Labyrinth

See also: Walk, Wilderness

Definition

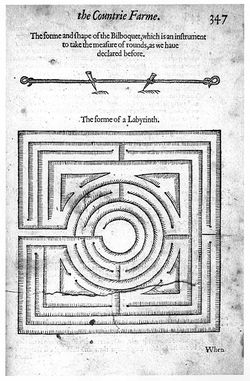

Although labyrinth was the term of choice for professional writers such as Thomas Sheridan (1789), who described it as “a place formed with inextricable windings,” the term was virtually synonymous with that of “maze” in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century gardening literature, as well as in general usage.[1] Samuel Johnson, for example, in 1755 defined labyrinth as “a maze.” The winding walks referred to by Johnson and other garden writers (such as Philip Miller and Bernard M’Mahon) were the distinguishing feature of labyrinths. This characteristic was also clear in illustrations from English garden treatises that were available in North America [Figs. 1–3]. These sharply turning walkways were frequently framed by dense, high hedges, and often backed by shrubs and woods that occluded the perambulator’s view (see Walk). A visitor’s perception was affected by the combination of dense vegetation and intricately patterned walks, which produced an intentional state of disorientation and surprise. If the visitor succeeded in penetrating to the center of the labyrinth, he or she was typically rewarded by arriving at an ornamented space, often highlighted with a garden structure, such as an obelisk, a temple, or a seat. Thomas Jefferson (1804) suggested such a design in his reference to a thicket labyrinth.

Gardeners and garden writers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries mentioned a broad range of vegetation that could be used to construct this garden feature. Hannah Callender (1762) referred to cedar and spruce that were maintained as a hedge; George Washington mentioned pine; Jefferson specified broom; and John Pendleton Kennedy reminisced about boxwood. M’Mahon recommended hedges of hornbeam (a nut-bearing tree), beech, elm, “or any other kind that can be kept neat by clipping,” or, in the case of smaller labyrinths, box edged with plants. All of these materials could produce the desired density and could also, because of either thickness or prickly texture, prevent visitors from wandering off the carefully laid out paths. Because these plants also tolerated trimming well, the edges of walks could be cleanly demarcated. At times, nonliving material was substituted for living hedges and borders. At New Harmony, for example, four-foot-high wooden fences covered with various climbing vines were used to define the walks.

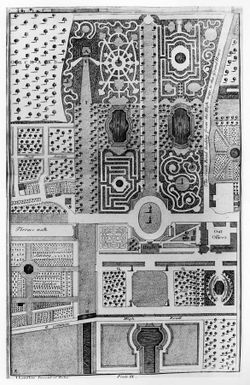

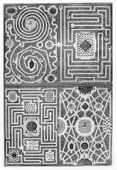

Many of the plants utilized in labyrinths were also employed in wildernesses, as was the technique of planting low hedges or borders backed by trees and shrubs (see Wilderness). Hence, many garden writers conflated labyrinth and wilderness, as in the case of John Parkinson (1629). The labyrinth at times was referred to as a specialized form of wilderness, for example M’Mahon(1806). Although Batty Langley, in New Principles of Gardening (1728), referred to wildernesses and labyrinths as separate features, he treated them similarly, placing them in remote regions of gardens and even balancing one against another, as in the plan for an improved garden at Twickenham. His description of this garden specified the location of the labyrinth, among the grove and wilderness, seen above the statue in the plan [Fig. 4]. He described the “Improvement of the Labyrinth at Versailles” [Fig. 5] as “the finest design of any” that he had ever seen.

While the meaning of the term “labyrinth” was relatively clear throughout the period of this study, the history of its presence in American gardens is less well understood. According to Philip Miller (1759), labyrinths were a rarity in English gardens and successful only in large-scale gardens, such as those at Hampton Court. Given these conditions, one might expect few labyrinths in the American context, especially since the funds and royal imperative associated with Hampton Court were largely absent in the New World.[2]

Nevertheless, a number of labyrinths in public and private American grounds have been documented. Labyrinths were sources of amusement and therefore were included in the popular public gardens, such as Gray’s Tavern in Philadelphia, and Berkeley Springs in Virginia (later West Virginia) [Fig. 6]. In 1762 Hannah Callender described a labyrinth at Judge William Peters’s Belmont Mansion, near Philadelphia. In this garden, the labyrinth was part of a larger arrangement of features, including parterres, topiary, and clipped hedges, which were associated with the geometric or ancient style as opposed to modern fashion (see Ancient style, Geometric style, and Modern style).[3] Labyrinths were built at Mount Vernon and Monticello. Jefferson made a labyrinth in the thicket, a garden feature closely related to shrubbery and often associated with the modern or natural style of landscape gardening (see Modern style and Thicket).

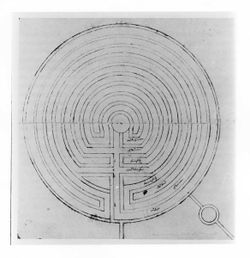

Most descriptions of labyrinths in the American context unfortunately do not specify labyrinth design, which could take on a variety of configurations. The condemnation of “stars and other ridiculous figures” issued by the Encyclopaedia (1798) suggests some range of taste or preference in the areas of design. Jefferson’s plan of Monticello is exceptional because it documents a spiral, pinwheel-like arrangement of shrubs, with six-foot-wide walks evenly dispersed. The plan of the labyrinth at Harmony, Pa., is an elaborate version of a spiral configuration [Fig. 7] and was repeated at the settlement in New Harmony, Ind., which was modeled after the Pennsylvania community.

The evidence of labyrinths in early American gardens suggests that the number of labyrinths declined as the feature was increasingly associated with old-fashioned garden practices. In his dictionary (1828), Noah Webster stated that the garden oriented definition of labyrinth was no longer used. A. J. Downing, in his 1849 edition of A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, firmly categorized labyrinths under the rubric of the geometric (or ancient) garden style of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Yet, labyrinths never completely disappeared from the American landscape, as demonstrated by a view from the Mount Croton Garden in New York [Fig. 8], and its elaborate hedged labyrinth, exactly in the rectangular form that Downing declared was used by ancient gardeners. The popularity of this labyrinth for public amusement assured its continuity.

-- Anne L. Helmreich

Images

Inscribed

John Haviland, The Pagoda and Labyrinth Garden, Fairmount Waterworks, c. 1828. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pa.

Batty Langley, "Four several Designs for Wildernesses and Labyrinths", 1728.

Associated

Attributed

W. Weingartner, Town Plan of Harmonie, Indiana, 1833. Pennsylvania State Archives.

W. Weingartner, Town Plan of Harmonie, Indiana, 1833. Pennsylvania State Archives, detail.

Texts

Notes

- ↑ For a general discussion of labyrinths in gardens, with illustrated examples, see Adrian Fisher and George Gester, Labyrinth, Solving the Riddle of Maze (New York: Harmony Books, 1990).

- ↑ It should be noted that the maze currently located in the grounds of the Governor’s Palace, Williamsburg, Va., is a twentieth-century construction for which no documentation during the colonial period of habitation exists. See Charles B. Hosmer, “The Colonial Revival in the Public Eye: Williamsburg and Early Garden Restoration,” in The Colonial Revival in America, ed. Alan Axelrod (New York: W. W. Norton, 1985) for a discussion of the Williamsburg gardens and their role in defining colonial revival garden styles.

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “Landscape Gardening in the Early National Period,” in Views and Visions, American Landscape before 1830, ed. Edward J. Nygren with Bruce Robertson(Washington, D.C.: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1986), 144.