Difference between revisions of "Nursery"

m (CE) |

m (CE) |

||

| Line 155: | Line 155: | ||

*[[Margaret Bayard Smith|Smith, Margaret Bayard]], 1841, describing local nurseries near Washington, DC (1906: 394–95)<ref>Margaret Bayard Smith, ''The First Forty Years of Washington Society'', ed. Gaillard Hunt (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1906), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/FTDFHRFH view on Zotero].</ref> | *[[Margaret Bayard Smith|Smith, Margaret Bayard]], 1841, describing local nurseries near Washington, DC (1906: 394–95)<ref>Margaret Bayard Smith, ''The First Forty Years of Washington Society'', ed. Gaillard Hunt (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1906), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/FTDFHRFH view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | :“There were two '''nursery'''-gardens he [[ [Thomas Jefferson] ]] took particular delight in, partly on account of their romantic and [[picturesque]] location and the beautiful rides that led to them, but chiefly because he discovered in their proprietors, an uncommon degree of scientific information, united with an enthusiastic love of their occupation. . . . Rare fruits and flowers were his [Mr. Mayne’s] pride and delight: this similarity of tastes made [[Thomas Jefferson|Mr. Jefferson]] find peculiar pleasure, in furnishing him with foreign plants and seeds, and in visiting his [[plantation]]s on the high banks of the Potomac.” | + | :“There were two '''nursery'''-gardens he [ [[Thomas Jefferson]] ] took particular delight in, partly on account of their romantic and [[picturesque]] location and the beautiful rides that led to them, but chiefly because he discovered in their proprietors, an uncommon degree of scientific information, united with an enthusiastic love of their occupation. . . . Rare fruits and flowers were his [Mr. Mayne’s] pride and delight: this similarity of tastes made [[Thomas Jefferson|Mr. Jefferson]] find peculiar pleasure, in furnishing him with foreign plants and seeds, and in visiting his [[plantation]]s on the high banks of the Potomac.” |

Revision as of 21:50, June 18, 2018

See also: Bed, Botanic garden, Conservatory, Greenhouse, Hothouse, Orangery

History

Nursery was a term used to describe either the part of a garden where young stock was raised until it could be transplanted to a permanent location or to a business or commercial establishment that sold live plant material. In the first sense, nursery was often used interchangeably with words that have a more specific meaning, such as “seminary” or “botanic garden.” The term “seminary,” which technically refers to a plot where seeds were started, was used to describe the section of a nursery from which plants started from seed were moved to the main part of the nursery. This term was found more often in European and American treatises than in American common usage. In general, the term nursery in America was used to describe a place where plants and seeds alike were cultivated to maturity. George Washington referred to his nursery as a botanic garden, suggesting that this place contained exotic and rare plants, as well as cuttings from mature trees grown elsewhere on his plantation.

General instructions for establishing a nursery included finding a site close to water, in a southeast (rather than full south) orientation, and most importantly, fencing it to keep out animals. Several accounts also emphasized that the soil composition be as close as possible to the plants’ ultimate destination. Nurseries supplied the rest of the garden and also other plantations with every type of plant, ranging from flowers to tall trees.

A nursery generally was laid out with dense plantings in a rectilinear plan that permitted, as John Parkinson said, “plenty of stock in a little space.” Since the nursery had a utilitarian purpose—supplying the garden and filling in vacant spaces—practical considerations, such as the movement of wheelbarrows, were important. According to J. C. Loudon (1826), nurseries in gardens united “the agreeable with the useful,” which was, for him, the object of gardening.

Private and public nurseries were found throughout the colonies from the earliest period and were of critical importance to the settlers. In a 1629 tract for the “unexperienced planter,” Capt. John Smith recommended building nurseries for fruit trees on islands in the Charles River, ensuring that they would be protected from cattle. It was essential at the founding of new settlements to establish as soon as possible those plants and seeds that the colonists brought from Europe. In the Trustees’ Garden founded in 1734 in Savannah, Georgia, oranges, olives, figs, and mulberries—all imported from the Old World—were planted in a public nursery known also as a botanic garden, where planters could get cuttings and scions for free. Gradually, New World species, as well as imported plants, were collected in the nursery and by the 19th century native and exotics were propagated equally. The great private houses of the 18th century had extensive nurseries. At The Woodlands in Philadelphia, owner William Hamilton knew that a garden’s long-term greatness required a nursery first. Beyond the utility of the nursery, several writers, including Loudon and Charles Marshall, extolled the pleasures and satisfaction derived from witnessing the propagation of plants.

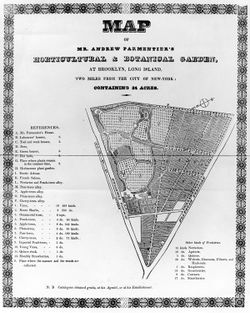

The term “nursery” also referred to commercial firms that sold plants, introduced new plants, and as a result, established a complex trade network.[1] Scholars have attributed the growth of commercial nurseries in the 18th and 19th centuries to a response to both increasing public demand and a wider range of available plants.[2] The commercial nursery business began in America with the activities of importers and growers of domestic horticultural products who participated in the international trade of plants. Recent scholarship has documented a flourishing nursery profession in Boston as early as 1719.[3] The Prince family opened one of the first commercial nurseries in the 1750s.[4] The propagation and cultivation of stock for sale was undertaken quite early in American history. The first catalogues of plants for sale, however, were not published until 1771, when they became available for William Prince’s Linnaean Botanic Garden and Nurseries in Flushing, and then in 1783 for the second generation of the Bartram family, the brothers John and William, who hoped to boost sales at the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, near Philadelphia.[5] In 1792, two large collections of native plants were ordered from the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery for Mount Vernon. After 1800, the first American treatise writers were nurserymen who turned their attention to publishing as a means of promoting their businesses. The work of Bernard M’Mahon, Thomas Green Fessenden, André Parmentier, C. M. Hovey, Robert Buist [Fig. 1], Joseph Breck, Thomas Meehan, and A. J. Downing, to cite some of the most famous, provided the first generation of garden literature in this country. Several of them also used their nurseries as showcases for plants and the newly established profession of landscape design.

After the Revolution, promoters of economic independence for the United States insisted that more nurseries were essential to the new republic.[6] Numerous attempts to establish public nurseries on the national Mall in Washington, DC, document this effort. The 1808 Washington Exposition described a nursery on the national Mall where botanists, agriculturists, and chemists would come together to serve national interests. The White House also was the site of a nursery for trees planted by President John Quincy Adams, who was concerned with the conservation of native hardwoods [Fig. 2]. A speaker at the Massachusetts Horticultural Society in 1830 argued that the country should not be dependent on foreign nurseries. In addition to the nationalistic impulse underlying this talk, other writers knew that the vast range of different soils and climatic conditions available in the United States promised huge economic success. Finally, nurseries were considered important because they gave publicity to new and improved species and, according to George William Johnson (1847), “excite[d] a taste for their cultivation,” thereby stimulating burgeoning botanical, agricultural, and horticultural pursuits.

—Therese O’Malley

Texts

Usage

- Smith, John, 1629, describing the Charles River in Massachusetts (quoted in Miller and Johnson 1963: 2:399)[7]

- “. . . that faire Channell to divide it selfe into so many faire branches as make forty or fifty pleasant Ilands within that excellent Bay. . . . In those Iles, as in the maine, you may make your nurseries for fruits and plants where you put no cattell.”

- Fenwick, George, May 6, 1641, in a letter to Governor John Winthrop, describing his nursery in Saybrook, CT (quoted in Hedrick 1988: 31)[8]

- “I am prettie well storred with chirrie & peach & did hope I had a good nurserie of apples, of the apples you sent me last yeare, but the wormes have in a manner destroyed them all as they came up.”

- Turner, Robert, August 3, 1685, describing a plantation in Pennsylvania (quoted in Blome 1687: 123)[9]

- “A brave Orchard and Nursery have I planted, and they thrive mightily, and bear Fruit the first year.”

- Von Reck, Commissary, 1734, describing the Trustees’ Garden, Savannah, GA (quoted in Marye 1933: 15)[10]

- “There is laid out near the Town, by Order of the Trustees, a Garden for making Experiments for the Improving Botany and Agriculture; it contains 10 Acres and lies upon the River; and it is cleared and brought into such Order that there is already a fine Nursery of Oranges, Olives, white Mulberries, Figs, Peaches, and many curious Herbs.”

- Ball, Joseph, February 1734, describing a property for sale in Virginia (Library of Congress, Joseph Ball Letterbook)

- “The apple Nursery Fence must be kept up right good & strong, but set upon blocks, so that small hogs may go in, to keep down the weeds.”

- Moore, Francis, 1744, describing the Trustees’ Garden, Savannah, GA (quoted in Marye 1933: 15)[10]

- “In the Squares between the Walks were vast Quantities of Mulberry-trees, this being a Nursery for all the Province, and every Planter that desires it, has young Trees given him gratis from this Nursery. These white Mulberry-trees were planted in order to raise Silk.”

- Meade, John, March 26, 1744, describing a nursery in Fairfax County, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “John Meede . . . deeds to Richard Poultney . . . all my Nursery of Young Apple Trees at Twenty shillings.”

- Anonymous, January 30, 1749, describing a plantation for sale near Charleston, SC (South Carolina Gazette)

- “TO BE SOLD at Public Vendue . . . his plantations on the Ashley-River and Wappoo-Creek . . . [with] a very large garden both for pleasure and profit . . . [with] a young nursery with a great number of grafted pear and apple trees of the best sorts, with some thousands of orange trees, some of which are grown 8 feet since the last great frost.”

- Pinckney, Eliza Lucas, 1761, describing Wappoo Plantation, property of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, Charleston, SC (1972: 162)[11]

- “I will endeavor to make amends and not only send the Seeds but plant a nursery here to be sent you in plants at 2 years old.”

- Anonymous, September 21, 1767, describing the Linnaean Botanic Garden and Nurseries, Flushing, NY (quoted in Hedrick 1988: 71)[8]

- “For sale at William Princes nursery, Flushing, a great variety of fruit trees, such as apple, plum, peach, nectarine, cherry, apricot, and pear. They may be put up so as to be sent to Europe.”

- Washington, George, July 13, 1785, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (Jackson and Twohig, eds., 1978: 4:164)[12]

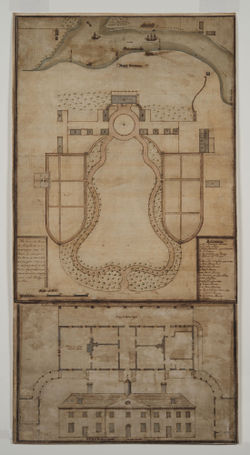

- “Transplanted the Spruce & Fir (or Hemlock) from the Boxes in which they were sent to me by General Lincoln to the Walks by the Garden Gates. The Spare one (Spruce) I placed in my Nursery, or Botanical Garden.” [Fig. 3]

- Hamilton, William, September 30, 1785, in a letter to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia (Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Society Collection)

- “Having observed with attention the nature, variety, & extent of the plantations [in England] of shrubs trees & fruits & consequently admired them, I shall (if God grant me a safe return to my own country) endeavour to make it [[[the Woodlands]]] smile in the same useful & beautiful manner. To take time by the forelock, every person should immediately be made by Mr. Thomson who is on the spot, & I have no doubt you will assist him to the utmost of your power. The first thing to be set about is a good nursery for trees, shrubs, flowers, fruits, &c. of every kind. I do desire that seeds in large quantities may be directly sown of the white flowering locust, the sweet or aromatic birch, the chestnut oak, horse chestnut, chincapins.”

- Bentley, William, October 22, 1790, describing Elias Hasket Derby Farm, Peabody, MA (1962: 1:373)[13]

- “22. . . . [22] By invitation from M’Derby the Clergy spent this afternoon at the Farm in Danvers. . . . We saw whole nurseries of Trees, such as Buttons, fruit trees, & the Mulberry, of the last we had from him the following account. He takes the fruit very ripe, dries it, then pulverises it, & sows it in rows, as other small seed, & it grows above an inch the first year, & in five years, is eight & ten feet high by transplanting. This garden is much improved since I was here last.”

- Strickland, William, September 23, 1794, describing New York, NY (1971: 55)[14]

- “This day was devoted to visiting the nursery gardens in the neighbourhood, in order to procure seeds of whatever was new or curious in the country, to send home. Many of these were already ripe, and collected; and most of the seeds of the trees and shrubs would be so very soon. In one kept by an Old-German of the name of [Jacob] Sperry [in Bowery Lane] exoticks, that is the plants of Europe, were alone cultivated, my purpose therefore was not answered; I could not however but observe that all our shrubs grow to a perfection and luxuriance unknown at home, and many perfect seeds that with us never form them.” [Fig. 4]

- Anonymous, June 14, 1800, describing in the Federal Gazette the estate of Adrian Valeck, Baltimore, MD (quoted in Sarudy 1989: 136)[15]

- “A large garden in the highest state of cultivation, laid out in numerous and convenient walks and squares bordered with espaliers, on which . . . the greatest variety of fruit trees, the choicest fruits from the best nurseries in this country and Europe have been attentively and successfully cultivated . . . Behind the garden in a grove and shrubbery or bosquet planted with a great variety of the finest forest trees, oderiferous & other flowering shrubs etc.”

- Foster, Sir Augustus John, c. 1807, describing Alexandria, VA (quoted in Foster 1954: 162)[16]

- “In passing thro’ Alexandria I visited the nursery garden of Peter Billy, a Frenchman, who had established himself about eight years previously on a piece of common land near the town and in three years produced out of it a very good garden where he cultivated not only fruits and vegetables, but rare American plants. He would ramble about the country and whatever interesting wild flower or shrub he might discover, take it to his garden and try to domesticate it.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, April 17, 1807, describing plans for Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (Jefferson 1944: 334)[17]

- “In the Nursery. began at the N. W. corner & extended rows from N. W. to NE. & planted

- “1st. row abt. 2. f. from the pales} 100. paccans.

- “2d. do. 18 I. from that}

- “3d. do . . . . . . . . Gloucester hiccory nuts from Roanoke.

- “4th. do. do. from Roanoke. 79 in all. 6. do. from Osages. 2. Scarlet beans.

- “5th. a bed of 4. f wide, 3 drills, globe artichoke. red.

- “6th. a do . . . . do . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . green.” [Fig. 5]

- Anonymous, 1808, proposal for the creation of a botanic garden in Washington, DC, published in the Washington Expositor (quoted in O’Malley 1989: 102)[18]

- “Gardens and nurseries capable of receiving and propagating them, where the chemist, botanists, and agriculturalist can have free access at all seasons will it is hoped now become of peculiar interest to the patriot and legislator. . . . Within the limits of the federal seat there are large and ample reservations for public gardens and other national objects, which may advantageously be applied to the purposes of a botanical garden, a public nursery and an agricultural farm.”

- Ramsay, David, 1809, describing Charleston, SC (1858: 128–29)[19]

- “[John] Watson soon after formed a spacious garden for himself on the ground now occupied by Nathaniel Heyward, and afterwards on a large lot of land stretching from King street to and over Meeting street. In the latter he erected the first nursery garden in Carolina. There every new and curious plant that grew or had been naturalized in the country might be purchased. The botanic publications of the day quote him as the introducer of several productions of Carolina to the public gardens in England. By an exchange of such articles, he rendered service to both countries and enriched each with many of the curiosities of the other. These promising attempts at gardening were all laid waste in the revolutionary war. Watson’s garden was revived and continued by himself and descendants after the peace of 1783, but has since gone to ruin.”

- Forman, Martha Ogle, May 1, 1819, describing Rose Hill, home of Martha Ogle Forman, Baltimore County, MD (1976: 102)[20]

- “May 1. . . . We received from Mr. Prince, nursery man in New York, 1 Single Yellow Rose, 1 Weeping Cherry, 1 Black Tarlaman Cherry, 1 White Peace, 1 Green Winter Peach, 11 Algiers Peach, 1 Sickle Pear, 1 Bartlet Pear, 1 St. G Pear all which succeded. 1 large white monthly Rose, 1 yellow and red Austrian Rose, 1 Lemon Clingstone Peach, which died.”

- Prince, Benjamin, and Stephen F. Mills, 1822, describing the Linnaean Botanic Garden and Nursery, Flushing, NY (1822: 3–4)[21]

- “We are often asked, How do you tell one Tree from another. . . . It is almost impossible. Our Nursery is divided into squares; each square into a certain number of rows; we keep as correct a book as any one in the mercantile line, in which each square is recorded, with its boundaries; and each row has its different variety. We commence, for instance, on the west side, the first row, number one, such a kind, and so on through the whole square.”

- Waln, Robert, Jr., 1825, describing the Friends Asylum for the Insane, near Frankford, PA (1825: 232)[22]

- “The nursery contains peaches, apricots, and a number of thriving young trees and shrubs.”

- S., J. W., February 1832, describing André Parmentier’s horticultural and botanical garden, Brooklyn, NY (Gardener’s Magazine 8: 72)[23]

- “In the northern parts of the garden are nurseries, containing young plants of every kind of tree which is to be found in the beds. . . .

- “In short, this establishment is well worthy of notice as one of the few examples in the neighbourhood of New York, of the art of laying out a garden so as to combine the principles of landscape-gardening with the conveniences of the nursery or orchard.” [Fig. 6]

- Wailes, Benjamin L. C., December 26, 1829, describing D. and C. Landreth’s Nursery on Federal Street, Philadelphia (quoted in Moore 1954: 355)[24]

- “Rode out to Landreths Nursery and passed through his hot house [which contained] a number of dwarf Orange & Lemon trees in fruit, a few Camelia, Japonicas in Bloom, a number of young evergreens consisting of the Balm of Gilead, Juniper, Hemlock, Box Arbor Vitae, &c., &c. in hedges & nurseries.” [Fig. 7]

- Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1830, describing Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, vicinity of Philadelphia (quoted in Boyd 1929: 428)[25]

- “Mr. Carr’s fruit nursery has been greatly improved, and will be enlarged next spring to twelve acres—its present size is eight. The trees are arranged in systematical order, and the walks well gravelled. The whole is abundantly stocked, from the seed bed to the tree. Here are to be found 113 varieties of apples, 72 of pears, 22 of cherries, 17 of apricots, 45 of plums, 39 of peaches, 5 of nectarines, 3 of almonds, 6 of quinces, 5 of mulberries, 6 of raspberries, 6 of currants, 5 of filberts, 8 of walnuts, 6 of strawberries, and 2 of medlars. The stock, considered according to its growth, has in the first class of ornamental trees, esteemed for their foliage, flowers, or fruit, 76 sorts; of the second class 56 sorts; of the third class 120 sorts; of ornamental evergreens 52 sorts; of vines and creepers, for covering walls and arbours, 35 sorts; of honey suckle 30 sorts, and of roses 80 varieties.”

- Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1830, describing D. and C. Landreth’s Nursery on Federal Street, Philadelphia (quoted in Boyd 1929: 430)[25]

- “The nursery is all very correctly managed, and covers 40 acres, supplying every part of the union; a detail of which would occupy too much of our space; we therefore content ourselves with stating that the stock is very large, and in every stage of growth, consisting of forest and ornamental trees, shrubs, evergreens, vines and creepers, with a collection of herbaceous plants; fruit trees of the best kind, and most healthy condition, large beds of seedling apples, pears, plums, &c. stocks for budding and grafting; a plan very superior to that of working upon suckers, which carry with them into the graft all the diseases of the parent stock. In these grounds are to be seen in the spring the most beautiful Hyacinths in the country, consisting of 50 different sorts of the double kind. Garden seeds of the finest quality have been scattered over the country from these grounds, and may always be depended upon. The seed establishment of these Horticulturalists is the most extensive in the Union, and its reputation is well sustained from year to year.”

- Dearborn, H. A. S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Harris 1832: 65)[26]

- “On the southeastern and northeastern borders of the tract can be arranged the nurseries.”

- Gordon, Alexander, June 1832, “Notices of some of the principle Nurseries and private Gardens in the United States of America,” describing the nursery of James Bloodgood and Co., vicinity of Flushing, NY (Gardener’s Magazine 8: 280)[27]

- “The extent of their nursery is, I think, about 12 or 15 acres, closely cropped with fruit trees, &c.; and, it being an oblong rectangle, the trees are so arranged that they plough between the rows, from side to side, directly through the different quarters, several times during the summer; thus saving a great deal of manual labour.”

- Wynne, William, June 1832, “Some Account of the Nursery Gardens and the State of Horticulture in the Neighbourhood of Philadelphia,” describing Hibbert Nursery, vicinity of Philadelphia (Gardener’s Magazine 8: 273)[28])

- “A Mr. Hibbert keeps a small nursery, in which he grows roses and other plants in pots, which he sells chiefly in the city market. I understand Mr. Hibbert has taken a piece of ground formerly occupied as a nursery by Mr. M’Mahon, and has taken into partnership Mr. Buist, a gardener in the neighbourhood.”

- Barber, John Warner, and Henry Howe, 1841, describing Browne Mansion House, Flushing, NY (1841: 454)[29]

- “The large and flourishing nursery establishment of Messrs. Parsons & Co. for fruit and ornamental trees, is on this farm.”

- Smith, Margaret Bayard, 1841, describing local nurseries near Washington, DC (1906: 394–95)[30]

- “There were two nursery-gardens he [ Thomas Jefferson ] took particular delight in, partly on account of their romantic and picturesque location and the beautiful rides that led to them, but chiefly because he discovered in their proprietors, an uncommon degree of scientific information, united with an enthusiastic love of their occupation. . . . Rare fruits and flowers were his [Mr. Mayne’s] pride and delight: this similarity of tastes made Mr. Jefferson find peculiar pleasure, in furnishing him with foreign plants and seeds, and in visiting his plantations on the high banks of the Potomac.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), August 1841, “Notes made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, &c.,” describing Downing’s Botanic Garden and Nurseries, Newburgh, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 7: 373)[31]

- “We passed half a day with Mr. Downing in looking through his nursery, and were highly pleased with every part of it. The trees were all very well grown, and the grounds kept clean. The trees are set in rows about four feet apart, and the soil tilled between with the cultivator, and afterwards gone over near the trees with the hoe.”

- Hovey and Co., 1845, describing their nurseries in Cambridge, MA (1845: 3)[32]

- “Our nurseries are very extensive, embracing upwards of thirty acres of land, the whole of which will be devoted to Fruit and Ornamental Trees, Shrubs, Evergreens, Grape Vines, Herbaceous Plants, Dahlias, Bulbous Roots, Greenhouse Plants, &c., &c., Catalogues of which may be had on application.

- “The Nurseries are situated on the Cambridge road to Mount Auburn, half a mile east of Harvard Colleges, and about two miles from Boston. A large conservatory, and an extensive greenhouse, both with span roofs, have been erected, which are filled with choice collections of Camellias, Roses, Pelargoniums, Ericas, Azaleas, and miscellaneous plants. All amateurs and lovers of plants are invited to visit the Nurseries. In the month of May, a splendid collection of Tulips will be in flower;—in June, upwards of four hundred varieties of hardy Roses;—during the autumn, an unrivalled collection of Perpetual, Bourbon, Bengal, Tea, and Noisette Roses;—and in September, a magnificent collection of Dahlias. In the Conservatory, the Chrysanthemums will be in bloom in November—the Camellias in January—the Azaleas in February—the Roses in March, and the Pelargoniums in April and May. Omnibus coaches run within a few rods of the Nurseries every half hour during the day.”

- Londoniensis [pseud.], October 1850, “Notes and Recollections of a Visit to the Nurseries of Messrs. Hovey & Co., Cambridge” (Magazine of Horticulture 16: 445)[33]

- “The fruit department of this nursery, however, is by far the most interesting and extensive that I have yet seen. It occupies upwards of thirty-six acres, and contains upwards of sixty thousand pear trees alone. Now, as you are interested in this department of the business, I will describe the disposition of the ground, and the method of arrangement pursued.

- “In the first place, the nursery is laid out in angular divisions, diverging from a common centre. These divisions are separated from each other by wide walks and avenues, on each side of which is a border some eight or nine feet wide. These borders are planted with specimen trees, inside of which is a border some eight or nine feet wide. These borders are planted with specimen trees, inside of which are the quarters for the nursery stock.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1850, describing nurseries in America (1850: 335, 339)[34]

- “864. Horticulture, Judge Buel observes, received but little attention in the United States until quite a recent period. . . . Four or five public nurseries are all that are recollected of any note, which existed in the United States in 1810, and these were by no means profitable establishments. About the year 1815, a spirit of improvement in horticulture as well as agriculture began to pervade the country, and the sphere of its influence has been enlarging, and the force of example increasing, down to the present time. (Gard. Mag., vol. iv. p. 193.) . . .

- “882. Nursery establishments in America, Mr. Buel observes, are increasing in number, respectability, and patronage. Selections of native fruits are made with better judgement and more care than they formerly were. Most of the esteemed European varieties have been added to our catalogues. The cultivation of indigenous forest trees and shrubs, esteemed for utility, or as ornamental, has been extending; and the study of botany is becoming more general, as well for practical uses as on account of the high intellectual gratification which it affords to the man of leisure or of opulence. . . .

- “883. Near New York is Prince’s Linnaean Garden at Flushing, according to Mr. Buel, the oldest, and according to Mr. Gordon, taking it altogether, one of the best, in the United States. Mr. Stuart says, ‘the variety of magnolias in Prince’s nursery is prodigious.’ In 1840, however, the hothouses and greenhouses belonging to this nursery appear to have been given up, and the plants sold off. There are numerous other nurseries in the neighbourhood, and, among others, that of Messrs. Downing and Co. at Newburgh. In the city are the extensive seed establishments of Messrs. Thorburn and others.

- “884. At and near Philadelphia are Bartram’s botanic garden, now the nursery of Colonel Carr, and accurately described by his foreman, Mr. Wynne (Gard. Mag., vol. viii. p. 272.); Messrs. Landreth and Co.’s nursery; and that of Messrs. Hibbert and Buist; besides some commercial gardens in which, to a small nursery with green and hot-houses, are added the appendages of a tavern. These tavern gardens, Mr. Wynne informs us, are the resort of many of the citizens of Philadelphia, more especially the gardens of M. Arran, and M. d’Arras; the first having a very good museum, and the latter a beautiful collection of large orange and lemon trees.

- “885. Among other nurseries, in different parts of America, are the Albany nursery, at Albany, established by Judge Buel; the Burlington nursery, at New Jersey; Kenrick’s nursery, at Newtown in the vicinity of Boston; the Baltimore nursery; and M. Noisette’s nursery, at Charleston.”

Citations

- Parkinson, John, 1629, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629; repr., 1975: 538)[35]

- Although I know the greater fort (I meane the Nobility and better part of the Gentrie of this Land) doe not intend to keepe a Nursery, to raise up those trees that they meane to plant their wals or Orchards withall, but to buy them already grafted to their hands of them that make their living of it: yet because many Gentlemen and others are much delighted to bestowe their paines in grafting themselves, and esteeme their owne labours and handie worke farre above other mens: for their incouragement and satisfaction, I will here set downe some convenient directions, to enable them to raise an Orchard of all sorts of fruits quickly, both by sowing the kernels or stones of fruit, and by making choice of the best sorts of stockes to graft on: First therefore to begin with Cherries; If you will make a Nursery, wherein you may bee stored with plenty of stockes in a little space.”

- Worlidge, John, 1669, Systema Agriculturae (1669: 88)[36]

- “Make choice of some spare place of ground well Fenced, and secured from Cattel, Conies &c. respecting the South East rather than the full South, and well protected from the North and West.”

- [Chambers, Ephraim, 1743, Cyclopaedia (1743: 2:n.p.)[37]

- “NURSERY, in gardening, denotes a seminary, or seed-plot, for raising young trees, or plants. See SEMINARY.

- “Some authors make a difference between nursery and seminary, holding the former not to be a place wherein plants are sown; but a place for the reception and rearing of young plants, which are removed, or transplanted hither from the seminary, &c. See PLANTING, TRANSPLANTION, &c.

- “Mr. Lawrence recommends the having several nurseries, for the several kinds of trees: One for tall standards; viz. apples, ashes, elms, limes, oaks, pears, sycamores, &c. Another for dwarfs; viz. such as are intended for apricots, cherries, peaches, plumbs, &c. and a third for evergreens. See FRUIT.

- “The nursery for standards should be in a rich, light soil.”

- Miller, Philip, 1754, The Gardeners Dictionary (1754; repr., 1969: 955)[38]

- “NURSERY, or Nursery-garden, is a Piece of Land set apart for the raising and propagating of all Sorts of Trees and Plants, to supply the Garden, and other Plantations.”

- Hale, Thomas, 1757, Eden, or A Compleat Body of Gardening (1757: 2)[39]

- “Some of the hardy Kinds [of plants] may be, and some must be raised where they are to remain; but the greater Part will bear to be transplanted, and some thrive for it the better.

- “These should be raised in another Place, and only brought into the Borders at a proper Time before their flowering.

- “This Consideration gives Origin to what is called the Seminary or Nursery, a distinct Part in the Distribution in the Ground: in this they are to be produced from Seeds or otherwise, and preserved till toward the Time of their arriving at their Perfection.”

- Hale, Thomas, 1758, A Compleat Body of Husbandry (1758: 1:275)[40]

- “This spot design’d for a nursery, must be defended from the north and west, and open to the south east. It must be well fenced: for one breach may destroy the labour of several years, and it will be best if it lie dry.”

- Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce, 1769, The Complete Farmer (1769: n.p.)[41]

- “The Nursery.

- “It is not our intention here to speak of those large and extensive nurseries, where all kinds of plants, trees, and shrubs, are raised for sale; but a nursery that is absolutely necessary for such country gentlemen as are desirous of raising plants, trees, &c. for themselves. Two or three acres of land employed this way may well be sufficient for the most extensive designs; and one acre will be full enough for those of moderate extent. And such a spot of ground may be always employed for sowing the seeds of foreign trees and plants; and also for raising many sorts of biennial and perennial flowers, to transplant into the borders of the pleasure-garden; and for raising many kinds of bulbous-rooted flowers from seeds, whereby a variety of new sorts may be obtained annually, which will sufficiently compensate for the trouble and expence; and, at the same time, afford a very agreeable entertainment to gentlemen who are fond of these innocent amusements.

- “Such a nursery as this should be conveniently situated for water; for where that is wanting, a necessary expence will be incurred by the carriage of it in dry weather. It should also be as near the house as can conveniently be admitted, in order to render it easy to visit it at all times of the year; because it is absolutely necessary that it should be under the inspection of the master, who must delight in it, or there will be very little hopes of success.”

- Deane, Samuel, 1790, The New-England Farmer (1790: 188)[42]

- “NURSERY, a garden, or plantation of young trees to be transplanted.”

- Marshall, Charles, 1799, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening (1799: 1:69–71)[43]

- “THOSE private persons who have the opportunity of ground, and do not mind the expense and trouble of managing a nursery, may find satisfaction and advantages attend it. But there are so many nursery-men ready to supply our wants, that the necessity of a nursery is in a great measure done away; it affords, however, employment, amusement and an opportunity for exercising ingenuity, and that particuarly in the way of graffing.

- “By means of a nursery, trees are ready upon the spot, to be transplanted without damage to the roots from being long out of ground, and the climate and soil being the same in which they are raised and are to grow, and to fruit, there is a sort of certainty of success, that could not otherwise be had. . .

- “A nursery should be laid out into beds of about four feet wide, with alleys of about two; and thus all the work of it will be done conveniently, and the plants will have free air to strengthen them.”

- Bordley, J. B., 1801, Essays and Notes on Husbandry and Rural Affairs (1801: 74–75)[44]

- “The homestead includes this yard; together with its stackyard, the garden, nursery, orchard, and some acres of grass; enough for occasionally letting mares, or sick beasts run on, at liberty.”

- Marshall, William, 1803, On Planting and Rural Ornament (1803: 1:23–26, 34)[45]

- “TREES and SHRUBS may be trained up from the seed bed, &c. until they be fit to be planted out to stand, either in NURSERIES set apart for the purpose, or in YOUNG PLANTATIONS; which last are frequently the most eligible nurseries. . . .

- “THE SITUATION of the nursery is frequently determined by the soil, and frequently by local conveniences: the nearer it is to the garden or seminary, the more attendance will probably be given it; but the nearer it lies to the scene of planting, the less carriage will be requisite. In whatever situation the nursery is placed, it must, like the seminary, be effectually fenced against hares and rabbits. . . .

- “In putting in seedlings. . . . If we say from six to twenty-four inches in the rows, with intervals from one to four feet wide, we shall comprehend the whole variation of distances. . . .

- “We do not recommend planting these nursery plantations too thick; four feet between the rows and two feet between the plants are convenient distances.”

- Nicol, Walter, 1812, The Planter’s Kalendar (1812: 22–23, 25, 129–30)[46]

- “In order to have a complete nursery, it should contain soils of various qualities. . . .

- “The truth is, no part of the nursery should be either too much exposed, or too much sheltered. . . .

- “A nursery should therefore, in general, rise from a level to a pretty smart acclivity; yet no part of it should be too steep, because it is in that case very troublesome to labour.

- “The nursery ground may be sufficiently fenced by a stone-wall, or even a hedge, six feet high; and if it be of small size, an acre, or thereabout, it will require no other shelter; but if it extend to four or five acres, it must have dividing hedges properly situated to afford shelter over all the space. The fence, whether of thorns or stone, should be made proof against the admission of hares or rabbits. . . .

- “The nursery ground should never be encumbered with large trees in the quarters; as apples, pears, or the like; because, being already established in the ground, they never fail to rob the young trees of their food, and to cause them to be poor and stunted, unworthy of being planted in the forest. . .

- “For a Nursery in the above view, no place, certainly, can be more eligible, than a field which may also be occupied as a kitchen garden . . .

- “It is hardly necessary to remark, that in laying out a Nursery, whether simply as such, or as a field garden and nursery combined, it will be proper to have a broad walk, or cartway, to pass through the ground, and perhaps also to cross it, besides the necessary alleys round the fences, and between the quarters, in order that manure may be the more readily carried in, and the crops carried out. This road or walk may be grass; but, if metalled and gravelled, it would give less trouble in keeping.

- “We have observed that the ground should be fenced in such a manner, as to exclude hares and rabbits. With this view, a wall appears to be the most immediate and effectual fence. A small sunk fence, with a hawthorn hedge at top, may answer very well, and may be found advantageous in cases where much draining is requisite.”

- Thacher, James, 1822, The American Orchardist (1822: 30)[47]

- “It is evident, therefore, that the ground to be occupied for a fruit nursery, requires to be made rich and fertile. The soil should also be deep, well pulverized, and cleared of all roots and weeds. The seeds may be sown either in autumn or in April, and in one year after, the young plants may be taken up and replanted in the nursury. It is important that the situation be such as to admit of a free circulation of air, and open to the sun, that the plants may be preserved in a healthy condition.”

- Coxe, William, 1817, A View of the Cultivation of Fruit Trees, and the Management of Orchards and Cider (1817: 13–16)[48]

- “ON THE MANAGEMENT OF A FRUIT NURSERY.

- “The seeds generally used for this purpose, are obtained from the pomace of cider apples—they may be sown in autumn on rich ground, properly prepared by cultivation, and by the destruction of the seeds of weeds, either in broad cast, or in rows, and covered with fine earth; or they may be separated from the pomace, cleaned and dried, and preserved in a tight box or cask to be sown in the spring: the latter mode may be adopted when nurseries are to be established in new or distant situations, the former is more easy and most generally practised.

- “During the first season, the young trees are to be kept free from weeds, and cultivated with the hoe: they will be fit for transplanting the following Spring; or as may sometimes be more convenient, in the Autumn. . . .

- “When removed into the nursery, they should be planted in rows four feet asunder, and about twelve or eighteen inches apart in the rows . . . when young trees have been planted two years, they will be fit for ingrafting in the ground. . . .

- “In four years from the time of planting in the nursery, in a good soil, with good cultivation, the trees will have attained the height of from seven to eight feet; those of vigorous kinds will be taller, and will be fit for transplanting into the orchard.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 451, 973, 974, 1033–34)[49]

- “2355. To unite the agreeable with the useful is an object common to all the departments of gardening. The kitchen-garden, the orchard, the nursery, and the forest, are all intended as scenes of recreation and visual enjoyment, as well as of useful culture; and enjoyment is the avowed object of the flower-garden, shrubbery, and pleasure-ground. . . .

- “6973. Nurseries for rearing trees are commonly left to commercial gardeners, as the plantations of few private landowners are so extensive, or continued through a sufficient number of years to render it worth their while to originate and nurse up their own tree and hedge plants. Exceptions, however, occur in the case of remote situations, and where there are tracts so extensive as to require many years in planting. . . .

- “6982. The principal objects of culture in a private tree-nursery are the hardy trees and shrubs of the country, which produce seeds; and the great object of the private nursery-gardener must be to collect or procure these seeds, prepare them for sowing, sow them in their proper seasons, and transplant and nurse them till fit for final planting. . . .

- “7337. In laying out a nursery. . . . The following seem objects desirable for a complete nursery:

- “7338. The dwellinghouse of the master. . . .

- “7339. A seed-shop. . . .

- “7340. A journeyman’s living-room, and a number of sleeping-rooms for the whole or a part of the journeymen employed by the year. . .

- “7341. A tool-house. . . .

- “7342. A museum and herbarium-room, in which models . . . of all the fruits, and dried specimens of all or most of the plants grown in the nursery, should be kept. . . .

- “7343. Packing-sheds. . . .

- “7344. A stable, cart-shed, cowhouse, and pigsty. . . .

- “7345. A store-ground, or laying-in-ground. . . .

- “7346. A plot for the hot-houses. . . .

- “7347. A compost-ground. . . .

- “7348. A rotting-ground. . . .

- “7349. A parterre. . . .

- “7350. The main area of the nursery should be laid out, as nearly as the circumstances will admit, in parallelograms, of any convenient dimensions, but not wider than the ordinary length of a garden-line.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[50]

- “NURS’ERY, n. . . .

- “2. A place where young trees are propagated for the purpose of being transplanted; a plantation of young trees. Bacon.

- “3. The place where anything is fostered and the growth promoted.”

- Dearborn, H. A. S., September 19, 1829, An Address Delivered Before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (1829: 16)[51]

- “The natural divisions of Horticulture are the Kitchen Garden, Seminary, Nursery, Fruit Trees and Vines, Flowers and Green Houses, the Botanical and Medical Garden, and Landscape, or Picturesque Gardening.”

- Cook, Zebedee, Jr., 1830, An Address, Pronounced Before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (1830: 22–24)[52]

- “Most of the native, and many of the foreign varieties of ornamental trees and shrubs, may be raised from seeds, and a nursery thus formed will in a few years afford a sufficient supply to occupy the borders or other places designed for their reception. . . .

- “We have been too long accustomed to rely upon foreign nurseries for fruit trees and other plants. I am aware that to a certain extent this is unavoidable. But we should depend more upon our own resources, and learn to appreciate them. . . . I would encourage the public nurseries in our own vicinity, not to gratify any exclusive or sectional views, but because we may thereby the more easily avoid the inconveniences which have long been the subject of complaint against others more remote. The fear of prompt and immediate detection and exposure, will have a tendency to render their proprietors more cautious, while the liberal support they would receive, would stimulate them to secure and retain the confidence reposed in them. . . .

- “The public nurseries and gardens of Middlesex and Norfolk are entitled to preeminence among those of New England, and Newton and Brighton, and Charlestown and Milton and Roxbury, are laudably competing with similar establishments in other sections of our country for the general patronage.”

- Hooper, Edward James, 1842, The Practical Farmer, Gardener and Housewife (1842: 266)[53]

- “NURSERY. It has been said, and we think with much good sense, that ‘every farmer ought to raise his own trees,’ because, besides the risk, inconvenience and expense, of bringing our plants from abroad, we have, in pursuing that mode of supply, to encounter the mistakes and the ill consequences which follow a want of analogy between the soil in which the plants were raised, and that to which they are to be transferred. The first step, therefore, towards obtaining a good orchard, is to create a good nursery.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 304, 398)[54]

- “[HORTICULTURE. . . .] ‘One of the greatest impediments to the progress of horticulture in the United States has been the deficiency of nurseries, both as to number and extent. They are not only requisite for furnishing the various kinds of trees and plants which are demanded for utility and embellishment, but to give publicity to the most valuable and interesting species, as well as to excite a taste for their cultivation. These establishments, however, have been much increased and improved within a few years, and there are several in the vicinity of Boston, New York, Albany, Philadelphia, and in the district of Columbia, which are highly creditable to the proprietors and to the country.’—Encyc. Am.”

- “NURSERY is a garden or portion of a garden devoted to the rearing of trees and shrubs during their early stages of growth, before they are of a size desired for the fruit or pleasure grounds.”

Images

Inscribed

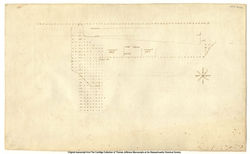

Thomas Jefferson, Plan of an orchard at Monticello, c. 1778. “Nursery” is inscribed at the top right.

Anonymous, “Principal Floor” of a Symmetrical Stone Farm House, in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. 145, fig. 59.

Associated

Samuel Vaughan, Plan of Mount Vernon, 1787.

Attributed

<gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7">

File:0281.jpg|Ralph Earl, Jared Lane, 1796.

File:0112.jpg|Anthony St. John Baker, “View of the White House,” 1826, from Mémoires d’un voyageur qui se repose (1850). The nursery is located in the left foreground, enclosed by a fence.

Notes

- ↑ John Harvey, The Nursery Garden (London: Museum of London, 1990), view on Zotero.

- ↑ P. J. Jarvis, “Plant Introductions to England and Their Role in Horticultural and Sylvicultural Innovation, 1500–1900,” in Change in the Countryside: Essays on Rural England, 1500–1900, eds. H. S. A. Fox and R. A. Butlin (London: Institute of British Geographers, 1979), 145–64, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter Benes, “Horticultural Importers and Nurserymen in Boston 1719–1770,” in Plants and People: Annual Proceedings of the Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife, 1995, ed. Peter Benes (Boston: Boston University, 1996), 38–53, view on Zotero.

- ↑ D. J. and Alan Fusonie, “The Prince Family Nursery: Entrepreneurship Abroad and in New England prior to 1850,” in Benes 1996, 54–65, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joel T. Fry, “An International Catalogue of North American Trees and Shrubs: The Bartram Broadside, 1783,” Journal of Garden History 16, no. 1 (January–March 1996): 3–22, view on Zotero.

- ↑ See Therese O’Malley, “‘Your garden must be a museum to you’: Early American Botanical Gardens,” in Art and Science in America: Issues of Representation, ed. Amy R. W. Meyers (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1998), 35–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Perry Miller and Thomas H. Johnson, eds., The Puritans, 2 vols. (New York: Harper and Row, 1963), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 U. P. Hedrick, A History of Horticulture in America to 1860; with an Addendum of Books Published from 1861–1920 (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Blome, The Present State of His Majesties Isles and Territories in America (London: H. Clark, 1687), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Florence (Nisbet) Marye and Philip Thornton Marye, Garden History of Georgia, 1733–1933, eds. Hattie C. Rainwater and Loraine M. Cooney (Atlanta: Peachtree Garden Club, 1933), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Eliza Lucas Pinckney, The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 1739–1762, ed. Elise Pinckney (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, 6 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1978), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bentley, The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Strickland, Journal of a Tour in the United States of America, 1794–1795, ed. J. E. Strickland (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1971), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Barbara Wells Sarudy, “Eighteenth-Century Gardens of the Chesapeake,” Journal of Garden History 9 (1989): 104–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sir Augustus John Foster, Jeffersonian America: Notes on the United States of America Collected in the Years 1805–1806–1807 and 1811–1812, ed. Richard Beale Davis (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1954), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ann. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), view on Zotero.

- ↑ O’Malley, “Art and Science in American Landscape Architecture: The National Mall, Washington, DC 1791–1852” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1989), view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Ramsay, Ramsay’s History of South Carolina, from Its First Settlement in 1670 to the Year 1808 (Newberry, SC: W. J. Duffie, 1858), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Martha Ogle Forman, Plantation Life at Rose Hill: The Diaries of Martha Ogle Forman, 1814–1845 (Wilmington: Historical Society of Delaware, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Prince and Stephen F. Mills, Treatise and Catalogue of Fruit and Ornamental Trees and Shrubs &c. Cultivated at the Old American Nursery, Flushing Landing, Near New York (New York: Prince and Mills, 1822), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Waln Jr., “An Account of the Asylum for the Insane, Established by the Society of Friends, near Frankford, in the Vicinity of Philadelphia,” Philadelphia Journal of the Medical and Physical Sciences 1 (1825): 225–51, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. W. S., “Foreign Notices: North America,” Gardener’s Magazine and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 8, no. 36 (February 1832): 70–77, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Hebron Moore, “A View of Philadelphia in 1829: Selections from the Journal of B. L. C. Wailes of Natchez,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 78 (July 1954): 353–60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 James Boyd, A History of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1827–1927 (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1929), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thaddeus William Harris, A Discourse Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on the Celebration of Its Fourth Anniversary, October 3, 1832 (Cambridge, MA: E. W. Metcalf, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Gordon, “Notices of Some of the Principal Nurseries and Private Gardens in the United States of America, Made during a Tour through the Country, in the Summer of 1831; with Some Hints on Emigration,” Gardener’s Magazine and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 8, no. 38 (June 1832): 277–89, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Wynne, “Some Account of the Nursery Gardens and the State of Horticulture in the Neighbourhood of Philadelphia, with Remarks on the Subject of the Emigration of British Gardens to the United States,” The Gardener’s Magazine and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 8, no. 38 (June 1832): 272–76, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Warner Barber and Henry Howe, Historical Collections of the State of New York . . . with Geographical Descriptions of Every Township in the State (New York: S. Tuttle, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, ed. Gaillard Hunt (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1906), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes Made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and Intermediate Places, from August 8th to the 23rd, 1841,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 7, no. 11 (November 1841): 361–74, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hovey and Co., Hovey and Co.’s Descriptive Catalogue of a Choice Collection of Flower Seeds (Boston: Hovey, 1845), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Londoniensis [pseud.], “Notes and Recollections of a Visit to the Nurseries of Messrs. Hovey & Co., Cambridge,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 16, no. 10 (October 1850): 442–47, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, new ed. (London: Longman et al., 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1628; repr., Norwood, NJ: W.J. Johnson, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Worlidge, Systema Agriculturae, The Mystery of Husbandry Discovered (London: T. Johnson, 1669), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences . . ., 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1743), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Philip Miller, The Gardeners Dictionary (1754; repr., New York: Verlag Von J. Cramer, 1969), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Hale, Eden, or A Compleat Body of Gardening (London: T. Osborne et al., 1756), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Hale, A Compleat Body of Husbandry Containing Rules for Performing, in the Most Profitable Manner, the Whole Business of the Farmer and Country Gentleman, 2nd ed., 4 vols. (London: T. Osborne, 1758), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce, The Complete Farmer, or A General Dictionary of Husbandry, 2nd ed. (London: R. Baldwin et al., 1769), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Deane, The New-England Farmer, or Georgical Dictionary (Worcester, MA: Isaiah Thomas, 1790), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Marshall, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening, 1st American ed., 2 vols. (Boston: Samuel Etheridge, 1799), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. B. [John Beale] Bordley, Essays and Notes on Husbandry and Rural Affairs, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1801), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Marshall, On Planting and Rural Ornament: A Practical Treatise . . ., 2 vols. (London: G. and W. Nicol, G. and J. Robinson, T. Cadell, and W. Davies, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter Nicol, The Planter’s Kalendar (Edinburgh: D. Willison for A. Constable, 1812), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Thacher, The American Orchardist; Or, A Practical Treatise on the Culture and Management of Apple and Other Fruit Trees . . . (Boston: Joseph W. Ingraham, 1822), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Coxe, A View of the Cultivation of Fruit Trees, and the Management of Orchards and Cider (Philadelphia: M. Careyard, 1817), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ H. A. S. (Henry Alexander Scammell) Dearborn, An Address Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (Boston: J. T. Buckingham, 1833), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Zebedee Cook Jr., An Address, Pronounced before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (Boston: Isaac R. Butts, 1830), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward James Hooper, The Practical Farmer, Gardener and Housewife, or Dictionary of Agriculture, Horticulture, and Domestic Economy (Cincinnati, OH: George Conclin, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.