Ha-Ha/Sunk fence

(Ah Ah, Ah-ha, Foss, Fosse, Ha ha, Ha! Haw)

See also: Deer park

History

From the early 18th century to the mid-19th century, treatises praised the ha-ha as a useful design solution for the construction of barriers without interrupting views.[1] Several writers recall the origin of the name as the expression of surprise at finding a sudden and unperceived check to one’s walk. A ha-ha, also known as a sunk fence, blind fence, ditch and fence, deer wall, or foss, was formed by a ditch (sometimes with a fence at its lowest point), a steep bank, or a wall built into the side of a hill. Whatever the method of construction, the ha-ha created a barrier that was not visible from one side or, if a ditch, all directions. Anthony St. John Baker’s 1827 sketch of Riversdale, in Maryland, illustrates a ha-ha wall built into the ground that created a barrier while permitting unobstructed views from the house [Fig. 1].[2] The deer depicted in the foreground underscore the function of the feature: to keep a pasture or a park separate from the lawn and garden near a house (see Deer park).

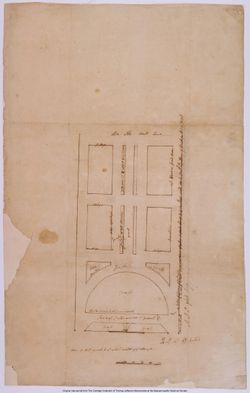

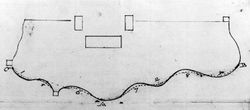

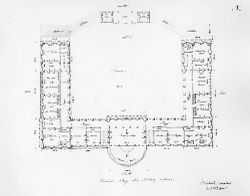

Despite the broad date range of treatise recommendations, usage records suggest that in American practice most of these features were constructed in the late 18th century and that they were exceptional, although notable. The feature seems to have been limited to the estates of the landed elite and larger institutions. Ha-has at John Penn’s estate in Philadelphia; Rosewell in Virginia [Fig. 2]; Mount Vernon; Monticello; Benjamin Henry Latrobe’s plan for a military school [Fig. 3]; and The Woodlands, near Philadelphia, were all constructed in the last quarter of the 18th century. Monticello’s landscape improvements extended into the first decade of the 19th, and an image of Park House in Albion, Illinois, shows a ha-ha dating to around 1820 [Fig. 4]. These sites were among the most elaborate in America in their landscaping programs. George Flower’s ha-ha at Park House, which permitted a view of reclining cattle and grazing sheep, conformed to the notion that Flower’s “success allowed him to live a life approximating that of an English country gentleman.”[3]

The ha-ha seems to have been used at the edge of lawns and gardens to separate the spaces immediately surrounding the dwelling from pasture land and grazing animals. Mount Vernon’s ha-ha, which George Washington referred to as both a “ha haw” and a deer wall, separated the west lawn from the deer park below, leaving a clear view from the house to the Potomac River and distant Maryland shore. At Monticello, Thomas Jefferson took advantage of the mountain’s high topographic relief by building his ha-ha into the hillside along the southern side of his newly leveled lawn using a retaining wall of stone. This ha-ha (elsewhere called a terrace wall), allowed views of the panorama beyond and screened much of the working area along Mulberry Row when viewed from the house and lawn. John Nancarrow’s plan of John Penn’s estate, now the site of the Philadelphia Zoo, also indicates placement of a ha-ha at the edge of the pleasure ground, in this case just along the southern border of his property [Fig. 5].

A visitor to Monticello in 1823, who lacked the vocabulary to describe what he saw, wrote, “As we approached the house we rode along a fence which was the only one of the kind I ever saw. Instead of being upright, it lay upon the ground across a ditch, the banks of the ditch raised the rails a foot or two above the ground on each side of the ditch so that no kind of grazing animals could easily cross it, because their feet would slip between the rails. It had just the appearance of a common post and rail straight fence, blown down across a ditch.”[4] Several explanations may be posited for the limited appearance of the ha-ha in America as compared with its more prevalent use in Britain. One explanation may be that large-scale landscape gardens and parks associated with ha-has were less common in America (see English style). A ha-ha not only required the space to create the feature and a garden of proportions to match, but also involved an expenditure of labor and materials. Jefferson’s notes from 1804 express his concern with cost savings as he planned to reuse stone from other parts of the plantation to construct the masonry section of his ha-ha.[5] Perhaps the aesthetic of the uninterrupted view was not sufficiently compelling among the majority of landowners to warrant the expense and effort of the ha-ha.

The seeming tolerance and incorporation of fences into landscape designs of even the most “naturalistic” style may explain the infrequent mention of this feature (see Fence). The ha-ha was not effective as a barrier against deer, a major threat to garden vegetation in much of the country. While the sunken fences were a deterrent to grazing animals such as cattle and sheep, it took fences such as the ten-foot-high paling fence that Jefferson constructed around his kitchen garden to keep out deer.[6] In addition, in the late 18th century, when the ha-ha was most often utilized, many plantations had separate farms, or “quarters,” where the more intensive agricultural and animal production took place far enough from the main house and its adjacent gardens to eliminate worry of stray animals (see Plantation). The pastoral image of farm animals lying just beyond the reach of the lawn or sheep grazing at the edge of the ha-ha still evoked an agrarian ideal as late as 1849 in A. J. Downing's writings, but by that time the appeal of the ha-ha was largely aesthetic and symbolic, rather than practical (view text).

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Washington, George, 1785, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (Jackson and Twohig, eds., 1978: 4:86; Johnson 1953: 100)[7][8]

- “[February 8] Finding that I should be very late in preparing my Walks & Shrubberies if I waited till the ground should be uncovered by the dissolution of the Snow—I had it removed Where necessary & began to Wheel dirt into the Ha! Haws &ca.—tho' it was it exceeding miry & bad working. . . [Fig. 6]

- “[March 11] Planted. . . 13 Yellow Willow trees alternately along the Post and Rail fence from the Kitchen to the South ha-haw and from the Servants’ Hall to the Smith’s Shop.”

- Hamilton, William, September 30, 1785, in a letter to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia (quoted in Madsen 1988: A3)[9]

- “Step also the Diameter of the circle or ring that encloses the Ice House Hill & tell me the space from one to the other side of the walk & of the Ha.Ha.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, April 2–14, 1786, describing the garden at Stowe in Buckinghamshire, England (Oberg and Looney, eds., 2008: 371)[10]

- “The inclosure is entirely by ha! ha!”

- Hamilton, Alexander, 1803, describing Hamilton Grange, estate of Alexander Hamilton, New York, NY (quoted in Lockwood 1931: 1:263)[11]

- “It has always appeared to me that the ground on which our orchard stands is much too moist. To cure this, a ditch round it would be useful, perhaps with a sunken fence as a guard.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, c. 1804, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (quoted in Nichols and Griswold 1978: 107)[12]

- “General ideas for the improvement of Monticello

- “all the houses on the Mulberry walk to be taken away, except the stone house. . . and a ha! ha! instead of the paling along it for an inclosure. This will of course be made when the garden is levelled, and stone for the wall will be got out of the garden itself, in digging, aided by that got out of the level in front of the S.W. offices, the old stone fence below the stable, and the lower wall of the garden, which is thicker than necessary.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., April 1848, describing the pleasure grounds and farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia (American Journal of Insanity 4: 349)[13]

- “Between the north lodge and the deer-park, separated from the latter by a sunk palisade fence, is a neat flower garden.”

Citations

- Dezallier d’Argenville, Antoine-Joseph, 1712, The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712: 77)[14]

- “At present we frequently make Thorough-Views, call’d Ah, Ah, which are Openings in the Walls, without Grills, to the very Level of the Walks, with a large and deep Ditch at the Foot of them, lined on both Sides to sustain the Earth, and prevent the getting over, which surprises the Eye upon coming near it, and makes one cry, Ah! Ah! from whence it take its Name.”

- Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce, 1769, The Complete Farmer (1769: n.p.)

- “The boundaries of these gardens flower gardens, whatever they are fenced with, should be carefully concealed with plantations of flowering shrubs, intermixed with laurels and other evergreens to cover the fences, which have a disagreeable appearance, when they are left naked and exposed. Nor should all the boundaries be seen from any one point of view; and if the country around affords a variety of pleasing prospects, it will be right to bound the pleasure-garden with an ha-ha ditch and wall, to lay these views open to sight.”

- Walpole, Horace, 1770, “On Modern Gardening” (1876: 3:80–81)[15]

- “I have observed in the garden at Gubbins, in Hertforshire, many detached thoughts, that strongly indicate the dawn of modern taste. As his reformation gained footing, he ventured farther, and in the royal garden at Richmond dared to introduce cultivated fields, and even morsels of a forest appearance, by the sides of those endless and tiresome walks, that stretched out of one into another without intermission. But this was not till other innovators had broke loose too from rigid symmetry. But the capital stroke, the leading step to all that has followed, was [I believe the first thought was Bridgman’s] the destruction of walls for boundaries, and the invention of fossés—an attempt then deemed so astonishing that the common people called them Ha! Ha’s! to express their surprise at finding a sudden and unperceived check to their walk.

- “One of the first gardens planted in this simple, though still formal style, was my father’s at Houghton. It was laid out by Mr. Eyre, an imitator of Bridgman. It contains three-and-twenty acres, then reckoned a considerable portion.

- “I call a sunk fence the leading step, for these reasons: No sooner was this simple enchantment made, than leveling, moving and rolling, followed. The contiguous ground of the park, without the sunk fence, was to be harmonized with the lawn within; and the garden in its turn was to be set free from its prim regularity, that it might assort with the wilder country without. The sunk fence ascertained the specific garden; but that it might not draw too obvious a line of distinction between the neat and the rude, the contiguous out-lying parts came to be included in a kind of general design: and when nature was taken into the plan, under improvements, every step that was made pointed out new beauties and inspired new ideas. At that moment appeared Kent, painter enough to taste the charms of landscape, bold and opinionative enough to dare and to dictate, and born with a genius to strike out a great system from the twilight of imperfect essays. He leaped the fence, and saw that all nature was a garden. He felt the delicious contrast of hill and valley changing imperceptibly into each other, tasted the beauty of the gentle swell or concave scoop, and remarked how loose groves crowned an easy eminence with happy ornament; and while they called in the distant view between their graceful stems, removed and extended the perspective by delusive comparison.”

- Anonymous, 1798, Encyclopaedia (1798: 7:549)[16]

- “[According to Bridgeman] ‘But the capital stroke, the leading step to all that has followed, was the destruction of walls for boundaries, and the invention of fosses—an attempt then deemed so astonishing, that the common people called them Ha! Ha’s! to express their surprise at finding a sudden and unperceived check to their walk.’

- “'A sunk fence may be called the leading step, for these reasons. No sooner was this simple enchantment made, than levelling, mowing, and rolling, followed. The contiguous ground of the park without the sunk fence was to be harmonized with the lawn within; and the garden in its turn was to be set free from its prim regularity, that it might assort with the wilder country without. The sunk fence ascertained the specific garden; but that it might not draw too obvious a line of distinction between the neat and the rude, the contiguous out-lying parts came to be included in a kind of general design; and when nature was taken into the plan, under improvements, every step that was made pointed out new beauties, and inspired new ideas.’”

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803: 13, 81)[17]

- “There is no error more prevalent in modern gardening, or more frequently carried to excess, than taking away hedges to unite many small fields into one extensive and naked lawn, before plantations are made to give it the appearance of a park; and where ground is subdivided by sunk fences, imaginary freedom is dearly purchased at the expence of actual confinement. . .

- “3. A third method [of concealing a boundary fence] is, sinking the fence below the surface of the ground, by which means the view is not impeded, and the continuity of lawn is well preserved. . . We must therefore so dispose a fosse, or ha! ha! that we may look across it and not along it. For this reason a sunk fence must be straight and not curving, and it should be short, else the imaginary freedom is dearly bought by the actual confinement, since nothing is so difficult to pass as a deep sunk fence.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (1806: 65)[18]

- “A Foss or ha-ha, is often formed at the termination of a spacious lawn, grand walk, avenue, or other principal part or parts of the pleasure ground, both to extend the prospect into the adjacent fields and country, and give these particular parts of the ground an air of larger extent than they really have; as at a distance nothing of this kind of fence is seen, so that the adjacent fields, plantations, &c. appear to be connected with, or but a continuation of the pleasure ground.

- “A Foss or ha-ha, is a sunk fence, ditch-like, five or six feet deep, and ten, twenty, or more wide; and is made in different ways according to the nature of the ground. One sort is formed with a nearly upright side next the pleasure ground, five, six, or seven feet deep, faced with a wall of brick, or stone, or strong post and planking, &c. . . the other side is made sloping outward gradually from the bottom of said wall, till it terminates as near a level as possible.

- “Another kind of foss is formed with both sides sloping, and in perpendicular depth from four to five or six feet, having a fence near that height arranged along the bottom, formed of strong paling, or any kind of palisado-work; the sides may be sloped gradually from the bottom to ten or twenty feet width, or more at top, but sloped more to the field side than to the other.”

- Nicol, Walter, 1823, The Villa-Garden Directory (1823: 4–5)[19]

- “Next to the error of rearing high fences, is that of bounding the whole premises by a close and connected belt of shrubbry, or other plantation; leaving the house standing in a small open paddock, unadorned by a plant of any kind; the belt being often separated from it by a deep and broad ditch, or ha-ha.

- “This style is no doubt in imitation of that of the park; and the reason, probably, why we have not clumps and groups of trees here as in a park, is, that the belt is sufficiently near to the house, either for shelter, or to be admired for its variety. In a spot of a few acres, however, this style cannot be admitted with any degree of propriety. In the first place, you cannot look from a window without looking into a ditch which must convey an idea of restraint and confinement, very unpleasant. Next, the small formal lawn, if it may be so called, seems a perfect "dish", with as formal an edging; and, from no point can a view of distant objects be had, without being interrupted by this edging; which is perplexing to the eye, in a great measure, although the situation of the house may be such as to admit of looking over it.

- “The sunk fence can only be admissible in the front ground of a Villa, when placed in such a manner as to cross the view from the windows, and it may be useful in dividing the lawn in that way, if it be of any considerable extent; but a light moveable railing, consisting of fleaks or hurdles, will be found to answer the purpose better, as with these the ground can be divided in any shape or proportion, at pleasure.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 279)[20]

- “HA-HA, is a sunk fence, being placed at the bottom of a deep and spreading ditch, either to avoid any interruption to an expanse of surface, or to let in a desired prospect. As all deceptions are unsatisfactory to good taste, and as when viewed lengthwise these fences are formal and displeasing, they ought never to be adopted except in extreme cases.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849: 346),[21]

- “The sunken fence, fosse, or ha-ha, is an English invention, used in separating that portion of the lawn near the house, from the part grazed by deer or cattle, and is only a ditch sufficiently wide and deep to render communication difficult on opposite sides. When the ground slopes from the house, such a sunk fence is invisible to a person near the latter, and answers the purpose of a barrier without being in the least obtrusive.” back up to History

Images

Inscribed

John Nancarrow, Plan of the Seat of John Penn, jun:r Esq:r in Blockley Township and County of Philadelphia, 1790. The “Ah-ha” at “h” is designated by the linear feature located at the lower edge of the plan above the word “Land.”

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Military academy. Principal story, floor plan, 1800. “Haha” is indicated at the top linking the wings with the central building.

Associated

Samuel Vaughan, Plan of the buildings and grounds of Mount Vernon, 1787.

Edward Savage, The East Front of Mount Vernon, c. 1787–92.

George Washington, Drawing and Notes for a Ha-Ha Wall at Mount Vernon, October 1798, 1798.

Attributed

Anthony St. John Baker (artist), B. King (lithograper), Riversdale, near Bladensburg, 1827.

Notes

- ↑ As Steven A. Mansbach relates in his brief survey of the history of the ha-ha in England, the term entered English garden literature with John James’s 1712 translation of Dézallier d’Argenville’s La théorie et la practique du jardinage (1709). Charles Bridgeman, Lord Cobham’s head gardener at Stowe, employed the ha-ha in the extensive enlargement of the gardens in the 1720s. See Steven A. Mansbach, “An Earthwork of Surprise: The 18th-Century Ha-Ha,” Art Journal 42, no. 3 (Fall 1982): 217–21, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Like similar barriers at Mount Vernon and Monticello, the Riversdale wall was ineffective at deterring deer, and Rosalie Calvert Stier complained that deer were eating tulips under her windows. She, unfortunately, failed to mention the wall so we do not know whether she referred to it as a ha-ha (Margaret Law Calcott, personal communication).

- ↑ Judith A. Barter and Lynn E. Springer, Currents of Expansion: Painting in the Midwest, 1820–1940 (St. Louis, MO: St. Louis Art Museum, 1977), 40, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Silvio A. Bedini, Thomas Jefferson: Statesman of Science (New York: Macmillan, 1990), 410, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Kelso, Kingsmill Plantations, 1619–1800: Archaeology of Country Life in Colonial Virginia (Orlando, FL: Academic Press, 1984), 167, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), 377, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, eds., The Diaries of George Washington, 6 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1978), vol. 4, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gerald W. Johnson, Mount Vernon: The Story of a Shrine (New York: Random House, 1953), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Karen Madsen, “William Hamilton’s Woodlands,” (paper presented for seminar in American Landscape, 1790–1900, instructed by E. McPeck, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Barbara B. Oberg and J. Jefferson Looney, eds., “Notes of a Tour of English Gardens, [April 2–14,] 1786,” in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson Digital Edition (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alice B. Lockwood, ed., Gardens of Colony and State: Gardens and Gardeners of the American Colonies and of the Republic before 1840, 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s for the Garden Club of America, 1931), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Doveton Nichols and Ralph E. Griswold, Thomas Jefferson, Landscape Architect (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1978), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, “Description of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, with Remarks,” American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4 (April 1848): 347–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A.-J. (Antoine Joseph) Dézallier d’Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening; Wherein Is Fully Handled All That Relates to Fine Gardens, . . . Containing Divers Plans, and General Dispositions of Gardens, trans. John James (London: Geo. James, 1712), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Horace Walpole, “On Modern Gardening,” in Anecdotes of Painting in England; with Some Account of the Principal Artists, ed. Ralph N. Wornum (London: Chatto and Windus, 1876), 3:63–93, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia, or A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature, 18 vols. (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1798), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M’Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done. . . for Every Month of the Year (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter Nicol, The Villa-Garden Directory, or Monthly Index of Word, to Be Done in Town and Villa Gardens, Shrubberies and Parterres (Edinburgh: Archibald Constable, 1823), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America. . . , 4th ed. (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1849), view on Zotero.