Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery

The Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, located on the west bank of the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, was developed by John Bartram (1699–1777) for scientific and commercial purposes and maintained by three generations of his family. The encyclopedic range of plants comprised native examples discovered on botanical expeditions made by Bartram and his son, William (1739–1823), as well as exotic specimens sent to him from other parts of the world.

Overview

Alternate Names: John Bartram & Sons; Bartram’s Garden; Bartram House and Garden; Kingsess Gardens

Site Dates: 1730s to present

Site Owner(s): John Bartram (1699–1777); John Bartram Jr. (1743–1812); Ann Bartram Carr (1779–1858) and Col. Robert Carr (1778–1866); City of Philadelphia

Location: Philadelphia, PA

Condition: altered

View on Google maps

History

Through a number of property transactions made between 1728 and 1740, John Bartram acquired more than 287 acres of rich, well-watered farmland on the Schuylkill River at Kingsessing, about three miles from the center of Philadelphia. Bartram was the son of a Quaker farmer in rural Pennsylvania, and he devoted most of his new property to agriculture. In addition to cultivating grains and raising livestock, he planted a kitchen garden in 1729 and built a stone farmhouse in 1731.[1] Around the same time, he developed a garden on six or seven acres of ground sloping from the house down to the river.[2]

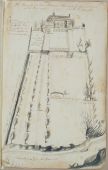

A drawing of the garden dating to 1758 identifies no specific plant materials, but clearly indicates a terraced garden divided into four well-defined zones [Fig. 1]. The area directly behind the house is labeled “Common Flower Garden,” with an “Upper Kitchen Garden” to its north and “A new flower Garden” (measuring twenty-six by ten yards) to the south. Board fences enclose each of these areas. A stone retaining wall punctuated by steps marks the transition from the upper gardens down to the much larger “Lower Kitchen Garden,” laid out on a slope that ended at the banks of Schuylkill River. An oval-shaped pond at the center of the lower garden connects to the “spring or milk House,” located in the shade of a large tree near the garden’s northern fence. Plantings interspersed along this fence may represent espaliered trees.[3] Three long alleys of trees running the full length of the garden are labeled “Walks 150 yards long of a moderate descent.” Following his visit to the property in 1787, Manasseh Cutler described this feature as “a walk to the river, between two rows of large, lofty trees,” adding that the trees were of “all of different kinds.” According to Cutler, the walk terminated in a summerhouse on the river bank (view text).

From early on Bartram provided trees, shrubs, bulbs, roots, and seeds to many of his neighbors in Philadelphia, including William Hamilton of The Woodlands, Charles Willson Peale of Belfield, and Thomas Penn of Springettsbury. His business expanded exponentially after he entered into an informal partnership with the London merchant Peter Collinson who was his faithful correspondent and advocate for more than thirty years. With the encouragement of Collinson and a growing British and European clientele, Bartram traveled to most of the American colonies, collecting plants and seeds to transplant and cultivate at his garden. During Bartram’s frequent absences from home on botanical expeditions, the garden was managed by his wife, Ann Mendenhall Bartram (1703–1789).

Bartram initially gathered plants for his garden from the countryside near his house. Over time, he ventured farther afield, eventually exploring remote wilderness areas from New York to Florida. His extensive field experience distinguished him from most of the gardeners and botanists of his day. Informed by personal knowledge of the natural habitats of the plants in his collection, he transplanted new finds to those sections of his property that most closely approximated the environmental conditions and terrain in which he had first encountered them.[4] Bartram’s insatiable botanical curiosity and far-ranging expeditions placed a premium on comprehensiveness, as did the function of his garden as a supplier of plants for sale and exchange. Initiating a trading relationship with J. Slingsby Cressy, a physician and botanist in Antigua, Bartram emphasized the breadth of his interests: “Whatsoever whether great or small ugly or handsom sweet or stinking . . . every thing in the universe in their own nature appears beautiful to mee.”[5] Twenty years later, in a letter to Collinson, he crowed, “I can challenge any garden in America for variety.”[6] Plants from Bartram’s garden survive in a number of European and American herbaria.[7]

Despite his love of variety, Bartram was initially reluctant to cultivate delicate plants that required inordinate care to survive Philadelphia’s climate. “I don’t greatly like tender plants what wont bear our severe winters,” he remarked to Philip Miller (1791–1771), curator of the Chelsea Physick Garden, in a letter of June 20, 1757 (view text). This position changed somewhat in 1760, the year of Bartram’s first visit to South Carolina, when he decided to build a greenhouse. As he explained to Collinson, his plan was to construct the building of stone and to grow “some pretty flowering winter shrubs, and plants for winter’s diversion,” rather than the exotic orange trees and tropical plants that several of his neighbors cultivated. Bartram erected a modest, one-and-a-half story building of stone with an east facing window, which was completed by December 1762 when he informed Collinson that he had included an external fireplace and two flues in the back wall for heat.[8] From the 1760s on, the addition of warm-weather Carolina plants transformed Bartram’s garden, enlivening it with brilliantly colored flowers.[9]

Following John Bartram's death in 1777, the nursery business continued under the supervision of John Bartram Jr. (1743–1812) with assistance from his elder brother, the natural history explorer and illustrator William Bartram (1739–1823). Under their stewardship, the garden became an outdoor classroom. Benjamin Smith Barton (1766–1815), the first professor of natural history at the University of Pennsylvania, brought his students to the garden to study live plants in situ, and the Bartrams noted with pride that their family’s botanic garden “may with propriety and truth be called the Botanical Academy of Pennsylvania, since . . . the Professors of Botany, Chemistry, and Materia Medica, attended by their youthful train of pupils, annually assemble here during the Floral season.”[10]

John Jr. and William continued to expand the business, adding a second greenhouse around 1790, and another in 1817.[11] The fame of the garden attracted many distinguished visitors. George Washington paid a visit on June 10 and September 2, 1787 while in Philadelphia for the Continental Convention.[12] Although he disparaged the garden in his diary, describing it as “not laid off with much taste, nor was it large,” he was impressed by the many “curious pl[an]ts. Shrubs & trees, many of which are exotics” (view text). Two years later he requested a catalogue from the Bartrams (view text) and in 1792 ordered at least 106 varieties of plants. Three hundred trees and shrubs from Bartram’s Garden were planted in ornamental ovals at Mount Vernon that spring.[13]

In 1807 the Bartrams distributed A Catalog of Trees, Shrubs, and Herbaceous Plants Indigenous to the United States of America, cultivated and Disposed of by John Bartram and Son at their Botanical Garden at Kingessing, near Philadelphia. To which is added a Catalog of Foreign Plants Collected from Various Parts of the Globe. On John Jr.’s death in 1812, his daughter, Ann Bartram Carr (1779–1858), was responsible for maintaining the garden and operating the business. She had learned the science of botany and the art of botanical illustration from her uncle William and together with her husband Colonel Robert Carr (1778–1866) and his son John Bartram Carr (1804–1839), she enlarged the commercial nursery and continued the international trade in seeds and plants. At its peak the enterprise operated ten greenhouses and maintained a collection of over 1400 native and 1000 exotic plant species.In 1838 the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad laid out the first route south of Philadelphia, cutting through the west side of the Bartram-Carr property. Later in the century, the company's single track was expanded to two. Having continued to grow and thrive through three generations of the Bartram family, Bartram’s Botanic Garden and Nursery began to experience financial difficulties and was sold out of the family in 1850. The historic garden was purchased by the wealthy railroad industrialist Andrew M. Eastwick (1811–1879), who maintained it as a private park.[14] Today it is a 45-acre National Historic Landmark, operated by the John Bartram Association in cooperation with Philadelphia Parks and Recreation.

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Bartram, John, 1740/41, letter to Peter Bayard describing hedges (1992: 174–75)[15]

- “As to the evergreens for pyramids that which is called in Europe the silver fir in new England hemlock & our people spruice is esteemed one of the most beautiful evergreens for showey pyramids & yew & holy is also much esteemed . . . for hedges in A garden I like our red cedar or Juniper for tall natural pyramids the white or Lord weymouth pine & balm of gilead fir the larix & spruce fir & abor vita.”

- Bartram, John, June 11, 1743, letter to Peter Collinson, describing the garden of Dr. Christopher Witt in Germantown, PA (1992: 215–16)[15]

- “I have lately been to visit our friend Doctor wit [Witt] where I spent 4 of 5 very agreeable sometimes in his garden wehre I viewed every kind of plant I believe that grew therin. . . . I observed particularly the Doctors famous Lychnis which thee hath dignified so highly, is I think unworthy of that Character our swamps & low grounds is full of them I had so contemptible an opinion of it as not to think it worthy sending nor afford it room in my garden.”

- Kalm, Pehr, September 25, 1748, Travels into North America (1770: 1:112–13)[16]

- “Mr. John Bartram is an Englishman, who lives in the country about four miles from Philadelphia. He has acquired a great knowledge of natural philosophy and history, and seems to be born with a peculiar genius for these sciences. . . . He has in several successive years made frequent excursions into different distant parts of North America, with an intention of gathering all sorts of plants which are scarce and little known. Those which he found he has planted in his own botanical garden, and likewise sent over their seeds or fresh roots to England. We owe to him the knowledge of many scarce plants, which he first found, and which were never known before.”

- Bartram, John, February 12, 1753, letter to Jared Eliot describing hedges (1992: 342)[15]

- “About 16 years past I planted a hedge of red Cedars one foot long on a small bank About 2 foot asunder[.] they growed so well that in 3 or 4 years I had a A fine hedge 4 foot high 2 foot thick, & so close that A bird could not fly thro it.”

- Garden, Alexander, November 4, 1754 to Cadwallader Colden (quoted in Colden 1920: 471–72)[17]

“I have met wt very Little new in the Botanic way unless Your acquaintance Bartram. . . .

“His garden is a perfect portraiture of himself, here you meet wt a row of rare plants almost covered over wt weeds, here with a Beautiful Shrub, even Luxuriant Amongst Briars, and in another corner an Elegant & Lofty tree lost in common thicket—on our way from town to his house he carried me to severall rocks & Dens where he shewed me some of his rare plants, which he had brought from the Mountains &c. In a word he disdains to have a garden less than Pensylvania [sic] & Every den is an Arbour, Every run of water, a Canal, & every small level Spot a Parterre, where he nurses up some of his Idol Flowers & cultivates his darling productions.”

- Bartram, John, June 20, 1757, letter to Philip Miller (1992: 423–24)[15] back up to History

- “I dont greatly like tender plants what wont bear our severe winters but perhaps annual plants that would perfect thair seeds with you without the help of A hot bed in the spring will do with us in the open ground. . . . Two roots of a sort is enough. I don’t want much of any one species but variety pleaseth me.”

- Bartram, John, February 18, 1758, letter to Philip Miller in London (1992: 456–58)[15]

- “At present my fancy runs all upon the living curious seeds cuttings of bulbous roots[.] fibrous roots is difficult to send . . . for now every few nights I dream of seeing & gathering the finest flowers & roots to plant in my garden[.] pray my dear friend oblige me with one or two of thy best sorts[.] I want but one of A sort but I love variety [.] pray don’t let our dutch outdo me.”

- Bartram, John, June 24, 1760, in a letter to Peter Collinson, describing his plans for the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (quoted in Darlington 1849: 224)[18]

- “Dear friend, I am going to build a greenhouse. Stone is got; and hope as soon as harvest is over to begin to build it, to put some pretty flowering winter shrubs, and plants for winter’s diversion; not to be crowded with orange trees, or those natural to the Torrid Zone, but such as will do, being protected from frost.”

- Bartram, John, July 19, 1761, letter to Peter Collinson (1992: 529)[15]

- “I have now A glorious appearance of Carnations from thy seed—the brightest color that ever eyes beheld now, what with thine dr. Witts & others I can challenge any garden in America for variety.”

- Bartram, John, May 1763, letter to Peter Collinson (1992: 594)[15]

- “My garden now makes A glorious appearance I have A fine anonis with A large spike of blew flowers in full bloom which I gathered in Potemack 3 years ago . . . my great carolina saracena is in bloom . . . it is a glorious odd flower A goldish color & striped.”

- Bartram, John, May 1, 1764, letter to Peter Collinson (1992: 627–28)[15]

- “I have many Carolina seeds come up this spring in the bed I sowed when I cam home . . . . Doctor Shippen gave me some seed last summer which he brought from the south of Europe one fine sumach grew 18 inches . . . I sheltered them with boards & thay are now very fresh the first I transplanted to one side of my walks. . . . Last summer there came up in my greenhouse from east India seed formerly sowed there an odd kind of Sumach (as I take it to be)[.] it growed in A few months near 4 foot high & continued green & growing all winter & this spring I planted it it out to take its chance it shoots vigorously & almost as red as crimson how it will stand next winter I cant say but I intend to cover the ground well above its root. . . . Last summer there came up in my greenhouse from east India seed formerly sowed there an odd kind of Sumach (as I take it to be)[.] it fgrowd in A few months near 4 foot high & continued green & growing all winter & this spring I planted it it out to take its chance it shoots vigorously & almost as red as crimson how it will stand next winter I cant say but I intend to cover the ground well above its root.”

- Bartram, John, June 1766, to Peter Collinson (London 1992: 668–69)[15]

- “I have brought home with me A fine Collection of strange florida plants.”

- Alexiowitz, Iwan, 1769, describing Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (quoted in Darlington 1849: 50)[18]

- “The whole store of nature’s kind luxuriance seemed to have been exhausted on these beautiful meadows; he made me count the amazing number of cattle and horses now feeding on solid bottoms, which but a few years before had been covered with water. Thence we rambled through his fields, where the rightangular fences, the heaps of pitched stones, the flourishing clover, announced the best husbandry, as well as the most assiduous attention. . . . He next showed me his orchard, formerly planted on a barren, sandy soil, but long since converted into one of the richest spots in that vicinage.”

- Al—z, Mr. Iw—n, c. 1770, describing John Bartram and the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (quoted in Crèvecœur 1783: 248, 254)[19]

“Let us . . . pay a visit to Mr. John Bertram [sic], the first botanist, in this new hemisphere. . . . It is to this simple man that America is indebted for several useful discoveries, and the knowledge of many new plants. . . .

“Every disposition of the fields, fences, and trees, seemed to bear the marks of perfect order and regularity, which in rural affairs, always indicate a prosperous industry . . .

“From his study we went into the garden, which contained a great variety of curious plants and shrubs; some grew in a green-house, over the door of which were written these lines,

- “Slave to no sect, who takes no private road,

- “But looks through nature, up to nature’s God!”

- Washington, George, June 10, 1787, describing the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (1979: 5:166)[20] back up to History

- “[We] rid to see the Botanical garden of Mr. Bartram; which, tho’ Stored with many curious plts. Shrubs & trees, many of which are exotics was not laid off with much taste, nor was it large.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 14, 1787, describing the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (1888: 1:272–74)[21] back up to History

- “We crossed the Schuylkill, at what is called the lower ferry, over the floating bridge, to Gray’s tavern, and, in about two miles, came to Mr. Bartram’s seat. We alighted from our carriages, and found our company were : Mr. [Caleb] Strong, Governor [Alexander] Martin, Mr. [George] Mason and son, Mr. [Hugh] Williamson, Mr. [James] Madison, Mr. [John] Rutledge, and Mr. [Alexander] Hamilton, all members of Convention, Mr. Vaughan, and Dr. [Gerardus] Clarkson and son. Mr. Bartram lives in an ancient Fabric, built with stone, and very large, which was the seat of his father. His house is on an eminence fronting to the Schuylkill, and his garden is on the declivity of the hill between his house and the river. We found him, with another man, hoeing in his garden, in a short jacket and trowsers, and without shoes or stockings. He at first stared at us, and seemed to be somewhat embarrassed at seeing so large and gay a company so early in the morning. Dr. Clarkson was the only person he knew, who introduced me to him, and informed him that I wished to converse with him on botanical subjects, and, as I lived in one of the Northern States, would probably inform him of trees and plants which he had not yet in his collection; that the other gentlemen wished for the pleasure of a walk in his garden. I instantly entered on the subject of botany with as much familiarity as possible, and inquired after some rare plants which I had heard that he had. He presently got rid of his embarrassment, and soon became very sociable, which was more than I expected, from the character I had heard of the man. I found him to be a practical botanist, though he seemed to understand little of the theory. We ranged the several alleys, and he gave me the generic and specific names, place of growth, properties, etc., so far as he knew them. This is a very ancient garden, and the collection is large indeed, but is made principally from the Middle and Southern States. It is finely situated, as it partakes of every kind of soil, has a fine stream of water, and an artificial pond, where he has a good collection of aquatic plants. There is no situation in which plants or trees are found but that they may be propagated here in one that is similar. But every thing is very badly arranged, for they are neither placed ornamentally nor botanically, but seem to be jumbled together in heaps. The other gentlemen were very free and sociable with him, particularly Governor Martin, who has a smattering of botany and a fine taste for natural history. There are in this garden some very large trees that are exotic, particularly an English oak, which he assured me was the only one in America. He had the Pawpaw tree, or Custard apple. It is small, though it bears fruit ; but the fruit is very small. He has also a large number of aromatics, some of them trees, and some plants. One plant I thought equal to cinnamon. The Franklin tree is very curious. It has been found only on one particular spot in Georgia. . . . From the house is a walk to the river, between two rows of large, lofty trees, all of different kinds, at the bottom of which is a summer-house on the bank, which here is a ledge of rocks, and so situated as to be convenient for fishing in the river, where a plenty of several kinds of fish may be caught. Mr. Bartram showed us several natural curiosities in the place where he keeps his seeds; they were principally fossils. He appeared fond of exchanging a number of his trees and plants for those which are peculiar to the Northern States. We proposed a correspondence, by which we could more minutely describe the productions peculiar to the Southern and Northern States.

- “About nine, we took our leave of Mr. Bartram, who appeared to be well pleased with his visitors, and returned to Gray’s tavern, where we breakfasted.”

- Lear, Tobias to Clement Biddle, October 7, 1789 (1993: 4:124–25)[22]

- “The President will thank you to get from Mr Bartram a list of the plants & shrubs which he has for sale, with the price affixed to each, and also a note to each of the time proper for transplanting them, as he is desireous of having some sent to Mount Vernon this fall if it is proper.

- “It is customary for those persons who publish lists of their plants &c. to insert many which they have had, but which have been all disposed of—the President will therefore wish to have a list only of what he actually has in his Gardon.”

- Niemcewicz, Julian Ursyn, March 24, 1798, journal entry describing the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (1965: 52)[23]

- “We arrived at the farmhouse. It is built of great stones wiht a few rustic columns of the same material. The gardens extends as far as the Skulkill. It was not the moment to see it. There was not yet a green leaf. Straightaway I cam upon Bartram, the traveler and poet. . . . he showed us a few trees and bushes, brought for the most part from Georgia and the Carolinas, and the remainder from the Continent. His interest in botany, added to the profits that he has made from it, has led him to undertake, at times, journeys of 100 miles solely to go into a forest to collect there a plant or a bush. Franklinia is a tree from Georgia, with a superb flower; Gotheria procumbens from Jersey with its little leaves of deep green speckled with red; they taste like honey; during the wars it was served instead of tea. The hothouse is neither big nor luxuriant. I have seen there green tea from China and Boh[e]a. Its leaves are a deep green, an inch and a half in length when they are allowed to grow; but for drinking they are picked very young, especially those of Imperial Tea. Bartram deals in plants, flowers, bushes, etc.; he sells much to Europe. He is the best botanist in this country.”

- Wilson, Alexander, August 10, 1804, “A Rural Walk. The Scenery drawn from Nature,” Gray’s Ferry (1876: 359, 361–64)[24]

- “The Summer sun was riding high,

- “The wood in deepest verdure drest;

- “From care and clouds of dust to fly,

- “Across yon bubbling brook I past;

- “And up the hill, with cedars spread,

- “I took the woodland path, that led

- “To Bartram’s hospitable dome . . . .

- “The squirrel chipp’d, the tree-frog whirr’d,

- “The dove bemoan’d in shadiest bow’r . . . .

- “A wide extended waste of wood,

- “Beyond in distant prospect lay;

- “Where Delaware’s majestic flood

- “Shone like the radiant orb of day . . . .

- “There market-maids, in lovely rows,

- “With wallets white, were riding home;

- “And thund’ring gigs, with powder’d beauxs [sic],

- “Through Gray’s green festive shade to roam.

- “There Bacchus fills his flowing cup,

- “There Venus’ lovely train are seen;

- “There lovers sigh, and gluttons sup,

- “But dearer pleasures warm my heart,

- “And fairer scenes salute my eye;

- “As thro’ these cherry-rows I dart

- “Where Bartram’s fairy landscapes lie.

- “Sweet flows the Schuylkill’s winding tide,

- “Where nature sports, in all her pride

- “Of choicest plants, and fruits, and flow’rs.

- “These sheltering pines that shade the path,—

- “That tow'ring cypress moving slow,—

- “Survey a thousand sweets beneath,

- “And smile upon the groves below. . . .

- “From pathless woods, from Indian plains,

- “From shores where exil’d Britons rove;

- “Arabia’s rich luxuriant scene,

- “And Otaheite’s ambrosial grove.

- “Unnumber’d plants and shrubb'ry sweet,

- “Adorning still the circling year;

- “Whose names the Muse can ne’er repeat,

- “Display their mingling blossoms here. . . .

- “For them thro’ Georgia’s sultry clime,

- “And Florida’s sequester’d shore;

- “Their streams, dark woods, and cliffs sublime,

- “His dangerous way he did explore.

- “And here their blooming tribes he tends,

- “And tho’ revolving Winters reign,

- “Still Spring returns him back his friends,

- “His shades and blossom’d bowers again.”

- Bartram, William, 1807, Preface to A Catalogue of Trees, Shrubs, and Herbaceous Plants, Indigenous to the United States of America (1996: 586–87)[25]

- “KINGSESS GARDENS were begun about 80 years since by JOHN BARTRAM the elder. . . . They are situated on the west banks of the Schuylkill, four miles from Philadelphia, and contain about eight acres of land. The mansion and green houses stand on an eminence from which the garden descends by gentle slopes to the edge of the river, and on either side the ground rises into hills of moderate elevation to the summits of which its borders extend. From this scite [sic] are distinctly seen the winding course of the Schuylkill, its broad-spread meadows and cultivated farms, for many miles up and down. . . . The whole comprehends an extensive prospect, rich in the beauty of its scenery and endless in diversity.

- “His [Bartram’s] view in the establishment [of the garden] was to make it a deposite [sic] of the vegetables of these United States, (then British Colonies), as well as those of Europe and other parts of the earth, that they might be the more convenient for investigation. He soon furnished his grounds with the curious and beautiful vegetables in the environs, and by degrees those more distant, which were arranged according to their natural soil and situation, either in the garden, or on his plantation, which consisted of between 200 and 300 acres of land, the whole of which he termed his garden. . . .

- “Thus these extensive gardens became the Seminary of American vegetables, from whence they were distributed to Europe, and other regions of the civilized world. They may with propriety and truth be called the Botanical Academy of Pennsylvania, since, being near Philadelphia, the Professors of Botany, Chemistry, and Materia Medica, attended by their youthful train of pupils, annually assemble here during the Floral season.

- “The revered founder lived to see his garden flourish beyond him most sanguine expectations, and extend its reputation both at home and abroad, as the Botanic Garden of America. In this condition it descended to his son, whose care it has been to preserve its well-earned fame, as well by continuing the collection already there, as by making annual excursions to increase the variety. Finding old age coming on, he has lately associated his son with him in the concern, and hopes by their untied exertions the gardens will continue to be worthy of the attention of the lovers of science and the admirers of nature.”

- Pursh, Frederick, 1814, recalling a visit to Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery in 1799 (1814: 1:vi)[26]

- “Near Philadelphia I found the botanic garden of Messrs. John and William Bartram. This is likewise an old establishment, founded under the patronage of the late Dr. Fothergill, by the father of the now living Bartrams. This place, delightfully situated on the banks of the Delaware, is kept up by the present proprietors, and probably will increase under the care of the son of John Bartram, a young gentleman of classical education, and highly attached to the study of botany. Mr. William Bartram, the well known author of “Travels through North and South Carolina,” I found a very intelligent, agreeable, and communicative gentleman; and from him I received considerable information about the plants of that country, particularly respecting the habitats of a number of rare and interesting trees. It is with the liveliest emotions of pleasure I call to mind the happy hours I spent in this worthy man’s company, during the period I lived in his neighbourhood.

- Baldwin, William, August 14, 1818, letter from Philadelphia to William Darlington (Darlington 1843: 277–78)[27]

- “ I spent several hours yesterday with our worthy old friend BARTRAM; and have made an arrangement with Col. ROBERT CARR, who has the management of the garden, to cultivate my S. American plants. He has now the Lantana Bratrami [sic] (for the first time) in flower in his garden . . . . Mrs. CARR (daughter of the late JOHN BARTRAM,) draws elegantly,—and has engaged to execute as many drawings for me as I want. . . . .

- “I found yesterday . . . a new species of Prunella . . . .On showing a specimen of it to Mr. BARTRAM, he thought he had seen it,—and considered it a new species. He will search for it, and let me know.”

- Thacher, James, 1828, describing history of Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (1828: 1:67)[28]

- “Mr. Bartram was the first native American who conceived and carried into effect the plan of a botanical garden for the reception and cultivation of indigenous as well as exotic plants, and of travelling for the purpose of accomplishing this plan. He purchased a situation on the banks of Schuylkill, and enriched it with every variety of the most curious and beautiful vegetables, collected in his excursions, which his sons have since continued to cultivate.”

- Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1830, describing Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (quoted in Boyd 1929: 428)[29]

- “Mr. Carr’s fruit nursery has been greatly improved, and will be enlarged next spring to twelve acres—its present size is eight. The trees are arranged in systematical order, and the walks well gravelled. The whole is abundantly stocked, from the seed bed to the tree. Here are to be found 113 varieties of apples, 72 of pears, 22 of cherries, 17 of apricots, 45 of plums, 39 of peaches, 5 of nectarines, 3 of almonds, 6 of quinces, 5 of mulberries, 6 of raspberries, 6 of currants, 5 of filberts, 8 of walnuts, 6 of strawberries, and 2 of medlars. The stock, considered according to its growth, has in the first class of ornamental trees, esteemed for their foliage, flowers, or fruit, 76 sorts; of the second class 56 sorts; of the third class 120 sorts; of ornamental evergreens 52 sorts; of vines and creepers, for covering walls and arbours, 35 sorts; of honey suckle 30 sorts, and of roses 80 varieties.”

- Wynne, William, June 1832, “Some Account of the Nursery Gardens and the State of Horticulture in the Neighbourhood of Philadelphia,” describing the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, vicinity of Philadelphia (Gardener’s Magazine 8: 272–73)[30]

- “I shall begin with Bartram’s Botanic Garden; the precedence being due to it, both for antiquity (it having been established 100 years), and from its containing the best collection of American plants in the United States. There are above 2000 species (natives) contained in a space of six acres, not including the fruit nursery and vineyard, which comprise eight acres. . . . Indeed, the most remarkable feature in this nursery, and that which renders it superior to most of its class, is the advantage of possessing large specimens of all the rare American trees and shrubs; which are not only highly ornamental, but likewise very valuable, from the great quantities of seed they afford for exportation to London, Paris, Petersburgh, Calcutta, and several other parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa. This garden is the regular resort of the learned and scientific gentlemen of Philadelphia.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), June 1837, describing Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (Magazine of Horticulture 3: 210)[31]

- “It is with deep regret that we learn that one of the principal rail roads in the State of Pennsylvania, now constructing, will run to the city directly through the nursery of Col. Carr, and will cut up the grounds in such a manner as to entirely destroy their beauty; but what is a source of yet deeper regret, is the destruction which it will cause of some of the old and still beautiful specimens of trees which ornament the place; several of these, which have long served as a memento of the zealous labors of the elder Bartram and his sons, will fall by the woodman’s axe. It is a melancholy scene to the American horticulturist to see the few beautiful private residences and nurseries of which our country can boast, one by one, purchased by individuals or companies, to be cut up into building lots, or otherwise destroyed, by rail roads running directly through them. Dr. Hosack’s, at Hyde Park, N.Y., the best specimens of gardening in this country, was the first; Mr. Pratt’s, Laurel [Lemon] Hill, but little inferior in its style, next; and now one of the oldest nurseries, bounded by one of the best naturalists this country ever produced, is to follow, though not the same, a similar fate.”

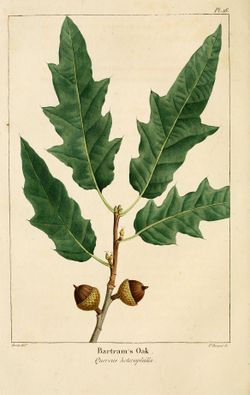

- Michaux, François André, 1841, describing the Bartram Oak at the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (1841: 1:37)[32]

- “Every botanist who has visited different regions of the globe must have remarked certain species of vegetables which are so little multiplied that they seem likely at no distant period to disappear from the earth. To this class belongs the Bartram Oak. Several English and American naturalists who, like my father and myself, have spent years in exploring the United States, and who have obligingly communicated to us the result of their observations, have like us, found no traces of this species except a single stock in a field belonging to Mr. Bartram, on the banks of the Schuylkill, 4 miles from Philadelphia . . . . [Fig. 2]

- “Several young plants, which I received from Mr. Bartram himself, have been placed in our public gardens to insure the preservation of the species.”

- Darlington, William, 1849, describing Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (1849: 18–19)[18]

- “He [John Bartram] was, perhaps, the first Anglo-American who conceived the idea of establishing a BOTANIC GARDEN for the reception and cultivation of the various vegetables, natives of the country, as well as exotics, and of travelling for the discovery and acquisition of them.

- “*The BARTRAM BOTANIC GARDEN, (established in or about the year 1730,) is most eligibly and beautifully situated, on the right bank of the river Schuylkill, a short distance below the city of Philadelphia. Being the oldest establishment of the kind in this western world, and exceedingly interesting, from its history and associations,—one might almost hope, even in this utilitarian age, that, if no motive more commendable could avail, a feeling of state or city pride, would be sufficient to ensure its preservation, in its original character, and for the sake of its original objects. But, alas! there seems to be too much reason to apprehend that it will scarcely survive the immediate family of its noble-hearted founder,—and that even the present generation may live to see the accumulated treasures of a century laid waste—with all the once gay parterres and lovely borders converted into lumberyards and coal-landings.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1850, describing nurseries in America (1850: 339)[33]

- “884. At and near Philadelphia are Bartram’s botanic garden, now the nursery of Colonel Carr, and accurately described by his foreman, Mr. Wynne (Gard. Mag., vol. viii. p. 272.); Messrs. Landreth and Co.’s nursery; and that of Messrs. Hibbert and Buist; besides some commercial gardens in which, to a small nursery with green and hot-houses, are added the appendages of a tavern. These tavern gardens, Mr. Wynne informs us, are the resort of many of the citizens of Philadelphia, more especially the gardens of M. Arran, and M. d’Arras; the first having a very good museum, and the latter a beautiful collection of large orange and lemon trees.”

Images

Map

Other Resources

The Cultural Landscape Foundation

Notes

- ↑ Joel T. Fry, John Bartram’s House and Garden (Bartram’s Garden), Historic American Landscape Survey, (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior. National Park Service, 2004), 4, 7, 15–18, 22, 27–30, view on Zotero, and James A. Jacobs, John Bartram House and Garden, Greenhouse (Seed House), Historic American Landscapes Survey (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior. National Park Service, 2001), 1–2.

- ↑ Fry 2004, 4, 7, 18, 22, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fry 2004, 43, view on Zotero

- ↑ For a discussion, see Therese O’Malley, “Art and Science in the Design of Botanic Gardens, 1730–1830,” in Garden History: Issues and Approaches, ed. John Dixon Hunt (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1992), 282, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Bartram to J. Slingsby Cressy, c. 1740, in John Bartram, The Correspondence of John Bartram, 1734–1777, ed. Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992), 131, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Bartram to Peter Collinson, July 19, 1761, in Bartram 1992: 529, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For examples, see Joel T. Fry, “John Bartram and His Garden: Would John Bartram Recognize His Garden Today?,” in America’s Curious Botanist: A Tercentennial Reappraisal of John Bartram, 1699–1777, ed. Nancy Everill Hoffmann and John C. Van Horne (Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 2004), 159n10, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James A. Jacobs, John Bartram House and Garden, Greenhouse (Seed House), Historic American Landscapes Survey (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior. National Park Service, 2001), 2, 4, view on Zotero.

- ↑ See, for example, Bartram 1992, 495, 529, 668–69, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bartram, William Bartram: Travels and Other Writings, ed. Thomas P. Slaughter (New York: The Library of America, 1996), 587, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fry 2004, 56, view on Zotero, and Benjamin Hays Smith, “Some Letters from William Hamilton of The Woodlands to his Private Secretary,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 29 (1905): 258–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, 5 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1979), 5:166, 183, view on Zotero.

- ↑ See “List of Plants from John Bartram’s Nursery, March 1792,” and George Augustine Washington to George Washington, April 15–16, 1792, in George Washington, The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, ed. Robert F. Haggard and Mark A. Mastromarino (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 2002), 10: 175–83, 272–73, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fry 2004, 5, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.8 Bartram, 1992, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pehr Kalm, Travels into North America . . ., trans. John Reinhold Forster, 3 vols. (London: John Reinhold Forster, 1770), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cadwallader Colden, “The Letters and Papers of Cadwallader Colden,” vol. 4 (1748–1754), Collections of the New-York Historical Society (1920): 471–72, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 William Darlington, Memorials of John Bartram and Humphry Marshall: With Notices of Their Botanical Contemporaries (Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ “A Russian Gentleman, Describing the Visit He Paid at My Request To Mr. John Bertram, The Celebrated Pennsylvanian Botanist,” in J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur, Letters from an American Farmer: Describing Certain Provincial Situations, Manners, and Customs Not Generally Known (London: Thomas Davies and Lockyer Davis, 1783), view on Zotero

- ↑ George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, 5 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1979), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Manasseh Cutler, Life, Journals and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D., ed. William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkin Cutler, 2 vols. (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1888), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Washington, The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, ed. Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, Under Their Vine and Fig Tree: Travels through America in 1797–99, 1805, with Some Further Account of Life in New Jersey, ed. and trans. Metchie J. E. Budka (Elizabeth, NJ: The Grassmann Publishing Company, 1965), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Wilson, The Poems and Literary Prose of Alexander Wilson, the American Ornithologist, ed. Alexander B. Grosart, 2 vols. (Paisley: Alex. Gardner, 1876), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1996, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Pursh, Flora Americae Septentrionalis; Or, a Systematic Arrangement and Description of the Plants of North America, 2 vols. (London: White, Cochrane, & Co., 1814), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Baldwin, Reliquiae Baldwinianae: Selections from the Correspondence of the Late William Baldwin with Occasional Notes, and a Short Biographical Memoir, ed. William Darlington (Philadelphia: Kimber and Sharpless, 1843), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Thacher, American Medical Biography: Or, Memoirs of Eminent Physicians Who Have Flourished in America, 2 vols. (Boston: Richardson & Lord and Cottons & Barnard, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Boyd, A History of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1827–1927 (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1929), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Wynne, “Some Account of the Nursery Gardens and the State of Horticulture in the Neighbourhood of Philadelphia, with Remarks on the Subject of the Emigration of British Gardens to the United States,” Gardener’s Magazine and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 8, no. 38 (June 1832): 272–76, view on Zotero.

- ↑ C. M. Hovey, “Notes on some of the Nurseries and Private Gardens in the neighborhood of New York and Philadelphia, visited in the early part of the month of March, 1837,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 3, no. 6 (June 1837): 201–13, view on Zotero.

- ↑ François André Michaux, The North American Sylva; Or, A Description of the Forest Trees of the United States, Canada, and North America . . ., trans. Augustus L. Hillhouse, 6 vols. (Philadelphia: J. Dobson, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed., corr. and improved (London: Longman et al., 1850), view on Zotero.