Obelisk

The term obelisk was used in the American colonies and early Republic to refer to a slender shaft or pillar with four faces that diminished in width from the base to a pyramidal top. Obelisks were generally made of wood, granite, marble, or, as Jefferson prescribed for his tombstone, "coarse stone."

Discussion

The term obelisk was used in the American colonies and early Republic to refer to a slender shaft or pillar with four faces that diminished in width from the base to a pyramidal top. Obelisks were generally made of wood, granite, marble, or, as Jefferson prescribed for his tombstone, "coarse stone." According to Batty Langley in New Principles of Gardening (1728), they could also be made of trellis work and covered with climbing plants to give the effect of a living obelisk. Some obelisks were placed upon pedestals that were cube or temple forms; others rose directly from the ground.

In the designed landscape, the obelisk served two functions: as a garden ornament and as a monument with emblematic significance. Obelisks were important in the designed landscape or pleasure garden because they punctuated the vista or provided a place from which to gain a view. In order to serve these purposes, treatise authors recommended placing obelisks on elevated sites, although this treatment was not always used. Obelisks, which varied in size, were placed either in the center of open spaces or at the terminus of circulation routes. In both cases, they served as focal points. They often appeared in openings where radial sight lines were clear, as indicated by Hannah Callender in her 1762 description of Judge William Peters's estate, Belmont Mansion, near Philadelphia, where she wrote that the avenue "looks to the obelisk."

In nineteenth-century America, the obelisk was utilized on a monumental scale in public landscape design. Some examples were built as hollow shafts that could be ascended by means of an internal staircase leading to interior lookout platforms or external galleries, allowing the visitor a panoramic view of the surrounding landscape.[1] Solomon Willard's Bunker Hill Monument in Boston was the earliest obelisk of this type, dating from 1825 [Fig. 1].[2] Monumental obelisks were also striking landmarks in the relatively low urban skylines of the first half of the nineteenth century. [[Robert Mills[[, architect of the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., designed several monumental obelisks that served both as observation towers and civic displays.[3]

The obelisk's rich antique associations imbued it with symbolic significance. Its origins in Egypt, prominence in the Roman world, and, since the Renaissance, use in gardens and parks lent a vocabulary of the exotic and the historic to American landscape design. Several collected treatise citations recount the best-known examples of ancient obelisks, many of which have survived into the modern period. Excavations in Rome during the seventeenth century, for example, revealed dozens of Egyptian obelisks that were reerected throughout the city. At the same time, modern obelisks ornamented French gardens such as Versailles. Many great gardens in Britain in the eighteenth century also featured obelisks: Castle Howard, Chiswick House, Holkham Hall, and Montacute House, to name a few.[4] With the French invasion of Egypt in 1798, the taste for Egyptian statuary and styles increased and obelisks appeared more frequently as props in gardens.[5] Thus the tradition of obelisks in European gardens and public spaces transmitted via literature, European designers, and American visitors abroad, was a significant influence on American garden practice. Both Ephraim Chambers (1741–43) and Noah Webster (1828) described the use of hieroglyphic inscriptions on obelisks that expressed the historic tradition from which the form derived.

In America, the choice of the obelisk for political commemoration in public spaces was recorded in the revolutionary period at Williamsburg, Va., where the monument was intended to honor those who opposed the Stamp Act. The repeal of that act was celebrated by the erection of a temporary obelisk in the Boston Common, as illustrated in a print by Paul Revere [Fig. 2]. After the War of Independence, Pierre-Charles L'Enfant specified obelisks as decorations in the new capital city that would memorialize the heroes of the Revolution. His plan of 1792 indicated these monuments embellishing the public squares of the new capital. The association with republican Rome, the site of many obelisks, was a frequent iconographic reference in early federal decoration and rhetoric. The obelisk was a popular public and political monument, as Robert Mills argued, not only because of its association with antiquity and republicanism, but also because its surfaces allowed inscriptions that could particularize the memorial function. He described, for example, how the ornamentation on his design for the Bunker Hill obelisk symbolized the states' formation of the federal union.

The Egyptian obelisk was appropriate for the expression of early national symbolism because of the equation of the newly formed United States with another "first civilization." Freemasonry also fostered the link with ancient Egypt. The obelisk exemplified "cubic architecture" preferred by the Burlington circle of Freemason architects, derived from Palladio and James Gibbs and practiced in America by Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Henry Latrobe. It was seen as a repudiation of baroque eclecticism, as well as colonial red-brick Anglo-Dutch architecture. For American Freemasons, building took on a political cast that extended into the garden.[6]

Mills pointed out that its diminishing width made the obelisk lighter and more graceful than another popular monument form, the column. Solomon Willard preferred the obelisk to the column, the latter being too "splendid." It was both the picturesque effect as well as the historical significance of the obelisk that motivated J.C. Loudon's recommendation of it in the garden.

The wave of monument building and civic improvement that marked the early Federal period carried with it an increasing number of obelisks. Chevalier Charles François Adrien le Parlmier d'Annemours estate, Belmont, in Baltimore, featured an obelisk built in honor of Christopher Columbus; and Ashley Hall in Charleston, S.C., displayed one in memory of Lt. Gov. William Bull [Fig. 3].

The visual and textual evidence surrounding Charles Willson Peale's obelisk represents a clear correlation between usage, treatise citation, and image based on early American primary sources. Peale noted his reliance on G. Gregory's definition in the Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1806–7, 1816) in building an obelisk in his garden at Belfield. Gregory's description gave the proportions and dimensions of the "truncated, quadrangular, and slender pyramid" that Peale sketched in his letters and inscribed on an obelisk [Fig. 4]. The emblematic significance of this obelisk was also suggested in Gregory's treatise description of the obelisk built to memorialize Ptolemy Philadelphus, the ancient Egyptian who built the great obelisk lighthouse and library at Alexandria, and after whom Peale of Philadelphia may have been modeling himself.

Jefferson and Peale's garden obelisks served private but also commemorative purposes as both men planned to use the forms garden features that would eventually become their tombstones. In each case, these public figures mixed political and private associations in their choice of inscriptions. In addition to the political significance, the use of the Egyptian obelisk for funereal ornamentation was well established in America. The discussion surrounding the designs for Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Mass., conveyed the popular interest in Egyptian-style monuments and architecture in early rural cemeteries. Defenders of the plans for the cemetery called it an "architecture of the dead" because nearly all surviving Egyptian architecture or monuments had a funerary purpose.[7] The Egyptian practice of placing the tomb "in the midst of the beauty and luxuriance of nature"[8] was also cited as justification for this new garden type. [Figs. 5 and 6]. The obelisk had a long and continuous tradition in American landscape design that began in the colonies and lasted well into the nineteenth century. The feature was utilized in both public and private gardens ranging in scale from a few feet to the tallest edifices in American architecture until the advent of the skyscraper. Obelisks persisted over time despite changes in garden styles, finding a place within the Anglo-Dutch landscapes of Williamsburg, Va., in the mid-eighteenth century, as well as in the picturesque landscapes of rural cemeteries one hundred years later.

-- Therese O'Malley

Images

Inscribed

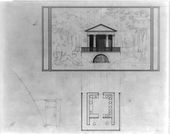

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Houses and a church. Garden plan with outbuildings, 1795-1799.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Houses and a church. Spring house - elevation and plan, 1795-1799.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, "Taste. Anno 1620," in "Essay on Landscape" (1798-1799).

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Studies of Trees, in "Essay on Landscape" (1798-1799).

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Studies of Trees, in "Essay on Landscape" (1798-1799).

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Plan of the Capitol grounds, 1815.

Texts

Common Usage

- Callender, Hannah, 1762, describing Belmont Mansion, estate of Judge William Peters, near Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Vaux 1888: 455)[9]

- “A broad walk of English Cherry trees leads down to the river. The doors of the house opening opposite admit a prospect of the length of the garden over a broad gravel walk to a large handsome summer house on a green. From the windows a vista is terminated by an obelisk. On the right you enter a labyrinth of hedge of low cedar and spruce. In the middle stands a statue of Apollo. In the garden are statues of Diana, Fame and Mercury with urns. We left the garden for a wood cut into vistas. In the midst is a Chinese temple for a summer house. One avenue gives a fine prospect of the City. . . . Another avenue looks to the obelisk.”

- Anonymous, 11 December 1766, describing in the Virginia Gazette a decision to erect an obelisk in Williamsburg, Va. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; hereafter CWF)

- “Occassioned by a Resolution of the Honourable House of Burgesses in Virginia, to erect an Obelisk in Memory of those illustrious Patriots who distinguished themselves in Parliament, by their spirited Opposition to the Stamp-Act.”

- Anonymous, 19 May 1776, describing in the Boston Gazette Boston Common, Boston, Mass. (quoted in Brigham 1954: 21)[10]

- “[to] be exhibited on the Common, an Obelisk—A Description of which is engraved by Mr. Paul Revere; and is now selling by Edes & Gill.”

- Anonymous, 22 May 1776, describing in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston News-Letter Boston Common, Boston, Mass. (quoted in Brigham 1954: 22)[10] back up to text

- “At Eleven o’clock the Signal being given by a Discharge of 21 Rockets, the horizontal Wheel on the Top of the Pyramid or Obelisk was play’d off, ending in the Discharge of sixteen Dozen of Serpents in the Air, which concluded the Shew.”

- Bartram, William, 1789, describing settlements of the Muscogulge and Cherokee Indians (1996: 561–62)[11]

- “PLAN OF THE ANCIENT CHUNKY-YARD.

- “The subjoined plan . . . will illustrate the form and character of these yards. [Fig. 7]

- “A, the great area, surrounded by terraces or banks.

- “B, a circular eminence, at one end of the yard, commonly nine or ten feet higher than the ground round about. Upon this mound stands the great Rotunda, Hot House, or Winter Council House, of the present Creeks. It was probably designed and used by the ancients who constructed it, for the same purpose.

- “C, a square terrace or eminence, about the same height with the circular one just described, occupying a position at the other end of the yard. Upon this stands the Public Square.

- “The banks inclosing the yard are indicated by the letters b, b, b, b; c indicate the “Chunk-Pole,” and d, d, the “Slave-Posts.”

- “Sometimes the square, instead of being open at the ends, as shown in the plan, is closed upon all sides by the banks. In the lately built, or new Creek towns, they do not raise a mound for the foundation of their Rotundas or Public Squares. The yard, however, is retained, and the public buildings occupy nearly the same position in respect to it. They also retain the central obelisk and the slave-posts.”

- Pierre-Charles L'Enfant\L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, 4 January 1792, from notes on “Plan of the City,” describing Washington, D.C. (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 165)[12]

- “The Center of each Square will admit of Statues, Columns, Obelisks, or any other ornament such as the different States may choose to erect: to perpetuate not only the memory of such individuals whose Counsels, or military achievements were conspicuous in giving liberty and independence to this Country; but also those whose usefulness hath rendered them worthy of general imitation: to invite the youth of succeeding generations to tread in the paths of those Sages, or heroes whom their Country has thought proper to celebrate.”

- Anonymous, 17 August 1792, describing in the Claypole’s Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia) Belmont, country seat of Chevalier Charles François Adrien le Parlmier d’Annemours, Baltimore, Md. (quoted in Thompson 1906: 246)[13]

- “[Charles François Adrien Le Parlmier d’Annemours built] an obelisk to honour the memory of that immortal man—Christopher Columbus . . . in a grove in one of the gardens of the villa . . . on the 3rd of August, 1792, the anniversary of the sailing of Columbus from Spain.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing New Haven Burying Ground, New Haven, Conn. (1821: 1:192)[14]

- “The monuments in this ground are almost universally of marble; in a few instances from Italy; in the rest, found in this and neighbouring States. A considerable number are obelisks; others are tables; and others, slabs, placed at the head and foot of the grave. The obelisks are placed, universally, on the middle line of the lots; and thus stand in a line, successively, through the parallelograms.”

- Moore, Thomas, 1804, describing Washington, D.C. (quoted in Reps 1965: 257)

- “This embryo capital, where fancy sees

- “Squares in morasses, obelisks in trees;

- “Which second-sighted seers, ev’n now, adorn

- “With shrines unbuilt, and heroes yet unborn,

- “Though naught but woods and Jefferson they see,

- “Where streets should run and sages ought to be.”

Anonymous, 2 July 1804, describing Vauxhall

Gardens, New York, N.Y. (New York Daily

Advertiser)

“At 8 o’clock will commence the most complete

illumination, consisting of upwards of four

thousand Colored Lamps, and decorated . . . with

Pyramids, Obelisks, Arches, &c.”

Peale, Charles Willson, 12 November 1813, in

a letter to his daughter, Angelica Peale Robinson,

describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson

Peale, Germantown, Pa. (Miller, Hart, and Ward,

eds., 1991: 3:216)

“I have made an Oblisk to terminate a Walk in

the Garden, read in Dictionary of Arts for description

of them. I made it of rough boards & white

washed it with lime & allum—The allum It is said

will convert the lime in time to Stone. I have put

the following motto on it—on one side ‘Never

return an Injury, It is a noble Triumph to overcome

Evil by Good.’ another, ‘Labour while you

are able it will give health to the Body—peaceful

content to the mind.’ another, ‘He that will live in

peace & Rest, must hear, and see, and say the best

& in french ‘y voy, & te tas, si tu veux vivre en

paix.’ and on another ‘Neglect no Duty.’ The

distick which I have adopted is claimed by several

Nations, I have put the french because it is more

concise & equally expressive.”

Notes

- ↑ John Zukowsky, "Monumental American Obelisks: Centennial Vistas," Art Bulletin 58 (December 1976): 574–81. view on Zotero

- ↑ Zukowsky argues that the American monumental obelisk was a combination of the solid obelisk and the hollow memorial column. As it developed through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the monumental obelisk was a formally unique and distinctly American monument type that had military connotations and served as an image of continental expansion and unity during the centennial era. See Zukowsky, "Monumental American Obelisks," 581.

- ↑ Mills designed four monumental obelisks during his career. Pamela Scott, "Robert Mills and American Monuments," in Robert Mills, Architect, ed. John M. Bryan (Washington, D.C.: American Institute of Architects Press, 1989), 143–77. view on Zotero

- ↑ Geoffrey Jellicoe et al., eds., Oxford Companion to Gardens (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 408. view on Zotero

- ↑ For information on the Egyptian style in America, see Richard G. Carrott, The Egyptian Revival: Its Sources, Monuments, and Meaning, 1808–1858 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978). view on Zotero

- ↑ Roger Kennedy, Orders from France (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990), 431. view on Zotero

- ↑ Mount Auburn Cemetery was originally to be named the "American Père Lachaise." Although the name was not given, Mount Auburn Cemetery was often compared with Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Richard Etlin recounts the history of this French cemetery as an influential landscape continued in America. He discusses the Egyptian style of much of that cemetery's architecture and monuments. See Richard Etlin, The Architecture of Death: The Transformation of the Cemetery in Eighteenth-Century Paris (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1984), 358–68. view on Zotero

- ↑ Blanche Linden-Ward, Silent City on the Hill: Landscapes of Memory and Boston's Mount Auburn Cemetery (Columbus: Ohio State University, 1989), 261–66. view on Zotero

- ↑ Vaux, George. “Extracts from the Diary of Hannah Callender.” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 12, no. 1 (1888): 432–56. view on Zotero

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Brigham, Clarence. Paul Revere’s Engravings. Worcester, Mass.: American Antiquarian Society, 1954. view on Zotero

- ↑ Bartram, William. Travels, and Other Writings. New York: Library of America, 1996. view on Zotero

- ↑ Caemmerer, H. Paul. The Life of Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, Planner of the City Beautiful, The City of Washington. Washington, D.C.: National Republic, 1950. view on Zotero

- ↑ Thompson, Henry F. “The Chevalier D’Annemours.” Maryland Historical Magazine 1 (1906): 241–46. view on Zotero

- ↑ Dwight, Timothy. Travels in New England and New York. 4 vols. New Haven, Conn.: T. Dwight, 1821. view on Zotero