Andrew Gentle

Andrew Gentle (active 1799–1841), a British-born seedsman and gardener, laid out and managed the Elgin Botanic Garden in New York City, where he also operated a commercial trade in seeds and plants.

History

By his own account, Andrew Gentle was “brought up to horticultural work, in all its departments.”[1] He was possibly a member of the Gentle family of Peebles, Scotland, proprietors of a multi-generational commercial practice as nursery- and seedsmen.[2] After managing “two very extensive establishments” in Britain for six years, Gentle immigrated to the United States, where, as he recorded in his book Every Man His Own Gardener (1841), he “commenced operations for Dr. Hosack, in New-York, by laying out his grounds” in 1805.[3] By “grounds,” Gentle presumably meant the twenty-acre botanic garden that Hosack, in his capacity as professor of botany and materia medica at Columbia College, was developing as a teaching aid [Fig. 1]. Hosack had purchased the property in 1801. By 1805 he had erected a conservatory and two hothouses for the collection of indigenous and exotic plants that he was assembling [Fig. 2]. As indicated by Gentle, the grounds had yet to be laid out, though Hosack promised readers of his Catalogue of Plants Contained in the Botanic Garden at Elgin (1806) that “The grounds will be arranged in a manner the best adapted to the different kinds of plants, and the whole enclosed by a belt of forest trees and shrubs, native and exotic.”[4]

It is unclear whether Andrew Gentle contributed to the design of the Elgin Botanic Garden, or if “laying out [the] grounds” referred only to implementing an existing plan. His knowledge of British landscape and garden design would have been an asset, but he faced practical difficulties in dealing with New York’s unfamiliar climate. “On making inquiries of those who followed the business, relative to the usual time of putting some crops in the ground,” he later recalled, “I was . . . firmly satisfied, that the ‘appointed times,’ observed by my fellow-labourers, were based on uncertainty, and of course induced repeated failure and great disappointment.” Dissatisfied with this ad hoc practice and the ill-suited advice of gardening books, Gentle “became thoroughly convinced that a most material deviation from their instructions must be adopted by the practical cultivator in this country, in order to crown his labours with success” (). The Elgin Botanic Garden became the field of practical experimentation that honed Gentle’s expertise in American horticulture.

The price of Gentle’s work at the Elgin Botanic Garden figured among a number of costs that exceeded David Hosack's expectations. In 1805 and again in 1806, Hosack appealed to the New York legislature for financial support, as “The expenses necessary to effect these improvements, especially in the cultivation and arrangement of the grounds, and in erecting the buildings, [were] greater than what I had anticipated.”[5] In order to help offset these expenses, Gentle for a time operated a commercial market at the garden in addition to maintaining botanical specimens for scientific study. In 1807 he published an advertisement clarifying that the Elgin Garden was not only intended for the edification of medical students, but could also provide citizens with “the best vegetables for the table,” along with “medicinal Herbs and Plants, and a large assortment of green and Hot House Plants” (view text).

Gentle may have left the garden prior to April 1809, when Frederick Pursh began a brief stint as gardener at Elgin, succeeded by Michael Dennison less than two years later.[6] Hosack turned to both Gentle and Pursh for their assistance in assessing the monetary value of the garden in January 1810, when financial necessity compelled him to offer it for sale to the New York legislature. Gentle’s estimate of $14,380.59 for the “indigenous and exotic plants, tools &c.” (view text) was over $1,700 higher than the estimate Pursh drew up with two nurserymen (view text), and perhaps reflects Gentle’s more intimate familiarity with the garden and its history. In March 1811 Hosack published Hortus Elgeninsis (1811), a revised and enlarged catalogue of the Elgin Botanic Garden. Although Gentle’s name had not appeared in the first version of the catalogue, published in 1806, Hosack now listed “Mr. Andrew Gentle, seedsman, of this city” among “several gentlemen in this country, distinguished for their taste and talents in this department of science” who were “among the contributors to this institution.” The impressive list of American horticulturists and botanists included Samuel Latham Mitchill, Bernard M’Mahon, William Darlington, and William Prince (view text). In 1813 Andrew Gentle (“Florist and Seedsman”) was one of only three seedsmen listed in Longworth’s American Almanac. Two years later, he and Michael Dennison were two of four seedsmen listed in the New York Directory (along with 53 gardeners and one nurseryman).”[7] In the latter year Gentle placed advertisements in the Evening Post, offering “a general assortment of kitchen, garden, [and] flower seeds,” adding that “Catalogues can be had at the store gratis” (view text).

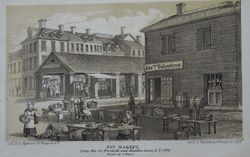

Gentle returned to the Elgin Botanic Garden in March 1817, leasing the property on an annual basis free of charge in exchange for maintaining the greenhouses and grounds.[8] The garden had declined over the past several years while it passed from the custody of the state legislature to the College of Physicians and Surgeons, to Columbia College. Increasingly concerned by its neglect, David Hosack was momentarily reassured by Gentle’s arrival on the scene. In a report read before the New York-Historical Society on April 8, 1817, Hosack noted the garden’s receipt of “a large collection” of European seeds from Thomas Jefferson and Monsieur [André] Thouin of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, adding: “Those seeds have all been conveyed to the Botanic Garden, where, in the hands of the present curator, Mr. Andrew Gentle, they will doubtless be cultivated with great care and fidelity.”[9] Gentle’s lease was renewed for several years during which he converted a portion of the grounds for agricultural use.[10] Years later he recalled, “In 1818 I had a piece of ground that had been under nursery for eight years, very rough and full of grass, had it turned over the middle of May, one half planted with the English white [potatoes], the other with the large flat blue sort.”[11] In advertisements that appeared in the New-York Evening Post from April 1817 to October 1820, Gentle offered seeds and plants for sale both at the Elgin Botanic Garden and at his shop near the Fly Market in lower Manhattan (the present-day Financial District) (view text) [Fig. 3].[12] Meanwhile, the scientific and educational function of the botanic garden had all but ceased, and in May 1819 the greenhouse plants along with “ornamental trees” and shrubs were transferred to the New York Hospital. Gentle’s lease had ended by 1823 when the grounds were rented to J. B. Driver for five years.[13]

When the Fly Market closed in 1821, Gentle relocated his shop to Fulton Market, while he and his family occupied a house a mile to the north on Chrystie Street.[14] The range of Gentle’s activities went well beyond that of seedsman. For example, in the spring of 1829, Adriance Van Brunt hired him to graft cherry trees.[15] By that time, Gentle was a noted authority on the management of American kitchen gardens. For a decade or more, he had been “strenuously advised to publish a work on useful Gardening,” but he refrained, having no knowledge of gardening practices in the American South (view text). It was only after visiting the southern states and analyzing the conditions there that he compiled the memoranda he had accumulated over the past twenty years and published Every Man His Own Gardener, borrowing the title from a well-known treatise of 1767 by the Scottish horticulturist John Abercrombie. Gentle provided his credentials on the title page of the book, noting that he was a member of the New York Horticultural Society and a corresponding member of the London Horticultural Society, although there is no evidence of his active participation in either group.[16] Ahead of these distinctions, he listed the affiliation of which he remained most proud, describing himself foremost as “Late Curator of the Elgin Botanic Garden, New-York.”

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Gentle, Andrew, June 4, 1807, Notice concerning the Elgin Botanic Garden, published in the New-York Commercial Advertiser (quoted in Stokes 1926: 5:1460–61)[17] back up to History

- “As it was the original design in forming this establishment to render it not only useful as a source of instruction to the students of medicine but beneficial to the public by the cultivation of those plants useful in diseases, by the introduction of foreign grasses, and by the cultivation of the best vegetables for the table; our citizens are now informed that they can be supplied with medicinal Herbs and Plants, and a large assortment of green and Hot House Plants etc.”

- Gentle, Andrew, January 22, 1810, “Valuation by Andrew Gentle, Botanist and Seedsman” of plants in the Elgin Botanic Garden (1811: 53–54)[18] back up to History

- “The sum of fourteen thousand three hundred and eighty dollars and fifty-nine cents, is, I believe, to the best of my judgment, the value of your indigenous and exotic plants, tools, & c. at Elgin.”

- Hastings, John, Frederick Pursh, and John Brown, January 24, 1810, Valuation of plants in the Elgin Botanic Garden (Hosack 1811: 53)[18] back up to History

- “We, the subscribers, in committee assembled, for the valuation of the plants, trees, and shrubs, including garden tools and utensils, necessary for the cultivation of the same, as appertaining to the green house, hot houses, and grounds of the botanic garden, at Elgin, after a very particular inventory and examination of the improvements, are unanimously agreed, that, to the best of our knowledge and ability, we consider them to be worth the sum of twelve thousand six hundred and thirty-five dollars and seventy-four and half cents.

- John Hastings, Nursery-man, Brooklyn, L.I.

- Frederick Pursh, Botanist.

- John Brown, Nursery-man.”

- Hosack, David, March 1811, revised and enlarged catalogue of the Elgin Botanic Garden (Hortus 1811: viii)[19] back up to History

- “Nor must I be unmindful of the obligations I am under to several gentlemen in this country, distinguished for their taste and talents in this department of science. The Hon. Robert R. Robert R. Livingston, our former Minister in France; Professor Mitchill, of this city; John Stevens, Esq. of Hoboken; Mr. Bernard M’Mahon, of Philadelphia; Mr. Stephen Elliot, of Beaufort, South-Carolina; Dr. Darlington, and Mr. John Vaughan, of Pennsylvania; John Le Conte, Esq. of Georgia; Mr. William Prince, of Long-Island; and Mr. Andrew Gentle, seedsman, of this city; are also among the contributors to this institution.”

- Gentle, Andrew, April 18 and 19, 1815, advertisement (New-York Evening Post)

- “ANDREW GENTLE, Seedsman. 103 Maiden-Lane. Catalogue of the seeds at the store gratis. . . . Enquire of Mr. Hall or at the Bar.”

- Gentle, Andrew, September 14, 1815, advertisement (New-York Evening Post) back up to History

- “. . . early York Cabbage . . . sugar loaf . . . Russian . . . Battersea . . . Scotch Drumhead . . . early and late Cauliflower. With a general assortment of kitchen, garden, flower seeds. Catalogues can be had at the store gratis, No. 124 Fly-Market. ANDREW GENTLE.”

- Hosack, David, April 8, 1817, Report read at a meeting of the Historical Society, New York (May 1817: 47)[20]

- “The Committee acknowledge with great pleasure, the reception of a large collection of seeds from Monsieur [André] Thouin, the Professor of Agriculture and Botany at the Jardin des Plantes, of Paris, and another from our learned countryman, Mr. [Thomas] Jefferson, as lately received by him from his European correspondents. Those seeds have all been conveyed to the Botanic Garden, where, in the hands of the present curator, Mr. Andrew Gentle, they will doubtless be cultivated with great care and fidelity.”

- Gentle, Andrew, October 1817, advertisement (New-York Evening Post) back up to History

- “BOTANIC GARDEN SEEDS AND PLANTS. For sale, by the subscriber, SEEDS, the growth of this year. Those wanting seeds to send to Europe will do well to apply, as they can be supplied with scarce and new species, on the most suitable terms. Also, a handsome collection of ornamental trees, plants in pots, and flowers, can be had daily during the ensuing winter. Apply to ANDREW GENTLE, at the Botanic Garden.”

- Gentle, Andrew, September 25, 1820, advertisement (New-York Evening Post)

- “SEEDS. THE GROWTH OF 1820. ANDREW GENTLE, from the Botanic Garden, informs his former customers and the public, that he has recommenced the seed business at the store, 155 Water-st., near the Fly Market, where Gardeners and Agriculturalists may depend on getting seeds genuine. . . .

- “A fine assortment of Bulbous Roots, Tulips, Hyacinths, &c. Double Camellias and other ornamental Plants. All kinds of implements for the garden, on the shortest notice, on the most reasonable terms.”

- Gentle, Andrew, October 28, 1820, advertisement (New-York Evening Post)

- “Mr ANDREW GENTLE (at the Botanic Garden) has for sale there, and at his Store, No. 155 Water-st. New-York, a general assortment of Garden and Agricultural seeds, the growth of the present year. Fruit trees (true of their kinds.) Ornamental shrubs, plants, &c. Fine hyacinths, fit for glasses; Tulips, and other bulbous roots, for the open ground; the present time is the best for planting them. Seeds put up for foreign orders with the greatest care. . . . Green-house plants received for the winter, at very moderate charge, and will have the same attention as his own. Flower-pots and garden tools.”

- Gentle, Andrew, 1841, Every Man His Own Gardener (1841: iii–vii, 34, 68, 73, 76, 80, 82–83, 89–91, 93)[21] back up to History

- “I deem it necessary . . . to acquaint the reader of the following Plain Treatise on Horticulture, with my qualifications for making considerable alterations in the mode of Gardening. . . .

- “I was brought up to horticultural work, in all its departments, and was entrusted with the management of two very extensive establishments in the Old Country for six years, before I embarked for this 'land of the free.' In the year 1805, I commenced operations for Dr. Hosack, in New-York, by laying out his grounds. On making inquiries of those who followed the business, relative to the usual time of putting some crops in the ground, the information I obtained, was, for a time, my guide. I was, however, firmly satisfied, that the ‘appointed times,’ observed by my fellow-labourers, were based on uncertainty, and of course induced repeated failure and great disappointment. . . . I perused several eminent authors on Gardening, and became thoroughly convinced that a most material deviation from their instructions must be adopted by the practical cultivator in this country, in order to crown his labours with success.

- “Upwards of twenty years ago, I was strenuously advised to publish a work on useful Gardening. My answer was that I should be laughed at—not having had an opportunity of fully testing the effect of climate on vegetable life. I have since visited the Southern States, which, together with a long residence in the State of New-York, enable me, I presume, to form pretty correct data for the profitable pursuit of Kitchen Gardening, having kept general memorandums for the whole of the above-mentioned period. . . . [back up to History]

- “It is more owing to the unskillfulness of the gardener, than to the “husbanding” of the seed seller, that so many crops fail.

- “If the directions which I have given, with respect to sowing of seeds, and the time they will grow, are followed with tolerable exactness, they will be found applicable to the various States of the Union. . . . Seeds preserved here may be safely kept much longer than those imported from Europe. . . .

- “That the study of Horticulture, too much neglected hitherto, may confer all the advantages which it is capable of bestowing; that it may make the waste places fruitful, and the wilderness to blossom as a rose, is the height of the Author’s ambition, as well as his most devout prayer.

- “CHIVES. Allium schoenoprasum. . . .

- “Plant the roots for edging to a walk or border, two inches deep, and the same distance apart, in the form you wish them to be.

- “SORREL FRENCH. Rumex acetosa. . . .

- “You may have it in a bed any size, the rows being a foot apart, or for edging along the side of a walk. . . .

- “HYSSOP. Hyssopus officinalis. . . .

- “When it comes up, set it out in any form you wish; the usual way is to make an edging for the inner side of a border. Set the plants a few inches part; if for a bed, a foot in the rows.

- “THYME. Thumus vulgaris. . . .

- “Plant slips in rows four inches apart, for edging. It does well for a walk side, or you may make a bed the same distance, the rows a foot apart.

- “STRAWBERRY. Fragaria. . . .

- “In a small or family garden they make (81) good edging along the sides of squares; in a kitchen garden plant in rows, two plants nearly together, about eighteen inches apart. . . .

- “APPLE. Pyrus malus. . . .

- “For a small garden they should be set out one foot by three in the rows. . . . They will, in three or four years, be large enough to set out for orchard purposes. . . .In setting out for an orchard, from thirty to thirty-six feet is a good distance.

- “On the Construction of a Green-House and its Size.

- “It can be heated with one fire-place, if it is forty feet long, sixteen wide, and the same in height; windows upright, and to commence two feet from the bottom, and go within three feet of the top; all hanging with weights to give air when wanted; there should be two or three in each end of the house also.

- “The principal thing is the fire place; that is to be in the rear, and to come into the house from the north-west corner is rather the best; the size in the inside to be two feet in the clear in the length, eighteen inches wide, the grate to be one foot wide, and fifteen inches long; the bars to be one inch and a half thick by one inch broad, and to lay not more than one-quarter of an inch apart, the ends to fit close together, and half in, to lay on a bar of iron, with a fall of nine inches for the ashes; the door frame for two doors, the lower one to have two holes, with valves to shut or not as may be; the bottom of the entrance into the flue to be eighteen inches above the fire-place; an arch turned over rather higher behind than before; the flues all round to be four bricks on edge, a foot wide outside, and tiles a foot wide to cover over the top, an inch and a quarter thick; all soft brick, and laid in clay mortar; it will look better and throw more heat at less expence of fire, to have the bricks laid pigeon-hole fashion. The green-house to face the mid-day sun, or a little earlier. A conservatory may range south and north with glass roof, sides and ends, within two feet of the ground, and heated in the same way. The glass for the slope of the roof had better be about six inches wide, as it is bought cheaper, and not so liable to break. The slope may be what you please, only keep as near the directions as possible for the fire-place. Either of the above directed houses should be near the house, for convenience, or amusement for the winter. The stage in the green-house may be put up any form wished, provided it has a regular slope, as the plants always look best. The flues round the house with a shelf on it, will hold a great many plants, and they will be partly out of sight. Steam pipes will hold nothing, being round, and they cost more money, and when they get out of order, you have to get an engineer to put all right again, and if that should happen in the middle of winter, the consequences may be feared. . . .

- “Grape vines can be trained up the inside of a conservatory to advantage, by making the ground good where they are planted, and having an aperture through the lower part where they grow. You may indulge your taste to a considerable extent in laying out the ground adjacent to the house, if you wish; it will have a pretty effect for various flowers, shrubs, &c.

- “It is customary to cause steam in the house in the evening, when the fire is kept up in cold weather, by occasionally pouring water along on the flue; it will make the plants have a fine appearance in the morning.

- “On the Choice of a Situation for a Garden.

- “I would prefer a kitchen garden near the house, but not fully in sight, partly surrounded with trees, ornamental as well as fruit, or grape vines, sloping a little to the south, and facing the sun at 11 o’clock, with a variety of soils, all of good depth, and free from stones or gravel, or rain water standing on it. It may be either square or oblong, but is most convenient to work when the sides are straight, with a fence of moderate height. In laying out, I would prefer a border all round the width of the fence, the walk half the width of the border, the main cross walks four feet wide, to plant currants, gooseberry, and raspberry bushes, four feet apart, or strawberry plants near the farmyard, and convenient for water.

- “For a market garden the same sort of ground, with a good fence all round. . . .”

Images

John Trumbull, Dr. Hosack’s Green houses, Elgin Botanic Garden, June 1806.

Anonymous, Elgin Botanic Garden, c. 1810.

William Satchwell Leney after Louis Simond, View of the botanic garden at Elgin in the vicinity of the City of New York, c. 1810.

William Satchwell Leney after Hugh Reinagle, “View of the Botanic Garden of the State of New York,” in David Hosack, Hortus Elginensis (1811), frontispiece.

Hugh Reinagle, Elgin Garden on Fifth Avenue, c. 1812.

Notes

- ↑ Andrew Gentle, Every Man His Own Gardener; Or, a Plain Treatise on the Cultivation of Every Requisite Vegetable in the Kitchen Garden, Alphabetically Arranged. With Directions for the Green & Hothouse, Vineyard, Nursery, &c. Being the Result of Thirty-Five Years’ Practical Experience in This Climate. Intended Principally for the Inexperienced Horticulturist (New York: The author, 1841), iii, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Gentle indicated his familiarity with Scottish weather and its effect on plants in Every Man His Own Gardener (1841, 79, view on Zotero). Thomas Gentle, “nursery and seedsman,” died at Peebles on August 22, 1824 (“Deaths,” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 16 [1824]: 488, view on Zotero). Alexander Gentle, a 50-year-old gardener in Peebles, is recorded in the Scotland census of 1841, and ten years later, as “formerly Master Nurseryman,” but now a pauper and widower lodging in Peebles. The 1851 census also records Thomas Gentle (1791–1857), nursery and seedsman of Peebles, as one of two partners in the business, with three of his children working as “nursery foreman,” “shopwoman (seedsman’s),” and “nurseryman’s apprentice.” Thos. Gentle & Son appear in the list of “Provincial Nurserymen, Florists, &c.” in The National Garden Almanack, Florists’ Diary, and Horticultural Trade Directory, for 1853 (London: Chapman & Hall, 1853), 122 view on Zotero); and Thomas Gentle & Son were still operating in 1867 as one of six nursery and seedsmen in Peebles; see Iain C. Lawson, and Joe L. Brown, History of Peebles, 1850–1990, (Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing Company, 1990; electronic repr., 2010), 34, view on Zotero; Alexander Williamson, Glimpses of Peebles; or Forgotten Chapters in Its History (Selkirk: George Lewis, 1895), 304, view on Zotero. “Mr. Gentle, Seedsman” is listed in the Ordnance Survey Name Books for Peebleshire, in 1856–58 (Peeblesshire Ordnance Survey Name Books, 1856–1858, Peeblesshire, vol. 34, pages 37, 38, 42. Scotland’s Places, Accessed September 30, 2015). See also 1841 Census, Parish of Peebles, Peeblesshire, Enumeration Book 3, Page 3; Index, Maxwell Ancestry (accessed September 8, 2015); 1851 Census, Parish of Peebles, Peeblesshire, Enumeration Book 1, Page 28, Schedule 127, and Enumeration Book 2, Page 3, Schedule 11; Index, Maxwell Ancestry (accessed August 21, 2015) and (accessed August 10, 2015); Original Source: 1841 Scotland Census, National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

- ↑ Gentle 1841, iii–iv, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, A Catalogue of Plants Contained in the Botanic Garden at Elgin: In the Vicinity of New York, Established in 1801 (New York: T. & J. Swords, 1806), 4, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, A Statement of Facts Relative to the Establishment and Progress of the Elgin Botanic Garden: And the Subsequent Disposal of the Same to the State of New-York (New York: C. S. Van Winkle, 1811), 10–11, view on Zotero.

- ↑ In June 1811, several months after arriving at the garden, Michael Dennison began a five-year lease of the property; see Addison Brown, The Elgin Botanic Garden, Its Later History and Relation to Columbia College (Lancaster, PA: The New Era Printing Company, 1908), 10, view on Zotero.

- ↑ The other two seedsmen were John Montgomery, Samuel Grundy, and Grant Thorburn. See Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, and City Directory (New York: David Longworth, 1813), 119, view on Zotero; “Early New York Seedsmen and Nurserymen,” Journal of the New York Botanical Garden 43 (November 1942): 263, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Brown 1908, 15–16, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, “Report on Botany and Vegetable Physiology,” American Monthly Magazine and Critical Review 1 (May 1817): 47, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Brown 1908, 15, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gentle 1841, 58–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For several years, Gentle occupied various addresses in the immediate vicinity of the Fly Market. His address is recorded as 103 Maiden Lane in 1813 and April 1815, and as 124 Fly Market in September 1815. He was probably displaced by a fire that broke out on July 11, 1816, nearly completely destroying the house he then occupied on the west side of the Fly Market between Pearl and Water Streets. He is recorded at 155 Water Street from 1820 until 1822. See Longworth’s American Almanac 1813, 119, view on Zotero; Advertisements in the New-York Evening Post (April 18, 1815: 3, April 19, 1815: 3, and September 14, 1815: 3); “Accidents, Crimes, &c.,” Daily National Intelligencer (July 17, 1816): 2; Longworth’s American Almanac, New York Register, and City Directory (New York: Thomas Longworth, 1822), 204, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Brown 1908, 15–16, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Longworth’s American Almanac, New York Register, and City Directory (New York: Thomas Longworth, 1823), 190, view on Zotero.

- ↑ He was paid at a rate of $1.50 per day. See Diary of Adriance Van Brunt, April 14 and 21, 1829. Louis P. Tremante III, “Agriculture and Farm Life in the New York City Region, 1820–1870” (PhD diss., Iowa State University, 2000), 317n4, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gentle may have owed his election to the New York Horticultural Society to the agency of David Hosack, the organization’s founder and first president. His misidentification of the group as the “Horticulturist Society” on the title page of Every Man His Own Gardener may betray lack of familiarity with the organization.

- ↑ Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498–1909, 6 vols. (New York: Robert H. Dodd, 1926), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hosack 1811, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, Hortus Elginensis, or, A Catalogue of Plants, Indigenous and Exotic, Cultivated in the Elgin Botanic Garden, in the Vicinity of the City of New-York: Established in 1801, 2nd ed. (New-York : Printed by T. & J. Swords, 1811), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hosack 1817, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gentle 1841, view on Zotero.