Beehive

(Apiary, Bee-hive, Beehouse, Bee shed, Hive)

History

Although a variety of terms for beekeeping structures and containers exist in treatises and dictionaries, the terms beehive and bee house predominated in American discourse. Bee shed (in a 1768 deed) and apiary (in an 1831 article in the New England Farmer), however, were also occasionally used. Bee skeps, or beehives made of straw, wicker, or wood baskets, were listed in household inventories in German-settled areas of Pennsylvania, where ryestraw skeps continue to be made today.[1] No American usage examples are known of Noah Webster's term “bee garden,” which he borrowed in 1828 from Samuel Johnson (1755). The distinction between a beehive or skep and a bee house is fairly clear: the former was a hollow vessel of natural or artificial construction for the habitation of bees, while the latter was a structure built by humans for containing bees in one or more hives.

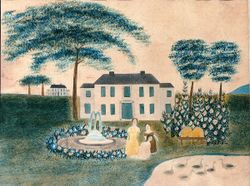

Beehives and houses have been relatively scarce in the archaeological record and were rarely noted in artifact inventories of historic sites because they were composed of perishable materials and they utilized designs that were not earth-fast. Limited evidence of the construction, shape, and placement of beehives in America is provided by a few images of beekeeping containers [Figs. 1–3], as well as by several descriptions. Hives were often depicted as being conical in shape and resting on wooden frames or platforms [Fig. 4]. They appear to have employed coiled construction, and they likely were made of woven or braided straw. J. C. Loudon's 1826 treatise describes several variants of this braided straw form [Fig. 5]. The construction of wood, bark, thatch, or brick bee houses on raised posts was, at least according to 1833 and 1835 articles in the New England Farmer and Loudon’s The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion (1838), an early 19th-century invention. However, citations such as a carpenter’s bill from Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1733 suggest a much longer tradition of this form in America.[2] The moveable frame hive that enabled the large-scale commercial production of honey was not invented until 1860 by Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth. Other forms of hives, such as straw skeps, wooden boxes, and logs, generally required killing the bees and often destroying the hive when harvesting honey.

Beekeeping structures generally figured more prominently in husbandry texts rather than in garden treatises. The first American periodical devoted to bees was Bee Culture, begun in the 1870s, but before then beekeeping articles were published in agricultural journals such as The Genessee Farmer and The American Agriculturalist. One of the first American treatises on beekeeping was John Searle’s New and Improved Mode of Constructing Bee-Houses and Bee-Hives (1839). One of the most popular treatises devoted exclusively to beekeeping was Langstroth on the Hive and the Honey-Bee, A Bee-Keeper’s Manual (1853), which was published in numerous editions and translated into several languages.[3]

In spite of the scarcity of extant physical evidence, beehives and houses are significant to the history of American landscape design in several ways. First, because of the symbiotic relationship between bees’ honey production and their pollination of flowering plants and trees, beehives were often located in orchards or in or near gardens, as at Charles Willson Peale's Belfield estate in Germantown, Pennsylvania. Second, like other utilitarian outbuildings located near dwellings on farms and plantations, beehouses were sometimes ornamented, as with the Gothic bee house described by Martha Trumbull Silliman at Monte Video in Connecticut. Third, bees were categorized in garden treatises and other literature as social creatures, and their presence in the garden connoted various symbolic meanings. The busy creatures’ “work ethic,” described by Jane Loudon (1845) as communicating “particular impressions of industry and usefulness,” was part of their appeal. John Cosens Ogden’s 1800 reference to bees’ “labors” and the repeated motif of hives in didactic art forms such as samplers suggested their association with industry and community. As Jane Loudon also pointed out, the bees’ hum and activity also brought a sense of animation to a garden. Finally, hives produced valuable resources. Fresh honey was used as a sweetener for making mead and as an agricultural commodity.[4] and beeswax was used for candles and was also employed as a finish on furniture.[5]

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Anonymous, 1733, in the Queen Anne’s County Deed Book, describing payment made to a carpenter in Williamsburg, VA (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 31)[6]

- “[The carpenter was paid for] plank & Work Done about the Beehouse. . .”

- Anonymous, 1768, in the Queen Anne’s County Deed Book, describing a farm in Queen Anne’s County, MD (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 31)[6]

- “. . . one bee shed 10 feet by 5.”

- Faris, William, 1793, describing a beehive (quoted in Sarudy 1989: 146–47)[7]

- “[A neighbor] Made Me a present of a Hive of Bees. . .

- “Put the frame of the bee house together drove the Bees out of the old Hive into another and took the honey, the Hive was Rotten and Ready to tumble to pces.”

- Ogden, John Cosens, 1800, describing Bethlehem, PA (1800: 19)[8]

- “On the edge of the hill retired from the town, was a very large collection of bee-hives, in a convenient situation, removed from the neighbourhood of passengers, and amidst an extensive range for their labors.”

- Anonymous, May 9, 1806, describing in the Virginia Herald a property for sale in Orange County, VA (Colonial Willamsburg Foundation)

- “Valuable property for sale! the improvements equal to any in the upper part of the country, there being all convenient houses from a Bee House to two good Dwelling Houses.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, July 29, 1810, in letter to his son, Rembrandt Peale, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:56)[9]

- “. . . & beneath rose bushes, [along the stone wall] you may discover a long Roof which has shelves for Bee hives conveniently situated to get their food from the flowers of the Garden.”

- Silliman, Martha Trumbull, September 1, 1821, describing Monte Video, property of Daniel Wadsworth, Avon, CT (quoted in Saunders and Raye 1981: 20)[10]

- “The place is a great deal handsomer than I expected. The buildings are all Gothic. First there is Uncles beautiful house; 2d the tower, 3d the cottage & the barns 4th the boat house & 5th the bathing house 6th a grape house 7th an ice house & 8th the bee house & a Gothic gate.”

- Anonymous, July 27, 1831, “Bees” (New England Farmer 10: 10)[11]

- “We were recently called to examine a Bee house, or Apiary constructed on this principle by Mr. Munch of Putnam. It is closely covered and lined by unplaned, though jointed boards, to defend its inhabitants from the extremes of heat and cold, and divided by partitions into five chambers supported by posts about 2 1/2 feet from the ground and about 4 feet square, and as many in height.”

- Anonymous, September 25, 1833, “Bee House” (New England Farmer 12: 84)[12]

- “We have seen a bee house, the method of constructing which was introduced into our country by Mr. Eber Wilcox of Salem, and which is said to be a very valuable improvement. Several individuals have tried it with entire success. It consists of a house of brick or wood, (if wood standing on stakes,) say of the size of a common smokehouse, with a door to admit of the entrance of a man. The inside is merely furnished with shelves like an ordinary pantry.”

- Anonymous, June 10, 1835, “Bee and Bee Houses” (New England Farmer 13: 378)[13]

- “The use of houses for bees, we believe, is of modern date. Some three or four winters ago, in travelling in Otsego county, we were shown the first bee-house we ever saw or heard of. One was four, and another six feet square, and six or seven feet high, made perfectly tight, with a good floor, and with a door for occasional entrance. One had been tenanted two summers and contained probably about 200 lbs. honey.”

- Miller, Lewis, 1840s, describing the Geiger Farm, Windsor Township, PA (1966: 75)[14]

- “I Paid A visit to the Three Brothers. . . [They] farm a few Acres of land and have A fine garden, and Orchard of All kind of good fruit trees, and a Stand of Beehives where Bees are kept for the Honey, and to make A little money.”

- Anonymous, January 1853, “A Visit to the House and Garden of the LateA. J. Downing” (Horticulturist 8: 24)[15]

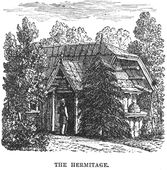

- “The Hermitage is a pretty, rural structure, neatly constructed of rough bark and logs, presenting an attractive object in the walk, and furnishing a cool retreat from the burning heat of our midsummer noons. At one end you may see the bee-hives homes of the little ‘singing masons building roofs of gold,’ who find their favorite food of lemon thyme covering the rocks near by.” [See Fig. 4]

Citations

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741, Cyclopaedia (1741: 1:n.p.)[16]

- “APIARY*, bee-house; a place where bees are kept; and furnished with all the apparatus necessary for that purpose. See BEE, HIVE, BOX. &c.

- “*The word comes from the Latin, apis, a bee. The apiary should be skreened from high winds on every side, either naturally or artificially; and well defended from poultry, &c. whose dung is offensive to bees. See GARDEN, HONEY &c.”

- Parkinson, Richard, 1789–1800, A Tour in America, 1798, 1799, and 1800 (quoted in Sarudy 1989: 147)[7]

- “Honey-bees are kept in America with equal success as in England. . . I never saw a hive made of straw.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 341–42, 801–2)[17]

- “1733. The care of bees seems more naturally to belong to gardening than the keeping of ice; because their situation is naturally in the garden, and their produce is a vegetable salt. The garden-bee is found in a wild state in most parts of the globe, in swarms or governments; but never in groups of governments so near together as in a bee-house, which is an artificial and unnatural contrivance to save trouble, and injurious to the insect directly as the number placed together. . . Hence, independently of other considerations, one disadvantage of congregating hives in bee-houses or apiaries. The advantages are, greater facility in protecting from heats, colds, or thieves, and greater facilities of examining their condition and progress. Independently of their honey, bees are considered as useful in gardens, by aiding in the impregnation of flowers. For this purpose, a hive is sometimes placed in a cherry-house, and sometimes in peach-houses; or the position of the hive is in the front or end wall of such houses, so as the body of the hive may be half in the house and half in the wall, with two outlets for the bees, one into the house, and the other into the open air. By this arrangement, the bees can be admitted to the house and open air alternately, and excluded from either at pleasure. . .

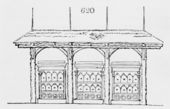

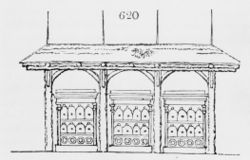

- “1734. The apiary, or bee-house. . . The simplest form of a bee-house consists of a few shelves in a recess of a wall or other building exposed to the south, and with or without shutters, to exclude the sun in summer, and, in part, the frost in winter. The scientific or experimental bee-house is a detached building of boards, differing from the former in having doors behind, which may be opened at any time during day to inspect the hives. . . Bee-houses may always be rendered agreeable, and often ornamental objects: they are particularly suitable for flower-gardens; and one may occur in a recess in a wood or copse, accompanied by a picturesque cottage and flower-garden. They enliven a kitchen-garden, and communicate particular impressions of industry and usefulness. . . [Fig. 6]

- “6127. Decorations. Even the apiary and aviary, or, at least, here and there a beehive, or a cage suspended from a tree, will form very appropriate ornaments.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 1:n.p.)[18]

- “BEE'-GARDEN, n. [bee and garden.] A garden, or inclosure to set bee-hives in. Johnson.”

- Loudon, J. C., 1838, The Suburban Gardener (1838: 713–14)[19]

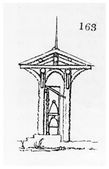

- “The Apiary is another source of interest to all who live in the country, and fortunately it may be indulged in by the humblest labourer, no less than by the wealthiest citizen, provided there are fields and gardens in the neighbourhood containing flowers. A beehive, when there is not room for it any where else, may, like a pigeon-house, or even a garden of pots, be placed on the roof of the house. Much has been, and continues to be, written on the subject of bees; and the kinds of hives are proportionately numerous. Instead of pointing out what we consider to be the merits and defects of the principal of these, we shall limit ourselves to observing that, where little or no attention can be paid to the bees, except perhaps at the swarming season, the common hive of the country, whatever that may be, for example the straw hive in Britain and on the Continent generally, the trunk or pipe hive in Poland, and the cork hive in Spain and the Canaries, will in our opinion be found the best, because every body understands it; but that, where there is leisure, and a disposition to attend to bee culture, Nutt’s hives are by far the best that have been yet invented. It has been a great object with the inventors of hives to devise means for taking the honey without killing the bees; and Mr. Nutt not only effects this, but what is of incomparably more importance, he prevents young bees from being generated, except when they are wanted, and consequently prevents swarming with all its attendant troubles. The principle upon which all Mr. Nutt’s improvements are founded, is that of regulating the temperature of the hives, so that the bees may breed in one temperature, and make their honey in another. Under a certain degree of heat, the queen bee will not lay eggs, nor will these eggs be hatched; while the process of collecting and storing up honey goes on without much reference to temperature, provided the sun shines. Nutt’s hive requires to be placed under some description of cover or bee-house. . . This should, in general, be so contrived as to leave free access to the hive behind, and hence it can never be placed against a wall or against a house. It may be in a detached building, consisting of a rustic structure covered with bark; or it may be placed under a roof open on every side, the props being rustic pillars, and the roof being covered with thatch, reeds, woodman’s chips, spray, bark, health, or similar materials. Fig. 306. Shows a handsome bee-canopy of this kind, covering one of Nutt’s hives, which stands in a recess in the pleasure-ground at Chipstead Place, in Kent. At Bayswater, our Nutt’s hive is placed in the front of a veranda (see fig. 307), in a line with its pillars, and is consequently protected from perpendicular rain; but as the excessive heat of summer is equally injurious with rain, it is protected from that, and from the sudden influence of either heat or cold in winter, by a casing of broom and heath. The back of the hive, where the doors are, on opening which the bees may be seen at work, is most conveniently examined from the veranda.” [Figs. 7 and 8]

Images

Inscribed

J. C. Loudon, Beehive, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), p. 344, fig. 295.

J. C. Loudon, A bee-canopy covering one of Mr. Nutt’s hives, in The Suburban Gardener (1838), p. 713, fig. 306.

J. C. Loudon, "Nutt’s hive is placed in the front of a veranda", in The Suburban Gardener (1838), p. 714, fig. 307.

Associated

J. C. Loudon, “The apiary, or bee-house,” in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1834), p. 613, fig. 620.

Attributed

Harriet De (?), The Duck Pond, c. 1820.

J. C. Loudon, Rustic shed, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1834), p. 227, fig. 163.

Notes

- ↑ William Woys Weaver, personal communication, 1996.

- ↑ Joseph J. Godla, “The Use of Wax Finishes on Pre-Industrial American Furniture” (master’s thesis, Antioch University, 1990), 13, view on Zotero.

- ↑ See John Searle, New and Improved Mode of Constructing Bee-Houses and Bee-Hives (Concord, NH: Asa McFarland, 1839), view on Zotero; and Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth’s Langstroth on the Hive and the Honey-Bee, A Bee-Keeper’s Manual (Northampton, MA: Hopkins, Bridgman, 1853), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lester Breininger, “Beekeeping and Bee Lore in Pennsylvania,” Pennsylvania Folklife 16, no. 1 (spring 1966): 34, view on Zotero; J. Wilmer Pancoast, “History of Bee Culture,” A Collection of Papers Read before the Bucks County Historical Society 3 (1909): 571–78, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For a fuller discussion, see Godla, “The Use of Wax Finishes,” view on Zotero.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Barbara Wells Sarudy, “Eighteenth-Century Gardens of the Chesapeake,” Journal of Garden History 9, no. 3 (July–September 1989): 104–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John C. Ogden, An Excursion into Bethlehem & Nazareth, in Pennsylvania, in the Year 1799 (Philadelphia: Charles Cist, 1800), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 3, The Belfield Farm Years, 1810–1820 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1983–2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Saunders and Helen Raye, Daniel Wadsworth, Patron of the Arts (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1981), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Bees,” New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal 10, no. 2 (July 27, 1831): 10, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Bee House,” New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal 12, no. 11 (September 25, 1833): 84, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Bee and Bee House,” New England Farmer, and Gardener’s Journal 13, no. 48 (June 10, 1835): 378, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lewis Miller, Lewis Miller Sketches and Chronicles: The Reflections of a Nineteenth Century Pennsylvania German Folk Artist (York, PA: Historical Society of York County, 1966), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “A Visit to the House and Garden of the Late A. J. Downing,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 8 (new series 3), no. 1 (January 1853): 21–27, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences . . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter: 1741–43), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion (London: Longman et al., 1838), view on Zotero.