Alcove

Discussion

As early as 1787, Americans recognized the alcove as a distinct garden feature that could follow one of two types: an ornamental building in a garden or a recessed niche cut into live plant material. As a garden building, an alcove could be a freestanding or semidetached structure, typically possessing three sides and housing a seat. Alcoves provided shelter from the sun in summer but were particularly welcome in the northern winter, since they were often enclosed against the winds and open to the sun.

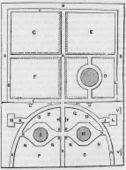

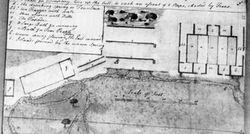

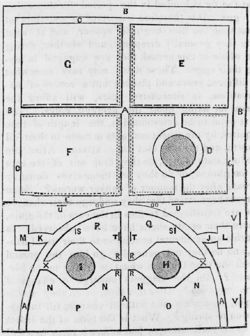

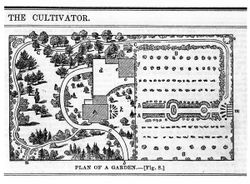

As sheltered sun-catchers, alcoves were logical appendages to bathhouses as indicated in Samuel Vaughan's 1787 plan of Berkeley Springs, Va. (later W.Va.) [Fig. 1]. Like other garden buildings, such as summerhouses and pavilions, alcoves provided shade and gave visual and physical structure to the garden by serving “as terminations to grand walks,” as Eliza Caroline Burgwin Clitherall (active 1801) and Bernard M’Mahon (1806) both explained. Alcoves, situated at the end of long walks or avenues, created visual focal points and secluded destinations for people using the garden [Fig. 2].

When conceived as a recessed niche, an alcove was typically set into or cut out of densely planted vegetation, such as privet. Alexander Walsh’s 1841 account of diminutive alcoves exemplifies this second type [Fig. 5]. In Walsh’s plan, the alcoves act as portals between the ornamental pleasure ground and compartments devoted to flowers and culinary vegetables (see also M’Mahon 1806). These portals were elevated, much like those described in the Horticultural Register of 1837, and thus provided both enclosure and privacy as well as a vantage point from which to view the landscape.

-- Anne Helmreich

Images

Inscribed

Solomon Drowne, Plan of a botanic garden at Brown University, n.d.

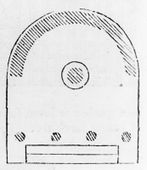

William and John Halfpenny, "A Chinese Alcove Seat Fronting Four Ways," in Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste (1755), pl.8.

Samuel Vaughan, Plan of Bath (Berkeley Springs) Va., 1787.

J.C. Loudon, "Alcoves," in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), p.356, fig.331.

Alexander Walsh, "Plan of a Garden," in New England Farmer 19, no. 39 (Mar. 31, 1841): 308.

Associated

Anonymous, "A Rustic Alcove," in A.J. Downing, ed. Horticulturist 2, no. 8 (Feb 1848): pl. opp. p.345, fig.4.

Texts

Common Usage

- Constantia [pseud.], 24 June 1790, describing Gray's Garden, Philadelphia, Pa. (Massachusetts Magazine 3: 415)[1]

- "At every turn shaded seats are artfully contrived, and the ground abounds with arbours, alcoves, and summer houses, which are handsomely adorned with odoriferous flowers. Among these the little federal temple claims the principal regard. It is the very edifice, that upon the celebration of the ratification of the constitution, was carried in triumphant procession through the streets of this metropolis; and, upon a gentle acclivity, upon the summit of a green mound infixed, it hath now obtained a basis. It is a Rotunda, its cupola is supported by thirteen pillars handsomely finished; their base, is to receive the cypher of the several states, which they represent, with a star upon every capital, and its top is crowned with the figure of Plenty grasping the cornucopia and other insignia. The ascent to this Temple is easy, and we gain it by the semicircular steps neatly turned, and the view therefrom is truly interesting."

- Clitherall, Eliza Caroline Burgwin, active 1801, describing the Hermitage, seat of John Burgwin, Wilmington, N.C. (quoted in Flowers 1983: 126)[2]

- "These [gardens] were extensive and beautifully laid out. There was alcoves and summer houses at the termination of each walk, seats under trees in the more shady recesses of the Big Garden, as it was called, in distinction from the flower garden in front of the house."

- Walsh, Alexander, 1 February 1841, "Remarks on Ornamental Gardening" (New England Farmer 19: 309)

- "diminutive rustic alcoves, from thrifty growing plants of upright privet, Ligustrum strictum, formed by placing a platform of light boards 2 ft. 6 in. from the ground, and 3 ft. long, and 1 ft. 6 in. wide, on the twigs of the privet; those in the centre of the platform to be trimmed off close to it under side, and those on the back and sides to be led up round the platform, entwined and arched; the door to be constructed from the twigs in front, and an opening left 2 ft. 6 in. high, which is the height of the dome." [Fig. 3]

Citations

- M'Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener's Calendar (p. 64)[3]

- "In some spacious pleasure-grounds various light ornamental buildings and erections are introduced, as ornaments to particular departments; such as temples, bowers, banquetting houses, alcoves, grottos, rural seats, cottages, fountains, obelisks, statues, and other edifices; these and the like are usually erected in the different parts, in openings between the divisions of the ground, and contiguous to the terminations of grand walks, &c.

- "Some of these kinds of ornaments, however, being very expensive, are rather sparingly introduced . . . other parts present alcoves, bowers, grottos, rural-seats, &c. at the termination of different walks."

- Loudon, J. C., 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 356)[4]

- "1810. Alcoves . . . are used as winter resting places, as being fully exposed to the sun." [Fig. 4]

- Anonymous, 1 April 1837, "Landscape Gardening" (Horticultural Register 3: 129)

- "Architectural and other ornaments may be introduced, according to the means of the proprietor. When properly distributed they add much to the effect. Seats and arbors should be placed at points affording interesting views, alcoves and rotundas on eminences, and hermitages in secluded places."

- Thomas, John J., Jan. 1842, "The Garden and the Orchard" (The Cultivator 1: 22)

- "The two finest views are seen after entering the house;… The view from the dining room is towards the garden. Directly beneath is the parterre, or flower beds cut into the turf on the lawn, at k; beyond this is the light archway gate to the garden, through which the view extends along the vista formed by flower beds, h h, and terminates at the green house, (or alcove), at m.” [Fig. 5]

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (p. 26)[5]

- "ALCOVE, is a seat in a recess, formed of stone, brick, or other dead material, and so constructed as to shelter the party seated from the north and other colder quarters, whilst it is open in front to the south."

- Webster, Noah, 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language (p. 32)[6]

- "AL'COVE, AL-COVE, n. [Sp. alcoba, composed of al, with the Ar. . . . kabba, to arch, to construct with an arch, and its derivatives, an arch, a rounded house; Eng. cubby.] . . .

- "3. A covered building, or recess, in a garden.

- "4. A recess in a grove."

Notes

- ↑ Constantia. 1790. "Description of Gray's Gardens, Pennsylvania." Massachusetts Magazine 3 (June): 413–17. view on Zotero

- ↑ Flowers, John. 1983. “People and Plants: North Carolina’s Garden History Revisited.” Eighteenth Century Life 8, no. 2 (January): 117–29. view on Zotero

- ↑ M'Mahon, Bernard. 1806. The American Gardener's Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a complete account of all the work necessary to be done . . . for every month of the year. . . . Philadelphia: B. Graves for the author. view on Zotero

- ↑ Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius). 1826, 1834, 1850. An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening. 4th ed. London: Longman et al. view on Zotero

- ↑ Johnson, George William. 1847. A Dictionary of Modern Gardening. Edited by David Landreth. Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard. view on Zotero

- ↑ Webster, Noah. 1828. An American Dictionary of the English Language. 2 vols. New York: S. Converse. view on Zotero