Hallowell, ME

The village of Hallowell was built on steeply terraced land along the Kennebec River in what is now the state of Maine. The name of the village derived from the Boston merchant and Kennebec Proprietor Benjamin Hallowell, who owned large swathes of property in the area. Several of his heirs had emigrated from England in the late 18th century for the purpose of settling Hallowell.[1] In addition to building basic infrastructure such as roads and stone walls, they dabbled in myriad ventures to attract settlers, improve agriculture, and create economic opportunity.[2]

Overview

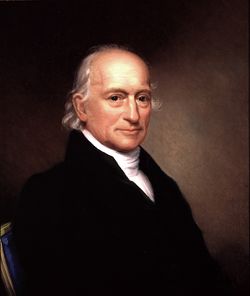

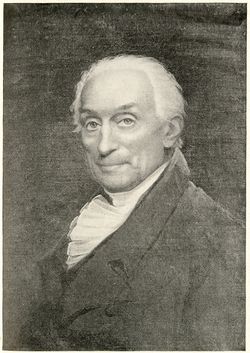

Associated People: Benjamin Hallowell; Samuel Vaughan (1720–1802); Benjamin Vaughan (1751–1835)

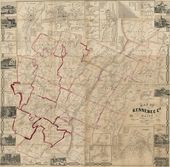

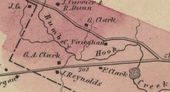

Location: Hallowell, ME

Condition: extant

History

Benjamin Hallowell’s son-in-law, Samuel Vaughan, had been interested in establishing a Unitarian community at Hallowell since about 1784. Ten years later, his son Charles (1759–1839) settled in Hallowell, where he built a large, two-story house fronted by a piazza on a high plateau overlooking the Kennebec River in Hallowell [Fig. 1].[3] John Hannibal Sheppard (1791–1873), who moved to Hallowell as a child in 1793, later recalled the striking appearance of this “White House on the hill”: “False taste had planted no trees on the summit to hide it from the distant view, and it stood out in bold relief to the eye; for sufficient was the back ground of a mountain forest to make a finish in the rural picture.”[4] The house was subsequently occupied and much improved by Charles Vaughan’s elder brother, Dr. Benjamin Vaughan, who immigrated to America in 1797 with the aim of living in rustic simplicity at Hallowell. After surveying the family homestead, however, he confessed himself “agrieved and ashamed that what was designed and ought to have been the model of the country has long been one of its reproaches. I find . . . the whole domain looking like a wretched piece of English common.”[5]

By 1799 Dr. Vaughan had hired the British gardener John Hesketh, who had previously served as head gardener at Lord Derby’s estate, Knowsley Hall, near Liverpool.[6] Capability Brown had designed Knowsley’s kitchen garden and park in the mid-1770s, and his ideas appear to have influenced Hesketh’s landscape work at Hallowell. Dr. Vaughan’s house became renowned for the striking manner in which cultivated flower gardens and orchards near the house were juxtaposed against the seemingly untamed wilderness of the woodland park. Following a visit to Hallowell in 1807, Timothy Dwight praised the “romantic” setting of Vaughan’s house, especially the wilderness, which had been “left absolutely in the state of nature,” with paths “appearing to have been trodden out by the feet of wild animals, [rather] than to have been contrived, and bridges, so rude and inartificial, as to seem the result of accident, rather than the effect of labour.” All this reflected “the best taste,” leading to Dwight’s conclusion, “I know not so handsome an appendage of nature to any gentleman’s seat in this country” (view text).[7]

The gardens at Dr. Vaughan’s house were extensive, occupying several acres. Samuel Lane Boardman (1836–1914), a journalist who grew up near Hallowell, recalled that “Some ten or twelve men were constantly employed in it during the season of growth and besides containing all the most common varieties of vegetables the new sorts imported from Europe were here tested and if they proved valuable disseminated throughout the State.”[8] The flower garden featured “numerous alleys” and “wide walks . . . between slightly raised beds of flowers, interspersed with apple and other fruit trees.”[9] Dr. Vaughan’s grandson, William Manning Vaughan (1807–1891), recalled that in the early 19th century his aunts grew foxglove, narcissus, and roses in the portion of the garden nearest the house, while his grandmother grew herbs—such as peppermint and chamomile—which she distributed for medicinal purposes.[10] An ascending path led to a summerhouse that afforded panoramic views of the village and riverine landscape.[11] Adjoining the gardens was a fruit and nut orchard, and Dr. Vaughan also operated a flourishing commercial nursery. He and his wife were known for their generosity in sharing seeds and cuttings from the garden with the numerous neighbors and international visitors who came to see it.[12] Vaughan’s aesthetic approach to developing the family property evidently riled his brother Charles, who, in 1800, chided that he should focus more exclusively on preparing the land for cultivation—“the more that can be prepared the better, and whether it looks well or ill is no object.”[13]

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Dwight, Timothy, 1807, describing Hallowell, ME (1821–22: 2:218–19)[14]

- “Hallowell is a very pretty town, built on an irregular, or rather steep, descent. This slope, though interrupted, is handsome, and furnishes more good building spots, than if it had been an uniform declivity, and at the same time equally steep. Then all the grounds would have descended too rapidly. Now they furnish a succession of level surfaces for gardens, house-plats and court yards; and are thus very convenient, as well as sometimes very handsome. The streets are both parallel, and right-angled to the river; but, like those of all other towns throughout this country, are irregular. The houses, being generally new and decent, have the same cheerful appearance, which has been so often remarked. Several of them are handsome, and surrounded by very neat appendages. All the situations on the higher grounds are fine. A more romantic spot is not often found, than that on which stands the house of Mr. [Benjamin] V[aughan]. a descendant of Mr. Hallowell, from whom this town took its name; inheriting from him, it is said, a large landed estate in this country. . . . His house stands on one of the elevated levels, mentioned above, where the hill, bends from its general Southern direction toward the West, and, forming an obtuse, circular point, furnishes a beautiful Southern, as well as Northern and Eastern, prospect. The river, here lying almost immediately below the eye, is a noble object.

- “In the rear, as you recede from the river, but at the side of the house, (the front being Southward, and looking down the river;) lies a handsome garden, furnishing even at this time of the year, ample proofs of the fertility of the soil. Behind the garden is a wild and solitary valley; at the bottom of which runs a small mill stream. Its bed is formed, universally, of rocks and stones. In three successive instances strata of rocks cross the stream obliquely; and present a face so nearly perpendicular, as to furnish in each instance, a charming cascade. These succeed each other at distances conveniently near; and yet so great, that one of them only can be seen at a time. The remaining course of the stream is an alternation of currents, and handsome basins. On either side, the banks, which are of considerable height, and sometimes steep, formed of rude forested grounds, and moss-grown rocks, are left absolutely in the state of nature. Along the brook Mr. [Benjamin] V[aughan]. has made a convenient foot-way, rather appearing to have been trodden out by the feet of wild animals, than to have been contrived by man, and winding over a succession of stone bridges, so rude and inartificial, as to seem the result of accident, rather than the effect of human labour. With these little exceptions, the whole scene is left, with the best taste, as it was found. A charming change from the cheerfulness of the house, garden and town, and the splendour of the river and its shores, is here experienced in a moment. The first step out of the rear of the garden is into wildness, solitude, and gloom. I know not so handsome an appendage of nature to any gentleman’s seat in this country.”

- Sheppard, John H., 1865, describing the garden of Benjamin Vaughan (1865: 14)[15]

- “Dr. Benjamin Vaughan was fond of horticulture, and was one of the pioneers of New England in the improvement of fruits and cereals. He imported choice seeds, which he was ever ready to impart to his neighbors. He had a large garden of several acres tastily laid out, with broad paths and numerous alleys, whose borders were adorned with flowers or shaded with currant bushes, fruit trees and shrubbery. The whole was under the care of an English gardener. Every kind of culinary vegetable was raised abundantly. . . .

- “I spoke of his garden; there may be many costly and more embellished, owned by millionaires, in the vicinity of our great cities; but this of Dr. Vaughan had one charm, seldom found elsewhere. It lay in the midst of a landscape of surpassing beauty. It rose gradually from the entrance gate near the house, until in ascending the walk you found yourself on the height of a declivity at the verge of tall woods in a summer-house; from this airy resting-place there was a magnificent view of the village, distant hills, and the gentle waters of the Kennebec winding "at their own sweet will.” Near the spot were mowing fields, and pastures with cattle grazing and some shady oaks yet spared by the Goths in their clearings. . . .

- “Behind the summer-house loomed up a steep mountain deeply wooded, and between them was a precipitous ravine or narrow glen through which a powerful stream rushed headlong from ledge to ledge, beneath a dark shadow of tall trees, until it leaped down like a miniature cataract and formed a prettybasin, where we sometimes caught a small trout or two. After descending from rock to rock the stream at last subsided into a pond, which supplied the large flour mill built by Mr. Charles Vaughan. This romantic waterfall was called the “Cascade,” accessible by a winding path down the steep, and its murmur could be heard from the summer-house in the stillness of the evening, where now the steam-whistle and the locomotive echo through the valley below. Perhaps the utilitarian, who only thinks what his berries may bring in the market, or how a cabbage shall add another dime to his dollars, may ridicule the idea of fine scenery surrounding a garden.”

Images

Other Resources

Library of Congress Authority File

“The Search for Benjamin’s Garden: A History Mystery,” Vaughan Homestead Foundation Website

Notes

- ↑ Craig Compton Murray, “Benjamin Vaughan (1751–1835): The Life of an Anglo-American Intellectual” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1989), 204–5, 381–82, view on Zotero; Samuel L. Boardman, “A General View of the Agriculture and Industry of the County of Kennebec, with Notes upon Its History and Natural History,” in Tenth Annual Report of the Secretary of the Maine Board of Agriculture (Augusta, ME: Stevens & Sayward, Printers to the State, 1865) 10: 130, 187, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Emma Huntington Nason, Old Hallowell on the Kennebec (Augusta, ME: Press of Burleigh & Flynt, 1909), 30, view on Zotero; Boardman, 1865), 10: 190,view on Zotero.

- ↑ John H. Sheppard, Reminiscences of the Vaughan Family, and More Particularly of Benjamin Vaughan, LL.D. (Boston: David Clapp & Son, 1865), 10, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sheppard 1865, 16, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Murray 1989, 384, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Lane Boardman, “Appendix to Report on Kennebec County,” in Twelfth Annual Report of the Secretary of the Maine Board of Agriculture (Augusta, ME: Stevens & Sayward, Printers to the State, 1867), 220, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Dwight 1821, 2: 218, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Boardman 1865, 189–90, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Warren Vaughan, Hallowell Memories (Hallowell, ME: Privately printed, 1931), 46–40, view on Zotero; Sheppard 1865, 14, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Warren Vaughan interview of 1891 quoted on Vaughan Homestead Foundation website.

- ↑ Sheppard 1865, 14, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Boardman 1865, 190, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Murray 1989, 387, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Dwight 1821–22, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sheppard 1865, view on Zotero.