File

Notes

- ↑ Hamilton was the grandson of the famous colonial lawyer and politician Andrew Hamilton (1676?–1741), who is best known for successfully defending the freedom of the press in the 1735 trial of the New York printer John Peter Zenger. Aaron V. Wunsch, Woodlands Cemetery, Historic American Landscapes Survey PA-5 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2004), 8, view on Zotero; Richard J. Betts, “The Woodlands,” Winterthur Portfolio 14, no. 3 (Autumn 1979): 221, 223–24, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hamilton earned income by leasing land he had inherited from his father and his uncle, James Hamilton (1715?–1783); see Catherine E. Kelly, Republic of Taste: Art, Politics, and Everyday Life in Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 122, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Preston Long, “The Woodlands: A ‘Matchless Place,’” (master’s thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 1991), 68, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kelly 2016, 120. For a discussion of Hamilton’s politics, especially during and immediately after the American Revolution, see also pages 125–30, view on Zotero.

- ↑ In 1784, the year after the American Revolutionary War ended, Hamilton traveled to England to settle financial matters related to the estate of his recently deceased uncle, James Hamilton (1715?–1783). Although loyal to the Crown, the Hamiltons had managed to survive the Revolution with their property holdings intact, but their finances—like those of most elite families in Philadelphia—were in a state of complete disorder. James A. Jacobs, The Woodlands (Revised Documentation), Historic American Buildings Survey PA-1125 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service), 50, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Wunsch 2004, 8, view on Zotero; Betts 1979, 225–26, view on Zotero. As Wunsch and Elizabeth Milroy have argued, Hamilton’s plans for The Woodlands reveal the proprietor’s familiarity with principles advanced by some of the leading theorists and practitioners of English landscape and garden design during the period, including Lancelot “Capability” Brown (1716–1783), Thomas Whately (1726–1772), and the nurseryman Nathaniel Swinden (active c. 1768–1805). Wunsch 2004, 1, 8–10 view on Zotero; Elizabeth Milroy, The Grid and the River: Philadelphia’s Green Places, 1682–1876 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016), 130, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Wunsch 2004, 25, view on Zotero. Hamilton is credited with introducing many plants species to North America, especially the ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba), the Lombardy poplar (Populus nigra ‘Italica’), the ailanthus (Ailanthus altissima), and the Norway maple (Acer platanoides). Karen Madsen, “To Make His Country Smile: William Hamilton’s Woodlands,” Arnoldia 49, no. 2 (Spring 1989): 21, view on Zotero.

- ↑ The use of mirrors hung on the interior doors and window shades enhanced this effect by reflecting views of the landscape throughout the home. Kelly 2016, 133–37 view on Zotero; Long 1991, 56–62, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Wunsch 2004, 10, view on Zotero. Although the identity of Hamilton’s architect remains unknown, Betts has argued that the architect was probably someone emulating the style of Robert Adam or John Soane. Betts 1979, 226, view on Zotero. More recently, Long and Jacobs have suggested that Hamilton may have consulted with the architect John Plaw (1745?–1820). Long 1991, 101–3, view on Zotero; Jacobs, The Woodlands (Revised Documentation), 5–6, view on Zotero. Jacobs also speculates that Hamilton may have designed the house himself, perhaps drawing inspiration from Wrotham Park in Herfordshire. See pages 7–8.

- ↑ Kelly 2016, 132–33, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lisa L. Ford, “A World of Uses: Philadelphia’s Contributions to Useful Knowledge in François-André Michaux’s North American Sylva,” in Knowing Nature: Art and Science in Philadelphia, 1740–1840, ed. Amy R. W. Meyers (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011), 293, view on Zotero; Thomas J. Schlereth, “Early North American Arboreta,” Garden History 35 (2007): 199, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kelly 2016, 141–42. During the American Revolution, Hamilton was arrested twice (once in 1778 and again in 1779). Following the first arrest, Hamilton was tried and acquitted of high treason. After his second arrest, Hamilton served a brief prison sentence and paid a large fine but was eventually allowed to return home and remain in Pennsylvania for the duration of the conflict. See pages 124–25, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hamilton and Jefferson were both members of the American Philosophical Society, to which Hamilton had been elected a member on July 27, 1797. Long 1991, 156, view on Zotero.

- ↑ See also Therese O’Malley, “Cultivated Lives, Cultivated Spaces: The Scientific Garden in Philadelphia, 1740–1840,” in Meyers 2011, 48, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For a description of Hamilton’s art collection, see Jacobs, The Woodlands (Revised Documentation), 68–70, view on Zotero; Oliver Oldschool [Joseph Dennie], “American Scenery—for the Port Folio. The Woodlands,” The Port Folio 2, no. 6 (December 1809), 505–7 view on Zotero.

- ↑ By the mid-1780s Hamilton’s library included sixty-one books on botany alone. Wunsch 2004, 85, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Wunsch 2004, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Letter from William Hamilton to William Tilghman Jr., Society Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, quoted in Long 1991, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Washington Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ George Washington, The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, ed. William Wright Abbot and Dorothy Twohig, 6 vols (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1992), 1: 135&nadsh;36, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Washington Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ John W. Harshberger, “Additional Letters of Humphry Marshall, Botanist and Nurseryman,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 53 (1929), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Betts 1979, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin H. Smith and William Hamilton,”Some Letters from William Hamilton, of the Woodlands, to His Private Secretary,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 29, no. 1 (1905), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 William Hamilton and Benjamin H. Smith, “Some Letters from William Hamilton, of the Woodlands, to His Private Secretary (Continued),” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 29, no. 2 (1905), view on Zotero.

- ↑ “William Hamilton’s Woodlands.” Paper presented for seminar in American Landscape, 1790–1900, instructed by E. McPeck. Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University. 1988, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 William Hamilton and Benjamin H. Smith,”Some Letters from William Hamilton, of the Woodlands, to His Private Secretary (Concluded),” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 29, no. 3 (1905), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 William Darlington, Memorials of John Bartram and Humphry Marshall: With Notices of Their Botanical Contemporaries (Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Washington Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Washington Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, Under Their Vine and Fig Tree: Travels through America in 1797–99, 1805, with Some Further Account of Life in New Jersey, ed. and trans. Metchie J. E. Budka, Collections of The New Jersey Historical Society at Newark (Elizabeth, NJ: The Grassmann Publishing Company, 1965), xiv, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 Robert C. Smith, “A Portuguese Naturalist in Philadelphia, 1799,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 78, no. 1 (January 1954), view on Zotero

- ↑ Jefferson Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Ms. letter in Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection, Boston Public Library, quoted in Long 1991, view on Zotero; and Christine Chapman Robbins, David Hosack: Citizen of New York (Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 1964), 65, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Masnasseh Cutler, Life, Journals and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D., ed. William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkin Cutler, 2 vols. (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co, 1888), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jefferson Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Jefferson Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Jefferson Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Jefferson Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Charles Drayton, “The Diary of Charles Drayton I, 1806,” 1806, Drayton Hall: A National Historic Trust Site, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jefferson Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ William Russell Birch, The Country Seats of the United States, ed. Emily Cooperman (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 68, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jefferson Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Jefferson Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Letter from Bernard M'Mahon to Thomas Jefferson, Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress, quoted in Long 1991, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jefferson Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ William D. Martin, The Journal of William D. Martin: A Journey from South Carolina to Connecticut in the Year 1809, ed. Anna D. Elmore (Charlotte, NC: Heritage House, 1959), view on Zotero. This passage is reprinted in Oldschool 1809, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Obituary for William Hamilton, Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser 42, no. 11402 (June 8, 1813), view on Zotero.