Porch

History

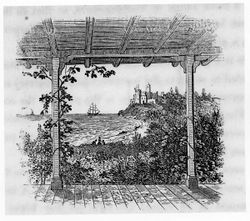

Porch is one of several words (including piazza, portico, and veranda) used to describe covered walks or spaces supported by columns or piers and attached to, or to part of, a building. This architectural feature spoke to the interrelatedness of architecture and gardens, a relationship that grew out of the romantic interest in landscape characterizing the aesthetics of the 18th and 19th centuries. Two images exemplify the importance of these structures in creating and framing views of the garden and landscape. The first is a drawing of York Island, Long Island, by William Russell Birch (1808), who explained that the view was taken from the piazza, a place from which one could see “innumerable seats, spreading over an extensive country which glittered as the sun arose” [Fig. 1].[1] The second is from A. J. Downing’s book on wooden picturesque houses, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850) [Fig. 2]. Both illustrate views from the bracketed piazza, or veranda, as Downing preferred to call it, out to the distant prospect. Two points are important in the history of these terms: First, these architectural elements served to elide the boundaries of the garden and building by linking interior and exterior space both visually and physically. Second, the associative values of refinement and domesticity, and even national progress, were read into the forms.

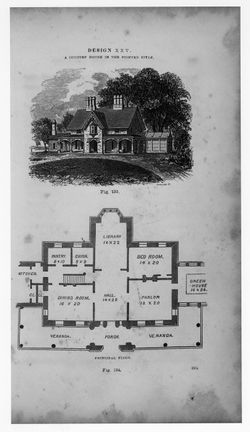

Treatises often used these terms interchangeably, along with a few other less common words that were more or less synonymous. Downing and Alexander Jackson Davis used the term “umbrage” to refer to the same feature on a house, implying a place of shade;[2] Downing used the term “pavilion” synonymously with “veranda”[3]; and Mary Elizabeth Latrobe mentioned that in New Orleans the piazza was also known as the gallery (view text). Contrasting usage sometimes reveals distinctions. In his plan for a country house, Downing also used the term “porch” to identify the central area of the veranda leading to the entryway. The 19th-century architect William H. Ranlett sometimes distinguished between piazza and veranda, using “piazza” for a walk over which a projecting roof might be added, and “veranda” for a structure that included a roof (). Two points are important in the history of these terms: First, these architectural elements served to elide the boundaries of the garden and building by linking interior and exterior space both visually and physically. Second, the associative values of refinement and domesticity, and even national progress, were read into the forms.

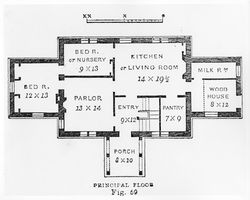

The term “porch” was defined in the 1828 dictionary entry by Noah Webster as referring to a roofed architectural element often supported by columns or piers, either attached to a building or existing as an independent garden structure (view text). During the colonial and early Republic periods three kinds of porches were evident throughout America. First, the porch was either an open or enclosed projecting roofed area of a building that sheltered a doorway or entrance [Fig. 3]. Since most gardens were situated next to the house, a porch was often a point of access from the house to the ornamental grounds. Eliza Caroline Burgwin Clitherall (active 1801) depicted such a porch at the Hermitage in Wilmington, North Carolina. [See Fig. 5].

The second meaning of the term referred to a covered sitting and viewing area that was either attached to the building or was free-standing. In describing the use of porches as “decorative marks to the entrances of scenes” (akin to those of a theater proscenium), J. C. Loudon was referring to their use as embellished shelters over benches or seats placed in the garden (view text). Downing’s illustration of the rustic porch at Montgomery Place, on the Hudson River in Dutchess County, New York, suggests that, in addition to punctuating or shaping garden scenery, as Loudon recommended, porches, if appropriately placed and decorated, could function as seats and pavilions did, directing the viewer’s attention to a offered a way to view or prospect [See Fig. 7][4]. Its function also allowed those seated to observe the landscape in all kinds of weather, as described in 1749 by Pehr Kalm. Downing’s porches make clear the function of the porch as a mediator between interior and exterior realms. He praised porches that were covered with vegetation for easing the transition from outside to inside, and for providing evidence of the cultivated domesticity within the home [Fig. 4].

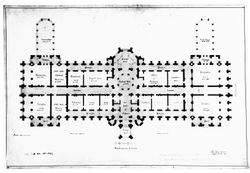

The third kind of porch is described by Downing as the carriage porch, or porte cochère, where in a grand home the arriving guests drew up under an architectural canopy for shelter. John Notman similarly inscribed the term porte cochère on his unexecuted design for the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC [See Fig. 6]. He includes porches for the side entrances and piazzas for galleries running along the façades.

—Therese O’Malley

Texts

Usage

- House of Burgesses, 1701, describing the Capitol, Williamsburg, VA (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 286)[5]

- “[It was ordered that] the porches of the said Capitol [in Williamsburg] be built circular fifteen foot in breadth from outside to outside, and that they stand upon cedar columns.”

- Kalm, Pehr, June 21, 1749, describing Albany, NY (1937: 1:341)[6]

- “The front doors are generally in the middle of the houses, and on both sides are porches with seats, on which during fair weather the people spend almost the whole day, especially on those porches which are in the shade. . . . In the evening the verandas are full of people of both sexes.”

- Orphans Court, 1795, describing an orphan’s estate in Worcester County, MD (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 286)[5]

- “. . . framed dwelling house . . . [with] a porch or piazza on the easternmost side of the house about 21 feet long by 7 feet wide plank floor with seats.”

- Clitherall, Eliza Caroline Burgwin (Caroline Elizabeth Burgwin), active 1801, describing the Hermitage, seat of John Burgwin, Wilmington, NC (quoted in Flowers 1983: 125)[7]

- “You have seen the picture representing the Hermitage, Tho’ in appearance it fell far behind Alveston or Ashley [English estates belonging to Burgwin relatives]. . . . a large handsomely finish’d room the middle door opening to a porch, leading to the front garden, on either side of this room, were glass doors opening upon the Piazza to each wing.” [Fig. 5].

- Anonymous, 1803, describing in The Virginia Herald a property for rent in Fredericksburg, VA (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 286)[5]

- “. . . commodious close porch in front, and an open portico in the rear.”

- Barber, John Warner, and Henry Howe, 1844, describing Mount Holly, NJ (1844: 112)[8]

- “Some porches still remain, on the more ancient dwellings, to revive the recollection of the social manners which once prevailed, when neighbors freely and unceremoniously visited from house to house, taking the porches for their sittings and conversation. They were the delight of the young, for they facilitated visits and acquaintances between the sexes. The moderns scout them, even while they desire their use.”

- Notman, John, December 26, 1846, describing his designs for the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (quoted in Greiff 1979: 119)[9]

- “No. 5 is the north front; on this is seen the carriage porch elevation, a structure necessary to comfort in a building of so many purposes.” [Fig. 6]

- Downing, A. J., October 1847, describing Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (Horticulturist 2: 157) back up to history

- “Not long after leaving the rustic pavilion, on descending by one of the paths that diverges to the left, we reach a charming little covered resting place, in the form of a rustic porch. The roof is prettily thatched with thick green moss. Nestling under a dark canopy of evergreens in the shelter of a rocky fern-covered bank, an hour or two may be whiled away within it, almost unconscious of the passage of time.” [Fig. 7].

Citations

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 2:n.p.)[10]

- “PORCH. n.s. [porche, Fr. porticus, Lat.]

- “1. A roof supported by pillars before a door; an entrance.

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 356)[11] back up to history

- “1809. Porches and porticoes . . . are sometimes employed as decorative marks to the entrances of scenes; and sometimes merely as roofs to shelter seats or resting benches.” [Fig. 8]

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.) [12] back up to history

- “PORCH, n. [Fr. porche, from L. porticus, from porta, a gate, entrance or passage, or from portus,a shelter.]

- “1. In architecture, a kind of vestibule supported by columns at the entrance of temples, halls, churches or other buildings. Encyc.

- Watterston, George, May 1844, “Landscape Gardening” (May 1844: 314) [13]

- “The fourth and last requisite in Landscape Gardening is the buildings. These should be so constructed as to be both attractive and useful objects. . . . A Gothic porch converted into a garden seat, or a window of rich workmanship, partly mantled over with ivy, might possess the merit of being a tasteful as well as a picturesque object.”

- Downing, A. J., 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849: 322, 375)[14]

- “In all its varieties the Honeysuckle is a charming plant, either to adorn the porch of the cottage, the latticed bower of the garden—to both of which spots they are especially dedicated—or to climb the stem of the old forest tree. . . .

- “A Porch strengthens or conveys expression of purpose, because, instead of leaving the entrance door bare, as in manufactories and buildings of an inferior description, it serves both as a note of preparation, and an effectual shelter and protection to the entrance. Besides this, it gives a dignity and importance to that entrance, pointing it out to the stranger as the place of approach. A fine country house, without a porch or covered shelter to the doorway of some description, is therefore as incomplete, to the correct eye, as a well printed book without a title page, leaving the stranger to plunge at once in medias res, without the friendly preparation of a single word of introduction. Porches are susceptible of every variety of form and decoration, from the embattled and buttressed portal of the Gothic castle, to the latticed arbor porch of the cottage, around which the festoons of luxuriant climbing plants cluster, giving an effect not less beautiful than the richly carved capitals of the classic portico.”

- Downing, A. J., February 1849, “On the Drapery of Cottages and Gardens” (Horticulturist 3: 354)[15]

- “A porch of rustic trellis-work was built over the front door-way, simple and pretty hoods upon brackets over the windows, the door-yard was all laid out afresh, the worn out apple trees were dug up, a nice bit of lawn made around the house, and pleasant groups of shrubbery, (mixed with two or three graceful elms,) planted about it. But, most of all, what fixes the attention, is the lovely profusion of flowering vines that enrich the old house; and transform what was a soulless habitation, into a home that captivates all eyes.”

- Downing, A. J., 1850, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850; repr., 1968: 147–48, 308) [16]

- “The open porch, of hewn timber, (either painted of a stone color, to harmonize with the outside walls, or stained and oiled, to show the grain of the wood) is a feature which we think one of the most important to the expression of this dwelling [Design XIII], both as regards beauty and comfort. Its size, and the seats on each side of it, point out its use—since it answers the purpose of a veranda, with much less cost. Covered by the grape vine, such a porch is at once a beautiful and a most agreeable feature to the eye of the passer by. It gives him, at a glance, the key-note to a refinement, quite compatible with a farmer’s life—a refinement not less real than that seen in another class of country houses or ornamental cottages—but simpler and less fanciful in its manifestation. . . .

- “The porch of this house [a Country-House in the pointed style], which projects 12 feet, breaks up (see elevation) the otherwise too long horizontal line of the veranda roof—and the novice will bear in mind, that as the spirit of the Gothic or pointed style lies in the prevalence of vertical or upward lines, so all long, unbroken, horizontal lines of roof should be avoided. [Fig. 9]

- “This porch, being pierced with arches on each side, opens on a continuous veranda, 10 feet wide and 80 feet long, which affords a fine promenade at all seasons—terminating on one side with the green-house—and there are few greater luxuries in a country-house in an American summer, such as it is in this latitude, than such a cool and airy veranda—especially if it looks out upon our fine river or lake scenery.*

- “*Any one living on the Hudson inevitably gets to look upon river scenery as an indispensible part of country landscape. This will account for the manner in which glimpses of river scenery creep into so many of these sketches of houses—often, as in this design, on the wrong side of the house.”

- Ranlett, William H., 1849, The Architect (1849; repr., 1976: 1:21) [17] back up to history

- “Verandas, piazzas and porches are very expressive of purpose, and a dwelling should always have one or more of them; and balconies, which are decidedly ornamental and not without use.”

Images

Inscribed

J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, “Porches and Porticoes,” in J. C. Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 356, fig. 330.

J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, “View from the Library Porch,” Cheshunt Cottage, in The Gardener’s Magazine 15, no. 117 (December 1839): 640, fig. 158.

John Notman, “No. 1 Ground Plan, Smithsonian Institute,” December 23, 1846. “Carriage porch” is inscribed below the “hall of entrance”; "porch” is inscribed below the “reception hall” on either side of the plan.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Kirri Cottage for Julia Jackson Davis, 1849.

(?) Forbes, “Cottage Villa of Wm. J. Rotch, Esq. New Beford, Mass.,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 4, no. 5 (November 1849): pl. opp. 201. “Front porch” is inscribed near the bottom of the plan; “back porch” is inscribed near the top of the plan.

Anonymous, “Design for a Country House,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 4, no. 6 (December 1849): pl. opp. 249.

Anonymous, “Principal Floor” of a Symmetrical Stone Farm House, in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. 145, fig. 59.

Anonymous, “A Country House in the Pointed Style,” in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. 304, figs. 133 and 134.

Associated

Anonymous, “Rustic Seat,” Montgomery Place, in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 2, no. 4 (October 1847): 157, fig. 26.

Frances Palmer, “English Cottage Style,” in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1849), vol. 1, pl. 27, design VIII. In an associated plate, Palmer provides detailed drawings of the “porch.”

Frances Palmer, “English Cottage Style,” in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1849), vol. 1, pl. 27, design IX. In an associated plate, Palmer provides detailed drawings of the “porch.”

Anonymous, “Rural Gothic Villa,” in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. 322, fig. 148. In the associated plan, the front entrance is labeled “Porch.”

Frances Palmer, “Waldwic Cottage,” in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), 2: 31. “Enclosed porch to the library.”

Attributed

Charles Fraser, A Seat on the Ashley River, April 1802.

William Russell Birch, “China Retreat Pennsyl.a the Seat of M.r Manigault,” 1808, in William Russell Birch and Emily Cooperman, The Country Seats of the United States (2009), 79, pl. 19.

Anonymous, “Villa of Theodore Lyman, Esq., near Boston,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 387, fig. 48.

Notes

- ↑ William Russell Birch, The Country Seats of the United States of North America: With Some Scenes Connected with Them (Springland, PA: W. Birch, 1808), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Pierson Jr. traces the origins of the feature, specifically found in Alexander Jackson Davis and A. J. Downing’s work, to the awning or canopy partaking of an oriental flavor. In general, its origin was a semi-enclosed outdoor space that was not at all architectural but was related to the ornamental canopy or tent. This connection might explain why the detail flourished during the high romantic period in American architecture. See Pierson, American Buildings and Their Architects: Technology and the Picturesque, the Corporate and the Early Gothic Styles, vol. 2 (New York: Doubleday, 1978), 300–4, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Jackson Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses; Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-Houses, and Villas (New York: D. Appleton, 1850; repr. New York: Da Capo, 1968), 357, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Jackson Downing, “A Visit to Montgomery Place,” The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 2, no. 4 (October 1847): 156, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pehr Kalm, The America of 1750: Peter Kalm’s Travels in North America. The English Version of 1770, 2 vols. (New York: Wilson-Erickson, 1937), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Flowers, “People and Plants: North Carolina’s Garden History Revisited,” Eighteenth Century Life 8, no. 2 (January 1983): 117–29, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Warner Barber and Henry Howe, Historical Collections of the State of New Jersey . . . with Geographical Descriptions of Every Township in the State, (Newark: Benjamin Olds, 1844), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constance Greiff, John Notman, Architect, 1810–1865 (Philadelphia: Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1979), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Watterston, “Landscape Gardening,” Southern Literary Messenger 10 (May 1844): 306–15, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening . . ., 4th ed. (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “On the Drapery of Cottages and Gardens,” The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 8 (February 1849): 353–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. (Andrew Jackson) Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses; Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-Houses, and Villas (New York: D. Appleton, 1850; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1968), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William H. Ranlett, The Architect, 2 vols. (1849–51; repr. New York: Da Capo, 1976), view on Zotero.