Difference between revisions of "Ferme ornée/Ornamental farm"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

<gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| − | File:0187.jpg| | + | File:0187.jpg|Charles Willson Peale, Mount Clare, south façade and garden, 1775. |

File:0045.jpg|Lester Hoadley Seller, A Reconstruction of [[Charles Willson Peale|Peale's]] Transparent Triumphal [[Arch]], 1783–84. | File:0045.jpg|Lester Hoadley Seller, A Reconstruction of [[Charles Willson Peale|Peale's]] Transparent Triumphal [[Arch]], 1783–84. | ||

Revision as of 16:21, April 7, 2021

(Ornamented farm)

See also: Plantation, Seat

History

The term ornamental farm appeared in English for the first time in Stephen Switzer’s Practical Husbandman (1733), a dissertation about ancient and modern villas, and in French (ferme ornée) in Switzer’s 1742 edition of Ichnographia Rustica.[1] The ornamental farm, or ferme ornée, integrated the pleasure garden, farm lands, and kitchen garden. Although this garden type persisted into the mid-19th century in America, evidence for the use of these specific terms is scarce. These terms are used far more frequently by 20th-century garden historians than they were by Americans in the colonial and early national period. The few citations collected for this study come primarily from Thomas Jefferson and A. J. Downing, perhaps the two most prominent figures in early American garden history.

On his visit to England in 1786, Jefferson and his colleague John Adams visited some celebrated ornamented farms, following Thomas Whateley’s recommendation in Observations on Modern Gardening (1770). Jefferson wrote that the gardens and fields of the ferme ornée at Woburn Farm in Surrey were “all. . . intermixed, the pleasure garden being merely a highly ornamented walk through & round the divisions of the farm & kitchen.”[2] Eight years later Jefferson instructed his overseer at Monticello to lay out the lots “disposing them into a ferme ornée by interspersing occasionally the attributes of a garden.”

Although rarely designated as such, many southern gardens in the 18th century exemplified the ferme ornée as defined by Switzer. A visitor to Westover, on the James River in Virginia, reported that William Byrd II was “engaged in planting a colony of Switzer’s upon the Roanoke,” referring to the ornamental farm ideal with which Switzer is credited.[3] These extensive landholdings often comprised fields, kitchen gardens, orchards, and a pasture next to parterres and walks bordered by shrubbery. In the South, the American additions to this garden type were slave quarters, which were often positioned prominently on the site.

Such a display was in keeping with Joseph Addison’s advice to “make a pretty Landskip of one own Possessions.”[4] Descriptions of these plantations, without using the specific phrase “ferme ornée,” or “ornamented farm,” often paraphrased Switzer or Whately. For example, a 1785 description of Crowfield, William Middleton’s plantation near Charleston, reads that it was a “most desirable abode, where profit and pleasure may be as well combined.”[5] As Whately wrote, the ferme ornée permitted the integration of pleasure and profit in gardening.[6]This sense of the combination of farm and garden was clear in Mary M. Ambler’s 1770 account of the celebrated Mount Clare in Baltimore, where the “whole Plantn seems to be laid out like a garden.”[7] In America, the preferred terms were plantation or farm. Belfield, Charles Willson Peale’s estate in Germantown, Pennsylvania, was a kind of ferme ornée in its integration of highly decorated buildings and gardens and fields. The toolshed, for example, was built to look like a triumphal arch.

The terms “ferme ornée” and “ornamental farm” were revived in the 1840s by A. J. Downing, who saw in this garden type an application for his aesthetics of rural taste. He emphasized the importance of the “agriculturalist” in America, claiming that the farmer was the ideal citizen. In his Architecture of Country Houses (1850), he wrote, “[I]n this country, where every farmer is a proprietor, where a large portion of the farmers are intelligent men, and where farmers are not prevented by anything in their condition or in the institutions of the country, from being among the wisest, the best, and the most honored of our citizens, the wants of the farming class deserve, and should receive the attention to which their character and importance entitle them.”[8] He therefore promoted the ferme ornée as an appropriate expression of this class. In his publications he offered designs for farm buildings such as dairies, barns, dovecotes, stables, and icehouses. He even conceived of a suitable style for the farmhouse of a ferme ornée, which he called the cottage ornée.

—Therese O'Malley

Texts

Usage

- Heely, Joseph, 1777, describing Leasowes, property of William Shenstone, Shropshire, England (1777; repr., 1982: 2:228–30)[9]

- “The Leasowes is to be considered as a farm only, without the least violation of character. . .

- “But the powers of the designer’s taste, were too great to lead him into error, particularly in capital points. . . This, without mentioning any thing more is too great of itself not to declare the excellency of his taste—and in a word, the reputation of the Leasowes for being the most compleat Ferme Ornee that ever was formed, so long as it appears in that character, will never die.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, April 7, 1786, describing Leasowes, property of William Shenstone, Shropshire, England (1944: 113)[10]

- “Leasowes, in Shropshire.— . . . This is not even an ornamented farm—it is only a grazing farm with a path round it, here and there a seat of board, rarely anything better. Architecture has contributed nothing. The obelisk is of brick. Shenstone had but three hundred pounds a year, and ruined himself by what he did to this farm. It is said that he died of the heart-aches which his debts occasioned him. The part next to the road is of red earth, that on the further part grey. The first and second cascades are beautiful. The landscape at number eighteen, and the prospect at thirty-two, are fine. The walk through the wood is umbrageous and pleasing. The whole arch of prospect may be of ninety degrees. Many of the inscriptions are lost.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, February 1, 1808, describing an experimental garden at Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1944: 360)[10]

- “. . . in all the open grounds on both sides of the 3d. & 4th. Roundabouts, lay off lots for the minor articles of husbandry, and for experimental culture, disposing them into a ferme ornée by interspersing occasionally the attributes of a garden.” [Fig. 1]

- Repton, Humphry, 1816, describing a villa estate of the Earl of Coventry, Streatham, England (quoted in Hunt and Willis 1975: 366)[11]

- “The house at Streatham, though surrounded by forty acres of grass land, is not a farm, but a Villa in a garden; for I never have admitted the words Ferme Ornè [sic] into my ideas of taste, any more than a butcher’s shop, or a pigsty, adorned with pea-green and gilding.”

Citations

- Addison, Joseph, June 25, 1712, describing the art of nature (Spectator 2: 286)[12]

- “But why may not a whole Estate be thrown into a kind of Garden by frequent Plantations, that may turn as much to the Profit, as the Pleasure of the Owner? . . . Fields of Corn make a pleasant Prospect, and if the Walks were a little taken care of that lie between them, if the natural Embroidery of the Meadows were helpt and improved by some small Additions of Art, and the several Rows of Hedges set off by Trees and Flowers, that the soil was capable of receiving, a Man might make a pretty Landskip of his own Possessions.”

- Switzer, Stephen, 1742, Ichnographia Rustica (quoted in Brogden 1983: 39)[13]

- “This Taste, so truly useful and delightful as it is, has also for some time been the Practice of the best Genius’s of France, under the Title of La Ferme Ornée. And that Great-Britain is now likely to excel in it, let all those who have seen the Farms and Parks of Abbs-court, Riskins, Dawley-Park, now a doing, with other Places of like Nature declare.”

- Whately, Thomas, 1770, Observations on Modern Gardening (1770; repr., 1982: 177, 181–82)[14]

- “A sense of the propriety of such improvements about a seat, joined to a taste for the more simple delights of the country, probably suggested the idea of an ornamented farm, as the means of bringing every rural circumstance within the verge of a garden. This idea has been partially executed very often; but no where, I believe, so completely, and to such an extent, as at Woburn farm. . .

- “With the beauties which enliven a garden, are every where intermixed many properties of a farm; both the lawns are fed; and the lowing of the herds, the bleating of the sheep, and the tinklings of the bell-wether, resound thro’ all the plantations; even the clucking of poultry is not omitted; for a menagerie of a very simple design is placed near the Gothic building; a small serpentine river is provided for the water-fowl; while the others stray among the flowering shrubs on the banks, or straggle about the neighboring lawn: and the corn-fields are the subjects of every rural employment, which arable land, from seed-time to harvest, can furnish. But though so many of the circumstances occur, the simplicity of a farm is wanting; that idea is lost in such a profusion of ornament; a rusticity of character cannot be preserved amidst all the elegant decorations which may be lavished on a garden.”

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803: 92–94)[15]

- “The French term Ferme ornée, was, I believe, invented by Mr. Shenstone, who was conscious that the English word Farm would not convey the idea which he attempted to realize in the scenery of Leasowes. . .

- “If the yeoman destroys his farm by making what is called a Ferme ornée, he will absurdly sacrifice his income to his pleasure: but the country gentleman can only ornament his place by separating the features of farm and park; they are so totally incongruous as not to admit of any union but at the expence either of beauty or profit. . . .

- “The chief beauty of a park consists in uniform verdure; undulating lines contrasting with each other in variety of forms; trees so grouped as to produce light and shade to display the varied surface of the ground; and an undivided range of pasture. . .

- “The farm, on the contrary, is for ever changing the colour of its surface in motley and discordant hues; it is subdivided by straight lines of fences. The trees can only be ranged in formal rows along the hedges; and these the farmer claims a right to cut, prune, and disfigure.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 1023)[16]

- “7280. The ferme ornée differs from a common farm in having a better dwelling-house, neater approach, and one partly or entirely distinct from that which leads to the offices. It also differs as to the hedges, which are allowed to grow wild and irregular. . . and are bordered on each side by a broad green drive, and sometimes by a gravel-walk and shrubs. It differs from a villa farm in having no park.” [Fig. 2]

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, February 1848, “Hints and Designs for Rustic Buildings” (Horticulturist 2: 363–64)[17]

- “But the more humble and simple cottage grounds, the rural walks of the ferme orneé, and the modest garden of the suburban amateur, have also their ornamental objects and rural buildings—in their place, as charming and spirited as the more artistical embellishments which surround the palladian villa.

- “These are the seats, bowers, grottoes and arbors, of rustic work—than which nothing can be more easily and economically constructed, nor can add more to the rural or picturesque expression of the scene.

- “Those simple buildings, often constructed only of a few logs and twisted limbs of trees, are in good keeping with the simplest or the grandest forms of nature.”

- Downing, A. J., 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1991; repr., 1849: 119–21, 460)[18]

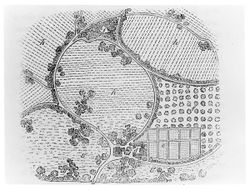

- “The embellished farm (ferme ornée) is a pretty mode of combining something of the beauty of the landscape garden with the utility of the farm, and we hope to see small country seats of this kind become more general. As regards profit in farming, of course, all modes of arranging or distributing land are inferior to simple square fields. . . But we suppose the owner of the small ornamental farm to be one with whom profit is not the first and only consideration, but who desires to unite with it something to gratify his taste, and to give a higher charm to his rural occupations. In Fig. 27, is shown part of an embellished farm, treated in the picturesque style throughout. The various trees, under grass of tillage, are divided and bounded by winding roads, a, bordered by hedges of buckthorn, cedar, and hawthorn, instead of wooden fences; the roads being wide enough to afford a pleasant drive or walk, so as to allow the owner or visitor to enjoy at the same time an agreeable circuit, and a glance at all the various crops and modes of culture. In the plan before us, the approach from the public road is at b; the dwelling at c; the barns and farm-buildings at d; the kitchen garden at e; and the orchard at f. About the house are distributed some groups of trees, and here the fields, g, are kept in grass, and are either mown or pastured. The fields in crops are designated h, on the plan; and a few picturesque groups of trees are planted, or allowed to remain, in these, to keep up the general character of the place. A low dell, or rocky thicket, is situated at i, [sic]. Exceedingly interesting and agreeable effects may be produced, at little cost, in a picturesque farm of this kind. . . The winding lanes traversing the farm need only be graveled near the house, in other portions being left in grass, which will need little care, as it will generally be kept short enough by the passing of men and vehicles over it. [Fig. 3]

- “A picturesque or ornamental farm like this would be an agreeable residence for a gentleman retiring into the country on a small farm, desirous of experimenting for himself with all the new modes of culture. The small and irregular fields would, to him, be rather an advantage, and there would be and air of novelty and interest about the whole residence.

- “On a ferme ornée, where the proprietor desires to give a picturesque appearance to the different appendages of the place, rustic work offers an easy and convenient method of attaining this end. The dairy is sometimes made a detached building, and in this country it may be built of logs in a tasteful manner with a thatched roof; the interior being studded, lathed, and plastered in the usual way. Or the ice-house, which generally shows but a rough gable and ridge roof rising out of the ground, might be covered with a neat structure in rustic work, overgrown with vines, which would give it a pleasing or picturesque air, instead of leaving it, as at present, an unsightly object which we are anxious to conceal.”

- Adams, John, sometime between 1851 and 1856, The Works of John Adams (quoted in Martin 1991: 147–48)[19]

- “It will be long, I hope, before ridings [sic], parks, pleasure grounds, gardens, and ornamental farms, grow so much in fashion in America; but nature has done greater things and furnished nobler material there.”

Images

Inscribed

J. C. Loudon, Plan of a ferme ornée with wild and irregular hedges, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1826), 1023, fig. 722.

Anonymous, “View of a Picturesque farm (ferme ornée),” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), 120, fig. 27.

Associated

Thomas Jefferson, "Plan of Spring Roundabout at Monticello," c. 1804.

Attributed

Samuel McIntire, Design for a Fence, c. 1791.

Charles Willson Peale, View of the Garden at Belfield, 1816.

Notes

- ↑ Robert Holden, “Ferme ornée” entry, The Oxford Companion to Gardens, ed. Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, Susan Jellicoe, Patrick Goode, and Michael Lancaster (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 186, view on Zotero. Also see William A. Brogden, “The Ferme Ornée and Changing Attitudes to Agricultural Improvement,” Eighteenth Century Life 8 (January 1983): 39, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, “Memorandums Made on a Tour to Some of the Gardens in England,” 1786, MS, Swem Library of the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA.

- ↑ George Frederick Frick and Raymond Phineas Stearns, Mark Catesby: Colonial Audubon (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1970), 92, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Addison, [The Art of Nature], Spectator 2, no. 414 (June 25, 1712): 286, view on Zotero.

- ↑ U. P. Hedrick, A History of Horticulture in America to 1860, with an Addendum of Books Published from 1861–1920 (New York: 1950; repr., Portland, OR: Timber Press, 1988), 129, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Whately is discussed in Brogden 1983, 39–40, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Quoted in Barbara Sarudy, “Eighteenth-Century Gardens of the Chesapeake,” Journal of Garden History 9 (July–September 1989): 139, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850; repr., New York: Da Capo Press, 1968), 136, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Heely, Letters on the Beauties of Hagley, Envil, and the Leasowes, 2 vols. (New York: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Dixon Hunt and Peter Willis, eds., The Genius of Place: The English Landscape Garden, 1620–1820 (London: Paul Elek, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Addison, [The Art of Nature], Spectator 2, no. 414 (June 25, 1712), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Brogden 1983, 39–43, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Whately, Observations on Modern Gardening, 3rd ed. (London: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “Hints and Designs for Rustic Buildings,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 2, no. 8 (February 1848): 363–65, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), view on Zotero.