Difference between revisions of "Greenhouse"

C-tompkins (talk | contribs) (→Usage) |

C-tompkins (talk | contribs) (→Usage) |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

* [[John Smith|Smith, John]], 1745, describing [[Springettsbury]], near Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Weber 1996: 46–47) <ref>Carmen Weber, "The Greenhouse Effect: Gender-Related Traditions in Eighteenth-Century Gardening," in ''Landscape Archaeology: Reading and Interpreting the American Historical Landscape'', ed. by Rebecca Yamin and Karen Bescherer Metheny (Knoxville: The University of Tennesee Press, 1996), 32–51 [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/92DA3QAZ view on Zotero]</ref> | * [[John Smith|Smith, John]], 1745, describing [[Springettsbury]], near Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Weber 1996: 46–47) <ref>Carmen Weber, "The Greenhouse Effect: Gender-Related Traditions in Eighteenth-Century Gardening," in ''Landscape Archaeology: Reading and Interpreting the American Historical Landscape'', ed. by Rebecca Yamin and Karen Bescherer Metheny (Knoxville: The University of Tennesee Press, 1996), 32–51 [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/92DA3QAZ view on Zotero]</ref> | ||

:“In the afternoon, the weather being so agreeable, John Armitt and I rode to Charles Jenkin’s ferry on Schuykill. We ran and walked a mile or two on the ice. On our way thither we stopped to view the proprietor’s '''green-house''', which at this season is an agreeable sight; the oranges, lemons and citrons were, some green, some ripe, some in blossom.” | :“In the afternoon, the weather being so agreeable, John Armitt and I rode to Charles Jenkin’s ferry on Schuykill. We ran and walked a mile or two on the ice. On our way thither we stopped to view the proprietor’s '''green-house''', which at this season is an agreeable sight; the oranges, lemons and citrons were, some green, some ripe, some in blossom.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | * Anonymous, 1748, describing in the ''South Carolina Gazette'' a property for sale in Charleston, S.C. (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 167) <ref>Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., ''An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994). [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/UK5TCUQQ View on Zotero]</ref> | ||

| + | :“[The dwelling house contains] a large Garden, with two neat '''Green Houses''' for sheltering exotic Fruit-Trees, and Grape-Vines.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | * [[Daniel Fisher|Fisher, Daniel]], 1755, describing the greenhouse in the [[Proprietor’s Garden]], Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Martin 1991: 211) <ref> Peter Martin, ''The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson'' (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1991). [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/6TAHS88N View on Zotero]</ref> | ||

| + | :“What to me surpassed every thing of the kind I had seen in America was a pretty bricked '''Green House''', out of which was disposed very properly in the [[pleasure garden|Pleasure Garden]], a good many Orange, Lemon and Citrous [''sic''] Trees, in great profusion loaded with abundance of Fruit and some of each sort seemingly then ripe.” | ||

Revision as of 15:22, March 4, 2015

(Green house, Green-house)

See also: Conservatory, Hothouse, Nursery, Orangery

History

The term greenhouse designated a plant-keeping house built to protect tender plants from cold weather. Although these structures were most commonly referred to as greenhouses, the terms “conservatory,” “glasshouse,” and “hothouse” were often used synonymously. Attempts were made to distinguish among the terms. According to Bernard M’Mahon (1806), for example, plants were planted in free soil and in “beds and borders” in a conservatory, whereas in a greenhouse, plants were kept in pots or tubs. A. J. Downing later wrote that plants were kept in the greenhouse until they were ready to be displayed in the conservatory. In actual usage, however, the terms were often used interchangeably. “Hothouse” or “stove” was also used to describe that part of the greenhouse with higher temperatures (see also Conservatory, Hothouse, and Orangery).

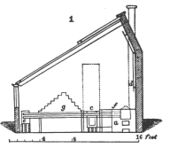

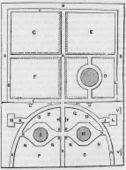

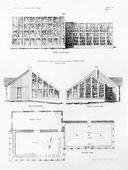

Although plant-keeping structures have been built since antiquity, the modern greenhouse, in which light and temperature could be artificially controlled, was possible only after 1700 when glassmaking improved and glass became cheaper [Fig. 1]. In addition to blowing glass, a pouring process was used by manufacturers. The earliest plant houses, which were called greenhouses in this country, had façades with large window openings that were integrated into a masonry, wood, or stone structure [Fig. 2]. These early buildings were replaced by iron-and-glass houses around the turn of the nineteenth century, which revolutionized greenhouse construction by allowing wide-span and filigree structures that let in more light. [1]

Greenhouse construction, evident as early as John Bartram’s 1739 description of Westover, Va., on the James River, continued through the mid-nineteenth century at sites ranging from elite houses such as Mount Clare, Charles and Margaret Tilghman Carroll’s plantation in Baltimore, to the more modest dwelling and greenhouse advertised for sale in Charleston in 1748. The pervasiveness of the structure reflects an interest in keeping exotic plants, which was a fundamental function of a greenhouse. In addition, the greenhouse allowed the extension of the growing season by providing a supportive environment for starting seeds, ripening fruit, and forcing flowers.

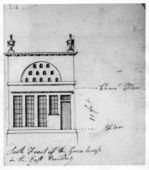

Two major concerns in greenhouse design were the admission of light and the creation of artificial heat. These problems could be solved in the modest construction of a building with a high back wall, a low front wall, and a glazed roof above, as shown in the greenhouse at Kirk Boott’s residence in Boston [Fig. 3]. The brick wall of a greenhouse could also serve as support for trellises or espaliered fruit trees. Most simple greenhouses built in this mode did not require the high temperatures or moist atmosphere of hothouses. As M’Mahon pointed out in 1806, such a greenhouse needed only enough artificial heat to “keep off frost and dispel damps,” whereas the hothouse required an inside stove and more glass (see Conservatory and Hothouse for further discussion of heating systems).

Early greenhouses had brick, stone, or dirt floors, but improved designs later made use of wood floors so that the air space under the floor might allow hot air to radiate under the entire floor. [2] A. J. Downing recommended a small, air-tight coal stove and the related Polmaise mode of heating. This heating technique was based on the recirculation of air in the greenhouse: cold air was drawn into a furnace and heated air was expelled into the farthest reaches of the structure. [3] In 1848, Downing described a plant house for Montgomery Place on the Hudson River that utilized this feature.

Texts

Usage

- Bartram, John, July 18, 1739, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd II, on the James River, Va. (1992: 121) [4]

- “Col Byrd is very prodigal in Gates roads walks hedges & seeders [cedars] trimed finely & A little green house with 2 or 3 [orange] trees . . .”

- Smith, John, 1745, describing Springettsbury, near Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Weber 1996: 46–47) [5]

- “In the afternoon, the weather being so agreeable, John Armitt and I rode to Charles Jenkin’s ferry on Schuykill. We ran and walked a mile or two on the ice. On our way thither we stopped to view the proprietor’s green-house, which at this season is an agreeable sight; the oranges, lemons and citrons were, some green, some ripe, some in blossom.”

- Anonymous, 1748, describing in the South Carolina Gazette a property for sale in Charleston, S.C. (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 167) [6]

- “[The dwelling house contains] a large Garden, with two neat Green Houses for sheltering exotic Fruit-Trees, and Grape-Vines.”

- Fisher, Daniel, 1755, describing the greenhouse in the Proprietor’s Garden, Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Martin 1991: 211) [7]

- “What to me surpassed every thing of the kind I had seen in America was a pretty bricked Green House, out of which was disposed very properly in the Pleasure Garden, a good many Orange, Lemon and Citrous [sic] Trees, in great profusion loaded with abundance of Fruit and some of each sort seemingly then ripe.”

- Médéric Louis Élie Moreau de St.-Méry, March 26, 1797 (quoted in Roberts 1947: 240) [8]

- "I went... to visit Robert Morris’s greenhouse [serre chaud] near Philadelphia. It had very beautiful specimens of orange trees, lemon trees, and pineapples.]

- c. September 6, 1797, A Schedule of Property within the State of Pennsylvania Conveyed by Robert Morris, to the Hon. James Biddle, Esq. And Mr. William Bell, in Trust for the use and account of the Pennsylvania Property Company [9]

- "An Estate called the Hills Situate in the Northern Liberties, near the City of Philadelphia, containing Three hundred acres of land highly improved, and on which are erected a large and elegant greenhouse, with a hot house of fifty feet on each side; on the back front a House for a gardener, with one large and five small rooms, also two large rooms on the back or north front of the hot house, with an excellent vault under the green houses, and a covered room for preserving roots & c in winter; the whole being a strong stone building, with the necessary glasses, casements, fruit trees, plants shrubs & c in good order; a well of excellent water, with a pump close to the north front the whole enclosed within a large Garden stocked with fruit trees of the best kind &c. & c."

Citations

Images

Inscribed

George Washington, Alternate plan (“Plan No. 1”) for the greenhouse at Mount Vernon, n.d.

George Washington, Alternate plan (“Plan No. 2”) for the greenhouse at Mount Vernon, n.d.

Batty Langley, “An Improvement of a beautiful Garden at Twickenham,", in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. IX.

Philip Miller, “The Ground Plan of the Green house” and “The Ground Plan of the two Stoves,” in The Gardeners Dictionary ([1754] 1969), p. 577.

William Halfpenny, “The Plan and Elivation of a Green House in the Chinese Taste,” in Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste (1755), pl. 42.

Samuel Vaughan, Plan of the buildings and grounds of Mount Vernon, 1787.

Andrew Craigie, Proposed Outbuildings for the Craigie Estate, December 11, 1791.

William Dandridge Peck, Plan of the botanic garden of Mr. Curtis, Newbury, Mass., Feb. 19, 1805.

Charles Willson Peale, Letter to Angelica Peale describing his garden at Belfield, November 22, 1815.

J. C. Loudon, Plan, view, and section of green-house, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), p. 811, fig. 567.

J. C. Loudon, Greenhouse or conservatory for a flower-garden, with a span roof, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), p. 811, fig. 568.

Joshua Barney, Map of the Hampton Estate, 1843.

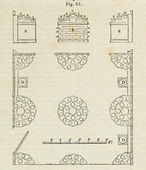

George William Johnson, Floriculture Building, in A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847), p. 230, fig. 51.

Thomas S. Sinclair, "Plan of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane at Philadelphia," in Thomas S. Kirkbride, American Journal of Insanity 4 (April 1848): n.p.

A. J. Downing, Sketch of a “Propagating Pit” (or greenhouse) at Montgomery Place, June 17, 1848.

Anonymous, "Plan of a small Green-House" and "Section of the Same," in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 3, no. 6 (December 1848): figs. 32 and 33.

Anonymous, “Design for a Country House,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 4, no. 6 (December 1849): pl. opp. p. 249.

Anonymous, "A Country House in the Pointed Style," in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. p. 304, figs. 133 and 134.

Frances Palmer, "Design for a Vinery & Green House," in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), vol. 2, pl. 43.

Frances Palmer, "Cottage Villa in the Anglo Swiss Style," in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), vol. 2, pl. 60, design 52.

Frances Palmer, "Cottage Villa in the earliest English Style," in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), vol. 2, pl. 60, design 53.

- 1123.jpg

1887

Associated

Oscar Alexander Lawson, Robert Buist: Nurseryman & Florist, n.d.

Jeremiah Paul, “Robert Morris’ Seat on Schuylkill,” July 20, 1794.

Samuel McIntire, “South Front of the Green house in the East Building," Elias Hasket Derby House, n.d.

John Archibald Woodside, Lemon Hill, 1807.

William Russell Birch, "Woodlands, the Seat of Mr. Wm. Hamilton, Pennsylva.," 1808, in William Russell Birch and Emily Cooperman, The Country Seats of the United States (2009), p. 69, pl. 14.

Hugh Reinagle, Elgin Garden on Fifth Avenue, c. 1812.

Charles Willson Peale, View of the garden at Belfield, 1816.

Robert Squibb, Green-House: front and back walls, in The Gardener’s Calendar for the States of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia (1827), frontispiece.

William Satchwell Leney, View of the Botanic Garden of the State of New York, 1828.

James E. Teschemacher, "A green-house constructed at the centre of a cottage," in Horticultural Register and Gardener's Magazine vol. 1 (May 1, 1835), opp. p. 157.

John Notman, “No. 1 Ground Plan, Smithsonian Institute,” December 23, 1846.

George William Johnson, Flower Pot, in A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847), p. 230, fig. 47.

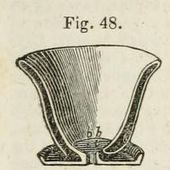

George William Johnson, Flower Pot, in A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847), p. 230, fig. 48.

George William Johnson, Flower Pot, in A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847), p. 230, fig. 49.

George William Johnson, Flower Pot, in A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847), p. 230, fig. 50.

Anonymous, "Design for a Flower Garden," in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 2, no. 12 (June 1848): p. 558, fig. 67.

Anonymous, "Cottage Residence of Wm. H. Aspinwall, Esq.," in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), pl. opp. p. 51, fig. 8.

Anonymous, A Country House in the Pointed Style, in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. p. 304, fig. 133.

Anonymous, “Rural Gothic Villa,” in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. p. 322, fig. 148.

Attributed

John Izard Middleton, Greenhouse, 1813.

Nicolino Calyo, Harlem, the Country House of Dr. Edmondson, 1834.

Joseph Jacques Ramée, Estate plan for Calverton [detail], c. 1816, in Parcs & jardins (c. 1836), pl. 1.

Augustus Weidenbach, Belvedere, c. 1858.

- 1460.jpg

1870s

Notes

- ↑ A disadvantage of cast iron technology was that condensation developed as a result of iron’s high thermal conductivity. Humidity control, always a concern, became a real issue in design. Therese O’Malley, Glasshouses: The Architecture of Light and Air (Bronx, N.Y.: The Garden, 2005) view on Zotero

- ↑ Michael F. Trostel, Mount Clare, Being an Account of the Seat Built by Charles Carroll, Barrister, upon His Lands at Patapsco (Baltimore: National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the State of Maryland, 1981), 120, fn. 2 view on Zotero

- ↑ “Description of the Polmaise Mode of Heating Greenhouses,” Horticulturist 3 (September 1848): 122–27.

- ↑ John Bartram, The Correspondence of John Bartram, 1734-1777, ed. by Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992) view on Zotero

- ↑ Carmen Weber, "The Greenhouse Effect: Gender-Related Traditions in Eighteenth-Century Gardening," in Landscape Archaeology: Reading and Interpreting the American Historical Landscape, ed. by Rebecca Yamin and Karen Bescherer Metheny (Knoxville: The University of Tennesee Press, 1996), 32–51 view on Zotero

- ↑ Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994). View on Zotero

- ↑ Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1991). View on Zotero

- ↑ Kenneth Roberts, and Anna M. Roberts, eds., Moreau de St. Méry’s American Journey, [1793-1798] (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1947) view on Zotero.

- ↑ A Schedule of Property within the State of Pennsylvania Conveyed by Robert Morris, to the Hon. James Biddle, Esq. And Mr. William Bell, in Trust for the use and account of the Pennsylvania Property Company, c. September 6, 1797, Autograph Collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, original MS reproduced Robbins, 1987, 136, view on Zotero.