Fence

See also: Espalier, Gate, Ha-Ha, Hedge, Wall

Discussion

Humphry Repton wrote in 1803 in reference to England that “every county has its peculiar mode of fencing, both in the construction of hedges and ditches, which belong rather to the farmer than the landscape gardener.”[1] In America, where the tasks of partitioning, cultivating, and embellishing the landscape were considered inseparable, the distinction between farmer and gardener was less easily made. Frequent references to the fence in both the written and visual record place it among the most fundamental elements of the designed landscape in America. A fence, as dictionary definitions agree, enclosed areas such as gardens, cornfields, parks, woods, or groups of trees. As G. Gregory (1816) noted, the feature could be formed by a hedge, wall, ditch, or bank. Terms for different fence types abound in American landscape design vocabulary: blind, board, close, cradle, cross, double, foss, hurdle, invisible, live, open board, pale/paling, palisade, picket, post-and-plank, post-and-rail, snake, sunk, trellis, Virginia, wattle, wire, worm, and zigzag.[2]

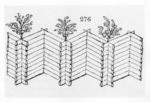

The choice of fence type was dictated by the materials available, local custom, and the need at hand. For instance, worm fences (also called zigzag, snake, split rail, or Virginia fences) did not require posts or post holes and therefore were easily moved to accommodate changing field use and avoided the problem of posts rotting in soil. They were also useful in areas where rocky soil made it difficult to dig post holes or in wooded areas where trees made straight fence lines impractical, as seen in the watercolor sketch by John Lewis Krimmel [Fig. 1]. Paled fences offered a more solid line of defense against deer and rabbits, but had less flexibility and required more labor and finished lumber [Fig. 2]. Such high fences were effective barriers for animals as well as humans, as attested by Robert Waln, Jr.’s 1825 description of the board fence at the Friends Asylum for the Insane in Pennsylvania.

Paling fences created visual barriers and were sometimes erected to screen unpleasant views or to provide privacy, particularly in urban settings [Fig. 3]. For instance, in 1857 John Fanning Watson complained that “in the usual selfish style of Philadelphia improved grounds” at William Bingham’s Philadelphia residence, “the whole was surrounded and hid from the public gaze by a high fence.” Fences were also used to direct the gaze, whether toward a house, as in Francis Guy’s chairback painting of Rose Hill in Baltimore [Fig. 4], or other focal point. In other cases, fences such as sunken types (later replaced by wire fences) were desired for their inconspicuous presence in the landscape. Numerous descriptions and horticultural advice columns praised the effect of unobstructed views created by enclosures that kept animals or human traffic at bay with minimal visibility (see Ha-Ha).

Fences were constructed from a variety of materials. In the Tidewater’s sedimentary soils where stone was scarce, wood was the most common material and was used mainly in paled, post-and-rail or board, and worm fences. Although types of wood that could be used were varied, a typical paling fence utilized different types of wood. For example, hard wood, such as locust, cedar, or oak, was often used for posts; wood with tensile strength, such as oak, poplar, or pine, was used for rails; and lightweight wood, such as pine, could be employed for the pales.[3] Although worm fences [Fig. 5] have been documented in Delaware, New York, and as far north as Canada, they were so common in the Tidewater area that they were often identified as Virginia fences. Thomas Anburey even reported that New Englanders described a drunken man’s impaired movements as “making Virginia fences.” In southern New England’s glacier-formed topography, abundant fieldstone was used for stone walls, which sometimes were referred to as stone fences.[4] Fences could also be created from live plants, predominantly thorn (hawthorn and buckthorn), although writers including Edward James Hooper (1842) and Charles Wyllys Elliott (1848) recommended osage orange, cedar, Chinese arbor vitae, privet, holly, honey and black locust, beech, willow, and hemlock. The advantages of live fences were a matter of great debate, particularly in early nineteenth-century publications that advocated the “new agriculture.” These writings included those by the New York and Massachusetts Agricultural Societies, and later, in periodical form, the Horticulturist. In addition to their durability and long-term cost savings, it was argued that live fences harmonized better with the surrounding landscape (see Hedge). A similar effect could also be achieved with other fences, as suggested by Edward Sayers (1838), by training “vines and creepers” to conceal old and unsightly fences.

Iron gates were used in the eighteenth century at such sites as Westover, on the James River, Va., and the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg, and iron fences were employed for the fronts of elite dwellings and notable institutions.[5] It was not, however, until the second quarter of the nineteenth century when the expansion of America’s domestic iron industry and advances in cast iron made iron fences affordable for those of more modest means. This availability is reflected in the more than one hundred fence patents that were registered between 1801 and 1857.[6] Treatises, such as those by A. J. Downing (1849) and William H. Ranlett (1851), provided examples of fashionable designs to be installed in front of suburban yards. Elaborate iron-work fences were particularly popular as enclosures for urban parks [Fig. 6], educational institutions [Fig. 7], and family burial plots [Fig. 8]. These plots, with their elaborate fences, were favorite subjects in illustrated books of the new rural cemeteries [Fig. 9].

Despite the variety of materials and designs, fences shared many common functions. Garden fences, like walls, created micro-climates for plants: southern façades were ideal for promoting early harvests of fruit trees trained on espaliers or protecting tender nursery plants, while northern sides provided sheltered, shady spots in long dry summers. William Cobbett (1819) emphasized the value of fences as shelters in America, given its extremes of heat and cold in contrast to the more temperate English climate.

Fences were the primary boundary markers that defined property lines and distinguished “improved” from “unimproved” land, and early legislation frequently required the fencing of landholdings. Fences also marked divisions within a property owner’s estate, such as those between field, meadow, pasture, orchard, and yard; and, within the garden itself, fences separated areas such as the flower garden, kitchen garden, and nursery [Fig. 10]. The form of the fence often reflected its position or function. For example, post-and-rail fences would mark the boundaries and the divisions of the fields, while a palisaded brick wall served as a retaining wall along a slope, and a picket fence delineated the geometrically regular garden adjacent to the house [Fig. 11]. Not surprisingly, the public view of the property was often framed by more ornamented fence types, and aspiring owners could draw from pattern books, such as that by William and John Halfpenny (1755), for inspiration [Fig. 12]. Numerous images, including Caroline Betts’s painting of Lorenzo on Lake Cazenovia [Fig. 13], show a more elaborate treatment given to the fences in front of houses in contrast to the pale or post-and-rail fences that lined roads and enclosed meadows. William Cobbett (1819), in this vein, described a hierarchy of fences from the “rudest barriers” to the “grandest” and “noblest,” along with “every degree of gradation” in between, and Asher Benjamin (1830) recommended that the size of front fences be suited to the scale of the house.

Distinctions in the fence in the landscape were also made by painting sections or the sides of fences. In several New England examples, including the Dennie overmantle [Fig. 14], utilitarian fences were painted red, while more formal fence sections near the house were painted white. In still other instances, such as the painting View Along the East Battery [Fig. 15], parts of the fence furthest from the house were left unpainted in contrast to the painted fence in front of the house. Views, such as Marie L. Pilsbury’s Louisiana plantation scene [Fig. 16], are especially striking since the white gate of the drive stands out in sharp contrast to the unpainted brown post-and-rail fence. While the selective use of white served to highlight portions of the fence, it also conserved white paint, which was more costly.[7]

Fences were critical for keeping livestock in and garden pests contained. During the early years of settlement when livestock (such as pigs) were not restrained, colonists fenced their garden plots, while animals wreaked havoc on the open fields of Native Americans.[8] In large estates, above-ground fences or sunken fences around the house were used to separate animals grazing in the open land of larger, more naturalistic landscape parks from more densely planted areas immediately surrounding the house, as depicted in Francis Guy’s 1805 painting of Perry Hall in Baltimore [Fig. 17]. Urban gardens faced their share of potential intruders as well, both animal and human, and fences were an important element in defining urban public spaces such as commons, squares, roads, and parks [Fig. 18].

Fences were symbolic, as well as practical, boundaries.[9] Churchyards were often fenced, in part to protect them from wandering animals, and in part to demarcate the sacred space within. The similarity of yard-like enclosures created around family burials suggests an expression of the eternal domestic unit represented within. In both images and actual landscapes, fences around residences signified the division between personal property and the world beyond. This boundary made the presence and treatment of openings, such as gates, particularly important as they marked the passage between these realms of the public and the private (see Gate). Residential fences were also a visual statement of their owners’ resources and abilities. For example, in William Dering’s portrait of George Booth, the fence in the background divides the near and middle grounds [Fig. 19]. Dering extended the view into the distant, irregular landscape, but signaled the proprietor’s control over the space within the confines of his fence with the regular plantings and trimmed path. Countless representations of houses offer a similar demarcation, usually from the reverse perspective, showing the area surrounding the dwelling separated from the larger landscape by a fence. This division of domestic space is seen in modest gardens from Eunice Pinney’s Mother and Child in Mountain Landscape [Fig. 20] to more elaborate estates such as Janika de Fériet’s The Hermitage [Fig. 21].

Descriptions by travelers, such as Timothy Dwight, also demonstrate the significance of fences as an indication of the prosperity or decline of an area. Timothy Bigelow (1805) described the Shaker Village of Hancock, N.Y., as “much better fenced than any other in [the] vicinity.” With some pride, a writer in the Horticultural Register in 1836 found Maine wanting in comparison to Massachusetts since there was “not that attention paid to the appearance of fences about the dwellings, door yards, &c. as with us.” In something of an horticultural parable the Horticultural Register (1837) described the proprietor who spent all his money on his house leaving it to stand “dreary and alone . . . an unsightly broken fence to enclose it” while, with more foresight, “a more finished appearance is presented; the house is neatly painted . . . and a picket fence encircles it.”

--Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Rex, Charles, August 1641, instructions to Sir William Berkeley (quoted in Billings 1975: 56)

- “25. That they apply themselves to the Impaling of orchards and gardens for Roots and fruits, which that Country is so proper for and that every Planter be compelled for every 200 Acres Granted unto him to inclose and sufficiently Fence, either with Pales or Quick sett, and ditch, and so from time to time to preserve inclosed and Fenced a Quarter of an Acre of Ground in the most Convenient place near his dwelling house for Orchards and Gardens.”

- Fitzhugh, William, April 1686, in a letter to Dr. Ralph Smith, describing Greensprings, Va. (quoted in Lockwood 1934: 2:46)

- “the Plantation where I now live contains a thousand acres, grounds and fencing . . . a large orchard of about 2500 Apple trees most grafted, well fenced with a locust fence, which is as durable as most brick walls, a Garden, a hundred foot square, well pailed in, a Yeard wherein is most of the aforesaid necessary houses, pallizad’d in with locust Punchens which is as good as if it were walled in and more lasting than any of our bricks.”

- Penn, William, c. 1687, in a letter to James Harrison, inquiring about Pennsbury Manor, country estate of William Penn, near Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Thomforde 1986: 1)

- “I should be glad to see a draugh of Pennsberry wch an Artist would quickly take, wth ye land scip of ye hous, out houses, orchards, also wt grounds you have cleered wt improvemts made. an account how the peach & apple orchards grow; Bear. if any walks be made, & steps at ye water & how yt garden next ye water towards ye house, is layd out & thrives, how farr you advance . . . wt fence about ye yards gardens & orchards.”

- Virginia General Assembly, 23 October 1705, describing a legislative ruling in Virginia (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; hereafter CWF)

- “(I) Be it enacted . . . that if any horses, mares, cattle, hogs, sheep, or goats, shall break into any grounds, being inclosed with a strong and sound fence, four foot and half high, and so close that the beasts or kine breaking into the same, could not creep through; or with an hedge two foot high, upon a ditch of three foot deep, and three foot broad, or instead of such hedge, a rail fence of two foot and half high, the hedge or fence being so close that none of the creatures aforesaid can creep through, (which shall be accounted a lawful fence,) the owner . . . shall for the first trespass by any of them committed, make reparation to the party injured.”

- Anonymous, 4 August 1733, describing in the South Carolina Gazette a cemetery in Berkeley County, S.C. (CWF)

- “The new Burying Ground Fence to be done in the same manner it formerly was, the posts of both to be of the best light wood, Chinquepin or Cedar.”

- Ball, Joseph, February 1734, describing a property in Virginia (Library of Congress, Joseph Ball Letterbook)

- “The apple Nursery Fence must be kept upright good & strong, but set upon blocks, so that small hogs may go in, to keep down the weeds.”

- Kalm, Pehr, 21 September 1748 and 22 January 1749, describing fences in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York (1937: 1:47, 238–39)

- “The fences and pales are generally made here of wooden planks and posts. But a few good economists, having already thought of sparing the woods for future times, have begun to plant quick hedges round their fields; and for this purpose they take the above-mentioned privet, which they plant in a little bank that is thrown up for it.”

- “Fences. The fences built in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, but especially in New York, are those which on account of their serpentine form resembling worms are called ‘worm fences’* in English. The rails which compose this fence are taken from different trees, but they are not all of equal duration. . . . In order to make rails the people do not cut down the young trees . . . but they fell here and there large trees, cut them in several places, leaving the pieces as long as it is necessary, and split them into rails of the desired thickness; a single tree affords a multitude of rails. . . . Thus the worm fence is one of the most useful sorts of inclosures, especially as they cannot get any posts made of the wood of this county to last above six or eight years in the ground without rotting . . . the worm fences are easily put up again, when they are forced down. . . . Considering how much more wood the worm-fences require (since they zigzag) than other fences which go in straight lines, and that they are so soon useless, one may imagine how the forests will be consumed, and what sort of an appearance the country will have forty or fifty years hence.

“* The well-known zigzag fence of rails crossing at the ends. It is also called ‘snake fence’ or ‘Virginia rail fence.’

- Alexiowitz, Iwan, 1769, in a letter describing Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, vicinity of Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Darlington 1849: 50)

- “Thence we rambled through his fields, where the rightangular fences, the heaps of pitched stones, the flourishing clover, announced the best husbandry, as well as the most assiduous attention.”

- Anburey, Thomas, 20 January 1779, describing Jones’s Plantation, near Charlottesville, Va. ([1789] 1969: 2:323–24)

- “The fences and enclosures in this province are different from others, for those to the northward are made either of stone or rails let into posts, about a foot asunder; here they are composed of what is termed fence rails, which are made out of trees cut or sawed into lengths of about twelve feet, that are mauld or split into rails from four to six inches diameter.

- “When they form an inclosure, these rails are laid so, that they cross each other obliquely at each end, and are laid zig zag to the amount of ten or eleven rails in height, then stakes are put against each corner, double across, with the lower ends drove a little into the ground, and above these stakes is placed a rail of double the size of the others, which is termed the rider, which, in a manner, locks up the whole, and keeps the fence firm and steady.

- “These enclosures are generally seven or eight feet high, they are not very strong but convenient, as they can be removed to any other place, where they may be more necessary; from a mode of constructing these enclosures in a zig zag form, the New-Englanders have a saying, when a man is in liquor, he is making Virginia fences.”

- Cutler, Rev. Manasseh, 13 July 1787, describing the State House Yard, Philadelphia, Pa. (1987: 1:263)

- “The Mall is at present nearly surrounded with buildings, which stand near to the board fence that incloses it, and the parts now vacant will, in a short time, be filled up.”

- Brissot de Warville, J. P., 9 August 1788, describing the journey from Boston to New York, N.Y. (1792: 127–28)

- “But the uncleared lands are all located, and the proprietors have inclosed them with fences of different sorts. These several kinds of fences are composed of different materials, which announce the different degrees of culture in the country. Some are composed of the light branches of trees; others, of the trunks of trees laid one upon the other; a third sort is made of long pieces of wood, supporting each other by making angles at the end; a fourth kind is made of long pieces of hewn timber, supported at the ends by passing into holes made in an upright post; a fifth is like the garden fences in England; the last kind is made of stones thrown together to the height of three feet. This last is most durable, and is common in Massachusetts.”

- Bentley, William, 22 October 1790, describing Elias Hasket Derby Farm, Peabody, Mass. (1962: 1:180)

- “[231] 22. . . . The Principal Garden is in three parts divided by an open slat fence painted white, & the fence white washed. It includes 7/8 of an Acre. . . . The House is [lined?] with a superb fence, but is itself a mere country House, one story higher than common with a rich owner.”

- Moreau de Saint-Méry, M.L.E., 25 May 1794, describing the fences of houses in America (Roberts and Roberts, eds., 1947: 121–22)

- “In America almost everything is sacrificed to the outside view. To accomplish this the fences of the houses are sometimes varied by these six combinations: 1. Planks are laid vertically and close together. 2. Planks are laid the same way, with a space between them. 3. Little narrow boards are laid across without joining. 4. Vertically placed laths are joined. 5. Vertically placed laths are not joined. 6. Laths are placed vertically, but passing alternately on the outside and the inside of cross members. Further elegance is obtained by using different shades of paint on lattices and partitions.”

- La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, François-Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de, 1795–97, describing Norristown, Pa. (1800: 1:18)

- “Yet the uninterrupted and high fences of dry wood greatly disfigure the landscape, and produce a tedious sameness. These might be easily replaced by trees which endure the frost, as thorns are supposed here (I think without any just ground) to be unsuitable to the climate. Some of the fields along the road are bordered with traga or cedar, but these experiments are rare; and, in general, the land is inclosed with double fences of wood.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing New Haven Green, New Haven, Conn. (1821: 1:184)

- “Fences, and out-houses are also in the same style [neat and tidy]: and being almost universally painted white, make a delightful appearance to the eye; and appearance, not a little enhanced, by the great multitude of shade-trees: a species of ornament, in which this town is unrivalled.”

- Anonymous, 18 April 1800, describing in the Federal Gazette Willow Brook, seat of John Donnell, Baltimore, Md. (quoted in Sarudy 1989: 137)

- “That beautiful, healthy and highly improved seat, within one mile of the city of Baltimore, called Willow Brook, containing about 26 acres of land, the whole of which is under a good post and rail fence, divided and laid off into grass lots, orchards, garden.”

- Bigelow, Timothy, 1805, describing visit to Hancock Shaker Village, N.Y. (quoted in Hammond 1982: 201)

- “[The] lands (are) easily ascertained by the most transient observer; for they are more highly cultivated, laid out with more taste and regularity, and much better fenced than any other in their vicinity.”

- Drayton, Charles, 2 November 1806, describing the Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, Pa. (Drayton Hall, Charles Drayton Diaries, 1784–1820, typescript)

- “The Approach, its road, woods, lawn & clumps, are laid out with much taste & ingenuity. Also the location of the Stables: with a Yard between the house, stables, lawns of approach or park, & the pleasure ground or garden. The Fences seperating [sic] the Park-lawn from the Garden on one hand, & the office yard on the other, are 4 ft. 6 high. The park lawn is not in good order for lack of being fed upon. . . . Its 'fences where it is not visible from the house, is of common posts & rails. . . .

- “The former are made with posts & lathes—the latter with posts, rails & boards. They are concealed with evergreens hedge—of juniper I think.”

- Stebbins, William, 6 February 1810, describing the White House, Washington, D.C. (1968: 37)

- “Extended my walk alone to the President’s House:—a handsome edifice, tho’ like the capitol of free stone: the south yard principally made ground, bank’d up by a common stone wall: a plain picket fence on each side, the passage way to the house on the north: —some of the pickets lying on the ground.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, 29 July 1810, in letter to his son, Rembrandt Peale, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, Pa. (Miller, Hart, and Ward, eds., 1991: 3:55)

- “This View is taken at a point [from] the Tennants house a small distance, by which you see the Roof of the Mantion over the Garden fence which are of boards on a Stone Wall.”

- Lambert, John, 1816, describing Skenesborough, N.Y., and the Northern and Mid-Atlantic states (2:28–29, 231–32)

- “The other parts of the farms were covered with the stumps of trees, and enclosed by worm fences, which gave to these settlements a very rough appearance.”

- “A contrary practice is adopted in the northern and middle states, where a succession of farms, meadows, gardens, and habitations, continually meet the eye of the traveller; and if hedges were substituted for rail fences, those States would very much resemble some of the English counties.”

- Hulme, Thomas, 28 June 1818, describing the settlement of Morris Birkbeck, New Harmony, Ind. (quoted in Cobbett 1819b: 475)

- “910. I very much admire Mr. Birkbeck’s mode of fencing. He makes a ditch 4 feet wide at top, sloping to 1 foot wide at bottom, and 4 feet deep. With the earth that comes out of the ditch he makes a bank on one side, which is turfed towards the ditch. Then a long pole is put up from the bottom of the ditch to 2 feet above the bank; this is crossed by a short pole from the other side, and then a rail is laid along between the forks. The banks were growing beautifully, and looked altogether very neat as well as formidable; though a live hedge (which he intends to have) instead of dead poles and rails, upon top, would make the fence far more effectual as well as handsomer.”

- Green, Samuel, 13 May 1820, receipt for Hermitage, estate of Andrew Jackson, Nashville, Tenn. (Hermitage Collections, Andrew Jackson Papers: DLC 9967)

- “To putting up one hundred & twenty one pannel of post and rail cedar fence at half a dollar pr pannel, $60.50”

- Hening, William Waller, 1823, describing a legislative action by the Virginia General Assembly (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 138)

- “every freeman shall fence in a quarter of an acre of ground before Whitsuntide next to make a garden.”

- Waln, Robert, Jr., 1825, describing the Friends Asylum for the Insane, near Frankford, Pa. (p. 231).

- “In the rear of the wings are situated the yards or airing grounds, for the use of the male and female patients, separated by the space in the rear of the centre building, and each containing about five-ninths of an acre of ground, in grass, surrounded by walks. These are enclosed by board fences, ten feet in height, on the top of which is a simple, but effectual, apparatus for preventing escape of the patients. Boards about eight feet long and eight inches broad, and apparently forming part of the stationary fence, but detached from it, are placed around the whole circuit of the enclosure: these are connected to the fence beneath by hinges. Blocks of wood, about two feet long, are attached to these boards on the outside, at the lower part of which, are rings through which a strong wire is conducted: at the extremities of these wires alarum bells are attached. When the patient, in attempting to escape, seizes one of these moveable boards, it turns inwards on its hinges, the adventurer falls back into the yard, and the appendant blocks of wood, protruding, stretch the wire, and sound the alarm, which is distinctly heard through the building.”

- Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1830, describing Sweet Briar, seat of Samuel Breck, vicinity of Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Boyd 1929: 425)

- “Mr. Breck has taken considerable pains with a hedge of white hawthorn (Crataegus), which he planted in 1810, and caused to be plashed, stalked, and dressed last Spring by two Englishmen, who understood the business well. Yet he apprehends the whole of the plants will gradually decay, and oblige him to substitute a post and rail fence. Almost every attempt to cultivate a live fence in the neighborhood of Philadelphia seems to have failed. The foliage disappears in August, and the plant itself is short lived in our climate.”

- Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1830, describing Eaglesfield, country residence of John J. Borie, vicinity of Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Boyd 1929: 441)

- “The lawn is extensive, and divided from the house by a handsome chain fence, supported by posts painted green and very neatly turned. We notice this triple chained barrier, so light and beautiful, because we were informed that its price is as cheap as wood; to which, its graceful curve, and light appearance, render it every way superior.”

- Mason, General John, c. 1830, describing Gunston Hall, seat of George Mason, Mason Neck, Va. (quoted in Rowland, vol. 1, 1964, 100)

- “The isthmus on the northern boundary is narrow and the whole estate was kept completely enclosed, by a fence on that side of about one mile in length running from the head of Holt’s to the margin of Pohick Creek. This fence was maintained with great care and in good repair in my father’s time, in order to secure his own stock the exclusive range within it, and made of uncommon height, to keep in the native deer which had been preserved there in abundance from the first settlement of the country, and indeed are yet there in considerable numbers.”

- Ingraham, Joseph Holt, 1835, describing the villas and gardens along the Mississippi River (1:230)

- “An hour’s drive, after clearing the suburbs, past a succession of isolated villas, encircled by slender columns and airy galleries, and surrounded by richly foliaged gardens, whose fences were bursting with the luxuriance which they could scarcely confine, brought us in front of a charming residence.”

- B., J., 1 October 1836, “Horticulture in Maine” (Horticultural Register 2: 385)

- “Through the whole country, the substantials of life seem to be more attended to than ornament or the luxuries of horticulture.—There is not that attention paid to the appearance of fences about the dwellings, door yards, &c. as with us.”

- Adams, Rev. Nehemiah, 1842, describing Boston Common, Boston, Mass. ([Adams] 1842: 42–43)

- “The iron fence and brick side-walk which surround the Common are noble monuments of public enterprise and of the energy of American mechanics. The burial-ground formerly reached to the southern line of the Common. It was resolved to continue the mall through the burial-ground, but it was foreseen that, in doing it, public accomodation would interfere with the private and sacred attachment of individuals to their ancestral tombs. . . . [After the burials were moved] The mall was continued through the burial-ground to make the entire circuit of the Common. A slight and graceful iron fence was thrown around the tombs, and a rich and durable fence of the same material, with a brick wall outside, surrounding the whole Common, a circumference of five thousand eight hundred and sixty-seven feet, was begun and completed within six months.”

- Longfellow, Samuel, 3 September 1845, describing the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House, Cambridge, Mass. (quoted in Evans 1993: 1:40)

- “A buckthorn hedge has been made between us & Mr. Hastings, and Mr. Worcester not satisfied with the rustic open fence which separates between us demands a hedge there also which will cover up entirely the glimpse that I get from my western window and which I do not at all like to loose [sic].”

- Cleaveland, Nehemiah, 1847, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Mass. (quoted in Walter 1847: 20)

- “In 1844, the increasing funds of the corporation justified a new expenditure for the plain but massy iron fence which encloses the front of the Cemetery. This fence is ten feet in height, and supported on granite posts extending four feet into the ground. It measures half a mile in length, and will, when completed, effectually preserve the Cemetery inviolate from any rude intrusion. The cost of the gateway was about $10,000—the fence, $15,000.

- “A continuation of the iron fence on the easterly side is now under contract, and a strong wooden palisade is, as we learn, to be erected on the remaining boundary during the present year.”

- Notman, John, 1848, describing his designs for the Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Va. (quoted in Greiff 1979: 145)

- “The east hill should be planted densely, the plants may be of any kinds—better it should be overgrown with the common pine than remain in its present state; anything growing on that side would make the Cemetery seem more private, which is very desirable, as all who feel must know—and indeed it may be laid down as a rule, that all the exterior fences of a rural cemetery ought to be enveloped in shade of trees or young plantings of trees, else why do we fence our lots, or shut out the world’s otherwise, if not in grief—therefore, all along the east and west fences should be thickly planted, occasionally spreading out wide as I have marked upon the plan on these two lines.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., April 1848, describing pleasure grounds and farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, Pa. (American Journal of Insanity 4: 347, 349)

- “The pleasure grounds of the two sexes are very effectually separated on the eastern side, by the deer-park, surrounded by a high palisade fence, but the Park itself is so low that it is completely overlooked from both sides; and the different animals in it are in full view from the adjoining grounds used by the patients of both sexes. . . .

- “Between the north lodge and the deer-park, separated from the latter by a sunk palisade fence, is a neat flower garden. . . .

- “The fences that have been put up, were rendered necessary by the uses to which the different parts of the grounds were appropriated. A large part of the palisade fences, like those enclosing the deer-park and drying-yard, were to effect the separation of the sexes, and the close fences have been made, almost invariably, for the sole purpose of protecting the patients from observation, and giving them the proper degree of privacy.”

- Tuthill, Louisa C., 1848, describing New Haven Burying Ground, New Haven, Conn. ([1848] 1988: 337)

- “The ‘burying-ground’ at New Haven, Connecticut, has long been celebrated for its beauty. It has recently been enclosed with a massive wall on three sides, and a bronzed iron fence in front. The entrance is of free-stone, in the Egyptian style. . . . H. Austin architect.”

- Watson, John Fanning, 1857, describing the house of Israel Pemberton, Washington Square, and the house of William Bingham, Philadelphia, Pa. (1:375, 405, 414)

- “The low fence along the garden on the line of Third street, gave a full expose of the garden walks and shrubbery, and never failed to arrest the attention of those who passed that way.”

- “THIS beautiful square, now so much the resort of citizens and strangers, as a promenade, was, only twenty-five years ago, a ‘Potter’s Field.’ . . . It was long enclosed in a post and rail fence, and always produced much grass.”

- “The grounds generally he had laid out in beautiful style, and filled the whole with curious and rare clumps and shades of trees; but in the usual selfish style of Philadelphia improved grounds, the whole was surrounded and hid from the public gaze by a high fence.”

Citations

- Worlidge, John, 1669, Systema Agriculturae (pp. 85–86)

- “Seeing that Fencing, and Enclosing of Land is most evident to be a piece of the highest Improvement of Lands, and that all our Plantations of Woods, Fruits, and other Tillage, are thereby secured from external Injuries, which otherwise would lie open to the Cattel. . . . And also subject to the lusts of vile persons. . . .

- “For which reason we are obliged to maintain a good Fence, if we expect an answerable success to our Labors.”

- Marshall, Charles, 1799, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening (1:114–15, 124)

- “For hedges about a garden, (i.e. for the divisions of it) the laurel, yew, and holly are the principal evergreens: the former as a lofty and open fence, the second as close and moderate in height, and to be cut to any thing, the last as trainable by judicious pruning to an impregnable and beautiful fence. . . .

- “Here [about the house] should be also a good portion of grass plat, or lawnwhich so delights the eye when neatly kept, also borders of shewy flowers, which, if backed by any kind of fence, it should be hid with evergreens, or at least with deciduous shrubs, that the scene may be as much as possible vivacious.”

- Marshall, William, 1803, On Planting and Rural Ornament (1:258–59)

- “THE FENCE, where the place is large, becomes necessary: yet the eye dislikes constraint. Our ideas of liberty carry us beyond our species: the imagination feels a dislike in seeing even the brute creation in a state of confinement. Beside, a tall fence frequently hides, from the sight, objects the most pleasing; not only the flocks and herds, but the surface they graze upon. These considerations have brought the unseen fence into general use.”

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (pp. 80, 84)

- “That the boundary fence of a place should be concealed from the house, is among the few general principles admitted in modern gardening; but even in this instance, want of precision has led to error; the necessary distinction is seldom made between the fence which incloses a park, and those fences which are adapted to separate and protect the subdivisions within such inclosure. . . .

- “To describe the various sorts of fences suitable to various purposes, would exceed the limits and intentions of this work: every county has its peculiar mode of fencing, both in the construction of hedges and ditches, which belong rather to the farmer than the landscape gardener; and in the different forms and materials of pales, rails, hurdles, gates, &c.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (pp. 57, 65)

- “The [pleasure] ground should be previously fenced, which may be occasionally a hedge, paling or wall, &c. as most convenient. . . .

- “It being absolutely necessary to have the whole of the pleasure ground surrounded with a good fence of some kind, as a defence against cattle, &c. a foss being a kind of concealed fence, will answer that purpose where it can conveniently be made, without interrupting the view of such neighbouring parts as are beautified by art or nature, and at the same time affect an appearance that these are only a continuation of the pleasure=ground. Over the foss in various parts may be made Chinese and other curious and fanciful bridges, which will have a romantic and pleasing effect.”

- Main, Thomas, 28 September 1807, Directions for the Transplantation and Management of Young Thorn or Other Hedge Plants (pp. 37–38)

- “A promiscuous assemblage of several different kinds of plants in a hedge cannot be recommended; such a heterogeneous composition will neither make a good fence nor look handsome.

- “It may, however, be allowable for me to say, that this mode of fencing, whenever it is practised in the United States, will contribute its share to give an orderly and systematic turn to our plans of rural policy, conducive to a permanent neatness and regularity among arrangements that are commonly in a continual state of confusion and change.”

- Gregory, G., 1816, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (2:n.p.)

- “FENCE, in country affairs, a hedge, wall, ditch, bank, or other inclosure, made around gardens, woods, cornfields, &c. See HUSBANDRY. . . .

- “GARDENING. . . .

- “The situation of a garden should be dry, but rather low than high, and as sheltered as can be from the north and east winds. These points of the compass should be guarded against by high and good fences; by a wall of at least ten feet high; lower walls do not answer so well for fruit-trees, though one of eight may do. A garden should be so situated, to be as much warmer as possible than the general temper of the air is without, or ought to be made warmer by the ring and subdivision fences. This advantage is essential to the expectation we have from a garden locally considered.”

Images

Inscribed

Associated

Clarissa Deming, Orchard plan, after 1798.

George Ropes, Salem Common on Training Day, 1808.

Attributed

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, "Greenspring, home of William Ludwell Lee, James City County, Virginia," n.d.

William Dering, attr., Portrait of Anne Byrd Carter (Mrs. Charles Carter) (1725-1757), c.1742-1746.

William Dering, attr., Portrait of George Booth, 1748-1750.

Charles Willson Peale, Parnassus, c.1769.

John Nancarrow, "Plan of the Seat of John Penn jun’r: Esqr: in Blockley Township and County of Philadelphia," c.1784.

Cornelius Tiebout, "A View of the present Seat of His Excel. the Vice President of the United States," 1790.

Samuel McIntire, Design for a Fence, c.1791.

- 0085.jpg

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, "York River, looking N.W. up to West Point," 1797.

Amy Cox, Box Grove, c.1800.

Michele Felice Cornè, Ezekiel Hersey Derby Farm, c.1800.

John Archibald Woodside, Lemon Hill, 1807.

Charles Willson Peale, View of the Garden at Belfield, 1816.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, "Plan of the public Square in the city of New Orleans, as proposed to be improved . . ." [detail], March 20, 1819.

Janika de Fériet, The Hermitage, c.1820.

Arthur J. Stansbury, City Hall Park, From the Northwest Corner of Broadway and Chambers Street, c.1825.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Castle Garden, N. York, c.1825-1828.

W. J. Bennett, Broad Way from the Bowling Green, c.1826.

- 0105.jpg

Joseph Jacques Ramée, Thierry Frerese (lithographer), Title page of Recueil de cottages et maisons de campagne (1837).

W. H. Bartlett, "Washington from the President's House," in Nathaniel Parker Willis, American scenery; or, Land, lake, and river illustrations of transatlantic nature... Vol. II (1840), opp. p. 50.

Robert Mills, “Picturesque View of the Building, and Grounds in front,” 1841.

Charles H. Wolf, attr., Pennsylvania Farmstead with Many Fences, c.1847.

Robert P. Smith, "View of Washington," c.1850.

Notes

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), 84.

- ↑ For a more detailed discussion of fence types, see Vanessa Patrick, “Partitioning the Landscape,” Colonial Williamsburg Research Report(Williamsburg, Va.: Williamsburg Foundation, 1983); Elizabeth Wilkinson and Marjorie Henderson, eds., Decorating Eden: A Comprehensive Sourcebook of Classic Garden Details (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1992), 42–69; Wilbur Zelinsky, “Walls and Fences,” in Changing Rural Landscapes, ed. Ervin H. and Margaret J. Zube (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1977), 53–63 [reprinted from Landscape 8, no. 3 (1959)].

- ↑ Patrick, “Partitioning the Landscape,” 2, 16.

- ↑ While treatise and dictionary definitions of “fence” list stone and brick as building materials, it was common practice in America to refer to stone and brick barriers as walls. In 1871, the first year for which statistics were kept, a study of fence types in New England revealed that stone fences ranged from 32 percent in Vermont and 33 percent in Connecticut to 67 percent in Maine and 79 percent in Rhode Island (see Zelinsky, “Walls and Fences,” 59).

- ↑ At Westover, research has revealed that the iron-gate was originally painted white (Carl Lounsbury, personal communication).

- ↑ See Gregory K. Dreicer, “Wired! The Fence Industry and the Invention of Chain Link,” in Between Fences, ed. Gregory K. Dreicer (Washington, D.C.: National Building Museum; New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), 71.

- ↑ Robert Emlen, Shaker Village Views: Illustrated Maps and Landscape Drawings by Shaker Artists of the Nineteenth Century (Hanover, N.H., and London: University Press of New England, 1987), 8.

- ↑ William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983), 130–31.

- ↑ The functions, both symbolic and practical, of fences have been explored in an exhibition and catalogue organized and edited by Gregory K. Dreicer, Between Fences, cited in note 6.