Meadow

See also: Lawn

History

According to lexicographer Noah Webster (1828), meadow referred “to the low ground on the banks of rivers. . . whether grassland, pasture, tillage, or wood land,” or low-lying lands that were particularly “appropriated to the culture of grass.” Both definitions of the term “meadow” were used in the American context.

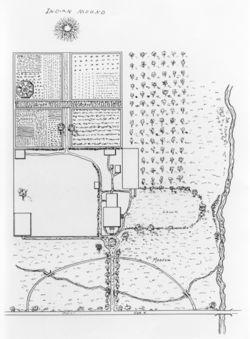

Maps of 18th-century New York and Boston show “salt meadows” along rivers. Like kitchen gardens or orchards, meadows played a key role in early American husbandry, and descriptive accounts of productive farms and estates often mention meadows, particularly when they gave the landscape a rich or well-cultivated appearance. Meadows ranged in size from the 12-acre meadow noted in a 1747 newspaper advertisement to the estimated 50 acres of meadow attached to an estate in Pennsylvania. In an 1807 plan of South Union, Ohio, a meadow was located in close proximity to the residences and between areas designated as woods and a cornfield [Fig. 1]. Since meadows were largely covered with grass, they could provide sustenance for cattle. Indeed, A. J. Downing, in describing the benefits of parks, frequently instructed homeowners to regard them as meadows where their cattle could graze. The cultivation of grass rendered “meadow” synonymous with “pasture,” which Webster defined as grounds covered with grass appropriated for the food of cattle, and hence these terms frequently were used interchangeably.

Although meadows were primarily associated with agricultural production, they were often part of a consciously designed landscape, as at “Newington,” Pennsylvania [Fig. 2]. They were also included in plans for plantations and ornamental farms (see Ferme ornée). 18th-century British gardening treatises, for example, endorsed the incorporation of agricultural features into ornamental contexts: Batty Langley (1728) recommended “Little Walks by purling streams in Meadows” as “delightful Entertainments.”

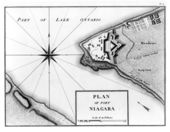

In many instances, meadows accomplished the same aesthetic results as lawns, including framing desired objects or views. At the 18th-century estate of Westover on the James River in Virginia, for example, meadows watered by canals lined the road leading to the mansion and signaled one’s arrival to the “improved grounds” surrounding the house. According to François-Alexandre-Frédéric duc de la Rochefoucauld Liancourt (1799), Dr. Baron of Charleston, South Carolina, wanted to buy an area of flat land between his garden and the river to convert it to a meadow that could frame views of the distant prospect. Pierre Pharoux, in his plan for Baron von Steuben’s estate in Mohawk Valley, New York, likewise used meadows carved out of woods to ensure visual access to the prospect [Fig. 3].

Meadows were closely related to parks and lawns; Downing on occasion referred to “meadow parks” and “meadow-lawns”. Nevertheless, in at least one article in the Horticulturist, he distinguished between lawns and meadows, arguing that lawns were composed of firm, close, and short grass, while coarser (and presumably taller) grasses with meadow flowers made up meadows. Moreover, lawns were often trimmed and rolled to maintain their appearance, while the primary method of maintaining meadows was to allow animals to graze.

Like lawns and bowling greens, the open grassy areas of meadows also provided space for sports and other leisure entertainments, as mentioned by a teacher in Salem, North Carolina, in 1817, who observed children playing round ball in the meadow of a tavern.

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Anonymous, August 17, 1747, describing property for sale in Somerset County, NJ (New York Gazette)

- “TO BE SOLD, A pleasant Country Seat, fitting for a Gentleman or Store-keeper. . . containing about 90 Acres, including a piece of English Meadow about 12 Acres, and more may be made, about 40 Acres being clear, the remainder Wood-Land.”

- Kalm, Pehr, October 4, 1748, describing his journey from Philadelphia to Wilmington, DE (1937: 1:81–82)[1]

- “I rode now through woods of several sorts of trees and now over pieces of land which had been cleared of the wood and which at present were grain fields, meadows and pastures. The farmhouses stood single, sometimes near the roads, and sometimes at a little distance from them, so that the space between the road and the houses was taken up with small cultivated tracts and meadows. . . The fields bore partly buckwheat, which was cut, partly corn, and partly wheat.”

- Brook, Elizabeth, 1756, describing Doughoregan Manor, seat of Charles Carroll (of Annapolis), Howard County, MD (Maryland Historical Society, A. E. Carroll Papers)

- “This place. . . is greatly improved, a fine, flourishing orchard with a variety of choice fruit, the garden inlarged and a stone wall built around it, 2 fine meadows.”

- Alexiowitz, Iwan, 1769, describing Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, vicinity of Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Darlington 1849: 50)

- “The whole store of nature’s kind luxuriance seemed to have been exhausted on these beautiful meadows; he made me count the amazing number of cattle and horses now feeding on solid bottoms, which but a few years before had been covered with water.”

- Shippen, Thomas Lee, December 31, 1783, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd III, on the James River, VA (1952: n.p.)[2]

- “You pass thro’ two gates, and from the second, which leads you into the improved grounds, may be seen a village of quarters as they are called for negroes. The road you get into upon opening this gate is spacious and very level bounded on either side by a handsome ditch & fence which divide the road from fine meadows whose extent is greater than the eye can reach; and on one side you see the river through trees of different sorts. These meadows well watered with canals, which communicate with each other across the road give occasion every 50 yards for a bridge; and between every two bridges are two gates one on each side the road.”

- La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, François Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de, May 6, 1795, describing Pottsgrove, PA (1800: 1:35)[3]

- “The landscape is beautiful along this road, abounding with a great variety of fine views, wonderfully enlivened by the verdure of the cornfields and meadows. . . If agriculture were better understood in these parts; if the fields were well mowed and well fenced; and if some trees had been left standing in the middle or on the borders of the meadows, the most beautiful parts of Europe could not be more pleasing.”

- La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, François Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de, 1795–97, describing an estate in Pennsylvania (1800: 1:101)[3]

- “The cultivated ground amounts in the whole to one hundred and twenty acres, fifty of which are laid out in artificial meadows, and thirty-six in orchards for apple and peach-trees. The meadows are beautiful, and the fields in good order.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing New England (1821: 1:18, 2:335)[4]

- “[vol. 1]. . . A succession of New-England villages, composed of neat houses, surrounding neat school-houses and churches, adorned with gardens, meadows and orchards, and exhibiting the universally easy circumstances of the inhabitants, is, at least in my own opinon, one of the most delightful prospects, which this world can afford. . .

- “[vol. 2] New England villages. . . are built in the following manner. . .

- “The lot, on which the house stands, universally styled the home lot, is almost of course a meadow, richly cultivated, covered during the pleasant season with verdure, and containing generally a thrifty orchard. It is hardly necessary to observe, that these appendages spread a singular cheerfulness, and beauty, over a New-England village; or that they contribute largely to render the house a delightful residence.”

- Parkinson, Richard, 1798–1800, describing Orange Hill, near Baltimore, MD (1805: 1:163–64)[5]

- “My first work on the farm was to dress the meadows; which were called fine; though the greater part of them in England would not have been thought worthy of being called meadows at all, being overrun with briars and weeds of different description. Their state indeed was such, that when I mowed them, I sometimes in making hay did not know whether it was worth putting together, or not.”

- La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, François Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de, 1799, describing Fitterasso, estate of Dr. Baron, Charleston, SC (1800: 2:435–36)[3]

- “This small plantation, named Fitterasso, consists of four hundred acres, and cost him four thousand two hundred and eighty dollars; it is situated on a small eminence near the river. The site for the house, for none has hitherto been built, is the most pleasant spot which could be chosen in this flat, level country, where the tedious sameness of the woods is scarcely variegated by some houses, thinly scattered, and where it is hardly possible to meet with a pleasant landscape. His garden is separated from the river by a morass, nearly drained; the whole extent of the northern bank of the river is nearly of the same description. Dr. Baron intends to purchase this intervening space, and to convert it into meadow-ground. This alteration will improve the prospect, without rendering it a charming vista.”

- Ogden, John Cosens, 1800, describing Bethlehem, PA (1800: 13)[6]

- “The variety of walks, rows of trees, and the plenty with which the gardens and meadows were stored, displayed taste, industry and economy.”

- Martin, William Dickinson, 1809, describing the pleasure grounds at Salem Academy, Salem, NC (quoted in Bynum 1979: 29)[7]

- “‘Next, I visited a flower garden belonging to the female department. . . But it is situated on a hill, the East end of which is high & abrupt. . .

- “‘From the extremity of this place descended in different directions, two rows of steps, & joined again at the bottom, of the hill, where was a beautiful spring, from which issued a brisk current, winding in a serpentine course through a handsome meadow, ’til it reached a brook about a quarter of a mile distant. This place was designed for literary repast, & evening amusement—is certainly well adapted for either or both.’”

- Peale, Charles Willson, 1810, in a letter to his son, Rembrandt Peale, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (quoted in Rudnytzky 1986: 42)[8]

- “I am often pleased with the solemn groves skirting my meadows in mahestic [sic] silence and cool appearance.”

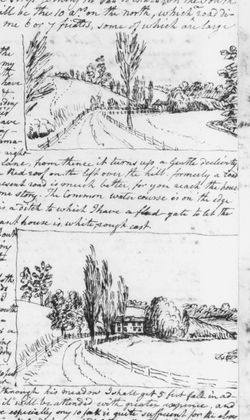

- Peale, Charles Willson, 1810, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (quoted in Miller and Ward 1991: fig. 87)[9]

- “In this view imagine that you see a beautiful Meadow on the right. . . The Common water course is on the edge of the Meadow on the right and the doted [sic] line is a ditch to which I have a flood-gate to let water on the Meadow at Pleasure.” [Fig. 4]

- Pursh, Frederick, 1814, describing the plants of North America (1814: 1:v)[10]

- “Her [America] forests produce an endless variety of useful and stately timber trees; her woods and hedges the most ornamental flowering shrubs, so much admired in our pleasure grounds; and her fields and meadows a number of exceedingly handsome and singular flowers (many of them possessing valuable medicinal virtues), different from those of other countries.”

- Teacher at Moravian Boys School, 1817, describing Salem, NC (quoted in Bynum 1979: 52)[7]

- “This afternoon I went with the children. . . I took them to the tavern meadow, where they played a little round ball.”

- du Pont, Sophie Madeleine, July 21, 1837, describing her visit to a meadow (quoted in Low and Hinsley 1987: 178)[11]

- “They were making hay in the undulating meadow, which added to the picturesque effect of the scenery [sic] There is here a very convenient chaise a porteur in which I am carried, or the blackies here express it, toted, from one place to another—”

- Lyell, Sir Charles, September 22, 1845, describing Boston, MA (1849: 1:30)[12]

- “The extreme heat of summer does not allow of the green meadows and verdant lawns of England, but there are some well-kept gardens here—a costly luxury where the wages of labor are so high.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, October 1848, describing Geneseo, seat of James S. Wadsworth, Genesee River Valley, NY (Horticulturist 3: 163–65)[13]

- “The great agricultural estate of the WADSWORTH family, is the pride and centre of this precious family. That magnificent tract, of thousands of acres of the finest land, which surpasses in extent and value many principalities of the old world; those broad meadows, where herds of the finest cattle crop the richest herbage, or rest under the deep shade of giant trees. . .

- “And what a prospect! The whole of that part of the valley embraced by the eye-say a thousand acres—is a park, full of the finest oaks,—and such oaks as you may have dreamed of, (if you love trees,) or, perhaps, have seen in pictures by CLAUDE LORRAINE, or our own DURAND; but not in the least like those which you meet every day in your woodland walks through the country at large. Or rather, there are thousands of such as you may have seen half a dozen examples of in your own country. . .

- “No underwood, no bushes, no thickets; nothing but single specimens or groups of giant old oaks, (mingled with, here and there, an elm,) with level glades of broad meadow beneath them! An Englishman will hardly be convinced that it is not a park, planted by the skilful hand of man hundreds of years ago.

- “This great meadow park is filled with herds of the finest cattle—the pride of the home—farm.” [Fig. 5]

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, August 1851, “The Annual Cattle Sale at Mount Fordham,” describing Mount Fordham, seat of Lewis G. Morris, New York, NY (Horticulturist 6: 372)[14]

- “Around the house at Mount Fordham, extends on all sides a kind of meadow-lawn, enclosed and divided by pretty wire fences of various patterns. This lawn is kept short by the grazing of improved dairy stock, and we were glad to see successfully practiced what we have been commending so strongly of late to our readers, as the most available point of English country places, that we saw on the other side of the Atlantic—that is the maintenance of a neat and handsome lawn about a country house, not only without the expense of mowing, but with united profit and beauty—the profit of grazing the grass and the beauty—the real pastoral beauty—of fine cattle, soft turf, and pleasant groups of trees, as the home landscape of our country places generally. By adopting this course, the hay-field aspect of many so-called gentlemen’s country-seats, would disappear, and a more complete and satisfactory lawn or park be acquired, with no loss of money, and the attainment of a higher species of keeping to one’s country home.” [Fig. 6]

Citations

- Langley, Batty, 1728, New Principles of Gardening (1728; repr., 1982: 195–201)[15]

- “General DIRECTIONS, &c. . .

- “XIX. That in those serpentine Meanders, be placed at proper Distances, large Openings, which you surprizingly come to; and in the first are entertain’d with a pretty Fruit-Garden, or Paradice-Stocks. . . from which you are insensibly led through the pleasant Meanders of a shady delightful Plantation; first, into an oven [sic] Plain environ’d with lofty Pines. . . secondly, into a Flower-Garden. . . and from thence through small Inclosures of Corn, open Plains, or small Meadows. . .

- “XXVIII. Distant Hills in Parks, &c. are beautiful Objects, when planted with little Woods; as also are Valleys, when intermix’d with Water, and large Plains; and a rude Coppice in the Middle of a fine Meadow, is a delightful Object.

- “XXIX. Little Walks by purling streams in Meadows, and through Corn-Fields, Thickets, &c. are delightful Entertainments.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 2:n.p.)[16]

- “MEAD. n.s. [meade, Sax.] Ground somewhat watery, not plowed, but covered with grass and flowers.

- “ME’ADOW.”

- Ware, Isaac, 1756, A Complete Body of Architecture (1756: 645, 651)[17]

- “A meadow and its hedge excelled all the beauty of our former gardens; because the parterre there afforded only the ill fruits of labour, and the hedge lost the very vegetable character. . .

- “Let us lead such as still prefer it [[[geometric style|geometric]] flower beds] to more free dispositions, into a May meadow, full of the common weedy flowers of that healthy season, and terminated by a hawthorn hedge in bloom. . .”

- Miller, Philip, 1759, The Gardeners Dictionary (1759: n.p.)[18]

- “Under the general title of Meadow, is commonly comprehended all Pasture land, or at least all Grass Land, which is mown for Hay; but I choose rather to distinguish such land only by this Apellation, which is so low, as to be too moist for Cattle to graze upon them in winter, being too wet to admit heavy cattle, without poaching & spoiling the Sward, and those grass lands which I shall distinguish by the title of pasture.”

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (1789: n.p.)[19]

- “MEADOW, med’-do. s. A rich pasture ground, from which hay is made.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[20]

- “MEAD, MEADOW, n. meed, med’o. [Sax. moede, moedewe; G. matte, a mat, and a meadow; Ir. madh. The sense is extended or flat depressed land. It is supposed that this word enters into the name Mediolanum, now Milan, in Italy; that is, mead-land.]

- “A tract of low land. In America, the word is applied particularly to the low ground on the banks of rivers, consisting of a rich mold or an alluvial soil, whether grass land, pasture, tillage, or wood land; as the meadows on the banks of the Connecticut. The word with us does not necessarily imply wet land. This species of land is called, in the western states, bottoms, or bottom land. The word is also used for other low or flat lands, particularly lands appropriated to the culture of grass.

- “The word is said to be applied in Great Britain to land somewhat watery, but covered with grass. Johnson.

- “Meadow means pasture or grass land, annually mown for hay; but more particularly, land too moist for cattle to graze on in winter, without spoiling the sward. Encyc. Cyc.

- “[Mead is used chiefly in poetry.]”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, November 1846, “A Chapter on Lawns” (Horticulturist 1: 204)[21]

- “After your lawn is once fairly established, there are but two secrets in keeping it perfect— frequent mowing and rolling. Without the first, it will soon degenerate into a coarse meadow; the latter will render it firmer, closer, shorter, and finer every time it is repeated.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, March 1851, “The Management of Large Country Places” (Horticulturist 6: 106)[22]

- “Considerable familiarity with the country-seats on the Hudson, enables us to state that for the most part, few persons keep up a fine country place. . .

- “The remedy for this unsatisfactory condition of the large country places is, we think, a very simple one—that of turning a large part of their areas into park meadow, and feeding it, instead of mowing and cultivating it.

- “The great and distinguishing beauty of England, as every one knows, is its parks. And yet the English parks are only very large meadows, studded with great oaks and elms—and grazed—profitably grazed, by deer, cattle and sheep.”

Images

Inscribed

Pierre Pharoux, “General Map of the honorable Wm. frederic Baron of Steuben’s Mannor”, c. 1793. The “60 acres of Meadow” is indicated at “j” in the four squares below the hemicycle.

Anonymous, A plan of the section of land on which the Believers live in the state of Ohio, Nov. 7, 1807. “Meadow” is noted in the center between the woods and cornfield.

Charles Willson Peale, Sketches of Belfield, 1810.

Joshua Barney, Map of Hampton, 1843. Courtesy: Hampton National Historic Site, National Park Service.

Anonymous, “View in the Meadow Park at Geneseo,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 3, no. 4 (October 1848): pl. opp. 153.

Associated

Charles Willson Peale, Ground plot of Belfield, 1810.

Anonymous, “Mount Fordham—the Country Seat of Lewis G. Morris, Esq.,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 6, no. 8 (August 1851): pl. opp. 345.

Attributed

Nicholas Garrison, A View of Bethlehem, one of the Brethren’s Principal Settlements, in Pennsylvania, North America, 1757.

Francis Guy, Perry Hall, Slave Quarters with Field Hands at Work, c. 1805.

Anonymous, “Beaverwyck, the Seat of Wm. P. Van Rensselaer, Esq.,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), pl. opp. 51, fig. 7.

Notes

- ↑ Pehr Kalm, The America of 1750: Peter Kalm’s Travels in North America. The English Version of 1770, 2 vols. (New York: Wilson-Erickson, 1937), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Lee Shippen, Westover Described in 1783: A Letter and Drawing Sent by Thomas Lee Shippen, Student of Law in Williamsburg, to His Parents in Philadelphia (Richmond, VA: William Byrd Press, 1952), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 François-Alexandre-Frédéric duc de La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, Travels through the United States of North America, the Country of the Iroquois, and Upper Canada, in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797, ed. Brisson Dupont and Charles Ponges, trans. H. Newman, 2nd ed., 4 vols. (London: R. Philips, 1800), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels in New England and New York, 4 vols. (New Haven, CT: Timothy Dwight, 1821), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Parkinson, A Tour in America, 1798, 1799, and 1800: Exhibiting Sketches of Society and Manners, and a Particular Account of the American System of Agriculture, with Its Recent Improvements, 2 vols. (London: J. Harding, 1805), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John C. Ogden, An Excursion into Bethlehem & Nazareth, in Pennsylvania, in the Year 1799 (Philadelphia: Charles Cist, 1800), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Flora Ann L. Bynum, Old Salem Garden Guide (Winston-Salem, NC: Old Salem, 1979), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kateryna A. Rudnytzky, “The Union of Landscape and Art: Peale’s Garden at Belfield” (Honors thesis, LaSalle University, 1986), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 3, The Belfield Farm Years, 1810–1820 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Pursh, Flora Americae Septentrionalis; Or, a Systematic Arrangement and Description of the Plants of North America, 2 vols. (London: White, Cochrane, & Co., 1814), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Betty-Bright Low and Jacqueline Hinsley, Sophie Du Pont, A Young Lady in America: Sketches, Diaries, & Letters, 1823–1833 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sir Charles Lyell, A Second Visit to the United States of North America, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “The Meadow Park in Geneseo,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 4 (October 1848): 163–66, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “The Annual Cattle Sale at Mount Fordham,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 6, no. 8 (August 1851): 372–73, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Batty Langley, New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c. (London: A. Bettesworth and J. Batley, etc., 1728; repr., New York: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Isaac Ware, A Complete Body of Architecture (London: T. Osborne and J. Shipton, 1756), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Philip Miller, The Gardeners Dictionary: Containing the Methods of Cultivation and Improving the Kitchen, Fruit, and Flower Garden, 7th ed. (London: Philip Miller, 1759), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas A. Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews. . . , 5th ed. (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “A Chapter on Lawns,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 1, no 5. (November 1846): 202–4, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “The Management of Large Country Places,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 6, no. 3 (March 1851): 105–8, view on Zotero.