Difference between revisions of "Washington Square (Philadelphia, PA)"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

[[File:0901.jpg|thumbnail|Fig. 3, George Bridport, “Alternative designs for Washington Monument, Washington Square, Philadelphia,” 1816.]] | [[File:0901.jpg|thumbnail|Fig. 3, George Bridport, “Alternative designs for Washington Monument, Washington Square, Philadelphia,” 1816.]] | ||

| − | By 1794, Philadelphia’s municipal councils determined to improve Southeast Square by removing the [[burying ground]], enclosing the site with a border [[fence]], and planting Lombardy poplars.<ref>''Cultural Landscape Report'' 2010, 1.19, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/H4XK5UWA view on Zotero]. See also the entry for “Trees” in ''The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia'', which highlights the importance of the Lombardy poplar as one of George Washington’s favorite trees, <http://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/trees-2 | + | By 1794, Philadelphia’s municipal councils determined to improve Southeast Square by removing the [[burying ground]], enclosing the site with a border [[fence]], and planting Lombardy poplars.<ref>''Cultural Landscape Report'' 2010, 1.19, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/H4XK5UWA view on Zotero]. See also the entry for “Trees” in ''The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia'', which highlights the importance of the Lombardy poplar as one of George Washington’s favorite trees, <ref>See [http://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/trees-2].</ref> Though no longer used for burials, the site continued to be used for livestock, with a cattle market operating on the west side of the square between 1797 and 1815.<ref>''Cultural Landscape Report'' 2010, 1.20, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/H4XK5UWA view on Zotero].</ref> In 1815 and 1816, the Select and Common Councils appointed a committee to oversee improvements to Philadelphia’s squares and proposed renaming its four smaller squares in honor of celebrated Americans. This led to George Bridport’s 1816 plan for the site, which was renamed Washington Square in honor of the United States’ first president [Fig. 2].<ref>Elizabeth Milroy, “Repairing the Myth and the Reality of Philadelphia’s Public Squares, 1800–1850,” ''Change Over Time'' 1:1 (Spring 2011): 63, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/4VUAK4JG view on Zotero]. Southeast Square was known as Washington Square as early as 1818, but it was not officially renamed until 1825.</ref> Bridport, a London-born, Philadelphia-based artist and architect, developed a plan for the site featuring two circular [[promenade|promenades]] and a central plaza to accommodate a memorial to George Washington, for which the Society of the Cincinnati had begun to solicit funds as early as 1810.<ref>''Cultural Landscape Report'' 2010, 1.35, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/H4XK5UWA view on Zotero]. Numerous advertisements in the ''Democratic Press'', ''Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser'', and ''Relfs Philadelphia Gazette'' began to appear in 1810, announcing a lottery to raise funds for the Washington monument.</ref> Bridport developed two separate designs for the proposed monument: the first a domed [[temple]] flanked by [[obelisk|obelisks]], and the second a figurative statue framed by an [[arch]] [Fig. 3]. The executed design for Washington Square differed somewhat from Bridport’s original plan, as shown in an 1843 map, though it retained a circular [[promenade]] [Fig. 4]. The monument to George Washington never came to fruition, despite the efforts of the Society of the Cincinnati and proposals by Bridport and others, including the sculptor Henrico Caucici and the architect William Strickland.<ref>Caucici proposed his model of an equestrian statue as the design for the Washington monument; see ''Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser'' (November 20, 1816), p. 3.</ref> |

[[File:0903.jpg|thumbnail|left|Fig. 4, M. Schmitz (artist), Thomas S. Sinclair (lithographer), John B. Colahan (surveyor), “Map of Washington Square, Philadelphia,” 1843.]] | [[File:0903.jpg|thumbnail|left|Fig. 4, M. Schmitz (artist), Thomas S. Sinclair (lithographer), John B. Colahan (surveyor), “Map of Washington Square, Philadelphia,” 1843.]] | ||

Revision as of 15:55, December 21, 2020

Washington Square, originally called Southeast Square, was one of five open spaces incorporated into William Penn’s original plan for the city of Philadelphia in 1683. It was primarily a grazing pasture and potter’s field—as well as an important site of both celebration and mourning for Philadelphia’s African American community—until 1794. In that year the city began to return the site to its original role as a public square, with the inclusion of walks and an extensive variety of trees. Philadelphia’s Select and Common Councils appointed a committee to oversee improvements to the city’s squares in 1815, and proposed renaming them in honor of celebrated Americans, with Southeast Square rechristened Washington Square in honor of the country’s first president.

Overview

Alternate Names: Southeast Square; Potter’s Field

Site Dates: 1682–present

Site Owner(s): City of Philadelphia; National Park Service

Associated People: Thomas Holme (d. 1695); George Bridport (1783–1819); George Vaux (1779–1836)

Location: Philadelphia, PA

Condition: extant

View on Google maps

History

The 1683 plan for the city of Philadelphia, devised by William Penn and his surveyor, Thomas Holme, featured five public squares—one in the city’s center, and one in each of its four quadrants—which were intended to preserve the health and well-being of “this greene country town” and its inhabitants [Fig. 1]. The Southeast Square, however, soon began to serve other purposes; as early as 1706 it was leased as grazing pasture and was also designated a burying ground for strangers and the poor, later serving as an interment site for Revolutionary War soldiers and victims of Philadelphia’s 1793 yellow fever epidemic. It also became an important locus for free and enslaved African Americans, who used the square as both a cemetery and a place of celebration.[1]

In 1738 the city’s municipal councils drafted an ordinance intended to suppress various “Tumultuous meetings” of Philadelphia’s African American community, which may have led to the relocation of their gatherings to Southeast Square.[2] In his Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, historian John Watson observed that “[i]t was the custom for the slave blacks, at the time of fairs and other great holidays, to go there to the number of one thousand . . . and hold their dances, dancing after the manner of their several nations in Africa, and speaking and singing in their native dialects.”[3] Due to the important role Southeast Square played for Black Philadelphians, many were understandably angered by attempts disturb the site, particularly by those intending to disinter bodies for anatomical study. The African American community developed a nightly patrol to prevent such exhumations, much to the frustration of Dr. William Shippen Jr., professor of medicine at the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania): “[T]he negroes have determined to watch all who are buried in the Potters field,” Shippen wrote. “[O]n Saturday night with the assistance of six invalids with muskets [the exhumers] beat off the negroes and obtained a corps. I lodged it in the Theater. The resolute impertinent blacks broke open ye house stole ye subject and reburied it.”[4]

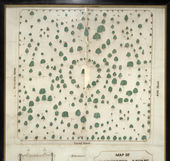

By 1794, Philadelphia’s municipal councils determined to improve Southeast Square by removing the burying ground, enclosing the site with a border fence, and planting Lombardy poplars.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag Though no longer used for burials, the site continued to be used for livestock, with a cattle market operating on the west side of the square between 1797 and 1815.[5] In 1815 and 1816, the Select and Common Councils appointed a committee to oversee improvements to Philadelphia’s squares and proposed renaming its four smaller squares in honor of celebrated Americans. This led to George Bridport’s 1816 plan for the site, which was renamed Washington Square in honor of the United States’ first president [Fig. 2].[6] Bridport, a London-born, Philadelphia-based artist and architect, developed a plan for the site featuring two circular promenades and a central plaza to accommodate a memorial to George Washington, for which the Society of the Cincinnati had begun to solicit funds as early as 1810.[7] Bridport developed two separate designs for the proposed monument: the first a domed temple flanked by obelisks, and the second a figurative statue framed by an arch [Fig. 3]. The executed design for Washington Square differed somewhat from Bridport’s original plan, as shown in an 1843 map, though it retained a circular promenade [Fig. 4]. The monument to George Washington never came to fruition, despite the efforts of the Society of the Cincinnati and proposals by Bridport and others, including the sculptor Henrico Caucici and the architect William Strickland.[8]

The layout of Bridport’s plan for Washington Square was overseen in 1816 and 1817 by George Vaux, a member of Philadelphia’s Common Council and the fourth President of the Horticultural Society of Pennsylvania, and the gardener Andrew Gillespie. Vaux’s papers identify sources for paving bricks, fencing, and trees, a number of which were purchased from Bartram’s Garden, including a wide array of maples, oaks, and poplars, among others.[9] The variety of trees in Washington Square carried great educational value, according to a report published on behalf of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society in 1831: “Hence instruction, with respect to our own productions, is placed before the public, and at the same time it is ascertained what trees are best acclimated to our own climate.”[10] Indeed, the number and variety of species planted at Washington Square led Andrew Jackson Downing to describe the site as a “really admirable city arboretum.”[11] A rare map dating to the second half of the 1830s highlights the different trees featured in the square [Fig. 5].

Although the 1816 redesign of Washington Square was intended to return it to its original purpose as a green space for an urban populace, including “those classes whose occupations are mechanical and sedentary,” it was initially accessible to the public only during the summer and autumn months.[12] By about 1825, however, it had become a year-round place of recreation and play, a site where children could “gambol and race over the smooth, clean, and shaded promenades” and fashionable couples could enjoy their evening peregrinations.[13] Although Washington Square underwent additional redesigns in 1881, 1913, and 1952, it continues to serve as a restorative natural site for Philadelphians.[14]

—Elizabeth Athens

Texts

- Shippen, William, Jr., December 18, 1787, in a letter to Thomas Lee Shippen[15]

- " . . . the negroes have determined to watch all who are buried in the Potters field. . . on Saturday night with the assistance of six invalids with muskets [the exhumers] beat off the negroes and obtained a corps. I lodged it in the Theater. The resolute impertinent blacks broke open ye house stole ye subject and reburied it.”

- Lane, Samuel, 1820, describing George Bridport’s proposal for Washington Square, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in O’Gorman et al. 1986: 68)[16]

- “[I am writing] to ascertain the artist who designed the public Garden on Chestnut Street [sic] at the place (if I am not mistaken) formerly called Potters field; and if he is in your town inquire if he would come on here [Washington, DC] to furnish a design for Improving the Capitol Square.”

- Trollope, Frances Milton, 1830, describing Washington Square, Philadelphia, PA (1832: 2:48–49)[17]

- “Near this enclosure [at the State House] is another of much the same description, called Washington Square. Here there was an excellent crop of clover; but as the trees are numerous, and highly beautiful, and several commodious seats are placed beneath their shade, it is, spite of the long grass, a very agreeable retreat from heat and dust. It was rarely, however, that I saw any of these seats occupied; the Americans have either no leisure, or no inclination for those moments of delassement that all other people, I believe, indulge in. . . it is nevertheless the nearest approach to a London square that is to be found in Philadelphia.”

- Trego, Charles, 1843, describing Philadelphia, PA (1843: 318–19)[18]

- “Public Squares.—It is to the wise and liberal foresight of the great founder of Pennsylvania that we owe most of the public squares which now ornament our city. In the original plan, as laid out by Thomas Holmes, Penn’s surveyor general in 1682, there was to be a public square in the centre containing ten acres, and one in each quarter of the city containing eight acres. . .

- “Washington square, on Sixth street between Walnut and Locust, was for many years used as a public burial ground for the poor and for strangers, under the name of the Potters’ field. . . Its improvement as a public square commenced in 1815, when a variety of trees were planted, gravel walks laid out, and other steps taken which have led to its present attractive appearance. It is intended to erect, in the centre of this square, a monument to the memory of Washington; the cornerstone having been laid with due ceremony at the celebration of his birth day, on the 22nd of February, 1833.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1850, describing public gardens (1850: 332–33)[19]

- “856. Public Gardens. . .

- “Promenade at Philadelphia. There is a very pretty enclosure before the walnut tree entrance to the state-house, with good well-kept gravel walks, and many beautiful flowering trees. It is laid down in grass, not in turf; which indeed, Mrs. Trollope observes, ‘is a luxury she never saw in America.’ Near this enclosure is another of a similar description, called Washington Square, which has numerous trees, with commodious seats placed beneath their shade.”

- Watson, John Fanning, 1857, describing Washington Square, Philadelphia, PA (1:405)[20]

- “This beautiful square, now so much the resort of citizens and strangers, as a promenade, was, only twenty-five years ago, a ‘Potter’s Field,’ . . . It was long enclosed in a post and rail fence, and always produced much grass.”

Images

George Bridport, “Design for Washington Monument, Washington Square, Philadelphia,” 1816.

George Bridport, “Alternative designs for Washington Monument, Washington Square, Philadelphia,” 1816.

Anonymous, “Map of Washington Square” [detail], c. 1835–40.

Anonymous, “Map of Washington Square” [detail], c. 1835–40.

M. Schmitz (artist), Thomas S. Sinclair (lithographer), John B. Colahan (surveyor), “Map of Washington Square, Philadelphia,” 1843.

Other Resources

Library of Congress Authority File

The Cultural Landscape Foundation

Washington Square (National Park Service)

Notes

- ↑ Bill Double, Philadelphia’s Washington Square (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2009), 8–9, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John F. Watson, Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, in the olden time; being a collection of memoirs, anecdotes, and incidents of the city and its inhabitants . . . , vol. 1 (Philadelphia: John Pennington and Uriah Hunt, 1844), 62, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Watson 1844, 1:406, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Shippen Jr. to Thomas Lee Shippen, December 18, 1787, quoted in Cultural Landscape Report for Washington Square (Philadelphia: U.S. Department of the Interior and National Park Service, September 2010), 2.19, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cultural Landscape Report 2010, 1.20, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Elizabeth Milroy, “Repairing the Myth and the Reality of Philadelphia’s Public Squares, 1800–1850,” Change Over Time 1:1 (Spring 2011): 63, view on Zotero. Southeast Square was known as Washington Square as early as 1818, but it was not officially renamed until 1825.

- ↑ Cultural Landscape Report 2010, 1.35, view on Zotero. Numerous advertisements in the Democratic Press, Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser, and Relfs Philadelphia Gazette began to appear in 1810, announcing a lottery to raise funds for the Washington monument.

- ↑ Caucici proposed his model of an equestrian statue as the design for the Washington monument; see Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser (November 20, 1816), p. 3.

- ↑ Cultural Landscape Report 2010, 1.40–42, view on Zotero. George Vaux’s papers are held by the Athenaeum of Philadelphia, located on the eastern edge of Washington Square.

- ↑ Report of the Committee appointed by the Horticultural Society of Pennsylvania for Visiting the Nurseries and Gardens in the Vicinity of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: W. Geddes, 1831), 15, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, Rural Essays (New York: George P. Putnam and Company, 1853), 305, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Letter to Senate, n.d., (c. 1816–24), quoted in Cultural Landscape Report 2010, 1.31, view on Zotero.

- ↑ National Gazette [Philadelphia] (June 1, 1830), p. 1.

- ↑ Cultural Landscape Report 2010, 2.25–28, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Quoted in Cultural Landscape Report 2010, 2.19, view on Zotero

- ↑ James F. O’Gorman et al., Drawing Toward Building: Philadelphia Architectural Graphics, 1732–1986 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press for the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1986), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans, 3rd ed., 2 vols. (London: Wittaker, Treacher, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles B. Trego, A Geography of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Edward C. Biddle, 1843), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed., corr. and improved (London: Longman et al., 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Fanning Watson, Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden Time; Being a Collection of Memoirs, Anecdotes, and Incidents of the City and Its Inhabitants, and of the Earliest Settlements of the Inland Part of Pennsylvania, from the Days of the Founders, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: E. Thomas, 1857), view on Zotero.