Difference between revisions of "Robert Mills"

C-tompkins (talk | contribs) (→Images) |

|||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

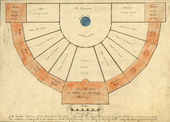

Image:0433.jpg|"Plan of the Washington Canal," 1831. | Image:0433.jpg|"Plan of the Washington Canal," 1831. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0831.jpg|Sketch for a Monument to President Andrew Jackson, c. 1835-40. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1226.jpg|Sketch for a Monument to President Andrew Jackson, c. 1835-40. | ||

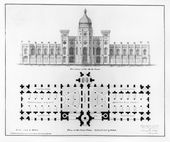

Image:1423.jpg|"Sketch of Plan of the Treasury Building, Extended," 1836-1842, in William H. Pierson, ''American Buildings and Their Architects: The Colonial and Neoclassical Styles'' (1970), p. 405, fig. 291. | Image:1423.jpg|"Sketch of Plan of the Treasury Building, Extended," 1836-1842, in William H. Pierson, ''American Buildings and Their Architects: The Colonial and Neoclassical Styles'' (1970), p. 405, fig. 291. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Image:0033.jpg|"Plan of the Mall," Washington, D.C., 1841. | Image:0033.jpg|"Plan of the Mall," Washington, D.C., 1841. | ||

| Line 91: | Line 93: | ||

Image:1225.jpg|"Projection of the Fire-Proof Buildings for the Navy & War Depts.," c. 1843, in John M. Bryan, ''Robert Mills: America's First Architect'' (2001), p. 249. | Image:1225.jpg|"Projection of the Fire-Proof Buildings for the Navy & War Depts.," c. 1843, in John M. Bryan, ''Robert Mills: America's First Architect'' (2001), p. 249. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Image:1835.jpg|"Sketch of the Washington Nat'l. Monumt.," 1845. | Image:1835.jpg|"Sketch of the Washington Nat'l. Monumt.," 1845. | ||

Revision as of 16:21, May 1, 2015

Robert Mills (August 12, 1781 – March 3, 1855) was an American engineer and architect best known for designing the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C. He was responsible for some of America’s earliest commemorative monuments, as well many public buildings in the nation’s capital and elsewhere. His blend of Palladian, Georgian, and Greek Revival styles contributed to the development of a distinctive Federal mode of architecture.

History

Around 1800, Mills left his native Charleston, South Carolina to work under the architect James Hoban (c.1758-1831) on the President’s House in the city of Washington. There, Mills became acquainted with Thomas Jefferson, who lent him European books on architecture and in 1803 recommended him for a place in the office of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, who was then designing a canal in the vicinity of the future National Mall while also overseeing work at the President’s House and the U.S. Capitol. [1] Both Latrobe’s civil engineering work and his modern interpretation of ancient Greek and Roman architecture had lasting effects on Mills’s career.

In 1814 Mills won an important competition to design the Washington Monument in Baltimore, Maryland, which was to be the first public monument dedicated to the memory of George Washington. In advancing his candidacy, Mills had emphasized his American birth and education, noting that his architectural training had been “altogether American and unmixed with European habits.” [2] Mills’s knowledge of ancient and modern European art and architecture was actually quite extensive, and he drew freely on Old World prototypes in designing his landmark American monument, which ultimately took the form of a colossal Doric column on a cubic base surmounted by a statue of Washington. [3]

The Baltimore commission created opportunities to work on a number of smaller monuments. Mills designed an Egyptian Revival obelisk for the Aquilla Randall Monument (1816-17) in Baltimore and he repeated the obelisk form in subsequent commemorative projects, including the De Kalb (1824-27) and Maxcy Monuments (1824-27) in South Carolina, [4] as well as a drawing he submitted in 1825 for the competition to design the Bunker Hill Monument in Charleston, Massachusetts. Mills’s series of memorial monuments culminated in the most ambitious public monument to honor of George Washington, the Washington Monument on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Mills had proposed a variety of architectural projects in the President’s memory following his move to Washington in 1830, [5] but it was not until 1845 that he secured the commission, and the monument was not completed until 30 years after his death.

From early in his career, Mills had tailored many of his architectural and civil engineering projects to address the need for public recreation, urban green space, and landscape improvement. While serving as president of the Baltimore Water Company (1816-17), he devised a plan for improving the city’s waterways that included tree-lined promenades (with “romantic scenery and cascade/cataract/waterfalls”) for public recreation. [6] The recommendations Mills made for developing canals in South Carolina in the early 1820s included lengthy discussions of the canals’ impact on daily life. [7] In 1831, commissioned to redesign the Washington canal, he expanded his purview to include the entire Mall, which he accommodated to a grid plan—a scheme he revised ten years later when he designed a Botanic Garden and the Smithsonian Institution building on the Mall. [8] Mills’s meticulously detailed 1841 plans conceived of the National Mall as a didactic as well as a recreational space in which specimen plantings were laid out in an assemblage of gardens of contrasting styles, interlinked above ground by pleasantly meandering paths and underground by pipes providing water for irrigation and ornamental fountains. Mills’s designs for the National Mall have been interpreted as “part of an ambition to create a city-wide `museum’ of architecture and taste in Washington.” [9] The National Mall was just one of several architectural and engineering projects that Mills undertook in the nation’s capital, the number and variety of which conferred on him the status of “unofficial federal architect.” [10]

--Robyn Asleson

Texts

- 20 March 1825, in a letter to the Monument Commission, describing plans for the Bunker Hill Monument, Boston, Mass. (quoted in Gallagher 1935: 204–6) [11]

- “I have the honor to submit for your consideration and approval, a design for the Monument you propose erecting on the spot, where the Brave General Warren and his worthy associates fell; to commemorate their valor, and the gratitude of their Country. . . .

- “In the design for the Monument which I now have the honor to lay before you, I would recommend the adoption of the obelisk form, in preference to the Column—the detail I have affixed to this species of pillar, will be found to give it a peculiarly interesting character, embracing originality of effect with simplicity of design, economy in execution, great solidity and capacity for decoration, reaching to the highest degree of splendor consistant with good taste. . . .

- “The obelisk form is, for monuments, of greater antiquity than the Column as appears from history, being used as early as the days of Ramises King of Egypt in the time of the Trojan War—Kercher reckons up 14 obelisk that were celebrated above the rest, namely, that of Alexandria; that of the Barberins; those of Constantinople; of the Mons Esquilinus; of the Campus Flaminius; of Florence; of Heliopolis; of Ludorisco; of St. Makut, of the Medici of the vatican; of M. Coelius, and that of Pamphila. The highest on record mentioned, is that erected by Ptolemy Philadelphus in memory of Arsinoe.

- “The obelisk form is peculiarly adapted to commemorate great transactions from its lofty character, great strength, and furnishing a fine surface for inscriptions — There is a degree of lightness and beauty in it that affords a finer relief to the eye than can be obtained in the regular proportioned Column.

- “Our monument includes a square of 24 feet at the base above the zocle or plinth, and is 15 feet square at the top — Its total elevation is 220 feet above the pavement — The shaft is divided into four great compartments for inscriptive, and other decorations, which come more immediately under the eye by means of oversailing platforms, enclosed by balastrades, supported as it were by winged globes (symbols of immortality peculiarly of a monumental Character).

- “A series of shields band round the foot of the shaft, representing the 13 States, which form’d the Federal union, as principal, having their arms sculptured on their face — A star, on a plain tablet in connection with the former, represents each the other states which now constitute our Union — the whole surmounted by spears and wreathes.

- “A flight of stone steps, or a rising platform, surround the base, from whence the lower inscriptions are read —

- “This is inclosed by a rich bronzed palisade — The entrance into the monument is from this platform, when a flight of stone steps, winding round a pillar, ascends to the top, and communicates with the several platforms. Between the galleries, on each face of the pillar, a wreath, hung on a speer, encircles the letter W, which is otherwise decorated and constitute apertures for lighting the interior of the Monument — over the Last wreath, and near the apex of the obelisk, a great star is placed, emblematic of the glory to which the name of Warren has risen — A tripod crowns the whole and forms the surmounting of the Monument — This tripod is the classic emblem of immortality.” [Fig. 1]

- 1 July 1832, in a letter to Richard Walleck, describing Charlestown, Mass. (quoted in Gallagher 1935: 102) [11]

- “When the Bunker Hill Monument Committee advertised for designs for the Monument, I took a good deal of pains to study one which should do honor to the memory of those worthies it was intended to commemorate, and prove an ornament to the city it was to overlook. I went into some detail on the subject of monuments generally and in sending them two designs, recommended in strong terms the adoption of the Obelisk design, not only from its combining simplicity and economy with grandeur, but as there was already a column of massy proportions erected in Baltimore, we ought not, therefore, to repeat this figure, but construct one of equally imposing figure.”

- c. 1841, in a letter to Robert Dale Owen, describing the proposed Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (Scott, ed., 1990: n.p.) [12]

- "Three spacious avenues (of the city) center within these grounds, which at some future day when improved will form three interesting vistas."

- 23? February 1841, in a letter to Joel R. Poinsett, describing his design for the national Mall, Washington, D.C. (Scott, ed., 1990: n.p.) [12]

- “Agreeably to your requisition to prepare a plan of improvement to that part of the Mall lying between 7th and 12th Street West for a botanic garden . . . I have the honor to submit the following Report....

- "Drawing No. 1 presents a general plan of the entire Mall, including that annexed to the President's house, with the particular improvement proposed of that part intended for the Institution and its objects....[Fig. 2]

- "The relative position of the Capitol, President's House, and other public buildings are laid down, as also the position of the proposed buildings for the Institution; the adjacent streets and avenues are also shown, with the line of the Canal which courses through the City, at the foot of the Capitol hill to the Eastern Branch near the Navy Yard, thus making of the south western section, a complete island....

- “The principle upon which this plan is founded is two fold, one is to provide suitable space for a Botanic garden, the other to provide locations for subjects allied to agriculture, the propagation of useful and ornamental trees native and foreign, the provision of sites for the erection of suitable buildings to accommodate the various subjects to be lectured on and taught in the Institution....

- “The Botanic garden is laid out in the centre fronting and opening to the south. On each side of this the grounds are laid out in serpentine walks and in picturesque divisions forming plats for grouping the various trees to be introduced and creating shady walks for those visiting the establishments....

- "A range of trees is proposed to surround three sides of the square which is intended to be laid open by an iron or other railing, the north side to be enclosed with a high brick wall to serve as a shelter and to secure the various hot houses and other buildings of inferior character."

- “The main building for the Institution is located about 300 feet south of the wall fronting the Botanic garden, from which it is separated by a circular road, in the centre of which is a fountain of water from the basin of which pipes are led underground thro’ the walks of the garden, for irrigating the same at pleasure, the fountains may be supplied from the canal flowing near the north wall of inclosure....[Fig. 3]

- "By means of Groups and vistas of trees, picturesque views may be obtained of the various buildings and other such objects as may be of a monumental character and thus there would be an attraction produced which would draw many of our citizens and strangers to partake of the pleasure of promenading here." [Fig. 4]

Images

- 0868.jpg

The Bunker Hill Monument, obelisk design, n.d., in H.M. Pierce Gallagher, Robert Mills, Architect of the Washington Monument, 1781-1855 (1935), opp. p. 104.

- 1423.jpg

"Sketch of Plan of the Treasury Building, Extended," 1836-1842, in William H. Pierson, American Buildings and Their Architects: The Colonial and Neoclassical Styles (1970), p. 405, fig. 291.

- 1227.jpg

Design for the Patent Office Wings, 1842, in Rhodri Windsor Liscombe, Altogether American: Robert Mills, Architect and Engineer, 1781-1855 (1994), p. 232, fig. 86b.

- 1225.jpg

"Projection of the Fire-Proof Buildings for the Navy & War Depts.," c. 1843, in John M. Bryan, Robert Mills: America's First Architect (2001), p. 249.

References

Notes

- ↑ John M. Bryan, ed. Robert Mills, Architect (Washington, D.C.: American Institute of Architects Press, 1989), 1-8, view on Zotero; John M. Bryan, Robert Mills: America’s First Architect (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001), 6-35, view on Zotero; Rhodri Windsor Liscombe, Altogether American : Robert Mills, Architect and Engineer, 1781-1855 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 3-30, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William D. Hoyt, Jr., “Robert Mills and the Washington Monument in Baltimore [part One],” Maryland Historical Magazine 35 (1940): 153, [1]; J. Jefferson Miller, “The Designs for the Washington Monument in Baltimore,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historian 23, no. 1 (March 1964): 23,view on Zotero; Bryan, 2001, 112, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pamela Scott, “Robert Mills and American Monuments," in Robert Mills, Architect, ed. John M. Bryan (Washington, D.C.: American Institute of Architects Press, 1989), 146-54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bryan, 2006, 99-101; Scott, 2006, 153-54; Bryan, 2001, 139-42, 201-02, view on Zotero

- ↑ Bryan, 2001, 220, view on Zotero; Scott, 1989, 157-58 view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bryan, 2001, 136, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bryan, 2001, 151-54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Scott, 1991, 47, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Therese O'Malley, “‘Your Garden Must Be a Museum to You’: Early American Botanic Gardens,” Huntington Library Quarterly 59, no. 2/3 (1996): 226; see also 222-25, view on Zotero; Scott, 1991, 47-50, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Liscombe, 1994, 163, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 H.M. Pierce Gallagher, Robert Mills, Architect of the Washington Monument, 1781-1855 (New York: Columbia University Press), view on Zotero

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Scott, Pamela, ed. 1990. The Papers of Robert Mills. Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources. view on Zotero