Veranda

(Verandah)

History

Several words were used synonymously to describe covered walks or spaces supported by columns or piers and attached to, or to part of, a building. This architectural feature spoke to the interrelatedness of architecture and gardens, a relationship that grew out of the romantic interest in landscape characterizing the aesthetics of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

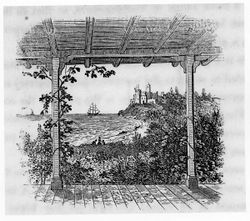

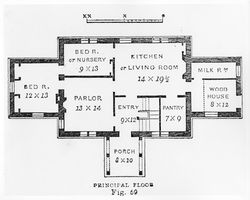

Two images exemplify the importance of the piazza, veranda, porch, and portico in creating and framing views of the garden and landscape. The first is a drawing of York Island, Long Island, by William Russell Birch (1808), who explained that the view was taken from the piazza, a place from which one could see "innumerable seats, spreading over an extensive country which glittered as the sun arose" [Fig. 1].[1] The second is from A. J. Downing's book on wooden picturesque houses, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850) [Fig. 2]. Both illustrated views from the bracketed piazza, or veranda, as Downing preferred to call it, out to the distant prospect.

Various treatises used all of these terms interchangeably in their definitions. Alexander Jackson Davis and Downing also used the term 'umbrage' to refer to the same feature on a house, implying a place of shade.[2] Mary Elizabeth Latrobe mentioned that in New Orleans the piazza was known as the gallery.[3] Contrasting usage of these words sometimes could offer distinctions. Rev. Manasseh Cutler, for example, in his description of Monticello, said that the term "portico" refers to smaller entrance porches and the term "piazza" to extended covered walkways stretching perpendicularly from the porticos. For the purposes of this essay, each of the four key terms will be described in turn, highlighting any specific meanings that have been attributed to them.

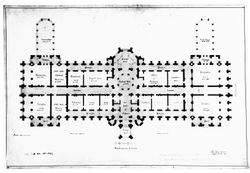

In 1828, Frances Milton Trollope, the acerbic critic of American art and architecture, described the piazza as a "luxury almost universal in the country houses of America." Indeed it was a feature found throughout the colonies and dates from the late eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries. From Massachusetts to the lower Mississippi Valley, examples are found on both private and public buildings. The feature was adapted to various styles with appropriate detailing and ornamentation. The piazza was a projecting porch or connecting passage that was identifiable in neoclassical plantation houses in the South, as well as in the Gothic revival suburban cottages of New Jersey and Pennsylvania. There were countless variations ranging from the simple wooden post-and-lintel type, to stone-arched piazzas depicted by Batty Langley [Fig. 3] and mentioned in 1839 at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.

In texts and images related to American gardens of the period under study, although several imported treatises traced "piazza" back to covered walkways that surrounded the square, the term has not been associated with the Italian term for a medieval or renaissance square. It was generally described as two related but somewhat distinctive appendages to buildings. First, the piazza was attached porch-like to a façade so that three sides of the piazza projected out from the building [Fig. 4], or the sides were recessed into the structure, as on the main façade of the U.S. Naval Asylum in Philadelphia [Fig. 5]. At other times it appeared on more than one façade [Fig. 6]. In New Orleans one house was described as having piazzas on all four sides. Both one- and two-story piazzas were also built. Second, "piazza" also referred to a covered walkway embedded between two buildings and acting as a connecting link. A single- or even double-height piazza, such as that described in 1799 on a property in Richmond, Va., provided either an entrance or transition space from interior architecture to exterior space. In the case of the University of Virginia, piazzas linked the entire range of houses around the lawn, and they served as transitional spaces leading to the lawn [Fig. 7].

The piazza's basic structure consisted of a roof supported by pillars or columns. A piazza might be walled on each side with Venetian blinds or, as Harriet Martineau described one in 1835, "draperied with vines." Flooring was stone, flag, wooden planks, or gravel. The roof was generally either flat or peaked. James E. Teschemacher (1835), however, described and illustrated a piazza with a concave roof formed of painted floor cloth fastened on wooden rafters, which were supported by wooden arches. Several images depict the piazza at ground level opening directly out into the landscape. Some examples, however, describe broad and spacious flights of stairs leading from the piazza and 'descending into the garden.' At Thomas Jefferson's Monticello (Charlottesville) and Poplar Forest (Bedford County, Va.), the piazzas had no immediate access to the ground but instead were raised, balcony-like structures overlooking the garden. Even if not a physical link, the visual connection to the exterior remained critical to the function of this feature.

The nineteenth-century architect William H. Ranlett, who used them often in his residential design, praised piazzas for their "very expressive" purpose.(view text) They functioned as sitting areas that were furnished with couches, chairs, and sometimes tables where one could take a meal. They were used to provide a place for walking or sitting and enjoying the breeze, shade and coolness; they also served to keep the sun from warming the interior of the house. Since the feature was designed to provide views in addition to protection from the sun, orientation of the piazza had to be planned with regard to the sun and surrounding environment. At Hyde Park, a visitor in 1830 mentioned that one piazza was open to the Hudson River and the other looked over a beautiful lawn, suggesting that the view dictated where the piazzas might be located.

Ranlett was emphatic when he decreed that a "dwelling should always have one or more of them [piazzas]." He regarded the absence of a piazza on a new house an indication of ignorance, niggardliness, and narrow- minded views. Downing (1850) went so far as to proclaim the lack of a piazza or veranda in any but the most utilitarian structure as "unphilosophical and false in taste!" He claimed that it was a resting place, lounging spot, and place of social resort of the whole family across nearly the entire extent of the United States () [Fig. 8].

Appearing only in the mid-nineteenth century in treatise literature with any frequency, the term "veranda" (also spelled verandah) was used in 1748 in Pehr Kalm's Travels in North America, in which he described small balconies or porches on houses.[4] Many visual and textual examples indicate that veranda served as an intermediary space between a house and its garden. Downing described it as an overhanging or low roof supported by an open colonnade or framework. He recommended that it have a gravel or wooden surface rising six to eight inches above the surrounding ground.() Climbing plants often covered verandas. Some writers refer to arbor-verandas and also mention the latticework that provided screening and support for climbing plants. Ornamental brackets and bargeboards also added to the decorations of the veranda.

The term was, as mentioned, often used interchangeably with "porch," "portico," and "piazza." Ranlett sometimes distinguished between the two, using "piazza" for a projecting roof and "veranda" for an overhanging roof(). Downing used the term "porch" to identify that part of the veranda where steps led from the ground to the entryway. He also used the term "pavilion" synonymously with "veranda".

Downing (1850) expounded at length on the meaning of the veranda, which he saw as a truly American feature not found in European architecture ().[5] Always concerned with identifying a national style, he believed that the veranda, in addition to providing shade and transitional zone from house to garden, was not simply ornamental but useful and "connected with the life of the owner of the cottage." Its presence expressed the ownership of a family exhibiting rural taste and a love of [picturesque] character, a family "at home in the country."

Although the veranda was an architectural feature found in the colonial and early national periods, it became a key component of asymmetrical picturesque design for both landscape and architecture in the 1840s.[6] Many illustrations for house pattern books by Downing and his followers depicted plans and elevations in various romantic styles that feature the veranda as an element in a new spatial organization that experimented with the interweaving of interior and exterior space. In his Treatise (1849) Downing wrote, "architectural beauty must be considered conjointly with the beauty of the landscape or situation," and "if properly designed and constructed . . . will even serve to impress a character on the surrounding landscape."[7] That the frontispiece to his Treatise illustrated the veranda at Blithewood underscores the importance of this theoretical stance. Another drawing of Blithewood [Fig. 9] by Alexander Jackson Davis presented, from the house and through the semi-enclosed space of the veranda, the view of the landscape toward the river, exemplifying the interpenetration of space that became for Davis and Downing an important characteristic of their architecture. Architectural historians have written about the veranda as a major component in picturesque architecture and a mark of distinction between American and English houses of the Gothic revival.[8]

The term "porch," as the 1828 dictionary entry by Noah Webster indicates, refers to a roofed architectural element often supported by columns or piers, either attached to a building or existing as an independent garden structure. During the colonial and early Republic periods three kinds of porches were evident throughout America. First, the porch was either an open or enclosed projecting roofed area of a building that sheltered a doorway or entrance [Fig. 10]. Since most gardens were situated next to the house, a porch was often a point of access from the house to the ornamental grounds. Eliza Caroline Burgwin Clitherall (active 1801) depicted such a porch at the Hermitage in Wilmington, N.C. [Fig. 11].

The second meaning of the term referred to a covered sitting and viewing area that was either attached to the building or was free-standing. In describing the use of porches as "decorative marks to the entrances of scenes" (akin to those of a theater proscenium), J. C. Loudon was referring to their use as embellished shelters over benches or seats placed in the garden. Downing's description of the rustic porch at Montgomery Place, on the Hudson River in Dutchess County, N.Y., argues that in addition to punctuating or shaping garden scenery, as Loudon recommended, porches, if appropriately placed and decorated, offered a way to situate a seat in the landscape thereby directing a view or prospect [Fig. 12]. Its function also allowed those seated to observe the landscape in all kinds of weather, as described in 1749 by Pehr Kalm. Downing's porches make clear the function of the porch as a mediator between interior and exterior realms. He praised porches that were covered with vegetation for easing the transition from outside to inside, and for providing evidence of the cultivated domesticity within the home [Fig. 13].

The third kind of porch is described by Downing as the carriage porch, or porte cochère, where in a grand home the arriving guests drew up under an architectural canopy for shelter. John Notman similarly inscribed the term porte cochère on his unexecuted design for the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. [Fig. 14]. He includes porches for the side entrances and piazzas for galleries running along the façades.

The term "portico" was also used when referring to a covered space that was supported by columns or piers and was attached to a building. Semantic distinctions were made, however, using "portico" to identify the principal entrances to the house and "piazza" for the extended side porches. The higher status of the portico, as opposed to piazza, veranda, or porch, was emphasized by its frequent modification by adjectives such as "handsome," "noble," and "elegant" [Fig. 15]. The word "portico" seems not to have been used to refer to covered walkways that linked separate buildings, as is made clear in the distinction in 1777 regarding the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Va.

Margaret Bayard Smith in 1828 said the portico at President James Madison's plantation, Montpelier, commanded a view, "a beautiful scene," of extensive lawns and forests, where viewers walked through the portico until twilight when the landscape was no longer visible [Fig. 16]. John Mason recalled the portico at George Mason's Gunston Hall, near Mason Neck, Va., from which "you descended directly into an extensive garden."(view text) Downing's 1849 comments conveyed a similar meaning, suggesting that the portico served to connect the building, visually and also physically, "by gradual transition with the ground about it."

The portico served as a focal, as well as a viewing, point. Lewis Miller, for example, in 1849 wrote that at Mount Vernon the "lofty portico . . . has a pleasing effect when viewed from the water" [Fig. 17]. Often the portico was distinguished from the building it ornamented by its material, creating a distant focus for the spectator from the garden or surrounding landscape. A brick building was sometimes ornamented with a contrasting white stone or painted wood portico. As David Bailie Warden noted in 1816, such a feature made a house "admirably adapted to the American climate."

Porticos generally were dressed in a classical style, meaning that classical columns supported the low-pitched roof and the front was finished with an entablature and pediment. Many descriptions specified Doric (e.g., Centre Square in Philadelphia), Tuscan (e.g., the Woodlands near Philadelphia), or Corinthian (e.g., Ranlett's design for a house in Italian bracketed style). Two notable exceptions to the classical style, however, are well known. William Buckland's fanciful octagonal porch at Gunston Hall (1755-58) had ogee arches and is thought to have been inspired by the writings of Batty Langley, who promoted Gothic and chinoiserie details for architectural decoration [Fig. 18]. Benjamin Henry Latrobe's Gothic design for Sedgeley, near Philadelphia (1799) [Fig. 19], which is considered one of the earliest Gothic revival houses in America, had tall slender posts supporting the roof.

Thus, two points are important in the history of these terms: First, these architectural elements served to elide the boundaries of the garden and building by linking interior and exterior space both visually and physically. Second, the associative values of refinement and domesticity, and even national progress, were read into the forms. --Therese O'Malley

Texts

Usage

- Kalm, Pehr, October 29, 1748, describing New Brunswick, N.J. (1937: 1:121)[9]

- "The houses are covered with shingles. Before each door is a veranda to which you ascend by steps from the street; it resembles a small balcony, and has benches on both sides on which the people sit in the evening to enjoy the fresh air and to watch the passers-by."

- Lambert, John, 1816, describing Charleston, S.C. (2:125)[10]

- "Almost every house is furnished with balconies and verandas, some of which occupy the whole side of the building from top to bottom, having a gallery for each floor."

- Hall, Capt. Basil, 1828, describing a plantation he visited during his trip from Charleston, S.C., to Savannah, Ga. (quoted in Jones 1957: 98)[11]

- "From the drawing-room, we could walk into a verandah or piazza, from which, by a flight of steps, we found our way into a flower garden and shrubbery."

- Hall, Capt. Basil, 1828, describing Alabama (quoted in Lockwood 1934: 2:389)[12]

- "We soon left our comfortless abode [the inn] for as neat and trig [sic] a little villa as ever was seen in or out of the Tropics. This mansion, which in India would be called a Bungalow, was surrounded by white railings, within which lay an ornamental garden, intersected by gravel walks, almost too thickly shaded by orange hedges, all in flower. From the light airy verandah, we might look upon the Bay of Mobile. . . .Many similar houses nearly as picturesque as our own delightful habitation, speckled the landscape in the south and east, in rich keeping with the luxuriant foliage of that evergreen latitude."

- Ingraham, Joseph Holt, 1835, describing a sugar plantation near New Orleans, La. (1:80-81)

- "The house was quadrangular . . . [and] was built of wood, painted white, with Venetian blinds, and latticed verandas, supported by slender and graceful pillars, running round every side of the dwelling. . . . At each extremity of the piazza was a broad and spacious flight of steps, descending into the garden which enclosed the dwelling on every side."

- Lyell, Sir Charles, December 23, 1845, describing Charleston, S.C. (1849: 1:229)[13]

- "Almost all the best houses in Charleston are built with verandahs, and surrounded with gardens."

- Lyell, Sir Charles, December 28, 1845, describing Beaufort, S.C. (1849: 1:231)[13]

- "we approached Beaufort, a picturesque town composed of an assemblage of villas, the summer residences of numerous planters, who retire here during the hot season, when the interior of South Carolina is unhealthy for the whites. Each villa is shaded by a verandah, surrounded by beautiful live oaks and orange trees laden with fruit."

- Earle, Pliny, January 1848, describing Bloomingdale Asylum for the Insane, New York, N.Y. (Journal of Medicine 10: 64)

- "The Physicians who object to yards, or courts, advocate, as a substitute, open verandahs guarded by lattice-work, such as are found at the Massachusetts State Lunatic Hospital, and at some of the other institutions of this country."

- Loudon, J. C., 1850, describing Riceborough, Ga.(p. 332)[14]

- "854. . . . The village of Riceborough . . . is very picturesque. Most of the houses have verandas.... (Hall's Sketches, &c., and Three Years in North America, &c.)" [Fig. 24]

- Mason, General John, c. 1830, describing Gunston Hall, seat of George Mason, Mason Neck, Va. (quoted in Rowland 1964: 1:98)[15]back up to history

- "The south front looked to the river; from an elevated little portico on this front you descended directly into an extensive garden, touching the house on one side."

Citations

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.) [16]

- "VERAN'DA, n. An oriental word denoting a kind of open portico, formed by extending a sloping roof beyond the main building. Todd."

- Downing, A. J., August 1836, "Remarks on the Fitness of the different Styles of Architecture for the Construction of Country Residences, and on the Employment of Vases in Garden Scenery" (American Gardeners' Magazine 2: 283)

- "There can scarcely be a more appropriate, agreeable and beautiful residence for a citizen who retires to the country for the summer, than a modern Italian villa, with its ornamented chimneys, its broad verandah, forming a fine shady promenade, and its cool breezy apartments."

- Downing, A. J., 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (p. 376)[17]back up to history

- "In this country no architectural feature is more plainly expressive of purpose in our dwelling-houses than the veranda, or piazza. The unclouded splendor and fierce heat of our summer sun, render this very general appendage a source of real comfort and enjoyment; and the long veranda round many of our country residences stands instead of the paved terraces of the English mansions as the place for promenade; while during the warmer portions of the season, half of the days or evenings are there passed in the enjoyment of cool breezes, secure under low roofs supported by the open colonnade, from the solar rays, or the dews of night. . . .

- "The various projections and irregularities, caused by verandas, porticoes, etc., serve to connect the otherwise square masses of building, by gradual transition with the ground about it."

- Ranlett, William H., 1849, The Architect ([1849] 1976: 1:21) [18]back up to history

- "Verandas, piazzas and porches are very expressive of purpose, and a dwelling should always have one or more of them; and balconies, which are decidedly ornamental and not without use."

- Elder, Walter, 1849, The Cottage Garden of America (p. 218)[19]

- "A. What a fine place you have got! that is a neat, well painted front fence; the flower plat between it and the house, with the evergreen in the centre is beautiful, and that verandah over the door, covered with flowering vines, looks well."

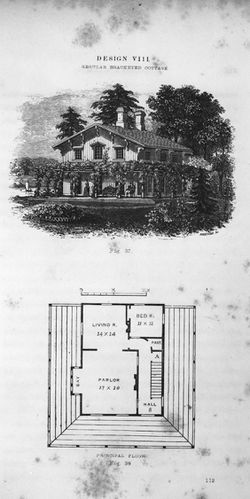

- Downing, A. J., 1850, The Architecture of Country Houses ([1850] 1968: 47, 109-10, 112-13, 118, 119-20, 122-23, 281, 308, 357-58)[20] back up to history

- "A much higher character is conferred on a simple cottage by a veranda than by a highly ornamental gable, because one indicates the constant means of enjoyment for the inmates—something in their daily life besides ministering to the necessities—while a more ornamental vergeboard shows something, the beauty of which is not so directly connected with the life of the owner of the cottage, and which is therefore less expressive, as well as less useful. . . .

- "[Referring to Design VII] The trellis-work veranda along the front of this cottage, and the bay-window in the best apartment, convey at once an expression of beauty arising from a sense of a superior comfort or refinement in the mode of living; and the whole exterior effect, without having any decided architectural merit, is one which we should be very glad to see followed in suburban houses of this class. . . . [Fig. 25]

- "In the Design [VIII] before us . . . there is an air of rustic or rural beauty conferred on the whole cottage by the simple, or veranda-like arbor, or trellis, which runs round three sides of the building; as well as an expression of picturesqueness, by the roof supported on ornamental brackets and casting deep shadows upon the walls.

- "To become aware how much this beauty of expression has to do with rendering this cottage interesting, we have only to imagine it stripped of the arbor-veranda and the projecting eaves, and it becomes in appearance only the most meagre and common-place building, which may be a house or a barn: at the most, it would indicate nothing more by its chimneys and windows, than that it is a human habitation, and not, as at present, that it is the dwelling of a family who have some rural taste, and some love for picturesque character in a house. ... [Fig. 26]

- "The larger expression of domestic enjoyment is conveyed by the veranda, or piazza. In a cool climate, like that of England, the veranda is a feature of little importance; and the same thing is true in a considerable degree in the northern part of New England. But over almost the whole extent of the United States, a veranda is a positive luxury in all the warmer part of the year, since in midsummer it is the resting place, lounging spot, and place of social resort, of the whole family, at certain hours of the day. It is not, however, an absolute necessity, like a kitchen or a bed-room, and, therefore, the smallest cottages, or those dwellings in which economy and utility are the leading considerations, are constructed without verandas. But the moment the dwelling rises so far in dignity above the merely useful as to employ any considerable feature not entirely intended for use, then the veranda should find its place; or, if not an architectural veranda, then, at least, the arbor-veranda, covered with foliage. . . . To decorate a cottage highly, which has no veranda-like feature, is, in this climate, as unphilosophical and false in taste, as it would be to paint a log-hut, or gild the rafters of a barn: unphilosophical, because all that relative beauty suggested by features which indicate a more refined enjoyment than what grows out of the necessities of life should first have its manifestation, since it is the most significant and noble beauty of which the subject is capable; and false in taste, because it is bestowing embellishment on the inferior and minor details, and neglecting the more important and more characteristic features of a dwelling."

- Downing, A. J., July 1850, "A Few Words on Rural Architecture" (Horticulturist 5: 10)

- "There are, indeed, few things so beautiful as a cottage of this kind, well designed and tastefully placed. There is nothing, all the world over, so truly rural and so unmistakably country-like as this very cottage, which has been developed in so much perfection in the rural lanes and amidst the picturesque lights and shadows of an English landscape. And for this reason, because it is essentially rural and country-like, we gladly welcome its general naturalization, (with the needful variation of the veranda, &c., demanded by our climate,) as the type of most of our country dwellings."

- Ranlett, William H., 1851, The Architect ([1851] 1976: 2:38, 53)[18]back up to history

- "The art of landscape gardening is an essential part of the accomplishments of an architect, for the main beauty of a rural dwelling is its harmonizing with the scene of which it forms a part. The same house that looked picturesque and beautiful on the top of a hill would look extravagant and whimsical on a plain; a country house with a southern front should have a projecting roof and a piazza; but one fronting the north would look more cold and cheerless by the addition of an overhanging roof or a veranda. Yet nothing is more common than to see houses in the country with gloomy-looking piazzas on the north side which is always in shadow, while the back part is left to scorch in the sun without even the protection of a hooded window to cast a shadow."

Images

Inscribed

J. C. Loudon, Nutt's hive placed in the front of a veranda, in The Suburban Gardener (1838), p. 714, fig. 307.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Villa for David Codwise, Elevation and Four Plans, 1835. "Veranda" is inscribed at the main entrance to the principal floor and off the drawing room.

- 1247 detail.jpg

Detail of Alexander Jackson Davis, Villa for David Codwise, Elevation and Four Plans, 1835. "Veranda" is inscribed at the main entrance to the principal floor and off the drawing room.

Anonymous, "Cottage Villa of Wm. J. Rotch, Esq. New Beford, Mass.", in The Horticulturist 4 (November 1849): pl. opp. p. 201. "Veranda" is inscribed on either side of the front porch.

Associated

Alexander Jackson Davis, "View in the Grounds at Blithewood", 1849, in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, (1849), frontispiece.

Frances Palmer, Wynne Tún, in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), vol. 2.

Attributed

Alexander Jackson Davis, "View N.W. at Blithewood," c.1841.

Notes

- ↑ William Russell Birch, The Country Seats of the United States of North America: With Some Scenes Connected with Them (Springland, Pa.: W. Birch, 1808), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Pierson, Jr., traces the origins of the feature, specifically found in Alexander Jackson Davis and A. J. Downing's work, to the awning or canopy partaking of an oriental flavor. In general, its origin was a semi-enclosed outdoor space that was not at all architectural but was related to the ornamental canopy or tent. This connection might explain why the detail flourished during the high romantic period in American architecture. See Pierson, American Buildings and Their Architects: Technology and the Picturesque, the Corporate and the Early Gothic Styles, vol. 2 (New York: Doubleday, 1978), 300-304, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Henry Latrobe. Impressions Respecting New Orleans: Diaries and Sketches, 1818–1820, ed. Samuel Wilson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1951), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kalm, The America of 1750: Peter Kalm's Travels in North America, trans. and rev. Adolph B. Benson (New York: Wilson-Erickson, 1937), 121. In his study of the veranda, Anthony D. King wrote, "It is generally accepted that the term 'verandah,' as used in England and France, and later in the British colonial world, came into the English landscape from India, the origins being either Persian, or, more likely Spanish or Portuguese." See King, The Bungalow: The Production of a Global Culture, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 266.

- ↑ This, of course, was not true because the veranda was featured in both John Plaw, Sketches for Country Houses, Villas and Rural Dwellings (London: S. Gosnell for J. Taylor, 1800), and J. B. Papworth, Penny Cyclopaedia (London: J. Taylor, 1818), as pointed out by King, The Bungalow, 266-67.

- ↑ Vincent J. Scully, The Shingle Style and the Stick Style: Architectural Theory and Design from Downing to the Origins of Wright (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1971), introduction.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1849), 370.

- ↑ William H. Pierson, Jr., American Buildings and Their Architects: Technology and the Picturesque, the Corporate and the Early Gothic Styles (New York: Doubleday, 1978), 302-4. See also King, The Bungalow, 267, where the author writes that "[a]n architectural note of the term, verandah," emphasized that "it was common as a fashionable architectural feature in England during the early nineteenth century," and does not recognize an American distinctiveness.

- ↑ Kalm, Pehr. 1937. The America of 1750: Peter Kalm’s Travels in North America. The English Version of 1770. 2 vols. New York: Wilson-Erickson. view on Zotero

- ↑ John Lambert, Travels through Canada, and the United States of North America in the Years 1806, 1807, and 1808, 2 vols. (London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Katharine M. Jones, The Plantation South (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1957), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alice B. Lockwood, ed., Gardens of Colony and State: Gardens and Gardeners of the American Colonies and of the Republic before 1840, 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s for the Garden Club of America, 1931-34), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Sir Charles Lyell, A Second Visit to the United States of North America, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, A new ed., cor. amd improved (London: Longman et al, 1850) view on Zotero

- ↑ Rowland, Kate Mason. 1964. The Life of George Mason: 1725-1792, 2 vols. (New York: Russell and Russell, 1964), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, vol. 1 (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero

- ↑ A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America; with a view to the improvement of country residences. Comprising historical notices and general principles of the art, directions for laying out grounds and arranging plantations, the description and cultivation of hardy trees, decorative accompaniments to the house and grounds, the formation of pieces of artificial water, flower gardens, etc.: with remarks on rural architecture, 4th ed. (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1849), view on Zotero

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 William H. Ranlett, The Architect, 2 vols. (New York: Da Capo, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter Elder, The Cottage Garden of America, (Philadelphia: Moss, 1849), view on Zotero

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses; Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-houses, and Villas (Originally published New York: D. Appleton, 1850. Reprint, New York: De Capo, 1968) view on Zotero