Copse

(Coppice)

See also: Grove, Thicket, Wilderness, Wood

History

A copse (or coppice)—a grouping of trees and shrubs—was akin to a clump or thicket in the choice and the arrangement of vegetation. A copse, however, was sometimes distinguished from these other features by virtue of its association with husbandry. Copses were thinned regularly by removing branches and limbs, which were then used for purposes other than ornamentation by the landowner. According to Walter Nicol (1812), this practice of trimming trees and shrubs also distinguished a copse from a wood, since the former included trees and shrubs that were never permitted to grow to “any considerable size.” The latter, by contrast, contained towering trees (see also Charles Marshall [1799] and Humphry Repton [1803]). Nicol drew further distinctions between natural (or self-sown) copses and deliberately planted artificial ones. Lexicographers, including Ephraim Chambers (1741–43), Samuel Johnson (1755), and Noah Webster (1828), focused only on the material uses of wood and did not acknowledge the use of copses in gardens. Garden treatise writers, however, from the Englishman John Worlidge (1669) to American A. J. Downing (1849) discussed the design of copses in terms of their layout with walks to create pleasant spaces for walking.

Seeking evidence of copses in the American context poses several problems. Descriptions and images rarely identify a copse as either natural or artificial. In addition, not every instance of copse cited in this study makes clear that trees and shrubs were “coppiced,” a term that suggested a wood feature that had been (or looked like it had been) cut back periodically. It should also be noted that the identification of copses is further impeded by the fact that the feature has multiple associations with husbandry, natural scenery, and landscape design. Unless the term is directly inscribed on an image, it is difficult to recognize the form.

In the references gathered here a link is implied between copses and the natural landscape, even though it is unclear whether natural or artificial copses are described. Rev. Manasseh Cutler in 1803, when describing The Woodlands, near Philadelphia, used the term to describe an arrangement of native trees as opposed to William Hamilton's collection of foreign trees, which he called an “artificial grove.” This distinction suggests that the term “copse” was used to describe a group of native trees.

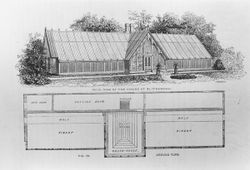

Because a copse was, as Noah Webster specified, a small wood “consisting of under.wood or brushwood,” it was particularly well suited to provide a dense screen of vegetation. Although most designers recommended using shrubberies or thickets as screening devices, a few 19th-century treatise writers suggested copses. Thomas Green Fessenden in 1823 suggested planting copses in graveyards because they could both conceal graves and provide a contrast to the stark stones. At Blithewood on the Hudson River, the vinery was backed by a copse that hid both the working side of the building and provided a pleasing backdrop [Fig. 1]. James E. Teschemacher, in an essay that detailed how to create the illusion of greater space in small gardens, recommended planting copses at the outer boundary of gardens abutted by woods in order to make the neighboring woods appear as if they were part of the designed landscape. In this case, the copse would provide a graceful transition from lawn to wood.

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Strachey, William, 1612, describing Kecoughtan, VA (Wright and Freund, eds., 1967: 67)[1]

- “. . . an admirable portion of Land comparatively high, wholsome and fruictfull, the Seat sometymes of a thowsand Indians. . . so much grownd is there Cleered and open, ynough with little Labour alreddy prepared. . . and where besyde we fynd many fruict-trees, a kynd of Goose-berry, Cherries, and other Plombes, the Mariock-apple, and many pretty Copsies, or Boskes, as yt were, of Mulberry trees.”

- Morse, Jedidiah, 1789, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1789: 381)[2]

- “. . . the lands in that side are laid out somewhat in the form of English gardens, in meadows and grass grounds, ornamented with little copses, circular clumps and single trees.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, November 22, 1803, in a letter to his daughter, Mrs. Torrey, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (1987: 2:145)[3]

- “We then walked over the pleasure grounds in front and a little back of the house. It is formed into walks, in every direction, with borders of flowering shrubs and trees. Between are lawns of green grass, frequently mowed to make them convenient for walking, and at different distances numerous copse of native trees, interspersed with artificial groves, which are set with trees collected from all parts of the world.” [Fig. 2]

- Fessenden, Thomas Green, January 25, 1823, “National Burying Ground” (New England Farmer 1: 206)[4]

- “This grave-yard contains an area of two or three acres, enclosed by a plain wooden fence, and sprinkled with copses of native cedar, stinted in their growth and many of them withered, either from the poverty of the soil, or from having their roots broken by the spade of the grave-digger. There are however, enough living to conceal many of the graves; and their verdure, contrasted with the grey tomb stones produces an agreeable effect.”

- Dearborn, H. A. S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Harris 1832: 84)[5]

- “The general appearance of the whole grounds, should be that of a well-managed park, and the lots only so far ornamented with shrubs and flowers, as to constitute rich borders to the avenues and pathways, without giving to them the aspect of a dense and wild coppice, or a neglected garden, whose trees and plants have so multiplied and interlaced their roots and branches, as to completely destroy all that airiness, grace, and luxuriance of growth, which good taste demands.”

- Teschemacher, James E., November 1, 1835, “On Horticultural Architecture” (Horticultural Register 1: 409, 411)[6]

- “Suppose the area or garden space to be small, one great object would be to shut out by shrubbery the boundaries, so that the small extent might not appear, to fill every angle and corner with the Lilac or other large and spreading plant, and to take every advantage of the adjoining land. Thus imagine the neighboring piece to be grass; by means of a very open or of a sunk fence and a grass plat the grass on both lands would appear to combine and present an extensive expanse of green, or if wood adjoins, then by judicious transplantation an uninterrupted line of copse would be formed, on which the eye would rest with pleasure. The invisible fences commonly used in England, might here be of great service, they are made of thick iron wire, about four feet high, with thin iron posts at distances of eight or ten feet, painted black, so that they form no impediment to such combinations of prospect with contiguous properties. The same may be done where a rivulet or a piece of water exists near, observing always that such innocent appropriations of our neighbor’s property is much better enjoyed when only caught at glimpses and between intervals of shrubbery. . .

- “The vicinity of Boston abounds so much in every variety of beautiful landscape, that there is scarcely any place where art is less required in laying out pleasure grounds; walks now winding through the small adjacent copse filled with wild flowers assembled from every location where they are found, gradually ascending an elevated spot where the beauty of the prospect bursts on the astonished eye, then leading into the cultivated flower garden.”

- Adams, Nehemiah, 1838, describing Boston Common, Boston, MA (Adams 1838: 40)[7]

- “Had its principles been regarded, we should have seen trees of various foliage, here standing alone, and there intermingled in copses and groves—arranged, indeed, so as to imitate nature herself, in her picturesqueness as well as her beauty.”

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo, 1847, excerpt from “Walden” (quoted in Clarke 1993: 2:47)[8]

- “There [in my garden] broad-armed oaks, the

- copses’ maze,

- The cold sea-wind detain;

- Here sultry Summer over-stays

- When Autumn chills the plain.”

- “There [in my garden] broad-armed oaks, the

- Miller, Lewis, June 5, 1849, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (c. 1850: 108)[9]

- “The mansion house itself appears venerable and convenient[.] A lofty portico ninety-six feet in length, Supported by Eight Pillars, has a pleasing effect when viewed from the water: ornamented with little copses—clumps and Single trees—. add a romantick and picturesque appearance to the whole Scenery.” [Fig. 3]

Citations

- Worlidge, John, 1669, Systema Agriculturae (1669: 92)[10]

- “Coppices may also be planted about Autumn with the young Sets or Plants, the best way is in rows about ten or fifteen foot distance, for then may you reap the benefit of the Intervals, by Ploughing, or Digging, and Sowing, till the Trees are well advanced; Carts also may the better pass between at the time of felling without injury to the stems, or danger of the Cattel; There will also be many pleasant Walks, and yet an equal burthen of Wood at the full growth of the Coppice, as though they were thick, and confusedly planted.”

- Langley, Batty, 1728, New Principles of Gardening (1728; repr., 1982: 195–201)[11]

- “General DIRECTIONS, &c. . .

- “XXVIII. Distant Hills in Parks, &c. are beautiful Objects, when planted with little Woods; as also are Valleys, when intermix’d with Water, and large Plains; and a rude Coppice in the Middle of a fine Meadow, is a delightful Object.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, Cyclopaedia (1741: 1:n.p.)[12]

- “COPPICE or COPSE, a little wood, consisting of underwoods; and may be raised either by sowing, or planting. See WOOD.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 1:n.p.)[13]

- “COPPICE. n.s. [coupeaux, Fr. from couper, to cut or lop. It is often written copse.] Low woods cut at stated times for fuel; a place over-run with brushwood.”

- Hale, Thomas, 1758–59, A Compleat Body of Husbandry (1:276, 288–89)[14]

- “There is great advantage in planting the young trees in rows distant from one another, the husbandman may make use of the ground between for any other growth, till the trees are of some height; and this tilling between, far from hurting the young trees, will assist their growth: and the coppice will grow afterwards with a beautiful regularity, being all laid out into natural walks and alleys. . .

- “There is a great deal of difference between the plantation of the coppice wood shrubs or the pol-lards, and that of forest trees. The former are intended for immediate growth and immediate use; but these are to stand a long time, and on their strength and soundness, at the end of so many years, depends their value. . .

- “The richest the deepest soils produce the largest and the fairest trees.”

- Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce, 1769, The Complete Farmer (1769: n.p.)[15]

- “COPPICE, low woods, cut at stated times for poles, fuel, &c.

- “If you are to plant a coppice, says the ingenious Mr. Lisle, it is a good way to set your plants in trenches, as one raises quickset hedges, and not to sow seeds, for they are tedious in coming forward, and will tire one’s patience in weeding them. I would not set above four plants in twelve feet square, and at regular distances, so that the benefit of ploughing might not be lost; and then at six or seven year’s growth I would plash, by laying the whole shoot, end and all, under the earth in the trenches, which would not therefore be choaked, but shoot forth innumerable issues: this, by great experience, oak, ash, hazle, and withy, will do.”

- Deane, Samuel, 1790, New-England Farmer (1790: 62)[16]

- “COPSE, or COPPICE, a piece of underwood. ‘When a copse is intended to be raised from mast or seed, the ground is ploughed in the same manner as for corn; and either in autumn or in spring, good store of such masts, nuts, seeds, berries, &c. are to be sown with the grass, which crop is to be cut, and then the land laid for wood. They may be also planted about autumn with young sets, or plants, in rows about ten or fifteen feet distance. If the copses happen to grow thin, the best way of thickening them is, to lay some of the branches or layers of the trees, that lie nearest to the bare places, on the ground, or a little in the ground. These detained with hooks, and covered with fresh mould, at a competent depth, will produce a world of suckers, and thicken a copse speedily.’ Dict. of Arts.”

- Marshall, Charles, 1799, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening (1799: 1:119)[17]

- “As to small plantations, of thickets, coppices, clumps, and rows of trees, they are to be set close according to their nature, and the particular view the planter has, who will take care to consider the usual size they attain, and their mode of growth. An advantage at home for shade or shelter, and a more distant object of sight, will make a difference: for some immediate advantage, very close planting may take place, but good trees cannot be thus expected; yet if thinned in time, a strait tall stem is often thus procured, which afterwards is of great advantage.”

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803: 61–62)[18]

- “The beech woods in Buckinghamshire derive more beauty from the unequal and varied surface of the ground on which they are planted, than from the surface of the woods themselves; because they have generally more the appearance of copses, than of woods: and as few of the trees are suffered to arrive to great size, there is a deficiency of that venerable dignity which a grove always ought to possess.”

- Nicol, Walter, 1812, The Planter’s Kalendar (1812: 47–48)[19]

- “A natural copse, with respect to its origin, and the kinds of plants, (excepting resinous trees), differs in nothing from a wood, as above defined. A copse is never allowed to rise to timber of any considerable size; but is always cut down for fuel, stakes, poles, the bark, &c. When the timber-growing kinds are allowed to remain untouched, and are trained up to trees, it is then changed into a wood. The situation of a natural copse, of course, is generally such as that of a wood,—of which, in truth, it is the prototype, and would, if left to nature, soon become one; but it is kept in a state of copse by man, often from his necessities, and sometimes from his choice.

- “Copses are often planted, or, more properly, sown, with the intention of keeping them merely as such, and to answer various useful purposes; as the production of stakes, rails, poles, hoops, charcoal, fuel, or bark. They are also frequently reared in parks and grounds as objects of ornament, or as covers for game. Hence, artificial copses are frequently to be found in very favourable situations and soils; and in such their products are exceeding profitable.

- “The extent of a copse, like a wood, may be any thing from half an acre and upwards; but there is no species of plantation so well adapted to fill up, or occupy small corners, or broken spots in arable fields, occasioned by the operations of mining or quarrying, or to cover the broken rugged banks of a stream or river. In parks, they appear to great advantage, when judiciously placed, and contrasted with woods and groves.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: n.p.)[20]

- “COP’PICE, COPSE, n. [Norm. coupiz, from couper, to cut, Gr. . .]

- “A wood of small growth, or consisting of underwood or brushwood; a wood cut at certain times for fuel.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849; repr., 1991: 93)[21]

- “[The homeowner’s] walks would lead through varied scenes, sometimes bordered with groups of rocks overrun with flowering creepers and vines; sometimes with thickets or little copses of shrubs and flowering plants.”

Images

Inscribed

Lewis Miller, “Mount Vernon” [detail], in Orbis Pictus (c. 1849), 108.

Associated

William Strickland, “The Woodlands,” 1809, in Casket 5, no. 10 (October 1830): pl. opp. 432.

Anonymous, “View of the Vinery at Blithewood,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 1, no. 2 (August 1846): pl. opp. 58.

Attributed

Notes

- ↑ Louis B. Wright and Virginia Freund, eds., The Historie of Travell into Virginia Britania (1612) (Nendeln and Liechtenstein: Kraus, 1967), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jedidiah Morse, The American Geography; Or, A View of the Present Situation of the United States of America (Elizabeth Town, NJ: Shepard Kollock, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Parker Cutler, Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D. (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Green Fessenden, “National Burying Ground,” New England Farmer 1, no. 26 (January 25, 1823): 206, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thaddeus William Harris, A Discourse Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on the Celebration of Its Fourth Anniversary, October 3, 1832 (Cambridge, MA: E. W. Metcalf, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James E. Teschemacher, “On Horticultural Architecture,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 1 (November 1, 1835): 409–12, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Adams, Boston Common (Boston: William D. Ticknor and H. B. Williams, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Graham Clarke, ed., The American Landscape: Literary Sources and Documents, 3 vols. (East Sussex, England: Helm Information, 1993), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lewis Miller, Orbis Pictus: A Picturesque Album to the Ladies of York, Pennsylvania (Williamsburg, VA: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Worlidge, Systema Agriculturae, The Mystery of Husbandry Discovered (London: T. Johnson, 1669), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Batty Langley, New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c. (1728; repr., New York: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . ., 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Hale, A Compleat Body of Husbandry Containing Rules for Performing, in the Most Profitable Manner, the Whole Business of the Farmer and Country Gentleman, 2nd ed., 4 vols. (London: T. Osborne, 1758), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce, The Complete Farmer, or A General Dictionary of Husbandry, 2nd ed. (London: R. Baldwin et al., 1769), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Deane, New-England Farmer, or Georgical Dictionary (Worcester, MA: Isaiah Thomas, 1790), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Marshall, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening, 1st American ed., 2 vols. (Boston: Samuel Etheridge, 1799), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter Nicol, The Planter’s Kalendar (Edinburgh: D. Willison for A. Constable, 1812), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.