Humphry Marshall’s Botanic Garden

Humphry Marshall’s Botanic Garden, located in Chester County, Pennsylvania, near the present town of Marshallton, was one of the earliest botanical gardens in America and the site of extensive plant and seed exchanges among the American colonies and between America and Europe.

Overview

Alternate Names: Marshall’s Garden; Marshall’s Arboretum; Botany Farm; Marshallton

Site Dates: 1773–1813

Site Owner(s): Humphry Marshall (1722–1801); Moses Marshall (1758–1813); Chester County Historical Society

Location: Marshallton, PA

Condition: demolished

View on Google maps

History

The first botanic garden developed by Humphry Marshall was located on his father’s property near the fork of the Brandywine creek in Chester County, Pennsylvania. That garden was laid out in the mid-18th century with seeds and plants Marshall gathered during expeditions into the surrounding countryside or received from friends and correspondents in America and Europe.[1] Along with his cousin John Bartram, Marshall was an active dealer in plants and seeds in America and many of the plants he cultivated were for commercial export to overseas customers. One of Marshall's most dedicated correspondents, the English Quaker physician and plant collector John Fothergill (1712–1780), repeatedly urged him to set aside a portion of the garden for nursing plants prior to sending them across the Atlantic.[2] Marshall continually sought to expand his foreign client base, and it may have been with the expectation of an enlarged trade that he purchased, in December 1772, thirty acres of land near his father’s farm. Soon thereafter he began laying out a second botanic garden, more extensive than the first, on two to three of acres of the property.[3] Part of the garden functioned as a nursery for the cultivation of plants and seeds intended for commercial botanical exchange. Historical analysis has determined that the property also contained a kitchen garden, pleasure ground, and greenhouse, and that Marshall cultivated trees and shrubs, herbaceous perennials (both indigenous and exotic), and plants valuable for their medicinal or economic utility.[4]

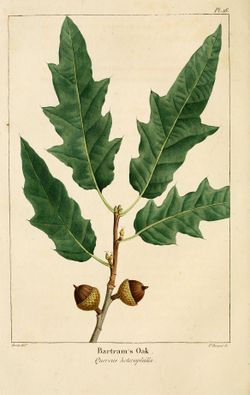

Marshall expanded the range of trees, shrubs, and plants in his garden through a variety of means: personal exploration of surrounding areas, by commissioning friends and relatives (particularly his nephew Moses Marshall) to collect plants and seeds on their travels, and through exchange with other gardeners. From the botanic garden of his cousin John Bartram, Marshall acquired Bartram Yellow Oak (Quercus heterophilla) [Fig. 1] and Winter Aconite.[5] Many of the plants in Marshall's garden were first cultivated there, and some were described for the first time in Marshall's pioneering catalogue of indigenous forest trees and shrubs, Arbustum Americanum: The American Grove, published in 1785.[6] Examples include Sugar Maple, identified by Marshall as Acer saccharum,[7] and despite subsequent variation and confusion in the nomenclature by others (including François André Michaux; [Fig. 2]), known today as "Acer saccharum Marsh.”[8] Sugar Maples were among the original plantings identified on the premises of Marshall's garden in the late 1980s, along with Yellow Buckeye (Aesculus flava), Cucumber Magnolia (Magnolia acuminata), Winter Aconite (Eranthus hyemalis), and three varieties of boxwood, constituting the “largest surviving original colonial American botanic garden planting.”[9]

Having trained as a stone mason, Marshall began constructing a two-and-a-half story house on his new property in the summer of 1773, moving his family there in 1774 [Fig. 3]. The house included a small hothouse warmed by a fireplace, where he cultivated delicate plants, and a botanical laboratory on the second floor where specimens were pressed, sketched, mounted, and classified in Latin descriptions.[10] The William Darlington Herbarium at West Chester State University reportedly contains many specimens from Marshall's garden.[11] The second floor of Marshall's house included a small observatory for his astronomical studies.[12] His “Observations on the Spots of the Sun” was presented to the Royal Society in London by Marshall's friend Benjamin Franklin in 1773.[13]

After Marshall's death in 1801, the property passed to his wife, and then to Moses Marshall, who continued to supply requests for plants but apparently without maintaining the garden to a high standard. Frederick Pursh, whom the elderly Humphry Marshall had conducted through the garden in 1799, reported in 1814 that it was “now very much on the decline, only a few old established trees being left as a memento of what formerly deserved the name of a respectable botanic garden” (view text). The grounds were harvested for the benefit of other gardens in the vicinity. By 1830 Samuel Peirce was making annual collections of seeds and plants (including horse-chestnuts and magnolia seeds) to cultivate at Peirces Park in nearby Marshallton (view text). Throughout the 19th century, Marshall's garden was steadily overtaken by trees and shrubs. That change, together with his association with Arbustum Americanum, resulted in the altered perception of his property as an arboretum rather than a botanic garden.[14] In 1982 the property was acquired by the Chester County Historical Society.

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Fothergill, John, March 2, 1767, letter from London to Humphry Marshall (Darlington 1849: 495)[15]

- “As it may suit thy other concerns, I should be glad if thou would proceed to collect the seeds of other American shrubs and plants, as they fall in thy way; and if thou meets with any curious plant or shrub, transplant it at a proper time into thy garden, let it grow there a year or two; it may then be taken up in autumn, its roots wrapped in a little moss, and laid in a coarse box.”

- Fothergill, John, October 29, 1768, letter from London to Humphry Marshall (Darlington 1849: 497–98)[15]

- “As it may fall in thy way, I should be glad thou would continue thy care in collecting for me such seeds and plants as I have not hitherto received from thee; and I think it would be worth while to sow a part of all the seeds thou gathers, in thy own garden, or some little convenient spot provided for the purpose. There are many curious seeds that lose the property of vegetation by a sea-voyage. The plants thus raised by seed at home, might be removed from the bed they were sown on, the second autumn, or spring following, into boxes of earth, and sent to us in the spring, so as to arrive here in the third or fourth month, and would then succeed very well.”

- Fothergill, John, January 25, 1769, letter from London to Humphry Marshall (Darlington 1849: 499–500)[15]

- “Please to remember to raise a few of all the curious plants whose seeds occur to thee, and send here, and some of the seeds likewise, together with any account thou can collect of their real virtues and uses.”

- Fothergill, John, August 23, 1775, letter from Cheshire to Humphry Marshall (Darlington 1849: 513–15)[15]

- “At present, I cannot expect anything, as all intercourse between America and Britain will be cut off, and I am afraid for a long time. Be attentive, however, to increase thy collection at home, by putting every rare plant thou meets with in a little garden, and as much like their natural situation, as to shade, dryness or moisture, as possible. For instance, most of the Ferns like shade and moisture; these may be planted on some north border, where the sun shines but little except in the morning; and so of the rest.”

- Pursh, Frederick, 1814, recalling a visit to Marshallton in 1799 (1814: 1:vi)[16] back up to history

- “My first object, after my arrival in America, was to form an acquaintance with all those interested in the study of Botany. . . .

- “I next visited the old established gardens of Mr. Marshall, author of a small “Treatise on the Forest-Trees of North America.” This gentleman, though then far advanced in age and deprived of his eye-sight, conducted me personally through his collection of interesting trees and shrubs, pointing out many which were then new to me, which strongly proved his attachment and application to the science in former years, when his vigour of mind and eye-sight were in full power. This establishment, since the death of Mr. Marshall, (which happened a few years ago,) has been, in some respects, kept up by the family but is now very much on the decline, only a few old established trees being left as a memento of what formerly deserved the name of a respectable botanic garden.”

- Anonymous, May 10, 1828, history of Humphry Marshall’s botanic garden, “Chester County Cabinet of Natural Science” (Register of Pennsylvania 1: 302–3)[17]

- “In the year 1774, the late Humphrey [sic] Marshall established his Botanic Garden, at Marshallton: he applied himself very diligently to the improvement of the place, and to the collection of plants, especially such as were indigenous to the United States. The Garden soon obtained a reputation; and for many years before the death of Mr. Marshall, it had become an object of curiosity to men of science: Mr. Frederick Pursh informs us, that it was the first place of a Botanical character visited by him, after his arrival in America. After the decease of Mr. Humphrey Marshall, in the year 1801, we believe that no improvements were made in the garden, and since the death of Doctor Moses Marshall, in 1813, the Botany of the place seems to have been entirely neglected. But it still exhibits many interesting relics, as pine and fir trees—the willow leaved and English oaks, the Kentucky nickar tree, the buckeye, and several species of magnolia. The trees we have mentioned, with various interesting shrubs and herbaceous plants, which survive the general ruin, are memorials of the interest which was formerly taken in the garden by its venerable founder. . . .

- “The science of plants was his favourite study, and before he established his botanic garden, at Marshallton, he had cultivated one on a smaller scale, on the plantation now occupied by Joshua Marshall.”

- Marshall, Mary, 1830, letter from written Humphry Marshall’s Botanic Garden (Gutowski 1988: 119)[18] back up to history

- “Samuel Peirce was here last week, making his usual fall collection of seeds & plants; he gathered Horse-chestnuts, Magnolia Seeds &c.”

- Rafinesque, Constantine Samuel, 1836, describing visits to Pennsylvania gardens during the summers of 1802 and 1804 (1836: 15, 22)[19]

- “On our return to Germantown I studied all the plants of that locality, describing them all minutely. I went also fishing and hunting, and described the birds, reptiles, fishes, &c. An excursion to Westchester was taken with Col. F. [Forrest] to see Marshall’s Botanic garden, and we returned by Norristown. We visited also BARTRAM’S Botanic garden and several other places. . . .

- “I went to see again Mr. Marshall at Westchester, and visited with him the singular magnesian rocks, where alone grow the Phemeranthus or Talinum teretifolium.”

- Darlington, William, 1837, Flora Cestrica (1837: 138, 359, 405)[20]

- “CAROLINIAN SOLANUM. . . . This is a vile, pernicious weed; and extremely difficult to subdue, or eradicate. It is believed to have been introduced by the late Humphrey [sic] Marshall, into his Botanic Garden at Marshallton,—whence it has spread around the neighborhood; and strongly illustrates the necessity of caution, in the introduction of mere Botanical curiosities into good agricultural districts.

- “MARRUBIUM-LIKE LEONURUS. . . . This foreign has probably escaped from the Botanic Garden of the late HUMPHREY [sic] MARSHALL, and bids fair to become extensively naturalized in the surrounding country.

- “M. LUPULINA, L. . . . This is an introduced plant; and not generally naturalized in this County. I am not certain that I have observed it, except in the vicinity of the late Humphrey [sic] Marshall’s Botanic Garden.”

- Darlington, William, 1849, describing Marshallton, estate of Humphry Marshall, West Chester, PA (1849: 22, 487–88, 490–91)[15]

- “In 1773, the second botanical garden within the British provinces of North America, was established by Humphry Marshall, in the township of West Bradford, Chester County, Pennsylvania, at the site of the present village of Marshallton. Humphry, however, had been previously indulging his taste, and employing his leisure time in collecting and cultivating useful and ornamental plants at his paternal residence, near the Brandywine. . . .

- “In 1764, it became expedient to enlarge the dwelling in which he resided with his parents. This addition was built of brick; and the entire work of digging and tempering the clay, making and burning the bricks, and building the walls, was performed by Humphry himself. He also erected a green-house, adjoining the dwelling; which was, doubtless, the first conservatory of the kind ever seen, or thought of, in the county of Chester.

- “The Botanic Garden, at Marshallton, was planned and commenced in the year 1773, and soon became the recipient of the most interesting trees and shrubs of our country, together with many curious exotics; and also of a numerous collection of our native herbaceous plants. A large portion of these yet survive, although the garden, from neglect, has become a mere wilderness; while a number of our noble forest trees, such as Oaks, Pines, and Magnolias (especially the Magnolia acuminata), all planted by the hands of the venerable founder, have now attained to a majestic altitude.

- “For several years prior to the establishment of the Marshallton Garden, Humphry had been much engaged in collecting native plants and seeds, and shipping them to Europe; but after that event, being aided by his nephew, Dr. Moses Marshall, he greatly extended his operations, and directed his attention with enhanced zeal and energy to the business of exploring, and making known abroad, the vegetable treasures of these United States. The present generation of botanists have but an imperfect idea of the services rendered to the science, by the skill and laborious industry of those faithful pioneers; but the letters here given, will show that they contributed largely to the knowledge of American plants.

- “His sight . . . was never so entirely lost, but that he could discern the walks in his garden, examine his trees, and recognise the localities of his favourite plants. In tracing those walks with his friends, pointing out the botanical curiosities, and reciting their history, he took the greatest delight to the last.”

- Darlington, William, September 10, 1849, letter to John Bohlen (quoted in Belden 1965: 111–12)[21]

- “The Garden, as I have told you, was established in the year 1773—Seventy six years ago; and some of the trees have, in that time, attained to a most majestic size—especially some of the Oaks, Pines, and Magnolias. The following are the scientific names of such as I can call to mind:

- “Quercos Phellos, L. [Willow Oadk]

- “Q——imbricaria, Mx. [Shingle Oak]

- “Q——heterophylla, Ms. f [Bartram’s Oak]

- “(and perhaps some others)

- “Several species of Pinus, Abies, and Larix. [pine, fir, larch]

- “Magnolia acuminate, L. [Cucumber Tree Magnolia]

- “M——Umbrella, Lam. [tripetala]

- “M——Fraseri, Walt. [Fraser Magnolia]

- “M——cordata, Mx. (I think). [Yellow Cucumber Tree]

- “Gymnocladus Canadensis, Lam. [Kentucky Coffee Tree]

- “Aesculus flava, Ait. [Yellow Buckeye or Horsechestnut]

- “Ae——Pavia, L. [Red Buckeye]

- “Cercis Canadensis, L. [Eastern Redbud]

- “Gleditschia triacanthos, L. [common Honeylocust]

- “Halesia tetraptera [Carolina Silverbell]

- “Stuartia Virginica, Ca. DC.

- “Carya olivoformis, Nutt. [Hickory]

- “Philadelphia grandiflora, Wild. [Big Scentless Mockorange]

- “Staphylea trifolia, L. [American Bladdernut]

- “Tilia Americana, L. [American Linden]

- “Zanthoxylum Americanum, Mill. [Common Pricklyash]

- “Taxus Canadensis, L. [Canada Yew]

- “Styrax Grandifolium [Bigleaf Snowball]

- “Liquidamber styraciflua, L. [American Sweetgum]

- “and a number of others which I cannot now recollect—beside a large number of herbaceous plants & undershrubs.”

- Anonymous [“B.—A Massachusetts Subscriber”], December 1850, “Trees and Pleasure Grounds of Pennsylvania” (Horticulturist 6: 69–71)[22]

- “The grounds which I described in a former number of the Horticulturist, were not only planted by the hand of taste, but had been kept with care; to the one of which I shall now speak, time had added new beauty in its stately trees, but his destroying finger was visible in all else. As we approached the former residence of HUMPHREY [sic] MARSHALL, (near the village of Marshallton,) the massive foliage of a variety of trees rising above a dilapidated fence, gave us a foretaste of what awaited us. We were directed to an old gate as the nearest entrance, but found, when it was with difficulty opened, that a huge Tecoma, or trumpet creeper, and Aristolochias twining their cordage like branches from tree to tree, barred the passage—the gentlemen of the party effected an entrance for us through the luxuriant vines, and we stood in what was once the pride and delight of one of the earliest arboriculturists. MARSHALL was first cousin to JOHN BARTRAM, and from him he probably derived much of his knowledge of plants, for in 1773 he followed his cousin’s example, and commenced this botanic garden, where he gathered together the most interesting trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants of our country, with many curious exotics.

- “In 1785, he published an account of our native trees and shrubs, entitled Arbustum Americanum, the first work of the kind printed in this country. It received little attention here, as it was half a century in advance of the age—it was, however, quickly appreciated abroad, and translated into most of the languages of modern Europe. He was in correspondence with many eminent men, and sent large quantities of American seeds and plants to England. When the infirmities of age and a cataract had rendered him nearly blind, he could still recognise his favorite trees and walks, and delighted to welcome his friends in the garden he had planted.

- “Many of the trees have now, at the end of 77 years, attained a large size; the sovereign of the place is a Magnolia accuminata, which lifts up its ‘leafy crown’ to the height of one hundred feet, in form perfectly symmetrical, giving out branches from its stout trunk at regular intervals; it must be a glorious sight to see it in the spring, covered with its large, white [pale buff, Ed.] blossoms. Near by flourishes the Gymnocladus canadensis, or Kentucky coffee, whose broad green pods and divided leaves have a grotesque and foreign appearance. This tree would probably thrive well in New-England, as it grows in Canada. There were also fine specimens of the Carya olivaeformis, or peecan [sic] tree, the Illinois hickory as it is sometimes called; this tree fruits sparingly in the climate of Pennsylvania, yet it grows well, and is an ornamental tree.

- “I noticed nearly the same variety of oaks as in BARTRAM’S garden, especially one of the Quercus heterophylla of a remarkably fine shape. This variety of oak I have never seen growing in Massachusetts, but it is worthy of a place in every pleasure ground, as its foliage has all the beauty of the willow, while the tree has the distinguishing characteristics of the oak. A few herbaceous plants still send up some pale flowers from amid the rank grass, which has overgrown both borders and walks. Some of the hardy and vigorous sorts have eradicated the native claimant of the soil, and grow luxuriantly,—as the Vinca or Periwinkle, whose brilliant dark leaves formed a bed many yards square.

- “After examining the trees for some time, the grand nephew of HUMPHREY MARSHALL, who inherited the place, invited us into the house built by the botanist, where we were shown the telescope sent him by D. FOTHERGILL, of London, whose name is engraved upon it; he pointed out also, the place in the closet where MARSHALL concealed it by a false back, during the time that the British army were in the neighborhood, for MARSHALL added to his love of the flowers of earth, a taste for studying the stars. . . . We noticed the little observatory which he built in one corner of the house, where it was his delight to watch the motions of the heavenly bodies. It was with regret that I looked again upon the tangled wilderness, ‘where once a garden smiled, and now where many a garden flower grows wild,’ and walked towards the burial place of Bradford meeting, in which the remains of MARSHALL were interred nearly fifty years ago. We crossed a stile shaded by magnificent oaks, which must have been spared from the primeval forests. They formed a pretty group near the old fashioned meeting-house, their gnarled and picturesque appearance presenting a strong contrast to the usually plain and exposed state of the Friends’ houses of worship. The grave-yard was a wide field, unvaried by shrub or stone, the undulating hillocks only marking the ‘furrows where human harvests grow.’ This neglect of the Friends to ornament the last resting places of their kindred, appears strange to one of a different faith, since there seems to be an innate desire in the breast of every human being, that some memorial should recall his name to survivors. Trees and shrubs at least, might relieve the monotony of these cheerless fields, for in such monuments there can be no ostentation; the poorest laborer can plant a seed, or set a tree. We were shown as nearly as possible, the place where Marshall’s grave is supposed to be, but tradition rarely speaks with certainty at the end of half a century. I sought for some memento of the spot to take to my distant home; the only blossom I could find in the rank grass, was a pale white Spiranthes, which I carried away from this desolate habitation of the dead.

- “It is pleasant to trace out how much the taste of one person influences and improves that of a whole neighborhood. JOHN BARTRAM, by his love of collecting and planting rare and curious trees, inspirited his cousin to follow in his footsteps. MARSHALL embellished his paternal farm in Marlborough, the township where PIERCE’S [sic] Arboretum now flourishes. And The Woodlands, a visit to which I shall next describe, are in close proximity to BARTRAM’S garden, whose owner was a constant friend and assistant of HAMILTON.”

Images

Map

Other Resources

Humphry Marshall House, Historic American Buildings Survey/Engineering Record/Landscape Survey

Historic and Notable Landmarks of the U.S.

Notes

- ↑ Robert R. Gutowski, “Humphry Marshall’s Botanic Garden: Living Collections 1773–1813" (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1988), 13, view on Zotero.

- ↑ See Fothergill to Marshall, March 2, 1767, William Darlington, Memorials of John Bartram and Humphry Marshall: With Notices of Their Botanical Contemporaries (Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1849), 495, 497, 502, 513, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For the argument that Marshall’s garden dates from 1773, see Gutowski 1988, 13, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For a partial catalog of 136 plants that have survived and/or were part of the original plantings at Marshall’s botanic garden, see Gutowski 1988, Chapter 2 esp., view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gutowski 1988, 7, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Marshall, Arbustum Americanum: The American Grove, Or, An Alphabetical Catalogue of Forest Trees and Shrubs (Philadelphia: Joseph Crukshank, 1785), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Marshall 1785, 4, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For the taxonomic history of Acer saccharum Marsh., see Frank Santamour, Jr. and Alice Jacot McArdle, “Checklist of Cultivated Maples II. Acer Saccharum Marshall,” Journal of Arboriculture 8 (June 1982): 164–67, view on Zotero; M. L. Fernald, “Botanical Specialties of the Seward Forest And Adjacent Areas of Southeastern Virginia,” Contributions from the Gray Herbarium of Harvard University 156 (1945), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gutowski 1888, 4, view on Zotero; see also Louise Conway Belden, “Humphry Marshall’s Trade in Plants of the New World for Gardens and Forests of the Old World,” Winterthur Portfolio 2 (1965): 112, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gutowski 1988, 1–5, view on Zotero; Belden 1965, 109, view on Zotero; Darlington 1849, 487, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gutowski 1988, 8, view on Zotero. See also William M. Schneider and Martha A. Potvin, “The Historic Bartram’s (Carr’s) Garden Collection in West Chester University’s William Darlington Herbarium (DWC),” Bartonia 64 (2009): 45–54, view on Zotero; Robert B. Gordon, “The ‘Darlington Herbarium’ at West Chester,” Bartonia 22 (1942): 6–9, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Darlington 1849, 487, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Franklin, The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, ed. William B. Willcox, 47 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976), 20:71, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gutowski 1988, 7–8, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Darlington 1849, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Pursh, Flora Americae Septentrionalis; Or, a Systematic Arrangement and Description of the Plants of North America, 2 vols. (London: White, Cochrane & Co., 1814), view on Zotero.

- ↑ “Chester County Cabinet of Natural Science,” Register of Pennsylvania 1 (May 10, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gutowski 1988, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, A Life of Travels in North America and South Europe, or Outlines of the Life, Travels and Researches of C. S. Rafinesque (Philadelphia: F. Turner, 1836), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Darlington, Flora Cestrica: An Attempt to Enumerate and Describe the Flowering and Filicoid Plants of Chester County in the State of Pennsylvania. With Brief Notices of Their Properties, and Uses, in Medicine, Domestic and Rural Economy, and the Arts (West-Chester, PA: The author, 1837), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Darlington to John Bohlen, September 10, 1849, Chester County Historical Society, quoted in Belden, 1965, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous [“B.—A Massachusetts Subscriber”], “Trees and Pleasure Grounds of Pennsylvania,” Horticulturist, And Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 6 (February 1851): 69–71, view on Zotero.