Bed

See also: Border, Flower garden, Nursery, Parterre

History

Definitions of bed, ranging from Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopaedia entry of 1741 to George William Johnson’s discussion of 1847, indicate that the word generally referred to, as the latter wrote, “the site on which any cultivated plants are grown.” As spaces for growing plants, beds were the basic building blocks of most kitchen and flower gardens, as well as parterres.

As seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century treatises and dictionaries explain, beds could be raised above the surface of the ground through the addition of extra soil or manure to distinguish them from surrounding walkways or turf and to allow better drainage and ease of maintenance. Edgings of organic or inorganic materials also helped to shore up the raised surface as well as to establish the bed’s outline.

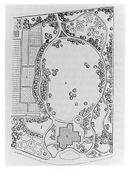

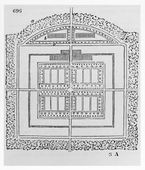

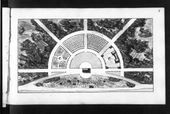

Treatise writers distinguished between different types of beds, each with a specific function, composition, and placement—such as hot bed, cold bed, kitchen bed, nursery bed, or flower bed. [1] The form and techniques of making specialized utilitarian beds, such as hot beds, changed little over the centuries. Oblong and rectangular forms were favored for utilitarian beds because such shapes allowed easy maintenance— especially when intersected by walkways. They were well suited to the general practice of subdividing kitchen gardens into squares or rectangles [Fig. 1]. In contrast, the shape and arrangement of ornamental flower beds changed dramatically between 1700 and 1850 [Fig. 2].

At the end of the eighteenth century, treatise writers such as Charles Marshall and Bernard M’Mahon dismissed the ancient style of flower gardens and its predilection for beds shaped in imitation of scroll work or embroidery. They advocated oblong or square beds framed with boards and separated by walks or alleys. David Huebner’s watercolor of 1818, House with Six-Bed Garden, is a stylized representation of the rectangular form of bed described by these two authors [Fig. 3].

In addition to specifying the form of beds, M’Mahon (1806) also provided specific instructions for the arrangement of flowers within beds, separating bulbous from herbaceous plants for ease of maintenance. (This tradition of separating flowers into individual beds can be traced back to at least the eighteenth century, when British florists advocated such planting practices.) M’Mahon did, however, allow for mixing species in order to ensure continuous blooms. Evidence indicates that separating plant types by bed was practiced in nineteenth-century America, as at Monticello.

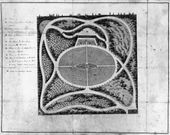

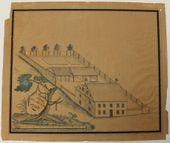

During the second half of the eighteenth century, another pronounced shift in flower bed design developed in England, from geometric rectilinear beds to circular or irregular oval (or kidney-shaped) beds. The latter beds were sometimes planted in concentric circles with plants arranged according to height, from lowest at the edges to highest at the center of the bed. [2] These practices, adopted in America, are well documented at Jefferson’s plantation, which vividly illustrates the growing preference for oval or curved beds. Jefferson originally proposed rectangular beds to be encompassed by twin pavilions [Fig. 4], but eventually he built oval beds [Fig. 5]. This oval shape was repeated in the beds located along the serpentine walk extending from the pavilion arms. While it is not known how the plants were arranged within these outlying beds, Jefferson noted that oval beds permitted him a greater variety of flowers, as compared to his strict arrangement by species in the beds nearest the house. Monticello also demonstrates how beds might be interspersed throughout the grounds, particularly along walkways, underneath windows, or outside doorways.

The accounts of treatise writers and observers of the American landscape confirm that circular or oval beds became the fashion in the first half of the nineteenth century [Fig. 6]. In the May 1835 issue of Horticultural Register, James E. Teschemacher proposed situating oval beds, filled with herbaceous flowers arranged in graduated rows, in front of the house. Like Jefferson, Teschemacher also envisioned punctuating walks with beds tucked along the curves of the walk and set into the turfed lawn. In 1840, C. M. Hovey declared that circular beds set in the front lawn was the new mode, an observation attested to by such sites as the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., and the Hudson River estates of Montgomery Place and Highland Place.

While the pseudonymous Londoniensis, writing in October 1850 in the Magazine of Horticulture, insisted that circular beds were universally adopted in the United States, alternate forms of bed designs also proliferated. The Magazine of Horticulture, in February 1840, for example, proposed that beds be arranged in knot patterns for a flower garden featuring annuals; it also described A. J. Downing’s employment of “arabesque” beds set into the lawn of his garden, as well as circular and irregular oval-shaped beds.

In his 1849 treatise on landscape gardening, Downing provided a cogent explanation for the proliferation of different forms of bed designs at mid-century. He argued that different styles of gardens required different forms of beds. The architectural garden employed beds in the shape of circles, octagons, and squares, set off by edgings of permanent or semi-permanent material; the irregular garden featured beds “varied in outline” cut into the turf; the French garden relied on beds executed in “embroidery” designs and separated by grass or gravel walks; and the English flower garden utilized patterned beds of “irregular curved designs” (also known as arabesques) cut into the turf. Each corresponding style of garden and bed required different types of plants; for example, the French or embroidery garden employed “low-growing” herbaceous plants that allowed the design to be rendered distinctly. Moreover, each style was suited for a particular location. For example, the irregular garden was ideal for picturesque or rustic settings distant from the house, while the architectural garden was intended to be placed near the house, where it could be viewed from the windows.

Closely related to the issue of the shape of beds was that of how the feature might be edged. Treatise writers, from around 1700 to 1850, debated repeatedly whether beds should be edged with semi-permanent materials, such as boards and tile, or living materials, such as boxwood (see Edging). In general, the aim was to achieve the appearance of neatness, no matter what the shape, style, or planting arrangement of the bed. While questions of form, technique, and style of beds preoccupied the design profession, the social significance of flower beds was also considered. At least two treatise writers, Teschemacher (1835) and Walter Elder (1849), explicitly linked flower beds to women. Teschemacher recommended that women, probably from middle or upper classes, should supervise the arrangement of plants by color because of their presumed training in domestic arts and decoration. Elder, however, suggested that women were best suited to the task of weeding flower beds, similarly linking femininity and domestic order.

-- Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Grigg, William, 4 October 1736, describing the residence of Thomas Hancock on Beacon Hill, Boston, Mass. (quoted in Lockwood 1931: 1:32) [3]

- “I the Subscriber oblidge myself for Consideration of forty pounds to be well & truly paid me by Thos. Hancock Doe undertake to layout the upper garden allys. Trim the Beds & fill up all the allies with such Stuff as Sd Hancock shall order. . . .”

- Gardener, John Little, 1742, describing items in a garden in Boston, Mass. (Massachusetts Archives, Suffolk County Probate Records, 76456)

12 Frames for hot Beds @30 10 = = 1 basket fo old Iron w.g. 82lb @6d 2 = 1 = 36 Frames with Glass for the hot Beds 20/ 36 = =

- Lamboll, Thomas, 16 February 1761, describing his wife’s garden in Charleston, S.C. (quoted in Pinckney 1969: 12) [4]

- “In Cold Weather she causes the Flower-Beds to be Covered and Sheltered, especially when they have begun to Sprout.”

- Drowne, Samuel, 24 June 1767, describing Redwood Farm, seat of Abraham Redwood Jr., Portsmouth, R.I. (Rhode Island Landscape Survey)

- “Mr. Redwood’s garden . . . is one of the finest gardens I ever saw in my life. In it grows all sorts of West Indian fruits, viz: Oranges, Lemons, Limes, Pineapples, and Tamarinds and other sorts. It has also West Indian flowers—very pretty ones—and a fine summer house. It was told my father that the man that took care of the garden had above 100 dollars per annum. It had Hot Houses where things that are tender are put for the winter, and hot beds for the West India Fruit. I saw one or two of these gardens in coming from the beach.”

- Logan, Martha, 1768, describing in the South Carolina Gazette a sale in Charleston, S.C. (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 30) [5]

- Cutler, Rev. Manasseh, 14 July 1787, describing Gray’s Tavern, Philadelphia, Pa. (1987: 1:276) [6]

- “We at length came to a considerable eminence, which was adorned with an infinite variety of beds of flowers and artificial groves of flowering shrubs.”

- Cutler, Rev. Manasseh, 17 July 1787, describing gardens of François André Michaux, Bergen, N.J. (1987: 1:291) [6]

- “They, however, showed me the Gardens, and were very complaisant. There were a considerable collection of exotic shrubs and plants, set in a kind of beds for transplanting.”

- Hamilton, William, 1789?, in a letter to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith, discussing plans for the Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Madsen 1988: A4) [7]

- “I desire George when he is about it [digging a border] will put the Ranunculus roots in the same Bed in the same manner [planted at six or eight Inches from each other & about 5 or 6 inches deep].”

- Bentley, William, 22 October 1790, describing Elias Hasket Derby Farm, Peabody, Mass. (1962: 1:180, 373) [8]

- “The Strawberry beds are in the upper garden, & the whole divisions are not according to the plants they contain. The unnatural opening of the Branches of the trees is attempted with very bad effect. . . .

- “By invitation from Mr Derby the Clergy spent this afternoon at the Farm in Danvers. We were regaled at our arrival, after the best liquors at the house, with a feast in his Strawberry beds. They were in excellent order, & great abundance. He measured a berry, which was 2 inches 1/2 in circumference.”

- Ogden, John Cosens, 1800, describing Bethlehem, Pa. (p. 14) [9]

- “In the rear of this [girl’s school], is another small enclosure, which forms a broad grass walk and is skirted on each side by beds devoted to flowers, which the girls cultivate, as their own.”

- Drayton, Charles, 2 November 1806, describing the Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, Pa. (Drayton Hall, Charles Drayton Diaries, 1784–1820, typescript)

- “The Hot houses, they may extend in front I suppose 40 feet each. they have a wall heated by flues—& 3 glazed walls & a glazed roof each. in the centre, a frame of wood is raised about 2 1/2 feet high, & occupying the whole area except leaving a passage along by the walls. in the flue wall or adjoining, is a cistern for tropic aquatic plants. within the frame, is composed a hot bed; into which the pots & tubs with plants are plunged. This Conservatory is said to be equal to any in Europe. It contains between 7 & 8000 plants. To this the Professor of botany is permitted to resort, with his Pupils occasionally.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, 7 June 1807, in a letter to his granddaughter, Anne Cary Randolph, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, Va. (quoted in Betts and Perkins 1986: 36) [10]

- "I find that the limited number of our flower beds will too much restrain the variety of flowers in which we might wish to indulge, and therefore I have resumed an idea . . . of a winding walk surrounding the lawn . . . with a narrow border of flowers on each side. . . . I enclose you a sketch of my idea, where the dotted lines on each side. . .shew the border on each side of the walk. The hollows of the walk would give room for oval beds of flowering shrubs." [Fig. 7]

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1 November 1813, describing Poplar Forest, property of Thomas Jefferson, Bedford County, Va. (quoted in Chambers 1993: 105) [11]

- “[Planted] large roses of difft. kinds in the oval bed in the N. front. dwarf roses in the N.E. oval. Robinia hispida in the N. W. do. Althaeas, Gelder roses, lilacs, calycanthus, in both mounds.”

- Trollope, Frances Milton, 1828, describing Cincinnati, Ohio (1832: 1:87) [12]

- “The water-melons, which in that warm climate furnish a delightful refreshment, were abundant and cheap; but all other melons very inferior to those of France, or even of England, when ripened in a common hot-bed.”

- Anonymous, 3 October 1828, “Parmentier’s Horticultural Garden,” describing André Parmentier’s horticultural and botanical garden, Brooklyn, N.Y. (New England Farmer 7: 84)

- “The beds of the flowering or ornamental part compose broad belts laid out in a serpentine or waving direction, and edged with thrift, (statice armeria).”

- Dearborn, H.A.S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Mass. (quoted in Ward 1831: 48) [13]

- “The nurseries may be established, the departments for culinary vegetables, fruit, and ornamental trees, shrubs and flowers, laid out and planted, a green house built, hot-beds formed”

- Driver, George, 1838, describing his garden in Salem, Mass. (Peabody Essex Institute Phillips Library, Diaries of George Driver, mss 200, box 1, folder 1)

- “[6 March] Put the Glass on my hot bed....“[25 March] Hot Bed in fine order this morning finished fitting it up this morning and planted radishes, lattic, york cabbage and cucumber at noon. have put in about 12 inches of manure and 8 or 9 of loom appear to be in fine order. . . .

- “[30 March] Have lost most of the under heat in my hot beds on account of storm the rain not having shower for three day and very cold. still they are in very good order today, have planted cucumber, Mellon, Cabbage, lattic, pepper grass, and radish seed.”

- Hovey, C. M., October 1839, “Some Remarks upon several Gardens and Nurseries in Providence, Burlington, (N.J.) and Baltimore,” describing the residence of Charles Phelps, Esq., Stonington, Conn. (Magazine of Horticulture 5: 362) [14]

- “The flower garden contains about a quarter of an acre, in front of the house, and between that and the road, and is walled in on the north and west side. It is tastefully laid out in small beds, edged with box; on the north side stands a moderately sized green-house, about forty feet long.”

- Buckingham, James Silk, April 1840, describing the garden of Father George Rapp, Economy, Pa. (1842: 227) [15]

- “This [the garden] covered about an acre and half of ground, and was neatly laid out in lawns, arbours, and flower-beds, with two prettily ornamented open octagonal arcades, each supporting a circular dome over a fountain.”

- Hovey, C. M., November 1841, “Select Villa Residences,” describing Highland Place, estate of A. J. Downing, Newburgh, N.Y. (Magazine of Horticulture 7: 403, 406, 409) [16]

- “4. Arabesque beds on the lawn, for choice flowers, such as roses, geraniums, fuchsias, Sálvia pàtens, fúlgens, and cardinàlis, &c., to be turned out of pots in the summer season, after being wintered in green-houses or frames. Such beds should be sparingly introduced, or they would give the lawn a frittered appearance by cutting it up to an extent which would destroy its breadth, which constitutes its greatest beauty. It is even considered by some landscape writers, rather an error to introduce any forms but the circle, unless the beds are looked down upon from an elevated terrace, when these arabesque shapes will have a pretty appearance.

- “5. Circular beds for petunias, verbenas, which now form one of the principal ornaments of the garden, Phlóx Drummóndii, nemophilas, nolanas, dwarf morning-glory, &c. ...

- “18. Flower garden, in front of the greenhouse. It is laid out in circular beds, edged with box, with gravel walks. . . .

- “the flower garden (18,) a small space laid out with seven circular beds; the centre one nearly twice as large as the outer ones: these were all filled with plants: a running rose in the centre of the large bed, and the outer edge planted with fine phloxes, Bourbon roses, &c.: the other six beds were all filled with similar plants, excepting the running rose, which would be of too vigorous growth for their smaller size. Under the arborvitae hedge here, on the south side of the garden, the green-house plants were arranged in rows, the tallest at the back.” [Fig. 8]

- Hovey, C. M., April 1842, “Notes made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, &c.,” describing the U.S. Capitol, Washington, D.C. (Magazine of Horticulture 8: 127) [17]

- “From this lower terrace, a long flight of steps leads to the upper one, upon which the building of the Capitol is placed: on the turf between the walks, are oval and circular beds, planted with shrubs and roses, and filled with dahlias and other annual flowers.”

- Moore, Mary Clara, 26 April 1843, in a letter to Frances Magill, describing Shadows-on-the-Teche, New Iberia, La. (quoted in Turner 1993: 493–94) [18]

- “Please make Martha sow some more mustard in the Garden for Greens and plant some of those black-eyed Peas...that the Negroes may have something to boil with...she can put some of them in the bed where I planted artichokes and many other places in the meantime.”

- Hovey, C. M., July 1846, “Notes of a Visit to several Gardens in the Vicinity of Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York,” describing the garden of W. H. Corcoran, Washington, D.C. (Magazine of Horticulture 12: 245) [19]

- “Four of the beds on the turf were edged with basket work, and had the appearance of being filled with a profusion of flowers.”

- Downing, A. J., October 1847, describing Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, N.Y. (quoted in Haley 1988: 52) [20]

- “THE FLOWER GARDEN.

- “How different a scene from the deep sequestered shadows of the Wilderness! Here all is gay and smiling. Bright parterres of brilliant flowers bask in the full daylight, and rich masses of colour seem to revel in the sunshine. The walks are fancifully laid out, so as to form a tasteful whole; the beds are surrounded by low edgings of turf or box, and the whole looks like some rich oriental pattern of carpet or embroidery.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., April 1848, describing pleasure grounds and farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, Pa. (Journal of Insanity 4: 348) [21]

- “East of the entrance is the private yard and residence of the Physician of the Institution, being the mansion house on the farm when purchased by the Hospital. The vegetable garden containing three and a half acres is next, and in it are the green-house, hot-beds, seed-houses, &c.”

- Londoniensis [pseud.], October 1850, “Notes and Recollections of a Visit to the Nurseries of Messrs. Hovey & Co., Cambridge” (Magazine of Horticulture 16: 443)

- “This lawn is encircled by a broad walk, on the lawn side of which are circular beds of the choicest summer blooming plants. I did not much like this multitude of circular beds, but it is the general style throughout the country.”

- Dufield, Elizabeth Lewis, 14 May 1851, describing the Hermitage, estate of Andrew Jackson, Nashville, Tenn. (Ladies Hermitage Association Research #977)

- “The garden in which the monument is erected is beautifully laid on with flower and fruits. There is a small circle in the middle which is one solid bed of verbena, pinks, tulips, pinys and other flowers too tedious to mention and too beautiful for me to attempt a description.”

- Jackson, Sarah Y., 10 April 1852, describing the Hermitage, estate of Andrew Jackson, Nashville, Tenn. (Hermitage Collections, Andrew Jackson Papers, G-13-1)

- “We are making some few improvements in it this season, bricking round the beds, and have had a supply of fine roses. We have now about fifty varieties of roses, some very fine.”

- Logan, Deborah Norris, 1867, describing the garden of Charles Norris, Philadelphia, Pa. (p. 6) [22]

- “It was laid out in square parterres and beds, regularly intersected by graveled and grass walks and alleys.”

Citations

- Worlidge, John, 1669, Systema Agriculturae (p. 147) [23]

- “To make a hot Bed in February, or earlier if you please, for the raising of Melons, Cucumbers, Radishes, Coleflowers, or any other tender Plants or Flowers, you must provide a warm place defended from all Windes, by being inclosed with a Pale, or Hedge made of Reed or Straw, about six or seven foot high . . . within which you must raise a Bed of about two or three foot high, and three foot over, of new Horse-dung . . . edged round with boards, lay of fine, rich mould about three or four inches thick, and when the extream heat of the Bed is over . . . than plant your Seeds.”

- La Quintinie, Jean de, 1693, “Dictionary,” The Compleat Gardener ([1693] 1982: n.p.) [24]

- “Beds are plots of dressed Ground, which in digging, are wrought into such a form by the Gard’ner, as is most convenient to the temper and situation of the Earth in that place, and to the nature of the Plants to be sown or planted in it. They are of two sorts, Cold and Hot.

- “Cold Beds are made either of Natural Earth, or mixed and improved Mold, and are in moist Grounds raised higher than the Paths, to keep them moderately dry, and in rising and dry Grounds, laid lower than the Paths, that they may on the contrary retain moisture so much the better, and profit so much the more by the Rain that falls.

- “Hot Beds, are Beds composed of Long New Dung, well packt together, to such a height and breadth as is prescribed in the Body of the Book, and then covered over to a certain thickness, with a well tempered Mold, in order to the planting or sowing such plants in them, as are capable of being by Art, forced to grow, and arrive to maturity even in the midst of Winter, or at least a considerable while before their natural Season.

- “How these Beds are differently made for Mushrooms, and how for other Plants, See in the work itself.

- “Deaf Beds are such Hot Beds as are made hollow in the Ground, by taking away the natural Earth to such a certain depth, and filling the place with Dung, and then covering it with Mold, till it rise just even with the Surface of the Ground. They are used for Mushrooms.

- “Kernel Beds are Nursery Beds, wherein the Seed or Kernels of Kernel Fruit are sown in order to raise Stocks to Graff upon.”

- Bradley, Richard, 1728, Dictionarium Botanicum (2:n.p.) [25]

- “It is an Error to lay the Flower-Beds in Parterre Works high in the Middle, or round, as the Gardeners call it; I would rather advise that such Beds be made concave, so as lie hollow in the Middle; for as these shou’d chiefly be furnish’d with annual Flowers in the Summer, and the most fiberous Rooted Plants, and perhaps Ever-greens, likewise, by this Means the wateuring they may require in the scorching Seasons, will be effectual to them. . . . There is indeed some Beauty in the roundness of a Bed, and that Roundness is necessary, when we design a Bed only for our finest bulbous Roots, because their chiefest Growing-time is in the moister Seasons of the Year.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, Cyclopaedia (1:n.p.) [26]

- “[vol. 1] BED, in gardening, a piece of made-ground, raised above the level of the adjoining ground, usually square or oblong, and enriched with dung or other amendments; intended for the raising of herbs, flowers, seeds, roots, or the like.

- “Hot-BED. See the article HOT-Bed....

- “HOT-BED, a piece of earth or soil plentifull enriched with manure, and defended from cold winds, &c. to forward the growth of plants, and force vegetation, when the season or the climate of itself is not warm enough. . . .

- “[vol. 2] PARTERRE, in gardening, that open part of a garden into which we enter, coming out of the house; usually, set with flowers, or divided into beds, encompassed with platbands, &c. See GARDEN. ...

- “PLAT-BAND, in gardening, a border, or bed of flowers, along a wall, or the side of a parterre; frequently edged with box, &c. See PARTERRE, EDGING, &c.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1:n.p.) [27]

- “BED. n.s. [beb, Sax.] . . .

- “4. Bank of earth raised in a garden. . . .

- “HO’TBED. n.s. A bed of earth made hot by the fermentation of dung.”

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.) [28]

- “bank of earth raised in a garden . . . the place where any thing is generated; a layer, a stratum.”

- Anonymous, 1798, Encyclopaedia (8:682) [29]

- “HOT-BEDS, in gardening, beds made with fresh horse-dung, or tanner’s bark, and covered with glasses to defend them from cold winds.

- “By the skilful management of hot-beds, we may imitate the temperature of warmer climates; by which means, the seeds of plants brought from any of the countries within the torrid zone may be made to flourish even under the poles.

- “The hot-beds commonly used in kitchen-gardens, are made with new horse dung.”

- Marshall, Charles, 1799, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening (1:42–43) [30]

- “The flower garden (properly so called) should be rather small than large; and if a portion of ground be separately appropriated for this, only the choicest gifts of Flora should be introduced, and no trouble spared to cultivate them in the best manner. The beds of this garden should be narrow, and consequently the walks numerous; and not more than one half or two thirds the width of the beds, except one principal walk all round, which may be a little wider. . ..

- “Figured parterres in scrolls, flourishes, &c, have got out of fashion, as a taste for open and extensive gardening has prevailed; but when the beds are regular in their shapes, and chiefly at right angles, (after the Chinese manner) an assemblage of all sorts of flowers, in a fancy spot of about sixty feet square, is a delightful home source of pleasure, that still deserves to be countenanced. There should be neat edgings of box to these beds, or rather of boards, to keep up the mould.”

- Gardiner, John, and David Hepburn, 1804, The American Gardener (p. 107) [31]

- “CROCUSES, RANACULUSES, ANEMONES AND OTHER BULBS.

- “These flowers may be planted this month [January] (when the weather is mild) in beds and borders of dry light earth well dug and broke.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (pp. 66, 71–72) [32]

- “These [[[parterres]]] were bounded by a long bed, or border of earth, and the internal space within, divided into various little partitions, or inclosures, artfully disposed into different figures, corresponding with one another, such as long squares, triangles, circles, various scroll-works, flourishes of embroidery, and many other fanciful devices; all of which figures, were edged with dwarf-box, &c. with intervening alleys of turf, fine sand, shells, &c.

- “The partitions or beds were planted with the choicest kinds of flowers; but no large plants, to hide the different figures, for such, were intended as a decoration for the whole place, long after the season of the flowers was past. . . .

- “The form of this [[[flower-garden]]] ground may be either square, oblong, or somewhat circular; having the boundary embellished with a collection of the most curious flowering-shrubs; the interior part should be divided into many narrow beds, either oblong, or in the manner of a parterre; but plain four feet wide beds arranged parallel, having two feet wide alleys between bed and bed, will be found most convenient, yet to some not the most fanciful.

- “In either method, a walk should be carried round the outward boundary, leaving a border to surround the whole ground, and within this, to have the various divisions or beds, raising them generally in a gently rounding manner, edging such as you like with dwarf-box, some with thrift, pinks, sisyrinchium, &c. by way of variety, laying the walks and alleys with the finest gravel. Some beds may be neatly edged with boards, especially such as are intended for the finer sorts of bulbs, &c.

- “In this division you may plant the finest hyacinths, tulips, polyanthus-narcissus, double jonquils, anemones, ranunculus’s, bulbous-iris’s, tuberoses, scarlet and yellow amaryllis’s, colchicums, fritillaries, crown-imperials, snowdrops, crocus’s, lilies of various sorts, and all the different kinds of bulbous, and tuberous-rooted flowers, which succeed in the open ground; each sort principally in separate beds, especially the more choice kinds, being necessary both for distinction sake and for the convenience of giving, such as need it, protection from inclement weather; but for particulars of their culture, see the respective articles in the various months.

- “Likewise in this division should be planted a curious collection of carnations, pinks, polyanthus’s, and many other beautiful sorts, arranging some of the most valuable in beds separately; others may be intermixed in different beds, forming an assemblage of various sorts.

- “In other beds, you may exhibit a variety of all sorts, both bulbous, tuberous, and fibrous rooted kinds, to keep up a succession of bloom in the same beds during the whole season.”

- Thorburn, Grant, 1817, The Gentleman & Gardener’s Kalendar (pp. 5–6) [33]

- “[January] FORMATION OF HOT-BEDS.

- “Take fresh horse-dung with plenty of long litter in it; shake the dung well and place it on a piece of ground the size of the bed you want to make; the first layer or two should have more litter than the others;—beat the dung well down with your fork as you proceed with the layers, till your bed is the height you want it. Different vegetables require beds of different heights—but the mode of making them is the same. The bed being thus made, place a frame light over it’ and in six or eight days the bed will be in strong fermentation.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.) [34]

- “BED, n. [Sax. bed; D. bed; G. bett or beet; Goth. badi. The sense is a lay or spread, from laying or setting.] ...

- “4. A plat or level piece of ground in a garden, usually a little raised above the adjoining ground. Bacon.”

- Prince, William, 1828, A Short Treatise on Horticulture (pp. 87, 155) [35]

- “Dwarf Box.— This is the low growing variety, generally used for edging of garden walks and flower beds. Its growth is slow, but at very advanced age it attains to a shrub of from six to eight feet high. It is this variety which is so widely spread and well known throughout the country. . . .

- “DIRECTIONS for the Culture of Bulbous and Tuberous Flower Roots.

- “The beds should be raised from four to six inches above the level of the walks, and moderately arched, which will give an opportunity for all superfluous moisture to run off; some sand strewed in the trenches, both before and after placing the roots, would be of advantage.”

- Bridgeman, Thomas, 1832, The Young Gardener’s Assistant (pp. 110–11) [36]

- “Generally speaking, a Flower Garden should not be upon a large scale; the beds or borders should in no part of them be broader than the cultivater can reach to, without treading on them: the shape and number of the beds must be determined by the size of the ground, and the taste of the person laying out the garden. Much of the beauty of a pleasure garden depends on the manner in which it is laid out; a great variety of figures may be indulged in for the Flower bed. Some choose oval or circular forms, others squares, triangles, hearts, diamonds, &c., and intersected winding gravel walks.”

- Fessenden, Thomas, 1833, The New American Gardener (pp. 109–10) [37]

- “Sowing and planting....The beds should be raised three or four inches above the level of the walks.”

- Teschemacher, James E., 1 May 1835, “On Horticultural Architecture” (Horticultural Register 1: 159–60)

- “The three oval beds may be used for flowers in masses; for instance, that in the centre for varieties of roses planted at sufficient distance to enable a mixture of the monthly and sanguinea species which have been protected during the winter, thus maintaining a succession. . . . On the right, opposite to the principal chamber window, are three curved beds, each four and a half feet wide, edged with box and divided by narrow walks three or three and half feet in width, for the purpose of permitting examination, intended for choice herbaceous flowers; observing that the tall growing species, as dahlia, lofty delphinium, &c. should be placed in the bed most distant from the house, and those of the lowest growth in front. Here may be a fine collection of Paeonia, Iris, Trigidia, Lychnis fulgens and chalcedonica, Phloxes, particularly the white, Ornothera, Pentstemon, Lilum flavum, Gentians, with any others; it will add much to their charm if the colors are so blended as to harmonize well; for instance, by bringing the blues and yellows or whites and scarlets into immediate contrast, as may be observed in many striped flowers; those who wish to imbibe true principles of taste will achieve more by observing and studying forms and arrangements of colors presented by nature, than by any artificial rules that can be offered; this department however may safely be entrusted to the superintendence of the ladies, who naturally possess a finer tact in these matters, and to whom it will prove a constant fund of amusement. In the original formation of these beds great attention should be paid not to have the plants too near each other, for then confusion ensues and it is almost impossible to keep them neat, on which much of their effect depends.” [Fig. 9]

- Teschemacher, James E., 1 June 1835, “On Horticultural Architecture” (Horticultural Register 1: 229) [38]

- “The separate beds for distinct flowers may be formed behind the turnings of the walk so as to come upon them unexpectedly; for instance, at a bend the eye may fall suddenly on a bed eight or ten feet long of scarlet turban Ranunculus, and from thence pass on to others containing mixed Ranunculus and mixed Anemone,—one for tulips, another for pinks, a bed of peat filled with Gentiana acaulis—if the experiment making this year prove it able to be cultivated here—makes a most magnificent shew.”

- Sayers, Edward, 1838, The American Flower Garden Companion (p. 15) [39]

- “The beds [of a flower garden] should also be well proportioned, and not too much cut up into small figures, which when bordered with box edging, have the appearance of so many figures formed for the amusement of children more than for the purpose of growing flowers.”

- W., M. A., February 1840, “On Flower Beds” (Magazine of Horticulture 6: 51–52)

- “The laying out of a flower knot, or system of beds in a flower garden, is one of the first feats in which the young gardener undertakes to show off his abilities; and being one which affords the most ample scope for the play of fancy, is therefore, perhaps, the one in which he is most likely to manifest the display of a bad taste. Even where the design is of the most happy conception, and the plotting beautiful upon paper, the difficulty of defining and preserving accurately the outline of the figure, when practically applied, will often quite destroy the anticipated pleasing effect. Edge-boards of wood, so thin as to be easily bent to the required form, are commonly the first material employed. These soon warped out of shape, or quickly rot, and impart a deleterious principle to the soil in contact with them; and a very common fault is to have them too wide, so that the plants in the beds suffer from drought, while the paths between them resemble gutters more than walks for pleasure.

- “Bricks, or tiles moulded expressly for the purpose, are next resorted to, and if sunk so that the earth in the beds shall not be more than from one to two inches above the level of the paths, they serve pretty well for some time. But so soon as they begin to crumble from the influence of frost, or are covered with green mould or moss, as they soon will be in moist or shady exposures, they become offensive to the eye, though not, like the first, injurious to the soil. A living margin, therefore, becomes the next and last expedient; and indeed it may be regarded as one of the last steps in the march of horticultural refinement. To adapt such a line of vegetation to the size and form of the bed, and make it harmonize in every point of reference with the group of plants within, requires a cultivated delicacy of perception, a sound judgement, and an accurate knowledge of all the principles of natural and gardenesque beauty, as well as of the characters of the plants or materials which are necessary, with a due arrangement, to produce it.

- “It is probably as difficult to fix upon the most suitable plant for the edging of a flower bed, as it is to determine the best shrub for a hedge around fields. For the borders of main avenues, or broad walks in grounds of considerable extent, box, as recommended, Vol. V., p. 350, is undoubtedly the best; but for small parterres, or the flower beds in a front door yard, it seems much less suitable. They can commonly be taken in at one glance of the eye, and notwithstanding all that has been said of the artificial or geometric style, it is the proper one for such places; for symmetry, or a perfect balance of corresponding parts, greatly strengthens the impression of such a scene, taken as a whole, or single mass of objects. The beds, therefore, will not only be small, but when there is the proper variety in the form of them, some, at least, must have quite acute angles.”

- Hovey, C. M., March 1840, “Some Remarks on the Formation of the Margins of Flower Beds on Grass Plots or Lawns” (Magazine of Horticulture 6: 84–85)

- “We are glad to learn that our observations have been the means of drawing attention to the subject, and that they have, in some instances, induced amateurs to adopt the style of planting small grass plots, and forming upon them circular, or other shaped beds, for flowers. In front gardens to small suburban villas, nothing can be prettier than this plan of occupying the ground, and the method is, generally, to be much preferred to the old, and almost universally followed system, of forming gravelled walks, with board, grass, or box edgings, and dug borders. This is particularly so, when the object is to have a neat garden, and kept in order at the least expense.”

- Anonymous, May 1840, “On the Cultivation of Annual Flowers” (Magazine of Horticulture 6: 186–88)

- “In the two plans annexed, we have supposed the flower garden to be situated directly in front of the green-house and to be just the same length, (thirty-two feet, the ordinary length of a common sized house,) and width; the beds should be laid out with care, as on their precision much of their beauty depends: the beds may be surrounded with box edging, and gravel walks between, or they may be edged with what we have found to answer a good purpose, Iceland moss. This forms a perpetual green, and, if kept neatly trimmed, is full as desirable an edging around such common beds as the box: supposing this to be all completed, we next come to the planting of the beds. This, as we have just observed, may be devoted wholly to annuals, to annuals and perennials, and to both, with the addition of tender plants, such as verbenas, &c. &c.; but we shall at present speak of them as only to be filled with annuals. . . .

- “The first plan . . . may be planted as follows: In the centre circular bed may be planted marigolds, Marvel of Peru, tall branching larkspurs, and German asters, placing the tallest in the centre; or a dahlia or two may be planted in the same place, and on the outer edge a few dwarf plants may be planted; the eight small beds next to this may be planted with a miscellaneous collection of sorts, growing from a foot to two feet high, placing the dwarfest at the outer edge of the bed; the four larger beds next, may be also planted with miscellaneous kinds, growing about a foot high; and the four corner beds may be planted with very dwarf or trailing sorts, such as the nemophilas, nolanas, Lobèlia grácilis, Clintònia pulehélla and élegans, Chrysèis cròcea, Silène multiflòra, pansies, &c. [Fig. 10]

- “The second plan . . . admits of a greater display of plants, and, in particular, when it is desirable to have them in masses of one color, viz: the centre may be wholly planted with the finest double German asters in mixed colors: two of the four oval beds, those opposite each other, may be planted with Clárkia élegans, C. élegans ròsea, and C. pulchélla, placing the latter at the outer edge; and the other, two with rocket larkspurs in mixed colors, to be succeeded with German astors, brought forward and reserved for the purpose. Two of the four large beds between the oval ones may be planted with Chrysèis cròcea and califórnica mixed, and the other two with crimson and white petunias mixed together: the four small beds may be filled with Lobèlia grácilis, Clintònia élegans, Nemóphila insígnis, and Nolàna atriplicifòlia, each kind in separate bed, and the two latter opposite to each other.” [Fig. 11]

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (pp. 84, 165, 304–8) [40]

- “BED is a comprehensive word, applicable to the site on which any cultivated plants are grown. It is most correctly confined to narrow divisions, purposely restricted in breadth for the convenience of hand weeding or other requisite culture. . . .

- “CONSERVATORY. This structure is a greenhouse communicating with the residence, having borders and beds in which to grow its tenant plants. . . .

- “HOT-BED. When a temperature of 45°, moisture, and atmospheric air occur to deaden vegetable matters, these absorb large quantities of oxygen, evolving also an equal volume of carbonic acid. As in all other instances where vegetable substances absorb oxygen gas in large quantities, much heat is evolved by them when putrefying; and advantage is taken of this by employing leaves, stable-litter, and tan, as sources of heat, or hot-beds, in the gardener’s forcing department.

- “A hot-bed is usually made of stable-dung. . . .

- “In making the beds, they must be so situated as to be entirely free from the overshadowing of trees, buildings, &c., and having an aspect rather a point eastward of the south. A reed fence surrounding them on all sides is a shelter that prevents any reverberation of the wind, an evil which is caused by paling or other solid inclosure. This must be ten feet high to the northward or back part, of a similar height at the side, but in front only six. . . . An inclosure of this description, one hundred feet in length and sixty broad, will be of a size sufficiently large for the pursuit of every description of hot-bed forcing.

- “To prevent unnecessary labour, this inclosure should be formed as near to the stable as possible. . . .

- “The breadth of a bed must always be five feet. . . .

- “The roots of plants being liable to injury from an excessive heat in the bed, several plans have been devised to prevent this effect. If the plants in pots are plunged in the earth of the bed, they may be raised an inch or two from the bottom of the holes they are inserted in by means of a stone. But a still more effectual mode is to place them within other pots, rather larger than themselves.”

- Downing, A. J., April 1847, “Hints on Flower Gardens” (Horticulturist 1: 443–44)

- “our own taste leads us to prefer the modern English style of laying out flower gardens upon a ground work of grass or turf, kept scrupulously short. Its advantage over a flower garden composed only of beds with a narrow edging and gravel walks, consists in the greater softness, freshness and verdure of the green turf, which serves as a setting to the flower beds, and heightens the brilliancy of the flowers themselves. Still, both these modes have their merits, and each is best adapted to certain situations, and harmonizes best with its appropriate scenery. . ..

- “One of these [defects] is the common practice, brought over here by gardeners from England, of forming raised convex beds for flowering plants. This is a very unmeaning and injurious practice in this country, as a moment’s reference to the philosophy of the thing will convince any one. In a damp climate, like that of England, a bed with a high convex surface . . . by throwing off the superfluous water, keeps the plants from suffering by excess of wet, and the form is an excellent one. In this country, where most frequently our flower gardens fail from drouth, what sound reason can be given for forming the beds with a raised and rounded surface of six inches in every three feet, so as to throw off four-fifths of every shower? The true mode, as a little reflection and experience will convince any one, is to form the surface of the bed nearly level . . . so that it may retain its due proportion of all the rains that fall.”

- Elliott, Charles Wyllys, October 1848, “Reviews: Cottages and Cottage Life” (Horticulturist 3: 181)

- “As to the flower-beds, it is desirable, in any place of considerable extent, to set apart a portion of ground for them; of which some of the windows of the house command a sight, and through which one might go to a grapery or a green-house. But a very beautiful way, is to cut them in circles, or other graceful shapes, upon the edges of the walks, making the soil rich and deep.”

- Downing, A. J., 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (pp. 427–37) [41]

- “In almost all the different kinds of flower-gardens, two methods of forming the beds are observed. One is, to cut the beds out of the green turf, which is ever afterwards kept well-mown or cut for the walks, and the edges pared; the other, to surround the beds with edgings of verdure, as box, etc., or some more durable material, as tiles, or cut stone, the walks between being covered with gravel. . . .

- “The irregular flower-garden is surrounded by an irregular belt of trees and ornamental shrubs of the choicest species, and the beds are varied in outline, as well as irregularly disposed, sometimes grouping together, sometimes standing singly, but exhibiting no uniformity of arrangement. ... [Fig. 12]

- “Where the flower-garden is a spot set apart, of any regular outline, not of large size, and especially where it is attached directly to the house, we think the effect is most satisfactory when the beds or walks are laid out in symmetrical forms. Our reasons for this are these: the flower-garden, unlike distant portions of the pleasure-ground scenery, is an appendage to the house, seen in the same view or moment with it, and therefore should exhibit something of the regularity which characterizes, in a greater or less degree, all architectural compositions; and when a given scene is so small as to be embraced in a single glance of the eye, regular forms are found to be more satisfactory than irregular ones, which, on so small a scale, are apt to appear unmeaning.

- “The French flower-garden is the most fanciful of the regular modes of laying out the area devoted to this purpose. The patterns or figures employed are often highly intricate, and require considerable skill in their formation. . . . The walks are either of gravel or smoothly shaven turf, and the beds are filled with choice flowering plants. It is evident that much of the beauty of this kind of flower-garden, or indeed any other where the figures are regular and intricate, must depend on the outlines of the beds, or parterres of embroidery, as they are called, being kept distinct and clear. To do this effectually, low growing herbaceous plants or border flowers, perennials and annuals, should be chosen, such as will not exceed on an average, one or two feet in height.

- “In the English flower-garden, the beds are either in symmetrical forms and figures, or they are characterized by irregular curved outlines. The peculiarity of these gardens, at present so fashionable in England, is, that each separate bed is planted with a single variety, or at most two varieties of flowers. Only the most striking and showy varieties are generally chosen, and the effect, when the selection is judicious, is highly brilliant. Each bed, in its season, presents a mass of blossoms, and the contrast of rich colors is much more striking than in any other arrangement. No plants are admitted that are shy bloomers, or which have ugly habits of growth, meagre or starved foliage; the aim being brilliant effect, rather than the display of a great variety of curious or rare plants. To bring about more perfectly, and to have an elegant show during the whole season of growth, hyacinths and other fine bulbous roots occupy a certain portion of the beds, the intervals being filled with handsome herbaceous plants, permanently planted, or with flowering annuals and green-house plants renewed every season. . . .

- “The mingled flower-garden, as it is termed, is by far the most common mode of arrangement in this country, though it is seldom well effected. The object in this is to dispose the plants in the beds in such a manner, that while there is no predominance of bloom in any one portion of the beds, there shall be a general admixture of colors and blossoms throughout the entire garden during the whole season of growth.

- “To promote this, the more showy plants should be often repeated in different parts of the garden, or even the same parterre when large, the less beautiful sorts being suffered to occupy but moderate space. The smallest plants should be nearest the walk, those a little taller behind them, and the largest should be furthest from the eye, at the back of the border, when the latter is seen from one side only, or in the centre, if the bed be viewed from both sides. A neglect of this simple rule will not only give the beds, when the plants are full grown, a confused look, but the beauty of the humbler and more delicate plants will be lost amid the tall thick branches of sturdier plants, or removed so far from the spectator in the walks, as to be overlooked.”

- Elder, Walter, 1849, The Cottage Garden of America (pp. 34, 65) [42]

- “EVERY cottage garden in America might have its hot bed. Make the sash six feet long, and three feet wide; the outer frame three inches broad, the laths all running lengthwise, seven inches apart; glaze it with glass seven by nine inches, the panes to lap each other a quarter of an inch, so as to carry off the rains without leaking through; make a box to fit the sash, three feet deep at back, and twenty-eight inches in front, the sides sloping, and a piece of scantling in each corner to nail the boards on and keep it firm. . . .

- “KEEPING THE FLOWER-BEDS CLEAN.

- “THIS is a branch in the keeping of the cottage garden properly belonging to the fair sex; and those of a good disposition take much pleasure in attending to it. Pull out the weeds from among the flowers in the patches, and hoe and rake the beds every two weeks.”

- Jaques, George, January 1852, “Landscape Gardening in New-England” (Horticulturist 7: 36) [43]

- “A man of refinement would in these days, scarcely tolerate a geometrical arrangement of grounds of this extent. Such places admit of a winding carriage-way, leading through a fine lawn studded with groups of trees, irregularly circuitous walks, bordered with various ]]shrubbery\\; here and there a massive forest tree, standing in its full development singly upon the lawn; a summerhouse embowered in the midst of a little retired grove; arabesque forms of flower beds occasionally inserted in the midst of the smooth green of a grass-plot; a vase, pretty even when empty, but better over-flowing with water, which it costs not much to bring in a leaden pipe from some neighboring hill:—such are among the charms which almost seem to make a little paradise of home.”

Images

Inscribed

Thomas Jefferson, Letter describing plans for a "Garden Olitory," c. 1804. See detail.

Thomas Jefferson, Letter describing plans for a "Garden Olitory" [detail], c. 1804. "beds" marked at the foot of the terrace.

Thomas Jefferson, Plan of Monticello with oval and round flower beds [detail], 1807. "1807. April 15.16.18.30 Planted & Sowed flower beds as above. . . . "

Thomas Jefferson, Sketch of the garden and flower beds at Monticello, June 7, 1807. "oval beds of flowering shrubs" [written on reverse]

Anonymous, "The Irregular Flower-garden," in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), p. 428, fig. 76. "the flower-beds b"

Anonymous, "The Flower-Garden at Dropmore," in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), p. 431, fig. 77. Shown alongside a list of the plants which occupy each of the beds

Anonymous, "English Flower-Garden," in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), p. 434, fig. 78. "c, d, are the flower-beds"

Associated

- 1263.jpg

c. 1850, Vassar

Attributed

- 1452.jpg

c. 1785-90, R.I. Historical Society

- 0649.jpg

1815, New Haven Museum

- 1461.jpg

1824

Notes

- ↑ Hot beds, which used either an internal or external source for warming the soil, were particularly popular for raising young or exotic plants.

- ↑ See Mark Laird, “Ornamental Planting and Horticulture in English Pleasure Grounds, 1700–1830,” in Garden History: Issues, Approaches, Methods, ed. John Dixon Hunt (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1992b), 243–77, view on Zotero, and Mark Laird, “ ‘Our Equally Favorite Hobby Horse’: The Flower Gardens of Lady Elizabeth Lee at Hartwell and the 2nd Earl Harcourt at Nuneham Courtenay,” Garden History 18 (Autumn 1990): 103–54, view on Zotero. For a synthetic history of the display of flowers in eighteenth-century British gardens, see Mark Laird, The Flowering of the Landscape Garden: English Pleasure Grounds, 1720–1800 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alice B. Lockwood, ed., Gardens of Colony and State: Gardens and Gardeners of the American Colonies and of the Republic before 1840, 2 vols (New York: Charles Scribner’s for the Garden Club of America, 1931), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Elise Pinckney, Thomas and Elizabeth Lamboll: Early Charleston Gardeners, Charleston Museum Leaflet, No. 28 (Charleston, S.C.: Charleston Museum, 1969), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 William Parker Cutler, Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL. D (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Karen Madsen, ‘William Hamilton’s Woodlands’, 1988, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bentley, The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts (Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith, 1962), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John C. Ogden, An Excursion into Bethlehem & Nazareth, in Pennsylvania, in the Year 1799 (Philadelphia: Charles Cist, 1800), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edwin M. Betts and Hazlehurst Bolton Perkins, Thomas Jefferson’s Flower Garden at Monticello (Charlottesville, Va.: Thomas Jefferson Foundation, University of Virginia, 1986), view on Zotero.

- ↑ S. Allen Chambers, Jr., Poplar Forest and Thomas Jefferson (Forest, Va.: Corporation for Jefferson’s Poplar Forest, 1993), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frances Milton Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans, 2nd edn, 2 vols (London: Wittaker, Treacher & Co., 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Malthus A. Ward, An Address Pronounced Before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (Boston: J. T. & E. Buckingham, 1831), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, ‘Some Remarks upon Several Gardens and Nurseries, in Providence, Burlington, (N.J.) and Balitmore’, The Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs, 5 (1839), 361–76, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Silk Buckingham, The Eastern and Western States of America, 3 vols (London: Fisher, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, ‘Select Villa Residences, with Descriptive Notices of Each; Accompanied with Remarks and Observations on the Principles and Practice of Landscape Gardening: Intended with a View to Illustrate the Art of Laying Out, Arranging, and Forming Gardens and Ornamental Grounds’, The Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs, 7 (1841), 401–11, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, ‘Notes Made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and Intermediate Places, from August 8th to the 23rd, 1841’, The Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs, 8 (1842), 121–29, view on Zotero

- ↑ Suzanne Turner, Historic Landscape Report: The Landscape at the Shadows-on-the-Teche (New Ibera, La.: Shadows-on-the-Teche, 1993), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, ‘Notes of a Visit to Several Gardens in the Vicinity of Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, in October, 1845’, The Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs, 12 (1846), 241–48, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jacquetta M. Haley, ed., Pleasure Grounds: Andrew Jackson Downing and Montgomery Place (Tarrytown, N.Y.: Sleepy Hollow Press, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, ‘Description of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, with Remarks’, The American Journal of Insanity, 4 (1848), 347–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Deborah Norris Logan, The Norris House (Philadelphia: Fair-Hill Press, 1867), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Worlidge, Systema Agriculturae, The Mystery of Husbandry Discovered (London: T. Johnson, 1669), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jean de La Quintinie, The Compleat Gard’ner, or Directions for Cultivating and Right Ordering of Fruit-Gardens and Kitchen Gardens, trans. by John Evelyn (New York: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Bradley, Dictionarium Botanicum, or A Botanical Dictionary for the Use of the Curious in Husbandry and Gardening, 2 vols (London: Printed for T. Woodward and J. Peele, 1728), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . ., 5th edn, 2 vols (London: D. Midwinter et al, 1741), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas A. Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews...., 5th edn (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, Encyclopaedia, or A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature, 18 vols (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1798), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Marshall, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening, 1st American ed. from the 2nd London ed., 2 vols (Boston: Samuel Etheridge, 1799), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Gardiner and David Hepburn, The American Gardener, Containing Ample Directions for Working a Kitchen Garden Every Month in the Year, and Copious Instructions for the Cultivation of Flower Gardens, Vineyards, Nurseries, Hop Yards, Green Houses and Hot Houses (Washington, D.C.: Printed by Samuel H. Smith, 1804), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M’Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done... for Every Month of the Year.... (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Grant Thorburn, The Gentleman and Gardener’s Kalender for the Middle States of North America, 2nd edn (New York: E. B. Gould, 1817), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Prince, A Short Treatise on Horticulture (New York: T. and J. Swords, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Bridgeman, The Young Gardener’s Assistant, 3rd edn (New York: Geo. Robertson, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Fessenden, ed., The New American Gardener, 7th edn (Boston: Russell, Odiorne, 1833), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James E. Teschemacher, ‘On Horticultural Architecture’, The Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine, 1 (1835), 409–12, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Sayers, The American Flower Garden Companion, Adapted to the Northern States (Boston: Joseph Breck and Company, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. by David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th edn (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter Elder, The Cottage Garden of America (Philadelphia: Moss, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jaques, George, ‘Landscape Gardening in New-England’, The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, 7 (1852), 33–36, view on Zotero.