Difference between revisions of "Deer park"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m (→Images) |

A-Whitlock (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

Despite the proliferation of British definitions of deer park, American authors such as [[Noah Webster]] (1828) typically discussed it as a subcategory of the term “[[park]].” The American context yields only a few examples, which are mostly located in the mid-Atlantic region; thus the feature was relatively rare in America, despite the prevalence of white-tailed deer throughout the East Coast during the colonial and federal periods. Notably, however, deer cannot be truly domesticated and can be kept only in a semi-domesticated state from which humans can cull the species.<ref>Juliet Clutton-Brock, ''Domesticated Animals from Early Times'' (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 182–83, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUWC3TB2 view on Zotero].</ref> There were several reasons that the deer park was a feature that generally belonged to private landowners and not the public community. The lack of demarcated hunting areas in the colonial and federal periods in addition to the costs of devoting land to deer instead of more productive animals, such as cattle, prohibited their development. Nevertheless, the few deer parks identified indicate that the feature had both symbolic and practical value. | Despite the proliferation of British definitions of deer park, American authors such as [[Noah Webster]] (1828) typically discussed it as a subcategory of the term “[[park]].” The American context yields only a few examples, which are mostly located in the mid-Atlantic region; thus the feature was relatively rare in America, despite the prevalence of white-tailed deer throughout the East Coast during the colonial and federal periods. Notably, however, deer cannot be truly domesticated and can be kept only in a semi-domesticated state from which humans can cull the species.<ref>Juliet Clutton-Brock, ''Domesticated Animals from Early Times'' (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 182–83, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUWC3TB2 view on Zotero].</ref> There were several reasons that the deer park was a feature that generally belonged to private landowners and not the public community. The lack of demarcated hunting areas in the colonial and federal periods in addition to the costs of devoting land to deer instead of more productive animals, such as cattle, prohibited their development. Nevertheless, the few deer parks identified indicate that the feature had both symbolic and practical value. | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:2260.jpg|thumb|450 px|Fig. 2, Unknown,Painting of a Landscape with a Stag Hunt, Unknown maker, 1800–50.]] |

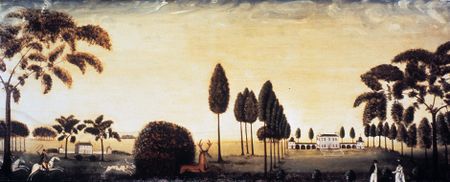

An early representation of a deer park is the overmantle painting from Morattico Hall in Virginia [Fig. 1]. To the left, sharply demarcated from the urbanized mansion houses surrounding the harbor, is a panoramic landscape with deer and elegantly dressed hunters. This luxurious (and highly fictionalized) setting suggests that the keeping of deer in parks for pleasure hunting was one of many signifiers of wealth and status in the colonial period. Many painted landscape views featured deer in a park-like setting [Fig. 2]. | An early representation of a deer park is the overmantle painting from Morattico Hall in Virginia [Fig. 1]. To the left, sharply demarcated from the urbanized mansion houses surrounding the harbor, is a panoramic landscape with deer and elegantly dressed hunters. This luxurious (and highly fictionalized) setting suggests that the keeping of deer in parks for pleasure hunting was one of many signifiers of wealth and status in the colonial period. Many painted landscape views featured deer in a park-like setting [Fig. 2]. | ||

| Line 149: | Line 149: | ||

File:0463.jpg|Anonymous, Overmantel painting from Morattico Hall, 1715. | File:0463.jpg|Anonymous, Overmantel painting from Morattico Hall, 1715. | ||

| − | File: | + | File:2260.jpg|Painting of a Landscape with a Stag Hunt, Unknown maker, Massachusetts, United States, 1800-1850, Oil on panel (white pine), 1964.2101, Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont, Courtesy of Winterthur Museum. |

File:0124.jpg|Jane Shearer, Brick House with [[Terrace/Slope|Terraces]], 1806, in Sotheby’s New York, ''Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring'' (January 2012): 80. | File:0124.jpg|Jane Shearer, Brick House with [[Terrace/Slope|Terraces]], 1806, in Sotheby’s New York, ''Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring'' (January 2012): 80. | ||

Revision as of 13:19, July 16, 2020

See also: Park

History

Despite the proliferation of British definitions of deer park, American authors such as Noah Webster (1828) typically discussed it as a subcategory of the term “park.” The American context yields only a few examples, which are mostly located in the mid-Atlantic region; thus the feature was relatively rare in America, despite the prevalence of white-tailed deer throughout the East Coast during the colonial and federal periods. Notably, however, deer cannot be truly domesticated and can be kept only in a semi-domesticated state from which humans can cull the species.[1] There were several reasons that the deer park was a feature that generally belonged to private landowners and not the public community. The lack of demarcated hunting areas in the colonial and federal periods in addition to the costs of devoting land to deer instead of more productive animals, such as cattle, prohibited their development. Nevertheless, the few deer parks identified indicate that the feature had both symbolic and practical value.

An early representation of a deer park is the overmantle painting from Morattico Hall in Virginia [Fig. 1]. To the left, sharply demarcated from the urbanized mansion houses surrounding the harbor, is a panoramic landscape with deer and elegantly dressed hunters. This luxurious (and highly fictionalized) setting suggests that the keeping of deer in parks for pleasure hunting was one of many signifiers of wealth and status in the colonial period. Many painted landscape views featured deer in a park-like setting [Fig. 2].

Accounts of actual deer parks support this thesis. Deer parks generally belonged to wealthy landowners who were anxious to display their prominent status. In 1830, Gen. John Mason, for example, noted that his father, a prominent Virginia landowner and political figure, created a fenced-in deer park, occupying an entire “plain” and “in full view” from the garden at Gunston Hall. Situating the deer park next to the garden would have given viewers from the house the impression of extensive land holdings.

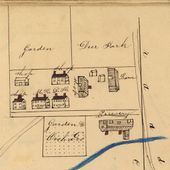

Several descriptions and images of the deer park at Mount Vernon emphasize the value George Washington placed on the animals. Although Washington used the phrase “deer paddock” to refer to this area between the house and the river, other writers, such as Jedidiah Morse and Isaac Weld, called it the deer park. Letters between Washington and George Fairfax indicate that Washington received deer from several friends, suggesting that the practice of exchanging deer reinforced social relationships.[2] In addition, the deer park offered a ready supply of food, as well as prominent evidence of the landowner’s ability to devote acreage to nonagricultural products. In the case of Eleutherian Mills, in Wilmington, Del., the deer park was located next to a piazza, and the family’s pet deer provided a source of entertainment, as noted by Sophie Madeleine du Pont (1826) [Fig. 3].

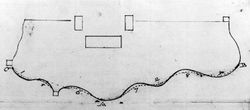

The destruction caused by deer at Mount Vernon illustrated the need for enclosure in deer parks. This also was noted by Webster in his definition of park. Washington, for example, bounded his deer park with a fence, depicted in a painting from 1792 [Fig. 4]. He also used a sinuous brick deer wall or ha-ha, which he drew in plan and described in a letter of 1798 (see Ha-Ha) [Fig. 5]. Similarly, an early nineteenth-century view of the Shaker community of Whitewater, Ohio, delineated an enclosed deer park as one of the various productive components of the town. Without such an enclosure, either at Whitewater or at Mount Vernon, a deer park would have been incompatible with agricultural production.

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Gooch, Lt. Gov. William, 1727, describing the Governor’s Palace, Williamsburg, VA (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 110)[3]

- “[The Governor’s Palace contained] an handsome garden, an orchard full of fruit, and a very large Park. [He intended to turn the park] to better use I think than Deer, which is feeding off of all sorts of Cattle.”

- Fisher, Daniel, 25 May 1755, describing the Proprietor’s Garden, Philadelphia (quoted in Pecquet du Bellet 1907: 2:802)[4]

- “. . . descending from the House is a neat little Park tho’ I am told there are no Deer in it.”

- Burnaby, Rev. Andrew, 1760, describing a park and garden near the Passaic River, NJ (Burnaby 1775: 57)[5]

- “I went down two miles farther to the park and gardens of. . . colonel Peter Schuyler. In the gardens is a very large collection of citrons, oranges, limes, lemons, balsams of Peru, aloes, pomegranates, and other tropical plants; and in the park I saw several American and English deer, and three or four elks or moose-deer.”

- Ecuyer, Capt. Simeon, April 1764, describing Fort Pitt, Pittsburgh, PA (quoted in Stotz 1970: 14)[6]

- “. . . the deer park, the little garden, and the bowling green, I am just now making into one garden, it will be extreamly [sic] pretty and very useful to this garrison, the King’s garden will be put in proper order.”

- Morse, Jedidiah, 1789, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1789: 381)[7]

- “A small park on the margin of the river, where the English fallow-deer, and the American wild-deer are seen through the thickets, alternately with the vessels as they are sailing along, add a romantic and picturesque appearance to the whole scenery.” [See Fig. 4]

- Weld, Isaac, 1799, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1799: 53)[8]

- “The ground in the rear of the house is also laid out in a lawn, and the declivity of the Mount, towards the water, in a deer park.”

- Bryant, William Cullen, August 25, 1821, in a letter to his wife, Frances F. Bryant, describing the Vale, estate of Theodore Lyman, Waltham, MA (1975: 1:108–9)[9]

- “He took me to the seat of Mr. Lyman. . . It is a perfect paradise. . . North of the house was a park, with a few American deer in it and a large herd of spotted deer—a beautiful animal imported from Bengal.”

- du Pont, Sophie Madeleine, 1824 and 1826, describing Eleutherian Mills, estate of Eleuthère Irénée du Pont, near Wilmington, DE (quoted in Low and Hinsley 1987: 47, 92–93)[10]

- “[November 17, 1824] Azore [a stag] begins to make great use of his horns—Mr. Brilliant (a frenchman who works in the refinery,) plagueing him with Stephens, through the bars of the gate— a little after dinner Mr Delages went to go down and Brilliant accompanied him[.] Azore let Mr Delages pass but he flew at Brilliant and threw him down—Stephens seized him by the horns and pulled him away—Brilliant got up again, but no sooner was Azore loose than he attacked him again, pushed him over the wall in front of the piazza and jumped over after him—Alex arrived and gave Azore a knock on the head with a stick of wood which hurt him a good deal—they at length succeeded in getting Brilliant away—ever since this the men are so much afraid of Azore that they will not pass thro’ the [deer] park though he is gentle as ever with us. . .

- “[September 25, 1826] This morning the little Italian (you know, that dwarf who works in the refinery) went into the [deer] park to arrange something about the large well—Azore [the family’s pet stag] rushed on him, cut him severely on his breast and his leg—He came here to have his wounds dressed by Mama and notwithstanding the sympathy we felt for what he suffered, we could hardly help laughing at his description of the adventure—‘He threw me down and gave me a somerset’ &c &c ‘I went to help myself over the fence, and the fellow came to help me’ &c &c. The [Deer] Park shellbarks are fully ripe, but Azore eats almost all that fall, besides which we are too much afraid of his lordship to trust ourselves long in his presence.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, 1829, describing Wye House, estate of Col. Edward Lloyd, Talbot County, MD (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:147)[11]

- “The Coll. is possessed of immence property, he had 400 Ars. of land in a park to keep Deer, round which was a fence of 20 rails high, Maise were planted within for sustenance of his deer.”

- Mason, John, 1830s, describing Gunston Hall, seat of George Mason, Mason Neck, VA (Gunston Hall Archives, John Mason “Recollections”)

- “On this front you descended directly into an extensive Garden-touching the house on one side & reduced from the natural irregularity of the Hill top, to perfect level Platform, the Southern extremity of which was bounded by a Spacious walk running eastwardly & westwardly, from which there was by the natural & sudden declivity of the Hill a rapid descent to the plain considerably below it. On this plain adjoining the Margin of the Hill opposite to & in full view from the Garden was was [sic] a Deer park studded with Trees kept well fenced and stocked with Native Deer domesticated.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., 1841, describing the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia (1841: 18)[12]

- “Immediately in front of the Hospital, is a lawn forming a segment of a circle, in which is a circular rail road. To the east of this, and passing into the woods, is the deer-park, surrounded by a high pallisade, and forming an effectual and not unsightly division of the ground appropriated to the different sexes; from various points of which, and from the whole eastern front of the building, it is seen to much advantage.” [Fig. 6]

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1850, describing Waltham House at the Vale, estate of Theodore Lyman, Waltham, MA (1850: 330)[13]

- “844. Waltham House. . . There is an extensive park, containing about forty deer, principally of the Bengal breed (Downing’s Landscape Gardening.)”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), September 1850, “Notes on Gardens and Nurseries,” describing Bellmont Place, residence of John Perkins Cushing, Watertown, MA (Magazine of Horticulture 16: 412)[14]

- “The new and elegant mansion, so long vacant, is now occupied by the proprietor, and an air of liveliness, which they did not before possess, is now communicated to the park, the pleasure-ground and the garden. . . The vast expanse of park, which adds so much to the character of the old English residence, would possess only half the attraction it now does, but for the herds of deer which traverse its bounds, giving life and animation to the scene.”

Citations

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (1789: n.p.)[15]

- “PARK, pa’rk. s. A piece of ground inclosed and stored with deer and other beasts of chase.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2: n.p.)[16]

- “P`ARK, n. [Sax. parruc, pearruc; Scot. parrok; W. parc; Fr. id.; It. parco; Sp. parque; Ir. pairc; G. Sw. park; D. perk. . .]

- “A large piece of ground inclosed and privileged for wild beasts of chase, in England, by the king’s grant or by prescription. To constitute a park, three things are required; a royal grant or license; inclosure by pales, a wall or hedge; and beasts of chase, as deer, &c. Encyc.

- “Park of artillery, or artillery park, a place in the rear of both lines of an army for encamping the artillery, which is formed in lines, the guns in front, the ammunition-wagons behind the guns. . . Encyc. . .

- “Park of provisions, the place where the sutlers pitch their tents and sell provisions, and that where the bread wagons are stationed.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 418)[17]

- “PARK, in the modern acceptation of the word, is an extensive adorned inclosure surrounding the house and gardens, and affording pasturage either to deer or cattle. In Great Britain, a park, strictly and legally, is a large extent of a man’s own ground inclosed and privileged for wild beasts of chase by prescription or by royal grant. (Coke’s Litt. 233. a. Blackstone, 2. 38.). . . It has been decided by the superior courts of law, that to constitute a park these circumstances are essential:—1. A grant from the king, or prescription. 2. That it be inclosed by a wall, pale, or hedge. 3. That it contain beasts of park, and if it fail in any one of these, it is a total disparking. (Croke Car. 59.) Of such parks there are said to be 781 in England. (Brooks Abr. Action sur Stat. 48.)”

Images

Inscribed

George Kendall, “View of Whitewater,” Ohio [detail], 1835.

Thomas S. Sinclair, “Plan of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane at Philadelphia,” in Thomas S. Kirkbride, American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4 (April 1848): plate opp. 280.

Associated

Samuel Vaughan, Plan of Mount Vernon, 1787.

Edward Savage, The East Front of Mount Vernon, c. 1787–92.

George Washington, Drawing and Notes for a Ha-Ha Wall at Mount Vernon, October 1798, 1798.

Victor de Grailly, The Tomb at Mount Vernon, c. 1840—50.

W. Mason, “Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane,” c. 1841, in Thomas S. Kirkbride, Reports of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane: for the Year 1841 (1841), frontispiece.

Attributed

Jane Shearer, Brick House with Terraces, 1806, in Sotheby’s New York, Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring (January 2012): 80.

Anthony St. John Baker (artist), B. King (lithographer), Riversdale, near Bladensburg, 1827.

Thomas Worthington Whittredge, View of Cincinnati, c. 1840–45. Worcester Art Museum, MA.

Notes

- ↑ Juliet Clutton-Brock, Domesticated Animals from Early Times (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 182–83, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, eds., The Diaries of George Washington, vol. 4 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976–79), 184, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Louise Pecquet du Bellet, ed., Some Prominent Virginia Families, 4 vols. (Lynchburg, VA: J. P. Bell, 1907), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Burnaby, Travels through the Middle Settlements in North-America, in the Years 1759 and 1760, 2nd ed. (London: Printed for T. Payne, 1775), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Morse Stotz, Point of Empire, Conflict at the Forks of the Ohio (Pittsburgh: Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania, 1970), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jedidiah Morse, The American Geography; Or, A View of the Present Situation of the United States of America (Elizabeth Town, NJ: Shepard Kollock, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Isaac Weld, Travels through the States of North America and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, during the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797 (London: John Stockdale, 1799), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Cullen Bryant, The Letters of William Cullen Bryant, ed. William Cullen II Bryant and Thomas G. Voss (New York: Fordham University Press, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Betty-Bright Low and Jacqueline Hinsley, Sophie du Pont, A Young Lady in America: Sketches, Diaries, & Letters, 1823–1833 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family: Charles Willson Peale, vol. 5, The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, Report of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane: for the Year 1841 (Philadelphia: Board of Managers, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed. (London: Longman et al., 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ C. M. Hovey, “Notes on Gardens and Nurserues,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 16, no. 9 (September 1850): 406–17, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas A. Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews. . ., 5th ed. (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.