The Solitude

The Solitude, located on the west bank of the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, was the country estate of the Englishman John Penn. Greatly interested in eighteenth-century English architecture and landscape design, Penn created a small villa and picturesque landscape at his country retreat that many scholars credit with helping to spread neoclassicism in America. Today, the villa still stands on the grounds of the Philadelphia Zoo.

Overview

Alternate Names:

Site Dates: 1784–1788

Site Owner(s): John Penn (1760–1834)

Associated People:

Location: Philadelphia, PA

View on Google maps

History

Englishman John Penn (1760–1834), a grandson of Pennsylvania’s founder, William Penn (1644–1718), purchased fifteen acres of land on the west bank of the Schuylkill River from Isaac Warner in 1784 for a country house he named The Solitude (view text) [Fig. 1 - Birch painting].[1] The estate provided refuge from the hostile political climate Penn encountered in Philadelphia the previous year, when he traveled from London to request compensation from the Pennsylvania assembly for family property seized during the American Revolution.[2] Jude Collin Gleason has argued that The Solitude’s location several miles outside of the city “allowed Penn to keep his finger on the political pulse of Philadelphia, while keeping a safe distance from unfriendly factions.”[3] One nineteenth-century commentator described The Solitude as “a small house, just big enough for a bachelor and costly enough for a poet.”[4] Penn did occasionally entertain such illustrious guests as George Washington (1732–1799), who recorded in his diary that he had dined at Penn’s estate following a meeting of the Constitutional Convention in 1787 (view text). In a 1785 letter to her husband, however, Rebecca Shoemaker (1730–1819), a resident of nearby Laurel Hill on the east bank of the Schuylkill, wrote that Penn was “living a most recluse life” at The Solitude and that he was “making it all a garden and has built a house in a most singular style” (view text).[5]

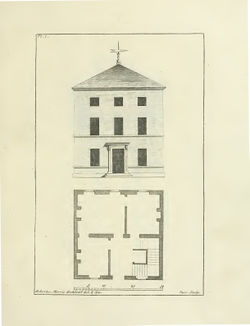

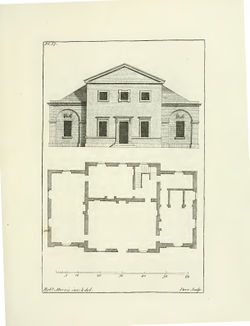

The house, which is still extant, is an early example of neoclassical architecture in Philadelphia and, as scholars have argued, likely played a significant role in the spread of neoclassicism in the United States.[6] Penn’s plans for The Solitude reveal his extensive knowledge of fashionable English neoclassical architecture and picturesque landscape design, and he was deeply involved in planning the villa.[7] His sketches of the floor plan, dated 1784, survive in Penn’s Commonplace Book at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.[8] Penn hired master builder William Roberts (d. 1808), who also likely contributed to the villa’s design.[9] The plan for the villa recalls characteristics of plates 1 and 37 in Robert Morris’s Select Architecture, a copy of which Penn owned.[10] Plate 1 of Morris’s text depicts the ground floor plan and front elevation of a small, thirty-foot cubic building, which may have inspired the overall shape and dimensions of Penn’s villa [Fig. 2].[11] The plan of the ground floor of Penn’s house, however, has more in common with the central bay of the structure depicted in plate 37, which Morris describes as “A little Building intended for Retirement, or for Study, to be placed in some agreeable Part of a Park or Garden” [Fig. 3].[12]

If the ground floor was somewhat derivative of Morris’ designs, scholars see a radical departure in the complex shapes and arrangement of the rooms on the upper two floors.[13] On the second story, for example, Penn’s library, a bedroom, and two smaller rooms (one with a sleeping alcove and the other with built-in cupboards) were arranged without axial symmetry and connected by various indirect passageways, which allowed for the “mediati[on] of public and private spaces” and enabled servants to navigate around rooms occupied by Penn or his associates in order to minimize disruptions in tight quarters.[14] Similarly, a forty-one-foot brick cryptoporticus connected the villa with a second structure (no longer extant) to the west of the house—a 24’5” single-story square building that contained a kitchen and offices—and enabled servants to pass between the two unseen.[15] Such below-grade passageways, drawing on the ancient example of the cryptoporticus commonly used in Roman villas, were often built at eighteenth-century English villas located along the banks of the Thames River. English poet Alexander Pope (1688–1744), for example, constructed an underground passageway to connect the basement of his villa in Twickenham with his extensive gardens.[16]

Texts

- Penn, John, date unknown, entry in his Commonplace Book, Historical Society of Pennsylvania (quoted in Westcott 1877: 438–439)[17] back up to history

- "I felt indeed the accustomed amor patriae and admiration of England, but sometimes a republican enthusiasm which attached me to America and almost tempted me to stay. . . . Earlier in the year I had made a dear purchase of fifteen acres, costing £600 sterling, and on the banks of the Schuylkill. I named it, from the Duke of Wurtemberg's, The Solitude—a name vastly more characteristic of my place. Advancing my house, I gradually altered my scheme to the great increase of the expenses it put me to. I might be in part actuated in this by a motive now grown stronger, the vanity of English taste in furnishing and decorating the house; and thought the money less thrown away as I then purposed keeping a house in the country, either for my agent to wait my return to the old country should my affairs require it."

- Penn, John, date unknown, entry in his Commonplace Book, Historical Society of Pennsylvania (quoted in Gleason 2002: 92)[18]

- "Before I read the marquis d'Lamenoiselle's excellent treatise on landscape, I find similar sentiment to one of his in my letter (date April 1783) to W. Gould. He recommends a proportion to be observed between the mansion and extent of prospect; a precept I have studiously followed, without knowing it, both in practice, at the Solitude & in theory in this extract from the letter [to W. Gould]."

- Shoemaker, Rebecca, May 23, 1785, in a letter from Philadelphia to Samuel Shoemaker in London, describing The Solitude (quoted in Gleason 2002: 36)[19] back up to history

- "He lives a most recluse life over Schuylkill. He bought about twenty acres of land and is making it all a garden and has built a house in a most singular style."

- Washington, George, July 19, 1787, diary entry describing The Solitude, estate of John Penn, near Philadelphia[20] back up to history

- "Dined (after coming out of Convention) at Mr. John Penn the youngers. Drank Tea & spent the evening at my lodgings."

- Penn, John, August 8, 1788, in a letter from London to Edmund Physick in Philadelphia (quoted in Gleason 2002: 94)[21]

- "[The Solitude is] a place which made my stay in a distant country, so full of trouble & anxiety, more tolerable to me."

- Physick, Edmund, December 12, 1789, in a letter from Philadelphia to John Penn in London, describing damage to The Solitude caused by a storm on July 5, 1789 (quoted in Gleason 2002: 90–91)[22]

- "The very heavy falls of water ran over the road with such force as to carry along with it as much gravel off the walks, into the gully & river (exclusive of common dirt) as has taken seventeen wagon loads to replace. The several of the stones placed near the Bridge to resemble natural rocks were undermined, the earth being washed from under them, the bridge was injured, and the water flounced down the gully with such great rapidity and violence as to deepen it three feet below the foundation of the wall you had laid for supporting the bank, the stone wall diving your land from Boltons was in many places washed down, almost all the land was removed out of the garden walks and thrown up in great ridges and piles over the beds so as to alter the whole form of the garden, these disagreeable effect having happened, my wife proceeded to get such repairs made as were most necessary, leaving some stone work under the planted stones in the gully unfinished, until we can be favored with your thoughts upon it."

- Birch, William Russell, 1808, The Country Seats of the United States of North America (1808: unpaginated)[23]

- "Here a pleasing solitude at once speaks the propriety of its title. Upon further research the solitary rocks, and the waters of the Schuylkill add sublimity to quietness. The house is built with great taste for a bachelor, by the former Governor John Penn, since the revolution."

Images

Other Resources

The Solitude - Philadelphia Zoo

Notes

- ↑ Penn named his estate after the Duke of Württemberg’s country palace in Stuttgart, La Solitude (built 1763–c. 1769), which Penn had visited during a Grand Tour in 1782–1783. Jude Collin Gleason argues that, La Solitude, as well as another of the Duke of Württemberg’s palaces visited by Penn—Monrepos (1760–1764) near Ludwigsburg—are two very early examples of French neoclassicism in Germany. Gleason, “A House in the Most Singular Style: John Penn’s The Solitude” (Master of Arts Thesis, University of Delaware, 2002), 12–13, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Penn inherited three-fourths of the family’s proprietary rights and property in Pennsylvania after the death of his father, Thomas Penn (1702–1775). The remaining one-fourth belonged to Penn’s older cousin, also named John Penn (1729&nash;1795), who was from Philadelphia and resided at his country estate Lansdowne, located just northwest of The Solitude. Ibid., 2, 17, view on Zotero; Thompson Westcott, The Historic Mansions and Buildings of Philadelphia, with Some Notice of Their Owners and Occupants (Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1877), 437, view on Zotero; Elizabeth Milroy, The Grid and the River: Philadelphia’s Green Places, 1682–1876 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016), 109, view on Zotero; Lorett Treese, The Storm Gathering: The Penn Family and the American Revolution (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992), 195–197, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gleason 2002, 21, view on Zotero. The decision may also have been driven by family considerations, providing Penn with an alternative to staying at Lansdowne. Ibid., 19–20.

- ↑ Westcott 1877, 440, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Rebecca Rawle and her second husband, Samuel Shoemaker, constructed a house at Laurel Hill in 1767, and the property remained in the Rawle-Shoemaker family until 1828. Roger W. Moss, Historic Houses of Philadelphia: A Tour of the Region’s Museum Homes (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press for The Barra Foundation, 1998), 98–99, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gleason 2002, 24, xi, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ibid., 18, view on Zotero. Born into a wealthy aristocratic family, Penn was well-educated and well-traveled, and he was heralded by contemporaries as an intellectual and a poet. Penn was the son of Thomas Penn and Lady Juliana Fermor, the daughter of the Earl of Pomfret, and he was educated at Eaton and the University of Cambridge. As a young man, Penn traveled throughout Europe, visiting his mother in Geneva in 1781 and undertaking a Grand Tour in 1782. Westcott 1877, 437, view on Zotero; Gleason 2002, 5, view on Zotero; Milroy 2016, 109, view on Zotero; Frances Fergusson, “James Wyatt and John Penn: Architect and Patron at Stoke Park, Buckinghamshire,” Architectural History 20 (1977): 45, view on Zotero. According to Gleason, Penn’s library contained three, “somewhat outmoded” architectural texts: Abraham Swan’s The British Architect, Batty Langley’s The Builder’s Compleat Assistant, and Robert Morris’s Select Architecture (1757). These texts served as important references for “practical solutions in designing a house,” but Penn relied on an “education in architecture” that “had been achieved through his elite upbringing in the first circles of England, and his extensive travels on the Continent.” Gleason 2002, 25, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fergusson 1977, 46, view on Zotero.

- ↑ According to Gleason, “Roberts’s working knowledge and Penn’s firsthand experiences with the most current European architectural styles likely allowed a degree of collaboration between builder and patron.” Gleason 2002, 25, view on Zotero. Roberts had also worked on the construction of Penn’s cousin’s nearby estate, Lansdowne. Ibid., 22–24. Gleason’s thesis names many of the artisans (masons, plasterers, painters, wood carvers, stone carvers, blacksmiths, and cabinetmakers) that Penn employed for the construction of The Solitude. Several of these contractors also worked at Lansdowne. Ibid., 37, 39–55.

- ↑ Penn owned a copy of the 1757 edition. Ibid., 28, view on Zotero.

- ↑ The Solitude is cubic in form and both Gleason and Moss report that the house’s dimensions are twenty-nine feet square. See Gleason 2002, 28, view on Zotero; Moss 1998, 69, view on Zotero. However, Westcott claims that the house is twenty-six feet long on each side. Westcott 1877, 441, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Morris, Select Architecture: Being Regular Designs of Plans and Elevations Well suited to both Town and Country; in which The Magnificence and Beauty, the Purity and Simplicity of Designing For every Species of that Noble Art, Is accurately treated, and with great Variety exemplified, From the Plain Town-House to the Stately Hotel, And in the Country from the genteel and convenient Farm-House to the Parochial Church, With Suitable Embellishments (London: Robert Sayer, 1755), 6, view on Zotero. For a description of Plate 1, see p. 1. See also Gleason 2002, 29–30, view on Zotero; Moss 1998, 69, view on Zotero. The plan of the ground floor, which features an entry hall and a parlor that doubled as a dining room, is also similar to floor plans employed at nearby Schuylkill River estates, such as Laurel Hill. Gleason 2002, 31, view on Zotero.

- ↑ According to Gleason, the plan exhibited principles of “novelty and variety” promoted by English architects Robert and James Adam in their Works in Architecture (1773) but also reflected the influence of eighteenth-century French architectural design. Pioneering developments in French planning reached the English through the published works of Jacques-Francois Blondel (1705–1774), Pierre Patte (1723–1814), and Jean-François de Neufforge (1714–1791), but Penn may also have seen examples when he lived with his mother in Paris in 1783. Gleason 2002, 31–32, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ibid., 34, view on Zotero. For a detailed description of the layout of the second and third floors, see p. 26–28.

- ↑ Penn had constructed this smaller structure first and lived there while the main house was being built, although he continued to entertain there even after the main house was completed. The building was demolished sometime between about 1874 and 1879, when the Philadelphia Zoo constructed a mammal house on the site. Ibid., 37, 36n62, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ibid., 36–37, 39–40, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Westcott 1877, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gleason 2002, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel and Rebecca Shoemaker Diaries, vol. 2, p. 208, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; quoted in Gleason 2002, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Washington Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Penn-Physick Manuscripts, vol. 1, p. 195, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; quoted in Gleason 2002, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Penn-Physick Correspondence, vol. 3, p. 254, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; quoted in Gleason 2002, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Russell Birch, The Country Seats of the United States, ed. by Emily T. Cooperman (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 58, view on Zotero.