Nursery of Robert Buist

Overview

Alternate Names: Buist’s Nursery; R. Buist’s Exotic Nursery; Robert Buist’s City Nursery & Greenhouses

Site Dates: 1833–c. 1850

Site Owner(s): Robert Buist 1805–1880;

Associated People: Mr. Scott, gardener;

Location: Philadelphia, PA · 39° 56' 39.16" N, 75° 9' 49.43" W

Condition: Demolished

Keywords: Border; Greenhouse; Hothouse; Nursery; Pot; View/Vista; Walk

The nursery of Robert Buist was a key source of exotic flowers in Philadelphia in the 1830s and 40s. Robert Buist knew many of the gardeners and seedsmen from his native Britain, from whom he often procured rare species of camellias, dahlias, geraniums, and roses to sell at his city nursery on South 12th Street in Philadelphia.[1] Local naturalists, such as the botanist Thomas Nuttall, also provided plants collected on travels to different regions of the North American continent.

History

Robert Buist first entered the nursery business in 1830 as partner to Thomas Hibbert, whose garden and greenhouses were located at South 13th Street in Philadelphia.[2] Hibbert was likely eager to join with Buist, a Scottish émigré, due to his familiarity with nurserymen in Scotland and England—one of Buist’s first tasks after partnering with Hibbert was to travel to Britain to import exotics not available in the United States.[3] According to an 1832 notice in the Gardener’s Magazine, he brought back to Philadelphia “large collections of Chinese, Cape, and Botany Bay plants” to sell at Hibbert & Buist.[4] Unfortunately, their collaboration was brief due to Hibbert’s sudden illness and death in May 1833.[5]

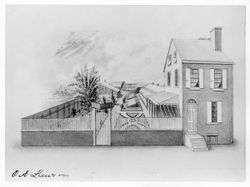

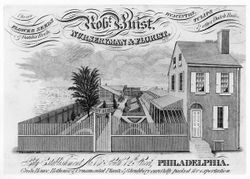

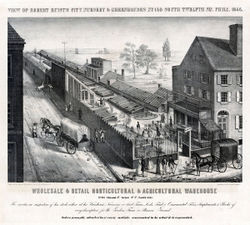

Buist quickly established a seed warehouse on Chestnut Street and an independent nursery at 140 South 12th Street, which he opened by December 1833 [Fig. 1], using part of the Hibbert & Buist stock.[6] It was often referred to as “R. Buist’s Exotic Nursery” for the rich variety of rare plants it offered, both from abroad and from the Pacific Northwest, the latter of which had been collected by Thomas Nuttall during his 1834 expedition along the Columbia River.[7] Descriptions of the nursery from 1833 and 1835 describe the layout and contents of his greenhouse, which was divided into five compartments to accommodate the different climates his exotic plants required [Fig. 2]. The front compartment was the “New-Holland House” and featured various heaths, Banksia, diosma (Coleonema pulchellum), and other plants then uncommon in the United States. A hothouse or stove occupied the second compartment, and the final three compartments were each dedicated to a specific flower: the geranium, the camellia, and the rose.[8] Buist later expanded his nursery in order to build an additional stove and an entirely separate, north-facing camellia house [Fig. 3]. He noted that camellias benefited when partially shaded, and advised patrons to white-wash the glass of their greenhouses or place them in north-facing situations to protect the flowers.[9]

Camellias were not the only plant that was subject to Buist’s careful study; roses also received his focused attention, and he is known to have introduced the Jaune Desprez—a yellow climbing rose with a strong fragrance—to the American market.[10] Indeed, in 1844 Buist published the Rose Manual, which described different types of roses and their cultivation and care. The book followed his 1832 publication of the American Flower Garden Directory that, along with the Rose Manual, were important adjuncts to his nursery business. His publishing efforts allowed him to sell his customers exotic flowers, as well as directions for their proper maintenance, adding to his professional success.

By 1848 his business had outgrown 140 South 12th Street, and Buist purchased a plot of land southwest of Philadelphia, not far from the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, to accommodate its expansion. Called Rosedale, it was considered the largest nursery in the United States at the time; a period description of the site indicated that it comprised about 100 acres of land and more than 20,000 feet of greenhouses featuring “everything in the plant way.”[11] In 1850 Buist ultimately gave up his city nursery in order to consolidate all of but his seed warehouse at Rosedale.[12] According to Joel T. Fry, the expansion of Buist’s horticultural empire may have been one of the factors that led to the bankruptcy and sale of Bartram’s Garden that year.[13]

—Elizabeth Athens

Texts

- Anonymous, May 15, 1832, describing the nursery of Robert Buist (National Gazette and Literary Register)[14]

- The Green House of Robert Buist is 150 feet long, 18 feet wide, and 15 feet high, with correspondent glass framing. It is divided into five compartments, each appropriated to plants requiring the same treatment. In the New-Holland house there are several fine specimens of Banksias, such as speciosa, grandis, cunninghamia and verticillata. There is likewise a beautiful plant of dryandra; some of the heaths are very fine; erica rubida is a great picture; diosma is also a conspicuous genus; with plants of epacris, boronia, protea, and many others of more every day observation.

- The Hot House also contains some very rare plants, such as ardisia paniculata, justicia picta, dracaena terminalis, latania borbonica, pandanus, astrapaea, myrtus pimentiodes or allspice tree; —cactus are likewise improved with the fine blooming sorts, such as Ackermania, Jenkinsonia, and Buonapartea; — Buonapartea juncea is also a curious looking plant.

- The Geranium House is well filled with fresh young and healthy plants: there are upwards of 100 varieties, some of which are very splendid; and a few years ago a single plant cost in London £2 2s sterling.

- The Camellia House begins to appear in its glory: the plants are in great luxuriance, and display a profusion of buds. It is said that sixty varieties will bloom during the winter. It would be too tedious to give a detail of their characters—but suffice to say that nivalis, eximia, rosea, reticulata, imbricata, Gray’s invincible and Floyii have a place among seventy other sorts. As for the beautiful speciosa and the pretty fimbriata, they appear to be as plentiful as the common varieties.

- The sixth [sic; fifth] is the Rose House, containing about eighty varieties and species of China rose: the yellow and white tea-scented rose is in great abundance. There are also odorata Golconda, odorata grandi and odorata superba, new sorts. Rosa smithii, or yellow noisette, is looked upon as a great treasure.

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), March 1835, “R. Buist’s Exotic Nursery, 12th, near Lombard street” (American Gardeners’ Magazine 1: 203)[15]

- The range of green-houses is upwards of one hundred feet in length; it is built with a span roof, though in some places it is not glazed, and is divided into five compartments; he intends enlarging it the present summer, and also to build a house purposely for his Caméllias, of which he has a very fine collection. . . .

- The arrangement of the plants throughout the whole range, is highly creditable to Mr. Buist’s taste; and the general good order which exists throughout his establishment, where propagation is continually going on, is to be much commended. Too little attention is paid to neatness by many nurserymen. . . .

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), March 1837, “R. Buist’s Exotic Nursery” (Magazine of Horticulture 3: 202)[16]

- Since the spring of 1835, the time of our last visit to this place, Mr. Buist has erected a camellia house and a small stove. The former is about fifty feet in length, and twenty in width, and is built with a slope to the north instead of the south, as is usual in the erection of all similar structures. . . . We noticed that Mr. Buist has the camellias placed at a good distance from the glass; this we much approve of: we know from our own personal experience that camellias, placed upon a stage near the glass, rarely make a healthy growth. . . No plants will bear growing at a greater distance from the glass than camellias.

- The interior of this house is constructed with a front shelf, about four feet in width; between this and the back border is the walk. In the border are planted out several camellias at various distances, and the space between them is filled with plants in pots. The front shelf was filled with azaleas and other plants, which prefer a cool temperature and shady situation. . .

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, June 1849, “Visit to Buist’s Nursery” (Horticulturist 4: 43–4)[17]

- While we were in Philadelphia, early last month, we had a great deal of pleasure in visiting the exotic department of Buist’s nursery establishment. Mr. Buist has for a long time, we believe, employed more capital in exotic floriculture than any other commercial grower in the country. His extensive trade, especially with the southern and western states has enabled him to introduce immediately every new species, and to maintain an immense stock of all the finest exotics in cultivation.

- Mr. Buist’s establishment consists at the present moment of three distinct departments—1st. An extensive seed warehouse, No. 99 Chestnut St.; —2d. The city Green-houses or exotic nursery, 140 South Twelfth St.; —3d. The general hardy nursery of fruit and ornamental trees, and seed farm on the Darby road. The buildings have now so completely surrounded the city establishment, that Mr. B. informed us it is his intention to remove all the exotic department next year to his general nursery and seed farm on the Darby road—thus consolidating the whole establishment as much as possible. Either the amateur or the professional horticulturist who wishes to see all the garden novelties of the day, will find a great deal to interest him in a visit to Mr. Buist.

Images

A. Hoffy, “View of Robert Buist’s City Nursery and Greenhouses,” 1846.

Notes

- ↑ U. P. Hedrick, History of American Horticulture in America to 1860 (1950; repr. Portland, OR: Timber Press, 1988), 248, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Meehan, “Robert Buist,” Gardener’s Monthly and Horticulturist 22, no. 264, ed. Thomas Meehan (December 1880): 373, view on Zotero.

- ↑ “Hibbert & Buist,” Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser (September 17, 1831): 4, view on Zotero, and William Wynne, “Some Account of the Nursery Gardens and the State of Horticulture in the Neighbourhood of Philadelphia,” Gardener’s Magazine, and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 8, no. 30, ed. J. C. Loudon (June 1832): 273, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Gordon, “Notices of Some of the Principal Nurseries and Private Gardens in the United States,” Gardener’s Magazine, and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 8, no. 30, ed. J. C. Loudon (June 1832): 283, view on Zotero.

- ↑ “Died,” Philadelphia Inquirer (May 13, 1833): 2, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Meehan 1880, 373, view on Zotero.

- ↑ C. M. (Charles Mason) Hovey, “Notes on Nurseries and Private Gardens, visited in the early part of March,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 3, no. 6, ed. C. M. Hovey (June 1837): 205, view on Zotero.

- ↑ National Gazette and Literary Register (December 19, 1833): 2, view on Zotero, and C. M. H. [C. M. (Charles Mason) Hovey], “Notices of Some of the Gardens and Nurseries in the Neighborhood of New York and Philadelphia,” American Gardeners’ Magazine, and Register of Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Horticulture and Rural Affairs 1, no. 6, ed. C. M. Hovey (June 1835): 203, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hovey 1837, 202–3, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Meehan 1880, 373, view on Zotero.

- ↑ “A Visit to Rosedale,” Florist and Horticultural Journal 4 (1854): 152–53, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Meehan 1880, 373, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Email correspondence with author, August 10, 2018. For more details on the competition between Buist and the Bartram family, see Joel T. Fry, “The Introduction of the Poinsettia at Bartram’s Garden,” Bartram Broadside (Winter 1994–95): 3–7, view on Zotero.

- ↑ National Gazette and Literary Register (May 15, 1832): 2, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hovey 1835, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hovey 1837, view on Zotero.

- ↑ “Notes made during a visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and intermediate places, from August 8th to the 23rd, 1841,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 4, no. 1, ed. Andrew Jackson Downing (July 1849): 43–4, view on Zotero.