Monticello

[http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/research/casva/research-projects.html A Project of the National Gallery of Art, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts ]

Overview

Site Dates: Established 1730s

Site Owner(s): Peter Jefferson (1707/8–1757), Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), Martha Jefferson Randolph (1772–1836) and children, James T. Barclay (1807–1874), Uriah P. Levy (1792–1862), Jefferson Monroe Levy (1852–1924), Thomas Jefferson Foundation

Associated People: Robert Bailey (gardener from 1794–1796), Wormley Hughes (1781–1858; enslaved gardener), Anne Cary Randolph (1791–1826)

Location: Charlottesville, Va.

View on Google maps

History

Texts

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1771, describing Monticello (1944: 26–27)[1]

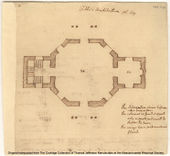

- “afew feet below the spring level the ground 40 or 50 f. sq. let the water fall from the spring in the upper level over a terrace in the form of a cascade. then conduct it along the foot of the terrace to the Western side of the level, where it may fall into a cistern under a temple, from which it may go off by the western border till it falls over another terrace at the Northern or lower side. let the temple be raised 2. f. for the first floor of stone. under this is the cistern, which may be a bath or anything else. the 1st story arches on three sides; the back or western side being close because the hill there comes down, and also to carry up stairs on the outside. the 2d story to have a door on one side, a spacious window in each of the other sides, the rooms each 8. f. cube; with a small table and a couple of chairs. the roof may be Chinese, Grecian, or in the taste of the Lantern of Demosthenes at Athens. . . .

- "the ground above the spring being very steep, dig into the hill and form a cave or grotto. build up the sides and arch with stiff clay. cover this with moss. spangle it with translucent pebbles from Hanovertown, and beautiful shells from the shore at Burwell's ferry. pave the floor with pebbles. let the spring enter at a corner of the grotto, pretty high up the side, and trickle down, or fall by a spout into a basin, from which it may pass off through the grotto. the figure will be better placed in this. form a couch of moss. the English inscription will then be proper.

- Nymph of the grot, these sacred springs I keep,

- And to the murmur of these waters sleep;

- Ah! spare my slumbers! gently tread the cave!

- And drink in silence, or in silence lave!"

- Jefferson, Thomas, c. 1804, describing the improvements of Monticello (Massachusetts Historical Society, Coolidge Collection)

- “The north side of Monticello . . . and all Montalto above the thoroughfare to be converted into park & riding grounds, connected at the thoroughfare by a bridge, open, under which the public road may be made to pass so as not to cut off the communication between the lower & upper park grounds.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1804, describing Monticello (quoted in Nichols and Griswold 1978: 111)[2]

- “The kitchen garden is not the place for ornaments of this kind. bowers and treillages suit that better, & these temples will be better disposed in the pleasure grounds.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1804, describing improvements for Monticello (quoted in Nichols and Griswold 1978: 111)[2]

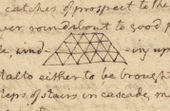

- “The ground between the upper and lower roundabouts to be laid out in lawns & clumps of trees, the lawns opening so as to give advantageous catches of prospect to the upper roundabout.. . .

- “The canvas at large must be Grove, of the largest trees, (poplar, oak, elm, maple, ash, hickory, chestnut, Linden, Weymouth pine, sycamore) trimmed very high, so as to give it the appearance of open ground, yet not so far apart but that they may cover the ground with close shade.

- “This must be broken by clumps of thicket, as the open grounds of the English are broken by clumps of trees. plants for thickets are broom, calycanthus, altheas, gelder rose, magnolia glauca, azalea, fringe tree, dogwood, red bud, wild crab, kalmia, mezereon, euonymous, halesia, quamoclid, rhododendron, oleander, service tree, lilac, honeysuckle, brambles.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, July 31, 1806, in a letter from Washington to William Hamilton[3]

- "having decisively made up my mind for retirement at the end of my present term, my views & attentions are all turned homewards. I have hitherto been engaged in my buildings, which will be finished in the course of the present year. the improvement of my grounds has been reserved for my occupation on my return home. for this reason it is that I put off to the fall of the year, after next the collection of such curious trees as will bear our winters in the open air. the grounds which I destine to improve in the style of the English gardens are chiefly in their native woods not a bush scarcely having been suffered to be cut out of them. it is easier to take away what is superfluous than to supply a chasm. are in a form very difficult to be managed. they compose the Northern quadrant of a mountain for about ⅔ of it’s height, & then spread for the upper third over it’s whole crown. they contain about 300. acres, washed at the foot, for about a mile, by a river of the size of the Schuylkill. the hill is generally too steep for direct ascent, but we make level walks successively along on it’s side, which in it’s upper part encircle the hill, & we intersect these again by others of easy ascent in various parts. they are chiefly still in their native woods, which are majestic, and very generally, a close undergrowth, which I have not suffered to be touched, knowing how much easier it is to cut away, than to fill up. the upper third is chiefly open, but to the South is covered with a dense thicket of [. . . .] (Cerastium supparium Lin.) which being favorably spread before the sun will admit of adventageous arrangement for winter enjoyment. you are sensible that this disposition of ground takes from me the first beauty in gardening, the variety of hill & dale, & leaves me as an awkward substitute a few hanging hollows & ridges. this subject is so original unique & at the same time refractory that to make a disposn analogous to it’s character, would require much more of the genius of the landscape painter & gardener than I pretend to: I had once hoped to get Parkins to go & give me some outline. but I was disappointed. certainly I could never wish your health to be such as to render travelling necessary: but should a journey at anytime promise improvement to it, there is no one on which you would be recieved with more pleasure than at Monticello should I be there. you would have an opportunity of indulging on a new field some of the taste which has made the Woodlands the only rival I have known in America to what may be seen in England. thither we are to go without doubt, for the first models in this art. their sun-less climate has permitted them to adopt what is certainly a beauty of the very first order in landscape. their canvas is of open ground, variegated with clumps of trees distributed with taste. they need no more of wood than will serve to embrace a lawn or a glade. but under the beaming, constant & almost vertical sun of Virga, shade is our Elysium. in the absence of this no beauty of the eye can be enjoyed. this organ then must yield it’s gratificn to that of the other senses, without the hope of any equivalent to the beauty relinquished. the only substitute I have been able to imagine is this. let your ground be covered with trees of the loftiest stature. trim up their bodies as high as the constitution & form of the tree will bear, but so as that their tops shall still unite and yield a dense shade. a wood, so open below, will have nearly the appearance of open grounds. then, where in open ground you would plant a clump of trees, place a thicket of shrubs presenting a hemisphere, the crown of which shall distinctly show itself under the branches of the trees. this may be effected by a due selection & arrangement of the shrubs, and will I think offer a groupe not much inferior to that of trees. the thickets may be varied too by making some of them of evergreens, altgether. our red cedar made to grow in a bush, ever green Privet, Hyacanthus, Kalmia, Scotch broom, either separately or an[. . . .] are proper for this purpose, would be elegant; it will not grow in my part of the country.

- "Of prospect I have a rich profusion and offering itself at every point of the compas, mountains distant & near, smooth & shaggy, single & in ridges, a little river hiding itself among the hills so as to shew in lagoons only, cultivated grounds, under the eye and two small villages. to prevent a satiety of this is the principal difficulty. it may be successively offered, & in separate different portions through vistas, or which will be better, between thickets so disposed as to serve for vistas, with the advantage of shifting the scenes as you advance on your way.

- "You will be sensible by this time of the truth of my informan that my views are turned so steadfastly homeward that the subject runs away with me whenever I get on it. I sat down to thank you for kindnesses recieved, & to bespeak permission to ask further contribns from your collection, & I have written you a treatise on gardening generally, in which, art lessons would come with more justice from you to me."

- Jefferson, Thomas, June 7, 1807, in a letter to his granddaughter, Anne Cary Randolph (quoted in Betts and Perkins 1986: 36)[4]

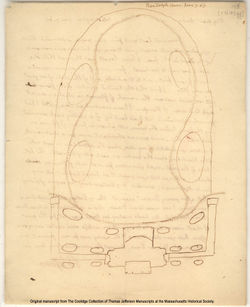

- "I find that the limited number of our flower beds will too much restrain the variety of flowers in which we might wish to indulge, and therefore I have resumed an idea . . . of a winding walk surrounding the lawn . . . with a narrow border of flowers on each side. . . . I enclose you a sketch of my idea, where the dotted lines on each side. . .shew the border on each side of the walk. The hollows of the walk would give room for oval beds of flowering shrubs." [Fig. y]

- Jefferson, Thomas, February 1, 1808, describing an experimental garden at Monticello (1944: 360)[1]

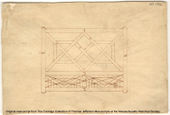

- “in all the open grounds on both sides of the 3d. & 4th. Roundabouts, lay off lots for the minor articles of husbandry, and for experimental culture, disposing them into a ferme ornée by interspersing occasionally the attributes of a garden.” [Fig. z]

- Jefferson, Thomas, March 1, 1808, in a letter from Washington to William Hamilton[5]

- "I am very thankful to you for thinking of me in the destination of some of your fine collection. within one year from this time I shall be retired to occupations of my own choice, among which the farm & garden will be conspicuous parts. my green house is only a piazza adjoining my study, because I mean it for nothing more than some oranges, Mimosa Farnesiane & a very few things of that kind. I remember to have been much taken with a plant in your green house, extremely odoriferous, and not large, perhaps 12. or 16. I. high if I recollect rightly. you said you would furnish me a plant or two of it when I should signify that I was ready for them. perhaps you may remember it from this circumstance, tho’ I have forgot the name. this I would ask for the next spring if we can find out what it was, and some seeds of the Mimosa Farnesiena or Nilotica. the Mimosa Julibrisin or silk tree you were so kind as to send me is now safe here, about 15. I. high. I shall carry it carefully to Monticello. I will not trouble you for the paper Mulberry mr Maine having supplied me with 12. or 15. which are now growing at Monticello."

- Jefferson, Thomas, March 1, 1808, in a letter to William Randolph, describing Monticello (1944: 366)[1]

- "my green house is only a piazza adjoining my study, because I mean it for nothing more than some oranges, Mimosa Farnesiana & a very few things of that kind. I remember to have been much taken with a plant in your green house, extremely odoriferous, and not large . . . (Jefferson Papers, L. C. [Library of Congress])."

- Smith, Margaret Bayard, August 1, 1809, describing Monticello (1906: 73)[6]

- “As we passed the graveyard, which is about half way down the mountain, in a sequestered spot, he told me he there meant to place a small gothic building,—higher up, where a beautiful little mound was covered with a grove of trees, he meant to place a monument to his friend Wythe.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, April 8, 1811, in a letter to Bernard M’Mahon (1944: 455)[1]

- “I have an extensive flower border, in which I am fond of placing handsome plants or fragrant. those of mere curiosity I do not aim at, having too many other cares to bestow more than a moderate attention to them. in this I have placed the seeds you were so kind as to send me last. in it I have also growing the fine tulips, hyacinths, tuberoses & Amaryllis you formerly sent me. my wants there are Anemones, Auriculas, Ranunculus, Crown Imperials & Carnations."

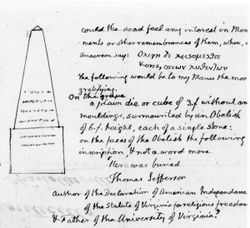

- Jefferson, Thomas, pre-1826, description of his own tombstone planned for Monticello (Massachusetts Historical Society, Coolidge Collection: K162)

- "On the grave a plain die or cube of 3 feet without any moldings, surmounted by an obelisk of 6 f. height, each of a single stone: on the face of the Obelisk the following inscription, and not a word more: Here was buried / Thomas Jefferson, / author of the Declaration of Independence / of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom / & Father of the University of Virginia because by these, as testimonials that I have lived, I [w]ish most to be remembered. to be of the coarse stone of which my columns are made, that no one might be tempted hereafter to destroy it for the value of the materials. my bust by Ciracchi, with the pedestal and truncated column on which it stands, might be given to the University if they would place it in the Dome room of the Rotunda. on the Die of the obelisk might be engraved Born Apr. 2. 1763.O.S. / Died___" [Fig. x]

- Loudon, J. C., 1850, describing Monticello (Loudon 1850: 331)[7]

- “849. Monticello, the seat of Jefferson, is situated on the summit of an eminence commanding extensive prospects on all sides.”

Images

Other Resources

Library of Congress Authority File

The Cultural Landscape Foundation

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. by Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Frederick Doveton Nichols and Ralph E. Griswold, Thomas Jefferson, Landscape Architect (Charlottesville, Va.: University Press of Virginia, 1978), view on Zotero

- ↑ Jefferson Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Edwin M. Betts and Hazlehurst Bolton Perkins, Thomas Jefferson’s Flower Garden at Monticello (Charlottesville, Va.: Thomas Jefferson Foundation, University of Virginia, 1986), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jefferson Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, ed. by Gaillard Hunt (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1906), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed., corr. and improved (London: Longman et al., 1850), view on Zotero.