Difference between revisions of "Orangery"

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

The term orangery described both a grove of orange trees and a structure in which citrus trees were cultivated. [[William Bartram]] used the term in 1791 to describe a [[grove]] of native trees left standing within a cleared ground and incorporated into a designed [[plantation]], and, therefore, a natural feature in the landscape. Samuel Johnson (1755) and [[Noah Webster]] (1848) defined an orangery as an area where orange trees were planted, or as [[Ephraim Chambers]] (1741–43) wrote, “used for the [[parterre]].” John Evelyn, in his 1693 translation of Jean de La Quintinie, used the term to refer to any place stocked with orange trees, whether indoors or out. The most common usage, however, refers to the architecture of plant-keeping houses, often synonymous with [[greenhouse]], [[hothouse]], or [[conservatory]]. In this sense, the orangery could be a separate building, or a structure that was either part of or attached to a [[greenhouse]] in which citrus and other exotic fruits and flowers were kept [Fig. 1]. | The term orangery described both a grove of orange trees and a structure in which citrus trees were cultivated. [[William Bartram]] used the term in 1791 to describe a [[grove]] of native trees left standing within a cleared ground and incorporated into a designed [[plantation]], and, therefore, a natural feature in the landscape. Samuel Johnson (1755) and [[Noah Webster]] (1848) defined an orangery as an area where orange trees were planted, or as [[Ephraim Chambers]] (1741–43) wrote, “used for the [[parterre]].” John Evelyn, in his 1693 translation of Jean de La Quintinie, used the term to refer to any place stocked with orange trees, whether indoors or out. The most common usage, however, refers to the architecture of plant-keeping houses, often synonymous with [[greenhouse]], [[hothouse]], or [[conservatory]]. In this sense, the orangery could be a separate building, or a structure that was either part of or attached to a [[greenhouse]] in which citrus and other exotic fruits and flowers were kept [Fig. 1]. | ||

| − | [[File:0180.jpg|thumb|Fig. | + | [[File:0180.jpg|thumb|Fig. 3, Anonymous, Fairhill, ''The Seat of Isaac Norris Esq.'', 18th century. The orangery is located to the left and rear of the main house.]] |

| − | [[File:1770.jpg|thumb|Fig. | + | [[File:1770.jpg|thumb|Fig. 4, [[J. C. Loudon]], Orangery at Pimlico, in ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (1826), p. 813, fig. 570.]] |

The term “orangery” originated in Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when citrus fruit was highly valued. The orangery was a showcase for the nobility with the best-known examples found at Versailles, St. Petersburg, and Vienna. In eighteenth-century America, however, the term seems to have been used rarely outside garden treatises. Perhaps its aristocratic associations made Americans reluctant to use it. The more generic terms “[[greenhouse]]” and “[[conservatory]]” replaced it, as did specific names used to describe its precise contents, such as “pinery” (for pineapples), “peachery,” and “grapery” or “vinery.” | The term “orangery” originated in Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when citrus fruit was highly valued. The orangery was a showcase for the nobility with the best-known examples found at Versailles, St. Petersburg, and Vienna. In eighteenth-century America, however, the term seems to have been used rarely outside garden treatises. Perhaps its aristocratic associations made Americans reluctant to use it. The more generic terms “[[greenhouse]]” and “[[conservatory]]” replaced it, as did specific names used to describe its precise contents, such as “pinery” (for pineapples), “peachery,” and “grapery” or “vinery.” | ||

| − | [[File:1779.jpg|thumb|Fig. | + | [[File:1779.jpg|thumb|Fig. 5, [[J. C. Loudon]], Orangery at Baden Gardens, in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'' (1834), p. 174, fig. 130.]] |

| − | [[File:1645.jpg|thumb|Fig. | + | [[File:1645.jpg|thumb|Fig. 6, Robert B. Leuchars, Orangery at Clifton Mansion, in A Practical Treatise on the Construction, Heating, and Ventilation of Hothouses (1850), fig. 14.]] |

Although several imported treatises contain the term “orangery,” it is conspicuously absent in major American publications by Bernard M’Mahon, C. M. Hovey, and [[A. J. Downing]]—except when describing eighteenth-century [[greenhouse]]s. For example, in 1837 Hovey used orangery to describe Bartram’s by-then venerable century-old greenhouse in Philadelphia. In his “Historical Sketches,” Downing described the eighteenth-century greenhouses at William Hamilton’s seat, [[the Woodlands]], as orangeries. These colonial greenhouses were called orangeries in the nineteenth century because they represented an older building type that was characterized by unglazed roofs. This earlier type of plant-keeping structure, built of stone or brick with large windows and a solid, unglazed roof was found at Wye House [Fig. 2]; Fairhill [Fig. 3]; and Lt. Gov. James Hamilton’s estate, Bush Hill, near Philadelphia. This type had an architectural style consistent with the main house, with a regular entablature and cornice and large windows that were often roundheaded, separated by [[column]]s or piers. At the time they were built, they were most probably [[greenhouse]]s, [[hothouse]]s, or [[conservatories]], although it is clear that they were used for keeping citrus trees (see [[Greenhouse]] and [[Hothouse]] for a discussion of heating systems). | Although several imported treatises contain the term “orangery,” it is conspicuously absent in major American publications by Bernard M’Mahon, C. M. Hovey, and [[A. J. Downing]]—except when describing eighteenth-century [[greenhouse]]s. For example, in 1837 Hovey used orangery to describe Bartram’s by-then venerable century-old greenhouse in Philadelphia. In his “Historical Sketches,” Downing described the eighteenth-century greenhouses at William Hamilton’s seat, [[the Woodlands]], as orangeries. These colonial greenhouses were called orangeries in the nineteenth century because they represented an older building type that was characterized by unglazed roofs. This earlier type of plant-keeping structure, built of stone or brick with large windows and a solid, unglazed roof was found at Wye House [Fig. 2]; Fairhill [Fig. 3]; and Lt. Gov. James Hamilton’s estate, Bush Hill, near Philadelphia. This type had an architectural style consistent with the main house, with a regular entablature and cornice and large windows that were often roundheaded, separated by [[column]]s or piers. At the time they were built, they were most probably [[greenhouse]]s, [[hothouse]]s, or [[conservatories]], although it is clear that they were used for keeping citrus trees (see [[Greenhouse]] and [[Hothouse]] for a discussion of heating systems). | ||

| − | [[File:0340.jpg|thumb|Fig. | + | [[File:0340.jpg|thumb|Fig. 7, Mutual Assurance Society, Richmond, Declaration for Assurance Book, vol. 26, policy no. 2049, Insurance policy drawings for Mount Vernon, March 13, 1803.]] |

This type of greenhouse construction fell out of fashion once gardeners began to realize the benefits of increased light and perpendicular light for growing plants. As a greater proportion of glazing became technically possible with cast-iron construction, the design of plant houses shifted from the shingle-roofed brick or stone orangery to the glasshouse [Fig. 4]. With these changes in structure and material, [[J. C. Loudon]], writing in the early nineteenth century, concluded that the orangery was the [[greenhouse]] of the previous century [Fig. 5]. Thus, nineteenth-century authors writing about historical greenhouses distinguished them from the cast-iron and glass structures by calling them orangeries. Twentieth-century garden historians and archaeologists have continued this practice. The orangery, however, did not completely disappear as an option in new construction. [[Jane Loudon]] provided a late reference in 1845 when she wrote that the orangery was a house with an opaque roof intended only for orange trees. She asserted the suitability of non-greenhouse construction to that use. Further evidence of the orangery’s continued use is in Robert B. Leuchars’s 1850 ''Practical Treatise on the Construction, Heating, and Ventilation of Hothouses'', in which he described John Hopkins’s very large structure at Clifton Mansion [Fig. 6]. | This type of greenhouse construction fell out of fashion once gardeners began to realize the benefits of increased light and perpendicular light for growing plants. As a greater proportion of glazing became technically possible with cast-iron construction, the design of plant houses shifted from the shingle-roofed brick or stone orangery to the glasshouse [Fig. 4]. With these changes in structure and material, [[J. C. Loudon]], writing in the early nineteenth century, concluded that the orangery was the [[greenhouse]] of the previous century [Fig. 5]. Thus, nineteenth-century authors writing about historical greenhouses distinguished them from the cast-iron and glass structures by calling them orangeries. Twentieth-century garden historians and archaeologists have continued this practice. The orangery, however, did not completely disappear as an option in new construction. [[Jane Loudon]] provided a late reference in 1845 when she wrote that the orangery was a house with an opaque roof intended only for orange trees. She asserted the suitability of non-greenhouse construction to that use. Further evidence of the orangery’s continued use is in Robert B. Leuchars’s 1850 ''Practical Treatise on the Construction, Heating, and Ventilation of Hothouses'', in which he described John Hopkins’s very large structure at Clifton Mansion [Fig. 6]. | ||

Revision as of 14:43, March 22, 2017

(Orangerie)

See also: Conservatory, Greenhouse, Hothouse, Nursery

History

The term orangery described both a grove of orange trees and a structure in which citrus trees were cultivated. William Bartram used the term in 1791 to describe a grove of native trees left standing within a cleared ground and incorporated into a designed plantation, and, therefore, a natural feature in the landscape. Samuel Johnson (1755) and Noah Webster (1848) defined an orangery as an area where orange trees were planted, or as Ephraim Chambers (1741–43) wrote, “used for the parterre.” John Evelyn, in his 1693 translation of Jean de La Quintinie, used the term to refer to any place stocked with orange trees, whether indoors or out. The most common usage, however, refers to the architecture of plant-keeping houses, often synonymous with greenhouse, hothouse, or conservatory. In this sense, the orangery could be a separate building, or a structure that was either part of or attached to a greenhouse in which citrus and other exotic fruits and flowers were kept [Fig. 1].

The term “orangery” originated in Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when citrus fruit was highly valued. The orangery was a showcase for the nobility with the best-known examples found at Versailles, St. Petersburg, and Vienna. In eighteenth-century America, however, the term seems to have been used rarely outside garden treatises. Perhaps its aristocratic associations made Americans reluctant to use it. The more generic terms “greenhouse” and “conservatory” replaced it, as did specific names used to describe its precise contents, such as “pinery” (for pineapples), “peachery,” and “grapery” or “vinery.”

Although several imported treatises contain the term “orangery,” it is conspicuously absent in major American publications by Bernard M’Mahon, C. M. Hovey, and A. J. Downing—except when describing eighteenth-century greenhouses. For example, in 1837 Hovey used orangery to describe Bartram’s by-then venerable century-old greenhouse in Philadelphia. In his “Historical Sketches,” Downing described the eighteenth-century greenhouses at William Hamilton’s seat, the Woodlands, as orangeries. These colonial greenhouses were called orangeries in the nineteenth century because they represented an older building type that was characterized by unglazed roofs. This earlier type of plant-keeping structure, built of stone or brick with large windows and a solid, unglazed roof was found at Wye House [Fig. 2]; Fairhill [Fig. 3]; and Lt. Gov. James Hamilton’s estate, Bush Hill, near Philadelphia. This type had an architectural style consistent with the main house, with a regular entablature and cornice and large windows that were often roundheaded, separated by columns or piers. At the time they were built, they were most probably greenhouses, hothouses, or conservatories, although it is clear that they were used for keeping citrus trees (see Greenhouse and Hothouse for a discussion of heating systems).

This type of greenhouse construction fell out of fashion once gardeners began to realize the benefits of increased light and perpendicular light for growing plants. As a greater proportion of glazing became technically possible with cast-iron construction, the design of plant houses shifted from the shingle-roofed brick or stone orangery to the glasshouse [Fig. 4]. With these changes in structure and material, J. C. Loudon, writing in the early nineteenth century, concluded that the orangery was the greenhouse of the previous century [Fig. 5]. Thus, nineteenth-century authors writing about historical greenhouses distinguished them from the cast-iron and glass structures by calling them orangeries. Twentieth-century garden historians and archaeologists have continued this practice. The orangery, however, did not completely disappear as an option in new construction. Jane Loudon provided a late reference in 1845 when she wrote that the orangery was a house with an opaque roof intended only for orange trees. She asserted the suitability of non-greenhouse construction to that use. Further evidence of the orangery’s continued use is in Robert B. Leuchars’s 1850 Practical Treatise on the Construction, Heating, and Ventilation of Hothouses, in which he described John Hopkins’s very large structure at Clifton Mansion [Fig. 6].

Scholars have pointed out that in the early colonial period, several greenhouses for citrus cultivation were built by wealthy families who had access to international trade networks. It took skill and money to build a good greenhouse for citrus because glass was expensive, servants were required to maintain it, and skilled gardeners needed to cultivate the fruit. [1] Therefore, they were associated with the privileged and cultured elite [Fig. 7]. Archaeologist Carmen Weber has argued that this association was so well established in the colonial period that in a portrait of Margaret Tilghman Carroll by Charles Willson Peale the simple inclusion of orange leaves was sufficient to symbolize and convey her control of property and considerable wealth. [2]

-- Therese O'Malley

Texts

Usage

- Shippen, Thomas Lee, 1790, describing Stratford, estate of Thomas Lee, Westmoreland County, Va. (quoted in Lockwood 1934: 2:68) [3]

- “It was with difficulty that my Uncles, who accompanied me, could persuade me to leave the hall to look at the gardens, vineyards, orangeries and lawns which surround the house.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing Marshall Plantation, on the San Juan River, Fla. (1928: 84) [4]

- “In the afternoon, the most sultry time of the day, we retired to the fragrant shades of an orange grove. The house was situated on an eminence, about one hundred and fifty yards from the river. On the right hand was the orangery, consisting of many hundred trees, natives of the place, and left standing, when the ground about it was cleared. These trees were large, flourishing, and in perfect bloom, and loaded with their ripe golden fruit. On the other side was a spacious garden, occupying a regular slope of ground down to the water; and a pleasant lawn lay between.”

- Hovey, C. M., June 1837, describing Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, vicinity of Philadelphia, Pa. (Magazine of Horticulture 3: 210)

- “In the orangery attached to the large greenhouse are a great number of very old orange and lemon trees.”

- Loudon, J. C., December 1839, describing Cheshunt Cottage, property of William Harrison, near London, England (Gardener's Magazine 15: 644) [5]

- "3. The orangery. The paths are of slate, and the centre bed, or pit, for the orange trees, is covered with an open wooden grating, on which are placed the smaller pots; while the larger ones, and the boxes and tubs, are let down through openings made in the grating, as deep as it may be necessary for the proper effect of the heads of the trees. This house, and that for Orchidàceæ, are heated from the boiler. . . . " [Fig. 8]

- Downing, A. J., 1849, describing the Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, Pa. (p. 42) [6]

- “at a time when the introduction of rare exotics was attended with a vast deal of risk and trouble, the extensive green-houses and orangeries of this seat contained all the richest treasures of the exotic flora.”

Citations

- La Quintinie, Jean de, 1693, “Dictionary,” The Compleat Gard’ner ([1693] 1982: n.p.) [7]

- “Orangery is a place stocked with Orange Trees, whether within doors or without.”

- Bradley, Richard, 1720, New Improvements of Planting and Gardening (2.3: 113, 115–16) [8]

- “when I consider how much the Beauty and Advantage of the Orangery is owing to the good Condition of the Conservatory, I am the less surprized to meet every Day with valuable Collections of Trees half poison’d with Charcoal, or pinch’d to Death with the Frosts. . . .

- “[referring to Plate II] D D are the Benches for the most hardy Green-House Plants, such as Orange, Limons, Myrtles, &c. they are so disposed, as to admit of Walks about them, for convenience of Watering. . ..

- “I leave every one to judge how great an Ornament this will be, as well in Winter, when the Plants are in the House; and in Summer, when the House will be made a Room of Entertainment.”

- Langley, Batty, 1728, New Principles of Gardening ([1728] 1982: 195–98) [9]

- “General DIRECTIONS, &c....

- “XIX. That in those serpentine Meanders, be placed at proper Distances, large Openings, which you surprizingly come to . . . and from thence through small Inclosures of Corn, open Plains, of small Meadows, Hop-Gardens, Orangeries, Melon-Grounds, Vineyards, Orchards, Nurseries, Physick-Gardens, Warrens, Paddocks of Deer, Sheep, Cows, &c. with the rural Enrichments of Hay-Stacks, Wood-Piles, &c.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, Cyclopaedia (2:n.p.) [10]

- “ORANGERY, a gallery in a garden, or parterre, exposed to the south, but well closed with a glass window, to preserve oranges in, during the winter season. The orangery of Versailles is the most magnificent that ever was built: It has wings, and is decorated with a Tuscan order.

- “ORANGERY is also used for the parterre, where the oranges are exposed in kindly weather.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (2:n.p.) [11]

- “O’RANGERY. n.s. [orangerie, Fr.] Plantation of oranges.”

- Loudon, J. C., 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 811–14) [12]

- “6161. The hot-houses of floriculture are the frame, glasscase, green-house, orangery, conservatory, dry-stove, the bark or moist stove, in the flower-garden, or pleasure-ground; and the pit and hot-bed in the reserve-garden. In the construction of all of these the great object is, or ought to be, the admission of light and the power of applying artificial heat with the least labor and expense. ...

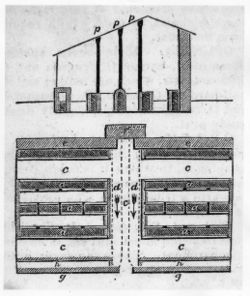

- “6171. The orangery is the green-house of the last century, the object of which was to preserve large plants of exotic evergreens during winter, such as the orange tribe, myrtles, sweet bays, pomegranates, and a few others. . . . The orangery was generally placed near to or adjoining the house, and its elevation corresponded in architectural design with that of the mansion. From this last circumstance has arisen a prejudice highly unfavorable to the culture of ornamental exotics, namely, that every plant-habitation attached to a mansion should be an architectural object, and consist of windows between stone piers or columns, with a regular cornice and entablature. By this mode of design, these buildings are rendered so gloomy as never to present a vigorous vegetation, and vivid glowing colors within; and as they are thus unfit for the purpose for which they are intended, it does not appear to us, as we have already observed at length (1590.), that they can possibly be in good taste. Perhaps the only way of reconciling the adoption of such apartments with good sense, is to consider them as lounges or promenade scenes for recreation in unfavorable weather, or for use during fêtes, in either of which cases they may be decorated with a few scattered tubs of orange-trees, camellias, or other evergreen coriaceous-leaved plants from a proper greenhouse, and which will not be much injured by a temporary residence in such places, which, as Nicol has observed, ‘often look more like tombs or places of worship, than compartments for the reception of plants; and, we may add that the more modern sort look like a combination of shop-fronts, of which that at Claremont is a notable example.’ Sometimes structures of this sort are erected to conceal some local deformity, of which, as an instance, we may refer to that . . . erected by Todd, for J. Elliot, Esq., at Pimlico. ‘This building was constructed for the purpose of preventing the prospect of some offices from the dwelling-house. The architectural ornaments, and the roof, not being of glass, are points in the construction not generally to be recommended; but, as it was built for the purpose above mentioned, the objections were overruled. There are three circular stages to this house, which are made to take out at pleasure. The ceiling forms part of a circle, and the floor is paved with Yorkshire stone. It is fifty feet long, and thirteen feet six inches wide, and heated by one fire, the flue from which makes the circuit of the house under the floor.’ (Plans of Green-Houses, &c. p. 10)” [Fig. 9]

- Loudon, Jane, 1845, Gardening for Ladies (pp. 302–3) [13]

- “ORANGERY.—A house intended only for Orange trees may be opaque at the back, and even the roof, with lights only in front, provided the plants be set out during summer. In fact, so that the plants are preserved from the frost, they will do with scarcely any light during winter; and in many parts of the Continent, they are kept in a cellar.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (p. 404) [14]

- “ORANGERY is a green-house or conservatory devoted to the cultivation of the genus Citrus. The best plan for the construction of such a building is that erected at Knowsley Park, and thus described by the gardener, Mr. J. W. Jones. . . . [Fig. 10]

- “‘Measured inside, this house is fourteen and a half yards long, eight broad, and six high. In the centre of the house are eight borders, in which the oranges, &c., are planted; these borders are all marked a. The two borders against the back wall are sixteen inches broad, and three feet deep. The six borders immediately in the centre of the house are fourteen inches broad, and three feet deep; the paths are marked c, the front wall d, and the back one e; p, p, p, represent ornamental cast iron pillars, which, besides supporting the roof, serve also to support light wire trellises; there is one of these pillars in each row for each rafter. The house is entirely heated by smoke flues, two furnaces being placed at f. The dotted lines along the central path show the direction of the flues beneath, from the back to the front entrance, when they diverge, the one entering a raised flue, g, on the right, the other also entering a raised flue on the left. These flues again cross the house at each end, and the smoke escapes by the back wall; it being found inconvenient to place the furnaces in any other situation.

- “‘Two stoves immediately connected with each end of the orangery contain the collection of tropical plants bearing fruit. The communication between these stoves and the orangery is uninterrupted by any glass or other division, so that the orange tribe are subjected to nearly as high a temperature as the tropical plants. The central borders of the orangery, as may be seen in the section, are raised a little above each other, as they recede from the front of the house. The oranges, citrons, &c., are all trained as espaliers; a light wire trellis being stretched from pillar to pillar parallel with the borders, and about eight feet high. The spaces, b, between the borders being about three feet wide, permit a person to walk along between the plants, for the purpose of pruning, watering, &c. These spaces are of the same depth as the borders, and were originally filled with tan; but part of this is now removed, and its place is filled with good soil. In this some fine climbing plants have been turned out, amongst which are several plants of Passiflora quadrangularis, which bear an abundant crop of fine fruit. Besides these, there are also two fine plants of the beautiful new Gardenia Sherbourniae. These, are other climbers, are trained up the rafters, &c., in such a manner as not to materially intercept the light from the orange. The great advantage of having the trees trained on the trellis system is, that every part of the tree is fully exposed to the light, and by planting them in rows one behind the other, a larger surface is obtained for the trees to cover than could be got by adopting any other plan; and consequently, for the space, a larger quantity of fruit is procured. The trees being hung loosely and irregularly to the wires, assume as natural an appearance as circumstances will permit, and the introduction here and there of large plants in pots has a tendency to prevent formality. Two plants are placed in each border.’—Gard. Chron.”

- Webster, Noah, 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language (p. 776) [15]

- “OR’AN-GER-Y, n. [Fr. orangerie.]

- “A place for raising oranges; a plantation of orange-trees.”

Images

Inscribed

J. C. Loudon, Orangery at Pimlico, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), p. 813, fig. 570.

J. C. Loudon, Section and plan for a building to house orange trees, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1834), p. 974, fig. 785a and b.

J. C. Loudon, Orangery at Baden Gardens, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1834), p. 174, fig. 130.

J. C. Loudon, Plan of farmyard, garden offices and hot-houses at Cheshunt Cottage, in The Gardener's Magazine 15, no. 117 (December 1839): p. 642, fig. 159.

Associated

J. C. Loudon, "General View of the Hot-houses, as seen across the American Garden," Cheshunt Cottage, in The Gardener's Magazine, and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 15, no. 117 (December 1839): p. 646, fig. 161.

Attributed

Notes

- ↑ Anne Yentsch, “The Calvert Orangery in Annapolis, Maryland: A Horticultural Symbol of Power and Prestige in an Early Eighteenth Century Community,” in Earth Patterns: Essays in Landscape Archaeology, ed. William M. Kelso and Rachel Most (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1990), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Carmen A. Weber, “The Greenhouse Effect: Gender-Related Traditions in Eighteenth-Century Gardening,” in Landscape Archaeology: Reading and Interpreting the American Historical Landscape, ed. Rebecca Yamin and Karen Bescherer Metheny (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996), 49, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alice B. Lockwood, ed., Gardens of Colony and State: Gardens and Gardeners of the American Colonies and of the Republic before 1840, 2 vols (New York: Charles Scribner’s for the Garden Club of America, 1931), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bartram, Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, ed. by Mark Van Doren (New York: Dover, 1928), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. Loudon, "Descriptive Notices of Select Suburban Residences, with Remarks on Each; Intended to Illustrate the Principles and Practices of Landscape-Gardening," The Gardener's Magazine and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement XV, no. 117 (December 1839): 633–74, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th edn (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jean de La Quintinie, The Compleat Gard’ner, or Directions for Cultivating and Right Ordering of Fruit-Gardens and Kitchen Gardens, trans. by John Evelyn (New York: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Bradley, New Improvements of Planting and Gardening, Both Philosophical and Practical; Explaining the Motion of the Sapp and Generation of Plants. With Other Discoveries Never before Made in Publick, for the Improvement of Forest-Trees, Flower-Gardens or Parterres; with a New Invention Where by More Designs of Garden Platts May Be Made in an Hour, than Can Be Found in All the Books Now Extant. Likewise Several Rare Secrets for the Improvement of Fruit-Trees, Kitchen-Gardens, and Green-House Plants., 3rd edn, 2 vols (London: W. Mears, 1719), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Batty Langley, New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c. (Originally published London: A. Bettesworth and J. Batley, etc., 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . ., 5th edn, 2 vols (London: D. Midwinter et al, 1741), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th edn (London: Longman et al, 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden, ed. by A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. by David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language... Revised and Enlarged by Chauncey A. Goodrich.... (Springfield, Mass.: George and Charles Merriam, 1848), view on Zotero.