Difference between revisions of "Thicket"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

|||

| (60 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

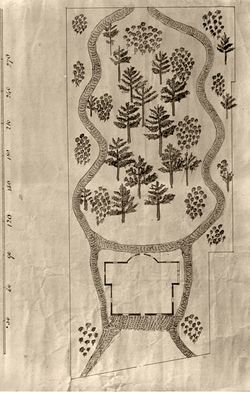

| + | [[File:0002.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 1, Anonymous, Surveyor’s plat of the courthouse and adjacent land Charles County, MD, 1697. The trees in the lower part of the image are labeled “Thickett” on the right edge.]] | ||

| + | Although thicket is not mentioned as frequently as other planting terms in 18th- and 19th-century garden literature, it is nonetheless significant as a description for naturally occurring and designed features [Fig. 1]. According to Thomas Whately, whose 1770 definition was quoted or paraphrased by garden writers for the next century, a thicket was a dense planting of [[wood]]s underplanted with shrubs, akin to a closed [[clump]] or copse. British treatise author Charles Marshall (1799) used “coppice” synonymously with “thicket.” American writers such as [[Bernard M’Mahon]] (1806) offered similar definitions, describing a thicket as closely planted trees with shrubs. It was distinguished from a [[clump]], [[copse]], or [[wood]] by its compactness and smaller scale. | ||

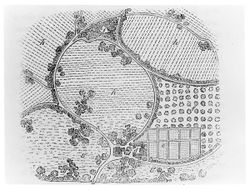

| − | + | This connotation was found in American accounts written by [[Eliza Lucas Pinckney]] (1743), [[Manasseh Cutler]] (1787 and 1802), and [[Thomas Jefferson]] (1806). A more detailed portrayal of thicket was provided by Jefferson in a letter of 1804. In this document, he indicated which plants to include in the thicket, such as azaleas and rhododendrons, and also noted how a thicket might be planted in a spiral or [[labyrinth]] formation with [[walk]]s between rows of plants. Such forms and materials were quite close to those formed in [[wilderness]] [[hedge]]s or graduated [[shrubberies]]. | |

| − | + | The plants used to compose thickets varied widely. [[Eliza Lucas Pinckney|Pinckney]], for example, described a thicket of young oaks at William Middleton’s [[plantation]], Crowfield, near Charleston. [[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson]], in addition to suggesting a variety of flowering shrubs, envisioned thickets made entirely of evergreens and other nonflowering plants in his 1806 letter to [[William Hamilton]]. The array of plants recommended by Jefferson was consistent with the advice given by contemporary treatise authors, such as [[Bernard M’Mahon|M’Mahon]], who promoted combinations of hardy deciduous or evergreen trees and shrubs. | |

| − | + | As design elements, thickets were used in many ways. They marked boundaries, directed one’s gaze toward preferred [[view]]s, and screened out undesirable views. Such functions depended upon the density of thicket plantings, and garden literature suggests that thickets were considered akin to impenetrable [[hedge]]s or dense [[shrubberies]] and other boundary markers. For example, c. 1800 the designer of the Elias Hasket Derby House in Salem, Massachusetts, noted that a thicket could be replaced by a [[ha-ha]] or sunk fence to mark the perimeter of the garden. [[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson]], in 1806, described how at Monticello thickets could be used to circumscribe views. By 1850, [[Andrew Jackson Downing|A. J. Downing]], in his article “How to Arrange Country Places,” stated that thickets should be planted to keep out “unbidden guests.” Downing also recommended the use of tall, dense thickets to screen the sides of [[walk]]s in order to re-create the romantic experience of walking undisturbed in an uncultivated wood. | |

| − | + | Thickets, as [[Bernard M’Mahon|M’Mahon]] noted, were also placed along the outer edges of [[lawn]]s in order to break up the formality of a smooth lawn and to create a setting consistent with the [[Natural_style|natural]] or [[picturesque]] style. Not only was this strategy in accord with the theories of landscape gardening, it also suited the American gardener’s challenge to carve out a garden from what was often heavily wooded land. [[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson]], for example, described cutting away existing vegetation at Monticello to create a series of ordered [[wood]]s, [[clump]]s, and hemispherical thickets. Ironically, less than fifty years later, George Jaques (1851) suggested the reverse of this process, recommending that thickets be planted in the midst of [[common]]s in order to recall the primeval forests that once covered North America. | |

| − | + | —''Anne L. Helmreich'' | |

| − | + | <hr> | |

==Texts== | ==Texts== | ||

| − | |||

===Usage=== | ===Usage=== | ||

| + | *[[Eliza Lucas Pinckney|Pinckney, Eliza Lucas]], May 1743, describing Crowfield, plantation of William Middleton, vicinity of Charleston, SC (1972: 61)<ref>Eliza Lucas Pinckney, ''The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 1739–1762'', ed. Elise Pinckney (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/EBQQ2RAU view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“Next to that on the right hand is what imediately struck my rural taste, a '''thicket''' of young tall live oaks where a variety of Airry Chorristers pour forth their melody.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Kalm, Pehr, September 21, 1748, describing the vicinity of Philadelphia, PA (1937: 1:47)<ref>Pehr Kalm, ''The America of 1750: Peter Kalm’s Travels in North America. The English Version of 1770'', 2 vols. (New York: Wilson-Erickson, 1937), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/94EZM2V4 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“The common privet, or ''Ligustrum vulgare'' L., grows among the bushes in '''thickets''' and [[wood]]s.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Manasseh Cutler|Cutler, Manasseh]], July 14, 1787, describing Gray’s Tavern, Philadelphia, PA (1987: 1:276)<ref name="Cutler">William Parker Cutler, ''Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D.'' (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1987), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3PBNT7H9 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“At this [[hermitage]] we came into a spacious graveled [[walk]], which directed its course further along the [[grove]], which was tall wood interspersed with close '''thickets''' of different growth. As we advanced, we found our gravel walk dividing itself into numerous branches, leading into different parts of the [[grove]].” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

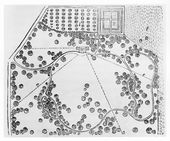

| − | + | [[File:2250_detail1.jpg|thumb|Fig. 2, Unknown, Kitchen Garden [detail], Elias Hasket Derby House, c. 1795-99.]] | |

| − | + | *Anonymous, c. 1800, describing Elias Hasket Derby Farm, Peabody, MA (Peabody Essex Institute, Phillips Library, Derby Papers) | |

| − | + | :“If there is any [[Prospect]] that is agreeable can be seen from the House make a [[Ha-Ha]] instead of a '''Thicket'''.” [Fig. 2] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Manasseh Cutler|Cutler, Manasseh]], January 2, 1802, describing [[Mount Vernon]], plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1987: 2:57)<ref name="Cutler"></ref> | |

| − | + | :“The side of the steep bank to the river is covered with a '''thicket''' of forest trees in its whole extent within [[view]] of the house.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

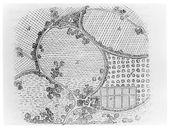

| − | describing | + | [[File:0090.jpg|thumb|Fig. 3, [[Thomas Jefferson]], Letter describing plans for a “Garden Olitory,” c. 1804. The spiral diagram indicates a thicket.]] |

| − | + | *[[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson, Thomas]], c. 1804, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (quoted in Nichols and Griswold 1978: 111–12)<ref>Frederick Doveton Nichols and Ralph E. Griswold, ''Thomas Jefferson, Landscape Architect'' (Charlottesville, Va.: University Press of Virginia, 1978), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/RUZC4Q3D view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| + | :“The canvas at large must be [[Grove]], of the largest trees, (poplar, oak, elm, maple, ash, hickory, chestnut, Linden, Weymouth pine, sycamore) trimmed very high, so as to give it the appearance of open ground, yet not so far apart but that they may cover the ground with close shade. | ||

| + | :“This must be broken by [[clump]]s of '''thicket''', as the open grounds of the English are broken by [[clump]]s of trees. plants for '''thickets''' are broom, calycanthus, altheas, gelder rose, magnolia glauca, azalea, fringe tree, dogwood, red bud, wild crab, kalmia, mezereon, euonymous, halesia, quamoclid, rhododendron, oleander, service tree, lilac, honeysuckle, brambles. [Fig. 3] | ||

| + | :“Vistas to very interesting objects may be permitted, but in general it is better so to arange the '''thickets''' as that they may have the effect of [[vista]] in various directions. . . | ||

| + | :“a '''thicket''' may be of Cedar, topped into a bush, for the center, surrounded by Kalmia. or it may be of Scotch broom alone.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Jefferson, Thomas, | + | *[[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson, Thomas]], July 1806, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1944: 323–24)<ref>Thomas Jefferson, ''The Garden Book'', ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/8ZA5VRP5 view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, | + | :“The grounds which I destine to improve in the style of the English gardens are in a form very difficult to be managed. . . They are chiefly still in their native [[wood]]s. which are majestic, and very generally a close undergrowth, which I have not suffered to be touched, knowing how much easier it is to cut away than to fill up. The upper third is chiefly open, but to the South is covered with a dense '''thicket''' of Scotch broom (Spartium scoparium Lin.) which being favorably spread before the sun will admit of advantageous arrangement for winter enjoyment. . . |

| − | + | :“Let your ground be covered with trees of the loftiest stature. Trim up their bodies as high as the constitution & form of the tree will bear, but so as that their tops shall still unite & yield dense shade. A [[wood]], so open below, will have nearly the appearance of open grounds. Then, when in the open ground you would plant a [[clump]] of trees, place a '''thicket''' of shrubs presenting a hemisphere the crown of which shall distinctly show itself under the branches of the trees. This may be effected by a due selection & arrangement of the shrubs, & will I think offer a group not much inferior to that of trees. The '''thickets''' may be varied too by making some of them of evergreens altogether, our red cedar made to grow in a bush, evergreen privet, pyrocanthus, Kalmia, Scotch broom. Holly would be elegant but it does not grow in my part of the country. | |

| − | + | :“Of [[prospect]] I have a rich profusion and offering itself at every point of the compass. Mountains distant & near, smooth & shaggy, single & in ridges, a little river hiding itself among the hills so as to shew in lagoons only, cultivated grounds under the eye and two small villages. To present a satiety of this is the principal difficulty. It may be successively offered, & in different portions through [[vista]]s, or which will be better, between '''thickets''' so disposed as to serve as [[vista]]s, with the advantage of shifting the scenes as you advance your way.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Waln, Robert, Jr., 1825, describing the Friends Asylum for the Insane, near Frankford, PA (1825: 233)<ref>Robert Waln Jr., “An Account of the Asylum for the Insane, Established by the Society of Friends, near Frankford, in the Vicinity of Philadelphia,” ''Philadelphia Journal of the Medical and Physical Sciences'' 1 (new series, 1825), 225–51, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/D39BHTPH view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“[At the [[Temple]] of Solitude in the woodland]. . . on the right appears a dark and almost impenetrable '''thicket''', skirting and overshadowing the rivulet.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Kemble, Fanny, January 1839, describing her husband’s [[plantation|plantations]] on Butler Island, GA (1984: 56)<ref>Frances Anne Kemble, ''Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838–1839'', ed. John A. Scott (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1984), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/UWZQAT2D view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“My [[walk]]s are rather circumscribed, inasmuch as the dikes are the only [[promenade]]s. On all sides of these lie either the marshy rice fields, the brimming river, or the swampy patches of yet unreclaimed forest, where the huge cypress trees and exquisite evergreen undergrowth spring up from a stagnant sweltering pool, that effectually forbids the foot of the explorer. | |

| − | + | :“As I skirted one of these '''thickets''' today, I stood still to admire the beauty of the [[shrubbery]].” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], October 1847, describing [[Montgomery Place]], country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (quoted in Haley 1988: 45)<ref>Jacquetta M. Haley, ed., ''Pleasure Grounds: Andrew Jackson Downing and Montgomery Place'' (Tarrytown, NY: Sleepy Hollow Press, 1988), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/SSZXJFSC view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“Its richness of foliage, both in natural wood and planted trees, is one of its marked features. Indeed, so great is the variety and intricacy of scenery, caused by the leafy woods, '''thickets''' and bosquets, that one may pass days and even weeks here, and not thoroughly explore all its fine points.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Jaques, George, February 1851, “Trees in Cities,” describing Worcester, MA (''Magazine of Horticulture'' 17: 52)<ref>George Jaques, “Trees in Cities,” ''Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs'' 17, no. 2 (February 1851): 50−52, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/87A6ZJSH/q/trees%20in%20cities view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“Suppose the trees upon the [[Common]] were gathered together in groups,—here a '''thicket''', there a wide space of open [[lawn]]; or suppose the primitive forest,—such as perhaps once grew there,—had remained, and clearings been made with a bold hand to let in the sunshine, would you not prefer either of these conditions to the present one, beautiful as it may be?” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ( | + | ===Citations=== |

| − | + | *Langley, Batty, 1728, ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728; repr., 1982: XIV)<ref>Batty Langley, ''New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c.'' (1728; repr. New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1982), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/MRDTAEKC view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :We having thus paffed through all the most pleafant Parts of a ''delightful rural Garden'', we muft now fuppofe, that we are entering from X Y, of Plate III, at Z of Plate XIII, where we furprizingly behold a ''pleasant semi-circular Lawn'', from which the ''grand Avenu''e V, V, of Plate III. is continued to H, ''&c''. throughout the whole Eftate. And we are here again in every of its Parts entertain'd with ''different [[View]]s, open Plains, [[Grove]]s, '''Thickets''', open and private Fish [[Pond]]s'', and ''in brief every Thing that's pleasant.'' | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Whately, Thomas, 1770, ''Observations on Modern Gardening'' (1770; repr., 1982: 34, 36)<ref>Thomas Whately, ''Observations on Modern Gardening'', 3rd ed. (1770; repr., London: Garland, 1982), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/QKRK8DCD view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“A small '''thicket''' is generally most agreeable, when it is one fine mass of well-mixed greens: that mass gives to the whole a ''unity'', which can by no other means be so perfectly expressed. When more than one is necessary for the extent of the [[plantation]], still if they are not too much contrasted, if the gradations from one to another are easy, the unity is not broken by the variety. . . | |

| − | of | + | :“A [[wood]] is composed both of trees and underwood, covering a considerable space. A [[grove]] consists of trees without underwood; a [[clump]] differs from either only in extent; it may be either close or open; when close, it is sometimes called a '''''thicket'''''; when open, a groupe of trees; but both are equally [[clump]]s, whatever be the shape or situation.” |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Marshall, Charles, 1799, ''An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening'' (1799: 1:119)<ref>Charles Marshall, ''An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening'', 1st American ed., 2 vols. (Boston: Samuel Etheridge, 1799), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/DVB7T4I2 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“As to small [[plantation|plantations]], of '''''thickets''''', ''[[coppices]]'', ''[[clump]]s'', and ''rows'' of trees, they are to be set close according to their ''nature'', and the particular [[view]] the planter has, who will take care to consider the usual size they attain, and their ''mode'' of growth. An advantage at home for shade or shelter, and a more distant object of sight, will make a difference: for some immediate advantage, ''very'' close planting may take place, but good trees cannot be thus expected; yet if thinned ''in time'', a strait tall stem is often thus procured, which afterwards is of great advantage.” | |

| − | ( | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Bernard M’Mahon|M’Mahon, Bernard]], 1806, ''The American Gardener’s Calendar'' (1806: 57, 63–64)<ref>Bernard M’Mahon, ''The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done. . . for Every Month of the Year. . .'' (Philadelphia: printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/HU4JIS9C view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“First an open [[lawn]] of grass-ground is extended on one of the principal fronts of the mansion or main house, widening gradually from the house outward, having each side bounded by various [[plantation|plantations]] of trees, shrubs, and flowers, in [[clump]]s, '''thickets''', &c. exhibited in a variety of rural forms, in moderate concave and convex curves, and projections, to prevent all appearance of a stiff uniformity. . . | |

| − | + | :“'''Thickets''' may be composed of all sorts of hardy deciduous trees planted close and promiscuously, and with various common shrubs interspersed between them, as underwood, to make them more or less close in different parts, as the designer may think proper. They may also be of ever-green trees, particularly of the pine and fir kinds, interspersed with various low-growing ever-green shrubs.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Abercrombie, John, with James Mean, 1817, ''Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener'' (1817: 479)<ref>John Abercrombie, ''Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener Or, Improved System of Modern Horticulture'' (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1817), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TH54TADZ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| + | :“A '''''thicket''''' differs from a [[clump]], in comprising thorns and underwood as well as trees, while it is too small to be called a [[wood]]. It admits more variety and wildness than the clump; but should be farther removed from the polished lawn.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

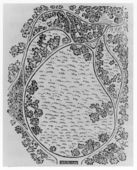

| − | + | [[File:1181.jpg|thumb|Fig. 4, [[J. C. Loudon]], Thicket [detail], in ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (1826), 942, figs. 628b and c.]] | |

| − | + | *[[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius)]], 1826, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (1826: 942, 954)<ref>J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening'', 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KNKTCA4W view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“6811. In regard to extent, the least is a group. . . which must consist at least of two plants; larger, it is called a '''thicket''' (''b c''); round and compact, it is called a [[clump]] (''a''); still larger, a mass; and all above a mass is denominated a ''[[wood]]'' or ''forest'', and characterised by comparative degrees of largeness. The term [[wood]] may be applied to a large assemblage of trees, either natural or artificial; forest, exclusively to the most extensive or natural assemblages. . . [Fig. 4] | |

| − | + | [[File:1361.jpg|thumb|Fig. 5, [[J. C. Loudon]], The placement of groups and thickets in plantations, in ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (1826), p. 954, fig. 649. ]] | |

| − | + | :“6861. ''Placing the groups''. Another practice in the employment of groups, almost equally reprehensible with that of indiscriminate distribution, is that of placing the groups and '''thickets''' in the recesses, instead of chiefly employing them opposite the salient points. The effect of this mode is the very reverse of what is intended; for, instead of varying the outline, it tends to render it more uniform by diminishing the depth of recesses, and approximating the whole more nearly to an even line. The way to vary an even or straight line or lines, is here and there to place constellations of groups against it. . . and a line already varied is to be rendered more so, by placing large groups against the prominences (a) to render them more prominent; and small groups (b), here and there in the recesses, to vary their forms and conceal their real depths.” [Fig. 5] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Buist, Robert, 1841, ''The American Flower Garden Directory'' (1841: 20)<ref>Robert Buist, ''The American Flower Garden Directory,'' 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1841), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TI7IE55B view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“Thick masses of [[shrubbery]], called '''thickets''', are sometimes wanted. In these there should be plenty of evergreens. A mass of deciduous shrubs has no imposing effect during winter.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], 1844, Excerpt from ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America; . . . '' (1844: 102)<ref>A. J. Downing, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America; with a View to the Improvement of Country Residences. . . with Remarks on Rural Architecture'', 2nd ed. (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1844), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IGJXRU9V view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :"In fig. 25, is shown a small piece of ground, on one side of a cottage, in which a [[picturesque]] character is attempted to be maintained. The [[plantation]]s here, are made mostly with shrubs instead of trees, the latter being only sparingly introduced, for the want of room. In the disposition of these shrubs, however, the same attention to [[picturesque]] effect is paid as we have already pointed out in our remarks on grouping ; and by connecting the '''thickets''' and groups here and there, so as to conceal one [[walk]] from the other, a surprising variety and effect will frequently be produced, in an exceedingly limited spot." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], 1849, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849: 93, 95, 104–5, 112–13, 119–20, 250)<ref>A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America'', 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/K7BRCDC5 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“were a person to desire a residence newly laid out and planted, in a district where all around is in a high state of polished cultivation, as in the suburbs of a city, a species of pleasure would result from the imitation of scenery of a more spirited, natural character, as the [[picturesque]], in his grounds. His [the homeowner] [[plantation]]s are made in irregular groups, composed chiefly of [[picturesque]] trees, as the larch, &c.—his [[walk]]s would lead through varied scenes. . . sometimes with '''thickets''' or little [[copse]]s of shrubs and flowering plants. . . | |

| − | and with | + | [[File:0376.jpg|thumb|Fig. 6, Anonymous, “Plan of the foregoing grounds as a Country Seat, after ten years' improvement,” in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849), p. 114, fig. 24. At ''b'' this plan depicts “varied [[walk]]s concealed from each other by the intervening masses of thicket.”]] |

| − | + | :“And as the [[Avenue]], or the straight line, is the leading form in the geometric arrangement of [[plantation]]s, so let us enforce it upon our readers, the GROUP is equally the key-note of the [[Modern style]]. The smallest place, having only three trees, may have these pleasingly connected in a group; and the largest and finest park—the Blenheim or Chatsworth, of seven miles square, is only composed of a succession of groups, becoming masses, '''thickets''', [[wood]]s. . . | |

| − | + | :“In order to know how a [[plantation]] in the [[Picturesque]] mode should be treated, after it is established, we should reflect a moment on what constitutes picturesqueness in any tree. . . He [the cultivator of trees] desires to encourage a certain wildness of growth, and allows his trees to spring up occasionally in '''thickets''' to assist this effect. . . | |

| − | + | :“GROUND PLANS OF ORNAMENTAL [[Plantation|PLANTATIONS]]. . . | |

| − | + | [[File:0379.jpg|thumb|Fig. 7, Anonymous, “View of a Picturesque farm (ferme ornée),” in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849), p. 120, fig. 27. In describing this plan, Downing refers to “a low dell, or rocky thicket” that is situated at “i” in the densley planted area in the triangle at top. ]] | |

| − | + | :“In the next figure. . . a ground plan of the place is given, as it would appear after having been judiciously laid out and planted, with several years’ growth. At ''a'', the approach road leaves the public highway and leads to the house at ''c'': from whence paths of smaller size, ''b'', make the circuit of the ornamental portion of the residence, taking advantage of the wooded dells, ''d'', originally existing, which offer some scope for varied [[walk]]s concealed from each other by the intervening masses of '''thicket'''. . . [Fig. 6] | |

| − | + | :“The embellished farm (''ferme ornée'') is a pretty mode of combining something of the beauty of the landscape garden with the utility of the farm, and we hope to see small country [[seat]]s of this kind become more general. . . A low dell, or rocky '''thicket''', is situated at i. . . [Fig. 7] | |

| + | :“The Hawthorn is most agreeable to the eye in composition when it forms the undergrowth or '''thicket''', peeping out in all its green freshness, gay blossoms, or bright fruit, from beneath and between the groups and masses of trees; where, mingled with the hazel, etc., it gives a pleasing intricacy to the whole mass of foliage. But the different species display themselves to most advantage, and grow also to a finer size, when planted singly, or two or three together, along the [[walk]]s leading through the different parts of the [[pleasure-ground]] or [[shrubbery]].” | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], March 1850, “How to Arrange Country Places” (''Horticulturist'' 4: 396)<ref>A. J. Downing, “How to Arrange Country Places,” ''Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste'' 4, no. 9 (March 1850): 393–96, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/7HNUGQK2/q/how%20to%20arrange%20country%20places view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| + | :“In residences where there is little or no distant [[view]], the contrary plan must be pursued. Intricacy and variety must be created by planting. [[Walk]]s must be led in various directions, and concealed from each other by '''thickets''', and masses of shrubs and trees, and occasionally rich masses of foliage; not forgetting to heighten all, however, by an occasional contrast of broad, unbroken surface of [[lawn]]. | ||

| + | :“In all country places, and especially in small ones, a great object to be kept in view in planting, is to produce as perfect seclusion and privacy within the grounds as possible. We do not entirely feel that to be our own, which is indiscriminately enjoyed by each passer by, and every man’s individuality and home-feeling is invaded by the presence of unbidden guests. Therefore, while you preserve the beauty of the [[view]], shut out, by boundary belts and '''thickets''', all eyes but those that are fairly within your own grounds. This will enable you to feel at home all over your place.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], September 1851, “Study of Park Trees” (''Horticulturist'' 6: 427)<ref>A. J. Downing, “Study of Park Trees,” ''Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste'' 6, no. 9 (September 1851): 427, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/NIE2MS4I/q/study%20of%20park%20trees view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | ( | + | :“Even in our ornamental grounds, it is too much the custom to plant trees in masses, belts, and '''thickets'''—by which the same effects are produced as we constantly see in ordinary [[wood]]s— that is, there is [[picturesque]] intricacy, depth of shadow, and seclusion, growing out of masses of verdure—but no beauty of development in each individual tree—and none of that fine perfection of character which is seen when a noble forest tree stands alone in soil well suited to it, and has ‘nothing else to do but grow’ into the finest possible shape that nature meant it to take.” |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <hr> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Images== | |

| − | + | ===Inscribed=== | |

| + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| − | + | File:0002.jpg|Anonymous, Surveyor’s [[Plot/Plat|plat]] of the courthouse and adjacent land Charles County, MD, 1697. The trees in the lower part of the image are labeled “'''Thickett'''” on the right edge. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:2249.jpg|Unknown, Derby Garden, [circa 1795–1799], Samuel McIntire Papers, MSS 264, flat file, plan 107. Courtesy of Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Rowley, MA. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:0090.jpg|[[Thomas Jefferson]], Letter describing plans for a “Garden Olitory,” c. 1804. The spiral diagram indicates a '''thicket'''. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:1196.jpg|Humphry Repton, Sketch of Planting [[Clump]]s, in ''Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1805), 50. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:0968.jpg|[[Thomas Jefferson]], Plan of [[Monticello]] with oval and round flower [[bed]]s [detail], 1807. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:1181.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], '''Thicket''' [detail], in ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'', 4th ed. (1826), 942, figs. 628b and c. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | File:1361.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], The placement of groups and '''thickets''' in [[plantation]]s, in ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'', 4th ed. (1826), 954, fig. 649. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | File:0376.jpg|Anonymous, “Plan of the foregoing grounds as a Country Seat, after ten years' improvement,” in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'', 4th ed. (1849), 114, fig. 24. At ''b'' this plan depicts “varied [[walk]]s concealed from each other by the intervening masses of '''thicket'''.” | ||

| − | + | File:0379.jpg|Anonymous, “[[View]] of a [[Picturesque]] farm ([[Ferme_ornée/Ornamental_farm|ferme ornée]]),” in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'', 4th ed. (1849), 120, fig. 27. In describing this plan, Downing refers to “a low dell, or rocky '''thicket'''” that is situated at “i” in the densely planted area in the triangle at top. | |

| − | of | + | </gallery> |

| − | + | ===Associated=== | |

| − | + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:2250_detail1.jpg|Unknown, [[Kitchen_garden|Kitchen Garden]] [detail], Elias Hasket Derby House, c. 1795-99. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:0092.jpg|[[Thomas Jefferson]], “Plan of Spring Roundabout at [[Monticello]],” c. 1804. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | File:1861.jpg|Anonymous, ''Grounds of a cottage orneé'', in A. J. Downing, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening,'' (1844): 102, fig. 25. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | </gallery> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Attributed=== | |

| − | + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | |

| − | + | File:1389.jpg|Batty Langley, “Variety of ''[[Lawn]]s'', or ''Openings'', before a ''grand Front of a Building'', into a ''[[Park]], Forest, [[Common]]'', &c.” in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728), pl. XVI. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:0021.jpg|Cornelius Tiebout, ''A [[View]] of the present [[Seat]] of his Excel. the Vice President of the United States'', 1790. | |

| + | </gallery> | ||

| − | < | + | <hr> |

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 428: | Line 182: | ||

[[Category: Keywords]] | [[Category: Keywords]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Planting Arrangements]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:44, February 3, 2021

See also: Clump, Copse, Grove, Labyrinth, Plantation, Shrubbery, Wilderness, Wood

History

Although thicket is not mentioned as frequently as other planting terms in 18th- and 19th-century garden literature, it is nonetheless significant as a description for naturally occurring and designed features [Fig. 1]. According to Thomas Whately, whose 1770 definition was quoted or paraphrased by garden writers for the next century, a thicket was a dense planting of woods underplanted with shrubs, akin to a closed clump or copse. British treatise author Charles Marshall (1799) used “coppice” synonymously with “thicket.” American writers such as Bernard M’Mahon (1806) offered similar definitions, describing a thicket as closely planted trees with shrubs. It was distinguished from a clump, copse, or wood by its compactness and smaller scale.

This connotation was found in American accounts written by Eliza Lucas Pinckney (1743), Manasseh Cutler (1787 and 1802), and Thomas Jefferson (1806). A more detailed portrayal of thicket was provided by Jefferson in a letter of 1804. In this document, he indicated which plants to include in the thicket, such as azaleas and rhododendrons, and also noted how a thicket might be planted in a spiral or labyrinth formation with walks between rows of plants. Such forms and materials were quite close to those formed in wilderness hedges or graduated shrubberies.

The plants used to compose thickets varied widely. Pinckney, for example, described a thicket of young oaks at William Middleton’s plantation, Crowfield, near Charleston. Jefferson, in addition to suggesting a variety of flowering shrubs, envisioned thickets made entirely of evergreens and other nonflowering plants in his 1806 letter to William Hamilton. The array of plants recommended by Jefferson was consistent with the advice given by contemporary treatise authors, such as M’Mahon, who promoted combinations of hardy deciduous or evergreen trees and shrubs.

As design elements, thickets were used in many ways. They marked boundaries, directed one’s gaze toward preferred views, and screened out undesirable views. Such functions depended upon the density of thicket plantings, and garden literature suggests that thickets were considered akin to impenetrable hedges or dense shrubberies and other boundary markers. For example, c. 1800 the designer of the Elias Hasket Derby House in Salem, Massachusetts, noted that a thicket could be replaced by a ha-ha or sunk fence to mark the perimeter of the garden. Jefferson, in 1806, described how at Monticello thickets could be used to circumscribe views. By 1850, A. J. Downing, in his article “How to Arrange Country Places,” stated that thickets should be planted to keep out “unbidden guests.” Downing also recommended the use of tall, dense thickets to screen the sides of walks in order to re-create the romantic experience of walking undisturbed in an uncultivated wood.

Thickets, as M’Mahon noted, were also placed along the outer edges of lawns in order to break up the formality of a smooth lawn and to create a setting consistent with the natural or picturesque style. Not only was this strategy in accord with the theories of landscape gardening, it also suited the American gardener’s challenge to carve out a garden from what was often heavily wooded land. Jefferson, for example, described cutting away existing vegetation at Monticello to create a series of ordered woods, clumps, and hemispherical thickets. Ironically, less than fifty years later, George Jaques (1851) suggested the reverse of this process, recommending that thickets be planted in the midst of commons in order to recall the primeval forests that once covered North America.

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Pinckney, Eliza Lucas, May 1743, describing Crowfield, plantation of William Middleton, vicinity of Charleston, SC (1972: 61)[1]

- “Next to that on the right hand is what imediately struck my rural taste, a thicket of young tall live oaks where a variety of Airry Chorristers pour forth their melody.”

- Kalm, Pehr, September 21, 1748, describing the vicinity of Philadelphia, PA (1937: 1:47)[2]

- “The common privet, or Ligustrum vulgare L., grows among the bushes in thickets and woods.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 14, 1787, describing Gray’s Tavern, Philadelphia, PA (1987: 1:276)[3]

- “At this hermitage we came into a spacious graveled walk, which directed its course further along the grove, which was tall wood interspersed with close thickets of different growth. As we advanced, we found our gravel walk dividing itself into numerous branches, leading into different parts of the grove.”

- Anonymous, c. 1800, describing Elias Hasket Derby Farm, Peabody, MA (Peabody Essex Institute, Phillips Library, Derby Papers)

- “If there is any Prospect that is agreeable can be seen from the House make a Ha-Ha instead of a Thicket.” [Fig. 2]

- Cutler, Manasseh, January 2, 1802, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1987: 2:57)[3]

- “The side of the steep bank to the river is covered with a thicket of forest trees in its whole extent within view of the house.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, c. 1804, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (quoted in Nichols and Griswold 1978: 111–12)[4]

- “The canvas at large must be Grove, of the largest trees, (poplar, oak, elm, maple, ash, hickory, chestnut, Linden, Weymouth pine, sycamore) trimmed very high, so as to give it the appearance of open ground, yet not so far apart but that they may cover the ground with close shade.

- “This must be broken by clumps of thicket, as the open grounds of the English are broken by clumps of trees. plants for thickets are broom, calycanthus, altheas, gelder rose, magnolia glauca, azalea, fringe tree, dogwood, red bud, wild crab, kalmia, mezereon, euonymous, halesia, quamoclid, rhododendron, oleander, service tree, lilac, honeysuckle, brambles. [Fig. 3]

- “Vistas to very interesting objects may be permitted, but in general it is better so to arange the thickets as that they may have the effect of vista in various directions. . .

- “a thicket may be of Cedar, topped into a bush, for the center, surrounded by Kalmia. or it may be of Scotch broom alone.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, July 1806, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1944: 323–24)[5]

- “The grounds which I destine to improve in the style of the English gardens are in a form very difficult to be managed. . . They are chiefly still in their native woods. which are majestic, and very generally a close undergrowth, which I have not suffered to be touched, knowing how much easier it is to cut away than to fill up. The upper third is chiefly open, but to the South is covered with a dense thicket of Scotch broom (Spartium scoparium Lin.) which being favorably spread before the sun will admit of advantageous arrangement for winter enjoyment. . .

- “Let your ground be covered with trees of the loftiest stature. Trim up their bodies as high as the constitution & form of the tree will bear, but so as that their tops shall still unite & yield dense shade. A wood, so open below, will have nearly the appearance of open grounds. Then, when in the open ground you would plant a clump of trees, place a thicket of shrubs presenting a hemisphere the crown of which shall distinctly show itself under the branches of the trees. This may be effected by a due selection & arrangement of the shrubs, & will I think offer a group not much inferior to that of trees. The thickets may be varied too by making some of them of evergreens altogether, our red cedar made to grow in a bush, evergreen privet, pyrocanthus, Kalmia, Scotch broom. Holly would be elegant but it does not grow in my part of the country.

- “Of prospect I have a rich profusion and offering itself at every point of the compass. Mountains distant & near, smooth & shaggy, single & in ridges, a little river hiding itself among the hills so as to shew in lagoons only, cultivated grounds under the eye and two small villages. To present a satiety of this is the principal difficulty. It may be successively offered, & in different portions through vistas, or which will be better, between thickets so disposed as to serve as vistas, with the advantage of shifting the scenes as you advance your way.”

- Waln, Robert, Jr., 1825, describing the Friends Asylum for the Insane, near Frankford, PA (1825: 233)[6]

- “[At the Temple of Solitude in the woodland]. . . on the right appears a dark and almost impenetrable thicket, skirting and overshadowing the rivulet.”

- Kemble, Fanny, January 1839, describing her husband’s plantations on Butler Island, GA (1984: 56)[7]

- “My walks are rather circumscribed, inasmuch as the dikes are the only promenades. On all sides of these lie either the marshy rice fields, the brimming river, or the swampy patches of yet unreclaimed forest, where the huge cypress trees and exquisite evergreen undergrowth spring up from a stagnant sweltering pool, that effectually forbids the foot of the explorer.

- “As I skirted one of these thickets today, I stood still to admire the beauty of the shrubbery.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, October 1847, describing Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (quoted in Haley 1988: 45)[8]

- “Its richness of foliage, both in natural wood and planted trees, is one of its marked features. Indeed, so great is the variety and intricacy of scenery, caused by the leafy woods, thickets and bosquets, that one may pass days and even weeks here, and not thoroughly explore all its fine points.”

- Jaques, George, February 1851, “Trees in Cities,” describing Worcester, MA (Magazine of Horticulture 17: 52)[9]

- “Suppose the trees upon the Common were gathered together in groups,—here a thicket, there a wide space of open lawn; or suppose the primitive forest,—such as perhaps once grew there,—had remained, and clearings been made with a bold hand to let in the sunshine, would you not prefer either of these conditions to the present one, beautiful as it may be?”

Citations

- Langley, Batty, 1728, New Principles of Gardening (1728; repr., 1982: XIV)[10]

- We having thus paffed through all the most pleafant Parts of a delightful rural Garden, we muft now fuppofe, that we are entering from X Y, of Plate III, at Z of Plate XIII, where we furprizingly behold a pleasant semi-circular Lawn, from which the grand Avenue V, V, of Plate III. is continued to H, &c. throughout the whole Eftate. And we are here again in every of its Parts entertain'd with different Views, open Plains, Groves, Thickets, open and private Fish Ponds, and in brief every Thing that's pleasant.

- Whately, Thomas, 1770, Observations on Modern Gardening (1770; repr., 1982: 34, 36)[11]

- “A small thicket is generally most agreeable, when it is one fine mass of well-mixed greens: that mass gives to the whole a unity, which can by no other means be so perfectly expressed. When more than one is necessary for the extent of the plantation, still if they are not too much contrasted, if the gradations from one to another are easy, the unity is not broken by the variety. . .

- “A wood is composed both of trees and underwood, covering a considerable space. A grove consists of trees without underwood; a clump differs from either only in extent; it may be either close or open; when close, it is sometimes called a thicket; when open, a groupe of trees; but both are equally clumps, whatever be the shape or situation.”

- Marshall, Charles, 1799, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening (1799: 1:119)[12]

- “As to small plantations, of thickets, coppices, clumps, and rows of trees, they are to be set close according to their nature, and the particular view the planter has, who will take care to consider the usual size they attain, and their mode of growth. An advantage at home for shade or shelter, and a more distant object of sight, will make a difference: for some immediate advantage, very close planting may take place, but good trees cannot be thus expected; yet if thinned in time, a strait tall stem is often thus procured, which afterwards is of great advantage.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (1806: 57, 63–64)[13]

- “First an open lawn of grass-ground is extended on one of the principal fronts of the mansion or main house, widening gradually from the house outward, having each side bounded by various plantations of trees, shrubs, and flowers, in clumps, thickets, &c. exhibited in a variety of rural forms, in moderate concave and convex curves, and projections, to prevent all appearance of a stiff uniformity. . .

- “Thickets may be composed of all sorts of hardy deciduous trees planted close and promiscuously, and with various common shrubs interspersed between them, as underwood, to make them more or less close in different parts, as the designer may think proper. They may also be of ever-green trees, particularly of the pine and fir kinds, interspersed with various low-growing ever-green shrubs.”

- Abercrombie, John, with James Mean, 1817, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener (1817: 479)[14]

- “A thicket differs from a clump, in comprising thorns and underwood as well as trees, while it is too small to be called a wood. It admits more variety and wildness than the clump; but should be farther removed from the polished lawn.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 942, 954)[15]

- “6811. In regard to extent, the least is a group. . . which must consist at least of two plants; larger, it is called a thicket (b c); round and compact, it is called a clump (a); still larger, a mass; and all above a mass is denominated a wood or forest, and characterised by comparative degrees of largeness. The term wood may be applied to a large assemblage of trees, either natural or artificial; forest, exclusively to the most extensive or natural assemblages. . . [Fig. 4]

- “6861. Placing the groups. Another practice in the employment of groups, almost equally reprehensible with that of indiscriminate distribution, is that of placing the groups and thickets in the recesses, instead of chiefly employing them opposite the salient points. The effect of this mode is the very reverse of what is intended; for, instead of varying the outline, it tends to render it more uniform by diminishing the depth of recesses, and approximating the whole more nearly to an even line. The way to vary an even or straight line or lines, is here and there to place constellations of groups against it. . . and a line already varied is to be rendered more so, by placing large groups against the prominences (a) to render them more prominent; and small groups (b), here and there in the recesses, to vary their forms and conceal their real depths.” [Fig. 5]

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory (1841: 20)[16]

- “Thick masses of shrubbery, called thickets, are sometimes wanted. In these there should be plenty of evergreens. A mass of deciduous shrubs has no imposing effect during winter.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1844, Excerpt from A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America; . . . (1844: 102)[17]

- "In fig. 25, is shown a small piece of ground, on one side of a cottage, in which a picturesque character is attempted to be maintained. The plantations here, are made mostly with shrubs instead of trees, the latter being only sparingly introduced, for the want of room. In the disposition of these shrubs, however, the same attention to picturesque effect is paid as we have already pointed out in our remarks on grouping ; and by connecting the thickets and groups here and there, so as to conceal one walk from the other, a surprising variety and effect will frequently be produced, in an exceedingly limited spot."

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849: 93, 95, 104–5, 112–13, 119–20, 250)[18]

- “were a person to desire a residence newly laid out and planted, in a district where all around is in a high state of polished cultivation, as in the suburbs of a city, a species of pleasure would result from the imitation of scenery of a more spirited, natural character, as the picturesque, in his grounds. His [the homeowner] plantations are made in irregular groups, composed chiefly of picturesque trees, as the larch, &c.—his walks would lead through varied scenes. . . sometimes with thickets or little copses of shrubs and flowering plants. . .

- “And as the Avenue, or the straight line, is the leading form in the geometric arrangement of plantations, so let us enforce it upon our readers, the GROUP is equally the key-note of the Modern style. The smallest place, having only three trees, may have these pleasingly connected in a group; and the largest and finest park—the Blenheim or Chatsworth, of seven miles square, is only composed of a succession of groups, becoming masses, thickets, woods. . .

- “In order to know how a plantation in the Picturesque mode should be treated, after it is established, we should reflect a moment on what constitutes picturesqueness in any tree. . . He [the cultivator of trees] desires to encourage a certain wildness of growth, and allows his trees to spring up occasionally in thickets to assist this effect. . .

- “GROUND PLANS OF ORNAMENTAL PLANTATIONS. . .

- “In the next figure. . . a ground plan of the place is given, as it would appear after having been judiciously laid out and planted, with several years’ growth. At a, the approach road leaves the public highway and leads to the house at c: from whence paths of smaller size, b, make the circuit of the ornamental portion of the residence, taking advantage of the wooded dells, d, originally existing, which offer some scope for varied walks concealed from each other by the intervening masses of thicket. . . [Fig. 6]

- “The embellished farm (ferme ornée) is a pretty mode of combining something of the beauty of the landscape garden with the utility of the farm, and we hope to see small country seats of this kind become more general. . . A low dell, or rocky thicket, is situated at i. . . [Fig. 7]

- “The Hawthorn is most agreeable to the eye in composition when it forms the undergrowth or thicket, peeping out in all its green freshness, gay blossoms, or bright fruit, from beneath and between the groups and masses of trees; where, mingled with the hazel, etc., it gives a pleasing intricacy to the whole mass of foliage. But the different species display themselves to most advantage, and grow also to a finer size, when planted singly, or two or three together, along the walks leading through the different parts of the pleasure-ground or shrubbery.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, March 1850, “How to Arrange Country Places” (Horticulturist 4: 396)[19]

- “In residences where there is little or no distant view, the contrary plan must be pursued. Intricacy and variety must be created by planting. Walks must be led in various directions, and concealed from each other by thickets, and masses of shrubs and trees, and occasionally rich masses of foliage; not forgetting to heighten all, however, by an occasional contrast of broad, unbroken surface of lawn.

- “In all country places, and especially in small ones, a great object to be kept in view in planting, is to produce as perfect seclusion and privacy within the grounds as possible. We do not entirely feel that to be our own, which is indiscriminately enjoyed by each passer by, and every man’s individuality and home-feeling is invaded by the presence of unbidden guests. Therefore, while you preserve the beauty of the view, shut out, by boundary belts and thickets, all eyes but those that are fairly within your own grounds. This will enable you to feel at home all over your place.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, September 1851, “Study of Park Trees” (Horticulturist 6: 427)[20]

- “Even in our ornamental grounds, it is too much the custom to plant trees in masses, belts, and thickets—by which the same effects are produced as we constantly see in ordinary woods— that is, there is picturesque intricacy, depth of shadow, and seclusion, growing out of masses of verdure—but no beauty of development in each individual tree—and none of that fine perfection of character which is seen when a noble forest tree stands alone in soil well suited to it, and has ‘nothing else to do but grow’ into the finest possible shape that nature meant it to take.”

Images

Inscribed

Anonymous, Surveyor’s plat of the courthouse and adjacent land Charles County, MD, 1697. The trees in the lower part of the image are labeled “Thickett” on the right edge.

Thomas Jefferson, Letter describing plans for a “Garden Olitory,” c. 1804. The spiral diagram indicates a thicket.

Humphry Repton, Sketch of Planting Clumps, in Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1805), 50.

Thomas Jefferson, Plan of Monticello with oval and round flower beds [detail], 1807.

J. C. Loudon, Thicket [detail], in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 942, figs. 628b and c.

J. C. Loudon, The placement of groups and thickets in plantations, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 954, fig. 649.

Anonymous, “Plan of the foregoing grounds as a Country Seat, after ten years' improvement,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 114, fig. 24. At b this plan depicts “varied walks concealed from each other by the intervening masses of thicket.”

Anonymous, “View of a Picturesque farm (ferme ornée),” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 120, fig. 27. In describing this plan, Downing refers to “a low dell, or rocky thicket” that is situated at “i” in the densely planted area in the triangle at top.

Associated

Unknown, Kitchen Garden [detail], Elias Hasket Derby House, c. 1795-99.

Thomas Jefferson, “Plan of Spring Roundabout at Monticello,” c. 1804.

Attributed

Notes

- ↑ Eliza Lucas Pinckney, The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 1739–1762, ed. Elise Pinckney (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pehr Kalm, The America of 1750: Peter Kalm’s Travels in North America. The English Version of 1770, 2 vols. (New York: Wilson-Erickson, 1937), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 William Parker Cutler, Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D. (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Doveton Nichols and Ralph E. Griswold, Thomas Jefferson, Landscape Architect (Charlottesville, Va.: University Press of Virginia, 1978), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Waln Jr., “An Account of the Asylum for the Insane, Established by the Society of Friends, near Frankford, in the Vicinity of Philadelphia,” Philadelphia Journal of the Medical and Physical Sciences 1 (new series, 1825), 225–51, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frances Anne Kemble, Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838–1839, ed. John A. Scott (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1984), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jacquetta M. Haley, ed., Pleasure Grounds: Andrew Jackson Downing and Montgomery Place (Tarrytown, NY: Sleepy Hollow Press, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Jaques, “Trees in Cities,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 17, no. 2 (February 1851): 50−52, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Batty Langley, New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c. (1728; repr. New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Whately, Observations on Modern Gardening, 3rd ed. (1770; repr., London: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Marshall, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening, 1st American ed., 2 vols. (Boston: Samuel Etheridge, 1799), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M’Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done. . . for Every Month of the Year. . . (Philadelphia: printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Abercrombie, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener Or, Improved System of Modern Horticulture (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1817), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Buist, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America; with a View to the Improvement of Country Residences. . . with Remarks on Rural Architecture, 2nd ed. (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1844), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “How to Arrange Country Places,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 4, no. 9 (March 1850): 393–96, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “Study of Park Trees,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 6, no. 9 (September 1851): 427, view on Zotero.