Peter Collinson

Peter Collinson (January 28, 1694–August 11, 1768), an English Quaker merchant, traded seeds and plants with colleagues across the Atlantic Ocean, especially John Bartram of Philadelphia, and is credited with introducing at least 150 species, mostly from British North America, to English gardens during the 18th century.

History

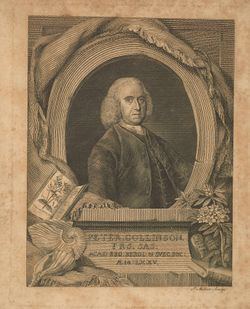

Peter Collinson was a passionate amateur gardener and significant importer of American exotics into England throughout the middle of the 18th century [Fig. 1]. Although he never traveled to North America, he maintained an active correspondence with American colonists, especially John Bartram of Philadelphia, and traded seeds and plants with associates across the Atlantic Ocean for more than three decades.[1] In addition, Collinson played an important role in supporting the nascent Library Company of Philadelphia and bolstering the scientific experiments of Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790).

Collinson was born to Peter Collinson, a Quaker cloth merchant from London, and his wife, Elizabeth Hall, in 1694. He received his “first Likeing to Gardens & plants” at his grandmother’s in Peckham, Surrey, and noted in a memorandum he wrote later in life her preference for formal topiary, such as “Clip’d Yews in shapes of Birds, Dogs, Men & Ships &c.”[2] Collinson’s “inherent curiosity” in natural history was, according to Jean O’Neill and Elizabeth P. McLean, also fostered by Quaker beliefs that encouraged gardening as a way to connect with God.[3] As a Quaker, Collinson was not permitted to attend an English university, and his knowledge of botany and natural history was likely largely self-taught, using the collection of natural history books he had amassed for his personal library.[4] In 1711 Collinson began working for his father, selling high-quality fabrics in England and the British colonies, and, about a decade later, he and his brother James took over the family import and export business.[5] Collinson gained a reputation as an able and dedicated naturalist, and, in 1728, under the sponsorship of Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), he was elected to the Royal Society.[6]

Through the Royal Society as well as his professional involvement with transatlantic trade, Collinson developed an extensive network of contacts in British North America and particularly among the Quaker community of Philadelphia. Collinson knew Thomas Penn (1702–1775), the son of Pennsylvania’s founder William Penn (1645–1718), who moved to Pennsylvania in 1732 and resided at Springettsbury, his seat on the Schuylkill River. During the nine years that Penn lived there, Collinson acted as his agent in London and provided Penn with plants he imported for his estate, including grapevines, horse chestnuts, cornelian cherries, Syringos, pyracantha, phillyrea, and long-blowing honeysuckle. Collinson also sent Penn prints of English country seats, books, and packages of seeds.[7] Collinson corresponded with prominent Philadelphians Joseph Breintnall (d. 1746), the first Secretary of the Library Company of Philadelphia, and the physician Dr. Samuel Chew (1693–1744).[8] By 1732 Collinson was helping the Library Company build its collection (view text). Through the Library Company, Collinson became acquainted with Benjamin Franklin, and, in 1745, Collinson sent Franklin publications on electricity to aid in his research. In 1751 Collinson published Franklin’s Experiments and Observations on Electricity.[9]

Collinson’s greatest interest was plants, and he developed gardens first at his home in Peckham and later at Mill Hill, located about ten miles northwest of London. In 1721 he wrote to George Robins (1697–1742) of Maryland, “Forget not Mee & My Garden,” hoping, perhaps, that Robins would send plants from North America (view text). Two years later, he received seeds and plants from his cousin, Richard Hall, of Maryland, who sent Collinson Senna marilandica and a tulip tree, among other specimens.[10] Upon visiting Collinson’s garden in Peckham, Pehr Kalm (1716–1779), a Swedish botanist and student of Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), described how Collinson used horses’ knucklebones to edge the borders and remarked that it was “a beautiful little garden, full of all kinds of the rarest plants, especially American ones” (view text).

Collinson’s garden became even more ambitious in 1749, when Collinson and his family moved from their home in Peckham to Ridgeway House in Mill Hill. Although his wife inherited the house upon the death of her father, Collinson had begun cultivating plants at the garden at Mill Hill years earlier.[11] His garden was better known for the variety of specimens he collected than for its overall design. While botanic artists such as Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708–1770), George Edwards (1694–1773), and Mark Catesby (1683–1749) illustrated individual plants from Collinson’s garden, there is no known depiction of the garden itself.[12] Collinson’s collection of lilies and orchids was particularly noteworthy.[13] He raised exotics in a forty-two-foot-long greenhouse and wrote about his delight at being able to “smell the sweets of so many odoriferous plants,” even when his garden was snow-covered (view text).[14] His collection was targeted by thieves, and Collinson lamented in 1762 that “twenty-two different species of my most rare & beautifull plants” had been stolen from his garden (view text).[15]

Collinson made his greatest impact on botanical and horticultural history, however, as an importer of plants from North America. Although Collinson claimed to make no profit from these activities, he was, according to Alan W. Armstrong, “a demanding collector who badgered his ship-captain friends and commercial contacts (especially in Quaker Philadelphia) for specimens and good local collectors.”[16] The Philadelphia botanist and horticulturalist John Bartram (1699–1777) was Collinson’s most important and prolific supplier of North American plants, and the two men exchanged plants and seeds for more than three decades. This network of exchange helped supply the period fashion for American plants in English gardens.[17] Mark Laird has argued that “Through regular consignments of more than one hundred woody species, Bartram and Collinson effectively afforested English shires with Pennsylvanian wilderness.”[18]

They never met in person, but their letters evidence a strong friendship grounded in a “shared love of gardening and a fanatical desire for new plants.”[19] Collinson began corresponding with Bartram in 1733, and the following year Bartram sent Collinson his first shipment of plants from North America. By January 1735 he had begun to pay Bartram for this kind of work.[20] Collinson wrote that he “employed Him [Bartram] to Collect Seeds, 100 species in a box at five guineas Each from the year 1735 to this year 1760 about 20 boxes a Year.”[21] Collinson served as the middleman, selling the plants that he obtained from Bartram to various botanists, gardeners, and nurserymen throughout England and Europe; he also kept some specimens, including mountain magnolia (Magnolia acuminata), “sarsifrax” [sassafras], rhododendrons, kalmias, and azaleas, for his own garden at Mill Hill.[22]

Their most significant—and first—patron was Robert James (1713–1742), the eighth Baron Petre, of Thorndon Hall in Essex. Collinson arranged for Bartram to send Lord Petre two boxes of North American tree seeds—including several species of hickory, white and black walnut trees, sassafras, dogwood, red cedar, sweet gum, swamp laurel (magnolia), spruce (hemlock), chestnut oak, white oak, swamp Spanish oak, and tulip tree—in the fall of 1735.[23] Several years later, Collinson wrote to Bartram of Lord Petre’s gardens that “when I walk amongst them, One cannot well help thinking He is in North American thickets—there are such Quantities” (view text). Lord Petre also desired live animals from North America for his estate, and Bartram sent terrapins and turtles to stock the ponds at Thorndon Hall.[24] According to Collinson’s records, Bartram also sent boxes to Edward Howard (1686–1777), the ninth Duke of Norfolk (and Lord Petre’s cousin), at Worksop Manor; Charles Lennox (1701–1750), the second Duke of Richmond, at Goodwood; John Russell (1710–1771), the fourth Duke of Bedford, at Woburn; Archibald Campbell (1682–1761), the third Duke of Argyll, at Whitton; John Stuart (1713–1792), the third Earl of Bute; Norborne Berkeley (d. 1770), Lord Botetourt at Stoke Park; and Charles Hamilton (1704–1786) at Painshill Park, among many other patrons.[25]

Scholars have argued that the collaboration between Collinson and Bartram bolstered both men’s reputations. Bartram probably would not have secured the financial support needed to undertake the collecting expeditions that made him “the preeminent American naturalist of his time.”[26] Collinson also provided Bartram with exotics that he could not easily obtain otherwise (view text).[27] Collinson is credited with introducing at least 150 new species from British North America to Europe—many of which were provided by Bartram.[28] Without Bartram’s plants, Collinson likely would have been remembered as “a minor figure in the history of the Royal Society,” according to Armstrong.[29] Indeed, it was one of Bartram’s plants that ensured Collinson’s legacy: it was only after Linnaeus named a species native to eastern North America after Collinson in 1737—a specimen of which Collinson sent to Linnaeus for study—that the naturalist felt his contributions to the field had been adequately honored. He thanked the Swedish botanist for naming the plant Collinsonia canadensis and thus “giving Mee a species of Eternity (Botanically speaking) . . . a name as long as Men and Books Endure” () [Fig. 2].[30]

—Lacey Baradel

Texts

- Collinson, Peter, October 6, 1721, in a letter to George Robins of Talbot County, MD (quoted in O’Neill and McLean 2008: 12)[31] back up to History

- “I can't forget our former familiarity aboard Ship & tho it too often happens that absence & Difference breed a Bane to frdship Yett those circumstances will never be able to Produce such an effect in Mee . . . Dear George. I wish thee Health and Prosperity & I will raise my Wishes Higher, a Happy Eternity. Forget not Mee & My Garden.”

- Collinson, Peter, c. 1730, in a letter to William Byrd II (Tinling, ed., 1977: 1:423)[32]

- “A good situation is a very essential point to be considered in the choice of a vineyard a gentle declivity to the south is esteemed the best, which more speedily carries off the water, which on a flat is apt to stay long, & is very prejudicial, a sandy gravelly dry soil is best. Juices produced from this, is stronger & better flavoured, than from a low moist situation.

- “A good shelter is very necessary & should be raised on all sides but the south by raising plantations of trees of the quickest growth as hickory locust, &c. but on that side which is most exposed to the strongest winds the plantation must be made more formidable but let none be planted so near the vines as to drip upon them.”

- Collinson, Peter, July 22, 1732, in a letter to the Library Company of Philadelphia (2002: 9)[33] back up to History

- “I am a Stranger to most of you but not to your laudable Designe to erect a publick Library. I beg your acceptance of my Mite: Sr Isaac Newtowns Philosophy & Philip Millers Gardening Dictionary. It will be an Instance of great Candour too accept the Intention & Good Will of the Giver and not regard the meaness of the Gift."

- Collinson, Peter, after 1733, in his Commonplace Book (quoted in O’Neill and McLean 2008: 103)[31]

- “My Connection with our Colonies in the Course of Trade, & my Love for planting & Improvements putt mee Early on the Scheme of procuring Seeds, as well for my own planting as Others—but it was many years before I could do anything to any Purpose untill luckily, anno 1733 I was recommended to Bartram.”

- Collinson, Peter, January 24, 1734, in a letter to John Bartram (quoted in Armstrong 2004: 31)[34]

- "I wish att a proper season Thee would procure a strong box 2 feet square and about 15 or 18 inches deep but a foot Deep in Mould will be enough. Then collect half a dozen Laurels and half a Dozen shrub Honeysuckles [azaleas] and plant in this Box, but be sure to make the bottome of the Box full of large Holes and cover the Holes with Tiles or oyster shells to Lett the Water draine better off. Then Lett this box stand in a proper place in thy Garden for two or three years till the plants have taken good Root and made Good Shoots. But thee must be Care full to water it in Dry Weather."

- Collinson, Peter, January 20, 1735/36, in a letter to John Bartram (quoted in Armstrong 2004: 31)[34]

- “ . . . takeing the following Methode I have raised a great many pretty plants out of your Earth. I lay out a Bed 5 or 6 feet long, 3 foot Wide. Then I pare off the Earth and Inch or Two Deep, then I Loosen the bottome and Lay it very smooth again and thereon (if I may use the Term) I sow the Sand & Seed together as thin as I can. Then I sift some good Earth over it about half an Inch thick. This bed ought to be In Some place that It may not be Disturbed & kept very Clear from Weeds for several seeds come up not til the second year."

- Collinson, Peter, January 24, 1735, in a letter to John Bartram (quoted in Weisberg-Roberts 2011: 160)[35]

- “I am very sensible of the great pains and many tiresome steps to collect so many rare plants scattered at a distance. I shall not forget it; but in some measure to show my gratitude, though not in proportion of they trouble I have sent thee a small token: a calico gown for thy wife.”

- Collinson, Peter, February 12, 1735/36, in a letter to John Bartram (quoted in Armstrong 2004: 33)[34] back up to History

- “I have got a Box of Chestnuts in sand & some Spanish nutts & some of our Kathrine peach stones. It is the last & a large peach that ripens with us in October. But will sooner with you. It is a hard sound well flavoured peach none better & Clings to the stone, 17 & as many apricot stones & in the Little Box that the Insects came in are some seeds. The China Aster is the Noblest & finest plant thee Ever saw of that Tribe. It was sent per the Jesuits from China to France & thence to us. It is an Annual. Sow it in a rich mould immediately & when it has half a Dozen Leaves transplant to the Borders. It make a glorious autumn flower. There is White and purple in the Seeds.”

- Collinson, Peter, May 13, 1739, in a letter to Carl Linnaeus (2002: 72)[33] back up to History

- “I am glad of this conveyance to Express my Gratitude for the perticular regard shown for me in that Curious Elaborate Work the Horts Clifforts. Some thing I think was Due to Mee from the Common Wealth of Botany for the great number of plants & Seeds I have annually procur’d from Abroad, and you have been so good as to pay It, by giving Mee a species of Eternity (Botanically speaking), That is, a name as long as Men and Books Endure. This layes Mee under Great Obligations, which I shall never Forgett.

- “I am concerned I can make no better acknowledgments then by the Small token of Pensilvania Ores [not identified], which the Bearer will Deliver to you.”

- Collinson, Peter, September 1, 1741, describing the gardens of Lord Petre at Thorndon Hall in Essex, England, in a letter to John Bartram (quoted in Laird 1999: 64)[36] back up to History

- “ . . . the Trees & shrubbs raised from thy first seeds is grown to great maturity[.] Last year Ld petre planted out about Tenn thousand Americans wch being att the Same Time mixed with about Twenty Thousand Europeans, & some Asians make a very beautifull appearance great Art & skill being shown in consulting Every one’s pticular growth & the well blending the Variety of Greens[.] Dark green being a great Foil to Lighter ones & Blewish green to yellow ones & those Trees that have their Bark & back of their Leaves of white or Silver make a Beautifull Contrast with the others

- “the whole is planted in thickets & Clumps and with these Mixtures are perfectly picturesque and have a Delightfull Effect—this will just give thee a faint Idea of the Method Lord Petre plants In which has not been so happly Executed by any and Indeed they want the Materials whilst his lordship has them in plenty[.] His nursery being fully stocked with Flowering shrubs of all Sorts that can be procured, with these He borders the out skirts of all his plantations and He continues Annually Raising from Seed and Laying, budding, grafting that 20 Thousand Trees are hardly to be missed out of his Nurseries. . . .

- “when I walk amongst them, One cannot well help thinking He is in North American thickets—there are such Quantities.”

- Collinson, Peter, March 30, 1745, in a letter to Cadwallader Colden (quoted in Volmer 2008: 46)[37]

- “I commend your prudence in Directing your Seeds for the Paris Garden. The professors are Messrs Jussieu. Without that precaution a hundred to one but that they had been thrown into the Sea. But if you had Improved that precaution & Divided the Seeds into Two parcells & Sent by Two ships, then in all probability I should have had the Delight of shareing in the pains that you had taken to oblige Your Friends. Whilst these perilous Times Last I recommend it to you for the future.”

- Kalm, Pehr, September 1748, describing Peter Collinson’s garden at Peckham (quoted in Brett-James 1926: 30–31)[38] back up to History

- “June 10, in the afternoon, I went to Peckham, a pretty village which lies 3 miles from London in Surrey, where Mr. Peter Collinson has a beautiful little garden, full of all kinds of the rarest plants, especially American ones, which can endure the English climate and stand out the whole winter. However neat and small it is there is scarcely a garden where so many kinds of trees and plants, especially the rarest, are to be found. Peter Collinson uses knucklebones for his borders and he explained to me his method of sowing mistletoe and also experiments he had made with cranberries. He thinks it is best for a garden to have the morning sun so that it may help to dry up the vapours. Quadrilateral is the best shape and is the one which he has adopted, whereas the gardens of the Duke of Richmond are round. The sun is not so effective. He told me also of the use of meadowland in Middlesex, north of Hamptstead. The people do not use the plough but keep horses and hardly any cattle. The manure thus obtained is sent to London frequently. I saw a tree clipped to form the roof of a summer-house and also a chestnut cut so as to make a shelter over a bench.”

- Collinson, Peter, January 20, 1751, in a letter to John Bartram (quoted in Laird 1999: 72)[36]

- “I am very much Obliged to my good Friend J. Bartram for so fine a Collection of growing plants—if they had all come to my Hand I should have troubled Thee no further but to my great Loss some prying knowing people Looked into the Cases and out of that No. 2: took the 3 Roots of Chamaerhododendrons, Red Honeysuckle[,] Laurel[,] Root of Silver Leafed Arum & the Spirea alni folio[.] these was the Most Valuable part & what I most Wanted, it is very vexatious wether taken out on board or Coming up from the Ship I can’t Say—but this is Certain they was gone—I wish Ld: Northumberland had not the Same bad luck for as I peeped In I could see but very Little—but as I have had no complaints I hope it was otherwise. . . . I fancy some of the sailors having relatives gardeners seeing these plants so carefully boxed up took them for rarities so were tempted to steal them to give to their friends.”

- Collinson, Peter, October 5, 1757, in a letter to Cadwallader Colden (1923: 5:190)[39]

- “I have in Mrs Alexanders Trunk Sent you the Herbals you wanted and putt in 2 or 3 of Erhetts Plants, for your Ingenious Daughter to take Sketches of the fine Turn of the Leaves &c. & Lin: Genera.

- “I wish your fair Daug[hte]r was Near Wm Bartram he would much assist her at first Setting out. John[’s] Son a very Ingenious Ladd who without any Instructor has not only attained to the Drawing of Plants & Birds, but He paints them in their Natural Colours So Elegantly So Masterly that the best Judges Here think they come the Nearest to Mr Ehrets, of any they have Seen[.] it is a fine amusement for her[;] the More She practices the more She Will Improve, by another Ship, I will Send Some more prints but as they are Liable to be taken I Send a few at a Time.”

- Collinson, Peter, 1760?, inscribed on the back of a letter from C. Polhill to Peter Collinson dated March 17, 1760 (quoted in Armstrong 2004: 24)[34]

- “I have for many years past to Improve or at Least embellish my Country at the request of many of the Nobility & Gentry—with no little Trouble & Some expense—procured annually Boxes of Pensilvania Seeds Having only my Labour for my Pains without the Least profit or advantage. . . .

- “My Connection with our Colonies in the Course of Trade & my Love for planting & Improvement—putt mee Early on the Scheme of procuring Seeds as well for my own planting as others—but it was many years before I could do any Thing to any purpose until Luckily anno 1733 I was recommended to Bartram (in anno 1736 Seed sent of Pennsylvania) a Native of that Country who I Shall Direct to putt you up a Box of Seeds for next year.”

- Collinson, Peter, June 11, 1762, in a letter to John Bartram (quoted in Laird 1999: 72)[36] back down to note

- “I forgot in my Last to tell thee my Discidious Mountain Magnolia I have raised from Seed about 20 years agon flowers for the First Time with Mee & I presume is the first of that species that ever flowerd in England & the Largest & Tallest, the Flowers come Early Soone after the Leaves are formed—The Great Laurel Magnolia & umbrella both fine trees in my Garden showed their flower Budds the first of June—my Red flowering Acacia is now in full flower and makes a glorious show as well as the White but above all is the Great Mountain Laurel or Rhododendron in all its Glory—this 10th June, what a Ravishing Sight will the Mountains appear when alive with this rich embroiderie[.] How Glorious are thy Works o Lord, they inspire Mee with Admiration & Praise.”

- Collinson, Peter, October 5, 1762, in a letter to John Bartram (quoted in Laird 1999: 72)[36] back up to History

- “Plants languishing and perishing for want of rains & many totally killed but my greatest loss has been from a villain who came & robbed Mee of twenty-two different species of my most rare & beautifull plants[.] took all my fine tall marsh Martagons that thee sent me last year which was different in colour from any I have had before[.] all my fine yellow Lady’s Slippers that I have had so long & flowered so finely every year. These I regret most for they are not to be had again, but by thy Assistance & though I Doubt not of thy inclination, yett, as I apprehend they are found accidentally so it may not be in thy power to assist Mee.”

- Collinson, Peter, February 25, 1764, in a letter to Cadwallader Colden (quoted in Volmer 2008: 68)[37]

- “As often as I survey my Garden & Plantations it reminds Mee of my Absent Friends by their Living Donations. See there my Honorable Friend Governor Colden how thrifty they look. Sir, I see nobody but Two fine Trees, a Spruce & a Larch, that’s True, but they are his representatives. But see close by how my Lord Northumberland aspires to that Curious Firr from Mount Ida but Look Yonder at the Late Benevolent Duke of Richmond, His Everlasting Cedars of Lebanon will Endure when you & I & He is forgot.”

- Collinson, Peter, February 29, 1768, in a letter to John Bartram (quoted in O’Neill and McLean 2008: 50)[31] back up to History

- “. . . whilst snow covered the Garden without . . . out of my parlour I go into my Greenhouse 42 foot long which makes a pretty walk to smell the sweets of so many oderiferous plants, Winter without but Summer within.”

Images

Other Resources

Library of Congress Authority File

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Mill Hill Preservation Society

Notes

- ↑ Alan W. Armstrong writes, “Although Collinson traveled extensively around England, he left it only once and never visited America”; see introduction to Peter Collinson, “Forget Not Mee & My Garden”: Selected Letters 1725–1768 of Peter Collinson, F.R.S., ed. Alan W. Armstrong (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2002), xxv, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Quoted in Jean O’Neill and Elizabeth P. McLean, Peter Collinson and the Eighteenth-Century Natural History Exchange, Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2008), cclxiv, 6, view on Zotero.

- ↑ O’Neill and McLean 2008, 5, view on Zotero.

- ↑ According to Armstrong, Collinson’s library included “most of the natural histories available and published in his time, along with biographies, travel accounts, gazetteers, geographies, mythologies, books on antiquities, astronomy, and practical science”; Armstrong 2002, xxiii, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Armstrong 2002, xxxv, view on Zotero.

- ↑ O’Neill and McLean note that Collinson sponsored seventy-seven candidates for election to the Royal Society, including Mark Catesby, Georg Ehret, Benjamin Franklin, and Carl Linnaeus; O’Neill and McLean 2008, 26–27, view on Zotero. Collinson was also elected a member of the Society of Antiquaries in 1737 and of the Royal Society of Sweden in 1747. Armstrong 2002, xxxv, view on Zotero.

- ↑ O’Neill and McLean 2008, 93–94, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alan W. Armstrong, “John Bartram and Peter Collinson: A Correspondence of Science and Friendship,” in America’s Curious Botanist: A Tercentennial Reappraisal of John Bartram, 1699–1777, ed. Nancy E. Hoffmann and John C. Van Horne (Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 2004), 28, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Armstrong 2004, 28, view on Zotero; Alfred E. Schuyler, chronology in O’Neill and McLean 2008, xx-xxi, view on Zotero. Collinson and Franklin finally met in person in London in 1757; Schuyler 2008, xxi, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Armstrong 2002, xxxv, view on Zotero; Schuyler 2008, xix, view on Zotero; O’Neill and McLean 2008, 80, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Collinson married Mary Russell (1704–1753) in 1724. Together they had a son named Michael (1727–1795) and a daughter named Mary. Before the family moved to Mill Hill, Collinson spent two years transferring plants from his garden in Peckham to Ridgeway House. Armstrong 2002, xxv, xxxv, view on Zotero; Stephanie Volmer, “Planting a New World: Letters and Languages of Transatlantic Botanical Exchange, 1733–1777” (PhD diss., Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 2008), 48, view on Zotero; O’Neill and McLean 2008, 146, view on Zotero.

- ↑ O’Neill and McLean 2008, 1, view on Zotero; Joel T. Fry, “America’s ‘Ancient Garden’: The Bartram Botanic Garden, 1728–1850,” in Knowing Nature: Art and Science in Philadelphia, 1740–1840, ed. Amy R. W. Meyers (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 66, [1]. Armstrong observes that “while many of his contemporaries remarked on the extent and range of his collection, none describe the arrangement of the whole as remarkable”; Armstrong 2002, xxv, view on Zotero.

- ↑ O’Neill and McLean 2008, 144, view on Zotero.

- ↑ According to O’Neill and McLean, it remains unknown whether Collinson’s father-in-law left a greenhouse at Mill Hill or whether Collinson added it later. O’Neill and McLean 2008, 145, view on Zotero.

- ↑ His gardens were also robbed in 1765 and 1768. O’Neill and McLean 2008, 153, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Armstrong 2004, 28, view on Zotero; O’Neill and McLean 2008, 79, view on Zotero.

- ↑ The influx of American plants into England prompted Collinson to write in 1756 that “England must be turned up side down & America transplanted Heither.” Mark Laird has argued that by the early 19th century the fashion for American plants in England faded in favor of exotics from Asia; see his The Flowering of the Landscape Garden: English Pleasure Grounds, 1720–1800 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), 17, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Mark Laird, “This Other Eden: The American Connection in Georgian Pleasure Grounds, from Shrubbery and Menagerie to Aviary and Flower Garden,” in Knowing Nature: Art and Science in Philadelphia, 1740–1840, ed. Amy R. W. Meyers (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 96, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Breintnall and Chew first recommended Bartram to Collinson; Fry 2011, 63, [2].

- ↑ Schuyler 2008, xx, view on Zotero; Armstrong 2004, 23, 32, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Quoted in O’Neill and McLean 2008, 103, view on Zotero.

- ↑ According to Fry, Bartram also arranged special boxes for Collinson alone that included rare specimens of live plants and roots. These curiosities “quickly made Collinson’s garden famous.” In 1762, Collinson noted that the mountain Magnolia that he had raised from seed twenty years earlier had finally flowered (view text); see Fry 2011, 65–66, [3].

- ↑ Fry 2011, 64, [4]. Bartram continued to send Lord Petre boxes of seeds, via Collinson, annually until at least 1739. Laird 1999, 70, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Laird 2011, 103, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James A. Jacobs, John Bartram House and Garden, Greenhouse (Seed House), Historic American Landscapes Survey No. PA-1 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2001), 24, [5]. See also Laird 1999, 67, 69, 86, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Armstrong 2004, 25, view on Zotero; O’Neill and McLean 2008, 103, view on Zotero.

- ↑ See also Fry 2011, 68, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Rhododendron maximum and Sanguinaria canadensis are among the species that Collinson introduced to England. He is also credited with introducing the first tropical orchid to flower in England; see O’Neill and McLean 2008, 53, 79, view on Zotero. According to Volmer, Collinson may have introduced as many as 180 species; Volmer 2008, 37, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Armstrong 2004, 25, view on Zotero

- ↑ Theresa M. Kelley, Clandestine Marriage: Botany and Romantic Culture (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 24, [6]. Laird says that the specimen was introduced to England in 1734; Laird 1999, 221, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 O’Neill and McLean 2008, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Marion Tinling, ed., The Correspondence of the Three William Byrds of Westover, Virginia, 1684-1776, 2 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1977), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Peter Collinson, “Forget Not Mee & My Garden”: Selected Letters 1725–1768 of Peter Collinson, F.R.S., ed. Alan W. Armstrong (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2002), ccxli, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Armstrong 2004, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alicia Weisberg-Roberts, “Surprising Oddness and Beauty: Textile Design and Natural History between London and Philadelphia in the Eighteenth Century,” in Knowing Nature: Art and Science in Philadelphia, 1740-1840, ed. Amy R. W. Meyers (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 Laird 1999, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Volmer 2008, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Norman G. Brett-James, The Life of Peter Collinson (London: Edgar G. Dunstan & Co., 1926), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cadwallader Colden, The Letters and Papers of Cadwallader Colden, Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1921 (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1923), vol. 5, view on Zotero.