Bethesda Orphan House

Overview

Site Dates: 1740–1741

Site Owner(s): George Whitefield 1714–1770; Selina, Lady Huntingdon 1707–1791; The State of Georgia;

Associated People: James Habersham, headmaster;

Location: Chatham County (near Savannah), GA · 31° 57' 32.00" N, 81° 5' 48.91" W

Keywords: Avenue; Bridge; Fence; Grove; Meadow; Orchard; Piazza; Plantation; Prospect; Thicket; View/Vista; Wilderness; Wood/Woods; Yard

The Bethesda Orphan House was founded by the English evangelist George Whitefield (1714–1770) in a cleared pine forest ten miles from Savannah, Georgia. His ambitious campus included a “great house” with a piazza, a well-stocked garden, and extensive fields initially worked by members of the orphanage and later by enslaved people.

History

The charismatic young preacher George Whitefield (1714–1770) journeyed from England to the recently founded colony of Georgia in 1738 with the expectation of advancing the evangelical movement in the New World—in part, through the creation of an orphanage, an idea that reportedly originated with Charles Wesley and James Oglethorpe.[1] Whitefield’s sermons stirred a fervent response during his brief stay in Savannah.[2] “The seed of the glorious gospel has taken root in the American ground,” he wrote to a friend in November 1738, “and, I hope, will grow up into a great tree.”[3] On his return to England, Whitefield used his increasingly popular itinerant preaching as a vehicle for drumming up philanthropic support for the orphanage he envisioned in Savannah.[4] By the time he returned to America in 1739, Whitefield was an international celebrity attracting enormous crowds. From Boston to Savannah, he delivered impassioned sermons that spawned thousands of converts. Deeply impressed, Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) became a lifelong friend and advocate. In addition to publishing many of Whitefield’s sermons and letters, he tried, unsuccessfully, to convince Whitefield to build his orphan house in Philadelphia, rather than the barely tamed wilderness of Georgia, where labor and materials were scarce.[5]

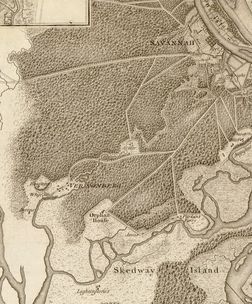

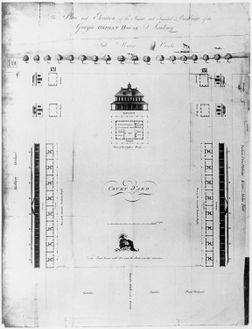

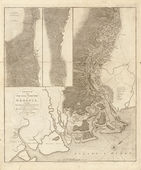

Having received a grant of 500 acres in Georgia, Whitefield entrusted the selection of a specific site for his orphanage to James Habersham, who had come from England in 1738 to serve as a school master.[6] Whitefield believed that a remote location would protect his charges from corrupting influences, and Habersham duly selected a pinewood forest ten miles from Savannah near the Vernon river, which he immediately began to clear for planting [Fig. 1]. Soon after returning to Georgia in January 1740, Whitefield made plans for buildings and other improvements that would allow the orphanage to become self-sustaining.[7] By December Whitefield had erected a fence-enclosed compound of several buildings, the most important of which was a sixteen-room “great house” built on elevated ground, with a ten-foot wide piazza wrapping around all four sides. Visitors would later remark on the convenience of the piazza as a sheltered walk in summer and winter. The front of the great house opened onto a large court yard, with a peach orchard and garden beyond [Fig. 2]. A walk through the middle of the garden led to an avenue that terminated in a twelve-mile road to Savannah that Whitefield had built, complete with several bridges—“a thing not before done since the province has been settled,” he was proud to note (view text).[8] While under construction, Whitefield’s Orphan House propped up Savannah’s struggling economy and was the largest civil employer in Georgia.[9]

Whitefield may have brought seeds and plants with him from England, because visitors noted a great variety of exotic vegetation in the Orphan House garden. Following a visit in 1743, the English writer Edward Kimber (1719–1769) asserted, “The Garden, which is a very extensive one, and well kept up, is one of the best I ever saw in America, and you may discover in it Plants and Fruits of almost every Clime and Kind” (view text). Five years later another English visitor described “a beautiful Garden and a fine Orchard containing allmost all Sorts of fruits, Trees, and Herbs which the country will afford,” as well as “Yards about 120 feet long, planted with orange Trees”(view text). In 1765 William Bartram found a “garden handsomely laid out and planted with oranges, pomegranates, figs, peaches, and other fruit trees”(view text). Maintenance of these plants was initially the responsibility of young girls at the Orphan House, whose “vacant Hours were employ’d in Garden and Plantation-Work.”[10] Among those tending the garden was the future Elizabeth Lamboll, who went on to create the first botanic garden in Charleston. By 1757 “a special gardener” had been hired to oversee the Bethesda garden.[11]

Whitefield hoped to develop the Orphan House into a “place of literature and academical studies,” and at various times spoke of creating a seminary for training pastors and a college for White, Black, and Native American children.[12] Believing that a large labor force was required to produce crops and commodities in support of this expanded mission, Whitefield became a staunch advocate of legalizing slavery in Georgia. By 1749 five “negros” were reportedly clearing land for a plantation, and in 1756 Johann Martin Boltzius (1703–1765), a German minister strongly opposed to slavery, observed thirty slaves working on Whitefield’s “Negro farm” a few miles from the orphanage.[13] Over the course of the next decade, Whitefield acquired additional land and slaves to work it.[14] Following his death in 1770, responsibility for the orphanage passed to Whitefield’s patron and heir, Selina, Countess of Huntingdon (1707–1791), who continued the work of recruiting teachers and missionaries, as well as acquiring slaves.

A fire caused by lightning destroyed Bethesda’s great house in 1773. Further damage resulted from pillaging and occupation by soldiers during the Revolution, followed by a hurricane and second fire in 1805.[15] By then, the institution was functioning as a school for children of the poor, supervised by the State of Georgia. In 1854 the Union Society purchased the property and built a new orphan house, once more combining residential care for parentless children with the mission of Christian education.[16] Today the 650-acre campus is home to the Bethesda Academy, a private boarding and day school for boys. The oldest child-care institution in the United States, the Bethesda Academy sustains Whitefield’s religious and educational mission, as well as his commitment to training children in land cultivation and stewardship, by offering work study programs at its organic farming facility and wildlife sanctuary and preserve.[17]

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Whitefield, George, January 20, 1740, journal entry describing preparations for Bethesda Orphan House (Henry 1957: 56)[18]

- “Went this Day with the Carpenter and Surveyor, and laid out the Ground whereon the Orphan-House is to be built. It is to be sixty Feet long, and forty wide. A Yard and Garden before and behind. The Foundation is to be Brick, and is to be sunk four Feet within, and raised three Feet above the Ground.—The House is to be two Story high, with an Hip-Roof: The first ten, the second nine Foot high.—In all, there will be near twenty commodious rooms.—Behind are to be two small Houses, the one for an Infirmary, the other for a Work-house. There is also to be a Still-House for the Apothecary. . . . There are near thirty working at the Plantation already, and I would employ as many more, if they were to be had.”

- Whitefield, George, December 23, 1740, “Account of the Affairs of the Orphan House in Georgia” (North 1914: 158-59)[19] back up to History

- “We are now all removed to Bethesda. We live in the outhouses at present; but in less than two months the great house will be finished so as to receive the whole family. It is now weather-boarded and shingled; and a piazza of ten feet wide is built all around it, which will be wonderfully convenient in the heat of summer. . . . There are no less than four framed houses, and a large stable and cart-house, besides the great house. In that, there will be sixteen commodious rooms, besides a large cellar of sixty feet long and forty wide. Near twenty acres of land are cleared round about it, and a large road made from Savannah to the Orphan House, twelve miles in length—a thing not before done since the province has been settled. . . . In a year or two, we hope to have a considerable quantity of fresh provisions for our family.”

- Habersham, James, June 11, 1741, letter from Charles-Town to George Whitefield (Whitefield 1771: 3:442)[20]

- “The garden and plantation now afford us many comfortable things, and in great plenty. . . . If GOD should so order it, that we should have a plantation in Carolina, as I believe he will bring to pass, we shall need but little, if any, assistance from abroad.”

- Habersham, James, March 24, 1741, letter to George Whitefield (Whitefield 1771: 3:445)[20]

- “As we have got so much land cleared, I intend to try to plant it; accordingly I have four or five hands, which, with our own household, will be sufficient to plant twenty acres or upwards with potatoes and rice for fodder next winter, having greatly suffered this, for want of it; likewise corn and pease, and other necessaries. Our garden is in great forwardness: we are like to have a crop of English pease.”

- Habersham, James, October 2, 1741, letter to George Whitefield (Whitefield 1771: 3: 445)[20]

- “Our garden is very fruitful of greens, turneps, &c. and we expect a good crop of potatoes.”

- Anonymous [“A young Gentleman of Boston”], letter from Bethesda to his father, January 1, 1742 (Whitefield 1771: 3:443–44)[20]

- “The Orphan-House is pleasantly situated, and, with the buildings belonging to it, presents a much handsomer prospect than is given by the draught annexed to the public accounts. The great house is now almost quite finished, and nothing has hindered but the want of glass . . . and some bricks. . . . It is surprising to see in what forwardness things are, considering what hindrances they have had, and the scarcity of labourers in this province. They have cut a fine road to Savannah of twelves miles length, through a thicket of woods; and, that it might be passable, were obliged to make ten bridges and cross-ways; which was done at no little charge. They have also cleared forty acres of land, twenty of which were planted the last year, and brought them to a tolerable crop; the other twenty was for the benefit of the air. They have also a large garden at the front of the house, brought into pretty good order.”

- Kimber, Edward, April 1744, describing Savannah and the Bethesda Orphan House (1998: 34)[21] back up to History

“We could not help observing, as we passed, several very pretty Plantations. Wormsloe is one of the most agreeable Spots I ever saw. . . . From this House there is a Vista of near three Miles, cut thro’ the Woods to Mr. Whitefield’s Orphan House, which has a very fine Effect on the Sight.

“The Route from Wormsloe to Mr. Whitefield’s Orphan-House is extremely agreeable, mostly thro’ Pine Groves, where we saw the recent Appearances of a Storm of Thunder and Lightning, that happened the Day before. . . .

“It gave me much Satisfaction to have an Opportunity to see this Orphan-House, as the Design had made such a Noise in Europe, and the very Being of such a Place was so much doubted every where, that even no farther from it than New England, Affadvits were made to the contrary. It is a square Building, of very large Dimensions, the Foundation of which is of Brick, with Chimneys of the same, the rest of the Superstructure of Wood; the Whole laid out in a neat and elegant Manner. A Kind of Piazza-Work surrounds it, which is a very pleasing Retreat in the Summer. The Hall, and all the Apartments are commodious, and prettily furnished. The Garden, which is a very extensive one, and well kept up, is one of the best I ever saw in America, and you may discover in it Plants and Fruits of almost every Clime and Kind. The Outhouses are convenient, and the Plantation will soon surpass almost any Thing in the Country. The Front is situated towards Mr. Jones’s Island . . . to whose Plantation the foremention’d Vista is clear’d, which affords to both Settlements a good Airing and Prospect.”

- Whitefield, George, March 21, 1746, “Continuation of the Account and Progress, &c. of the Orphan-House” (1771: 3:466–668)[20]

- “I called it Bethesda, because I hoped it would be a house of mercy to many souls. . . I am surprized when I look back, and see, how for these six years last past, GOD has spread a table in the wilderness for so many persons. . . We have lately begun to use the plow; and next year I hope to have many acres of good oats and barley. . . Our garden, which is very beautiful, furnishes us with all sorts of greens, &c. . . . If the vines hit, we may expect two or three hogsheads of wine out of the vineyard. . . . The Orphan-House, like the burning bush, has flourished unconsumed.”

- Fayrweather, Samuel, May 15, 1748, letter to Thomas Prince (Hawes 1961: 364)[22] back up to History

“The Orphan House . . . Stands on a Riseing Ground, having a Descent On all Sides,—On the North & South, are Yards about 120 feet long, planted with orange Trees. On the East, is a Water Passage to Carry You, to any part of Georgia, Carolina &c. it lyes Open for Severall Miles, and is Accounted Twelve Miles from the Sea. On the West (which is the front of the House) are four Small Houses Standing a proper Distance from the Great House, & from Each others, Above These, There is a beautiful Garden and a fine Orchard containing almost all Sorts of fruits, Trees, & Herbs which the country will afford. . . . [F]arther West . . . is Cutt an avenue about 25 Rod Board, In Length half a mile—Att the Head of which, is a wide River fit to carry a large Vessel to Sea, here likewise it is open for many Miles. On the North Side of this avenue, a Road begins to Savannah, which is Accounted Twelve Miles. There is from the Orphan House About forty Acres of Land Clear’d Twenty for the benefit of the air, the other Twenty for Planting . . . .

- “[The Orphan House] has a Piazza all around of 10 feet Broad, Near 20 feet high. It has four Ways to Go into, one on Every Side ascending with Six Steps.”

- Boltzius, Johann Martin, January 27, 1757, letter from Ebenezer, GA, describing a visit to the Bethesda Orphan House (Jones and Summer 2000: 288–91)[23]

“It lies twelve English miles distant from Savannah on a very bad and naturally infertile soil, where one finds neither good river nor well water. The ebb and flood tides almost reach the house . . . .

“A couple of years ago Mr. Whitefield received a good piece of land about three miles away, on which he has his Negro farm and where he has his Negroes plant grain, beans, sweet potatoes, rice, and indigo and saw boards and thin planks. He also has them fabricate roof shingles of cypress for sale to the West Indian merchants. On his new plantation he has perhaps more cypress than he wants (for such soil is useless for planting), He has some thirty Moorish slaves or Negroes, and he has a man and his wife as overseers. However, so far their work here has not brought in as much as is required for the maintenance of the orphanage The last time he was in Georgia and visited me in Ebenezer he had resolved to establish a new fund to buy a thousand pounds Sterling of Negroes and from the profit of their work to establish an academy at the orphanage. But now . . . nothing is to become of it. The orphanage is a large, beautiful building like a rich and noble castle about sixty foot long and sixty wide and two stories high. It has a very good and durable foundation of brick, a big walled cellar and next to it (also under the house) the kitchen, which is very comfortable in both winter and summer. The house is of wood and boards, paneled inside and painted with oil paint both inside and out . . . .

- There is little meadow land in the vicinity, and therefore butter and milk are rare here. From the garden, for which a special gardener is employed, they sometimes bring something green into the kitchen, but it is not worth the expense . . . .”

- Bartram, William, September 25, 1765, describing the Bethesda Orphan House (Jones Jr. 1883: 1:410)[24] back up to History

- “A neat brick Building well finished and painted both within and without: its dimensions 60 x 40 with cellaring all the way through, two stories high, with good garrets and a turret, and bell on the top. Piazzas ten feet wide project on every side, and form a pleasant walk both winter and summer round the house. . . . This celebrated building stands on an acre and a half, well fenced: one side of which fronts a salt water creek which is dry when the tide is out, but flows eight feet high when the tide rises. On the opposite side is a garden handsomely laid out and planted with oranges, pomegranates, figs, peaches, and other fruit trees, and at a small distance the school-house, stables, and other outbuildings are regularly disposed. To all this Mr. Whitefield has added a plantation well stocked with negroes for the use of a College.”

Images

Other Resources

Bethesda Academy Museum and Visitors Center website

Cheshunt Collection on Bethesda College, Georgia Historical Society

Samuel Fayrweather's account of Bethesda, 1748

Notes

- ↑ George Whitefield, “Continuation of the Account and Progress, &c. of the Orphan-House” (March 21, 1746) in The Works of the Reverend George Whitefield, M.A., . . . to Which Is Prefixed, an Account of His Life, Compiled from His Original Papers and Letters, 6 vols. (London: Edward and Charles Dilly, 1771), 3:463, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kidd, George Whitefield: America’s Spiritual Founding Father (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 45–50, 56, view on Zotero; Stuart Clark Henry, George Whitefield: Wayfaring Witness (New York: Abingdon Press, 1957), 35–41, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Whitefield to Mr. —, November 16, 1738, quoted in Kidd, 2014, 57, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kidd 2014, 66, 81, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kidd 2014, 84–85,view on Zotero; Eric McCoy North, Early Methodist Philanthropy (New York: The Author, 1914), 161–62, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward J. Cashin, Beloved Bethesda: A History of George Whitefield’s Home for Boys, 1740–2000 (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2001), 5, view on Zotero; Henry 1957, 55, view on Zotero; Thomas Gamble Jr., Bethesda, An Historical Sketch of Whitefield’s House of Mercy in Georgia, and of the Union Society, His Associate and Successor in Philanthropy (Savannah, GA: Morning News Print, 1902), 20–21, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cashin 2001, view on Zotero; Gamble 1902, 21, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Whitefield, “An Account of the Affairs of the Orphan House in Georgia,” December 23, 1740, in Eric McCoy North, Early Methodist Philanthropy (New York: The Author, 1914), 158, view on Zotero. See also Whitefield 1771, 3:465–67, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kidd 2014, 262, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Kimber, Itinerant Observations in America, ed. Kevin J. Hayes (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1998), 34, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Fenwick Jones, “A Letter by Pastor Johann Martin Boltzius About Bethesda and Marital Irregularities in Savannah,” The Georgia Historical Quarterly, 84 (2000): 291, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kidd 2014, 209, 239–41, view on Zotero; Gamble 1902, 42–46, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kidd 2014, 199–200, 209, 215, 238–39; see also 262, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Tara Leigh Babb, “‘Without A Few Negroes’: George Whitefield, James Habersham, and Bethesda Orphan House In the Story of Legalizing Slavery In Colonial Georgia” (master's thesis, University of South Carolina, 2013), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gamble 1902, 71–89, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cashin 2001, 163–64, view on Zotero; Charles Edgeworth Jones, “Education in Georgia,” Contributions to American Educational History 5 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1889), 15, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Information from Bethesda Academy website.

- ↑ Henry 1957, view on Zotero.

- ↑ North 1914, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Whitefield 1771, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Kimber, Itinerant Observations in America, ed. Kevin J. Hayes (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1998), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Fayrweather to Thomas Prince, May 25, 1748, quoted in Lilla Mills Hawes, “A Description of Whitefield’s Bethesda: Samuel Fayrweather to Thomas Prince and Thomas Foxcroft,” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 45 (December 1961): 364, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jones and Summer 2000, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Colcock Jones Jr., The History of Georgia: Aboriginal and Colonial Epochs, 2 vols. (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, & Co., 1883), view on Zotero.